Abstract

The metabolic syndrome is a complex clustering of metabolic defects associated with physical inactivity, abdominal adiposity, and aging.

Purpose

To examine the effects of exercise training intensity on abdominal visceral fat (AVF) and body composition in obese women with the metabolic syndrome.

Methods

Twenty-seven middle-aged, obese women (mean ± SD; age: 51 ± 9 years and body mass index: 34 ± 6 kg/m2) with the metabolic syndrome completed one-of-three 16-week aerobic exercise interventions: (i) No Exercise Training (Control): Seven participants maintained their existing levels of physical activity, (ii) Low-Intensity Exercise Training (LIET): eleven participants exercised 5 days · week-1 at an intensity ≤ lactate threshold (LT) (iii) High-Intensity Exercise Training (HIET): nine participants exercised 3 days · week-1 at an intensity > LT and 2 days ·week-1 ≤ LT. Exercise time was adjusted to maintain caloric expenditure (400 kcal·session-1). Single-slice computed tomography scans obtained at the L4-L5 disc-space and mid-thigh were used to determine abdominal fat and thigh muscle cross-sectional areas. Percent body fat was assessed by air displacement plethysmography.

Results

HIET significantly reduced total abdominal fat (p<0.001), abdominal subcutaneous fat (p=0.034) and AVF (p=0.010). There were no significant changes observed in any of these parameters within the Control or LIET conditions.

Conclusions

The present data indicate that body composition changes are affected by intensity of exercise training with HIET more effective for reducing total abdominal fat, subcutaneous abdominal fat and AVF in obese women with the metabolic syndrome.

Keywords: Physical Activity, Weight Loss, Metabolic Syndrome, Diabetes, Cardiovascular, Human

INTRODUCTION

The metabolic syndrome is a complex clustering of cardiometabolic abnormalities associated with aging, physical inactivity, and abdominal adiposity (5; 12; 18). Globally, the incidence of the metabolic syndrome and its associated increase in cardiometabolic risk has reached pandemic proportions. Of the risk factors used to identify the metabolic syndrome, elevated abdominal visceral fat (AVF) has consistently been shown to be associated with increased cardiometabolic risk (30). The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) consensus statement (2) identified central obesity as the unifying cardiometabolic risk factor among individuals with the metabolic syndrome. Researchers and clinicians world-wide are intensively investigating both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches to reduce visceral adiposity and its related comorbidities.

Exercise training provides an economically viable, non-pharmacological approach for eliciting beneficial adaptations in body composition and cardiometabolic risk. In support of this contention, endurance training has been shown to be a powerful strategy for inducing abdominal fat loss, particularly with respect to AVF loss (16; 23; 27; 31). Despite much interest in exercise-induced fat loss, the optimal exercise prescription to maximize fat loss remains elusive. Only a limited number of exercise interventions have systematically examined the impact of endurance training intensity on fat loss and in particular AVF loss under equivalent energy expenditures (36; 37). It may be postulated that high-intensity endurance training (HIET) may induce greater fat loss, in particular AVF loss than low-intensity endurance training (LIET) for several reasons. First, HIET induces secretion of lipolytic hormones including growth hormone and epinephrine (32; 33), which may facilitate greater post-exercise energy expenditure and fat oxidation. Second, it has been reported that under equivalent levels of energy expenditure HIET favors a greater negative energy balance compared to LIET (21). In the present study we examined the impact of endurance training intensity on AVF under equivalent caloric expenditure (2000 kcal·week-1). We hypothesized that sixteen weeks of endurance training above the lactate threshold (LT) (i.e., high-intensity endurance training) would result in a greater reduction in AVF and more favorable changes in body composition than 16 weeks of endurance training below the LT (i.e., low-intensity endurance training) in abdominally obese women with the metabolic syndrome.

METHODOLOGY

Participants

Twenty-seven middle aged (mean ± SD; 51 ± 9 y) women who met the IDF criteria for the metabolic syndrome (2) completed the present study. To meet the IDF criteria for the metabolic syndrome each participant had to have an elevated waist circumference (≥ 80 cm) and at least two of the following; elevated fasting blood glucose (≥ 100 mg/dL), low HDL-C (≤ 50 mg/dL), hypertriglyceridemia (≥ 150 mg/dL), and/or elevated blood pressure (≥ 130/85 mm Hg) (2). The participants were sedentary at baseline, reporting less than 2 days per week of structured exercise. All participants underwent an initial eligibility screening in the University of Virginia’s General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) (see below). The Institutional Review Board, Human Investigation Committee of the University of Virginia’s Health System approved this study, and each participant provided written informed consent.

Metabolic Syndrome and Medical Screening Protocol

Participants reported to the GCRC for screening after a 10 to 12 h fast at ∼0900 h. Participants provided a detailed medical history and underwent a physical examination, which included an assessment of the five risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome as defined by the IDF (2). In brief, waist circumference measurements were taken in triplicate to the nearest 0.1 cm using a non-elastic measuring tape, midway between the iliac crest and the lowest rib (28). Seated blood pressure was assessed in duplicate using an automated sphygmomanometer (Dynamap 100, General Electric, Tampa, FL) after participants sat quietly for 10 to 15 minutes. Fasting blood samples were then drawn and serum was separated by centrifugation. Glucose, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations were assessed in serum. Glucose concentrations were determined by using an automated glucose analyzer (YSI Instruments 2300 STAT Plus, Yellow Springs, OH). Triglycerides and HDL-C concentrations were determined using an Olympus AU640 automatic analyzer (Olympus, Melville, NY). All participants were asked to refrain from caffeine, alcohol, and vigorous physical activity for 24 hours prior to testing. Exclusion criteria included a history of ischemic heart disease, diabetes, pulmonary or musculoskeletal limitations to exercise, and the use of vasoactive medications, oral hypoglycemics, insulin, glucocorticoids, anti-psychotics, hormone replacement or birth control, and if pregnant, breast feeding, or unwilling to provide written informed consent.

