Abstract

Induction of macrophage necrosis is an important strategy used by virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) to avoid innate host defense. In contrast, attenuated Mtb causes apoptosis, which limits bacterial replication and promotes T cell cross priming by antigen presenting cells. Here we demonstrated that Mtb infection causes plasma membrane microdisruptions. Resealing of these lesions—a process crucial for preventing necrosis and promoting apoptosis—required the translocation of lysosome and Golgi apparatus-derived vesicles to the plasma membrane. Plasma membrane repair depended on prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which regulates synaptotagmin 7, the Ca++ sensor involved in the lysosome-mediated repair mechanism. By inducing production of lipoxin A4 (LXA4), which blocks PGE2 biosynthesis, virulent Mtb prevented membrane repair and induced necrosis. Thus, virulent Mtb impairs macrophage plasma membrane repair to evade host defenses.

INTRODUCTION

Metazoan cells inhabit environments frequently subjected to mechanical stress, such as occurs in skin, gut, and muscle 1 or as a consequence of interactions with pathogens 2, 3, which can result in plasma membrane lesions. To ensure survival, membrane damage is rapidly repaired. Resealing of the plasma membrane is a ubiquitous and highly conserved process based on exocytosis of endomembranes 1, 4. Although Golgi-derived vesicles are implicated in membrane repair 5, the most thoroughly studied secretory vesicles involved in plasma membrane repair resemble lysosomes 6. Exocytosis of lysosomes is induced by Ca++ and depends on the function of the Ca++-sensor synaptotagmin 7 (Syt-7) (http://www.signaling-gateway.org/molecule/query?afcsid=A002565) 7–9. Whereas Syt-7 is the calcium sensor of the lysosome 7, 10, NCS-1 (http://www.signaling-gateway.org/molecule/query?afcsid=A000957) is the major calcium sensor of the Golgi membranes 11, 12 and is involved in vesicle trafficking from the trans-Golgi network 13.

Infection with Mtb, the causative agent of tuberculosis and the predominant source of mortality from chronic pulmonary bacterial infections 9, occurs in the lung via phagocytosis of the pathogens by pulmonary macrophages (Mφ). After infection, virulent Mtb blocks phagosome maturation by interrupting acidification and lysosome fusion, which creates a protected niche within the cell for bacterial replication 14. Ultimately, intracellular infection with virulent Mtb leads to Mφ death by necrosis, a process that is characterized by plasma membrane lysis and escape of the pathogens into the surrounding tissue for a new cycle of infection. In contrast, avirulent strains of Mtb induce apoptosis, a process that leads to sequestration and killing of intracellular bacilli and also acts as a bridge from the innate to adaptive immune response 15.

The underlying mechanisms by which virulent Mtb induces necrosis or inhibits apoptosis in Mφ remain largely unknown. The host lipid mediators prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and lipoxin A4 (LXA4) exert opposing effects on the modality of Mtb induced cell death in Mφ 16. Mφ infected with attenuated Mtb produce only small amounts of LXA4 and instead elaborate prostanoids including PGE2 that protect against Mφ necrosis and promote apoptosis. In contrast, virulent Mtb infection induces LXA4 production, which inhibits PGE2 synthesis and apoptosis and leads to Mφ necrosis. These eicosanoids also play an important role in vivo since 5-lipoxygenase knockout mice (Alox5−/−) that are unable to synthesize LXA4, are more resistant to chronic infection with virulent Mtb 17. In contrast, prostaglandin E synthase knockout mice (Ptges−/−), which are unable to produce PGE2, are more susceptible to virulent Mtb 16. Moreover, the potential importance of the 5-LO pathway in humans was recently highlighted by the association of 5-LO variants with low 5-LO activity with a reduced risk of tuberculosis 18.

Mtb is endowed with a specialized protein secretion system called ESX-1, which is a type VII secretion system 19. ESX-1 secretion is thought to play a critical role in pore formation in host cell membranes 3, 20. We therefore hypothesized that virulent Mtb induces Mφ necrosis by disruption of the plasma membrane and inhibition of lesion repair. As embryonic fibroblasts from Syt-7-deficient mice are defective in lysosomal exocytosis and resealing of plasma membrane lesions 21, we further hypothesized that Syt-7 is a lysosomal component needed for Ca++-dependent exocytosis and repair of plasma membrane lesions in Mφ infected with Mtb.

Here we report that plasma membrane microdisruptions induced by attenuated Mtb were rapidly resealed by a repair mechanism that depends on recruitment of lysosomal and Golgi apparatus derived membranes and results in apoptosis of infected Mφ. In contrast, virulent Mtb inhibits membrane repair and induces necrosis of the infected Mφ. Lysosome-dependent membrane repair was promoted by PGE2 and in the absence of PGE2, infected Mφ were unable to control bacterial replication. Syt-7 is a critical gene product regulated by PGE2, since in its absence infected Mφ underwent necrosis and were unable to control Mtb growth.

RESULTS

Virulent Mtb causes persistent membrane microdisruptions

To determine whether Mtb induce plasma membrane disruptions, we assessed the permeability of infected Mφ to FDX, a 75 kDa inert impermeant fluorescent molecule that enters the cytoplasm through membrane lesions 22, 23. Commencing at 12 h after infection there was significant FDX-influx into Mφ infected with H37Rv and the FDX-influx gradually increased with time. In contrast, there was significantly less FDX-influx into Mφ infected with avirulent H37Ra (Figure 1a). To exclude the possibility that enhanced accumulation of intracellular FDX was due to increased uptake of FDX by pinocytosis, Mφ were incubated with cytochalasin B, an inhibitor of pinocytosis; this treatment did not alter the FDX influx after H37Rv infection (data not shown). These data collectively indicate that 15 – 20 h after infection with virulent H37Rv persistent membrane lesions develop in infected Mφ.

