Abstract

A novel methodology for the automated de novo identification of peptides via integer linear optimization (also referred to as integer linear programming or ILP) and tandem mass spectrometry is presented in this article. The various features of the mathematical model are presented and examples are used to illustrate the key concepts of the proposed approach. A variety of challenging peptide identification problems, accompanied by a comparative study with five state-of-the-art methods, are examined to illustrate the proposed method’s ability to address (a) residue-dependent fragmentation properties that result in missing ion peaks and (b) the variability of resolution in different mass analyzers. A preprocessing algorithm is utilized to identify important m/z values in the tandem mass spectrum. Missing peaks, due to residue-dependent fragmentation characteristics, are dealt with using a two-stage algorithmic framework. A cross-correlation approach is used to resolve missing amino acid assignments and to select the most probable peptide by comparing the theoretical spectra of the candidate sequences that were generated from the ILP sequencing stages with the experimental tandem mass spectrum. The novel, proposed de novo method, denoted as PILOT, is compared to existing popular methods such as Lutefisk, PEAKS, PepNovo, EigenMS, and NovoHMM for a set of spectra resulting from QTOF and ion trap instruments.

Of fundamental importance in proteomics is the problem of peptide and protein identification. Over the past couple decades, tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography has emerged as a powerful experimental technique for the effective identification of peptides and proteins. A description of the various experimental frameworks for separation, ionization, and measurement techniques can be found elsewhere.1,2 In recognition of the extensive amount of sequence information embedded in a single mass spectrum, tandem MS has served as an impetus for the recent development of numerous computational approaches formulated to sequence peptides robustly and efficiently with particular emphasis on the integration of these algorithms into a high-throughput computational framework for proteomics. The two most frequently reported computational approaches in the literature are (a) de novo and (b) database search methods, both of which can utilize deterministic, probabilistic, or stochastic solution techniques.

The majority of peptide identification methods used in industry are database search methods3–11 due to their accuracy and their ability to exploit organism information during the identification. An essential component in database methods is a model for scoring the experimental tandem mass spectra against the theoretical spectra of a peptide obtained from a protein database. The main difference between these database methods lies in the type of scoring function utilized to rank-order the most probable peptide matches and the type of sequence database in which the search is conducted. These database types include protein sequence, genomic, or expressed sequence tag.

A variety of techniques for peptide identification using databases currently exist. One approach, as implemented in the SEQUEST algorithm,3–5 uses a signal-processing technique known as cross-correlation to mathematically determine the overlap between a theoretical spectrum as derived from a sequence in the database and the experimental spectrum under investigation. The more frequently used technique, known as probability-based matching, utilizes a probabilistic model to determine whether an ion peak match between the experimental and theoretical tandem mass spectrum is actual or random.6,8,9,11 Various models have been proposed for this purpose, ranging from a likelihood ratio hypothesis test8,11 to the null hypothesis that peptide matches are random.9 Spectral dependencies from empirical observations are often integrated into these models to enhance the predictive capabilities. Despite the sophistication of these database methods, they are ineffective if the database in which the search is conducted does not contain the corresponding peptide responsible for generating the tandem mass spectrum. Furthermore, in some instances, specifying the enzyme used in proteolytic digestion can exclude the correct peptide from the search space. It is important to point out that the variety of scoring functions proposed indicates that the peptide with the best score is not necessarily the peptide responsible for generating the tandem mass spectrum. In light of this, significant efforts have been invested in the development of postdatabase search validation tools.12–17 Several types of algorithms have been proposed for analyzing the results of SEQUEST alone, ranging from statistical models based on linear discriminant analysis14 to probability-based scoring procedures12 to the use of support vector machines for the classification of the scores reported.16

De novo methods have received considerable interest since they are the only efficient means for applications such as finding novel proteins, amino acid mutations, and studying the proteome before the genome. A prominent methodology for the de novo peptide sequencing problem is a spectrum graph approach,18–28 which in many methods is solved using a dynamic programming algorithm.19,21,26,27 Various types of graph representations have been proposed, but the majority of methods map the peaks in the tandem mass spectrum to nodes on a directed graph, where the nodes are connected by edges if the mass difference between them is equal to the weight of an amino acid. The nodes or edges of the spectrum graph are typically assigned scores based on empirically derived weights. An interesting postprocessing technique is employed by the de novo algorithm Lutesfisk,18,22 where a modified version of FASTA (a homology-based database search program) is used to resolve ambiguous or unknown entries due to missing ion peaks and isobaric residues.

Although the spectrum graph approach is found in the majority of de novo algorithms to date, several alternative techniques have also been developed. For example, the de novo algorithm PEAKS29 generates 10 000 potential sequences using a dynamic programming algorithm and then in a subsequent step reevaluates the predicted sequences using a stricter confidence scorer. A divide-and-conquer algorithm was recently proposed in which the tandem mass spectra of the candidate peptide is subsequently predicted using a quantitative kinetic model.30,31 Another technique attacks the peptide identification problem via stochastic optimization using genetic algorithms to solve multiobjective models and can empirically test for independence between scoring functions.32–34 The algorithm NovoHMM35 uses a hidden Markov model to solve the peptide identification problem, where the observable random variables are the observed mass peaks and the hidden variables correspond to the unknown peptide sequence. Despite the vast potential of de novo methods, they can be computationally demanding and may exhibit inconsistent prediction accuracies.

Other approaches include sequence tag-based hybrid methods where a partial sequence internal to the peptide, known as a “sequence tag”, is determined using abundant intensity peaks in the high-mass region of the tandem mass spectra and the remaining portions of the sequence, which span from the ends of sequence tag to the N-terminal and C-terminal of the peptide, are determined via database searching.36–38 This particular approach is advantageous because it combines the strengths from both de novo and database methodologies.

In this paper, a novel integer linear optimization approach is introduced to efficiently address the de novo peptide identification problem so as to form a basis for a high-throughput computational framework for peptide identification. This framework is denoted as PILOT, which stands for Peptide identification via Integer Linear Optimization and Tandem mass spectrometry.

The novelty of this method is that it is the first integer linear optimization (ILP) formulation for the peptide identification problem which allows the following: (1) a rigorous rank-ordered list of optimal candidate sequences via integer cuts, (2) the direct incorporation of complementary ions into the sequencing calculations, and (3) the introduction of error tolerance for the mass of the parent peptide as a variable in the sequencing calculations. Several other traditional de novo methods have to produce thousands of sequences to guarantee that the optimal candidate sequence with respect to a postulated objective function has been reported. Our method rigorously guarantees that the optimal solution has been calculated without having to exhaustively enumerate the space of candidate sequences.

