Abstract

Despite advanced effective prophylaxes, pulmonary complications still occur in a high proportion of all hematopoietic stem cell recipients, accounting for considerable morbidity and mortality. The aim of our study was to describe the causes, incidences and mortality rates secondary to pulmonary complications and risk factors of such complications following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). We reviewed the medical records of 287 patients who underwent either autologous or allogeneic HSCT for hematologic disorders from February 1996 to October 2003 at Samsung Medical Center (134 autografts, 153 allografts). The timing of pulmonary complications was divided into pre-engraftment, early and late period. The spectrum of pulmonary complications included infectious and non-infectious conditions. 73 of the 287 patients (25.4%) developed pulmonary complications. Among these patients, 40 (54.8%) and 29 (39.7%) had infectious and non-infectious conditions, respectively. The overall mortality rate from pulmonary complications was 28.8%. Allogeneic transplant, grade II-IV acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and extensive chronic GVHD were the risk factors with statistical significance for pulmonary complications after HSCT. The mortality rates from pulmonary complications following HSCT were high, especially those of viral and fungal pneumonia, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and idiopathic pneumonia syndrome.

Keywords: Infection, Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation, Graft vs. Host Disease

INTRODUCTION

Since the early 1960s, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has been used with increasing frequency for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant diseases. However, overall pulmonary complications, including infectious and non-infectious, was reported to occur in 40 to 60% of all HSCT recipients, which accounted for considerable morbidity and mortality (1). Moreover, mortality rates for HSCT recipients with pulmonary infiltrates requiring mechanical ventilation approach 90% (2). Conditioning regimen, reconstitution of the immune system, and prophylactic strategy for infection influence the incidence of pulmonary complications following HSCT (3). Infectious complications are more common in allogeneic HSCT recipients because of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) itself and the prophylactic or therapeutic immunosuppressive therapy for GVHD (4,5). As the incidence of infectious pulmonary complications has diminished as a result of effective prophylactic therapy, noninfectious pulmonary complications have emerged as a major cause of post-HSCT morbidity and mortality (6). The purpose of our study was to describe 1) the causes, incidence and mortality rates of pulmonary complications, and 2) the risk factors associated with pulmonary complications following HSCT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

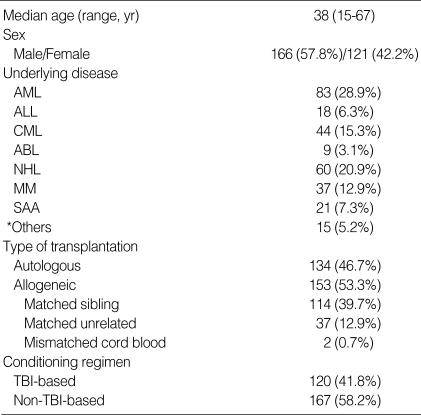

We reviewed the medical records of patients, who underwent HSCT for hematologic disorders from February 1996 to October 2003 at Samsung Medical Center. A total of 287 patients were enrolled. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of these patients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; ABL, acute biphenotypic leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; SAA, severe aplastic anemia; TBI, total body irradiation.

*Others, myelodysplastic syndromes, neuroblastoma, chronic EBV syndrome, idiopathic myelofibrosis, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, primary amyloidosis, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