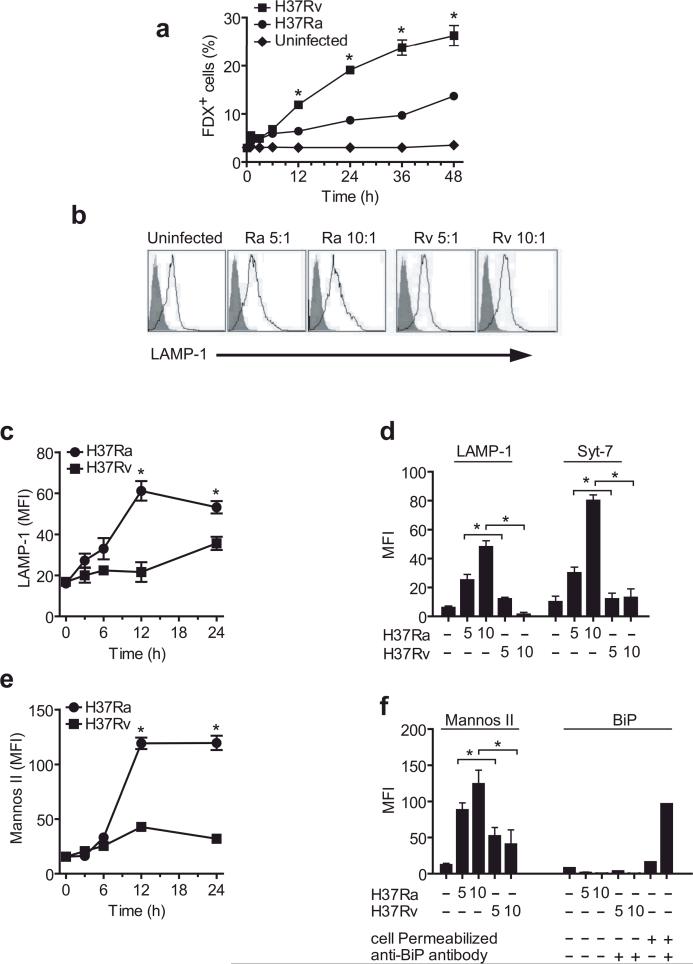

Figure 1. Infection of human Mφ with virulent H37Rv inhibits lysosomal and Golgi-mediated plasma membrane repair.

(a) Kinetics of FDX influx through membrane lesions in Mφ left uninfected or infected with H37Ra or H37Rv. (b) LAMP1 translocation to the plasma membrane lesions of human Mφ infected with H37Ra or H37Rv for 12 h. Shaded histogram is the isotype control and the open histogram is the specific LAMP1 staining. Numbers in histograms indicate the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the entire cell population. Bacterial strain and MOI is indicated above each histogram. (c,e) Kinetics of LAMP1 (c) and mannosidase II (e) translocation to the surface of human Mφ infected with H37Ra or H37Rv. (d, f) Translocation of LAMP1, Syt-7, mannosidase II and the ER marker BiP to the surface of Mφ left uninfected or infected for 12 h with H37Ra or H37R. Where indicated, Mφ were permeabilized and stained with irrelevant (−) and BiP-specific (+) antibodies. The MOI was 5:1 (5) or 10:1 (10) where indicated; otherwise an MOI of 10:1 was used. Results in all panels are representative of at least three independent experiments (error bars, s.e.m.) *, p < 0.05.

These findings could suggest that the membrane lesions inflicted by H37Ra are quickly resealed and that the lesions caused by H37Rv remain un-repaired. To determine whether lysosome recruitment is involved in membrane repair of H37Ra infected Mφ and, if so, whether transport of lysosomal membranes to the cell surface is inhibited in H37Rv infected Mφ, we measured translocation of LAMP1, a specific marker of late endosomes and lysosomes, to the cell surface 24. Mφ infected with H37Ra showed a significant translocation of LAMP1 to the cell surface which was visible as early as 3 h and was maximal by 12 h after infection (Figure 1b, c and Supplementary Figure 1, online). In contrast, little or no translocation of LAMP1 was observed in Mφ infected with virulent H37Rv.

Lysosomal trafficking and exocytosis is dependent on Syt-7, the calcium sensing protein located on late endosomes and lysosomes 2, 25. Therefore, we investigated whether cell surface Syt-7 increased after Mφ infection with avirulent H37Ra. Indeed, Syt-7 expression on the Mφ surface increased significantly after infection with H37Ra but not H37Rv (Figure 1d, Supplementary Figure 1, online). Golgi derived membranes are also implicated in plasma membrane resealing 5, so we next measured translocation of mannosidase II, a Golgi marker 26, to the cell surface. Mannosidase II expression increased on the Mφ plasma membrane starting at 12 h after H37Ra infection, but H37Rv infected Mφ maintained low cell surface expression of mannosidase II (Figure 1e, f, Supplementary Figure 1, online). On the other hand, ER derived membranes played no role in membrane repair, because the ER marker GRP78-BiP 27, 28 was not recruited to the Mφ surface after infection with either H37Ra or H37Rv (Figure 1f).

To examine whether the increased expression of lysosomal and Golgi markers on the surface of infected Mφ is due to increased protein synthesis, we measured the total quantities of mannosidase II, LAMP1, and annexin-1 protein in Mφ infected with H37Ra or H37Rv. Annexin-1 is a phospholipid-binding, anti-inflammatory protein present in many different cell types. The total amount of these proteins were not altered in Mφ infected with either H37Ra or H37Rv (Supplementary Figure 2, online), indicating that the differences in redistribution of the lysosomal and Golgi membrane compartments are not due to differences in total protein synthesis. These results collectively suggest that membranes from both the lysosomal and Golgi compartments are involved in Mφ plasma membrane resealing during avirulent mycobacterial infection.