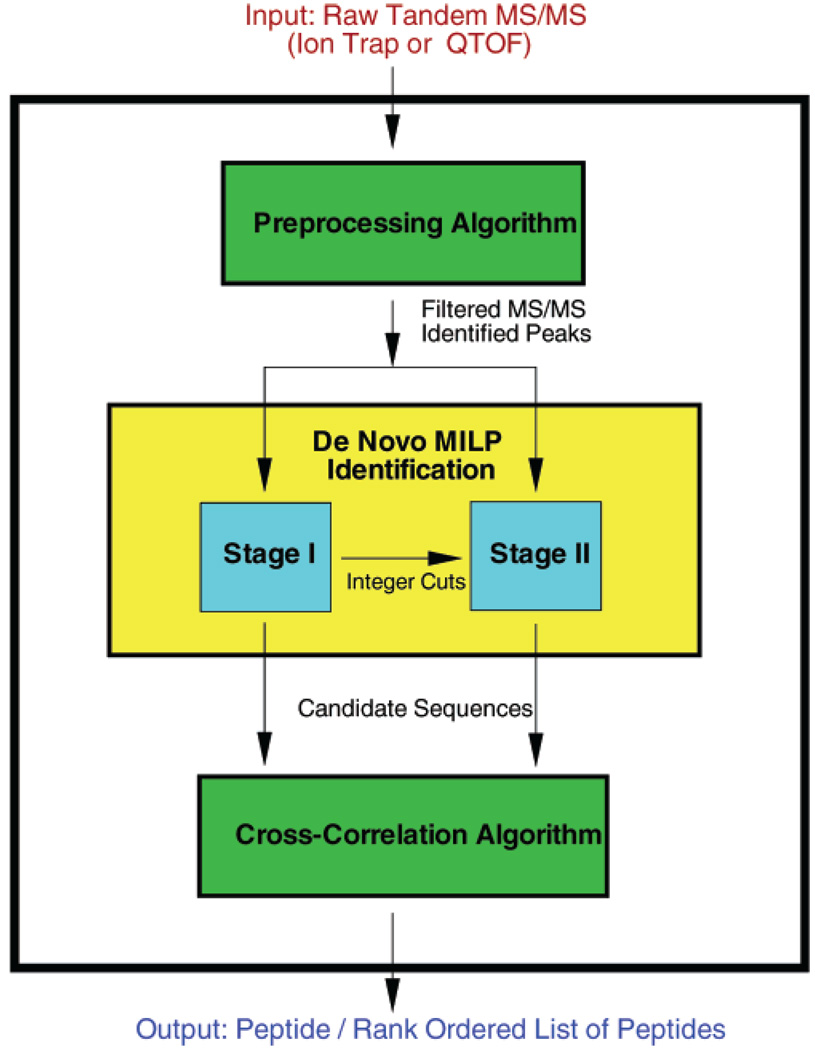

The outline of the article is as follows. Mathematical Model for Peptide Identification provides an outline of the mathematical model employed for the sequencing of peptides via integer linear optimization, addressing the information concerning sets, parameters, variables, boundary conditions, constraints, and the objective function. The framework for the two-stage algorithmic approach is also presented in this section. In Preprocessing of Spectral Data, an overview of the preprocessing algorithm used to identify certain peaks and to validate boundary conditions prior to the formulation of the ILP problem is provided. Postprocessing: Scoring Candidate Sequences discusses a method for selecting the most probable sequence by cross-correlating the theoretical spectra of the candidate sequences with the experimental tandem mass spectrum. A comparative computational study with several existing de novo methods is then presented in the Experimental Section to benchmark the performance of PILOT. The overall framework for PILOT is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall framework for automated peptide identification.

MATHEMATICAL MODEL FOR PEPTIDE IDENTIFICATION

This section provides a thorough description of the mathematical formulation for the de novo identification of peptides of spectra resulting from tandem mass spectrometry. Model Description discusses the essential components of the integer linear programming problem formulation: sets, parameters, binary variables, boundary conditions, constraint equations, and the objective function. A two-stage framework is utilized to address missing peaks in the tandem mass spectrum and is presented in Missing Ion Peaks: Two-Stage Algorithmic Approach.

Model Description

(1) Parameters

The relevant problem parameters correspond to the information provided in a tandem mass spectrum. It is important to note that the mass of the parent peptide and the masses of the ion peaks in the tandem mass spectra are subject to a certain degree of experimental error.19 The parameters are as follows: mP, mass of parent peptide; mass-(ion peak i), mass of ion peak i; λi, intensity of ion peak i.

(2) Sets

The first set to consider is the mass difference between all the peaks in the tandem mass spectrum, which we denote by the matrix M defined in eq 1.

| (1) |

Note that the index i represents the rows and the index j represents the columns of the matrix Mi,j. The sequencing of the peptide should be restricted to only those peaks that differ in mass by the weight of an amino acid. The indices corresponding to these peak pairs are stored in the matrix S, defined in eq 2.

| (2) |

The mass difference between peak i and peak j is equal to the weight of some amino acid for every (i,j) ∈ Si,j. The subsequent problem formulation will only be considered over the set Si,j.

Other sets can be constructed based on known relationships between fragment ions. An important requirement in sequencing a candidate peptide is that it is derived using ions from the same ion series (i.e., b, y, etc.). While it is not known a priori of what ion type a given mass peak is, there do exist important relationships among the different ions. As the charged parent peptide undergoes collision-induced dissociation (CID), it primarily fragments into two ion pairs: either a and x, b and y, or c and z, where all three pairs are what are known as complementary ions by definition. These pairs are easily identified since the sum of two complementary ions is equal to the weight of the parent peptide, mP, as determined experimentally. The indices of peak pairs which satisfy this relationship are stored in the matrix C, defined in eq 3.

| (3) |

This set will be useful for eliminating certain ions in the sequencing calculations. However, one should note that further fragmentation of these ions is possible and frequently observed, which places limitations on how many complementary ions are actually detected in a spectrum.

When discussing the elements of these sets in a conceptual manner, it is best to consider that the index pair (i,j) ∈ S graphically represents a “path” leading from peak i to a peak j of greater mass via the weight of some amino acid. Likewise, a path leaving peak j to some peak k of greater mass by the weight of an amino acid is represented by the element (j,k) ∈ S, with particular emphasis on the ordering of the indices. The combination of the paired elements (i,j) and (j,k) constitute a continuous path through the peak j. This process of constructing a continuous, non-overlapping path between peaks subject to certain constraints is the essence of the peptide sequencing problem. Classifying peak connections using the above sets in conjunction with properly formulated constraints enhances the computational efficiency of the sequencing algorithm by reducing the variable space.

(3) Binary Variables

Binary 0–1 variables are utilized in the problem formulation to model which peaks (pi) and paths connecting peaks (wi,j) are used in the construction of the candidate sequence. The use of binary variables also allows us to invoke logical inference when formulating the model constraints.

The mathematical relationship between these two binary variables is provided in a subsequent section. The logical decisions imposed by the binary variables are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Decisions modeled by binary variables pi and wi,j.

(4) Boundary Conditions

As stated in the section on sets, the candidate peptide must be sequenced using ions of the same ion type. Different ion series start and end at different m/z values in the tandem mass spectrum. For instance, a candidate peptide derived using the y-ion series must begin at the weight of water (19 Da) and terminate at the weight of the parent peptide (mP + 1), whereas deriving the same sequence using the b-ion series, the appropriate bounds become 1 Da and the weight of the parent peptide subtracted by the weight of water (mP − 18), in respective order. To model this mathematically, two new sets are created which correspond to the boundary conditions at the “head” of the peptide and the “tail” of the peptide. Note that the sets presented below consider only the possibility for b- or y-ions in the candidate sequence.

| (4) |

| (5) |

Under certain conditions, it is necessary to “adjust” the elements in the boundary conditions if it is known a priori that specific peaks are missing in the spectrum, as will be described in a later section.

(5) Constraints

Several constraints derived from ion properties and graph theory are formulated in terms of the binary variables via logical inference. The first constraint exploits the fact that the candidate peptide must be sequenced using ions of the same type and that complementary ions are of different type by definition. Thus, if peak i is used to construct a candidate sequence and the peak pair (i,j) belong to the complementary ion set defined in eq 3, then peak j should be eliminated from consideration in the sequencing calculations. This is modeled mathematically by eq 6.

| (6) |

One can infer from eq 6 that if peak i is selected, then its binary variable is activated (e.g., pi = 1), which in turn deactivates the binary variable for peak j (e.g., pj = 0), and vice versa.

An obvious but important constraint to impose on the candidate sequence is that the summation of the weights of its amino acids is equal to the mass of the parent peptide (mP). It is well known that the experimentally measured parent peptide mass is subject to a certain degree of experimental error,19 which is dependent on the resolution of the mass spectrometer used. Thus, exact conservation of mass cannot be achieved but must be relaxed by some tolerance of error, as shown in eq 7 and eq 8.

| (7) |

| (8) |

The algorithm typically uses a tolerance of error of ±2 Da above and below the parent peptide mass. It is also possible to formulate the tolerance term as a variable and then incorporate it into the model such that its value is minimized.

The sequencing of the candidate peptide is best envisioned as connecting peaks in the tandem mass spectrum with paths that correspond to weights of amino acids. To ensure that the paths selected are continuous and nondegenerate, we use the flow conservation law from graph theory which has been used extensively in process synthesis problems,39–45 as shown in eq 9.

| (9) |

The above constraints ensure that the number of inputs entering a peak is equal to the number of output paths leaving a peak. To see how this constraint works, consider the spectrum graph representation for the tandem mass spectrum of a particular peptide as shown in Figure 3. One can easily see that there are several possible paths which span the spectrum graph and that for every node the number of possible input and output paths varies. Now consider the enlarged subregion of the spectrum graph shown in Figure 3. Applying eq 9 to this subregion results in the following path constraint equations:

Notice in Figure 3 that node 66 only has one input path and no output paths. Since node 66 is not an element of the boundary condition set (see eq 5), then it should be eliminated from the sequencing calculations because the sequence should not terminate at this node. This is accomplished by the first constraint equation (w61,66 = 0). Nodes 67 and 68 both have multiple input paths but only one possible output path. Let us consider only node 67 since the analysis of node 68 is similar. The equality in the constraint for node 67 implies that an output path for these nodes will be activated (i.e., w67,76 = 1) if and only if one corresponding input path is selected (i.e., w57,67 = 1 or w62,67 = 1 or w63,67 = 1). This constraint also enforces that at most one input path could be selected since only one output path exists. Furthermore, if none of the input paths are selected (i.e., w57,67 = w62,67 = w63,67 = 0) then the output path will not be activated in the construction of the sequence.