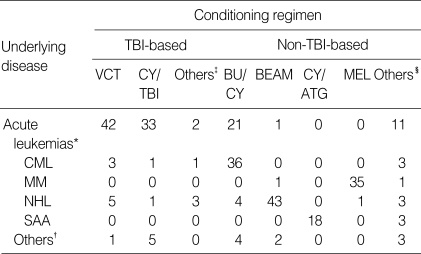

Autologous transplantation was performed in 134 patients and allogeneic transplantation in 153 patients (114 matched sibling donors, 37 matched unrelated donors, and 2 mismatched cord blood). Acute and chronic leukemias, malignant lymphomas, and multiple myeloma were the common underlying diseases. The conditioning regimens employed are summarized in Table 2. In matched sibling donor allogeneic transplantation (n=114), a combination of cyclosporine (CSP) and methotrexate (MTX) was most commonly used for GVHD prophylaxis (n=79). CSP alone was applied for patients at the age of 20 yr or less (n=8), and a combination of CSP, MTX and methylprednisolone (MP) was applied for patients at the age of 45 yr or more (n=10). In allogeneic transplantation with matched unrelated donor (n=37), a combination of CSP and MTX (n=17) and a combination of CSP, MTX and MP (n=9) were the most common GVHD prophylaxis regimens. The timing of pulmonary complications was divided into three categories: 1) pre-engraftment period, defined as less than 30 days after HSCT; 2) early period, defined as 30 to 100 days after HSCT; 3) late period, defined as over 100 days after HSCT. Pulmonary complications were divided into infectious and non-infectious categories. Infectious complications included not only microbiologically defined pneumonia, but also clinically defined bacterial pneumonia. A "clinically defined bacterial pneumonia" was defined as the presence of respiratory and infectious signs and symptoms, with pulmonary infiltrates on imaging studies, and the definite response of pneumonia to broad-spectrum antibiotics, but clinically significant microorganisms were not identified from blood and sputum cultures. To identify the cause of a pulmonary complication, invasive procedures such as bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), transbronchial lung biopsy, or open lung biopsy were performed if possible. Idiopathic pneumonia syndrome was defined as the presence of multilobar pulmonary infiltrates on imaging studies with no microorganism identified despite of invasive procedures. "Unknown etiology" was defined as the presence of respiratory and infectious signs and symptoms, with pulmonary infiltrates on imaging studies, but clinically significant microorganisms were not identified from blood and routine sputum cultures and pneumonia did not respond to anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, anti-viral and anti-Pneumocystis carinii agents. Patients whose disease was categorized as "unknown etiology" were unable to undergo invasive procedures due to poor physical condition or refusal to undergo such a procedure.

Table 2.

Conditioning regimens

CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; SAA, severe aplastic anemia; TBI, total body irradiation; VCT, VP-16 (etoposide), cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation; CY, cyclophosphamide; BU/CY, busulfan and cyclophosphamide; BEAM, BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine and melphalan; ATG, anti-thymocyte globulin; MEL, melphalan.

Acute leukemias*, acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute biphenotypic leukemia. Others†, BU/TBI, busulphan and total body irradiation; TT/TBI, thiotepa and total body irradiation; MEL/TBI, melphalan and total body irradiation; VACT, etoposide, cytarabine, cyclophophamide and total body irradiation. Others‡, CBV, cyclophosphamide, BCNU and etoposide; TT/Carbo, thiotepa and carboplatin; TT/CY, thiotepa and cyclophosphamide; ARA-C/CY/ATG, cytarabine, cyclophosphamide and anti-thymocyte globulin. Others§, myelodysplastic syndromes, neuroblastoma, chronic EBV syndrome, idiopathic. myelofibrosis, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, primary amyloidosis, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

Prophylactic antimicrobials

Antibiotics for bacterial prophylaxis were not routinely provided. Amoxicillin/clavulanate was administered for preventing infection with encapsulated organisms among allogeneic recipients with chronic GVHD for as long as active chronic GVHD treatment was administered. Nystatin or clotrimazole was given to prevent fungal colonization in the upper digestive mucosa during neutropenia; if patient did not tolerate them well, fluconazole was administered orally or intravenously. Weekly blood sampling for cytomegalovirus (CMV) shell vial culture and CMV antigenemia assay started at engraftment (absolute neutrophil count >0.5×103/µL) following allogeneic HSCT and continued until any immunosuppressive agent for the prevention or treatment of GVHD had been completed. Allogeneic recipients began preemptive treatment with ganciclovir, if CMV viremia or antigenemia was detected. Acyclovir prophylaxis was offered to all herpes simplex virus (HSV)-seropositive HSCT recipients to prevent HSV reactivation during the early posttransplant period. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia prophylaxis with oral trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole or aerosolized pentamidine was administered from engraftment until 6 months after HSCT for allogeneic recipients.

Treatment of infectious complications

Each infectious complication during neutropenic period was treated according to the guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents prepared by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (7,8). Antimicrobial agents were scrupulously chosen based on the cultures and serology tests for microorganisms and the clinical manifestations.