Calcium sensors in plasma membrane repair

We next wanted to determine the role of calcium sensors in the recruitment of lysosomal and Golgi membranes to the cell surface of infected Mφ. siRNA-mediated silencing of Syt-7 expression impaired recruitment of lysosomal membranes to the Mφ surface after H37Ra infection (Figure 2a, b). However, Syt-7 silencing did not diminish, and instead actually increased, Golgi membrane translocation to the Mφ surface (Figure 2b) possibly due to a compensatory mechanism.

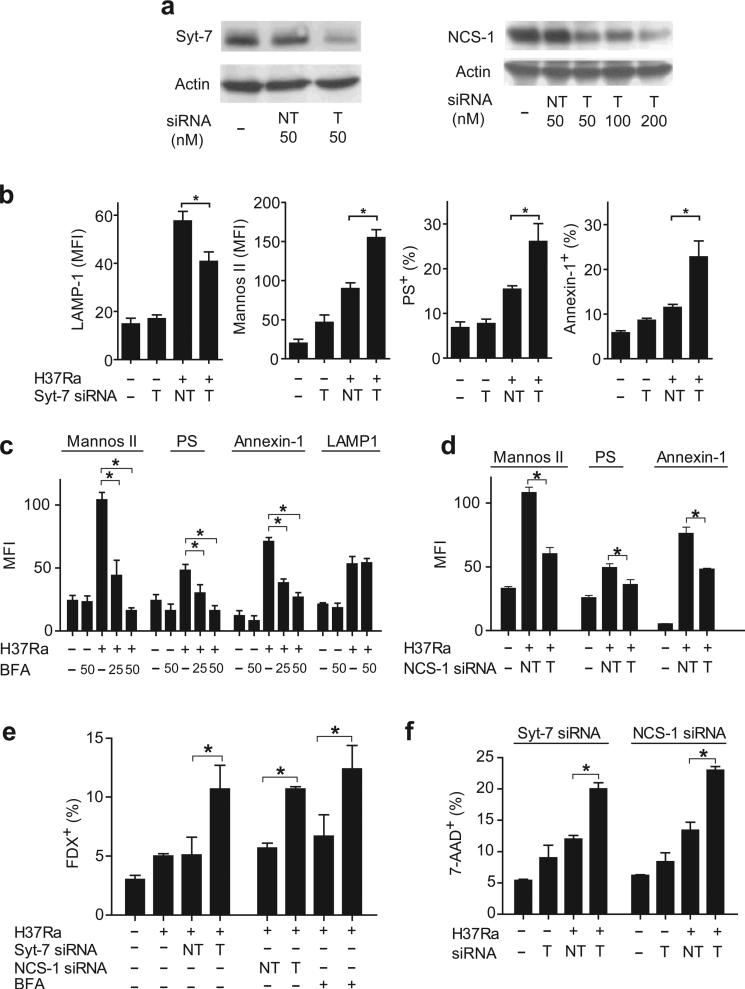

Figure 2. Distinct Ca2+ sensors regulate recruitment of lysosome and Golgi apparatus derived membranes in Mtb infected human Mφ.

(a) Expression of the Ca2+ sensors Syt-7 and NCS-1 after gene silencing in human Mφ (NT not targeted, T targeted) was measured by immunoblot. (b) Influence of Syt-7-specific siRNA on translocation of LAMP1, mannosidase II, PS, and annexin-1 to the surface of H37Ra-infected Mφ. (c) Influence of Brefeldin A (BFA) on translocation of LAMP1, mannosidase II, PS, and annexin-1 to the surface of H37Ra-infected Mφ. (d) Influence of NCS-1-specific siRNA on translocation of mannosidase II, PS, and annexin-1 to the surface of H37Ra-infected Mφ. (e) FDX influx into H37Ra infected Mφ expressing Syt-7 or NCS-1 specific siRNA or treated with Brefeldin A (50 uM). (f) Necrosis of H37Ra-infected Mφ expressing the indicated siRNA constructs. The MOI was 10:1. The results in each panel are from one representative of three independent experiments (error bars, s.e.m.) *, p < 0.05.

Phosphatidylserine (PS) and annexin-1 appear on the plasma membrane early during apoptosis to enable formation of the apoptotic envelope in Mφ infected with attenuated Mtb 29; this process is strongly impaired in Mφ infected with virulent H37Rv 30. We therefore investigated whether translocation of Golgi membranes or lysosomal vesicles to the Mφ membrane surface is required for PS exocytosis and annexin-1 recruitment to the Mφ surface. Syt-7 siRNA, which decreased LAMP1 translocation to the Mφ surface, enhanced rather than reduced PS and annexin-1 expression on the Mφ surface (Figure 2b). In contrast, BFA, a highly specific inhibitor of Golgi membrane recruitment 31, blocked mannosidase II, PS and annexin-1 translocation to the surface of Mφ infected with H37Ra in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2c). Under these conditions, translocation of LAMP1 containing lysosomal membranes to the Mφ surface was not altered.

These experiments suggest that Golgi apparatus derived vesicles are recruited to the cell surface independently from lysosomal vesicles and suggest that recruitment of the Golgi-derived membranes depends on a Ca++ sensor different from Syt-7. NCS-1 is a member of the EF family, which has a Ca++ binding motif 12, 32 and is especially abundant in Golgi apparatus derived vesicles 13. Indeed, NCS-1 siRNA (Figure 2a) had a similar effect as BFA in that it resulted in strong inhibition of Golgi membrane translocation and it significantly inhibited PS and annexin-1 translocation (Figure 2d). These findings suggest that both lysosomal and Golgi derived membranes move independently to the plasma membrane in infected Mφ.

