Abstract

Background

Nitric oxide is known to be essential for early anesthetic (APC) and ischemic (IPC) preconditioning of myocardium. Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that Hsp90-eNOS interactions modulate APC and IPC.

Methods

Myocardial infarct size was measured in rabbits after coronary occlusion and reperfusion in the absence or presence of preconditioning with 30 min of isoflurane (APC) or 5 min of coronary artery occlusion (IPC), and with or without pre-treatment with geldanamycin or radicicol, two chemically distinct Hsp90 inhibitors, or NG-nitro-L-arginine methylester, a non-specific NOS inhibitor. Isoflurane-dependent nitric oxide production was measured (ozone chemiluminescence) in human coronary artery endothelial cells or mouse cardiomyocytes, in the absence or presence of Hsp90 inhibitors or NG-nitro-L-arginine methylester. Interactions between Hsp90 and eNOS, and eNOS activation were assessed with immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting, and confocal microscopy.

Results

APC and IPC decreased infarct size (50% and 59%, respectively) and this action was abolished by Hsp90 inhibitors. NG-nitro-L-arginine methylester blocked APC but not IPC. Isoflurane increased nitric oxide production in human coronary artery endothelial cells, concomitantly with an increase in Hsp90-eNOS interaction (immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting, and immunohistochemistry). Pretreatment with Hsp90 inhibitors abolished isoflurane-dependent nitric oxide production and decreased Hsp90-eNOS interactions. Isoflurane did not increase nitric oxide production in mouse cardiomyocytes and eNOS was below the level of detection.

Conclusion

The results indicate that Hsp90 plays a critical role in mediating APC and IPC through protein-protein interactions, and suggest that endothelial cells are important contributors to nitric oxide-mediated signalling during APC.

Introduction

Growing evidence indicates that heat shock protein (Hsp) 90 regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) phosphorylation (Serine 1177)1 and modulates subsequent nitric oxide production.1–5 Endothelial NOS activity is regulated by protein binding partners such as Hsp90,2,6,7 and the association between Hsp90 and eNOS maintains the enzyme in a coupled state in which eNOS produces nitric oxide and not superoxide anion.6 Activation of eNOS is associated with phosphorylation of Serine 1177, and nitric oxide production is proportional to the extent of eNOS phosphorylation.8 Certain pathophysiological stimuli, such as hypoxia or angiotensin-1, have been demonstrated to enhance Hsp90-eNOS association and eNOS phosphorylation in porcine coronary artery endothelial cells, concomitantly with increased nitric oxide release.3,4 This action was blocked by specific Hsp90 inhibitors.3,4,7

Early myocardial preconditioning is a cellular adaptive phenomenon whereby brief episodes of myocardial ischemia interspersed with reperfusion (ischemic preconditioning; IPC) or exposure to certain pharmacological agents, such as volatile anesthetics (anesthetic preconditioning; APC), decreases the extent of ischemia and reperfusion injury after a subsequent prolonged period of coronary artery occlusion. IPC and APC activate phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase which stimulates extracellular signal regulated kinase ½ and downstream serine/threonine protein kinase Akt that contributes to the activation of eNOS through phosphorylation of Serine 1177.9,10 The abolition of eNOS activity blocks the cardioprotective effect of upstream proteins such extracellular signal regulated kinase ½ or 70-kDA ribosomal protein s6 kinase activated by isoflurane.11 Nitric oxide has previously been demonstrated to enhance adenosine triphosphate regulated potassium channel activation that mediates cardioprotection,10,12–14 and this molecule has been suggested to be a trigger of IPC15 and APC.16 At least three NOS isoforms contribute to nitric oxide production in the heart, although, eNOS appears to play a major role in early myocardial preconditioning.12,14 Unlike eNOS the involvement of Hsp90 in APC or IPC has not been elucidated. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that Hsp90 and eNOS are critical triggers of APC and IPC by activating nitric oxide-dependent cardioprotective signaling.

Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures and protocols used in this investigation were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin (Milwaukee, WI). Furthermore, all conformed to the Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals of the American Physiologic Society and were in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

In Vivo Myocardial Infarction Model

Male New Zealand white rabbits were anesthetized with intravenous sodium pentobarbital (30 mg•kg−1) and instrumented as previously described.17 Briefly, a tracheotomy was performed and rabbits were ventilated with positive pressure using an air-oxygen mixture (30% fractional inspired oxygen concentration). Arterial blood gas tensions and acid-base status were maintained within a normal physiological range by adjusting the respiratory rate or tidal volume throughout the experiment. Heparin-filled catheters were positioned in the right carotid artery and the left jugular vein for continuous measurement of arterial blood pressure, and fluid and drug administration (0.9% saline; 15 ml•kg−1•h−1), respectively. After thoracotomy, a silk ligature was placed around the left anterior descending coronary artery approximately halfway between the base and the apex for the production of coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion. Coronary artery occlusion was verified by the presence of epicardial cyanosis and regional dyskinesia in the ischemic zone, and reperfusion was confirmed by observing an epicardial hyperemic response.

