Abstract

Determining the structure of a small molecule bound to a biological receptor (e.g., a protein implicated in a disease state) is a necessary step in structure-based drug design. The preferred conformation of a small molecule can change when bound to a protein, and a detailed knowledge of the preferred conformation(s) of a bound ligand can help in optimizing the affinity of a molecule for its receptor. However, the quality of a protein/ligand complex determined using X-ray crystallography is dependent on the size of the protein, crystal quality and the realized resolution. The energy restraints used in traditional X-ray refinement procedures typically use “reduced” (i.e., neglect of electrostatics and dispersion interactions) Engh and Huber force field models that, while quite suitable for modeling proteins often are less suitable for small molecule structures due to a lack of validated parameters. Through the use of ab initio QM/MM based X-ray refinement procedures this shortcoming can be overcome especially in the active site or binding site of a small molecule inhibitor. Herein, we demonstrate that ab initio QM/MM refinement of an inhibitor/protein complex provides insights into the binding of small molecules beyond what is available using more traditional refinement protocols. In particular, QM/MM refinement studies of benzamidinium derivatives show variable conformational preferences depending on the refinement protocol used and the nature of the active site region.

Introduction

The majority of protein-ligand structures that are used in structure-based drug design (SBDD)1 efforts are obtained using X-ray crystallography. A crystal structure of a protein-ligand complex provides a detailed view of the spatial arrangement as well as detailing the interactions present between the ligand and the enzyme active site. For more reactive, short-lived species, like enzyme substrates, time-resolved crystallography is a unique tool that identifies structural changes that occur as a reaction proceeds, thereby facilitating the study of reaction intermediate.2–7

After the structure of a protein-ligand complex has been solved, the resultant information can be used to assist in the design of new molecules. In what is termed “induced fit” both the ligand and the protein target adjust their conformations (if necessary) in order to form the best complex possible given their mutual structural constraints.8–11 This information can be critical in many instances because both the protein and ligand can undergo significant conformational changes with respect to their free or uncomplexed forms. Hence, the accurate prediction of protein-bound conformations of small molecules is an essential aspect of SBDD. However, due to the nature of the small molecules studied in SBDD efforts typical methods used to refine these structures are less well evolved than those for the protein structures themselves.12,13 Hence, developing methods that can enhance our understanding of small molecules bound to proteins is of great contemporary interest.

Importantly, the available structures of protein-ligand complexes determined by X-ray crystallography are often used as reference structures to generate and validate pharmacophore models, docking algorithms and force fields.14 Recently, protein-ligand structures have been used to estimate the strain induced when a small molecule binds to a receptor yielding surprisingly large strain energies.15–17 However, an accurate understanding of the quantitative aspects of the conformational changes a ligand undergoes when it binds to a protein is still surprisingly elusive.18 The conformation of small molecules may change significantly when binding to a protein.19 Ideally, small molecules should not undergo significant conformational changes in order to avoid free energy of binding penalties upon complex formation.

The Cambridge Structural Database (CSD)20,21 can be used to assist in validating protein-ligand complexes in the Protein Data Bank (PDB)22–24 through a comparison of the “free” crystalline molecules relative to the structure observed in the complexed state.25 For example, conformational analyses based on the structures from the CSD have been used to validate conformational minima of molecules observed in protein active sites.26,27 The use of crystallographic data in this way complements gas-phase ab initio calculations since it gives insights into conformational preferences in condensed-phase situations.27–29 Crystallographic data also underpins many molecular-fragment libraries and programs for generating three-dimensional models from two-dimensional chemical structures. When modeling of ligand binding to metalloenzymes, the information from the CSD can be used for guidance of the preferred coordination number(s) and geometries for metal binding warheads.30 Crystallographically derived information has contributed to many life science software applications, including programs for locating binding ‘hot spots’ on proteins, docking ligands into enzyme active sites, de novo ligand design, molecular alignment and three-dimensional QSAR.31,32

Given the critical importance of understanding both the structure of a protein-ligand complex and the interaction(s) between the binding partners it is remarkable how little work has focused on accurately refining these complexes. For example, the topologies and parameters for ligands and inhibitors used in the current generation of X-ray refinement programs, such as X-PLOR/CNS33, REFMAC34 and SHELX35 generally do not have enough information to properly model small molecules during refinement against experimental crystallographic data. In general, the ligand electron density is often difficult to fit unambiguously in protein crystallographic studies using low to medium resolution data, which is the resolution range where a large portion of protein-ligand complexes are being solved today. Because of these issues distorted geometries for the ligand and significant clashes between protein and ligand atoms are not that uncommon.36 Hence, unusual ligand conformations in the PDB should be treated with caution and need to be confirmed using multiple experimental and theoretical methods.

Benzamidinium and benzamidinium (protonated form of the parent benzamidine) derivatives are competitive inhibitors widely found in inhibitors of serine proteinases like trypsin, thrombin and factor Xa.37,38 Given the similarity in this class of inhibitors and in the target proteins themselves benzamidinium derivatives offer an interesting compound series to develop and validate QSAR models and our understanding of protein-ligand interactions.39–42 The amidine group in benzamidinium is chemically similar to the guanidinium moiety of the Arginine (Arg) side chain.43 The interaction between the guanidinium from Arg and the carboxylate from Glu/Asp plays an important role in receptor-substrate and receptor-drug interactions seen in serine proteinases. Indeed, benzamidinium derivatives are known to be potent, nonpeptide antagonists or antimetastatic agents.44,45 In order to better understand the preferred conformation(s) of benzamidinium ions we have examined a series of inhibitor/protein complexes involving this class of compounds using ab initio QM/MM X-ray refinement protocols and have shown that the originally identified conformations are not always the preferred ones. Indeed, we find that there is a rich “bound” conformational preference for this deceivingly simple molecule and that the nature of the enzyme active site can stabilize conformations found to be unstable in the gas-phase.