To determine whether lysosome recruitment and Golgi membrane derived vesicle recruitment are both important for the repair of plasma membrane damage, we tested whether lysosomal and Golgi membrane translocation is required to prevent FDX influx into Mφ infected with H37Ra. Syt-7 or NCS-1 siRNA led to significantly increased FDX influx into H37Ra infected Mφ (Figure 2e). In addition, Syt-7 or NCS-1 siRNA promoted Mφ necrosis following infection with H37Ra (Figure 2f). The alternative explanation is that instead of being quickly resealed, plasma membrane lesions are not generated by avirulent H37Ra is not supported by our data (Figure 2e, f). H37Ra causes significant plasma membrane microdisruptions when repair is inhibited. These data indicate that recruitment of lysosomal and Golgi membrane derived vesicles play a critical role in the repair of plasma membrane damage following Mtb infection and is required to prevent necrosis.

PGE2 promotes plasma membrane repair

The membrane resealing process in fibroblasts is dependent on cyclic AMP (cAMP) 33, 34. We therefore investigated whether upregulation of cAMP concentrations is sufficient to trigger membrane repair. Forskolin, an activator of adenylate cyclase, increased LAMP1 and Syt-7 containing membrane translocation to the cell surface of H37Rv infected Mφ, but did not affect the translocation of Golgi membranes (Figure 3a). We previously reported that PGE2 exerts an important anti-necrotic effect in infected Mφ by preventing mitochondrial inner membrane perturbation. This protective effect of PGE2 on mitochondria is mediated by the engagement of the PGE2 receptor EP2, which induces protein kinase A (PKA) and cAMP production 30. In fact, the PGE2 receptor EP2 and EP4, but not EP1 or EP3, both activate cAMP-dependent pathways 35. Therefore, we wished to determine whether induction of membrane repair, which is triggered by an increase in cAMP, is activated by PGE2.

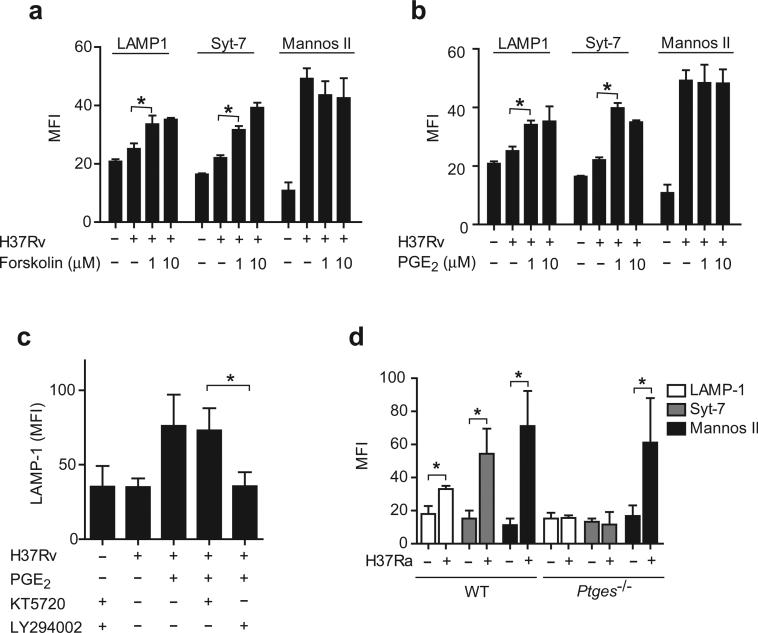

Figure 3. PGE2 reconstitutes lysosomal repair in human Mφ infected with virulent Mtb.

(a,b) Translocation of LAMP1, Syt-7 and mannosidase II to the surface of H37Rv-infected Mφ (MOI of 10:1) treated with forskolin (1–10 μM) (a) or PGE2 (b). (c) LAMP1 translocation induced by H37Rv in presence of PGE2 (1 μM) after addition of the specific PI3K inhibitor (LY294002, 10 μM) and/or the PKA inhibitor (KT5720, 50 nM). (d), Translocation of Syt-7, LAMP1 and mannosidase II to the surface of H37Ra-infected wild-type (WT) and Ptges−/− Mφ. The results in each panel are from one representative of three independent experiments (error bars, s.e.m.) *, p < 0.05.

Exogenous addition of PGE2 to H37Rv infected Mφ reconstituted plasma membrane repair as measured by enhanced LAMP1 and Syt-7 translocation to the cell surface (Figure 3b, c). In contrast, PGE2 did not affect mannosidase II containing membrane recruitment. EP2 predominantly activates PKA while EP4 receptors activate PI3K 35, 36. To determine whether PGE2-dependent activation of plasma membrane repair is caused by activation of PKA or PI3K, we examined whether the specific PKA inhibitor KT5720 37 and/or the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 38 affect PGE2-induced LAMP1 translocation to the plasma membrane of H37Rv infected Mφ. LY294002 abrogated LAMP1 translocation to the cell surface of H37Rv infected Mφ treated with PGE2, whereas KT5720 had no effect (Figure 3c). Both inhibitors alone had no effect on LAMP1 translocation. Therefore, in contrast to the protective effects of PGE2 on mitochondria, which depend on the EP2 receptor and downstream activation of PKA 16, PGE2-dependent lysosomal membrane translocation seems to require PI3K activation, which is typical of EP4 activation 39, 40.