Figure 3.

Spectrum graph representation of tandem mass spectrum.

To anchor the beginning and end of the candidate sequence, the peaks denoted as the boundary conditions for the sequencing are activated, as shown in eq 10 and eq 11.

| (10) |

| (11) |

One should note that the existence for certain boundary condition elements (contained in the sets BChead and BCtail) are checked for by the preprocessing algorithm (see section on Preprocessing of Spectral Data) and can be adjusted if information is missing from the tandem mass spectrum. Furthermore, these constraints enforce the nondegeneracy of paths since only one path can initiate and terminate the sequence, respectively.

The final set of constraints constitutes the mathematical relationship between the binary variables representing the peaks, pi, and the paths connecting the peaks, wi,j̇:

| (12) |

| (13) |

These constraints ensure that if there exists a path entering and leaving a peak k (i.e., wi,k = 1 and wk,j = 1), then peak k will be activated in the construction of the candidate sequence (i.e., pk = 1). These constraints also allow the option for removing peaks (and the paths connected to these peaks) from the sequencing calculations by simply deactivating the binary variables that represents those peaks (pi). For instance, this is useful for eliminating the precursor ion and multiply charged ions from consideration.

(6) Objective Function

Although the b- and y-ion peaks are not always the greatest in intensity with respect to neighboring peaks, they are on average the most abundant in intensity throughout the entire m/z range.1 Based on this observation, the objective function is postulated as an explicit function of the peak intensities in an attempt to maximize the number of b- and y-ions used in constructing the candidate sequence. Note that prior to the model’s formulation, it is decided whether the candidate peptide is to be sequenced using the b-ion series or the y-ion series. A different objective function is formulated for each ion type since the b-ion series is sequenced N-terminus to C-terminus and vice versa for the y-ion series.

| (14) |

| (15) |

The above equations maximize the intensity of the peaks used in the construction of the candidate sequence, where the index k spans over all possible peaks and the set of indices (i,j) spans over all possible paths connecting peaks. Equation 1–Equation 15 comprise the entire mathematical model for the de novo peptide sequencing problem using tandem mass spectrometry. The entire problem formulation is summarized below for the y-ion series.

The resulting problem (P) is an ILP problem and can be solved to optimality using existing methods (e.g., CPLEX46). Throughout the remainder of this paper, the sequencing of the candidate peptides is attempted using first the y-ion series and then the b-ion series if warranted. To generate a rank-ordered list of candidate sequences, integer cuts are used to exclude previous solutions from be revisited. That is, for every solution, an integer cut is incorporated into the model using the following general form:47

| (16) |

Where

Missing Ion Peaks: Two-Stage Algorithmic Approach

The algorithm attempts to derive several candidate sequences using only single amino acid weights to connect mass peaks. However, if the spectrum is missing certain mass peaks, then it might not be possible to construct the correct sequence in this fashion. To accommodate this issue, the sequencing problem is split into two stages: stage one derives the candidate peptides using only single amino weights and stage two allows for the possibility of using two amino acid weights. That is to say, in the second stage, the additional option is available to connect two peaks via the weight of any two combined amino acids, a full list of which is available elsewhere.48 In this stage, the emphasis is again placed on primarily using the weights of single amino acids to construct the candidate sequences by penalizing the use of combined amino acid weights. This is accomplished in the objective function by multiplying the path variable corresponding to multiple residues by a penalty weighting fraction which is less than one and decreases with increasing mass error. As a result, the driving force for the algorithm is the single residue weights, while the double residue weights are utilized only to bridge the gap between disjoint single-residue segments of the candidate sequence.

Although the first- and second-stage calculations are separate, solution information from the first-stage computations is utilized in the second-stage ILP. For instance, ion peaks consistently used in the construction candidate sequences in the first stage that are of high abundance and belong to the complementary ion set (see eq 3) are activated during the second-stage calculations. The reason for activating these mass peaks is based upon the assumption that their complementary ions are in fact b-ions and a peptide derived using the b-ion series is the same as that derived by the y-ion series, but the residues are in reverse order. Thus, these complementary b-ions serve as a validation of the proposed candidate peptide that was sequenced using the y-ion series. To eliminate the derivation of the same peptide sequences, the integer cuts generated in the first stage are used in the second-stage ILP. All candidate sequences from the first- and second-stage computations are examined for consistency and validity.

PREPROCESSING OF SPECTRAL DATA

Before formulating the ILP problem, the raw tandem mass spectrum is analyzed using a preprocessing algorithm to elucidate key spectral features that can be exploited in the sequencing calculations. In particular, certain ion types are sought to confirm the proposed boundary conditions previously mentioned. First, the raw spectrum is examined for the existence of the typically abundant in intensity b2-ion,1 whose validity can be confirmed by its complementary yn−2-ion. If the corresponding yn−2-ion also exists in the spectrum, then the two possible yn−1-ions are back-calculated using the mass of the parent peptide (mP) and the weights of the amino acids that constitute the b2-ion (see Table 1), and the spectrum is once again searched to confirm these ions.

Table 1.

Ions Identified by the Preprocessing Algorithm

| ion type | relation to the b2-ion |

|---|---|

| yn−2 | mp + 2 − b2 |

| a2 | b2 − 28 |

| b1 | AA1 or AA2 |

| where AA1 + AA2 + 1 = b2 | |

| yn−1 | mp + 2 − AA1 or mp + 2 − AA2 |

| where AA1 + AA2 + 1 = b2 |

If neither of the yn−1-ions are found then this indicates that the peptide cannot be sequenced completely using the y-ion series. However, this N-terminus region of the peptide can be eliminated from the sequencing calculations by changing the “tail” boundary condition for the y-ion series (eq 5) from the mass of the parent peptide (mP) to the mass of the yn−2-ion. In other words, the sequencing of the peptide will terminate at the mass of the yn−2-ion and the unknown N-terminal amino acid pair must be determined independently. The overall framework for the preprocessing algorithm is represented conceptually by the flow chart in Figure 4, and the mathematical relationship between the important ions is provided in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Flow chart for the preprocessing algorithm.

Every b2-ion amino acid pair found by the algorithm is ranked based on the intensities of their supporting ions (i.e., yn−2, yn−1, a2, and their isotopic offsets and neutral losses of water and ammonia). However, it is important to note that ion intensities near the ends of the mass spectrum are statistically the lowest,49 which results in an N-terminal bias toward heavier amino acids. To account for this, the scores assigned to the b2-ions are normalized by their location in the tandem mass spectrum.

If the correct b2-ion does not exist in the spectrum, then the appropriate boundary conditions cannot be assigned. Such instances are easily identified since the false b2-ions found typically exhibit consistently low scores. In these cases, the algorithm searches the high-mass end of the spectrum for probable upper bounds of the y-ion series. These ion peaks are characterized by high intensities, supporting isotopes, and have a mass difference with the parent peptide equal to some combination of amino acid weights. The algorithm selects several of these ion peaks, and a presequencing ILP is formulated, which computes only the optimal candidate peptide using each ion peak as the upper bound of the y-ion series. The ion peak corresponding to the maximum objective function value from this set is then selected to be used as the appropriate boundary condition throughout the subsequent sequencing calculations. This instance commonly arises in ion trap spectra where the low-mass cutoff prevents detection of the correct b2-ion.

Certain ion peaks indicative of the C-terminal region of the peptide are also found by the preprocessing algorithm. For instance, if the peptide of interest is the product of proteolytic digestion using trypsin, then the y1-ion must be either a C-terminal lysine (K), identified by a m/z peak at 147.17, or a C-terminal arginine (R), identified by a m/z peak at 175.18.1 In the tandem mass spectra considered in this article, it is known a priori that the peptide is a tryptic peptide and this information is exploited in the sequencing calculations. In the event that neither of the two possible C-terminal peaks is found by the preprocessing algorithm, then both are added to the tandem mass spectrum with equivalent peak intensities.