Methods

1. Selection and analysis of benzamidinium containing protein-ligand complexes

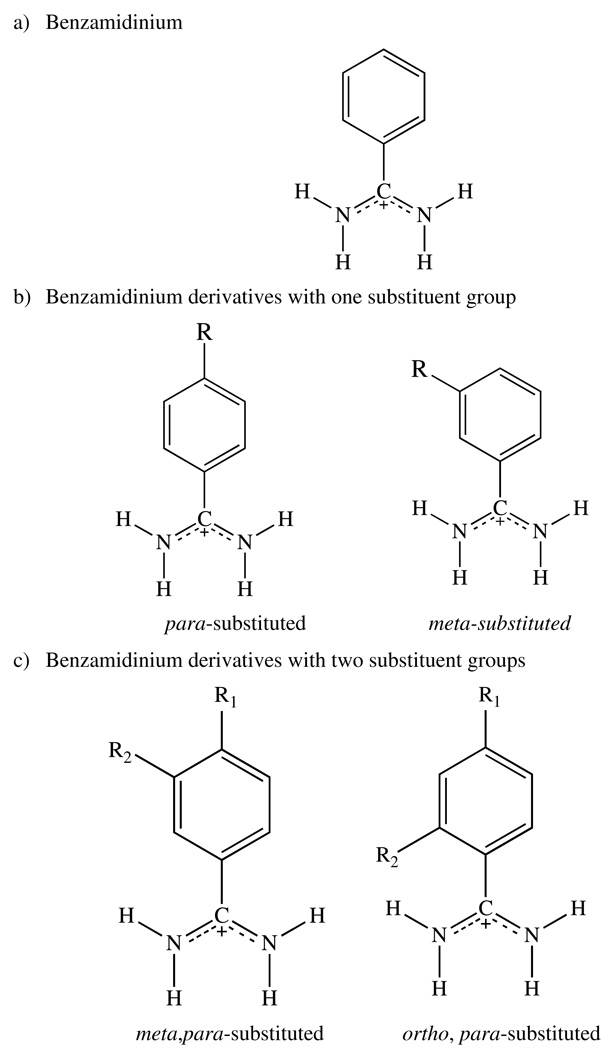

Prior to refining proteins complexed with benzamidinium and benzamidinium derivatives (shown in Figure 1) we carried out an analysis of the PDB for this class of protein-ligand complex. For this analysis the ligand must contain a benzamidinium moiety without multiple binding conformations due to crystallographic disorder, defined as partial occupancy for any atom from the ligand. The structures with crystallographic resolution below 1.5Å, with hydrogen atoms defined in the PDB, were also excluded from our selection. Please note that the benzamidinium moiety can occur multiple times in a ligand and these occurrences were counted as independent observations.

Figure 1.

Structures of benzamidinium and benzamidinium derivatives found in protein-ligand complexes

2. QM/MM and MM X-ray refinement of select protein-ligand complexes

The deposited PDB coordinates of 1RKW, 1RPW and 1Y3X served as the starting geometries for our QM/MM refinements.46,47 The 1RKW and 1RPW QacR (quaternary ammonium compound repressor) dimer structures, had resolutions of 2.62Å and 2.90Å, respectively. In our calculations only one subunit bound with a ligand was used in the refinement while the other subunit was kept fixed. The sulfate molecules were also kept fixed during the refinement process, while crystal waters were included in the refinement.

The 1Y3X trypsin-ligand structure has a higher resolution of 1.7Å. There are multiple conformations given for several of the trypsin side chains; however, these side chains are remote from the ligand binding, so in the QM/MM refinements only the main side-chain conformer was considered.

Due to system size limitations of ab initio methods, the QM region included the ligand and polar residues and/or water molecule within 3Å of the ligand itself. The Hartree-Fock (HF) level of theory with the 6–31G* basis set was the ab initio method used for the QM region in all cases. All the reflections downloaded from the PDB were considered, of which 5% of the reflections were randomly extracted and used as an external validation set. The QM/MM energy refinements were done using AMBER 1048 combined with our in-house ab initio code QUICK.49 The X-ray target function was evaluated by CNS (Crystallography and NMR System)33. The energy target function used in the QM/MMM refinements are given by equation 1 below:

| (1) |

Where wa is the weighting factor for the X-ray signal (we generally use a range of 0.1–1.0, but higher values can be used), EQM/MM is the QM/MM energy and gradients of the system and EX-ray is the pseudo energy function obtained from CNS along with the gradients. Thus, the gradients from the QM/MM region were merged with the X-ray gradients in order to update the coordinates in the minimization process.

In order to determine the dependence of the ligand conformation on the energy function scheme used in the refinement, the traditional MM based refinements using Engh-Huber parameters50 were also carried out. The topology and parameter files used for the ligands within the CNS (Crystallography and NMR System)33 program were obtained from the Hetero-compound Information Centre-Uppsala51,52 (Hic-Up sever: http://alpha2.bmc.uu.se/hicup/) as was done previously in the reported QacR refinements.53 Each refinement took about 600–700 refinement steps and each step involved ~60–80 atoms and required 40–50 minutes per cycle on a single 2.4 GHz AMD cpu. These are long runs, but we are parallelizing the code as well as trying different minimizers (we are using AMBER’s conjugate gradient optimizer) to reduce the number of refinement cycles in order to significantly decrease the refinement run times.

3. Benzamidinium torsion profile calculations

The torsional profiles were calculated using Gaussian 03.54 The torsion profiles for free benzamidinium and hydroxyl-substituted benzamidinium were calculated using the 6–31G* and aug-cc-pvtz basis sets at the HF and MP2 levels of theory. In order to obtain the torsion energy profiles, torsional scans were carried out by varying the N-C-C-C (the last two carbon atoms come from the phenyl ring, while the first two atoms are from the amidine group) torsion angle between 0° and 180°, in 10° intervals. For each structure along the torsion profile, a constrained energy minimization was carried out at fixed N-C-C-C torsion angles, while relaxing all other geometric variables.