To further assess the importance of PGE2 in stimulating lysosome-dependent plasma membrane repair, murine wild-type and PGE synthase-deficient (Ptges−/−) splenic Mφ were infected with H37Ra for 24 h. As predicted, translocation of LAMP1 and Syt-7 to the cell surface was significantly increased after infection with H37Ra in wild-type Mφ (Figure 3d). In contrast, LAMP1 and Syt-7 were not recruited to the plasma membrane of H37Ra infected Ptges−/− Mφ, which are unable to produce PGE2 (Figure 3d). Translocation of mannosidase II was detected in both wild-type and Ptges−/− Mφ. These data independently confirm that while the recruitment of lysosomal membranes is PGE2-dependent, the recruitment of Golgi derived membranes is independent of PGE2. Importantly, the propensity of Ptges−/− Mφ to undergo necrosis when infected with H37Ra is reversed when exogenous PGE2 is added 16.

These findings reveal the importance of PGE2 in inducing lysosome-dependent repair of the plasma membrane.

Balance between LXA4 and PGE2 in control of Mtb

Virulent Mtb infection of human Mφ induces LXA4 synthesis, which leads to inhibition of PGE2 production 16. We wished to understand how PGE2 and LXA4 affect the outcome of Mtb infection. Ptges−/− Mφ infected with avirulent H37Ra underwent significantly more necrosis and significantly less apoptosis than wild-type macrophages or 5-lipoxygenase-deficient (Alox5−/−) Mφ; the latter cannot produce LXA4 (Figure 4a). The converse result was observed using H37Ra-infected Alox5−/− Mφ: more apoptosis and less necrosis than wild-type and Ptges−/− Mφ. Similar observations were made using wild-type, Alox5−/− and Ptges−/− cells infected with virulent H37Rv.

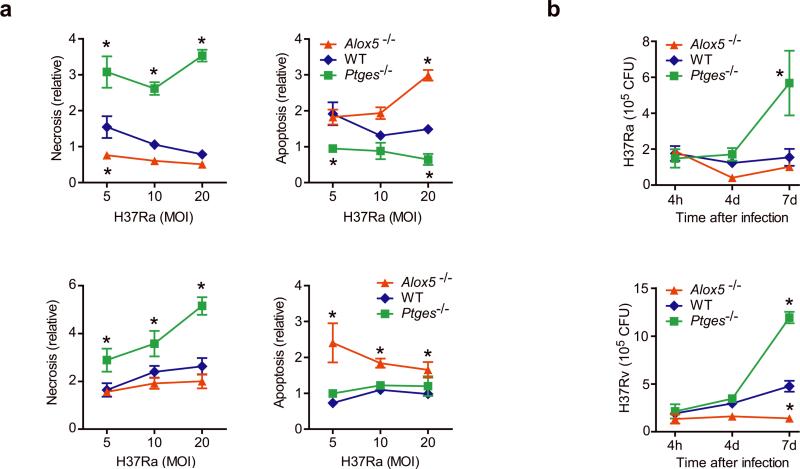

Figure 4. Bacterial growth and the death modality of Mtb infected murine Mφ is regulated by eicosanoids.

(a) Apoptosis and necrosis three days after H37Rv (bottom) or H37Ra (top) infection of Alox5−/−, wild-type (WT) and Ptges−/− Mφ. Cell death was measured by ELISA. (b) Colony forming units (CFU) of H37Rv (bottom) or H37Ra (top) at indicated times after infection (MOI 10:1) of Alox5−/− Mφ, WT and Ptges−/− Mφ. Results are representative of 3 (a) and 2 (b) independent experiments (error bars, s.e.m.) *, p < 0.05.

Ptges−/− and Alox5−/− Mφ also showed significant differences in control of Mtb growth. H37Rv grew slowly in wild-type Mφ, increasing 2.5-fold after seven days; in contrast there was little replication of H37Ra and wild-type Mφ during the experiment (Figure 4b). The growth of virulent H37Rv was significantly reduced in Alox5−/− Mφ whereas the growth of both H37Ra and H37Rv was enhanced in Ptges−/− Mφ.

Alox5−/− mice are more resistant 17 and Ptges−/− mice are more susceptible 16 to virulent mycobacterial infection. However, the question of whether the mechanisms we have delineated in vitro are reflective of in vivo pathophysiology is difficult to answer since the fate of infected Mφ can affect host resistance in many different ways 41, 42.

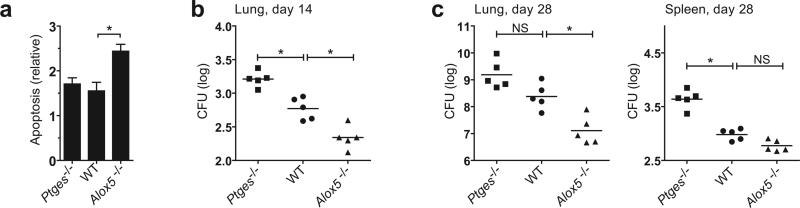

To determine whether more apoptosis occurs in the lungs of Alox5−/− mice following virulent Mtb infection, Ptges−/−, wild-type, and Alox5−/− mice were infected by the intratracheal route with 106 CFU of H37Rv, and cells were obtained by pulmonary lavage 3 d after infection. Cells from the lungs of Alox5−/− mice underwent more apoptosis than those from wild-type or Ptges−/− mice (Figure 5a).

Figure 5. The fate of Mtb-infected Mφ in vitro reflects the innate control of infection in vivo.