Study Design

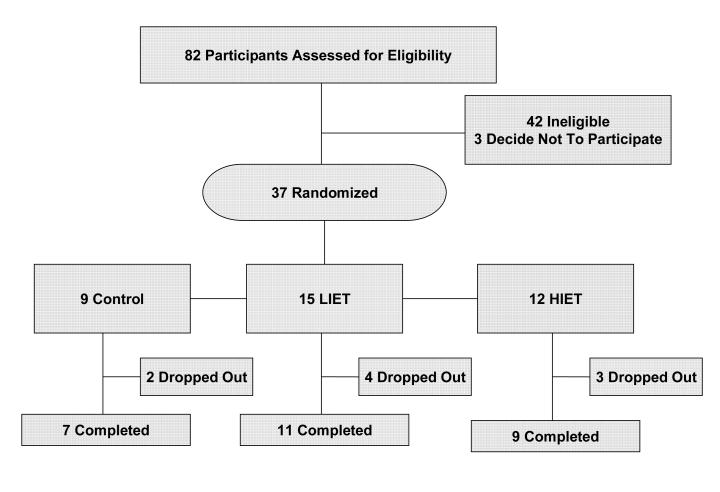

Eligible participants were randomized to one of three 16-week exercise training conditions: (i) no-exercise training (Control), (ii) low-intensity exercise training (LIET), or (iii) high-intensity exercise training (HIET). Figure 1 presents the distribution of study participants. Participants were assessed before and after the 16-week intervention. Participants were admitted to the GCRC for 2 days during which the following evaluations were performed (see below). The one exception was the cardiorespiratory fitness assessment, which was conducted as an outpatient visit. To control for the effects of menstrual cycle on outcome variables, premenopausal women were admitted between days 2-8 of their menstrual cycle. Postmenopausal status was determined by the absence of menses for > 1 year. In the NOET condition there was 1 premenopausal woman, 1 woman who underwent a hysterectomy (menopausal status unknown), and 5 postmenopausal women, in the LIET condition there were 3 premenopausal women, 4 women who underwent a hysterectomy (menopausal status unknown), and 4 postmenopausal women, and in the HIET there were 2 premenopausal were, 2 women who underwent a hysterectomy (menopausal status unknown), and 7 postmenopausal women. Participants were asked to refrain from alcohol, caffeine, and cigarette smoking for at least 72 h prior to their admission.

Figure 1.

Distribution of study participants.

Body Composition Assessment

Body composition was measured using air displacement plethysmography (Bod-Pod, Life Measurement Instruments, Concord, CA) corrected for thoracic gas volume as described previously (7).

Single-slice computed tomography (CT) images were obtained at the level of L4-L5 inter-vertebral disc space and at the mid-point between the inguinal crease and the top of the patella as previously described (22). All scans were performed using a General Electric Lightspeed CT (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) scanner and saved as DICOM images for analysis. Standard CT procedures of 120 kV, 5 mm thickness and a 512 X 512 matrix were used for all subjects. A single trained investigator analyzed each of the blinded CT images using the Slice-O-Matic version 4.3 software (Tomovision, Montreal, Canada) package for the delineation and quantification of cross-sectional areas of fat, muscle, and bone as previously described (22; 29). The measurement boundary for AVF was defined as the innermost aspect of the abdominal and oblique muscle walls and the posterior aspect of the vertebral body, as described previously (6). In addition, we also quantified abdominal subcutaneous fat area at the L4-L5 intervertebral disc space. At the mid-thigh, we assessed the total mid-thigh fat area and the total mid-thigh skeletal muscle area. The inter- and intra-investigator coefficient of variations for these analyses in our laboratory are less than 5% (22).

Cardiorespiratory Fitness Assessment

Participants completed a continuous VO2 Peak treadmill protocol. The initial treadmill (Quinton Q65, Seattle, WA) velocity was 60 m·min-1 and the velocity was increased by 10 m·min-1 every 3 minutes until volitional fatigue. Metabolic data were collected during the protocol using standard open-circuit spirometric techniques (Viasys Vmax 229, Yorba Linda, CA) and heart rate was assessed electrocardiographically (Marquette Max-1 electrocardiograph, Marquette, WI). VO2 Peak was chosen as the highest VO2 attained during the exercise protocol. An indwelling venous cannula was inserted in a forearm vein and blood samples were taken at rest and at the end of each exercise stage for the measurement of blood lactate concentration (YSI Instruments 2300 STAT Plus, Yellow Springs, OH). The LT was determined from the blood lactate-velocity relationship and was defined as the highest velocity attained prior to the curvilinear increase in blood lactate concentrations above baseline (43). A lactate elevation of at least 0.2 mM (the error associated with the lactate analyzer) was required for LT determination. Individual plots of VO2 vs. velocity allowed for the determination of the VO2 associated with the lactate threshold. The respiratory exchange ratio (RER), heart rate and blood lactate responses were monitored to insure that participants attained peak values at the point of volitional exhaustion. VO2 peak was chosen as the highest VO2 attained during the test.

Physical Activity and Dietary Assessment

The time spent in physical activity at different intensities was assessed using the Aerobic Center Longitudinal Study’s Physical Activity Questionnaire (26). The questionnaire was administered using an interview technique to increase accuracy (34). Total physical activity was calculated as MET·H·Week-1 (1 MET = 3.5 ml·kg·min-1), using the Compendium of Physical Activities (1). Participants were instructed by a registered dietician on how to complete a 3-day dietary record, which was analyzed using a commercially available nutrition software program (The Food Processor SQL, ESHA Research, Salem, OR).

Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)

After an overnight fast, participants were awakened at 0600 h, asked to void, return to bed and remain awake in the supine position for 30 min in a quiet and thermo-neutral environment. BMR was measured by indirect calorimetry (Sensor Medics Delta Trac metabolic cart and ventilation hood) for 30 min.

Exercise Intervention

Participants were randomized to the one of the following three interventions: (i) no-exercise training, (ii) low-intensity exercise training, or (iii) high-intensity.

No-Exercise Training (Control): Participants maintained their current level of physical activity for the duration of the study.

Low-Intensity Exercise Training (LIET): Participants completed a 16-week supervised low-intensity exercise intervention. Participants were progressed to complete five exercise sessions (days) per week by week 5 at an intensity at or below their LT (RPE ∼ 10-12). The duration of each exercise session was adjusted based on each participant’s individual VO2-velocity relationship so that each participant expended a total of 300 kcal per training session for weeks 1-2 (3 days/week), 350 kcal per session for weeks 3-4 (4 days/week), and 400 kcal per session for weeks 5-16 (5 days/week). As each participant’s fitness level improved the velocity required to maintain her assigned RPE was increased, therefore the duration was readjusted to maintain kcal requirement. Exercise was prescribed based on the rating of perceived exertion obtained during the LT / VO2 Peak protocol and one of the investigators monitored RPE during each training session.