In order to obtain insights into the conformational preferences of the bound benzamidinium derivatives and to further verify our QM/MM refinement results, we carried out active site cluster calculations that examined the N-C-C-C torsion angle. The model structures were built from crystal structures taken from the PDB (PDB ID’s: 1RKW, 1RPW, 1Y3X). Hydrogen atoms were added and then optimized initially using the SANDER module from the AMBER suite of programs. In order to preserve protein-ligand interactions, protein atoms with van der Waals contacts with the ligand were included in the calculations. The resultant cluster models are shown in Figure 2. Starting with these geometries, only the atoms involved in the N-C-C-C torsion angle and the attached hydrogen atoms were allowed to freely rotate, while the remaining atoms were kept frozen at their original positions. These gas-phase cluster calculations were done at the HF/6–31G* level of theory in order to match the method and basis set used in the QM/MM refinement studies themselves. These calculations were only used to give qualitative insights into the conformational preferences around the initial structure. This is because of the fixed geometries that were used. To examine the role geometric relaxation plays MD simulations were carried out.

Figure 2.

Model cluster structures used in the torsion profile calculations (hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity)

4. Molecular dynamics simulations

The QacR-pentadiamidine and QacR-hexadiamidine X-ray structures (PDB code: 1RKW and 1RPW, respectively) were used as the starting point for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using the AMBER force field, ff99sb55, for the protein atoms and gaff56 for the ligands. In order to investigate the benzamidinium torsional angle preference in the protein-ligand complex, we had to re-parameterize the force field for the dihedral angle between the amidine group and the phenyl ring (N-C-C-C torsion) using the energy profile obtained from high-level quantum mechanical calculations. The ligand partial charges were derived from a two-stage restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) fitting procedure.57 The entire protein-ligand complex, including all crystallographic waters, was solvated in an octahedral TIP3P58 water box with each side at least 8Å from the nearest the solute atom. Applying a uniform neutralizing plasma neutralized the net charge of the entire system. The SHAKE algorithm was employed to constrain bonds X-H bonds to their equilibrium values.59 The systems were minimized and then gradually heated up from 0K to 300K with slowly decreasing weak restraints on the heavy atoms of the complex. During the last step of equilibration, the restraints were removed entirely, and the production simulations were carried out at 300K for 8 ns with a 2 fs time step. Constant temperature was maintained using a Berendsen temperature bath with a coupling strength of 1.0 ps.60 Snapshots for subsequent analysis were taken every 2 ps. All simulations were carried out using the PMEMD module from the AMBER package.48

Results and Discussion

1. Observed conformations of benzamidinium and benzamidinium derivatives in protein-ligand complexes

The benzamidinium or benzamidinium derivatives included in the PDB can be divided into 3 classes based on the substitution of the parent benzamidinium: a) the unsubstituted amidine, benzamidinium; In this class, there were 87 crystal structures with a total of 153 benzamidinium moieties present in these structures. Please note that the same inhibitor may occur multiple times in one crystal structure at different positions. However, the inhibitors with disordered conformations were excluded from the study. b) One substitution at the para or meta positions of benzamidinium. The ortho-substituted benzamidinium was not observed in the crystal structures from the PDB databank. 46 ligands were substituted at the para-position, including several bivalent dibenzamidinium derivatives. The identities of the four bivalent dibenzamidinium derivatives are abbreviated as BBA61,62, PNT46, DID46, BRN (PBD ID: 2GBY), respectively. In these structures, all substitutions are at the para positions. There are 14 crystal structures, which contain one substituent in the meta-position. In the structures 1Y5A and 1Y5U, both p- and m- substitutions were observed in one inhibitor. c) Two substituents on the parent benzamidinium. The two substituent motifs can have three possible combinations: m, p-, o, p-, or m, o- derivatives. No inhibitor with both o- and m- substituents was found in the PDB. Only one inhibitor with p- and o- substitution was observed (PDB ID: 1YGC).63 The intramolecular interaction (2.53Å heavy atom-heavy atom distance) between the oxygen atom of the ortho-hydroxy group and the amidine nitrogen atom in the inhibitor, G17905, introduces structural and energetic constraints to the rotation of the amidine group. Hence, G17905 will be excluded from our statistical analysis. Six protein-ligand structures were found, in which the inhibitors have substituents at the p- and m- positions of benzamidinium.

In structure-based drug design, important intramolecular geometric parameters are the torsion angles around rotatable bonds, since they influence the overall shape of a molecule far more than do the bond lengths and valence angles. The main conformation difference for the benzamidinium containing compounds is the torsion angle formed by the N-C-C-C atoms (the latter two C atoms come from the phenyl ring, while the first two atoms come from the amidinium moiety). The conformational histograms of this torsion angle are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Conformational preference distributions observed in benzamidinium containing PDB structures

The experimentally found conformational distribution for benzamidinium from the PDB indicates two major preferences for the dihedral angles. The most frequently encountered one is the planar conformation, in which the torsion angles fall into the range of −10° −10°. The second one is the twisted conformation, which lies outside the previous range (>10° and <−10°). No relationship between the resolution of the structures and the number of occurrences of a specific torsional angle was observed. Both for unsubstitituted and substituted benzamidiniums similar torsional preferences were observed (see Figures 3a and 3b).

The preferred conformation of putative ligands obtained from small-molecule crystal structure data can also be used to validate the observed conformations found in protein-ligand complexes.8,10, 15 Sometimes the torsion distributions of molecular fragments in the CSD compared to the corresponding fragments in protein-bound ligands are similar, which suggests geometry distributions in small molecule crystal structures generally serve as useful guides to geometric preferences in protein-ligand complexes. However, the structures of benzamidinium and benzamidinium derivatives found in the CSD are different from what we observed in protein-ligand complexes.64 Only the non-planar conformation was observed. The average value is 33° with lowest value being 15° and the highest 55°. As we mentioned before, due to limitations of the X-ray experiment itself, the structure factors and the refinement procedure, the preferred or observed conformation of protein bound ligands may contain some uncertainties. Importantly, structure-based drug design relies heavily on experimental protein structures, taken from the PDB, so understanding the accuracy of the representation of a given protein-ligand complex is critical for success. Hence, it is worth taking a closer look at predicted protein-benzamidinium geometries in order to determine whether the wide range of torsional preferences are due to the nature of the complexes or due to shortcomings of refinement protocols.

