Abstract

Among the 665 patients who registered at our hospital, we reviewed 39 cases of high grade primary osteosarcoma in patients who were older than 40 yr of age. The aim of this study was to determine if a primary osteosarcoma in older patients has different clinical features, and a poorer prognosis than in younger patients. Two evaluations were performed. In the first, an attempt was made to determine the possible prognostic factors such as gender, location, size, alkaline phosphatase, radiological findings, chemotherapy intensity, chemotherapy-induced tumor necrosis, and surgical margin. The second evaluation involved assessment of whether there were any significant clinical differences between older patients and adolescents. According to the results, a primary osteosarcoma in older patients did not reveal any significant prognostic variables. A primary osteosarcoma in older patients showed a poorer prognosis due to relatively unusual locations, common abnormal radiological findings, and a poor response to chemotherapy. Therefore, careful attention should be paid to making an accurate diagnosis and new strategies for more effective treatment, including chemotherapy, must to be developed in order to achieve long term survival in older patients with osteosarcoma.

Keywords: Aged, Prognosis, Prognostic Factor, Osteosarcoma

INTRODUCTION

An osteosarcoma is the most common childhood malignancy of the bone (1). The incidence peaks in early to middle adolescence and the tumor is relatively rare in older patients. According to previous reports (2,3), despite the development of multi-modality treatments, older patients with osteosarcoma patients have an unfavorable prognosis. Information related to the clinical outcome of older patients with osteosarcoma revealed that the dismal prognosis is due to the fact that, in older patients, osteosarcoma is likely a secondary lesion. Many studies report that most osteosarcoma in older patients results from a sarcomatous transformation of Paget's disease of the bone, or as a complication of irradiation. However, in Korea and Japan, secondary osteosarcoma in older patients is rare on account of the rarity of Paget's disease in Asians. In order to confirm the poor prognosis associated with the diagnosis of osteosarcoma in older patients, we identified 665 osteosarcoma cases treated at our hospital. Thirty-nine primary osteosarcoma cases involving patients older than 40 yr of age and forty-three adolescent patients were included.

The aim was to determine if a primary osteosarcoma in patients older than 40 yr of age have different clinical features and a poorer prognosis than adolescent patients. In addition, assessment of the main cause for the poor survival and a possible solution were investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Review of 665 high-grade osteosarcoma patients who underwent treatment in our hospital, between May 1985 and September 2002 was undertaken. Two pathologists reviewed the microscopic slides of biopsied specimens. Patients with osteosarcoma of the facial bone, as well as those identified as secondary lesions were excluded. The age of over 40 yr was selected arbitrarily in an effort to include only older patients. Consequently, of these 665 patients, 39 (5.9%) were included in the analysis. These older patients were compared to forty-three adolescent patients which review of medical records was available. The clinical information was obtained by reviewing the medical records. The institutional review board at our hospital accepted all protocols. Two evaluations were performed. In the first, an attempt was made to evaluate the possible prognostic factors such as gender, tumor location, size, serum alkaline phosphatase level, radiological findings, chemotherapy intensity, chemotherapy-induced tumor necrosis and surgical margin. The second evaluation involved determining whether any significant clinical differences existed between older patients and adolescents.

Neo-adjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy were given according to Rosen's T-10 regimen (4). Preoperative chemotherapy consisted of a weekly administration of high dose methotrexate (12 g/m2) for 2 consecutive weeks, followed by cisplatin (100 mg/m2), and doxorubicin (30 mg/m2). Two courses of this three-drug combination chemotherapy were followed by definitive surgery. All of the resected tumors were subjected to a pathological assessment for neo-adjuvant chemotherapy response. The histological response to chemotherapy was graded as "good" (≥90% tumor necrosis) and "poor" (<90% tumor necrosis). The good grade corresponded to grade III and IV of the descriptive classification proposed by Rosen et al. (4). Patients whose tumor exhibited more than 90% necrosis (good responders) received the same chemotherapeutic agents that they had been given before surgery. Patients with tumor necrosis of less than 90% (poor responders) received cisplatin, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and bleomycin. Ifosfamide (14 g/m2) was infused continuously for 7days with bleomycin (30 mg/m2).