High-Intensity Exercise Training (HIET): Participants completed a 16-week supervised moderate-high intensity exercise intervention. Participants were progressed to five exercise sessions (days) per week by week 5. Three days per week (e.g., M, W, F) participants exercised at an intensity midway between the LT and VO2 peak (RPE ∼ 15-17) and the remaining two days (e.g., T, Th) they exercised at or below their LT (RPE ∼ 10-12). The progression of caloric expenditures and velocity and duration adjustments were made as described for LIET, with the exception that participants always had 3 days/week > LT and one < LT training session was added at week 3 and again at week 5.

All exercise training sessions were supervised by a member of the investigative team and took place at the UVA indoor or outdoor track. Each participant was instructed to walk/run the distance associated with their prescribed caloric expenditure based on each participant’s body weight and associated caloric output from the Compendium of Physical Activity. If participants lost weight the distance required to expend a given energy expenditure increased accordingly. For example, a 90 kg woman would complete 3.5 miles per session to expend 400 kcal per session, whereas, an 80 kg woman would complete 4.0 miles per session.

The rationale for using RPE as an index of training intensity comes from our previous data that suggest that RPE is an accurate marker of the blood lactate response to exercise that is not affected by gender, fitness, training state, mode of exercise, or intensity of training (20; 35; 38) and that RPE can be used to produce a desired blood lactate concentration during 30-min of treadmill running (38). Additionally, Jakicic et al. (24) reported that RPE provide a more accurate marker of relative exercise intensity compared to % of heart rate reserve in obese women before and after weight loss. Each participant’s RPE was monitored on a lap-by-lap basis to assess the prescribed exercise intensity and the velocities to required to maintain the assigned RPE were adjusted accordingly. Heart rate data were not collected during the exercise sessions, however, as stated above RPE have been shown to be an accurate marker of relative exercise intensity among obese adults.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (SAS Version 9.1, Cary, NC). Since measurements of the responses at 16 weeks were required for the participant to be included in the analysis, our target study population with respect to statistical inference was the population of individuals who met the study inclusion criteria and who successfully completed the 16-week intervention. The frequency of patient dropouts was analyzed across the 3 interventions to determine whether the dropout rate was at random or if it was associated with the participants’ treatment assignment. Data are presented as means ± SDs.

The present study was powered to detect a ∼ 30 cm2 reduction in AVF (ΔAVF = baseline minus 16-week AVF measurement) with 12 participants per group. Two-way, mixed-effects analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was employed to examine mean differences in pre- to posttraining values (14). The model specification included parameters to estimate the exercise intensity main effect (Control, LIET, and HIET), the time main effect (pre- and posttraining), and their interaction effect on the change in the dependent variables. Their baseline value served as the covariate. In addition, the model included random effects which represented the between and within-subject error terms. The model parameters were estimated based on the principles of restricted maximum likelihood, with the variance-covariance structure estimated using unstructured estimate. For all analyses, pair-wise comparisons of the means were conducted when the main effect of group, time or the interaction between group*time were significant. Fisher’s Restricted Least Significant Differences criterion was utilized to maintain the a priori type I error rate of 0.05. In addition, we conducted ANCOVA analyses using menopausal status as a covariate (data not shown). As we did not observe any significant effects of menopausal status on any of the outcome measures group data are presented. Spearman rank correlations were calculated to test the association among changes in weight, fat mass, waist circumference, and the metabolic syndrome parameters.

RESULTS

Pretraining Characteristics and Exercise Adherence

Tables 1-3 present the mean ± SDs pre- and posttraining values for the metabolic syndrome parameters, body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, physical activity, and basal metabolic rate by treatment condition. There were no significant differences among the three conditions at baseline for any outcome measure (all p > 0.1; Tables 1-3). Table 4 presents the summary data for exercise adherence, volume, and intensity. Both the LIET and HIET groups had similar exercise adherence, with ∼79 ± 3% and ∼83 ± 3% of the assigned exercise sessions completed within each exercise condition, respectively. We did not observe a differential rate in dropouts among the three conditions (Figure 1). During LIET exercise sessions the mean RPE was ∼ 11; for HIET, the mean RPE was ∼15 during the HIET sessions and ∼12 during the LIET sessions. By design, the mean velocity per session and the mean RPE per session were significantly higher in the HIET group during their HIET days compared to the LIET group. There were no statistically significant differences between the two training groups for the total estimated caloric energy expenditure.

Table 1.

The effects of 16-weeks of either no exercise training (Control, n = 7), low-intensity exercise training (LIET, n = 11), or high-intensity exercise training (HIET, n = 9)on the parameters associated with the metabolic syndrome.

| NOET | LIET | HIET | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretraining | Posttraining | Pretraining | Posttraining | Pretraining | Posttraining | ANCOVA, p-value (Treatment, Time, Interaction) |

|

| Waist Circumference, cm | 98.2 ± 10.0 | 97.5 ± 8.0 | 103.8 ± 10.6 | 102.6 ± 10.4 | 103.7 ± 16.8 | 98.1 ± 13.3*¥Ψ | (0.036, 0.020, 0.055) |

| Fasting Blood Glucose, mg.dL-1 | 107.7 + 14.6 | 110.4 + 16.6 | 106.7 + 13.5 | 104.0 + 10.8 | 110.2 + 20.6 | 113.8 + 26.0 | (0.675, 0.066, 0.658) |

| HDL-C, mg.dL-1 | 42.7 ± 6.7 | 45.7 ± 9.1 | 44.6 ± 6.6 | 49.0 ± 10.4 | 50.9 ± 10.7 | 52.1 ± 9.1 | (0.181, 0.085, 0.233) |

| Triglycerides, mg.dL-1 | 187.3 ± 77.0 | 191.5 ± 97.3 | 241.9 ± 202.4 | 213.8 ± 135.8 | 152.1 ± 43.9 | 126.7 ± 40.0 | (0.245, 0.175, 0.552) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 129 ± 12 | 130 ± 11 | 135 ± 17 | 124 ± 10*,¥ | 124 ± 16 | 123 ± 15 | (0.207, 0.087, 0.046) |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 75 ± 7 | 76 ± 7 | 82 ± 12 | 78 ± 10 | 76 ± 8 | 74 ± 8 | (0.706, 0.469, 0.549) |

Two-way, mixed-effects analysis of variance of covariance with repeated measures (ANCOVA) was employed to examine mean differences in pre-to posttraining values, with the baseline values serving as the covariate (see methods for details). For all analyses, linear contrasts of the means were constructed to test our a priori hypotheses. Fisher’s Restricted Least Significant Differences criterion was utilized to maintain the a priori type I error rate of 0.05.

