Abstract

A growing body of evidence suggests that glutamatergic systems may be involved in the pathophysiology of major depression and the mechanism of action of antidepressants. We investigated the effects of amitriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, on the activity of excitatory amino acid transporter type 3 (EAAT3), proteins that can regulate extracellular glutamate concentrations in the brain. EAAT3 was expressed in the Xenopus oocytes. Using two-electrode voltage clamp, membrane currents were recorded after application of 30 µM L-glutamate in the presence or absence of various concentrations of amitriptyline or after application of various concentrations of L-glutamate in the presence or absence of 0.64 µM amitriptyline. Amitriptyline concentration-dependently reduced EAAT3 activity. This inhibition reached statistical significance at 0.38 – 1.27 µM amitriptyline. Amitriptyline at 0.64 µM reduced the Vmax, but did not affect the Km, of EAAT3 for L-glutamate. The amitriptyline inhibition disappeared after a 4-min washout. Phorbol-12-myrisate-13-acetate, a protein kinase C activator, increased EAAT3 activity. However, 0.64 µM amitriptyline induced a similar degree of decrease in EAAT3 activity in the presence or absence of phorbol-12-myrisate-13-acetate. Our results suggest that amitriptyline at clinically relevant concentrations reversibly reduces EAAT3 activity via decreasing its maximal velocity of glutamate transporting function. The effects of amitriptyline on EAAT3 activity may represent a novel site of action for amitriptyline to increase glutamatergic neurotransmission. Protein kinase C may not be involved in the effects of amitriptyline on EAAT3.

Keywords: Amitriptyline, glutamate, glutamate transporters, protein kinase C

Introduction

Glutamate is the principal excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (Fonnum 1984). Glutamate transporters (also called excitatory amino acid transporters, EAAT) regulate glutamate concentrations in the synaptic cleft by transporting glutamate from extracellular space to intracellular compartments under physiological conditions, which can prevent extracellular glutamate accumulation and regulate glutamatergic neurotransmission (Kanai & Hediger 1992; Kanai et al 1993; Danbolt 2001). Alterations in EAAT functions have been suggested to play a role in several acute and chronic nervous system diseases, such as psychosis, epilepsy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Rothstein et al 1992; Torp et al 1997). Five EAATs have been identified: EAAT 1–5 (Danbolt 2001). The transporting functions of all five EAATs are Na+-dependent. They use the trans-membrane gradient of Na+, K+ and H+ as driving force to uptake glutamate(Billups et al 1998; Danbolt 2001).

A growing body of evidence from preclinical and clinical research suggests that brain glutamatergic systems may be involved in the pathophysiology of major depression and the mechanism of action of antidepressants (Cai & McCaslin 1992; Duman et al 1999; Auer et al 2000; Palucha & Pilc 2005; Pittenger et al 2007). Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are commonly used drugs for major depressive disorders and are also widely used in chronic pain states, such as neuropathic and inflammatory pain (Eisenach & Gebhart 1995; McQuay et al 1996; Abdel-Salam et al 2003). These TCA effects have been thought to be mediated mainly by inhibition of monoamine reuptake. However, recent studies suggest the involvement of glutamatergic system in the action of these drugs (Cai & McCaslin 1992; Golembiowska & Dziubina 2001; Andin et al 2004). Amitriptyline, a commonly used TCA, has been shown to regulate the mRNA expression of EAAT3, the major neuronal EAATs (Andin et al 2004), in rat brain. However, it is not known yet whether TCA can affect EAAT activity. Thus, we designed this study to determine the effects of amitriptyline on EAAT3 activity by using the Xenopus oocyte expression system.