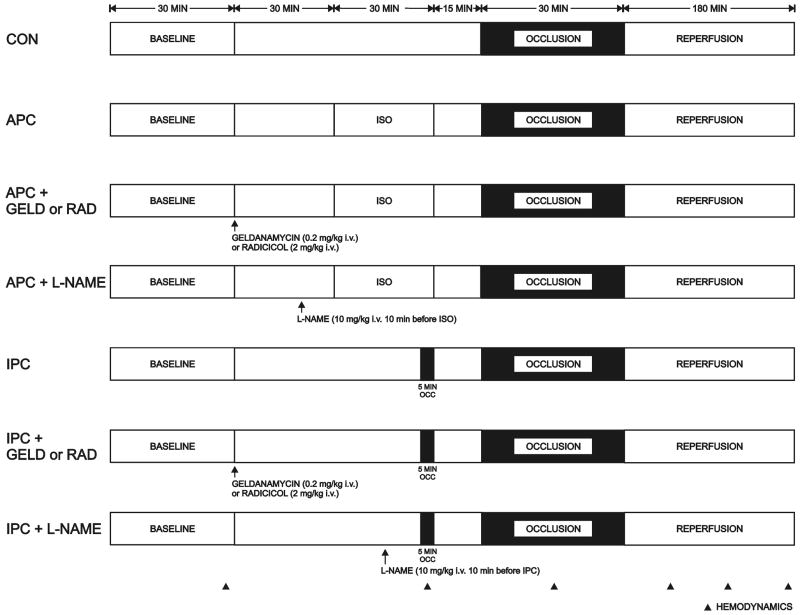

The experimental protocol is illustrated in Figure 1. All rabbits underwent a 30 minutes left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion followed by 3 hours of reperfusion. Rabbits were randomly assigned to receive 30 minutes of isoflurane 2.1% (1 minimal alveolar concentration; APC) or a single 5 minute left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion (IPC) ending 15 minutes prior to prolonged coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion, in the presence or absence of pre-treatment with intravenous 0.9% saline (control), geldanamycin (0.2 mg• kg−1, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO)18 or radicicol (2 mg•kg−1, A.G. Scientific, San Diego, CA),18 two chemically distinct specific Hsp90 inhibitors or N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME, 10 mg•kg−1, Sigma-Aldrich),19 a non selective NOS inhibitor.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration depicting the experimental protocols used to determine myocardial infarct size in rabbits in vivo. Additional experiments were completed with geldanamycin, radicicol or L-NAME alone.

CON= control; APC= anesthetic preconditioning; ISO= isoflurane; GELD= geldanamycin; RAD= radicicol; L-NAME = N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; IPC= ischemic preconditioning

Myocardial infarct size was measured as previously described20 and expressed as a percentage of the left ventricular area at risk. Rabbits that developed intractable ventricular fibrillation and those with an area at risk less than 15% of total left ventricular mass were excluded from subsequent analysis.

Human Coronary Artery Endothelial Cells and HL-1 Cardiomyocytes

Human coronary artery endothelial cells isolated from healthy coronary arteries (Cells Applications, San Diego, CA) were cultured without cryopreservation, propagated to 5th passage in growth medium (Cells Applications) and used for experiments between the 4th and the 5th passage. HL-1 cardiomyocytes, derived from the AT-1 mouse atrial myocyte immortalized lineage (a gift from William C. Claycomb, Ph.D., Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA) were maintained according to described protocols.21 Cells where used for experiments when approximately 70 to 80% confluent. Human coronary artery endothelial cells and HL-1 cardiomyocytes were seeded on plastic dishes (100 mm) and pre-treated at 37°C in growth medium with geldanamycin (17.8 μM), radicicol (20 μM) for 3 hours or N-G-mono-methyl-L-arginine monoacetate (L-NMMA, 1 mM, Sigma-Aldrich) for 12 hours6,18 before exposure to isoflurane or air (Control). Cell growth medium was replaced with PSS buffer (NaCl 137.0 mM, Kcl 5.4 mM, MgCl2 1.0 mM, CaCl2 2.0 mM, HEPES 10.0 mM, D-Glucose 5.0 mM, pH 7.40) during ozone chemiluminescence experiments because growth medium contains nitrite that would increase the background signal. Cells were exposed to isoflurane (0.42 mM; 1 minimal alveolar concentration), continuously monitored by a gas analyzer (POET IQ, Critcare System, Waukesha, WI), at continuous air flow (0.7 l•min−1) in a specific incubator chamber (Billups-Rozenburg, Del-Mar, CA) maintained at 37°C. Because gas flow can induce a shear-stress-dependent nitric oxide release by itself,22 the control group was exposed to air alone at the same flow rate.

Ozone Chemiluminescence

Nitrite concentration corresponding to the stable breakdown product of nitric oxide in aqueous solution was assessed by ozone chemiluminescence. Previous evidence suggests that nitric oxide release in response to stimuli in coronary endothelial cells peaks at 60 minutes.3 Therefore, nitric oxide measurements were performed 60 minutes after isoflurane exposure. Samples (20μl) were refluxed in glacial acetic acid containing sodium iodide and nitrite quantified in a nitric oxide chemiluminescence analyzer (Sievers Instruments, Boulder, CO) as previously described.23 Nitrite concentrations were calculated after subtraction of background levels and normalized to protein content (Bradford method).

Immunoblotting and Co-Immunoprecipitation

Human coronary artery endothelial cells were lysed in 500 μl of lysis buffer (20.0 mM MOPS, 2.0 mM EGTA, 5.0 mM EDTA, protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich), phosphatase inhibitors cocktail (1:100; Calbiochem, San Diego, MO), 0.5% detergent (Nonidet™ P-40 detergent pH 7.4, Sigma-Aldrich) 20 minutes after the beginning of isoflurane exposure, because this time period corresponds to the peak of eNOS phosphorylation in coronary endothelial cells in response to various stimuli.3,4 Fifteen to 25 μg of proteins were loaded on to precast gel 7.5% tris-HCl gels (Criterion, BioRad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. After blocking the membranes in 5% milk in TBS, immunoblots were performed with rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-eNOS (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-eNOS (1:5,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Delaware, CA), mouse monoclonal anti-Hsp90 (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) and were incubated overnight at 4°C. The membrane was then washed and incubated with secondary antibodies horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG for eNOS (1:10,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), goat anti-rabbit for phospho-eNOS (1:10,000; Bio-Rad) and goat anti-mouse for Hsp90 (1:8,000; Bio-Rad). Co-immunoprecipitation was performed by incubating the cell lysates (200 μg) with eNOS monoclonal antibody (2 μg.mg−1 of total cell protein) for 16 h at 4°C, followed by 2 hours incubation with a 1:1 protein A-to-protein G ratio of sepharose leads. After centrifugation, the immunoprecipitates were washed in PBS-T (Sigma-Aldrich), resuspended in Laenmli buffer, boiled for 5 min, loaded on to SDS-PAGE (Sigma-Aldrich) 7.5% gels, and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The primary antibody used for immunoblotting was anti-eNOS (1:5,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) while secondary was anti-Hsp90 (1:8,000; Bio-Rad). The membranes were developed using the ECLplus Western blot chemiluminescence detection reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and densitometric analysis was carried out by using image acquisition and analysis software (Scion Image, Frederick, Maryland).