The existence of immonium ions in the spectrum can also aid in the sequencing process. These ions are present in the low-mass region of the tandem mass spectrum (i.e., [30,159] Da), and although they do not provide any information regarding the position of the amino acids in the peptide, they are useful for assigning confidence to residues in the predicted sequence. A complete list of immonium ions can be found elsewhere.1,48

For high-resolution mass spectra (i.e., quadrupole time-of-flight data), the charge state of the fragment ions can be determined by the offsets of the corresponding isotopic carbon peaks. For instance, a peak with an isotopic offset of 1.0 Da indicates that the ion is singly charged, a peak with an isotopic offset of 0.5 Da indicates that the ion is doubly charged, and so on.1 The preprocessing algorithm examines the isotopic carbon offsets of ion peaks to determine its charge and then postulates new peaks in the experimental mass spectrum by multiplying each charged m/z value by its estimated charge value. Using this approach allows for the option of either keeping the originally multiply charged ions in the spectrum or eliminating them by the deactivation of their corresponding binary variables.

A common feature of low-energy CID spectra is the presence of ions representing neutral losses of ammonia (−17 Da), water (−18 Da), and carbon monoxide (−28 Da).1,48 The preprocessing algorithm identifies these ions and provides the option for deactivating these peaks in the sequencing calculations by setting their corresponding binary variables to zero. To cut down on the problem size and complexity, a filtering technique is applied to the tandem mass spectrum and only the top 125 peaks of highest intensity are used in the problem formulation.

POSTPROCESSING: SCORING CANDIDATE SEQUENCES

A subsequent scoring of the candidate peptide sequences is necessary in order to do the following: (a) assign amino acids to regions of the peptide not considered in the sequencing calculations due to boundary condition adjustments, (b) resolve doublet and triplet amino acid combinations due to missing peaks, (c) validate the “b” or “y” ions used to construct the candidate sequence by looking for other supporting ions in the raw tandem mass spectrum. For cases a and b, the weight in the candidate sequence is replaced by permutations of amino acids consistent with this mass. This results in a super set of candidate sequences whose theoretical tandem mass spectra can be predicted and compared to the experimental tandem mass spectrum for validity. Several techniques have been developed to assess the degree of similarity between the experimental and theoretical spectra for peptide sequences. In particular, probabilistic matching6,8,11 and cross-correlation3–5 have proven to be effective tools for this purpose. In this section, we describe the technique we used to assign a similarity score for a theoretical tandem mass spectrum with an experimental tandem mass spectrum.

An idealized model for predicting theoretical tandem mass spectra would incorporate residue chemistry and position dependencies into the intensity predictions. A good example of this is the 236 parameter kinetic model based on the mobile proton theory for simulation of ion trap tandem MS.30 However, this model is only applicable for ion trap spectra. Our approach is not restricted to any one type of instrument, so we adopted a generalized model for ion intensities similar to the SEQUEST model.3 That is, using a normalized scale, y- and b-ions were assigned an intensity of 1 and all other predicted ions were assigned fractions based on empirical observations.

Since only the y- or b-ion series were used in constructing the peptide sequences, it would be beneficial to utilize various other types of ions when scoring these candidate peptides in order to exploit as much information from the tandem mass spectrum as possible. In particular, the assignment of a peak as a b- or y-ion can be confirmed by the existence of supporting isotopes, neutral losses of small molecules, and multiply charged ions. It has been reported that the isotopic carbon offsets of b-ions (i.e., b + 1 and b + 2 and similarly for the y-ions) are nearly as common as the b- and y-ion series themselves and more common than various other ions, such as a-ions and ions due to neutral losses of water and ammonia.25 Isotopes of +1 were assigned an intensity of 3/4 and isotopes of +2 were given an intensity of 1/4.

The neutral losses of small molecules corresponding to losses of water, ammonia, and combinations thereof (i.e., -H2O, -NH3, -H2O-NH3, -H2O-H2O) serve as a good measure of support for the b- and y-ion series. These offsets were assigned an intensity of 1/5. However, some specific residues are more prone to losses of these molecules than others. For instance, the residues D, E, S, and T are strongly associated with neutral losses of water and the residues Q and N are strongly associated with neutral losses of ammonia.30,49 Thus, offsets consistent with the above residues were assigned an intensity of 1/3 since they are statistically more likely. Another common dissociation reaction pathway for b-ions is the elimination of carbon monoxide to form the a-ion series,50 and these ions are also assigned an intensity of 1/5. Although it has been reported that the energy of fragmentation in low-energy CID might be insufficient to break the bond between the α-carbon and the carbonyl,49 x-ions, which are offset 28 Da from y-ions, are included in the theoretical MS/MS with an intensity of 1/5.

Doubly charged b-ions were not included in the theoretical spectra to eliminate false ion peak matches because their pathway of fragmentation is not as common as that for double-charged y-ions,1 which are given normalized intensities of 1/2. It should be noted that, based on empirical observations, the double charged y-ions and a-ions are only predicted for the first half of the theoretical tandem mass spectrum.27 Also included in the peaks of this spectrum are what are known as internal fragment ions48,51–53 (ions that have lost both their C-terminal and N-terminal ends).

To introduce dependencies among the ion series, a reward/penalty system was created. For instance, a match between a predicted y-ion and a peak in the experimental spectrum is more probable if the corresponding y-ion isotopes and offsets are also found in the experimental spectrum.27 Thus, the score from a match between b- or y-ion is assigned a reward proportional to the number of its corresponding isotopes and offsets that also match with the experimental spectrum. Conversely, the existence of isotopic offsets and neutral loss ions without a corresponding y- or b-ion are penalized in the score. These conventions address the likelihood that the peaks used in the construction of the candidate sequence are actually of the b- or y-ion series.

The cross-correlation weights were selected so that specific ion types contributed in the consistent ways to the overall score. Note that if we were to consider only the y-ion series in the cross-correlation, then the resulting score would be equal to that of the objective function value for the peptide sequence. The cross-correlation function is an extension to the objective function form that incorporates other ion series in scoring the candidate sequences, and the weights for the ions were estimated in terms of their desired contributions to the score. We could have empirically measured the average intensities for these ion peaks from known spectra to derive the cross-correlation weights, but this would introduce a dependency on the set of spectra used to train the weights and on the type of instrument that generated these spectra.

It should be mentioned here that the final overall score used to select the most probable peptide is the cross-correlation score. The purpose of the objective function in the stage one and two sequencing calculations is to report a rank-ordered list of the best peptide sequences according to the form of the objective function postulated (see eq 15). In the studies presented here, 10 candidate sequences are reported from the stage one computations and 10 candidate sequences are reported from the stage two computations. The correct peptide sequence is almost always contained within this set of 20 sequences reported, which implies that the stage one and two ILP model is very effective in narrowing down the location of the correct peptide sequence from the full sequence space to a very small subset of sequences. This subset of candidate sequences are then rescored by the cross-correlation technique in order to utilize more spectrum information in the identification.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

The framework proposed in this article is for doubly charged tryptic peptides ionized via electrospray ionization. In general, multiply charged peptides are inherently more difficult to interpret because of their incomplete fragmentation (which is hypothesized to result from limited migration of the proton initially associated with the N-terminal amine moiety1) and the existence of multiply charged product ions. Singly charged peptides result in fewer product ions since during fragmentation only one group will retain the proton and hence be detected in the tandem mass spectrum. In this paper, doubly charged peptides are studied since they result in the most unambiguous fragmentation characteristics. The proposed approach can be extended to address the other charge states for tryptic peptides.

In this section, we present a comparative study with several existing de novo peptide identification methods to demonstrate the predictive capabilities of the proposed framework PILOT. The algorithms examined in the comparison, that is, Lutefisk, LutefiskXP, PepNovo, PEAKS, EigenMS, and NovoHMM, were selected on the basis of availability, reported popularity, and performance. Tandem MS for both quadrupole time-of-flight and ion trap mass spectrometers were analyzed to illustrate the proposed methods ability to accommodate instruments of varying resolution and fragmentation characteristics. In the studies presented, assignments to isobaric residues (i.e., Q and K, I, and L) are considered to be equivalent.

Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (QTOF) Spectra

To test the method’s performance on quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectra, we selected an existing data set that is publicly available.29 These spectra were collected with Q-TOF2 and Q-TOF-Global mass spectrometers for a control mixture of four known proteins: alcohol dehydrogenase (yeast), myoglobin (horse), albumin (bovine, BSA), and cytochrome c (horse). The authors defined an average signal intensity as a metric for identifying poor-quality spectra,29 and the analysis presented here was restricted to the set classified as “acceptable spectra”. A total of 38 doubly charged tryptic peptides were examined using Lutefisk, LutefiskXP, Pep-Novo, PEAKS, EigenMS, and PILOT. The performance of EigenMS on the raw tandem mass spectra is presented based on the suggestion of its authors that we use a preprocessing step for picking peaks from the raw data. The top-ranked sequence reported from each of these methods are presented in Table 2, where correctly predicted residues are underlined for reference.