Significantly different from baseline (p <0.05)

Significant treatment effect (post — pre) compared with NOET (p <0.05)

Significant treatment effect (post — pre) compared with LIET (p <0.05)

Table 3.

The effects of exercise training intensity on various cardiometabolic risk factors in obese women with the metabolic syndrome following 16 weeks of either no exercise training (Control, n = 7), light-intensity exercise training (LIET, n = 11), or high-intensity exercise training (HIET, n = 9).

| Control | LIET | HIET | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretraining | Posttraining | Pretraining | Posttraining | Pretraining | Posttraining | ANCOVA, p-value (Treatment, Time, Interaction) |

|

| VO2 Peak, ml·kg-1·min-1 | 21.6 ± 4.1 | 20.9 ± 2.8 | 21.0 ± 3.5 | 22.8 ± 2.6* | 21.7 ± 4.1 | 24.7 ± 4.6*,¥ | (0.025, 0.023, 0.049) |

| VO2 LT ,ml·kg-1·min-1 | 13.0 ± 2.5 | 14.5 ± 1.9 | 13.0 ± 2.1 | 13.2 ± 1.8 | 13.8 ± 2.3 | 14.6 ± 2.4 | (0.469, 0.042, 0.704) |

| Treadmill VelocityPeak, m·min-1 | 113 ± 10 | 116 ± 5 | 114 ± 13 | 124 ± 14* | 116 + 10 | 136 ± 24*,¥,Ψ | (0.022, <0.001, 0.017) |

| Treadmill VelocityLT, m·min-1 | 81 ± 9 | 90 ± 10 | 84 ± 7 | 87 ± 5 | 84 ± 10 | 88 ± 8 | (0.503, 0.003, 0.582) |

| MET-H.Week-1 | 118.7 ± 46.6 | 152.2 ± 23.2 | 127.7 ± 53.5 | 122 ± 45 | 123.9 ± 56.6 | 149 ± 27 | (0.157, 0.157, 0.374) |

| Basal Metabolic Rate, Kcal·day-1 | 1578 ± 150 | 1522 ± 103 | 1688 ± 294 | 1622 ± 263 | 1671 ± 284 | 1688 ± 187 | (0.254, 0.574, 0.445) |

Two-way, mixed-effects analysis of variance of covariance with repeated measures (ANCOVA) was employed to examine mean differences in pre-to posttraining values, with the baseline values serving as the covariate (see methods for details). For all analyses, linear contrasts of the means were constructed to test our a priori hypotheses. Fisher’s Restricted Least Significant Differences criterion was utilized to maintain the a priori type I error rate of 0.05.

Significantly different from baseline (p <0.05)

Significant treatment effect (post — pre) compared with NOET (p <0.05)

Significant treatment effect (post — pre) compared with LIET (p <0.05)

Table.

Mean (SEM)[median] exercise data by treatment group.

| LIET | HIET | ANOVA p-value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIET | HIET | |||

| RPE·Session-1 | 11.1 (2.1) [11.2] |

12.2 (0.6) [11.7] |

15.4 (0.4) [15.7]¥,Ψ |

<0.001 |

| Miles·Session-1 | 3.0 (0.2) [3.0] |

3.4 (0.2) [3.2]¥ |

3.3 (0.2) [3.1] |

0.001 |

| Time (min) | 53 (3) [50] |

59 (2) [60]¥ |

53 (2) [52]Ψ |

<0.001 |

| Velocity·Session-1( Miles·Hour-1) | 3.4 (0.1) [3.4] |

3.4 (0.2) [3.4] |

3.7 (0.2) [3.7]¥,Ψ |

<0.001 |

| Session Adherence (%) | 79 (2) [78] |

82 (3) [82] |

NS | |

| Total·Kcal | 22,480 (705) [22,308] |

23,370 (716) [23,452] |

NS | |

Significant treatment effect compared with NOET (p <0.05)

Significant treatment effect compared with LIET (p <0.05)

The RPE·session-1, miles·session-1, time·session-1, velocity·session-1 represent the mean exercise data. The session adherence is presented as the percent of total sessions completed and total kcal is derived from the session adherence * total prescribed kcal (28600 kcal).

Metabolic Syndrome Parameters

By design, all participants had elevated waist circumference and at least two of the following; elevated fasting blood glucose, low HDL-C, hypertriglyceridemia, and were normotensive to mildly hypertensive at baseline (Table 1). HIET significantly reduced waist circumference (p = 0.001), which was significantly greater than the reductions observed in response to Control and LIET (p = 0.039 and p = 0.035, respectively; Table 1) after adjusting for the baseline values. LIET significantly reduced systolic blood pressure (p = 0.002), which was significantly greater than the reduction observed in response to Control (p = 0.023; Table 1) after adjusting for the baseline values. However, the remaining metabolic syndrome parameters remained unchanged.