Materials and Methods

The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, VA, USA). The recommendations from the Declaration of Helsinki and the internationally accepted principles in the care and use of experimental animals had been adhered to during the study. Mature female Xenopus laevis frogs were purchased from Xenopus I (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). All reagents, unless specified below, were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Oocyte preparation and injection

As described before (Do et al 2002), frogs were anesthetized in 500 ml of 0.2% 3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester in water until unresponsive to painful stimuli (toe pinching) and underwent surgery on ice. Oocytes were surgically retrieved and placed immediately in modified Barth’s solution containing 88 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 2.4 mM NaHCO3, 0.41 mM CaCl2, 0.82 mM MgSO4, 0.3 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.1 mM gentamicin and 15 mM HEPES with pH adjusted to 7.5. The oocytes were defolliculated with gentle shaking for approximately 2 h in calcium-free OR-2 solution containing 82.5 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 4 mM HEPES and 0.1% collagenase type Ia with pH adjusted to 7.5 and then incubated in modified Barth’s solution that does not contain collagenase at 16°C for 1 day before the injection of EAAT3 mRNA.

The rat EAAT3 complementary DNA (cDNA) construct was provided by Dr. M.A. Hediger (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Institutes of Medicine, Boston, MA). The cDNA was subcloned in a commercial vector (BluescriptS Km). The plasmid DNA was linearized with a restriction enzyme (NotI) and mRNA was synthesized in vitro with a commercially available kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). The resulting mRNA was quantified spectrophotometrically and diluted in sterile water. This mRNA was used for the cytoplasmic injection of oocytes in a concentration of 40 ng/40 nl by using an automated microinjector (Nanoject; Drummond Scientific Co., Broomall, PA). Oocytes were then incubated at 16°C in modified Barth’s solution for 3 days before voltage-clamping experiments.

Electrophysiological recordings

Experiments were performed at room temperature (approximately 21°C – 23°C). A single oocyte was placed in a recording chamber that was < 1 ml in volume and was perfused with 4 ml/min Tyrode’s solution containing 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 10 mM dextrose and 10 mM HEPES with pH adjusted to 7.5. Clamping microelectrodes were pulled from capillary glass (10 µl Drummond Microdispenser, Drummond Scientific) on a micropipette puller (model 700C; David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Tips were broken at a diameter of approximately 10 µm and filled with 3 M KCl obtaining resistance of 1–3 MΩ. Oocytes were voltage-clamped using a two-electrode voltage clamp amplifier (OC725-A; Warner Corporation, New Haven, CT) that was connected to a data acquisition and analysis system running on a personal computer. The acquisition system consisted of a DAS-8A/D conversion board (Keithley-Metrabyte, Taunton, MA). Analyses were performed with pCLAMP7 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). All measurements were performed at a holding potential of −70 mV. Oocytes that did not show a stable holding current less than 1 µA were excluded from analysis. L-Glutamate was diluted in Tyrode’s solution and superfused over the oocyte for 25 s (5 ml/min). L-Glutamate-induced inward currents were sampled at 125 Hz for 1 min: 5 s of baseline, 25 s of L-glutamate application and 30 s of washing with Tyrode’s solution. The glutamate-induced peak currents were calculated to reflect the amount of glutamate transported. We used 30 µM L-glutamate, unless indicated otherwise, in this study because the Km of EAAT3 for L-glutamate was shown to be 27 – 30 µM in previous studies (Do et al 2002; Kim et al 2003).

Administration of experimental chemicals

Amitriptyline was dissolved in methanol (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA) and then diluted by Tyrode’s solution to the appropriate final concentrations (10 ng/ml, 60 ng/ml, 120 ng/ml, 200 ng/ml, 280 ng/ml or 400 ng/ml that corresponds to 0.032 µM, 0.19 µM, 0.38 µM, 0.64 µM, 0.89 µM or 1.27 µM, respectively). In the control experiments, oocytes were perfused with Tyrode’s solution for 4 min before the application of Tyrode’s solution containing L-glutamate for the electrophysiological recording. In the amitriptyline-treated group, oocytes were perfused with Tyrode’s solution for the first minute for stabilization followed by Tyrode’s solution containing amitriptyline for 3 min before the application of Tyrode’s solution containing L-glutamate for the electrophysiological recording. To determine the reversibility of amitriptyline effects, the responses to L-glutamate were assayed, oocytes were then treated with 0.64 µM amitriptyline and the responses to L-glutamate were recorded again. Subsequently, oocytes were perfused with Tyrode’s solution for 4 min and the responses to L-glutamate were measured for the third time. To study the effects of protein kinase C (PKC) activation on amitriptyline-induced change of EAAT3 activity, oocytes were pre-incubated with 100 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), a PKC activator, for 10 min just before the application of 0.64 µM amitriptyline.