Statistical analyses

Clinical data were analyzed to determine whether the incidence of pulmonary complications was correlated with previously known risk factors such as age, sex, underlying disease type, transplant type, GVHD, and total body irradiation (TBI) using Student t-test, chi-square test, and a linear by linear association as univariate analysis. Binary logistic regression was used in multivariate analysis. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Pulmonary complications developed in 73 out of a total of 287 patients (25.4%). Among these 73 patients, 40 (54.8%) had infectious complications and 29 (39.7%) had non-infectious complications.

Infectious complications

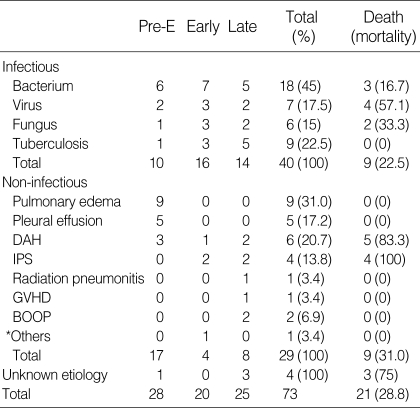

Table 3 shows the causes and mortality rates of infectious pulmonary complications. Bacterial pneumonia was the most common type of infection in all periods (45.0%) but was microbiologically documented from the blood or BAL fluid in only 4 patients. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was identified from the blood culture of 2 patients, Staphylococcus aureus from the blood culture of 1 patient, and Escherichia coli from the blood and BAL fluid culture of 1 patient. We failed to identify clinically significant microorganisms from blood, sputum or BAL fluid in the remaining 14 patients. Viral pneumonia developed in 7 patients. Five patients had CMV pneumonia and 2 had adenovirus pneumonia. The diagnosis of viral pneumonia was made with BAL (n=2), transbronchial biopy (n=2), or open lung biopsy (n=3). Only two patients with viral pneumonia were alive at the time of analysis. One patient with viral pneumonia died of a non-pneumonic event. Fungal pneumonia developed in 6 patients, all of who were diagnosed with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Five of the six patients with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis underwent open lung biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Despite intensive treatment with anti-fungal agents, two patients died. All patients with pulmonary tuberculosis were diagnosed by positive acid-fast bacilli stain or culture of either sputum or BAL fluid. All of the pulmonary tuberculosis patients survived. Compared to that of bacterial pneumonia, the mortality rates for viral and fungal pneumonia were very high (Table 3).

Table 3.

Causes and mortalities of pulmonary complications

DAH, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage; IPS, idiopathic pneumonia syndrome; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; BOOP, bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia. *Others, Bronchial stenosis.

Non-infectious complications

Table 3 shows the causes and mortality rates of non-infectious pulmonary complications. In the pre-engraftment period, pulmonary edema (n=9) and pleural effusion (n=5) were the most common non-infectious complications. These were the result of fluid overload related to the conditioning therapy. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (n=6) and idiopathic pneumonia syndrome (n=4) were also important causes of non-infectious complications. Nine out of the 10 patients succumbed to either diffuse alveolar hemorrhage or idiopathic pneumonia syndrome.

Complications caused by unknown etiology

Three (75%) of the 4 patients with infection of unknown etiology died despite of aggressive treatment with anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, anti-viral and anti-Pneumocystis carinii agents.

Mechanical ventilatory support

Thirty-four (47%) out of the 73 patients with pulmonary complications following HSCT required intensive care unit care (20 infectious, 11 non-infectious and 3 unknown etiology). Mechanical ventilation was provided for respiratory support in 23 patients (13 infectious, 7 non-infectious and 3 unknown etiology), but 21 patients died during mechanical ventilation support.