Body Composition

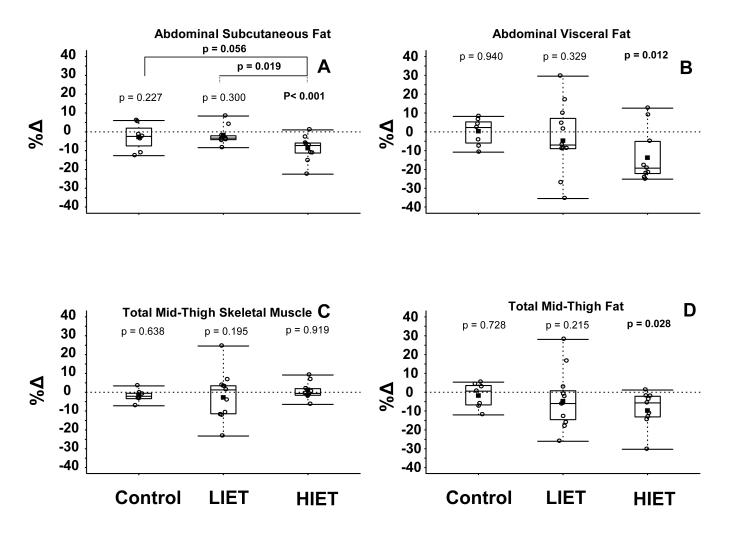

HIET significantly reduced total abdominal fat (p < 0.001, Table 2), AVF (p = 0.010; Table 2 and Figure 2c) and abdominal subcutaneous fat (p = 0.034; Table 2 and Figure 2d) after adjusting for the baseline values. There were no significant changes observed in any of these parameters within the Control or LIET conditions. The reductions in total abdominal fat and abdominal subcutaneous fat cross-sectional areas in the HIET condition were significantly greater than those observed in the LIET condition (p = 0.017 and p = 0.033, respectively) after adjusting for the baseline values. Although the reduction in AVF within HIET condition (-24 cm2) was much greater than that observed within Control condition (-2 cm2) and the LIET condition (-7 cm2) these differences did not reach the level of statistical significance across conditions (p = 0.098 and p = 0.153, respectively). HIET also significantly reduced total mid-thigh fat (p = 0.001; Table 2 and Figure 2e). We did not observe a significant change in total mid-thigh skeletal muscle among the three treatment conditions (p > 0.1; Table 2 and Figure 2d). HIET significantly reduced total body weight (p = 0.013), BMI (p = 0.009), and fat mass (p = 0.011) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The effects of 16-weeks of either no exercise training (Control, n = 7), low-intensity exercise training (LIET, n = 11), or high-intensity exercise training (HIET, n = 9) on measures of body composition in obese women with the metabolic syndrome.

| Control | LIET | HIET | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretraining | Posttraining | Pretraining | Posttraining | Pretraining | Posttraining | ANCOVA, p-value (Treatment, Time, Interaction) |

|

| Weight, kg | 89.6 ± 11.2 | 88.7 ± 10.6 | 97.2 ± 22.0 | 95.1 ± 19.3 | 93.5 ± 18.3 | 90.0 ± 15.6* | (0.294, 0.009, 0.427) |

| Body Mass Index, m.kg-2 | 32.7 ± 3.8 | 32.4 ± 3.8 | 34.7 ± 7.5 | 33.9 ± 6.5 | 34.7 ± 6.8 | 33.4 ± 5.6* | (0.370, 0.009, 0.366) |

| Body Fat, % | 45.1 ± 3.3 | 45.0 ± 3.7 | 44.0 ± 4.9 | 43.6 ± 4.1 | 43.5 ± 4.8 | 41.8 ± 5.4 | (0.181, 0.085, 0.233) |

| Fat Free Mass, kg | 49.2 ± 6.5 | 48.7 ± 8.8 | 54.2 ± 11.5 | 53.3 ± 9.4 | 52.2 ± 7.2 | 51.7 ± 5.7 | (0.747, 0.233, 0.925) |

| Fat Mass, kg | 40.4 ± 6.2 | 40.1 ± 6.3 | 43.1 ± 11.5 | 41.8 ± 11.2 | 41.0 ± 7.2 | 38.2 ± 10.7* | (0.203, 0.020, 0.296) |

| Abdominal Fat, cm2‡ | 672 ± 92 | 644 ± 75 | 647 ± 116 | 636 ± 121 | 683 ± 183 | 625 ± 181*Ψ | (0.057, <0.001, 0.045) |

| Subcutaneous Fat, cm2‡ | 496 ± 80 | 480 ± 73 | 486 ± 143 | 475 ± 138 | 513 ± 163 | 467 ± 151*Ψ | (0.063, 0.001, 0.043) |

| Abdominal Visceral Fat, cm2‡ | 157 ± 71 | 155 ± 71 | 153 ± 51 | 146 ± 49 | 173 ± 73 | 148 ± 59* | (0.250, 0.040, 0.208) |

| Mid-Thigh Fat Area, cm2 | 282 ± 94 | 273 ± 81 | 308 ± 127 | 294 ± 117 | 329 ± 157 | 286 ± 123* | (0.100, 0.004, 0.119) |

| Mid-Thigh Skeletal Muscle, cm2 | 234 ± 40 | 236 ± 35 | 274 ± 66 | 292 ± 57 | 258 ± 43 | 258 ± 38 | (0.520, 0.220, 0.428) |

Two-way, mixed-effects analysis of variance of covariance with repeated measures (ANCOVA) was employed to examine mean differences in pre-to posttraining values, with the baseline values serving as the covariate (see methods for details). For all analyses, linear contrasts of the means were constructed to test our a priori hypotheses. Fisher’s Restricted Least Significant Differences criterion was utilized to maintain the a priori type I error rate of 0.05.

Significantly different from baseline (p <0.05)

Significant treatment effect (post — pre) compared with NOET (p <0.05)

Significant treatment effect (post — pre) compared with LIET (p <0.05)

Data were log transformed to produce symmetric distributions.

Figure 2.

Effects 16 weeks of no exercise training (Control, n = 7), low-intensity exercise training (LIET, n = 11), and high-intensity exercise training (HIET, n = 9) on abdominal subcutaneous abdominal fat (B), visceral fat (A), total mid-thigh skeletal muscle (C) and total mid-thigh fat (D) cross-sectional area. The values shown represent the individual percent change (%Δ values (open-circles), the mean %Δvalues (solid square), the median %Δ values (box-split), the lower (bottom of the box) and upper quartiles (top of the box), and the minimum and maximum %Δvalues (lines) by condition.

Two-way, mixed-effects analysis of variance of covariance with repeated measures (ANCOVA) was employed to examine mean differences in pre- to posttraining values, with the baseline values serving as the covariate (see methods for details). For all analyses, linear contrasts of the means were constructed to test our a priori hypotheses. Fisher’s Restricted Least Significant Differences criterion was utilized to maintain the a priori type I error rate of 0.05.

Cardiorespiratory Fitness

LIET and HIET significantly elevated VO2 Peak (p = 0.047, p = 0.004, respectively; Table 3). The increase in VO2 Peak in the HIET condition exceeded that for Control and LIET conditions (p = 0.016, p = 0.078, respectively; Table 3). VO2 LT was unchanged after training in all three conditions (all p > 0.1; Table 3). LIET and HIET resulted in significant elevations in peak treadmill velocity (p = 0.006, p < 0.001, respectively; Table 3). HIET induced a greater elevation in peak treadmill velocity than Control and LIET (p = 0.005, p = 0.056, respectively; Table 3).

BMR, Physical Activity and Diet

We did not observe any significant changes in the BMR (Table 3) or substrate oxidation assessed using the basal respiratory exchange ratio (data not shown). We also did not observe any significant changes in total physical activity in response to the three treatment conditions (Table 3). A limitation of the present study is that due to incomplete dietary data we were unable to adequately analyze the dietary records for pre- to posttraining changes in caloric intake.