Data analysis

Responses are reported as mean ± S.D. Each experimental condition was performed with oocytes from at least three different frogs. Since the expression level of transporter proteins in oocytes of different batches may vary, variability in response among batches of oocytes is common. Thus, responses were normalized to the mean values of the same-day controls for each batch. Similarly, in the reversibility experiments, responses were normalized to the responses of the same oocytes to 1 mM glutamate under control conditions (before the amitriptyline treatment). This concentration of glutamate was the highest concentration used to induce EAAT3 activity and this normalization allowed us to pool together data from different batches of oocytes for analysis. Statistical analysis was performed by one way repeated measures ANOVA (for the reversibility study) or one way ANOVA (for all other experiments) followed by the Tukey multiple comparison test. A P < 0.05 was accepted as significant.

Results

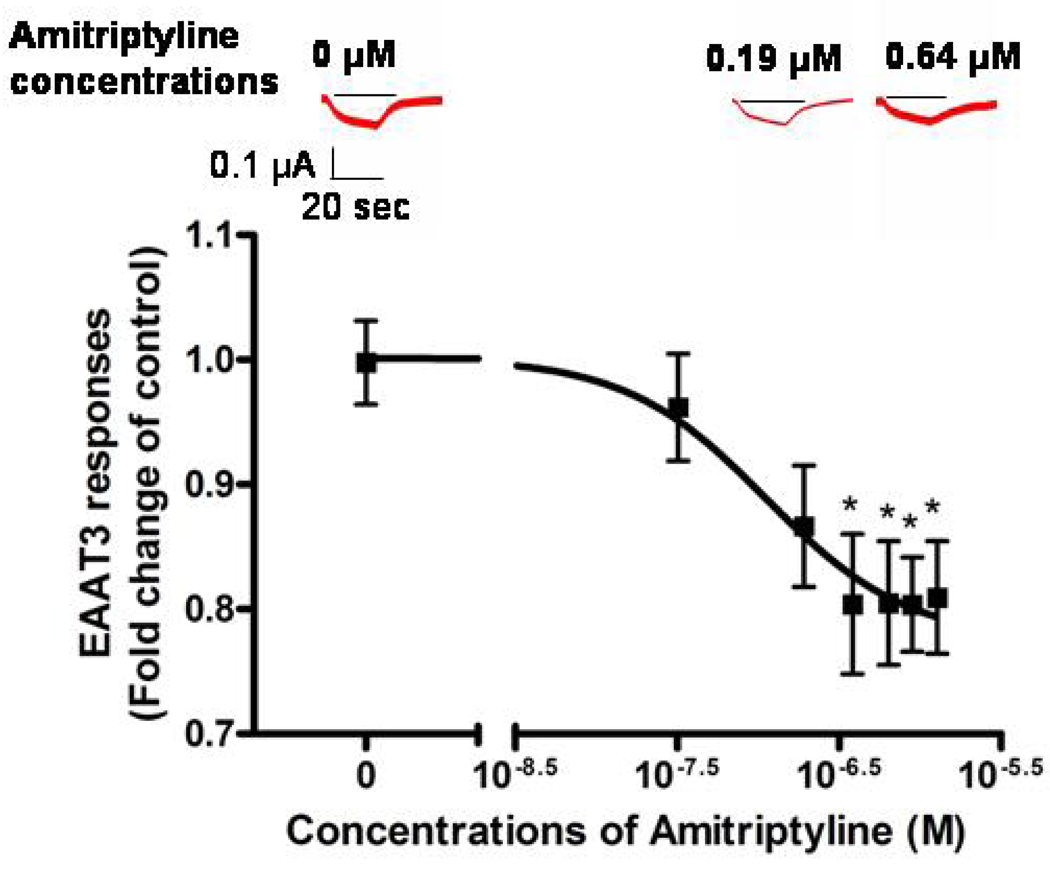

L-Glutamate (30 µM) induced no current in the oocytes without injection of EAAT3 mRNA (data not shown) and an inward current in oocytes injected with EAAT3 mRNA (Fig. 1). Our previous studies showed that this current was mediated via EAAT3 (Do et al 2002; Kim et al 2003). The glutamate-induced current in oocytes expressing EAAT3 was not affected by 0.04% (v/v) methanol, the solvent for amitriptyline (0.92 ± 0.48-folds of control, n = 11, P > 0.05). This concentration of methanol was the highest concentration expected in the Tyrode’s solution containing amitriptyline. While amitriptyline alone did not induce any currents in oocytes injected with or without EAAT3 mRNA (data not shown), amitriptyline concentration-dependently reduced EAAT3 responses with an IC50 value of 0.11 µM (Fig. 1). Since the inhibition reached maximal at concentrations higher than 0.38 µM, we used 0.64 µM for further experiments. The EAAT3 response to L-glutamate in the presence of 0.64 µM amitriptyline was reduced by ~20% (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Dose-response of amitriptyline inhibition of EAAT3 responses to 30 µM L-glutamate.

The IC50 value for this inhibition was 0.11 µM. Three typical current traces are inserted in the figure. The short line above each current trace represents the time of L-glutamate application. Data are means ± S.D. (n = 27 – 48 in each data point). * P < 0.05 compared to control.