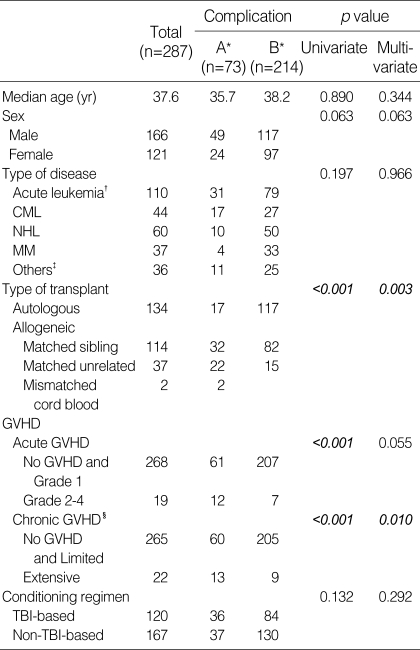

Risk factors

Table 4 outlines the risk factors associated with pulmonary complications following HSCT. Allogeneic transplant, the development of grade II-IV acute GVHD, and extensive chronic GVHD were the significant risk factors for the development of pulmonary complications following HSCT in univariate analysis (all p<0.001). In multivariate analysis, allogeneic transplant and extensive chronic GVHD were significant influential factors for pulmonary complications (p=0.003 and 0.010, respectively); however, grade II-IV acute GVHD revealed a trend for development of pulmonary complications without statistical significance (p=0.055).

Table 4.

Risk factors for pulmonary complications

CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; MM, multiple myeloma; NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; TBI, total body irradiation.

A*, presence of complication, B*, absence of complication; Acute leukemia†, acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute biphenotypic leukemia; Others‡, severe aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, neuroblastoma, chronic EBV syndrome, idiopathic myelofibrosis, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, primary amyloidosis, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; Chronic GVHD§, classified by Revised Seattle classification.

DISCUSSION

We confirmed the positive correlations between the type of transplant, the development of GVHD and the incidence of pulmonary complications following HSCT. As far as the relationship between underlying primary disease and the incidence of pulmonary complications was concerned, acute and chronic leukemias were more closely related to the development of pulmonary complications than multiple myeloma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma though this was not found to be statistically significant. This result might be due to the small number of patients in each disease category. In contrast to the results of other studies (9,10), TBI-based conditioning regimen was not a significant risk factor for the development of pulmonary complications after HSCT in our study. The majority of episodes of clinical radiation pneumonitis have been described in association with therapeutic radiation for solid tumors or lymphomas, but a few episodes were reported with low-radiation dose used in TBI (11). The development of clinical illness was uncommon as a direct result of TBI and fatal pulmonary complications after HSCT were not significantly different between TBI-based and non-TBI-based regimens (12). However, a direct or permissive role of radiation has been suggested in the development of infectious pneumonia or idiopathic pneumonitis.

Clinically significant microorganisms were isolated from the blood in only 4 out of the 18 patients (22.2%) with bacterial pneumonia in our study. Blood culture positive bacterial pneumonia constituted a small proportion of bacterial pneumonia in the setting of HSCT. Moreover, in our study, the etiology could not be evaluated in 4 patients with unknown etiology due to poor clinical conditions of the patients. No compound infectious complication was identified, which might be attributed to prophylactic administration of antimicrobials for HSCT recipients. The detailed pathophysiologies of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (13-17) and idiopathic pneumonia syndrome (18-21) have not been clarified yet, and the treatment options of these diseases are limited. In general, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage during the pre-engraftment period after HSCT results mainly from idiopathic etiologies and rarely from infections (13-17).

The incidences of pulmonary complications after HSCT have been well established in previous studies (1). Compared to previous reports, the incidence and mortality of pulmonary complications after HSCT were lower in our study (40 to 60% vs. 25.4% and over 30% vs. 28.8%, respectively), which may be due to the large proportion (46.7%) of autologous HSCT patients in our study.

In our study, the incidence of pulmonary complications was significantly lower in recipients of autologous HSCT compared to that of allogeneic HSCT recipients. Severe pulmonary complications occurred in 24% of allogeneic transplant patients and 2.9% of autologous transplant patients (p<0.001) (22). Recipients of autologous transplants had a lower probability of developing opportunistic pulmonary infections than did the recipients of allogeneic transplants (p<0.001) (23). It is believed that the low incidence of pulmonary complications in autologous transplant recipients result from the multiple factors such as the faster immunologic recovery, absence of GVHD or other alloreactive mechanisms, no use of immunosuppressive agents for GVHD prophylaxis or treatment. In the pre-antiviral era, CMV pneumonia developed at the rate of 40 to 50% among bone marrow transplantation patients and its mortality exceeded 90% (1,10). With the introduction of preemptive and prophylactic treatments for CMV following HSCT, the incidence of CMV pneumonia has dropped to 10.6% (24). A combination of ganciclovir and intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of CMV pneumonia contributed to the improvement of survival rate at 3 months to between 48% and 85% (25-27). However, the survival rates have decreased further with time. Viral pneumonia was one of the most fatal pulmonary complications after HSCT even with antiviral therapies following aggressive interventions in our study. Among the 73 patients with pulmonary complications following HSCT, 34 patients required intensive care and 21 patients died despite mechanical ventilation support in our series. In general, viral and fungal infections, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and idiopathic pneumonia syndrome were associated with high mortality.