Spearman Correlation Analyses

Pooled Spearman correlation analyses (N = 27) were conducted to examine the relationships among pre- to posttraining changes weight, percent fat, AVF, and the metabolic syndrome parameters. Weight loss was positively associated with reductions in triglycerides (r = 0.56; p = 0.002) and SBP (r = 0.44; p = 0.022). Fat mass loss was also positively associated with (r = 0.49; p = 0.009) triglycerides.

DISCUSSION

Body Composition

Published data on the effect of exercise training intensity on body composition and regional body fat are mixed (4; 15; 17; 27; 36; 41). With regard to total body fat loss, total caloric expenditure appears to be the key factor (4; 15; 17; 37). Slentz et al. (37) reported that low-amount/moderate-intensity and low-amount/vigorous-intensity endurance training (i.e., activity equivalent to ∼12 miles·week-1 of walking or jogging) were equally effective in reducing % body fat, fat mass, waist circumference, and abdominal circumference in previously sedentary, overweight, middle-aged adults. They also reported that high-amount/vigorous intensity endurance training (activity equivalent to ∼20 miles·week-1 of jogging) was more effective in reducing % body fat and fat mass compared to the two low-amount training groups (37). Although the exercise intensity was not equated across training volumes, the authors did effectively demonstrate a dose-response relationship between training volume and amount of weight change using a pooled analysis (37).

Our results suggest that HIET may be an effective stimulus for inducing favorable changes in body composition. Specifically, HIET significantly reduced body weight, BMI, % body fat, fat mass and waist circumference (Table 1). Our results are consistent with those of Tremblay et al. (42) who reported that high-intensity intermittent exercise training induced greater subcutaneous fat loss compared to moderate-intensity exercise training under isocaloric training conditions. Similarly, Tremblay et al. (41), also reported results from the Canadian Fitness Survey that indicated that vigorous-physical activity was associated with lower subcutaneous skinfold thickness, which continued to remain significant after adjusting for total energy expenditure. It should be realized that HIET was likely associated with slightly greater exercise energy expenditure and total energy expenditure than LIET. The kcal per training session was based on total energy expenditure (e.g. 300, 350 or 400 kcal per session) and resting metabolism was part of the total. Therefore on the high intensity exercise days where duration was ∼ 6 min shorter (Table 4), resting metabolism would contribute to a lower fraction of the total energy expenditure. This resulted in an ∼ 400 kcal difference in exercise energy expenditure between the high and low intensity groups over the 16 week time frame(∼ 25 kcal/week). In addition, it is likely that post-exercise oxygen consumption was higher on the HIET days.

In view of previous work and the present findings, an interaction between exercise intensity and training volume may exist with respect to changes in body composition. Further investigations are warranted to examine the interaction between training volume and intensity on changes in body composition.

Regional Body Fat

Exercise training, even in the absence of weight loss, is associated with a significant reduction in AVF (27). Whether intensity of exercise is an important training variable for inducing reductions in AVF is not clear, although data on responses to acute exercise suggest that higher-intensity exercise may be more effective than low-to-moderate-intensity exercise for mobilizing AVF by inducing secretion of lipolytic hormones, facilitating greater post-exercise energy expenditure and fat oxidation, and by favoring a greater negative energy balance (21; 32; 33). Our results indicate that HIET is an effective exercise abdominal subcutaneous fat (-47 cm2 vs. -11 cm2, adjusted for baseline) and AVF (-24 cm2 vs. -7 cm2, adjusted for baseline). Data from Slentz et al. (36), however, suggest that low-amount/moderate-intensity or low-amount/vigorous-intensity exercise training were equally effective in preventing significant increases in AVF associated with continued physical inactivity in sedentary, overweight, middle-aged adults under isocaloric conditions. These authors also reported a significant reduction in AVF in subjects who completed 8 months of high-amount/vigorous-intensity exercise training (activity equivalent to ∼20 miles week-1 of jogging), indicating that training volume may play a critical factor in exercise induced AVF loss (36). However, by not including a high-amount/moderate-intensity exercise training group, the authors eliminated the opportunity to determine whether an interaction between training volume and training intensity exist for AVF loss. The training volume in the present study was equated across training conditions and was similar to the training volume in the high-amount/vigorous-intensity training condition reported by Slentz et al. (36). Taken together, these data suggest that an interaction between training volume and training intensity may exist for AVF loss.

BMR, Physical Activity and Diet

Reported total physical activity and BMR remained unchanged. Unfortunately, due to incomplete dietary data we were unable to adequately analyze changes in caloric intake and composition. Although several studies suggest that some women gain weight (and body fat) in response to exercise training, most of these studies have used low-to-moderate exercise intensities (8; 11). The present data indicate that exercise training above the LT (i.e., HIET) may be an effective exercise intensity for inducing weight loss in obese women. Although not measured, it is also likely that HIET resulted in increased post-exercise energy expenditure which in turn was related to lower body fat deposition (44).

Exercise Adherence

The present results demonstrate that endurance training intensity does not significantly impact exercise adherence. The primary reasons given for missing exercise sessions in the present cohort were related to time conflicts and personal travel. As the mean (and median) exercise adherence was ∼80%, four days of structured endurance training (at ∼1600 kcal/week) appears to be a more realistic goal in this cohort of obese women with the metabolic syndrome. All participants were encouraged to make-up their missed training sessions when possible, and the participants in the HIET condition were encouraged to complete all three HIET sessions per week. Four days per week (at ∼1600 kcal/week) of endurance training would still remain within the current recommendations (19). It is also important to realize that the HIET was a blend of LIET (2 days per week) and HIET (3 days per week) and that participants were allowed to initially complete the HIET sessions in a “interval/intermittent” type fashion. For example, for the first few laps of each training session some subjects would perform one lap at an RPE of 16-17 and the subsequent then a lap at 13-14, with the majority of the laps performed at an RPE ≥ 15. Moreover, the overall mean RPE for each HIET session was ≥ 15. The present results also demonstrate that even very sedentary, unfit, obese women (people) can adhere to a supervised program incorporating HIET.