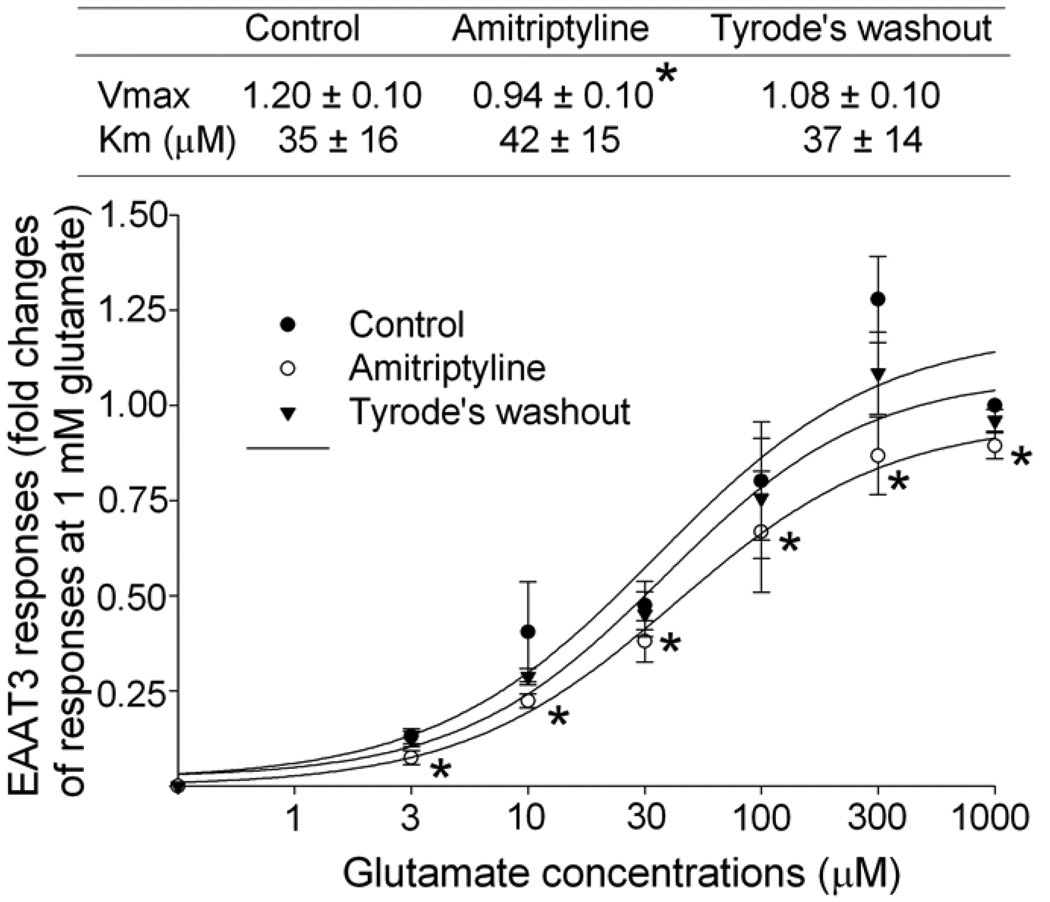

Consistent with our previous studies (Do et al 2002; Kim et al 2003), the Km of EAAT3 for L-glutamate was 35 ± 16 µM. This Km was not significantly affected by 0.64 µM amitriptyline. However, amitriptyline significantly decreased the Vmax of EAAT3 for L-glutamate (from 1.20 ± 0.10 of control group to 0.94 ± 0.10 of amitriptyline group, P < 0.05). This amitriptyline effect disappeared in occytes perfused with Tyrode’s solution for 4 min after amitriptyline treatment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Effects of amitriptyline on EAAT3 activity.

The EAAT3 responses to various L-glutamate concentrations were measured before (control group) and immediately after amitriptyline treatment (amitriptyline