The event free survival was defined as the time the patients remained free of disease (the absence of pulmonary or other metastases and local recurrence) after the primary tumor had been extirpated. The overall survival included all of the patients who had metastases, and were treated for this complication, and was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier survival curves. The impact of the prognostic factors was assessed using the log-rank test. The differences between the adolescent and older patients were assessed using a chi-square test. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The 39 patients ranged in age from 40 to 72 yr (mean, 53.15 yr). There were 22 females and 17 males.

Thirty-one cases were stage IIB (high grade with an extra compartment) according to the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society Staging System (5) and 8 cases were stage III (any grade with metastasis). The tumors were located on the bones of the extremities in 31 (79.5%) and on the axial bones in 8 (20.5%) patients. In the extremities, the most common location was the distal femur (n=12, 30.8%), followed by the proximal tibia (n=8, 20.5%), proximal femur (n=7, 18.0%), humerus (n=2, 5.1%) and others (n=2, 5.1%). For the axial bones, the most common site was the pelvis (n=7, 18.0%), which was followed by the sacrum (n=1, 2.6%).

Thirty-seven of the 39 cases were available to study the size of the lesion, which ranged in size from 6 to 23 cm, and the size was more than 10 cm in the greatest dimension in 24 (64.9%) cases, whereas the size was less than 9 cm in diameter in 13 (35.1%).

The radiological findings were interesting. Twenty-nine patients had radiographs available for study or an adequate detailed description in their medical records. According to these, 19 cases (65.5%) showed osteolytic lesions, 3 cases (10.4%) showed osteoblastic lesions, and 7 cases (24.1%) showed a mixed pattern. Periosteal reactions were observed in only 6 cases (20.7%).

The initial serum alkaline phosphatase level could be reviewed in 30 cases. Twenty-two cases had lower levels than the normal range, and 8 cases had higher levels.

Eleven cases (39%) were initially misdiagnosed. Misdiagnoses included a simple fracture (3 cases), giant cell tumor (3 cases), infection (2 cases), metastatic tumor (2 cases) and myositis ossificans (1 case). Misdiagnosed 11 patients were treated with routine conventional protocols, which we provide.

Complete chemotherapy treatment was defined as completion of chemotherapy to over 75% of the predetermined dosage. Chemotherapy was given to 22 patients. Complete chemotherapy was given to 16 of 22 patients, and incomplete therapy was given to 6 patients. Chemotherapy was not administered to 17 patients as a result of their poor systemic condition.

A documented grading of tumor necrosis after preoperative chemotherapy was available in 18 patients. Using tumor necrosis at or above 90%, which is consistent with an effective response induced by chemotherapy; a good grade of an effective response was observed in 3 cases (16.7%) and a poor grade was observed in 15 (83.3%) cases.

Thirty-three cases underwent surgery; 29 of the 33 cases underwent a wide excision; 6 cases developed a local recurrence after surgery. Four cases underwent a marginal or intra-lesional excision; 2 of these cases developed a local recurrence. The remaining 6 cases were treated without surgery due to an inoperable local condition or poor systemic condition.

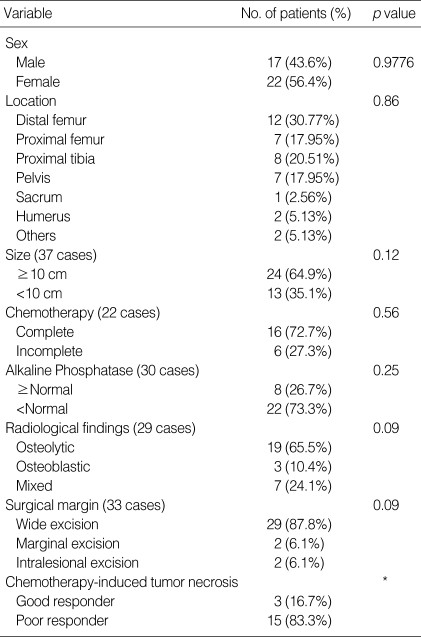

The institutional review of primary osteosarcoma in the older patients did not reveal any significant prognostic variables in terms of the gender, tumor location, tumor size, initial serum value for alkaline phosphatase, radiological findings, surgical margin, chemotherapy intensity and chemotherapy-induced tumor necrosis rate (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical data of 39 old age patients

*Statistical evaluation is not available on account of the disproportionate number of patients.