Confocal Microscopy

To visualize co-localization of Hsp90 and eNOS, human coronary artery endothelial cells were cultured on gelatin-coated slides, as previously described.19 After 60 minutes of isoflurane exposure, human coronary artery endothelial cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.5% TritonX-100 (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C with primary monoclonal antibody anti-eNOS (1:100; Biomol International, Plymouth, PA) in PBS. Incubations with corresponding biotinylated secondary antibodies Alexa 488 conjugated (1:1,000; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) were conducted for 30 minutes at 37°C. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C with monoclonal antibody anti-Hsp90 (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). Incubations with corresponding biotinylated secondary antibodies Alexa 546 conjugated (1:1,000; Invitrogen) were conducted for 30 minutes at 37°C followed by 1:1000 TO-PRO-3 (nuclear stain; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 5 minutes at room temperature and washed again with PBS. Images were visualized using confocal microscopy (Nikon Eclipse TE 200-U microscope with EZ C1 laser scanning software, Melville, NY) using excitation wavelengths of 488/546/663 nm and emission wavelengths of greater than 520/578/661 nm for eNOS, HSP90, TO-PRO-3 respectively. The number of double-stained cells indicating co-localization of Hsp90 and eNOS were counted and expressed as a percentage of the total cell count.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

Superoxide radical anion measurements have been performed using hydroethidine probe and high performance liquid chromatography-based quantitation of 2-hydroxyethidium in cell lysates as described elsewhere.24 Briefly, hydroethidine (10 μM, Sigma-Aldrich) was added immediately before isoflurane exposure. After 60 minutes of isoflurane exposure, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS, Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were pelleted, then lysed in ice-cold Dulbecco’s PBS containing 0.1% Triton X 100, and lysate aliquots mixed (1:1) with 0.2 M perchloric acid in methanol. After initial centrifugation (30 minutes × 20,000 g at 4 °C) the supernatants were mixed (1:1) with 1 M potassium phosphate buffer pH 2.6 and centrifuged again (15 minutes × 20,000 g at 4 °C). The supernatants were obtained for high-performance liquid chromatography analysis. The quantitation of hydroethidine and its oxidation products was carried out via high-performance liquid chromatography (ESA, Chelmsford, MA) with electrochemical detection using Synergi Polar RP column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 4 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). The results were normalized to protein concentration in the lysates, as analyzed using Bradford reagent. All the reagents, additions and incubations were protected from exposure to light.

Statistics

Data were expressed as mean±SD. Comparison of two means was performed using the Student’s-t-test. Comparison of several means was performed using one-way (1 factor tested) or two-way (2 factors tested) analysis of variance, when appropriate, and the post hoc test used was the Newman-Keuls test. Hemodynamic data were analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance. All P values were two-tailed and a P value < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using NCSS 2007 software (Statistical Solutions Ltd., Cork, Ireland).

Results

Involvement of Hsp90 and eNOS in APC and IPC in vivo

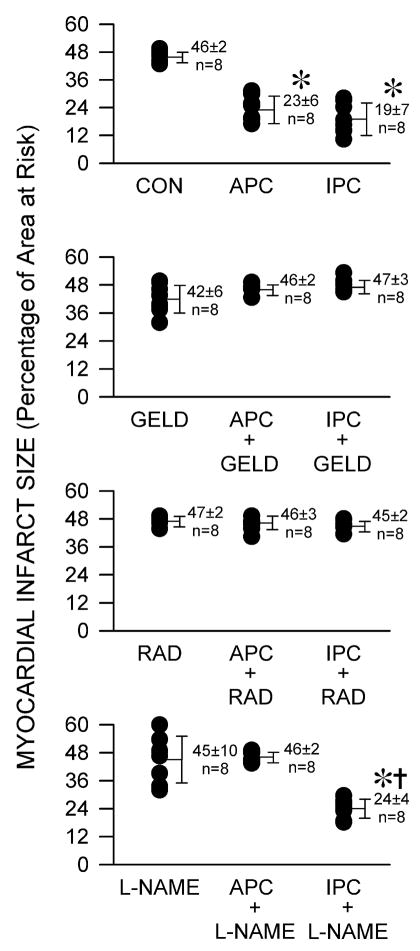

One hundred and four rabbits were instrumented to obtain 96 successful experiments in which infarct size was measured. Eight rabbits were excluded because intractable ventricular fibrillation occurred during coronary artery occlusion (2 in control, 2 in geldanamycin, 3 in radicicol and 1 in L-NAME groups, respectively). Arterial blood gas tensions were maintained within the physiologic range in each group (data not shown). Systemic hemodynamics were similar at baseline among groups. L-NAME caused a brief increase in mean arterial pressure and decrease in heart rate (table 1) compared to the control experiments. Left ventricular mass, area at risk mass, and the ratio of area at risk to left ventricular mass were not different between groups (table 2). APC and IPC decreased myocardial infarct size (23±6 and 19±7% of the left ventricular area at risk, respectively) compared with control experiments (46±2%, P<0.05) (fig. 2). Geldanamycin, radicicol, or L-NAME alone did not affect infarct size (42±6, 47±2, and 45±10%, respectively), but geldanamycin and radicicol abolished APC (46±2 and 46±3%, respectively) and IPC (47±3 and 45±2%, respectively). L-NAME prevented infarct size reduction with APC (46±2%) but not IPC (24±4%).

Table 1.

Hemodynamics

| Reperfusion (min) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Intervention | Occlusion | 60 | 120 | 180 | |