group) and after a 4-min Tyrode’s perfusion (Tyrode’s washout). The Vmax and Km values of EAAT3 response to L-glutamate are listed in the table above the figure. Data are means ± S.D. (n = 6 in each data point). * P < 0.05 compared to the corresponding values in control group.

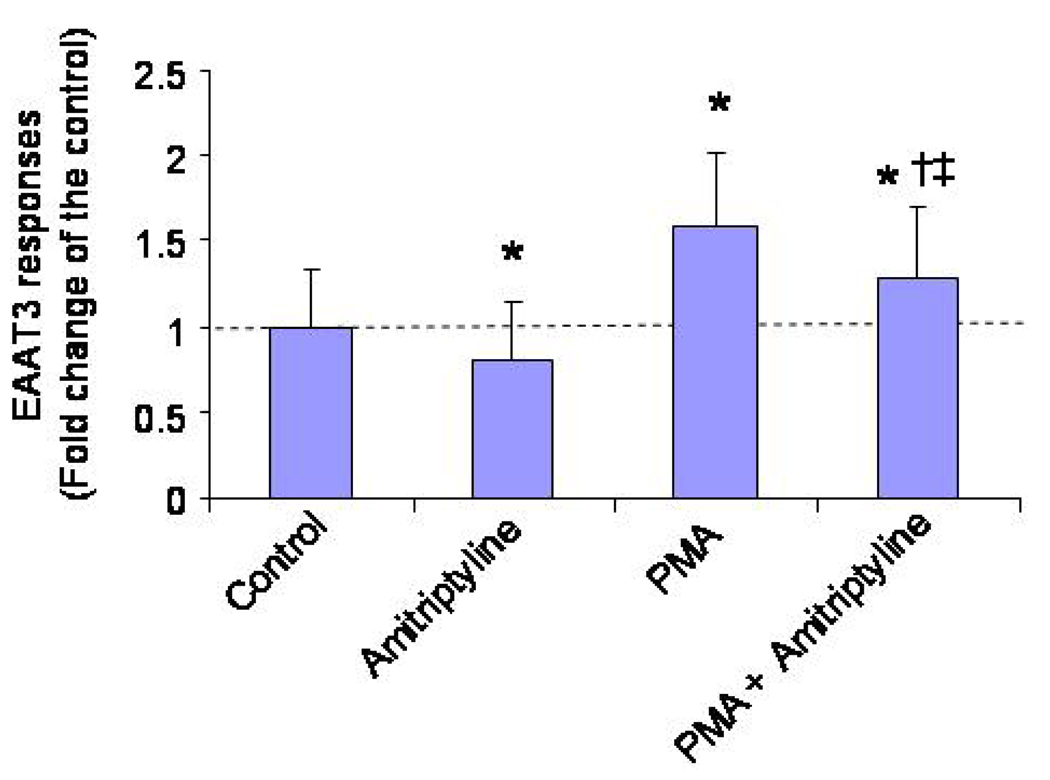

Preincubation of the oocytes with 100 nM PMA, a PKC activator, increased EAAT3 activity significantly compared to the control (Fig. 3). However, 0.64 µM amitriptyline caused a similar degree of decrease in EAAT3 responses no matter whether PMA was present or not (EAAT3 responses in the amitriptyline groups were 0.84 ± 0.32 and 0.78 ± 0.34 fold of the corresponding controls, respectively, in the presence or absence of PMA, n = 24 – 45 , P > 0.05).