HSCT is an effective and promising therapeutic tool for a number of malignant and non-malignant conditions. Its success, however, is occasionally limited by the high incidence of complications, especially those related to the pulmonary system. An early broncoscopy with BAL and transbronchial biopsy has been recommended for diffuse interstitial lung diseases (28-30) and a percutaneous fine-needle aspiration for focal lung lesions with excellent yield (31). However, prognosis is grave despite of early detection of the pathogen of pulmonary complications by invasive procedures. Considering the rapid clinical deterioration in these patients, an early aggressive diagnostic work-up should be pursued. Effective prophylaxis and empirical treatment are very important for high-risk group of HSCT recipients to prevent viral or fungal pneumonia.

It was confirmed in our study that allogeneic transplant, acute and chronic GVHD requiring treatment were important risk factors for pulmonary complications after HSCT. Therefore, a deliberate selection of transplant type and prophylaxis and timely treatment of GVHD are critical to minimize the mortality and morbidity from pulmonary complications after HSCT.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Debra Phillips, Pharm.D. for critical reading of the manuscript and editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Krowka MJ, Rosenow EC, 3rd, Hoagland HC. Pulmonary complications of bone marrow transplantation. Chest. 1985;87:237–246. doi: 10.1378/chest.87.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shorr AF, Moores LK, Edenfield WJ, Christie RJ, Fitzpatrick TM. Mechanical ventilation in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: can we effectively predict outcomes? Chest. 1999;116:1012–1018. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.4.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matulis M, High KP. Immune reconstitution after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation and its influence on respiratory infections. Semin Respir Infect. 2002;17:130–139. doi: 10.1053/srin.2002.33441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lossos IS, Breuer R, Or R, Strauss N, Elishoov H, Naparstek E, Aker M, Nagler A, Moses AE, Shapiro M. Bacterial pneumonia in recipients of bone marrow transplantation. A five-year prospective study. Transplantation. 1995;60:672–678. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199510150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boeckh M, Leisenring W, Riddell SR, Bowden RA, Huang ML, Myerson D, Stevens-Ayers T, Flowers ME, Cunningham T, Corey L. Late cytomegalovirus disease and mortality in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants: importance of viral load and T-cell immunity. Blood. 2003;101:407–414. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afessa B, Litzow MR, Tefferi A. Bronchiolitis obliterans and other late onset non-infectious pulmonary complications in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:425–434. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes WT, Armstrong D, Bodey GP, Bow EJ, Brown AE, Calandra T, Feld R, Pizzo PA, Rolston KV, Shenep JL, Young LS. 2002 guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:730–751. doi: 10.1086/339215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes WT, Armstrong D, Bodey GP, Brown AE, Edwards JE, Feld R, Pizzo P, Rolston KV, Shenep JL, Young LS. 1997 guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with unexplained fever. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:551–573. doi: 10.1086/513764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jules-Elysee K, Stover DE, Yahalom J, White DA, Gulati SC. Pulmonary complications in lymphoma patients treated with high-dose therapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:485–491. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyers JD, Flournoy N, Thomas ED. Nonbacterial pneumonia after allogeneic marrow transplantation: a review of ten years' experience. Rev Infect Dis. 1982;4:1119–1132. doi: 10.1093/clinids/4.6.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fennessy JJ. Irradiation damage to the lung. J Thorac Imaging. 1987;2:68–79. doi: 10.1097/00005382-198707000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartsell WF, Czyzewski EA, Ghalie R, Kaizer H. Pulmonary complications of bone marrow transplantation: a comparison of total body irradiation and cyclophosphamide to busulfan and cyclophosphamide. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00541-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Afessa B, Tefferi A, Litzow MR, Krowka MJ, Wylam ME, Peters SG. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:641–645. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200112-141cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pastores SM, Papadopoulos E, Voigt L, Halpern NA. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: treatment with recombinant factor VIIa. Chest. 2003;124:2400–2403. doi: 10.1016/s0012-3692(15)31709-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afessa B, Tefferi A, Litzow MR, Peters SG. Outcome of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1364–1368. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-792OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conces DJ., Jr Noninfectious lung disease in immunocompromised patients. J Thorac Imaging. 1999;14:9–24. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins RA, Linder J, Stahl MG, Thompson AB, 3rd, Haire W, Kessinger A, Armitage JO, Arneson M, Woods G, Vaughan WP. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in autologous bone marrow transplant recipients. Am J Med. 1989;87:511–518. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(89)80606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kantrow SP, Hackman RC, Boeckh M, Myerson D, Crawford SW. Idiopathic pneumonia syndrome: changing spectrum of lung injury after marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 1997;63:1079–1086. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199704270-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark JG, Hansen JA, Hertz MI, Parkman R, Jensen L, Peavy HH. NHLBI workshop summary. Idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after bone marrow transplantation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;6:1601–1606. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.6_Pt_1.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crawford SW, Hackman RC. Clinical course of idiopathic pneumonia after bone marrow transplantation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:1393–1400. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.6_Pt_1.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaguchi N, Takatsuka H, Wakae T, Okada M, Fujimori Y, Okamoto T, Kakishita E, Hara H. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia following stem cell transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2003;17:338–346. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2003.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho VT, Weller E, Lee SJ, Alyea EP, Antin JH, Soiffer RJ. Prognostic factors for early severe pulmonary complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7:223–229. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11349809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leung AN, Gosselin MV, Napper CH, Braun SG, Hu WW, Wong RM, Gasman J. Pulmonary infections after bone marrow transplantation: clinical and radiographic findings. Radiology. 1999;210:699–710. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.3.r99mr39699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nichols WG, Gorey L, Gooley T, Davis C, Boeckh M. High risk of death due to bacterial and fungal infection among cytomegalovirus (CMV)-seronegative recipients of stem cell transplants from seropositive donors: evidence for indirect effects of primary CMV infection. J Infect Dis. 2003;101:407–414. doi: 10.1086/338624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reed EC, Bowden RA, Dandliker PS, Lilleby KE, Meyers JD. Treatment of cytomegalovirus pneumonia with ganciclovir and intravenous cytomegalovirus immunoglobulin in patients with bone marrow transplants. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:783–788. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-10-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emanuel D, Cunningham I, Jule-Elysee K, Brochstein JA, Kernan NA, Laver J, Stover D, White DA, Fels A, Polsky B. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia after bone marrow transplantation successfully treated with the combination of ganciclovir and high-dose intravenous immune globulin. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:777–782. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-10-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt GM, Kovacs A, Zaia JA, Horak DA, Blume KG, Nademanee AP, O'Donnell MR, Snyder DS, Forman SJ. Ganciclovir/immunoglobulin combination therapy for the treatment of human cytomegalovirus-associated interstitial pneumonia in bone marrow allograft recipients. Transplantation. 1988;46:905–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder CL, Ramsay NK, McGlave PB, Ferrell KL, Leonard AS. Diagnostic open-lung biopsy after bone marrow transplantation. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:871–876. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(90)90194-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunagan DP, Baker AM, Hurd DD, Haponik EF. Bronchoscopic evaluation of pulmonary infiltrates following bone marrow transplantation. Chest. 1997;111:135–141. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain P, Sandur S, Meli Y, Arroliga AC, Stoller JK, Mehta AC. Role of flexible bronchoscopy in immunocompromised patients with lung infiltrates. Chest. 2004;125:712–722. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong PW, Stefanec T, Brown K, White DA. Role of fine-needle aspirates of focal lung lesions in patients with hematologic malignancies. Chest. 2002;121:527–532. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.2.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]