| HR (min−1) | ||||||

| CON | 256±37 | 258±30 | 251±30 | 233±20 | 227±21 | 219±25* |

| APC | 259±26 | 261±22 | 240±25 | 232±27 | 226±31 | 223±34* |

| IPC | 255±18 | 237±17 | 246±21 | 223±20* | 211±28* | 197±23* |

| GELD | 263±24 | 245±22 | 230±25* | 229±21* | 212±22* | 206±26* |

| APC + GELD | 246±23 | 241±19 | 225±12 | 213±14* | 203±15* | 201±16* |

| IPC + GELD | 251±17 | 238±28 | 229±35 | 223±27 | 211±31* | 199±26* |

| RAD | 251±23 | 233±18 | 234±29 | 233±27 | 223±23 | 218±21 |

| APC + RAD | 245±27 | 245±24 | 248±19 | 239±27 | 226±22 | 219±23 |

| IPC + RAD | 253±26 | 233±22 | 241±22 | 223±23* | 213±22* | 212±23* |

| L-NAME | 246±23 | 206±22*† | 213±19* | 188±26*† | 186±17* | 187±13* |

| APC + L-NAME | 250±18 | 219±25*† | 223±21 | 222±21‡ | 220±21 | 215±23* |

| IPC + L-NAME | 259±22 | 229±15 | 231±27 | 226±41 | 212±44* | 200±33* |

| MAP (mmHg) | ||||||

| CON | 74±7 | 70±5 | 59±6* | 60±10* | 62±11* | 63±10 |

| APC | 78±14 | 60±13 | 67±15 | 69±17 | 68±13 | 69±14 |

| IPC | 76±7 | 64±9 | 61±7* | 65±11 | 70±8 | 70±14 |

| GELD | 72±12 | 74±5 | 60±10* | 64±8 | 64±8 | 63±8 |

| APC + GELD | 60±7 | 61±13 | 53±6 | 53±6 | 56±7 | 56±6 |

| IPC + GELD | 69±8 | 65±8 | 61±16 | 60±7 | 59±9 | 64±12 |

| RAD | 60±5 | 67±13 | 56±15 | 58±10 | 55±11 | 56±11 |

| APC + RAD | 71±17 | 84±14‡ | 68±12 | 62±8* | 60±10* | 63±10* |

| IPC + RAD | 69±16 | 76±12 | 61±8 | 61±10 | 64±6 | 63±6 |

| L-NAME | 81±8 | 88±14† | 62±20 | 64±17 | 63±13 | 69±13 |

| APC + L-NAME | 65±10 | 54±20‡ | 63±5‡ | 55±15 | 65±10 | 59±11 |

| IPC + L-NAME | 66±6 | 75±14‡ | 69±17‡ | 69±20 | 75±18 | 78±17 |

Data are mean±SD; n=8 per group.

:P<0.05 vs baseline.

P<0.05 vs corresponding control.

P<0.05 vs corresponding drug alone (GELD, RAD, L-NAME).

Abbreviations: APC = anesthetic preconditioning (isoflurane, 1 minimal alveolar concentration); CON= control ; GELD = geldanamycin ; HR = heart rate ; IPC = ischemic preconditioning ; L-NAME = N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester ; MAP = mean arterial pressure ; RAD = radicicol.

Table 2.

Left Ventricular Area at Risk

| Body Weight (g) | LV (g) | AAR (g) | AAR/LV (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | 2367±310 | 3.35±0.29 | 1.41±0.18 | 42±5 |

| APC | 2534±422 | 3.07±0.39 | 1.09±0.11 | 36±5 |

| IPC | 2555±211 | 3.16±0.59 | 1.16±0.41 | 36±9 |

| GELD | 2504±217 | 3.14±0.36 | 1.11±0.16 | 36±7 |

| APC + GELD | 2210±97 | 3.28±0.32 | 1.44±0.23 | 44±4 |

| IPC + GELD | 2500±120 | 3.60±0.51 | 1.36±0.38 | 37±8 |

| RAD | 2185±57 | 3.12±0.25 | 1.39±0.15 | 44±3 |

| APC + RAD | 2160±106 | 3.22±0.29 | 1.32±0.23 | 41±5 |

| IPC + RAD | 2569±169† | 3.80±0.49 | 1.46±0.25 | 38.5±4 |

| L-NAME | 2749±147* | 3.14±0.66 | 1.24±0.41 | 39±8 |

| APC + L-NAME | 2288±113† | 3.43±0.35 | 1.37±0.23 | 40±5 |

| IPC + L-NAME | 2238±169† | 3.15±0.18 | 1.11±0.23 | 35±6 |

Data are mean±SD, n=8 per group.

P<0.05 vs Control;

P<0.05 vs corresponding drug alone (GELD, RAD, L-NAME).

Abbreviations: AAR = area at risk ; APC = anesthetic preconditioning (isoflurane, 1 minimal alveolar concentration); CON= control ; GELD = geldanamycin ; IPC = ischemic preconditioning ; L-NAME = N-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester ; LV = left ventricle ; RAD = radicicol.

Figure 2.

Myocardial infarct size depicted as a percentage of left ventricular area at risk in rabbits in the absence (CON) or presence of anesthetic (APC) or ischemic preconditioning (IPC), and in the presence or absence of pre-treatment with geldanamycin (GELD, 0.2 mg.kg−1), radicicol (RAD, 2 mg.kg−1) or N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME, 10 mg.kg−1). Each point represents a single experiment. Data are mean±SD; *: P<0.05 vs CON; †: P<0.05 vs L-NAME alone. n=8/group

Isoflurane-Dependent Nitric Oxide Production in Human Coronary Artery Endothelial Cells and HL-1 Cardiomyocytes

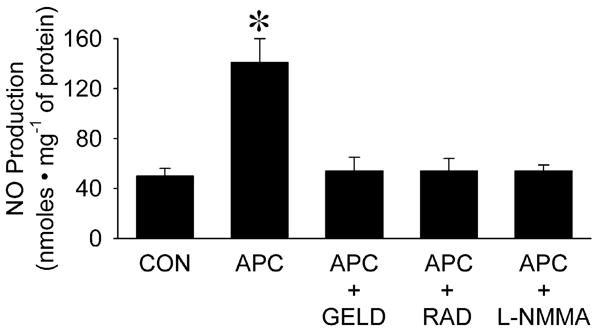

Isoflurane significantly increased nitric oxide production in human coronary artery endothelial cells compared with control experiments (141±19 vs 50±6 nmoles•mg−1 of protein, respectively; P<0.05; fig. 3). Pre-treatment with geldanamycin, radicicol, and N-G-mono-methyl-L-arginine monoacetate abolished isoflurane-dependent nitric oxide production. In contrast, isoflurane did not increase nitric oxide production in HL-1 cardiomyocytes compared to control (190±28 vs 181±27 nmoles mg−1 of protein, respectively; not significant).

Figure 3.

Effect of isoflurane (APC, 0.42 mM or 1 Minimal Alveolar Concentration) on nitric oxide (NO) production compared to control experiments in the absence of volatile anesthetic (CON) in human coronary artery endothelial cells with or without pre-treatment with geldanamycin (GELD, 17.8 μM), radicicol (RAD, 20 μM) or N-G-mono-methyl-L-arginine monoacetate (L-NMMA 1mM).

Data are mean±SD; *: P<0.05 vs CON. n=6 per group.