Fig. 3. Effects of protein kinase C (PKC) activation on EAAT3 activity in the presence or absence of 0.64 µM amitriptyline.

Oocytes were exposed to or were not exposed to 100 nM phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA, a PKC activator) for 10 min before they were stimulated by 30 µM L-glutamate in the presence or absence of amitriptyline. Data are means ± S.D. (n = 24 – 45 in each data point). * P < 0.05 compared to control, † P < 0.05 compared to PMA alone, ‡ P < 0.05 compared to amitriptyline alone.

Discussion

Antidepressants have been used for decades and their therapeutic effects have been thought to be mediated by inhibition of monoamine uptake. However, antidepressant-like activity can be produced not only by drugs modulating the glutamatergic synapses, but also by agents that affect subcellular signaling systems linked to excitatory amino acid receptors (Paul & Skolnick 2003). Since EAATs can regulate extracellular glutamate concentrations and glutamatergic neurotransmission (Danbolt 2001), EAATs may be a target for antidepressants. Consistent with this idea, it has been shown that amitriptyline regulates EAAT3 mRNA expression in rat brain (Andin et al 2004). Amitriptyline also blocks morphine-induced redistribution of EAAT1 and EAAT2, but not EAAT3, from the plasma membrane to intracellular space in rat spinal cord and such effects have been considered to play a role in the reduction of morphine tolerance by amitriptyline (Tai et al 2007).

Our results showed that amitriptyline concentration-dependently reduced EAAT3 activity with an IC50 value of 0.11 µM. This inhibition was statistically significant at concentrations higher than 0.38 µM. The exact amitriptyline concentrations around EAAT3 in the brains of patients on therapeutic doses of amitriptyline are not known. However, therapeutic range of plasma concentrations of amitriptyline for depression is 0.3 – 0.8 µM (1995). The concentration ratio of amitriptyline in the cerebral spinal fluid vs. blood in human is ~0.3 (Engelhart & Jenkins 2007). Thus, therapeutic range of amitriptyline concentrations in the cerebral spinal fluid may fall into the effective concentrations that can inhibit EAAT3 activity. In addition, it has been estimated that the amitriptyline concentrations in the brains of patients on therapeutic doses is about 1 to 10 µM (Glotzbach & Preskorn 1982), concentrations that are high enough to maximize the inhibitory effects of amitriptyline on EAAT3 activity as shown in our study. Thus, our results suggest that amitriptyline at clinically relevant concentrations can inhibit EAAT3 activity.

Our results also show that amitriptyline reduced the Vmax, but did not affect the Km, of EAAT3 for L-glutamate, suggesting that amitriptyline does not affect the affinity of EAAT3 for L-glutamate but decrease the total EAAT3 available for glutamate transporting. Interestingly, the amitriptyline-decreased EAAT3 activity recovered after a short washout, indicating that the amitriptyline effect was reversible. It has been proposed that amitriptyline, by inhibiting the uptake of monoamines, can increase serotonin in the synaptic cleft, which can then activate the glutamatergic synapses and increase the amount of glutamate in the synaptic cleft (Hasuo et al 2002). Our results suggest that direct inhibition of EAAT activity may be another mechanism for amitriptyline to increase glutamate concentrations in the synapses. Since reduced glutamate levels are seen in anterior cingulated cortex of depressed patients (Auer et al 2000), the inhibition of EAAT activity by amitriptyline may contribute to its anti-depressant effects.