2. QM/MM refinement on protein-ligand complexes

The QM/MM approach has been extensively used to study a number of chemical and biological problems.65–67 This method is typically applied when QM methods are too expensive to use on the entire system while at the same time MM methods themselves are unable to provide an accurate representation.68–71 Generally, this involves the study of reactive process, but not always. For example, QM/MM methods have been used in X-ray refinement studies in order to improve local geometries or to determine the protonation status of metal-bound ligands.72–82 In this study, we also used the QM/MM refinement method to enhance our understanding of the preferred ligand conformation in selected protein-ligand complexes.

The first two structures we examined were QacR-ligand complexes where two benzamidinium moieties were either connected by a pentyl or hexyl linker (shown in Figure 4a and 4b).46,53,83,84 Each ligand in 1RKW and 1RPW has two positively charged benzamidinium groups bound to QacR in different ways. It’s interesting that each torsion angle shows different preferences upon binding to different residues from QacR (from 0°~70°). The drug-binding pocket of QacR is quite extensive and has been described as having two independent but overlapping drug-binding sites that are designated the rhodamine 6G(R6G) and ethidium (Et) binding sites. A key feature of the binding pocket is the presence of several glutamates and a large number of aromatic residues. Combinations of these residues are used to define the specific small molecule-binding sites and provide maximal shape, chemical, and electrostatic complimentarity.

Figure 4.

Structures selected for detailed ab initio QM/MM refinement

The structure of the QacR-pentadiamidine complex was refined at 2.6Å resolution. In the original crystal structure, the pentadiamidine molecule was significantly twisted about its central linker. In the binding site 1 for pentadiamidine (PNT, shown in Figure 5a), no Glu or Asp residues lie within van der Waals/hydrogen contact to the positively charged benzamidinium group. However, a number of hydrogen bonds are formed with neutral residues via oxygen atoms. The nearest contacts were made with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Ala153 and the side chain hydroxyl oxygen of Tyr127, both of which engaged in hydrogen bond interactions with the amidinium group. The side chain carbonyl oxygen of Asn157 and the hydroxyl oxygen of Ser86 were also proximal to the benzamidinium moiety and contributed to the overall negative electrostatic character of Site 1. At the other end of the pentadiamidine-binding site (designated as site 2 – see Figure 5b), the benzamidinium moiety forms a Pi-stack with Tyr93 (Tyr93 not shown for clarity) along with several hydrogen bonding interactions. Glu63 and Glu67 both form hydrogen bonds with the positively charged benzamidinium moiety. One solvent molecule was also observed in the site 2 pentadiamidine-binding pocket.

Figure 5.

Select protein-ligand contacts. For a)-e), the residues in contact with the ligand in the active site are yellow sticks, while the ligands are shown as green sticks. The oxygen atoms in water molecules are given as red spheres. All other residues are grey. Black dashed lines indicate hydrogen bond interactions. O and N atoms are colored red and blue, respectively. All structures are taken from the PDB

The preferred value for the dihedral angle of the benzamidinium moiety in each binding site is planar. However, QM/MM refinement shows different preferences in the QacR-PNT complexes. In the PNT-QacR complex (See Figure 6 - selected refined structures at wa=0.8), the torsion angle becomes 34° in binding site 1 and 31° in binding site 2, whereas the torsion angles from the MM refinements are both around 0°. The end-to-end length of PNT is 16.03Å, which is shorter than the value obtained after MM refinement (17.55Å). The distance between N1 of PNT and Ser86/OG, N2 of PNT and Asn157/OD1 are shorter than the ones obtained from the MM refined structure. The nitrogen atom of Asn157 moved away from the N2 atom of PNT by 0.9Å thereby reducing repulsive interactions between the two nitrogen atoms after QM/MM refinement. In binding site 2, the two nitrogen atoms from the amidinium group of PNT after QM/MM refinement are much closer to the negatively charged carboxylate oxygen atoms from Glu63 and Glu57, which increases favorable electrostatic interactions between the ligand and protein. The water molecule stays at nearly the same location in both refinements.

Figure 6.

View of the 2Fo-Fc difference electron density of PNT contoured at 1.0 σ at wa=0.8. The difference density is shown as a blue mesh, and the underlying structure is shown as a stick model

The QacR-hexadiamidine (DID, shown in Figure 5c and d) complex was refined at 2.9Å resolution, and shows a very different binding mode from PNT. The residues from the R6G (Figure 5c) pocket include residues Glu57, Gln64 and Tyr93. Phe162’ (Figure 5d) and the carboxylate of Glu120 interacts with the amidinium group within the Et binding site. In the Et pocket Asn154 contributes polar contacts between QacR and DID. Asn157 also has non-polar contacts with the phenyl ring. A water molecule was also found in the Et binding pocket that was involved in water-mediated protein-small molecule interactions. The observed torsion angle for the benzamidinium fragment is −66°, indicating a very different conformational preference for this torsion angle in the Et binding site, while the same torsion angle is 0° in the R6G binding site (see Figure 7). These divergent conformational preferences for the two torsion angles were still observed in the structure after QM/MM refinement starting from the original crystal structure. For the selected structure at wa=0.8 after QM/MM refinement, the torsion angle preference is about −4° at the R6G binding site and −80° at the Et binding site. Compared to the structures obtained from the PDB and MM refinement, the R6G binding site amidinium group is closer to the active site residues, indicating stronger interaction between the ligand and protein in the binding site. Whereas, in the Et binding site, the distances between atoms from the ligand and protein residues are in between the distance observed from the PDB and re-refined MM structure. The planar conformation obtained from the MM re-refinement weakens the interactions between the ligand and protein active site.

Figure 7.