Hsp90/eNOS Association and eNOS Activation in Human Coronary Artery Endothelial Cells and HL-1 Cardiomyocytes

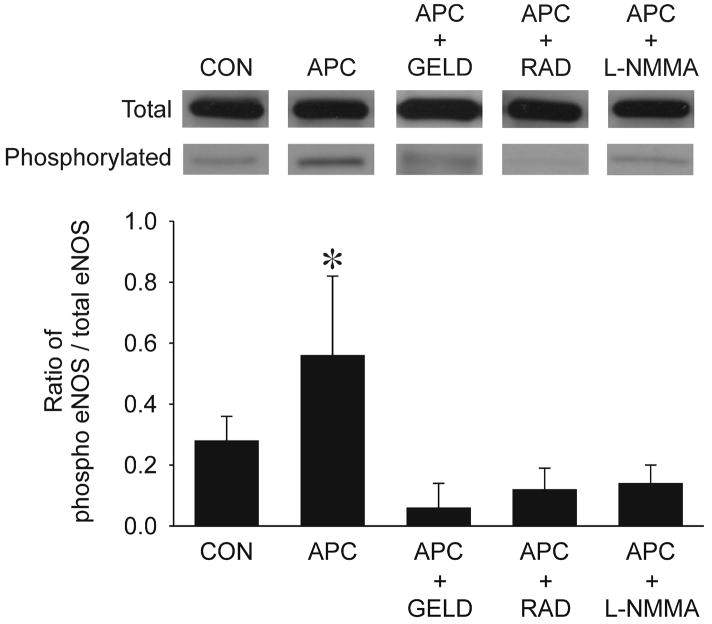

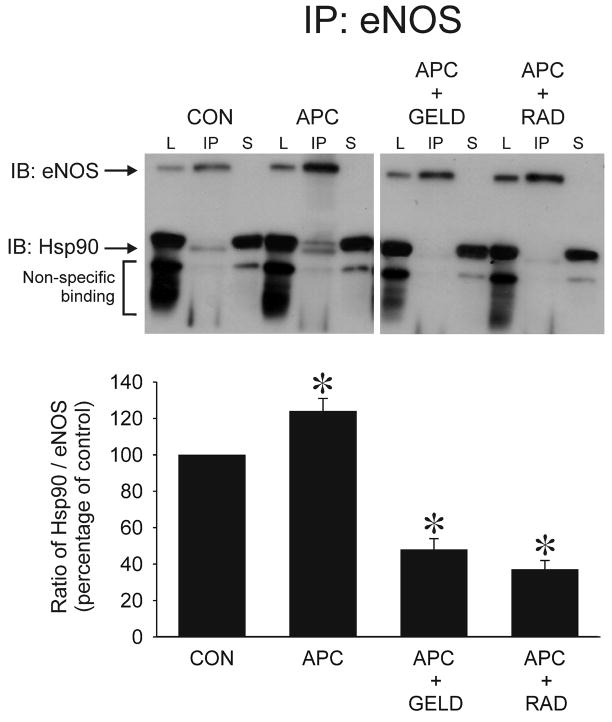

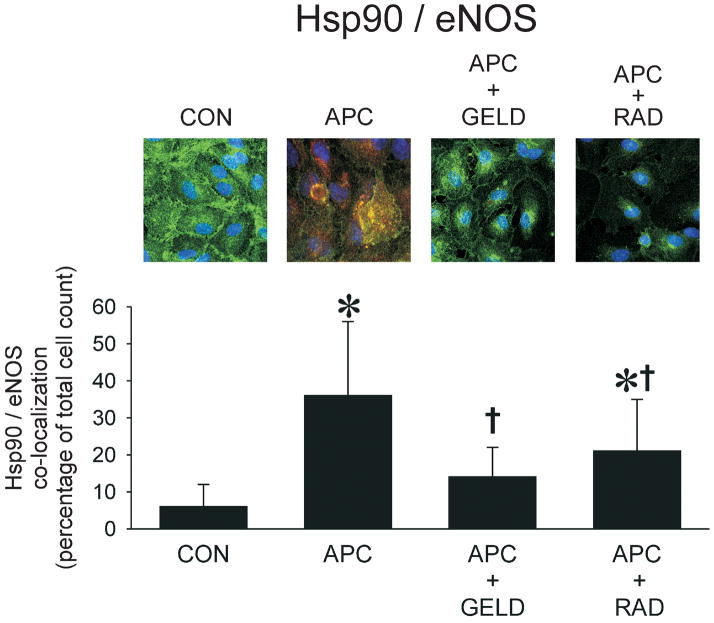

Isoflurane increased the ratio of phospho-eNOS to total eNOS by 2-fold (0.56±0.26 vs 0.28±0.08 in isoflurane vs. control cells, respectively) (fig. 4), and this occurred concomitantly with increased association between Hsp90 and total eNOS as evaluated with immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting (fig. 5) and colocalization assessed by confocal microscopy (fig. 6). Pretreatment with geldanamycin, radicicol, and N-G-mono-methyl-L-arginine monoacetate abolished isoflurane-induced eNOS activation (phospho-eNOS to total eNOS). In HL-1 cardiomyocytes, total eNOS and phospho-eNOS were below detection levels of Western blot analysis (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Representative Western Blot of total and phosphorylated eNOS in human coronary artery endothelial cells exposed to isoflurane (APC, 0.42 mM or 1 Minimal Alveolar Concentration) compared to control (CON) experiments in the absence of volatile anesthetic with or without pre-treatment with geldanamycin (GELD, 17.8 μM), radicicol (RAD, 20 μM) or N-G-mono-methyl-L-arginine monoacetate (L-NMMA, 1mM). Histograms show the ratio of phospho- to total-eNOS in each group.

Data are mean±SD; *: P<0.05) vs CON. n=6 per group.

Figure 5.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) of eNOS and immunoblotting (IB) for eNOS and Hsp90 in human coronary artery endothelial cells exposed to isoflurane (APC, 0.42 mM or 1 Minimal Alveolar Concentration) compared to control experiments (CON) with or without pre-treatment with geldanamycin (GELD, 17.8 μM) or radicicol (RAD, 20 μM). Histograms show the ratio of Hsp90/eNOS in each group. eNOS and hsp90 bands are indicated by arrows. Immunoreactive bands that appear below Hsp90 indicate non-specific binding and were not included in the analysis. Lysate (L) represents total protein before immunoprecipitation. Supernatant (S) represents protein after immunoprecipitation of eNOS. Data are mean±SD; *: P<0.05 vs CON. n= 5 per group.

Figure 6.

Co-localization of eNOS with Hsp90 in human coronary artery endothelial cells exposed to isoflurane (APC, 0.42 mM or 1 Minimal Alveolar Concentration) compared to control experiments (CON) with or without pre-treatment with geldanamycin (GELD, 17.8 μM) or radicicol (RAD, 20 μM). The eNOS/Hsp90 co-localization is demonstrated by yellow staining

Data are mean±SD; *: P<0.05 vs CON. (11–18 fields per group).