(a) Alox5−/−, Ptges−/−, and wild-type (WT) mice (n=3 mice per group) were intratracheally nfected with H37Rv (1×106 CFU) and BAL was collected 3 days after infection. Graph shows apoptosis of adherent antigen-presenting cells from infected Alox5−/−, WT and Ptges−/− mice as compared to uninfected controls. (b, c) Bacterial colony forming units in the spleen and/or lung 14 days (b) and 28 days (c) after intratracheal transfer of H37Rv infected Alox5−/−, Ptges−/−, or WT Mφ into Rag1−/− mice. Similar numbers of bacteria (WT log 10 = 1.81, Ptges−/− log 10 = 1.79, and Alox5−/− log 10 = 1.8) were found in the lungs of mice on day 1 after adoptive transfer. Data is from a single experiment with two time points (n=5 mice per group per time point); (error bars, s.e.m.) *, p < 0.05.

To explicitly study the consequences of Mφ function on innate immunity to Mtb, we developed an experimental model involving the adoptive transfer of Mtb infected Mφ. The advantage of this model is that it avoids the complications of analyzing knockout mice in which the deleted gene is ubiquitously expressed and affects multiple physiological processes. Thus, it allows one to specifically determine how the manipulation of the lipid mediators produced by Mtb infected Mφ alters the outcome of infection independently of their function in other cells types. Wild-type, Alox5−/− and Ptges−/− Mφ were infected in vitro with a low dose of virulent H37Rv Mtb and then transferred via the intratracheal route into Rag1−/− recipient mice as described in the “Methods”. By transferring the cells into Rag1−/− recipient mice, we could assess the functional impact of eicosanoid regulation in the absence of any contribution from the adaptive immune system.

Two weeks after adoptive transfer, the pulmonary bacterial burden was significantly higher in Rag1−/− mice that received infected Ptges−/− Mφ than in recipients of infected wild-type Mφ (Figure 5b). In contrast, the bacterial burden was significantly lower in Rag1−/− mice that received infected Alox5−/− Mφ than in those that received infected wild-type Mφ (Figure 5b). This effect was durable and was detected 28 d after transfer of the infected Mφ, in the lung as well as in the spleen (Figure 5c). The mean difference in pulmonary bacterial burden between RAG−/− mice that received 5-LO−/− Mφ and those that received wild-type Mφ was Δlog10= 1.3 (p<0.05). These experiments show that transfer of infected pro-apoptotic 5-LO−/− Mφ to RAG−/− mice strongly restricts virulent Mtb replication in vivo. Furthermore, the use of Rag1−/− recipient mice demonstrates that this effect is determined by the Mφ genotype and is independent of adaptive immunity. Thus, the balance of PGE2 and LXA4 production by infected Mφ affects the outcome of infection in the microenvironment of the lung.

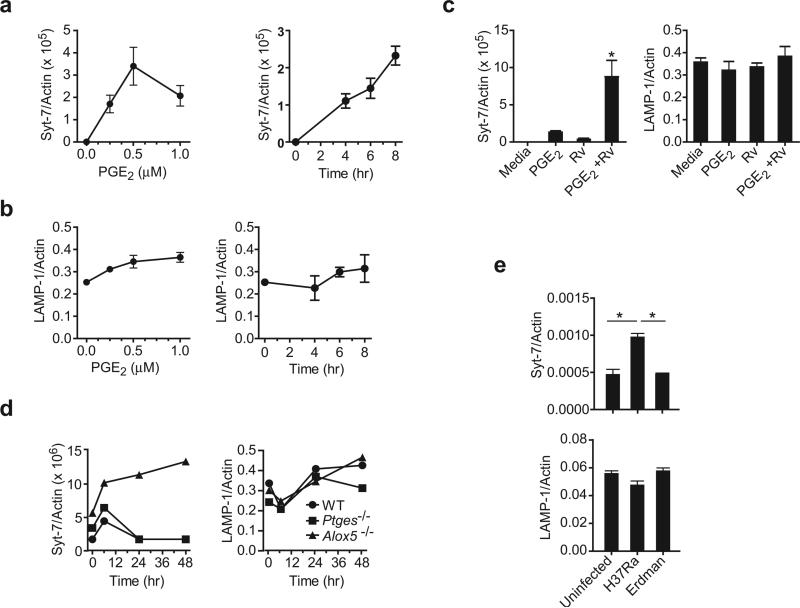

Syt-7 transcription is induced by PGE2

We have demonstrated that Syt-7 is a central regulator of Ca++ dependent lysosomal membrane translocation to the cell surface, and is required for successful membrane repair and prevention of necrosis in human Mφ. We also showed that PGE2 is indispensable for induction of lysosomal translocation to the Mφ surface and plasma membrane repair in Mtb infected Mφ. Thus we next investigated whether PGE2 is involved in Syt-7 synthesis. To this end we quantified Syt-7 mRNA transcripts in uninfected Mφ in absence and presence of PGE2. Although Syt-7 transcripts were not detected in uninfected Mφ, addition of PGE2 induced Syt-7 expression in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figure 6a). In contrast, LAMP1 transcription was not significantly affected when exogenous PGE2 was added to uninfected Mφ (Figure 6b). We next asked whether exogenous PGE2 increases Syt-7 transcript abundance in H37Rv infected Mφ. H37Rv infection and PGE2 synergistically increased Syt-7 transcript abundance (Figure 6c). LAMP1 transcript amounts were not affected under these conditions. These findings provide a mechanistic link between the ability of PGE2 to induce Syt-7, a critical regulator of lysosomal translocation, to the plasma membrane lesions and its ability to stimulate membrane repair.

Figure 6. PGE2 regulates Syt-7 expression in murine Mφ.