Table 2.

Comparative Study for QTOF MS/MS

| Peptide | Lutefisk | LutefiskXP | PepNovo | PEAKS Online | EigenMS | PILOT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AEFVEVTK | [200.08]FVEVTK | AEFVEVTK | AEFVEVTK | AEFVEVTK | AEFEVTK | AEFEVTK |

| YLYELAR | YLYEIAR | YLYELAR | YLYELAR | YLYELAR | YLYELAR | YLYELAR |

| LKAWSVAR | LKAWSVAR | LKAWSVAR | LQAWSVVK | LAGAWSVAR | QLAWEQR | LKAWSVAR |

| ALKAWSVAR | [184.12]KAWWAR | [184.12]KAWSVAR | [186.09]EAWSAVR | ALKAWSAVR | ALKAWEKR | ALKAWSVAR |

| QTALVELLK | [229.11]TALVELLK | QTALVELLK | ETALVELLK | QTALVELLK | QTALVELLK | QTALVELLK |

| KQTALVELLK | KQTALVELLK | KQTALVELLK | QQTALVELLK | KQTALVELLK | AGQTALVELLK | KQTALVELLK |

| LVNELTEFAK | LVNELTEFAK | LVNELTEFAK | LVNELHNLT | LVNELTEFAK | LVNELTEFAK | LVNELTEFAK |

| HPEYAVSVLLR | no quality sequence found | HPEYAV[241.18]MVP | HVEYADPQQAK | HPEYAVLKNGR | FSEYAVQQRR | HPEYAVEGLLR |

| HLVDEPQNLIK | HLVDE[225.15]NLLK | HLVDENKPLLK | HLVDEPQNLLK | HLVDEPQNLLK | HLVDEPKNLIK | HLVDEPQNLIK |

| SLHTLFGDELCK | HTVTLGVYE[216.07]K | HTVTLRYPTFQ | SLHTLFTAETDK | SLHTLFGDELCK | SLHTLFGDELCK | AEHTLFGDELCK |

| YICDNQDTISSK | YL[218.07]NQDTLSSK | [NY]FAMEPTLSSK | YLSMNQDTLSSK | YLCDNQDTLSSK | YICDNQDTISSK | YICDNQDTISSK |

| LGEYGFQNALIVR | LWYGFQNALLVR | LWYGFQNALLVR | LGEYGMoQNALLVR | LGEYGFQNALLVR | LGEYGFQNALIVR | LGEYGFQNALIVR |

| VPQVSTPTLVEVSR | no quality sequence found | [PV]QVSTDPVVEWR | VPQVSTPPGCEVSR | VPQVSTPNLVNTSR | VPQVSTPLTVEVSR | VPQVSTDPVVEVSR |

| DAFLGSFLYEYSR | [186.07]FLGSFLYEYSR | WFLGSFLYEYSR | SVFLGSFLYEYSR | DAFLGSFLGSPLGMR | DAFLGSFLYEYSR | DAFLGSFLYEYSR |

| KVPQVSTPTLVEVSR | no quality sequence found | QPVSTWG[144.17]VE[305.14] | QVPQVSTPDVVEVSR | QVPQVSTLPTVEVSR | QPVQVSTPTLVEVSR | KVPQVSTPTLVEVSR |

| IGDYAGIK | no quality sequence found | LGDYAGLK | LGDYAGLK | LGDYAGLK | LGDYAGIK | IGDYAGIK |

| DIPVPKPK | [228.11]PVPKPK | NNPVPKPK | PMPVPQPK | NNPVGAPPK | NNPVPKPK | EVPVPKPK |

| EALDFFAR | [200.08]LDFFAR | EALDFFAR | EALDEDLA | EALDFFAR | AELDFFAR | EALDFFAR |

| TLPEIYEK | DVPELYEK | [214.10]PELYEK | TLPELYEK | LTPELYEK | LTPELYEK | LTPELYEK |

| ANELLINVK | [185.08]ELLLNVK | GQELLLNVK | ADQNLLNVK | ANELLLNVK | QGELLLNVK | ANELLLNVK |

| SIVGSYVGNR | [200.11]VGSYVNGR | [200.08]VGSYVGNR | EAVGSYVGNR | EAVGSYVGNR | SIVGSYVGNR | EAVGSYVGNR |

| EKDIVGAVLK | GVTDLVQVLK | [200.11]GDLVQVLK | EQDLVGAVLK | GCPDLVGAVLK | QEDLVQVLK | KEDIVGAVLK |

| STLPEIYEK | [188.08]LPELYEK | [188.06]LPELYEK | [189.71]LPELYEK | STLPELYEK | STLPEIYEK | STLPEIYEK |

| VSEAAIEASTR | VSEAALEASTR | VSEAALEASTR | VSEAAMDAAES | VSEAALEASTR | VSEAAIEASTR | VSEAAIEASTR |

| DGGEGKEELFR | DGGEGKEELFR | [172.05]WGQEELFR | DGGEGQEELMoR | DGGEGQEELFR | DGGEGKEELFR | DGGEGKEELFR |

| SISIVGSYVGNR | [200.11]SLVGYYGHR | [200.08]SLVG[288.13]HP[GP] | SLSLVGSPQLPS | LSSLVGSYVGNR | SISIVGSYVGNR | AESIVGSYVGNR |

| GAAGGLGSLAVQYAK | no quality sequence found | AQGGLGSLAVQYAK | QAGGLGSLAVPHQK | QAGGLGSLAVYAGAK | QANLGSLAVQYAK | QAGGLGSLAVQYAK |

| ANGTTVLVGMPAGAK | no quality sequence found | NQTTVLVGMKPAK | ADSATVLVGMQAPK | KGGTTVLVGMPAGAK | LVMTVLVGGATTPK | [444.18]TVLVGMPAGAK |

| GIDGGEGKEELFR | [170.11]DGGEGKEELFR | [170.11]DGGEGKEELFR | GLDGGEGQEELFR | GLDGGEGKEELFR | GIDGGEGTRELFR | GIDGGEGKEELFR |

| ADTREALDFFAR | no quality sequence found | no quality sequence found | QESVLVTDDFMoAR | WVTGSLLDFFAR | WTVAELDFFAR | [443.20]EALDFFAR |

| VLGIDGGEGKEELFR | VLGLD[242.12]WEELFR | [212.14]GLDGGEGQEELMoR | VLGLD[242.10]WEELFR | VLGLDGGEGQEELFR | VLGLDGWGKEELFR | VIGIDGGKSVEELFR |

| EDLIAYLK | DELLAYLK | EDLLAYLK | [129.09]DLLAYLK | EDLLAYLK | EDLLAYLK | EDLLAYLK |

| PNLHGLFGR | PNLHGLFGR | NPLHGLFGR | [97.07]NLHGLFGR | NPLHGLFGR | PNLHGLFGR | PNLHGLFGR |

| GLSDGEWQQVLNVWGK | no quality sequence found | [170.10]SGLMDAQQVLNVWGK | AVSDWWQQVLNVWGK | AVMAGEADKQVLGGVWGK | AVDSWWQQVLNVWGK | [558.55]WEQVLNVWGK |

| EETLMEYLENPK | EETLMEYLENPK | [EE]TLMEYLDQPK | EETLMEYLENPK | EETLMEYLENPK | EETLMEYLENPK | EETLMEYLENPK |

| TGPNLHGLFGR | TGPNLHGLFGR | [158.07]PNLHGLFGR | TGPNLHGLFGR | TGPNLHGLFGR | TGPNLHGLFGR | TGPNLHGLFGR |

| TGQAPGFTYTDANK | 199.10]SAPGFTGPTDAPGP | QASAPGFTYTDANK | TGKAPGFTYTDANK | QASAPGFTYTDANK | QASAPGFTYTWNK | TGQAPGFTYTDANK |

| EETLMoEYLNPK | EETLMoEYLENPK | [EE]TLFEYLENPK | EETLMoEYLEPNK | EETLFEYLENPK | EETLFEYLENPK | EETLMoEYLENPK |

The results reported in Table 2 can be summarized using various measures. First, consider the overall peptide identification accuracy of the de novo methods, which is reported in Table 3. In terms of correct identifications, PILOT is superior to the other de novo methods with an identification rate of ~66%, followed by PEAKS and EigenMS, both at ~53%. A common limitation of de novo methods is the inability to assign the correct N-terminal amino acid pair or resolve isobaric residues (i.e., Q or GA, W or SV, etc.). Thus, to accommodate this limitation in the comparison, we also reported the percentage of predictions for which there are only one, two, or three incorrect amino acid assignments in the entire sequence. In Table 3, it is seen that allowing for up to three incorrect amino acids increases the identification rate for all methods on the order of 30%, indicating that these limitations affect the results reported by all the de novo methods. The last entry in Table 3 reports the number of correctly assigned residues normalized by the total number of actual residues (which is 418 for the 38 doubly charged peptides considered). PILOT outperforms the other de novo methods with a residue accuracy of 91%.