Superoxide Anion Production by Isoflurane

Superoxide anion production in human coronary artery endothelial cells was not altered in control experiments compared to isoflurane treatment (0.14 ± 0.08 vs 0.16 ± 0.07 nmoles.mg−1 of protein, respectively; n=13 in each group; not significant).

Discussion

The present results demonstrate the importance of Hsp90 as a modulator of eNOS in APC and IPC in vivo. Isoflurane-preconditioning and IPC significantly decreased myocardial infarct size compared to control experiments, and this protection was abolished by the specific Hsp90 inhibitors, geldanamycin or radicicol. The findings further indicate that Hsp90 association with eNOS is increased by isoflurane in human coronary artery endothelial cells and that enhanced protein-protein interactions contribute to eNOS activation and increased nitric oxide production during APC.

A growing body of evidence implicates eNOS-derived nitric oxide as a critical component of APC signal transduction. We have previously demonstrated that the non-selective NOS inhibitor L-NAME blocked the trigger and mediator phase of delayed APC, whereas specific inhibitors of inducible NOS or neuronal NOS had no effect.19 Endothelial NOS expression (message and protein) was increased immediately and 24 hours after exposure to isoflurane19 and post-conditioning with isoflurane was mediated through eNOS-sensitive regulation of the pro-survival phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase- serine/threonine protein kinase Akt signaling cascade.11 APC with the volatile anesthetic desflurane was also shown to be mediated by eNOS derived nitric oxide.25 APC increased eNOS activity measured in left ventricular myocardium and inhibition of eNOS abolished infarct size reduction when a NOS inhibitor was administered either before or after desflurane.

The current results confirm and extend these previous findings and indicate that APC is critically dependent on both eNOS and Hsp90. Hsp90 is an important physiological regulator of eNOS, and modulation of APC or IPC by Hsp90 has not been previously elucidated. Hsp90 is a highly conserved, mostly cytosolic, protein expressed in all eukaryotic cells26, and is likely to modulate APC and IPC through an evolutionary conserved cellular response.27 This highly abundant protein is a molecular chaperone involved in protein folding and maturation. Recent evidence indicates that Hsp90 has an integral role in cell signal transduction pathways, and its critical importance in the cell is illustrated by the lethality of its homozygous disruption in Drosophila.28 Hsp90 is a physiologic binding partner and regulator of eNOS,29,30 and impairment of eNOS/Hsp90 interactions disrupts nitric oxide-dependent signaling. Endothelial NOS and Hsp90 form complexes in endothelial and smooth muscle cells in response to a variety of eNOS-activating stimuli. This action enhances phosphorylation of eNOS by serine/threonine protein kinase Akt,31 increases nitric oxide release,2 and facilitates cyclic guanosine monophosphate production.26 In contrast, specific inhibitors of Hsp90, such as geldanamycin and radicicol, affect the conformational state of Hsp90 by binding to its unique adenosine triphosphate binding site32 and prevent agonist-induced eNOS-Hsp90- serine/threonine protein kinase Akt association and eNOS phosphorylation.31

Hsp90/eNOS association may be of importance in ischemic myocardium. Chronic hypoxia increases resistance to myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury through a nitric oxide-mediated mechanism. This protection is dependent on enhancement of Hsp90/eNOS association and increased nitric oxide production that is blocked by geldanamycin.7 Hsp90 appears to confer a benefit in chronically hypoxic myocardium by promoting nitric oxide generation and limiting superoxide anion production.7 Targeted overexpression of Hsp90 in myocardium reduces infarct size and enhances the association between Hsp90, eNOS and Akt, resulting in increased phosphorylation of eNOS (at Serine 1177).1 In contrast to these beneficial effects, disrupting the interactions between Hsp90 and eNOS in endothelial cells uncouples enzyme activity. As a result of eNOS uncoupling, the enzyme produces superoxide anion and not nitric oxide, and increased superoxide anion production is inhibitable with L-NAME.6,18,33

The present results demonstrate that Hsp90 is a crucial element in IPC and APC in vivo. Furthermore, experiments conducted in human coronary artery endothelial cells show that isoflurane increases eNOS activity, and that this action is dependent on enhanced association between Hsp90 and eNOS as demonstrated with co-immunoprecipitation and immunohistochemistry. In contrast, isoflurane failed to increase eNOS activity or nitric oxide production in cardiomyocytes. While isoflurane increased nitric oxide concentration in human coronary artery endothelial cells, the concentration of superoxide anion was unaltered. The function of eNOS to generate nitric oxide or superoxide anion is thought to be regulated by site-specific phosphorylation,34 tetrahydrobiopterin concentrations35 and Hsp90.6 Isoflurane did not change superoxide anion concentrations under baseline conditions, but it is possible that isoflurane might decrease superoxide generation under conditions where eNOS is uncoupled (e.g. during hyperglycemia), and in a manner that is Hsp90-dependent. This hypothesis remains to be tested, however. Isoflurane has been shown to increase the production of signaling reactive oxygen species from mitochondria of cardiomyocytes.36 In contrast, isoflurane had no effect on superoxide anion production from endothelial cells. Thus, it is unlikely that endothelial cells are a source of signaling reactive oxygen species during APC.

The role of eNOS during classical IPC is controversial.14 Prolonged ischemia and reperfusion is associated with the loss of cardiac endothelial NOS protein, and IPC completely prevents loss of NOS protein and increases NOS activity and cyclic guanosine monophosphate levels.37 Genetic models demonstrate a role for eNOS and nitric oxideduring early IPC. Myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury is attenuated in mice with myocyte-specific overexpression of eNOS38 and infarct size is reduced in transgenic mice overexpressing either bovine or human eNOS.39 Conversely, myocardial infarct size is markedly increased in eNOS knockout mice.40 In the present investigation, infarct size reduction by APC was blocked by L-NAME, but this NOS inhibitor did not abolish the protection of IPC. IPC may be a more robust stimulus for eliciting cardioprotective signaling than APC, and it is possible that a higher concentration of L-NAME might be necessary to block IPC compared to APC. There may also be greater redundancy of signaling pathways in IPC, only one of which includes nitric oxide as a critical intermediate. In contrast to results with L-NAME, inhibitors of Hsp90 blocked both APC and IPC. These results could suggest that Hsp90 may have binding partners in addition to or alternative of eNOS during cardioprotection, and that these are dependent on the specific mechanical (IPC) or pharmacological (APC) stimulus that induces protection. In addition, the role of APC or IPC to enhance Hsp90 association with NOS isoforms in cardiomyocytes is unknown and is the subject of ongoing investigations in our laboratory. Nonetheless, the results indicate that Hsp90 plays an important role to modulate cardioprotection during diverse preconditioning stimuli. Other heat shock proteins, such as Hsp 70, may also contribute to cardioprotection.41 Co-overexpression of Hsp 70 and Hsp 90 increases eNOS protein in endothelial cells, however unlike Hsp90, there is no evidence to indicate that Hsp 70 or other heat shock proteins regulate eNOS coupling.42