Cardiorespiratory Fitness

Epidemiological data indicate that elevations in cardiorespiratory fitness (i.e., VO2 Peak) is associated with an attenuation cardiometabolic risk among individuals with the metabolic syndrome (25). It is well established that endurance training intensity is a primary determinant for exercise induced improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness (3). HIET increased VO2 Peak more than LIET (∼14% vs. ∼9%), and this difference approached statistical significance after 16 weeks (Table 1). It is possible that larger intensity-related differences in VO2 Peak enhancement may take longer than 4 months in previously sedentary adults. We previously reported that training-induced elevations in VO2 Peak and VO2 at the LT in response to training at or above the LT were similar across the first four months of training in previously sedentary women (43). However, training above the LT was more effective than training at the LT beyond four months (43).

Metabolic Syndrome Parameters

Despite significant improvements in body composition, including significant reductions in waist circumference and AVF, within the HIET condition the improvement in some cardiometabolic risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome (e.g., increased HDL-C, decreased TG) did not reach statistical significance and did not appear to be related to exercise training intensity. However, the present study was powered for changes in body composition and not for cardiometabolic risk factors. As expected, exercise training induced reductions in resting blood pressure. Typically, training-induced reductions in resting blood pressure are reported to be independent of training intensity (13). The significantly greater reduction in systolic blood pressure after LIET may have been due in part to the higher initial value, as baseline blood pressure appears to be an important factor in the blood pressure response to exercise (13). However, covarying for the baseline systolic blood pressure did not attenuate the effect of LIET on systolic blood pressure.

Spearman Correlation Analyses

Weight loss was associated with reductions in triglycerides and systolic blood pressure, while fat loss was only associated with reductions in triglycerides. Although not statistically significant, AVF loss was associated with the expected reductions in triglycerides. The non-significant associations between AVF loss and the metabolic syndrome components (i.e., fasting glucose, HDL-C, triglycerides, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure) indicates that it might take a greater AVF loss in our abdominally obese cohort to observe significant improvements in these parameters. For example, recent data from Thamer et al. (39) indicated that subjects with high AVF and high liver fat have a reduced chance in profiting from lifestyle intervention and suggested that they may require intensified lifestyle intervention strategies and/or pharmacological approaches to improve the metabolic profile. Moreover, it has been previously reported that individuals with excessive AVF (e.g., > 130 cm2) often develop these cardiometabolic risk factors (9; 10). As the mean baseline AVF cross-sectional area for each exercise condition was substantially elevated (> 153 cm2) and, although reduced as a result of training, were still well above 130 cm2 (>146 cm2). It is possible that greater reductions in AVF may be required in order to observe favorable changes in these metabolic syndrome parameters.

Limitations

We recognize that a potential limitation of the present study is that the subjects in the HIET group tended to have slightly higher levels of AVF at the onset of the study. However, adjusting for baseline levels of AVF did not significantly attenuate the impact that HIET had on AVF. It has been previously reported that the use of single-slice images to measure changes in AVF are less precise than multi-slice images (40) and therefore, may also be a limitation of the present study. However, a more precise measurement of the change in AVF likely would have resulted in narrower 95% confidence intervals and significant between group differences with respect to the change in AVF. Although the present study was initially powered to detect significant changes in the AVF (∼30 cm2) with 12 participants per group, the present study did not achieve this level of recruitment, because the number of drop outs exceeded our original estimation. However, despite this limitation we did observe a statistically significant improvement in body composition (including AVF) within the HIET condition. Finally, due to incomplete dietary data, we were not able to adequately analyze the impact of reduced caloric intake on changes in body composition. It has also been suggested that the use of RPE for exercise prescription may be a limitation. For example, when subjects know they are supposed to exercise at an RPE of 15-17 but they do not want to exercise that vigorously, this is a circumstance that may be prone to inflating a given RPE. However, the training program used did result in differentiated training effects for VO2 peak and peak treadmill velocity. Finally, because of the issues related to statistical power, it is possible that some variables would have reached the level of statistical significance if more subjects had been studied. Thus the non-significant results presented need to be interpreted with caution.

Summary

The results of the present investigation support our primary hypothesis that HIET would be more effective than LIET for altering body composition in obese women with the metabolic syndrome. Further investigations are warranted to determine the impact of training duration, gender, race, age, and menopausal status on modulating the effect that exercise training intensity has on AVF and associated cardiometabolic risk factors.

Acknowledgments

The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM. The present study was funded in part by an NIH grant to the General Clinical Research Center RR MO100847 and NIH training grant 5T32AT00052. The authors have no other financial disclosures to declare. The authors wish to thank the staff of the GCRC at the University of Virginia and all of the subjects who participated enthusiastically in the study. The authors would also like to thank James T. Patrie for useful discussions on statistical considerations.

Grant Support: NIH Grant Numbers RR00847 and T32-AT-00052

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no financial disclosures to declare.