Table 3.

Identification Rates for QTOF Spectra

| Lutefisk | LutefiskXP | PepNovo | PEAKS Online | EigenMS | PILOT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| correct peptides | 10 (0.263) | 9 (0.237) | 16 (0.421) | 21 (0.553) | 20 (0.526) | 25 (0.658) |

| with in 1 residue | 11 (0.290) | 10 (0.263) | 17 (0.447) | 22 (0.579) | 21 (0.553) | 25 (0.658) |

| with in 2 residue | 23 (0.605) | 22 (0.579) | 25 (0.658) | 29 (0.763) | 29 (0.763) | 33 (0.868) |

| with in 3 residue | 23 (0.605) | 25 (0.658) | 27 (0.711) | 32 (0.842) | 30 (0.790) | 35 (0.921) |

| total correct residues | 245 (0.586) | 294 (0.703) | 337 (0.806) | 366 (0.876) | 353 (0.845) | 381 (0.912) |

Another alternative metric of performance analysis is to measure the percentage of correct contiguous subsequences for up to a certain number of amino acids.25,35 Table 5 provides these values for all the de novo methods, and the overall trends are summarized in Figure 5. It is interesting to note that although LutefiskXP has a lower overall identification rate than Lutefisk (Table 3), it exhibits a much better accuracy over subsequences of varying length (as shown in Figure 5 and Table 4). Note that some of the trends in Figure 5 exhibit an increase in accuracy for correct subsequences greater than eight consecutive amino acids in length. This is because these counts are normalized by the total number of peptides that are of at least the length specified, which decreases from 37 for subsequences of length 8, to 30 for subsequences of length 9, to 25 for subsequences of length 10 (see Table 4). For each of the 38 QTOF peptides, PILOT predicts at least six consecutive amino acids correctly and performs consistently better than the other de novo methods over the entire range of subsequences considered.

Table 5.

Comparative Study for Ion Trap MS/MS

| Peptide | LutefiskXP | PepNovo | PEAKS OL | NovoHMM | EigenMS | PILOT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVLAVVSK | [214.1]LAVVSK | [213.96]LAVVSK | VDLAVVSK | VDIAVVSK | VDLAVVSK | DVLAVVSK |

| IPDEDLAGLR | DTKALDEDPP | LPDEDLAVAR | LPDEDLAVAR | IPDEDIAGIR | PLDEDLAPTK | IPDEDIAGIR |

| LSTEELLDAFK | NSTEELLDAFK | LSTEELLDAFK | LSTEELLDAFK | ISTEEIIDAFK | LSTEELLDAFK | LSTEELLDAFK |

| EAADAVLDEINER | [172.0]VDAVLDELNN[171.0] | SSPDAVLDELPMoR | ACPDAVLDELNER | ATVDAVIDEINER | DRDAVLDELRSR | DRDAVLDELNER |

| VEFEVGQSPK | [229.0]TDAVEF[210.2] | VEFEVGQSPK | VEFEVKGRR | VEFEVGKSPK | VEFEVQGPSK | VEFEVGQSPK |

| VVDAIASTPTDR | [198.1]SVLAAVC[199.1]K | [198.01]DALASTMGPGK | VVWLASTMPLK | VVDAIASTIEAR | VVDAIASTPTDR | VVDALASTVVDR |

| LIEENADLR | LLEENADLR | LLEENADLR | LLEENADLR | IIEENADIR | LLEENADLR | LLEENADLR |

| GLNSLADAVK | [170.1]NFANSHK | [169.93]NSLADAVK | VANSLCPRK | AVNSIADAVK | GLNSLAWVK | VANSLADAVK |

| VLSLAQDTADR | [212.1]SLARSMRR | PDSLAQDGDDR | LVSLAKFVRR | VISIAKDTADR | PDSLAQFVPSK | VLSLAKDTADR |

| NQAESLVYQTEK | [242.1]AESNVHSEAPK | [242.13]AESLVYQTEK | NEAESLVYKDSR | EIAESIVYKDDK | NQAESLVYQTEK | KNAESLVYKVMK |

| IAYVEIGAADVR | [184.1]YVELGAADVR | LAYVELGAADVR | LAYVELGAADVR | DGTDAAGTGAADVR | LAYVELGAADVR | IAYVEIGAADVR |

| IPDEDLAGLR | LPDEDLAAVR | LPDEDLAAQK | LPDEDLAAVR | NPDKDIAGIR | LLVEDLAGLR | LPDEDLAGLR |

| EAGQIAGLNVLR | HTFLAGLNVLR | WAKLAGLNVLR | WAQLAGLVNLR | SVAKIAGINVIR | EQQLAGLNVLR | EGAKLAGLVNIR |

| LSDGDFTLDR | LSDGDFTDRL | LSDGDMoTLDR | LSDGDFTLDR | ISDGDFTNGGR | LSDSTFPTDR | LSDGDFTVER |

| TVGDVVAYIQK | SLGDVVAYLKK | SLGDVVAYNVR | LSGDVVAPVHAK | EAGDVVAYIGAK | EAGDVVAYLQK | ISGDVVAYIQK |

| VSALLEALPK | EGALLEALPK | VSALLTLVPK | VSALLEALPK | VSAIIEAIPGA | VSALLEALPK | VSALLEALPK |

| VEFEVGQSPK | VEFEVGKRR | VEFEVGQSPK | VEFEVGKSPK | VEFEVGKSPK | KTTQGVEFPL | VEFEVGQSPK |

| YNGEEYLILSAR | [185.0]FLLYNEEGD[144.0] | YLGEEYLLLWK | YNWEYLLLWK | WFIFYIIISVK | YNWEYLLLSVK | YNVSEYLLLSAR |

| TLVAGIGGR | TLVAGLNR | TLVAGLNR | VDVAGLNR | TIVAGINR | TLVALGGGR | TLVAGLGGR |

| IPDEDLAGLR | LPDEDLAGLR | LPDMLLLAGLR | LPDFPLAGLR | IPDMIAIGIR | LVLEDLAGLR | LPDEDLAGLR |

| QVLTDAETDEVLGK | [227.1]LTDATEDEVAAR | QVLTDAPFTEVLGK | QVLTDAETDEVLGK | KVITDAEDTEVIGK | QVLTDADDDEVLGK | QVLTDAFPTEVIGK |

| EMTLLELSEFVK | TYPLL[242.1]SYVLK | FNTLLLESEEVF | FVFESMELFYK | FITIIEISEFVK | TQYESELLVDNK | METLLGGQSEFVK |

| TVGDVVAYIQK | FKKFAV[168.1][158.0]K | SLGDVVAYLQK | WWVVAYLKK | AAGDRVAYIKK | SLPSSVAYLQK | AEGDVVAYLQK |

| KDAELTASADSVR | EDAELTASADSRV | GADAELTASADSVR | QWELTASGEWR | KWEITFWKPK | AGDAELTASWWR | KDAELTASGESVR |

| KQDATVEVAIR | EGADATVKVA[142.0]K | KQDATVEVALR | KQDATVEVPSR | KKDATVEVDPK | AGQDATVEVALR | KKDATVEVAIR |

| AKLEAAGASVTVK | AKLEAAKWTVK | GAALEAAGAWTVK | AQLEAAGAWVTK | KAIEAAGAWTVK | AKLEAAKWTVK | AQLEAAGASVTVK |

| DLVDSAPKPLLEK | DLVDSAPKWHEK | DLVDSAPQPLLEK | MPVDSAPKWHEK | EVVDSAPKPIIEK | LVTDSAPQPLLEK | DLVDSAPKWHEK |

| KADLNANDIDAAAK | EANNNANDLDANR | KADLLAAASLDANR | KADLNAAASLDANR | KANIDYHIDAAAK | EANLDANDLDANR | KADNLANDLDAAAK |

| HTIFGEVVDEESQK | [238.1]LFWVVDEE[215.0]K | HTLMoGEVVDEEQSK | HTLFWVVDEEKSK | HTLFGEVVDEESKK | HTLFWVVDEESKK | HTLFGEVVDEEKSK |