View of the 2Fo-Fc difference electron density of DID contoured at 0.5 σ at wa=0.8. The difference density is shown as a blue mesh, and the underlying structure is shown as a stick model

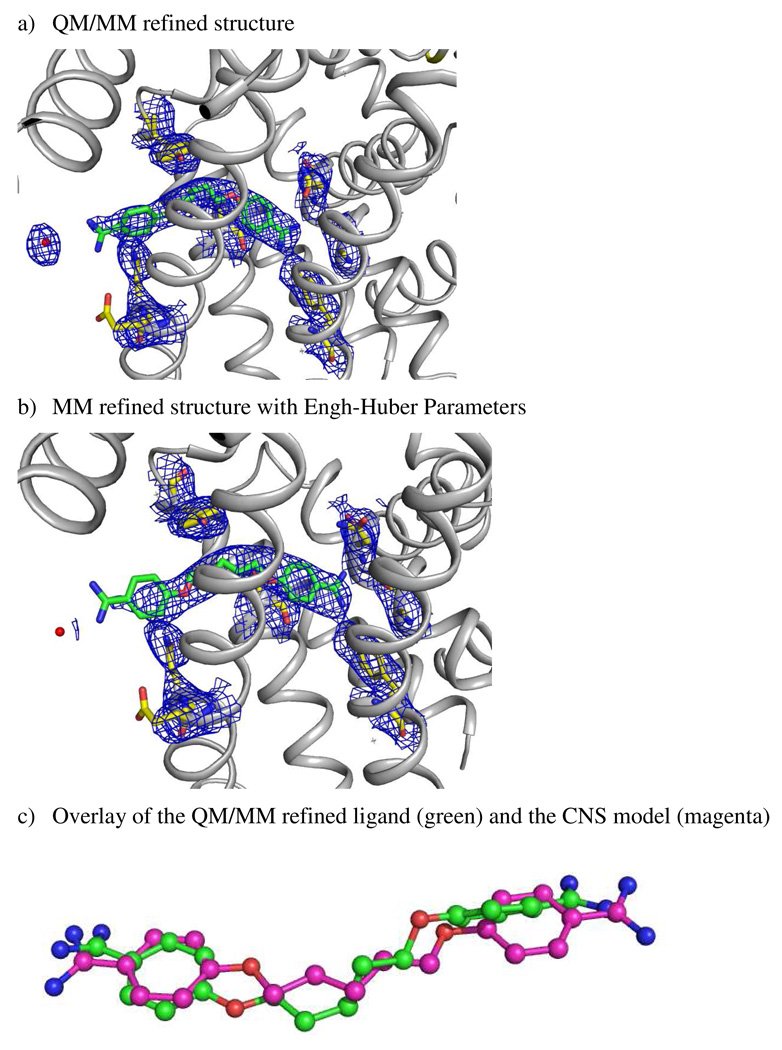

The 1Y3X crystal structure was originally refined to 1.7Å resolution. Each amidinium nitrogen atom from the UIB ligand (Figure 5e) makes hydrogen bonds to carboxylate oxygens of Asp189. One of the nitrogen atoms forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl of Gly219, while the second nitrogen forms a hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl oxygen and backbone carbonyl oxygen atom from Ser190. A water molecule also makes a hydrogen bond to this nitrogen atom and completes the hydrogen bond network between the benzamidinium fragment and the protein. After QM/MM refinement (see Figure 8a), the torsion angle is around 25°, which is a different from the structures refined (Figure 8b) with MM (torsion angle is about 0°). No significant changes were observed for the corresponding distances between the benzamidinium fragment and protein residues after both refinements.

Figure 8.

View of the 2Fo-Fc difference electron density of UIB contoured at 1.0 σ at wa=0.8. The difference density is shown as a blue mesh, and the underlying structure is shown as a stick model

The QM/MM refinements on the three selected protein-benzamidinium derivative complexes show distinctly different preferences for the benzamidinium torsion relative to the deposited structures as well as re-refined MM structures. When comparing the structure quality of the refinements carried out using different methods, such as the electron density maps for the ligand (shown in Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8) and the R and Rfree values (listed in Table 1), it is clear that the ligand structure after QM/MM refinement better fits the observed electron density than the one refined using a MM potential. Even though the R and Rfree factors are indicators of global structure quality we still observe that the QM/MM refined structures have better R and Rfree values. The local structure for the small molecule ligands have also been greatly improved by QM/MM based refinement methods. The real space R-values for the small molecule ligands (listed in Table 1) have lower values than those obtained after MM refinement. Taken together this in itself suggests that QM/MM based refinement is a very useful tool in improving the local structure quality for small molecule ligands.

Table 1.

X-ray Refinement Parameters for the MM and QM/MM based Refinement Studies.

| Ligand | PDB ID | wa | Methods | R | Rfree | Real Space R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNT | 1RKW | 0.8 | MM | 0.237 | 0.243 | 0.252 |

| QM/MM | 0.233 | 0.237 | 0.151 | |||

| DID | 1RPW | 0.8 | MM | 0.254 | 0.286 | 0.345 |

| QM/MM | 0.246 | 0.259 | 0.302 | |||

| UIB | 1Y3X | 0.4 | MM | 0.177 | 0.190 | 0.111 |

| QM/MM | 0.184 | 0.203 | 0.085 | |||

3. Computed torsion profiles

The refinement studies summarized above yielded contradictory results for the preferred conformation of benzamidinium derivatives when bound to a receptor. Table 2 summarizes the observed torsion values from the PDB, for CNS MM and CNS QM/MM refinement. A quick review of this table indicates that depending on the refinement protocol different results can be obtained. For example, for the PNT ligand the PDB and CNS MM refine structure gives nearly planar torsion angles, while the QM/MM model prefers rotated conformations of ~30°. From small molecule X-ray studies on benzamidinium and related derivatives (noted above) the value for this torsion was found to be on average ~33° in the crystalline phase. In order to better understand the conformational preferences we first calculated the torsion profile for the benzamidinium and p-hydroxybenzamidinium ion using ab initio QM calculations. In order to include the active site context we also carried out a series of QM calculations on the ligand with residues that are in close contact using ab initio methods as well.