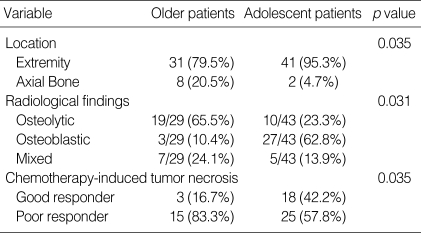

In a comparative study, the tumor location, chemotherapy-induced tumor necrosis and radiological findings for the older patients were statistically different from the adolescent patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistically significant comparisons between older patients and adolescent patients

For 31 cases in stage IIB, the actual 5 yr survival rate was 44.3%, and the disease free survival rate was 26.7%. Fifteen of the 31 cases developed metastases, which was detected from 2.8 to 74.5 months after the initial diagnosis (mean 19.8 months). For 8 cases in stage III, the actual 5 yr survival rate was 12.5%. The event free survival in the older patients was 17.8% at 110 months.

DISCUSSION

Most osteosarcoma patients are adolescents but there is an increasing incidence of older patients with osteosarcoma (6). Therefore, an analysis of older patients with osteosarcoma is noteworthy. Information regarding the clinical outcome of older patients with osteosarcoma has been based on reports from the United States and Europe; they indicate that most older patients with osteosarcomas have them as secondary lesions (2,3). However, a secondary osteosarcoma is rare in Asian countries. Most older patients with osteosarcoma in Asian countries are considered to be primary osteosarcoma. A few Asian reports (7,8) have revealed the characteristics of older patients with osteosarcoma. According to the report by Naka et al., including secondary osteosarcoma, age is not a poor prognostic factor and older patients should be treated similarly to younger patients with aggressive chemotherapy and complete surgical excision whenever possible (7). However, his paper was not based only on primary de novo osteosarcoma.

In 1999, Rhee et al. (9) evaluated 11 older patients with primary osteosarcoma, and concluded that there was no significant poorer survival by age among patients. However, they reported that the radiological patterns of multiple osteolytic lesions, and the predominantly fibroblastic appearance of tumors were particularly prevalent among older patients. Their findings were similar with this study but their results were not consistent with the results of this study. The different results might be due to a smaller study population as well as the inclusion of two patients with stage I osteosarcoma in Rhee et al.

In contrast to osteosarcoma in adolescents, occurrences in the axial bone (20.5% vs. 4.7%) were not uncommon. The tumor was more commonly located in the axial bones of the older patients than in the adolescent patients (p=0.035). Because of the characteristic site distribution, surgical treatment in the older patients is technically more difficult. The radiological characteristics of a primary osteosarcoma in older patients are probably associated with the frequent misdiagnoses. There was a predominance of osteolytic lesions and a frequent absence of a periosteal reaction (65.5%). In 3 cases, misdiagnosed as a giant cell tumor, the radiological features were quite similar to those of a typical giant cell tumor, showing osteolytic lesions without periosteal reaction (Fig. 1). These characteristic radiological features might be associated with the frequent misdiagnosis in this group.

Fig. 1.

Anteroposterior radiography shows an osteolytic lesion without periosteal reaction of the proximal tibia. This lesion was misdiagnosed as a giant cell tumor before biopsy.

In addition, the unusual sites of an osteosarcoma in older patients may also lead to a misdiagnosis. Therefore, the possibility of a primary osteosarcoma should be considered for osteolytic lesions without periosteal reactions in older patients, even though other diagnoses are more common in this age group.

Regarding the chemotherapy-induced tumor necrosis, 42.2% were good responders in the adolescent group but only 16.7% were good responders in the older patients (p=0.035). Preoperative chemotherapy was supplied in 18 patients, and the effect was poor in 15 (83.3%) of those. The poor response to chemotherapy might be due to a difference in tumor biology. Although, the meaning of the serum alkaline phosphatase level varies (10,11)., the high rate of low alkaline phosphatase levels and the low rate of osteoblastic radiological findings in this group may be related to this. According to Huvos (3), the subclassification of an osteosarcoma by histology examination revealed a clear preponderance of fibro-histiocytic and fibrous variants (38.5%). We suspect that osteosarcomas in older patients might have a different pathologic trend and this phenomenon produced different radiological features. However, this point is not certain until more detailed study is developed in the future. In addition, it is widely accepted that the pharmacokinetics in patients with an osteosarcoma are age related (12), and that the side effects associated with chemotherapy are more prominent in older patients (13).