| KSELIAAIR | ESELLAPSR | ESELLPWK | QSELLVRR | KSEIWPIK | AGELLAALR | KSELLAALR |

| FESELLEHVK | FVHGALLESMK | YLSAGDLEHVK | LYDTLLEHVK | FEYAIVYVVK | YLPMTLEHVK | IYSELLEHVK |

| KLSDGDFTLDR | ELSDGDFEAER | [240.26]SDGGHSNEN | ELSDGGGVLKHR | KISDGDVEYIK | GALSDGDYLLSR | QLSDGDFPYPK |

| EQQLHSLTYAYR | [258.0]KLHSLTYAYR | [257.32]QLHSLTYAYR | QQELHSLTYAYR | EKKIHSITYAYR | QEQLHSLTPHYR | EQQLHSLTYAYR |

| YNGEEYLILSAR | [278.1]GEEYLLLSAR | YNVSEYLLLSAR | YNWEYLLLSVK | YIGIFEFIISVK | YNWEYLLLSVK | YNVSEYLLLSAR |

| KGEVLDALQELTR | EWVLDALKELTR | KWVLDALQELTR | QWVLDALQELEK | KGEVIDAIKEITR | QGEVLDALCGPLTR | QGEVLDALKEITR |

| HTIFGEVVDEESQK | [239.1]LF[253.2]MDN[244.0]DK | HTLMoWVVDEEVDK | HTLFWVVDSWGDR | HTIFWVVDEETNK | HTLMHDPTWTHNK | HTLFGEVVDEESQK |

Figure 5.

Comparison of correct subsequences of varying length for quadrupole time-of-flight predictions.

Table 4.

Accuracy over Subsequences of Specified Length for QTOF Spectra

| subsequence length | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x = 3 | x = 4 | x = 5 | x = 6 | x = 7 | x = 8 | x = 9 | x = 10 | |

| no. of peptides of length ≥ x | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 30 | 25 |

| Lutefisk | 29 (0.763) | 27 (0.711) | 25 (0.658) | 22 (0.579) | 17 (0.447) | 14 (0.378) | 11 (0.367) | 10 (0.400) |

| LutefiskXP | 36 (0.947) | 34 (0.895) | 31 (0.816) | 29 (0.763) | 26 (0.684) | 19 (0.514) | 13 (0.433) | 10 (0.400) |

| PepNovo | 38 (1.000) | 36 (0.947) | 35 (0.921) | 30 (0.789) | 26 (0.684) | 21 (0.568) | 14 (0.467) | 12 (0.480) |

| PEAKS Online | 37 (0.974) | 37 (0.974) | 36 (0.947) | 36 (0.947) | 31 (0.816) | 27 (0.730) | 20 (0.667) | 16 (0.640) |

| EigenMS | 37 (0.974) | 36 (0.947) | 35 (0.921) | 33 (0.868) | 29 (0.763) | 22 (0.595) | 20 (0.667) | 16 (0.640) |

| PILOT | 38 (1.000) | 38 (1.000) | 38 (1.000) | 38 (1.000) | 34 (0.895) | 31 (0.838) | 23 (0.767) | 18 (0.720) |

Ion Trap Spectra

To evaluate the performance of the proposed approach on ion trap tandem mass spectra, we examined an experimental data set for the organism Mycobacterium smegmatis available on the Open Proteomics Database.54 The test set was constructed by selecting spectra of doubly charged peptides for which the tryptic peptide identification provided by SEQUEST had a Xcorr score greater than 2.2.55 To independently validate these identifications, each of these spectra were then searched against the NCBInr database using MASCOT.6 The spectra for which MASCOT and SEQUEST made consistent assignments were selected for subsequent analysis. These identifications were individually examined to remove assignments that appeared to be for low-quality spectra. To estimate the quality and consistency of the peak matches, eq 17 was applied to each of these ion trap spectra and their accompanying database predictions. The noise level for each spectrum was estimated using the technique described in ref 56. Those spectra of considerably lower quality scores were removed from the subsequent test set.

| (17) |

A total of 36 ion trap tandem mass spectra were selected for de novo analysis after applying the above filtering techniques. These spectra were analyzed using LutefiskXP, PepNovo, PEAKS, NovoHMM, EigenMS, and PILOT. The top-ranked sequence reported from each these methods are provided in Table 5, where correctly predicted residues are underlined for reference.

As with the quadrupole time-of-flight spectra, the results in Table 5 can be quantified using several different measures. For the 36 ion trap spectra considered, PILOT exhibits a complete identification rate of 47%. NovoHMM, which was specifically developed for analysis of ion trap spectra, has the next highest identification rate with 25%. One should note that the low m/z cutoff for ion trap tandem mass spectra makes the sequencing of the N-terminal region of the peptide substantially more difficult than for quadrupole time-of-flight spectra. To accommodate for this limitation, the identification results are once again adjusted for by allowing up to three incorrect amino acids. In Table 6, it is seen that the identification rate for all methods increases by roughly 40% when permitting up to three incorrect residue assignments. The number of correctly assigned residues normalized by the total number of actual residues (which is 408 for the 36 doubly charged peptides considered) is also reported in Table 6. PILOT outperforms the other de novo methods with an overall residue accuracy of 88%. PepNovo and NovoHMM, two commonly utilized algorithms for ion trap tandem mass spectra, both have a amino acid accuracy of 76%. EigenMS and PEAKS report similar percentages, although EigenMS outperforms PEAKS consistently throughout the analysis in Table 6.

Table 6.

Identification Rates for Ion Trap Spectra

| LutefiskXP | PepNovo | PEAKS Online | NovoHMM | EigenMS | PILOT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| correct peptides | 2 (0.056) | 8 (0.222) | 6 (0.167) | 9 (0.250) | 6 (0.167) | 17 (0.472) |

| with in 1 residue | 3 (0.083) | 9 (0.250) | 7 (0.194) | 10 (0.278) | 8 (0.222) | 17 (0.472) |

| with in 2 residue | 11 (0.306) | 20 (0.556) | 12 (0.333) | 18 (0.500) | 18 (0.500) | 29 (0.806) |

| with in 3 residue | 17 (0.472) | 23 (0.639) | 17 (0.472) | 25 (0.694) | 19 (0.528) | 32 (0.889) |

| total correct residues | 222 (0.544) | 310 (0.760) | 281 (0.689) | 309 (0.757) | 289 (0.708) | 359 (0.880) |

Table 7 reports the accuracy over predicted subsequences of specified length for the de novo methods, and the trends are summarized in Figure 6. For the entire test set, PILOT correctly identifies at least five consecutive residues. PepNovo and Novo-HMM share similar subsequence accuracies for the test set, as seen from their interweaving curves in Figure 6. Similarly, the curves for PEAKS and EigenMS also trade off in terms of subsequence accuracy. The predictions from PILOT outperform the other methods over the range of subsequences considered.

Table 7.

Accuracy over Subsequences of Specified Length for Ion Trap Spectra

| subsequence length | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x = 3 | x = 4 | x = 5 | x = 6 | x = 7 | x = 8 | x = 9 | x = 10 | |

| no. of peptides of length ≥ x | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 32 |

| LutefiskXP | 28 (0.778) | 25 (0.694) | 23 (0.639) | 20 (0.556) | 16 (0.444) | 13 (0.361) | 9 (0.257) | 8 (0.250) |

| PepNovo | 36 (1.000) | 34 (0.944) | 31 (0.861) | 27 (0.750) | 21 (0.583) | 17 (0.472) | 15 (0.429) | 12 (0.375) |

| PEAKS Online | 35 (0.972) | 34 (0.944) | 29 (0.806) | 22 (0.611) | 17 (0.472) | 13 (0.361) | 10 (0.286) | 7 (0.219) |

| NovoHMM | 35 (0.972) | 33 (0.917) | 31 (0.861) | 29 (0.806) | 21 (0.583) | 17 (0.472) | 14 (0.400) | 11 (0.344) |

| EigenMS | 34 (0.944) | 32 (0.889) | 30 (0.833) | 26 (0.722) | 17 (0.472) | 12 (0.333) | 10 (0.286) | 7 (0.219) |

| PILOT | 36 (1.000) | 36 (1.000) | 36 (1.000) | 34 (0.944) | 33 (0.917) | 30 (0.833) | 22 (0.629) | 16 (0.500) |

Figure 6.

Comparison of correct subsequences of varying length for ion trap predictions.