Dose and time response of (a) Syt-7 and (b) LAMP1 mRNA expression in naïve wild-type Mφ treated with PGE2. (c) Syt-7 and LAMP1 expression in wild-type Mφ infected or not with H37Rv after addition of PGE2 (1 μM). (d) Syt-7 and LAMP1 mRNA expression in Alox5−/−, Ptges−/− and wild-type (WT) Mφ at indicated times after infection with H37Rv. (e) Wild-type mice were infected or not by the aerosol route with a low dose (~ 100 CFU) of H37Rv or H37Ra. After 7 days of infection, RNA was extracted from the whole lung and the expression of Syt-7 and LAMP1 mRNA was measured by real-time PCR. The expression of Syt-7 or LAMP1 was normalized to β-Actin. Results are from one representative of 2 (a, b, c, and f) and 3 (d, e) independent experiments. n=3 mice per group; (error bars, s.e.m.) *, p < 0.05.

As expected, Alox5−/− Mφ infected with H37Rv expressed more Syt-7 than wild-type or Ptges−/− macrophages infected with H37Rv (Figure 6d). Syt-7 expression was only transiently induced in wild-type and Ptges−/− Mφ infected with virulent Mtb. LAMP1 expression was not affected by infection with virulent Mtb or by the capacity of the Mφ to produce eicosanoids (Figure 6d and Supplementary figure 2, online).

We corroborated these findings with in vivo experiments. Seven days following low dose aerosol infection with H37Ra, wild-type mice showed increased abundance of Syt-7 transcripts in their lungs, while mice infected with virulent Mtb had lower quantities of Syt-7 mRNA that were comparable to those in uninfected mice (Figure 6e). LAMP-1 expression was not affected by infection.

These data collectively reveal that virulent Mtb evade innate immunity by suppressing the production of PGE2 16, which is required for optimal expression of Syt-7 and lysosome-dependent plasma membrane repair.

Syt-7 is essential for control of virulent Mtb

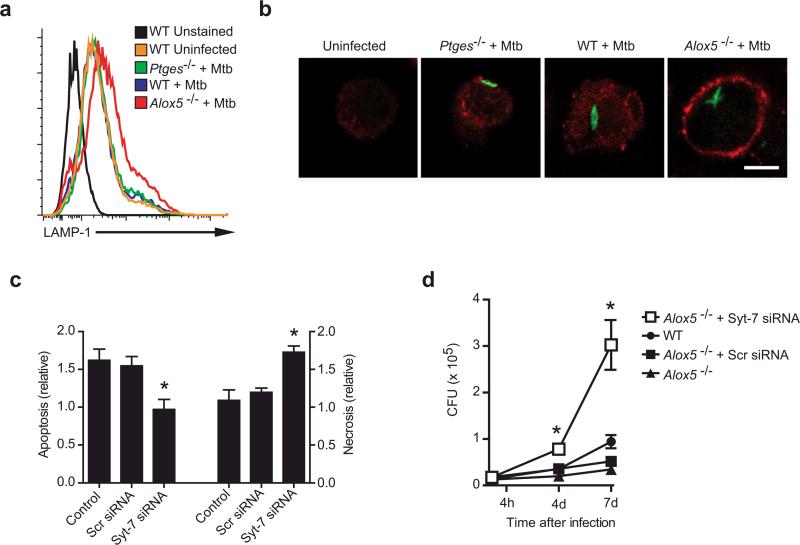

We have established the importance of eicosanoids in determining the cellular fate of Mtb infected Mφ, which determines whether the bacteria succumb to or evade innate immune control (Figure 4, 5). The finding that Syt-7 is regulated by PGE2 (Figure 6) immediately suggests a mechanism by which PGE2 induces membrane repair (Figure 3). Thus, we next wished to demonstrate a direct link between Syt-7 function, the death modality of Mtb infected Mφ, and the outcome of infection. Since our data suggest that one consequence of LXA4 induction by virulent Mtb is inhibition of Syt-7 transcription, we predict that Alox5−/− Mφ, which accumulate Syt-7 transcripts following infection (Figure 6d), will have enhanced membrane repair following H37Rv infection.

LAMP1 translocation to the cell surface was detected following H37Rv infection in Alox5−/− Mφ but not in wild-type or Ptges−/− Mφ (Figure 7a). To directly visualize whether there is enhanced plasma membrane repair in Alox5−/− Mφ, we infected wild-type, Ptges−/−, and Alox5−/− Mφ with H37Rv-GFP, and then surface labeled infected cells with an antibody specific for the luminal (extracellular) domain of LAMP1. Little LAMP1 was detected on the surface of H37Rv-GFP infected wild-type or Ptges−/− Mφ (Figure 7b). In contrast, H37Rv-GFP induced extensive LAMP1 recruitment to the surface of Alox5−/− Mφ (Figure 7b). This increased LAMP1 staining reflects a bona-fide change in LAMP1 recruitment to the cell surface as wild-type, Ptges−/−, and Alox5−/− Mφ all expressed similar amounts of intracellular LAMP1 (Supplementary Figure 3, online). These data indicate that increased amounts of PGE2 in H37Rv-infected Alox5−/− Mφ enhance lysosomal plasma membrane repair.

Figure 7. Syt-7 is essential for induction of plasma membrane repair, prevention of necrosis, and control of bacterial growth in murine Mφ.

(a,b) Translocation of LAMP1 to the cell surface of Alox5−/−, Ptges−/−, and wild-type (WT) Mφ left uninfected or 24 h after infection with H37Rv (Mtb; MOI 5:1) as analyzed by flow cytometry (a) or confocal microscopy (b). In (b) Mφ were infected with GFP-labeled H37Rv (MOI 10:1), and nonpermeabilized cells were stained with a monoclonal antibody against the lumenal domain of LAMP1. Scale bar 5 μm. (c) Alox5−/− Mφ were left untreated or were transfected with scrambled (Scr) siRNA or siRNA specific for Syt-7 for 24 h followed by H37Rv infection (MOI 5:1). Apoptosis and necrosis of the treated and infected Mφ compared to uninfected controls was measured 3 days after infection. (d) H37Rv growth was measured in Alox5−/− and WT Mφ left untreated or transfected with Syt-7-specific or scrambled (Scr) siRNA at the indicated times after infection. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments. (error bars, s.e.m.) *, p < 0.05.