The current results should be interpreted within the constraints of several potential limitations. L-NAME produced brief hemodynamic effects during in vivo experiments that may have theoretically contributed to alterations in myocardial infarct size. However, L-NAME produced similar hemodynamic effects during IPC and APC, yet infarct size reduction was blocked only in the APC group. Thus, it is unlikely that hemodynamic changes alone substantially contributed to the results. However, myocardial oxygen consumption was not directly measured in the current investigation. Experiments were also completed in normal animals and results might be different in diseased43 or aged myocardium.44 The area at risk for infarction is an important determinant of myocardial infarct size in rabbits, but there were no differences in this variable among groups that could account for the current findings. Experiments were completed with two chemically distinct Hsp90 inhibitors. A limitation of the use of geldanamycin in the current investigation is that this drug undergoes oxidation and reduction cycling, and this cycling can produce superoxide anion. In contrast, radicicol does not demonstrate redox cycling, nor does this drug produce reactive oxygen species. Thus, the results cannot be explained by redox-sensitive effects of pharmacological inhibitors. The role of Hsp90 and eNOS during anesthetic preconditioning was investigated using isoflurane. A recent study confirmed the cardioprotective effects of sevoflurane, another halogenated anesthetic, in human endothelial cells.45 Whether Hsp90 is involved in cardioprotection produced by other volatile anesthetic agents is unknown. The effects of isoflurane to modulate Hsp90 interactions and nitric oxide production were examined in human endothelial cells and in mouse HL-1 cardiomyocytes in vitro. Results may be different in adult rabbit or human cardiomyocytes. Interactions between endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes during cardioprotection are unknown and are an important focus for future investigations.

In conclusion, the current results indicate that Hsp90 has an important function to modulate APC and IPC in vivo. APC enhances the association between Hsp90 and eNOS resulting in activation of this enzyme and enhanced production of nitric oxide in endothelial cells, but not in cardiomyocytes. The results demonstrate that protein-protein interactions are essential to the process of cardioprotection and further suggest a potential role for endothelial cell - cardiomyocyte coupling during APC and IPC.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank David Schwabe (B.S., Department of Anesthesiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) for technical assistance and Terri Misorski (B.A., Department of Anesthesiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) for manuscript preparation.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 HL03690 (JRK) and GM 066730 (DCW) from the United States Public Health Service (Bethesda, Maryland), and by research fellowship grants (JA) from the Societe Francaise d’Anesthesie et de Reanimation (SFAR, Paris, France), Novo NordiskR (Paris-La Defense, France), and the Assistance Publique des Hopitaux de Paris (APHP, Paris, France).