It has been shown that the loss of EAAT3 produces mild neurotoxicity and induces epilepsy (Rothstein et al 1996). Therefore, inhibition of EAAT3 activity by amitriptyline may cause neurotoxicity. However, this effect may not occur because of three reasons. First, EAATs other than EAAT3 may partially compensate the function of EAAT3. Second, the maximal inhibition of EAAT3 activity by amitriptyline was ~20% and this ceiling effect may safeguard the degree of glutamate increase in the synaptic cleft. Third, amitriptyline has been shown to block NMDA-induced toxicity, although the ED50 for this protection was ~7 µM (McCaslin et al 1992) that is higher than the concentrations needed to inhibit EAAT3 activity in this study.

Multiple studies have shown that PKC activation can increase EAAT3 activity (Do et al 2002; Huang & Zuo 2005; Huang et al 2006) and amitriptyline can inhibit PKC (Tai et al 2007). Thus, it is possible that the amitriptyline effects on EAAT3 activity may be mediated by PKC. Our results showed that the degree of EAAT3 activity inhibition caused by amitriptyline at 0.64 µM, a concentration that has maximized its effects on EAAT3 activity, was not affected by PMA. These results suggest that the amitriptyline-induced reduction of EAAT3 activity is not mediated by PKC. Consistent with this idea, our previous studies suggest that PKC may not play an important role in regulating the basal EAAT3 activity because PKC inhibition does not affect the basal EAAT3 activity (Do et al 2002; Huang & Zuo 2005).

EAATs use the trans-membrane gradient of Na+, K+ and H+ as driving force to uptake glutamate(Billups et al 1998; Danbolt 2001). Drugs may affect the gradients of these ions to change EAAT activity. It is known that amitriptyline can block sodium channels (Dick et al 2007). This effect will hyperpolarize the cell membrane and can increase the trans-membrane gradients of sodium. Consequently, the EAAT3 activity would be expected to increase. This expectation is in contrast to our results. Thus, the effects of amitriptyline on sodium channels may not contribute to the inhibition of EAAT3 activity caused by amitriptyline.

Conclusion

Amitriptyline, a TCA, dose-dependently inhibits EAAT3 activity via reducing the Vmax of EAAT3 response to L-glutamate. This effect represents a novel site of action for amitriptyline to increase the glutamatergic neurotransmission. PKC may not be involved in this amitriptyline effect.

Footnotes

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM065211 and RO1 NS045983 (to Z. Zuo), Bethesda, MD, USA.