Table 2.

Selected Torsion Angles Obtained from Different Refinement Procedures

| Ligand Methods | Torsion Angles (°) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNT | Site 1 | Site 2 | |||

| N1-C9-C4- | N2-C9-C4- | N1*-C9*-C4*- | N2*-C9*-C4*- | ||

| C3 | C5 | C3* | C5* | ||

| PDB | 1.60 | 1.45 | 0.46 | −0.02 | |

| QM/MM | 34.06 | 33.19 | 25.55 | 31.09 | |

| CNS | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.11 | −0.02 | |

| DID | Et | R6G | |||

| PDB | −66.16 | −66.14 | −0.30 | 0.15 | |

| QM/MM | −79.79 | −74.93 | −4.34 | −0.87 | |

| CNS | −71.34 | −69.46 | −0.02 | 0.00 | |

| UIB | PDB | −2.11 | −1.46 | ||

| QM/MM | −25.65 | −24.67 | |||

| CNS(MM) | −0.38 | −0.34 | |||

The results from our ab initio gas-phase calculations, using different levels of theory, are shown in Figures 9a and b. All the potential energy profiles for rotation of this dihedral angle showed a minimum at +40° and identically at 140° (or −40°) due to symmetry, which agrees with other theoretical studies.42 The energy difference between our best level of theory (MP2/Aug-ccpvtz) and HF/6–31G* at 90° is ~0.5 kcal/mol and at the planar conformation (0 or 180°) the difference is ~1.5 kcal/mol. Increasing the basis set size stabilizes the planar conformation, but even so the barrier to rotation is ~2.5 kcal/mol, while the orthogonal structure is slightly higher at ~3.3kcal/mol. Adding a hydroxyl substituent increases the orthogonal barrier height by a small amount (~0.2 kcal/mol for the meta derivative) to 1kcal/mol for the para derivative. The effect on the planar conformations is generally small except for the ortho derivative where intramolecular hydrogen bonding interactions alter the torsion profile significantly (see Figure 9b). Nonetheless, for the para derivatives refined herein it is clear that the gas-phase energy minimum is ~30°−40°.

Figure 9.

The torsion profiles obtained from different levels of theory for the benzamidinium and p-hydroxybenzamidinium ions

From the gas-phase torsion profiles it is clear that a twisted conformation is preferred for the parent compound, but benzamidinium based ligands found in the PDB show various conformational preferences when bound to a protein receptor (see Figure 3). In the majority of cases, the flexible ligand binds at a higher energy conformation than found from our gas-phase computations or in small molecule crystal structures. However, due to limited X-ray resolution and force field parameter issues for unusual ligands encountered in protein crystallography, it’s difficult to know whether or not the predicted ligand conformation obtained from X-ray refinement is correct or is biased. In order to delve into this further we have carried out in situ conformational analyses based on the fragment regions shown in Figure 2. In these calculations we only rotated the torsion and then computed the energy. Hence, the resultant energies are high because we did not energy minimize the system, but even these qualitative calculations provided useful insights.

From our cluster QM calculations we find that the QM/MM refinement structures always correspond to the global energy minimum for the ligand in its bound state (see Figures 10a–f). From Figures 10a and b it is clear that for the PNT ligand both in sites 1 and 2 prefer the twisted conformation. The situation for the DID ligand is the most interesting case in that both terminal benzamidinium groups adopt high-energy conformations. The R6G sites is nearly planar (see Figure 10c and Table 2), which from our gas-phase computations is 2-3kcal/mol higher in energy that the slightly twisted conformation. Interestingly, the Et binding site of the molecule twists to ~80°, which is ~3–4 kcal/mol higher than the preferred twisted conformation (see Figure 9b) seen in our ab initio calculations. Hence, in contrast to the PNT ligand we conclude that the DID ligand binds to the active site in a significantly strained conformation.

Figure 10.

Cluster torsion energy profiles for the bound ligands

For the Et binding site hydrogen bonding interactions between Glu120, the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom from Phe162’ and the side chain carbonyl oxygen of Asn154 are sufficient to distort the preferred conformation of the benzamidinium group. In the R6G binding site of DID, the amidinium group has several close contacts with the active site residues. Unfavorable interactions with the side chain amide group of Gln 64 coupled with favorable interactions with the carboxylate ion of Glu57 force the benzamidinium moiety to adopt the planar conformation as the global energy minimum.

For UIB we observe the expected behavior in that the benzamidinium group adopts the twisted conformation in the QM/MM based refinement. Like the PNT case the CNS MM and PDB structures adopt the incorrect planar conformation.

5. The torsion angle distributions obtained from MD simulations

Using our ab initio computed torsion profile we built an AMBER force file model in order to carry out MD simulations on the PNT and DID complexes to get a sense of how flexible the binding sites might be and to further corroborate our QM/MM refinement results. Previous MD simulations of bovine trypsin complexed with benzamidinium have been reported by using CHARMM22 force field85 and TIP3P water model58 indicated that the preferred torsion value is ±25° and that the planar conformation obtained from crystallographic refinement is an average of two symmetric, nonplanar conformation.40

Figure 11 and Figure 12 show that the benzamidinium dihedral angle distributions for both binding sites in the QacR-pentadiamidine (PNT) and QacR-hexadiamidine (DID) complexes, respectively, during the MD simulations. The N-C-C-C torsion angle in binding site 1 of PNT is maintained at around 30° whereas N-C-C-C torsion in site 2 is maintained at a 40° torsion angle throughout the entire 8 ns production simulation. These conformations are significantly different from the planar structures reported in the PDB X-ray structures, but they are similar to our QM/MM refined structure. In our MD simulation on DID, the torsion angle value in the R6G site is on average ~10°, indicating the benzamidinium moiety is nearly planar. The benzamidinium in the Et site is twisted with a dihedral angle of −40°. This observation matches the X-ray structure and our QM/MM refined structures in the sense that the twisted conformation is preferred, but the MD simulation has allowed the active site to relax for the much more twisted conformation predicted from the QM/MM refinement study. Nonetheless, the MD results confirm the results from the QM/MM refinement studies. Moreover, they do not suggest that the observed planar structures arise due to the sampling of two symmetrically related structures as was observed in earlier MD simulations.