References

- 1.Kupatt C, Dessy C, Hinkel R, Raake P, Daneau G, Bouzin C, Boekstegers P, Feron O. Heat shock protein 90 transfection reduces ischemia-reperfusion-induced myocardial dysfunction via reciprocal endothelial NO synthase serine 1177 phosphorylation and threonine 495 dephosphorylation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1435–41. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000134300.87476.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontana J, Fulton D, Chen Y, Fairchild TA, McCabe TJ, Fujita N, Tsuruo T, Sessa WC. Domain mapping studies reveal that the M domain of hsp90 serves as a molecular scaffold to regulate Akt-dependent phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and NO release. Circ Res. 2002;90:866–73. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000016837.26733.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen JX, Lawrence ML, Cunningham G, Christman BW, Meyrick B. HSP90 and Akt modulate Ang-1-induced angiogenesis via NO in coronary artery endothelium. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:612–20. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00728.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen JX, Meyrick B. Hypoxia increases Hsp90 binding to eNOS via PI3K-Akt in porcine coronary artery endothelium. Lab Invest. 2004;84:182–90. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gratton JP, Fontana J, O’Connor DS, Garcia-Cardena G, McCabe TJ, Sessa WC. Reconstitution of an endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS), hsp90, and caveolin-1 complex in vitro. Evidence that hsp90 facilitates calmodulin stimulated displacement of eNOS from caveolin-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22268–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pritchard KA, Jr, Ackerman AW, Gross ER, Stepp DW, Shi Y, Fontana JT, Baker JE, Sessa WC. Heat shock protein 90 mediates the balance of nitric oxide and superoxide anion from endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17621–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100084200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Y, Baker JE, Zhang C, Tweddell JS, Su J, Pritchard KA., Jr Chronic hypoxia increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase generation of nitric oxide by increasing heat shock protein 90 association and serine phosphorylation. Circ Res. 2002;91:300–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000031799.12850.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCabe TJ, Fulton D, Roman LJ, Sessa WC. Enhanced electron flux and reduced calmodulin dissociation may explain “calcium-independent” eNOS activation by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6123–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toda N, Toda H, Hatano Y. Nitric oxide: involvement in the effects of anesthetic agents. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:822–42. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000287213.98020.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downey JM, Krieg T, Cohen MV. Mapping preconditioning’s signaling pathways: an engineering approach. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1123:187–96. doi: 10.1196/annals.1420.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krolikowski JG, Weihrauch D, Bienengraeber M, Kersten JR, Warltier DC, Pagel PS. Role of Erk1/2, p70s6K, and eNOS in isoflurane-induced cardioprotection during early reperfusion in vivo. Can J Anesth. 2006;53:174–82. doi: 10.1007/BF03021824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones SP, Bolli R. The ubiquitous role of nitric oxide in cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferdinandy P, Schulz R. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite in myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury and preconditioning. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:532–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen MV, Yang XM, Downey JM. Nitric oxide is a preconditioning mimetic and cardioprotectant and is the basis of many available infarct-sparing strategies. Cardiovascular Research. 2006;70:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otani H, Okada T, Fujiwara H, Uchiyama T, Sumida T, Kido M, Imamura H. Combined pharmacological preconditioning with a G-protein-coupled receptor agonist, a mitochondrial KATP channel opener and a nitric oxide donor mimics ischaemic preconditioning. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2003;30:684–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2003.03896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novalija E, Varadarajan SG, Camara AK, An J, Chen Q, Riess ML, Hogg N, Stowe DF. Anesthetic preconditioning: triggering role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in isolated hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H44–52. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01056.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiari PC, Pagel PS, Tanaka K, Krolikowski JG, Ludwig LM, Trillo RA, Jr, Puri N, Kersten JR, Warltier DC. Intravenous emulsified halogenated anesthetics produce acute and delayed preconditioning against myocardial infarction in rabbits. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1160–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200411000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ou J, Fontana JT, Ou Z, Jones DW, Ackerman AW, Oldham KT, Yu J, Sessa WC, Pritchard KA., Jr Heat shock protein 90 and tyrosine kinase regulate eNOS NO* generation but not NO bioactivity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H561–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00736.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiari PC, Bienengraeber MW, Weihrauch D, Krolikowski JG, Kersten JR, Warltier DC, Pagel PS. Role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase as a trigger and mediator of isoflurane-induced delayed preconditioning in rabbit myocardium. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:74–83. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200507000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka K, Weihrauch D, Kehl F, Ludwig LM, LaDisa JF, Jr, Kersten JR, Pagel PS, Warltier DC. Mechanism of preconditioning by isoflurane in rabbits: a direct role for reactive oxygen species. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1485–90. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200212000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Claycomb WC, Lanson NA, Jr, Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A, Izzo NJ., Jr HL-1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2979–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–5. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sessa WC, Garcia-Cardena G, Liu J, Keh A, Pollock JS, Bradley J, Thiru S, Braverman IM, Desai KM. The Golgi association of endothelial nitric oxide synthase is necessary for the efficient synthesis of nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17641–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zielonka J, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. Detection of 2-hydroxyethidium in cellular systems: a unique marker product of superoxide and hydroethidine. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:8–21. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smul TM, Lange M, Redel A, Burkhard N, Roewer N, Kehl F. Desflurane-induced preconditioning against myocardial infarction is mediated by nitric oxide. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:719–25. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200610000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venema RC, Venema VJ, Ju H, Harris MB, Snead C, Jilling T, Dimitropoulou C, Maragoudakis ME, Catravas JD. Novel complexes of guanylate cyclase with heat shock protein 90 and nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H669–78. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01025.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia B, Crowder CM. Volatile anesthetic preconditioning present in the invertebrate Caenorhabditis elegans. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:426–33. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318164d013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balligand JL. Heat shock protein 90 in endothelial nitric oxide synthase signaling: following the lead(er)? Circ Res. 2002;90:838–41. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000018173.10175.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke TF, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Cardena G, Fan R, Stern DF, Liu J, Sessa WC. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase is regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation and interacts with caveolin-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27237–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi S, Mendelsohn ME. Synergistic activation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS) by HSP90 and Akt: calcium-independent eNOS activation involves formation of an HSP90-Akt-CaM-bound eNOS complex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30821–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fulton D, Gratton JP, Sessa WC. Post-translational control of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: why isn’t calcium/calmodulin enough? J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:818–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ou J, Ou Z, Ackerman AW, Oldham KT, Pritchard KA., Jr Inhibition of heat shock protein 90 (hsp90) in proliferating endothelial cells uncouples endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:269–76. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mount PF, Kemp BE, Power DA. Regulation of endothelial and myocardial NO synthesis by multi-site eNOS phosphorylation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:271–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitsett J, Martasek P, Zhao H, Schauer DW, Hatakeyama K, Kalyanaraman B, Vasquez-Vivar J. Endothelial cell superoxide anion radical generation is not dependent on endothelial nitric oxide synthase-serine 1179 phosphorylation and endothelial nitric oxide synthase dimer/monomer distribution. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:2056–68. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ludwig LM, Tanaka K, Eells JT, Weihrauch D, Pagel PS, Kersten JR, Warltier DC. Preconditioning by isoflurane is mediated by reactive oxygen species generated from mitochondrial electron transport chain complex III. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1308–15. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000134804.09484.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muscari C, Bonafe F, Gamberini C, Giordano E, Tantini B, Fattori M, Guarnieri C, Caldarera CM. Early preconditioning prevents the loss of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and enhances its activity in the ischemic/reperfused rat heart. Life Sci. 2004;74:1127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brunner F, Maier R, Andrew P, Wolkart G, Zechner R, Mayer B. Attenuation of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice with myocyte-specific overexpression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Cardiovascular Research. 2003;57:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00649-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones SP, Greer JJ, Kakkar AK, Ware PD, Turnage RH, Hicks M, van Haperen R, de Crom R, Kawashima S, Yokoyama M, Lefer DJ. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase overexpression attenuates myocardial reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H276–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00129.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones SP, Girod WG, Palazzo AJ, Granger DN, Grisham MB, Jourd’Heuil D, Huang PL, Lefer DJ. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury is exacerbated in absence of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H1567–73. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Latchman DS. Heat shock proteins and cardiac protection. Cardiovascular Research. 2001;51:637–46. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uchiyama T, Atsuta H, Utsugi T, Oguri M, Hasegawa A, Nakamura T, Nakai A, Nakata M, Maruyama I, Tomura H, Okajima F, Tomono S, Kawazu S, Nagai R, Kurabayashi M. HSF1 and constitutively active HSF1 improve vascular endothelial function (heat shock proteins improve vascular endothelial function) Atherosclerosis. 2007;190:321–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gu W, Kehl F, Krolikowski JG, Pagel PS, Warltier DC, Kersten JR. Simvastatin restores ischemic preconditioning in the presence of hyperglycemia through a nitric oxide-mediated mechanism. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:634–42. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181672590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mio Y, Bienengraeber MW, Marinovic J, Gutterman DD, Rakic M, Bosnjak ZJ, Stadnicka A. Age-related attenuation of isoflurane preconditioning in human atrial cardiomyocytes: roles for mitochondrial respiration and sarcolemmal adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel activity. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:612–20. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318167af2d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lucchinetti E, Ambrosio S, Aguirre J, Herrmann P, Harter L, Keel M, Meier T, Zaugg M. Sevoflurane inhalation at sedative concentrations provides endothelial protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury in humans. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:262–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200702000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]