Clinical Trial Number: NCT00350064

References

- 1.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O’Brien WL, Bassett DR, Jr., Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO, Jacobs DR, Jr., Leon AS. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S498–504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome--a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23(5):469–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Sports Medicine . ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 7th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, Pa.: 2006. p. 366. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballor DL, McCarthy JP, Wilterdink EJ. Exercise intensity does not affect the composition of diet- and exercise-induced body mass loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51(2):142–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr DB, Utzschneider KM, Hull RL, Kodama K, Retzlaff BM, Brunzell JD, Shofer JB, Fish BE, Knopp RH, Kahn SE. Intra-abdominal fat is a major determinant of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria for the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2004;53(8):2087–94. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clasey JL, Bouchard C, Wideman L, Kanaley J, Teates CD, Thorner MO, Hartman ML, Weltman A. The influence of anatomical boundaries, age, and sex on the assessment of abdominal visceral fat. Obes Res. 1997;5(5):395–401. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dempster P, Aitkens S. A new air displacement method for the determination of human body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(12):1692–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Despres JP, Bouchard C, Savard R, Tremblay A, Marcotte M, Theriault G. The effect of a 20-week endurance training program on adipose-tissue morphology and lipolysis in men and women. Metabolism. 1984;33(3):235–9. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(84)90043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Despres JP, Lemieux I, Dagenais GR, Cantin B, Lamarche B. HDL-cholesterol as a marker of coronary heart disease risk: the Quebec cardiovascular study. Atherosclerosis. 2000;153(2):263–72. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Després J-P, Moorjani S, Lupien PJ, Tremblay A, Nadeau A, Bouchard C. Regional distribution of body fat, plasma lipoproteins, and cardiovascular disease. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:497–511. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.10.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donnelly JE, Hill JO, Jacobsen DJ, Potteiger J, Sullivan DK, Johnson SL, Heelan K, Hise M, Fennessey PV, Sonko B, Sharp T, Jakicic JM, Blair SN, Tran ZV, Mayo M, Gibson C, Washburn RA. Effects of a 16-month randomized controlled exercise trial on body weight and composition in young, overweight men and women: the Midwest Exercise Trial. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(11):1343–50. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.11.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Facchini FS, Hua N, Abbasi F, Reaven GM. Insulin resistance as a predictor of age- related diseases. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology Metabolism. 2001;86(8):3574–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fagard RH. Exercise characteristics and the blood pressure response to dynamic physical training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(6 Suppl):S484–92. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00018. discussion S93- 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. xix. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, N.J.: 2004. p. 506. (Wiley series in probability and statistics). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaesser GA, Rich RG. Effects of high- and low-intensity exercise training on aerobic capacity and blood lipids. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1984;16(3):269–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giannopoulou I, Ploutz-Snyder LL, Carhart R, Weinstock RS, Fernhall B, Goulopoulou S, Kanaley JA. Exercise is required for visceral fat loss in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(3):1511–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grediagin A, Cody M, Rupp J, Benardot D, Shern R. Exercise intensity does not effect body composition change in untrained, moderately overfat women. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95(6):661–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(95)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr., Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr., Lenfant C. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, Powell KE, Blair SN, Franklin BA, Macera CA, Heath GW, Thompson PD, Bauman A. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1423–34. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hetzler RK, Seip RL, Boutcher SH, Pierce E, Snead D, Weltman A. Effect of exercise modality on ratings of perceived exertion at various lactate concentrations. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991;23(1):88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imbeault P, Saint-Pierre S, Almeras N, Tremblay A. Acute effects of exercise on energy intake and feeding behaviour. Br J Nutr. 1997;77(4):511–21. doi: 10.1079/bjn19970053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irving BA, Weltman JY, Brock DW, Davis CK, Gaesser GA, Weltman A. NIH ImageJ and Slice-O-Matic computed tomography imaging software to quantify soft tissue. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(2):370–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irwin ML, Yasui Y, Ulrich CM, Bowen D, Rudolph RE, Schwartz RS, Yukawa M, Aiello E, Potter JD, McTiernan A. Effect of exercise on total and intra-abdominal body fat in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2003;289(3):323–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakicic JM, Donnelly JE, Pronk NP, Jawad AF, Jacobsen DJ. Prescription of exercise intensity for the obese patient: the relationship between heart rate, VO2 and perceived exertion. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19(6):382–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katzmarzyk PT, Church TS, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness attenuates the effects of the metabolic syndrome on all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(10):1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohl HW, Blair SN, Paffenbarger RS, Jr., Macera CA, Kronenfeld JJ. A mail survey of physical activity habits as related to measured physical fitness. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127(6):1228–39. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee S, Kuk JL, Davidson LE, Hudson R, Kilpatrick K, Graham TE, Ross R. Exercise without weight loss is an effective strategy for obesity reduction in obese individuals with and without Type 2 diabetes. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99(3):1220–5. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00053.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. vi. Human Kinetics Books; Champaign, IL: 1988. p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitsiopoulos N, Baumgartner RN, Heymsfield SB, Lyons W, Gallagher D, Ross R. Cadaver validation of skeletal muscle measurement by magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85(1):115–22. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicklas BJ, Penninx BW, Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, Kanaya AM, Pahor M, Jingzhong D, Harris TB. Association of visceral adipose tissue with incident myocardial infarction in older men and women: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(8):741–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Leary VB, Marchetti CM, Krishnan RK, Stetzer BP, Gonzalez F, Kirwan JP. Exercise-induced reversal of insulin resistance in obese elderly is associated with reduced visceral fat. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100(5):1584–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01336.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pritzlaff CJ, Wideman L, Blumer J, Jensen M, Abbott RD, Gaesser GA, Veldhuis JD, Weltman A. Catecholamine release, growth hormone secretion, and energy expenditure during exercise vs. recovery in men. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89(3):937–46. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pritzlaff CJ, Wideman L, Weltman JY, Abbott RD, Gutgesell ME, Hartman ML, Veldhuis JD, Weltman A. Impact of acute exercise intensity on pulsatile growth hormone release in men. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87(2):498–504. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.2.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD, Fortmann SP, Rogers T, Blair SN, Paffenbarger RS., Jr Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five-City Project. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121(1):91–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seip RL, Snead D, Pierce EF, Stein P, Weltman A. Perceptual responses and blood lactate concentration: effect of training state. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991;23(1):80–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slentz CA, Aiken LB, Houmard JA, Bales CW, Johnson JL, Tanner CJ, Duscha BD, Kraus WE. Inactivity, exercise, and visceral fat. STRRIDE: a randomized, controlled study of exercise intensity and amount. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99(4):1613–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00124.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slentz CA, Duscha BD, Johnson JL, Ketchum K, Aiken LB, Samsa GP, Houmard JA, Bales CW, Kraus WE. Effects of the amount of exercise on body weight, body composition, and measures of central obesity: STRRIDE--a randomized controlled study. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(1):31–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stoudemire NM, Wideman L, Pass KA, McGinnes CL, Gaesser GA, Weltman A. The validity of regulating blood lactate concentration during running by ratings of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28(4):490–5. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199604000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thamer C, Machann J, Stefan N, Haap M, Schafer S, Brenner S, Kantartzis K, Claussen C, Schick F, Haring H, Fritsche A. High visceral fat mass and high liver fat are associated with resistance to lifestyle intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(2):531–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas EL, Bell JD. Influence of undersampling on magnetic resonance imaging measurements of intra-abdominal adipose tissue. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(2):211–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.802229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tremblay A, Despres JP, Leblanc C, Craig CL, Ferris B, Stephens T, Bouchard C. Effect of intensity of physical activity on body fatness and fat distribution. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51(2):153–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tremblay A, Simoneau JA, Bouchard C. Impact of exercise intensity on body fatness and skeletal muscel metabolism. Metabolism. 1994;43:814–8. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(94)90259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weltman A, Seip RL, Snead D, Weltman JY, Haskvitz EM, Evans WS, Veldhuis JD, Rogol AD. Exercise training at and above the lactate threshold in previously untrained women. Int J Sports Med. 1992;13(3):257–63. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshioka M, Doucet E, St-Pierre S, Almeras N, Richard D, Labrie A, Despres JP, Bouchard C, Tremblay A. Impact of high-intensity exercise on energy expenditure, lipid oxidation and body fatness. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(3):332–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]