Figure 11.

Dihedral angle distribution of the benzamidinium fragment in the QacR-pentadiamidine complex taken from an 8ns MD simulation

Figure 12.

Dihedral angle distribution of the benzamidinium fragment in the QacR-hexadiamidine complex taken from an 8ns MD simulation

Conclusions

In this manuscript we have shown that QM/MM based X-ray refinement can improve the analysis of protein-ligand complexes both by improving R and Rfree values and by providing a more accurate representation of the intra and intermolecular interactions of the ligand with itself and its environment. The reason why this approach succeeds depends on the resolution of the primary X-ray data and the ability of standard MM potentials within refinement programs to handle a specific pharmacophore. At high resolution defects in a given MM potential can be overwhelmed by the X-ray signal, while in lower resolution cases defects in a MM model can cause problems.

For benzamidinium and benzamidinium derivatives examined in detail herein the protein-ligand complexes obtained from the PDB were found to have a strong preference for the planar conformation (see Figure 3a and b). However, our QM/MM refinement studies of benzamidinium derivatives suggest that the ligand conformation presented in the PDB may not correspond to the “preferred” energy minimum and that this is, at least, partially due to the choice of MM potential used during the course of refinement. We find that QM/MM refinement of these complexes locally improved the ligand structure and tended to yield refined structures with the preferred (low energy) non-planar conformation. Importantly in cases where the active site environment imposes constraints on the “preferred” conformation the QM/MM approach is able to adapt to these perturbations. Using our gas-phase QM calculations we built improved MM potentials to carry out MD simulation studies of QacR complexed with the two-benzamidinium derivatives studied herein. The MD simulations also confirmed the preferred conformations for these inhibitors obtained by QM/MM based X-ray refinement.

Our observations on benzamidinium are important on another more qualitative level. In SBDD studies refined X-ray structures are relied on to suggest ways in which to modify or build new inhibitor structures. This effort depends critically on accurate protein-ligand structures in order to guide the design process. The PNT case (QacR-Pentadiamidine complex) illustrates clearly what can go awry. The MM refined and PDB structures (see Figure 5a and b) both predict that the two benzamidiniums are planar, while the QM/MM refined structures (see Figures 6) are both twisted out of plane (site 1 and 2). Indeed, these small differences in the computed structures might lead to different conclusions in what molecules to make next. Improved force fields can allay this issue, but given the creativity of modern organic chemistry with respect to the molecular scaffolds one can create this is an ongoing and challenging problem that QM based methods just do not particularly suffer from. Thus, it is safe to conclude that the QM/MM approach is significantly more general than any MM approach.

In this work we have focused on one class of small molecules (benzamidinium derivatives), but there are numerous other examples of classes of drug-like molecules that can be examined. Given the large number of crystal structures of pharmaceutically relevant protein-ligand complexes that are available a comprehensive study of systems with available structure factors using the QM/MM refinement approach could yield interesting insights into preferred conformational preferences. We are in the process of attacking several other classes of molecules along the lines described herein.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Shaoliang Zheng at SUNY-Buffalo for valuable discussion in the torsion motif preferences of small crystal structures from CSD. We thank the NIH for supporting this research via NIH grants GM044974 and GM066859.