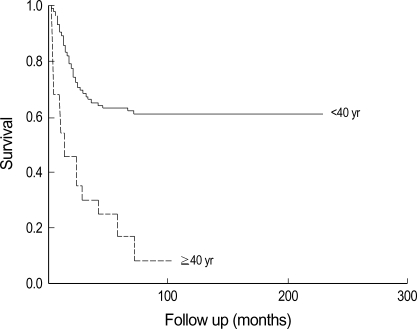

This paper examined only primary osteosarcoma in older patients. According to our results, older patients have a poorer prognosis than adolescents. The overall survival and event free survival rate in older patients was 39.5% at 104 months and 17.8% at 110 months. In contrast, it was 70.1% at 228 months and 61.6% at 228 months in adolescents (p<0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve between old age and adolescents patients shows significant differences. Older patients had a poorer prognosis.

The poor survival in older patients is most likely associated with a combination of unusual tumor locations, delayed diagnosis due to unusual radiological findings, difficulties with surgery and administration and poor response to chemotherapy. Therefore, careful attention should be paid to making an accurate diagnosis. In addition, new strategies including modified chemotherapy regimens will be needed to achieve a long-term survival for older patients with osteosarcoma.

References

- 1.Gurney JG, Severson RK, Davis S, Robison LL. Incidence of cancer in children in the United States. Sex-, race-, and 1-year age-specific rates by histologic type. Cancer. 1995;75:2186–2195. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950415)75:8<2186::aid-cncr2820750825>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimer RJ, Cannon SR, Taminiau AM, Bielack S, Kempf-Bielack B, Windhager R, Dominkus M, Saeter G, Bauer H, Meller I, Szendroi M, Folleras G, San-Julian M, Eijken JV. Osteosarcoma over the age of forty. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huvos AG. Osteogenic sarcoma of bones and soft tissue in older persons. A clinicopathologic analysis of 117 patients older than 60 years. Cancer. 1986;57:1442–1449. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860401)57:7<1442::aid-cncr2820570734>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen G, Caparros B, Huvos AG, Kosloff C, Nirenberg A, Cacavio A, Marcove RC, Lane JM, Mehta B, Urban C. Preoperative chemotherapy for osteosarcoma. Selection of post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy based on the response of the primary tumor to preoperative chemotherapy. Cancer. 1982;49:1221–1230. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820315)49:6<1221::aid-cncr2820490625>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enneking WF. A system of staging musculoskeletal neoplasms. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;204:9–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stark A, Kreicbergs A, Nilsonne U, Silfversward C. The age of osteosarcoma patients is increasing. An epidemilolgical study of osteosarcoma in Sweden 1971 to 1984. J Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72B:89–93. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B1.2298802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naka T, Fukuda T, Shinohara N, Iwamoto Y, Sugioka Y, Tsuneyoshi M. Osteosarcoma versus malignant fibrous histiocytoma of bone in patients older than 40 years. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis with special reference to malignant fibrous histiocytoma-like osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1995;76:972–984. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950915)76:6<972::aid-cncr2820760610>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okada K, Hasegawa T, Nishida J, Ogose A, Tajino T, Osanai T, Yanagisawa M, Hatori M. Osteosarcomas after the age of 50: a clinicopathologic study of 64 cases; an experience in northern Japan. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:998–1004. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhee SK, Woo YK, Kang YK, Song SW, Chung YG, Lee AH, Yoo JY, Chung DH. Osteosarcoma in patients older than 40 years. J Korean Bone Joint Tumor Soc. 1999;5:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacci G, Picci P, Ferrari S, Orlandi M, Ruggieri P, Casadei R, Ferraro A, Biagini R, Battistini A. Prognostic significance of serum alkaline phosphatase measurements in patients with osteosarcoma treated with adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 1993;71:1224–1230. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930215)71:4<1224::aid-cncr2820710409>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorpe WP, Reilly JJ, Rosenberg SA. Prognostic significance of alkaline phosphatase measurements in patients with osteogenic sarcoma receiving chemotherapy. Cancer. 1979;43:2178–2181. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197906)43:6<2178::aid-cncr2820430603>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang YM, Sutow WW, Romsdahl MM, Perez C. Age-related pharmacokinetics of high-dose methotrexate in patients with osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Rep. 1997;63:405–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimmick GG, Fleming R, Muss HB, Balducci L. Cancer chemotherapy in older adults. A tolerability perspective. Drugs Aging. 1997;10:34–49. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199710010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]