References

- Abdel-Salam OM, Nofal SM, El-Shenawy SM. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive effects of different antidepressants in the rat. Pharmacol Res. 2003;48:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andin J, Stenfors C, Ross SB, Marcusson J. Modulation of neuronal glutamate transporter rEAAC1 mRNA expression in rat brain by amitriptyline. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;126:74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer DP, Putz B, Kraft E, Lipinski B, Schill J, Holsboer F. Reduced glutamate in the anterior cingulate cortex in depression: an in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:305–313. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldessarini RJ. Drugs and the treatment of psychiatric disorders: Depression and mania. In: Hardman JG, Goodman GA, Limbird LE, editors. Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York: McGraw Hill; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Billups B, Rossi D, Oshima T, Warr O, Takahashi M, Sarantis M, Szatkowski M, Attwell D. Physiological and pathological operation of glutamate transporters. Progress in Brain Research. 1998;116:45–57. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)60429-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, McCaslin PP. Amitriptyline, desipramine, cyproheptadine and carbamazepine, in concentrations used therapeutically, reduce kainate- and N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced intracellular Ca2+ levels in neuronal culture. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;219:53–57. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90579-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt NC. Glutamate uptake. Progress in Neurobiology. 2001;65:1–105. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick IE, Brochu RM, Purohit Y, Kaczorowski GJ, Martin WJ, Priest BT. Sodium channel blockade may contribute to the analgesic efficacy of antidepressants. J Pain. 2007;8:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do S-H, Kamatchi GL, Washington JM, Zuo Z. Effects of volatile anesthetics on glutamate transporter, excitatory amino acid transporter type 3. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1492–1497. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200206000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Malberg J, Thome J. Neural plasticity to stress and antidepressant treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1181–1191. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenach JC, Gebhart GF. Intrathecal amitriptyline acts as an N-methyl-Daspartate receptor antagonist in the presence of inflammatory hyperalgesia in rats. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:1046–1054. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199511000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhart DA, Jenkins AJ. Comparison of drug concentrations in postmortem cerebrospinal fluid and blood specimens. J Anal Toxicol. 2007;31:581–587. doi: 10.1093/jat/31.9.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonnum F. Glutamate: a neurotransmitter in mammalian brain. J Neurochem. 1984;42:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb09689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzbach RK, Preskorn SH. Brain concentrations of tricyclic antidepressants: single-dose kinetics and relationship to plasma concentrations in chronically dosed rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1982;78:25–27. doi: 10.1007/BF00470582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golembiowska K, Dziubina A. Involvement of adenosine in the effect of antidepressants on glutamate and aspartate release in the rat prefrontal cortex. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;363:663–670. doi: 10.1007/s002100100421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasuo H, Matsuoka T, Akasu T. Activation of presynaptic 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptors facilitates excitatory synaptic transmission via protein kinase C in the dorsolateral septal nucleus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7509–7517. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07509.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Zuo Z. Isoflurane induces a protein kinase C alpha-dependent increase in cell surface protein level and activity of glutamate transporter type 3. Molecular Pharmacology. 2005;67:1522–1533. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.007443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Feng X, Sando JJ, Zuo Z. Critical Role of Serine 465 in Isoflurane-induced Increase of Cell-surface Redistribution and Activity of Glutamate Transporter Type 3. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38133–38138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai Y, Hediger MA. Primary structure and functional characterization of a high-affinity glutamate transporter. Nature. 1992;360:467–471. doi: 10.1038/360467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai Y, Smith CP, Hediger MA. A new family of neurotransmitter transporters: the high-affinity glutamate transporters. Faseb J. 1993;7:1450–1459. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.15.7903261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Lim YJ, Ro YJ, Min SW, Kim CS, Do SH, Kim YL, Zuo Z. Effects of ethanol on the rat glutamate excitatory amino acid transporter type 3 expressed in Xenopus oocytes: role of protein kinase C and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1548–1553. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000092061.92393.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaslin PP, Yu XZ, Ho IK, Smith TG. Amitriptyline prevents N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-induced toxicity, does not prevent NMDA-induced elevations of extracellular glutamate, but augments kainate-induced elevations of glutamate. J Neurochem. 1992;59:401–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuay HJ, Tramer M, Nye BA, Carroll D, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA. A systematic review of antidepressants in neuropathic pain. Pain. 1996;68:217–227. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palucha A, Pilc A. The involvement of glutamate in the pathophysiology of depression. Drug News Perspect. 2005;18:262–268. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2005.18.4.908661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul IA, Skolnick P. Glutamate and depression: clinical and preclinical studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:250–272. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger C, Sanacora G, Krystal JH. The NMDA receptor as a therapeutic target in major depressive disorder. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2007;6:101–115. doi: 10.2174/187152707780363267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Martin LJ, Kuncl RW. Decreased glutamate transport by the brain and spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [see comments] New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326:1464–1468. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199205283262204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Dykes-Hoberg M, Pardo CA, Bristol LA, Jin L, Kuncl RW, Kanai Y, Hediger MA, Wang Y, Schielke JP, Welty DF. Knockout of glutamate transporters reveals a major role for astroglial transport in excitotoxicity and clearance of glutamate. Neuron. 1996;16:675–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai YH, Wang YH, Tsai RY, Wang JJ, Tao PL, Liu TM, Wang YC, Wong CS. Amitriptyline preserves morphine's antinociceptive effect by regulating the glutamate transporter GLAST and GLT-1 trafficking and excitatory amino acids concentration in morphine-tolerant rats. Pain. 2007;129:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torp R, Hoover F, Danbolt NC, Storm-Mathisen J, Ottersen OP. Differential distribution of the glutamate transporters GLT1 and rEAAC1 in rat cerebral cortex and thalamus: an in situ hybridization analysis. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1997;195:317–326. doi: 10.1007/s004290050051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]