References

- 1.David G, Brown MMF. Structure-based drug discovery. 2006;32:32–53. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlichting I. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2000;33:532–538. doi: 10.1021/ar9900459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moffat K. Chemical Review. 2001;101:1569–1582. doi: 10.1021/cr990039q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moffat K. Nature Structural Biology. 1998;5:641–643. doi: 10.1038/1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moffat K. Acta Crystallographica Section A. 1998;54:833–841. doi: 10.1107/s0108767398010605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marius Schmidt HI, Reinhard Pahl Vukiica Srajer. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2005;305:115–154. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-912-5:115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory A, Petsko DR. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2000;4:89–94. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicklaus MC, Wang SM, Driscoll JS, Milne GWA. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 1995;3:411–428. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(95)00031-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mooij WTM, Hartshorn MJ, Tickle IJ, Sharff AJ, Verdonk ML, Jhoti H. Chemmedchem. 2006;1:827–838. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bostrom J, Norrby PO, Liljefors T. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 1998;12:383–396. doi: 10.1023/a:1008007507641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tirado-Rives J, Jorgensen WL. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;49:5880–5884. doi: 10.1021/jm060763i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jack A, Levitt M. Acta Crystallographica Section A. 1978;34:931–935. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tronrud DE, Teneyck LF, Matthews BW. Acta Crystallographica Section A. 1987;43:489–501. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grootenhuis PDJ, Vanboeckel CAA, Haasnoot CAG. Trends in Biotechnology. 1994;12:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perola E, Charifson PS. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2004;47:2499–2510. doi: 10.1021/jm030563w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benfield AP, Teresk MG, Plake HR, DeLorbe JE, Millspaugh LE, Martin SF. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:6830–6835. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang CE, Chen W, Gilson MK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1534–1539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610494104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houk KN, Leach AG, Kim SP, Zhang X. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:4872–4897. doi: 10.1002/anie.200200565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan AR, Parrish JC, Fraser ME, Smith WW, Bartlett PA, James MN. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16839–16845. doi: 10.1021/bi9821364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen FH, Motherwell WDS. Acta Crystallographica Section B-Structural Science. 2002;58:407–422. doi: 10.1107/s0108768102004895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen FH. Acta Crystallographica Section B-Structural Science. 2002;58:380–388. doi: 10.1107/s0108768102003890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berman HM, et al. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 2002;58:899–907. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902003451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernstein FC, Koetzle TF, Williams GJB, Meyer EF, Brice MD, Rodgers JR, Kennard O, Shimanouchi T, Tasumi M. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1977;80:319–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor R. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 2002;58:879–888. doi: 10.1107/s090744490200358x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conklin D, Fortier S, Glasgow JI, Allen FH. Acta Crystallographica Section B-Structural Science. 1996;52:535–549. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen FH, Harris SE, Taylor R. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 1996;10:247–254. doi: 10.1007/BF00355046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohm HJ, Brode S, Hesse U, Klebe G. Chemistry-a European Journal. 1996;2:1509–1513. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bohm HJ, Klebe G. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition in English. 1996;35:2589–2614. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harding MM. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 1999;55:1432–1443. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999007374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanrikulu Y, Schneider G. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:667–677. doi: 10.1038/nrd2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tropsha A, Golbraikh A. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:3494–3504. doi: 10.2174/138161207782794257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vagin AA, Steiner RA, Lebedev AA, Potterton L, McNicholas S, Long F, Murshudov GN. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 2004;60:2184–2195. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallographica Section A. 2008;64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nissink JWM, Murray C, Hartshorn M, Verdonk ML, Cole JC, Taylor R. Proteins-Structure Function and Genetics. 2002;49:457–471. doi: 10.1002/prot.10232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hauptmann J, Sturzebecher J. Thromb Res. 1999;93:203–241. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(98)00192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grzesiak A, Helland R, Smalas AO, Krowarsch D, Dadlez M, Otlewski J. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dullweber F, Stubbs MT, Musil D, Sturzebecher J, Klebe G. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001;313:593–614. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guvench O, Price DJ, Brooks CL. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2005;58:407–417. doi: 10.1002/prot.20326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ota N, Stroupe C, Ferreira-da-Silva JMS, Shah SA, Mares-Guia M, Brunger AT. Proteins-Structure Function and Genetics. 1999;37:641–653. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19991201)37:4<641::aid-prot14>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radmer RJ, Kollman PA. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 1998;12:215–227. doi: 10.1023/a:1007905722422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tominey AF, Docherty PH, Rosair GM, Quenardelle R, Kraft A. Organic Letters. 2006;8:1279–1282. doi: 10.1021/ol053072+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alig L, Edenhofer A, Hadvary P, Hurzeler M, Knopp D, Muller M, Steiner B, Trzeciak A, Weller T. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1992;35:4393–4407. doi: 10.1021/jm00101a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adler M, Davey DD, Phillips GB, Kim SH, Jancarik J, Rumennik G, Light DR, Whitlow M. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12534–12542. doi: 10.1021/bi001477q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murray DS, Schumacher MA, Brennan RG. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:14365–14371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313870200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fokkens J, Klebe G. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2006;45:985–989. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Case DA, et al. San Francisco: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao He KA, Ed Brothers, Kenneth M. Gainesville: Merz; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Engh RA, Huber R. Acta Crystallographica Section A. 1991;47:392–400. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kleywegt GJ, Jones TA. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 1998;54:1119–1131. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998007100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallographica Section A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brooks BE, Piro KM, Brennan RG. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:8389–8395. doi: 10.1021/ja072576v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frisch MJ, et al. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, Simmerling C. Proteins. 2006;65:712–725. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang J, Wolf RM, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA, Case DA. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang W, Cieplak P, Kollman PA. J. Comput. Chem. 2000;21:1049–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura J, Impey RW, Klein ML. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berendsen HJC, Potsma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, DiNola AD, Haak JR. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Renatus M, Bode W, Huber R, Sturzebecher J, Prasa D, Fischer S, Kohnert U, Stubbs MT. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:21713–21719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rauh D, Klebe G, Stubbs MT. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004;335:1325–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Olivero AG, et al. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:9160–9169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zheng S. Private Communication. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cui Q, Elstner M, Kaxiras E, Frauenheim T, Karplus M. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2001;105:569–585. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Monard G, Merz KM., Jr Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:904–911. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ma S, Devi-Kesavan LS, Gao J. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13633–13645. doi: 10.1021/ja074222+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao JL, Truhlar DG. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 2002;53:467–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.53.091301.150114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ryde U. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2003;7:136–142. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Talbi H, Monard G, Loos M, Billaud D. Synthetic Metals. 1999;101:115–116. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maseras F, Lledos A, Clot E, Eisenstein O. Chemical Reviews. 2000;100:601–636. doi: 10.1021/cr980397d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ryde U. Dalton Transactions. 2007:607–625. doi: 10.1039/b614448a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ryde U, Hsiao YW, Rulisek L, Solomon EI. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:726–727. doi: 10.1021/ja062954g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Soderhjelm P, Ryde U. Journal of Molecular Structure-Theochem. 2006;770:199–219. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rulisek L, Ryde U. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2006;110:11511–11518. doi: 10.1021/jp057295t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nilsson K, Hersleth HP, Rod TH, Andersson KK, Ryde U. Biophysical Journal. 2004;87:3437–3447. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.041590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nilsson K, Ryde U. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2004;98:1539–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ryde U, Nilsson K. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:14232–14233. doi: 10.1021/ja0365328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Raha K, Peters MB, Wang B, Yu N, WollaCott AM, Westerhoff LM, Merz KM. Drug Discovery Today. 2007;12:725–731. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cui GL, Li X, Merz KM. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1303–1311. doi: 10.1021/bi062076z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yu N, Li X, Cui GL, Hayik SA, Merz KM. Protein Science. 2006;15:2773–2784. doi: 10.1110/ps.062343206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yu N, Hayik SA, Wang B, Liao N, Reynolds CH, Merz KM. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2006;2:1057–1069. doi: 10.1021/ct0600060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schumacher MA, Miller MC, Grkovic S, Brown MH, Skurray RA, Brennan RG. Science. 2001;294:2158–2163. doi: 10.1126/science.1066020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grkovic S, Brown MH, Schumacher MA, Brennan RG, Skurray RA. Journal of Bacteriology. 2001;183:7102–7109. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7102-7109.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.MacKerell AD, et al. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.