We have also tested PILOT, PepNovo, and EigenMS on another set of 100 doubly charged tryptic peptides constructed by Frank and Pevzner,27 and the results reveal a residue accuracy of 86.9% (876/1008) for PILOT, 84.1% (848/1008) for PepNovo, and 81.7% (824/1008) for EigenMS. Furthermore, the correct predictions within two amino acids are 87% for PILOT, 81% for PepNovo, and 77% for EigenMS. The predictions within three amino acids are 95% for PILOT, 84% for PepNovo, and 81% for EigenMS.

A component not addressed in this article is the level of confidence for the individual residues for the sequences reported, which can be computed using different techniques. Regions of high confidence can be identified by performing pairwise sequence alignment calculations on all the candidate sequences reported from the stage one and stage two computations. Using these alignments, the frequency with which certain residues appear in specific positions of the peptide can be computed. The residues of highest frequency are consistently the most accurate. Another measurement of prediction confidence on a residue basis can be inferred from the number of complementary ions found in the cross-correlation calculations. Thus, y-ions supported by complementary b-ions and other isotopic and neutral loss offset ions would be assigned a high confidence in the peptide sequence relative to y-ions with little to no supporting ions. These techniques would provide the user with confidence measures for both the individual residues and the overall peptide. This component has not been integrated into the current framework but will be introduced in future work.

CONCLUSIONS

A novel integer linear optimization framework, PILOT, was proposed for the automated de novo identification of peptides using tandem mass spectroscopy. PILOT is the first reported ILP formulation for the peptide identification problem that can introduce integer cuts to generate a rigorous rank-ordered list of candidate sequences, introduce complementary ions into the sequencing calculations, and allow for the error tolerance to be introduced as a variable term. For a given experimental MS/MS spectrum, PILOT generates a rank-ordered list of potential candidate sequences and a cross-correlation technique is employed to assess the degree of similarity between the theoretical tandem mass spectra of predicted sequences and experimental tandem mass spectra. A comparative study for a total of 174 spectra from both quadrupole time-of-flight and ion trap mass spectrometers was presented to benchmark the performance of the proposed framework with several existing methods. The CPU requirements for the PILOT ranged from about 5 to 20 s per tandem mass spectrum on a Intel Pentium 4 3.0GHz Linux-based computer. For the case studies presented, PILOT consistently outperformed the other de novo methods in several measures of prediction accuracy. This high degree of confidence for the predictions made by a de novo algorithm is important for the effective use of a homology search program to determine positive hits in a protein database since the slightest variability in a peptide sequence can lead to false protein matches.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA (R 832721-010), Siemens Corporation, and the National Institutes of Health. Although the research described in the article has been funded in part by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s STAR program through grant R 832721-010, it has not been subjected to any EPA review and therefore does not necessarily reflect the views of the Agency, and no official endorsement should be inferred.

References

- 1.Kinter M, Sherman NE. Protein Sequencing and Identification using Tandem Mass Spectrometry. New York: John Wiley and Sons Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yates JR., III Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2004;33:297–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.111502.082538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yates JR, Eng JK, McCormack AL, Schieltz D. Anal. Chem. 1995;67:1426–1436. doi: 10.1021/ac00104a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yates JR, Eng JK, McCormack AL. Anal. Chem. 1995;67:3202–3210. doi: 10.1021/ac00114a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perkins DN, Pappin DJC, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pevzner PA, Mulyukov Z, Dancik V, Tang CL. Genome Res. 2001;11:290–299. doi: 10.1101/gr.154101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bafna V, Edwards N. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:S13–S21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.suppl_1.s13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadygov RG, Yates JR. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:3792–3798. doi: 10.1021/ac034157w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez P, Gras R, Frey J, Appel RD. Proteomics. 2003;3:870–878. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havilio M, Haddad Y, Smilansky Z. Anal. Chem. 2003;75(3):435–444. doi: 10.1021/ac0258913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore RE, Young MK, Lee TD. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2002;13:378–386. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(02)00352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacCoss MJ, Wu CC, Yates JR. Anal. Chem. 2003;74:5593–5599. doi: 10.1021/ac025826t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenyo D, Beavis RC. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:768–774. doi: 10.1021/ac0258709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson DC, Li W, Payan DG, Noble WS. J. Proteome Res. 2003;2:137–146. doi: 10.1021/pr0255654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nesvizhskii AI, Aebersold R. Drug Discovery Today. 2004;9(4):173–181. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02978-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor JA, Johnson RS. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1997;11:1067–1075. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0231(19970615)11:9<1067::AID-RCM953>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dancik V, Addona TA, Clauser KR, Vath JE, Pevzner PA. J. Comp. Biol. 1999;6(3):327–342. doi: 10.1089/106652799318300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez de Cossio J, Gonzalez J, Satomi Y, Shima T, Okumura N, Besada V, Betancourt L, Padron G, Shimonishi Y, Takao T. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:1694–1699. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000501)21:9<1694::AID-ELPS1694>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen T, Kao MY, Tepel M, Rush J, Church GM. J. Comp. Biol. 2001;10(3):325–337. doi: 10.1089/10665270152530872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor JA, Johnson RS. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:2594–2604. doi: 10.1021/ac001196o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lubeck O, Sewell C, Gu S, Chen X, Cai DM. Proc. IEEE. 2002;90(12):1868–1874. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarman KD, Cannon WR, Jarman KH, Heredia-Langner A. 3rd IEEE International Symposium on BioInformatics and BioEngineering. Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE Computer Society; 2003. A model of random sequences for de novo peptide sequencing; pp. 206–213. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cannon WR, Jarman KD. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:1793–1801. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen T, Bingwen L. J. Comp. Biol. 2003;10(1):1–12. doi: 10.1089/106652703763255633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frank A, Pevzner P. Anal. Chem. 2005;77(4):964–973. doi: 10.1021/ac048788h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bern M, Goldberg D. J. Comp. Biol. 2006;13(2):364–378. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2006.13.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma B, Zhang KZ, Hendrie C, Liang C, Li M, Doherty-Kirby A, Lajoie G. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:2337–2342. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Z. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:3908–3922. doi: 10.1021/ac049951b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Z. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:6374–6383. doi: 10.1021/ac0491206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heredia-Langner A, Cannon WR, Jarman KD, Jarman KH. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(14):2296–2304. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malard JM, Heredia-Langner A, Baxter DJ, Jarman KH, Cannon WR. Constrained de novo peptide identification via multi-objective optimization. HiCOMB Proceedings. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malard JM, Heredia-Langner A, Cannon WR, Mooney R, Baxter DJ. Concurrency Comput. Pract. Exp. 2005;17:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischer B, Roth V, Roos F, Grossmann J, Baginsky S, Widmayer P, Gruissem W, Buhmann JM. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:7265–7273. doi: 10.1021/ac0508853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mann M, Wilm M. Anal. Chem. 1994;66:4390–4399. doi: 10.1021/ac00096a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tabb DL, Saraf A, Yates JR. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:6415–6421. doi: 10.1021/ac0347462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sunyaev S, Liska AJ, Golod A, Shevchenko A, Shevchenko A. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:1307–1315. doi: 10.1021/ac026199a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schrijver A. Theory of Linear and Integer Programming. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Floudas CA, Grossmann IE. Comp. Chem. Eng. 1987;11(4):319–336. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Floudas CA, Anastasiadis SH. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1988;43(9):2407–2419. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paules GE, IV, Floudas CA. Oper. Res. J. 1989;37(6):902–915. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ciric AR, Floudas CA. Comp. Chem. Eng. 1989;13(6):703–715. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aggarwal A, Floudas CA. Comp. Chem. Eng. 1990;14(6):631–653. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kokossis AC, Floudas CA. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1994;49(7):1037–1051. [Google Scholar]

- 46.CPLEX. ILOG CPLEX 9.0 User’s Manual. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Floudas CA. Nonlinear and Mixed-Integer Optimization. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papayannopoulos IA. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 1995;14:49–73. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabb DL, Smith LL, Breci LA, Wysocki VH, Lin D, Yates JR. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:1155–1163. doi: 10.1021/ac026122m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yalcin T, Csizmadia IG, Peterson MR, Harrison AG. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1996;7:233–242. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(95)00677-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burlet O, Yang CY, Gaskell SJ. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1992;3:337–344. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(92)87061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hunt DF, Yates JR, Shabanowitz J, Winston S, Hauer CR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1986;83:6233–6237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bean MF, Carr SA. Anal. Chem. 1991;63:1473–1481. doi: 10.1021/ac00014a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. http://bioinformatics.icmb.utexas.edu/OPD/

- 55.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Purvine S, Kolker N, Kolker E. OMICS. 2004;8(3):255–265. doi: 10.1089/omi.2004.8.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]