To demonstrate that Syt-7 expression has a direct influence on the death modality of the infected Mφ, we performed gene silencing of Syt-7 in H37Rv-infected Alox5−/− Mφ (Figure 7c). While H37Rv induces more apoptosis than necrosis in Alox5−/− Mφ, Syt-7 gene silencing reversed this phenotype and resulted in significantly less apoptosis and more necrosis (Figure 4a, 7c). Thus, Syt-7 appears to play a pivotal role in prevention of necrosis and induction of apoptosis in Mφ infected with Mtb.

Finally, as Alox5−/− Mφ have an enhanced ability to limit Mtb replication both in vitro and in vivo (Figure 4, 5), we wished to determine whether Syt-7 function has a direct role in innate control of Mtb infection. While Alox5−/− Mφ limited bacterial replication more efficiently than wild-type Mφ, Syt-7 gene silencing significantly impaired the ability of Alox5−/− Mφ to restrict bacterial replication and lead to a significant increase in Mtb CFU (Figure 7d). Collectively, these data indicate that PGE2 is an essential mediator that stimulates Syt-7 production to activate lysosome-dependent membrane repair, which prevents necrosis, and instead leads to apoptosis and innate protection against Mtb infection.

Discussion

Necrosis is a highly regulated irreversible loss of plasma membrane integrity. Although we previously showed that virulent Mtb block formation of the apoptotic envelope in infected Mφ, and thereby lead to necrosis 29, the mechanisms facilitating necrosis in this system were not understood. Here we found that virulent Mtb perturb the repair of plasma membrane microdisruptions inflicted by the pathogen. We uncovered two distinct and essential components involved in plasma membrane repair: lysosome and Golgi derived vesicles. While Mφ infected with attenuated Mtb underwent plasma membrane repair and apoptosis, blockade of either lysosome or Golgi apparatus derived vesicle translocation to the plasma membrane resulted in significant necrosis. Silencing of the Ca++ sensor Syt-7 inhibited lysosome-dependent plasma membrane repair, but did not affect translocation of mannosidase II-containing Golgi derived membranes. In contrast, silencing of NCS-1, a Ca++ sensor present in Golgi apparatus, significantly inhibited translocation of Golgi derived membranes, and down regulated PS and annexin-1 translocation to the Mφ surface. Thus, two distinct Ca++ sensor proteins regulate lysosomal and Golgi dependent plasma membrane repair in Mtb infected Mφ. Although both lysosomal and Golgi apparatus derived vesicles are required for membrane repair, only the Golgi vesicle-dependent membrane repair facilitated exocytosis of the apoptotic marker PS and deposition of annexin-1 on the cell surface. Moreover, Golgi-derived vesicle-mediated membrane repair was PGE2 independent, which indicates that other mediators are involved in the recruitment of these membranes to the plasma membrane lesions. Further study of the Golgi-derived vesicle membrane repair pathway will considerably extend our understanding of the biology of apoptosis.

Virulent H37Rv stimulates LXA4 production in Mφ, which inhibits PGE2 production by down regulation of COX2 mRNA accumulation 16. PGE2 protects mitochondrial membranes from damage caused by Mtb infection and thereby inhibits necrosis. Here we reported that PGE2 production restores translocation of lysosomal membranes to the cell surface in Mφ infected with virulent Mtb, and that PGE2 up-regulates synthesis of Syt-7, the Ca++ sensor associated with lysosomal membrane repair 7. Thus, PGE2 activates at least two independent pathways that protect Mtb infected Mφ from necrosis. First, PGE2 acts on the PGE2 receptor EP2, which stimulates adenylate cyclase to produce cAMP by activation of protein kinase A 36 and protects against Mtb-induced mitochondrial damage 30. Second, PGE2 activates plasma membrane repair via PI3K, which most likely involves the EP4 receptor 35, 40. Thus, PGE2 protects Mtb infected cells against necrosis by preventing mitochondrial inner membrane instability and plasma membrane disruption.

Even attenuated H37Ra resulted in a highly virulent phenotype in Ptges−/− Mφ. On the other hand, virulent H37Rv induced an attenuated phenotype in Alox5−/− Mφ, in which PGE2 production is not counter-regulated by LXA4. Thus, in an intracellular milieu dominated by PGE2, infected Mφ undergoes more apoptosis and restricts Mtb growth. These findings indicate that the capacity of host Mφ to produce PGE2 modulates the virulence of Mtb. Therefore, the innate host response is capable of modifying the phenotypic expression of bacterial virulence.

Alox5−/− mice were more resistant and Ptges−/− mice were more susceptible than wild-type mice when infected by the aerosol route with Mtb 16, 17. However, our transfer experiments showed that the fate of the infected Mφ is a key determinant of the relative resistance of these mice. While Alox5−/−, Ptges−/−, and wild-type Mφ were all infected to a similar degree, transfer of infected Alox5−/− Mφ resulted in a much less severe systemic infection than transfer of infected wild-type or Ptges−/− Mφ. Therefore, the fate of transferred Mφ, whether apoptotic or necrotic, has a durable impact on the course of infection. This is the first direct demonstration that the death modality of infected Mφ alters the course of Mtb infection in vivo. Thus, we provide a direct mechanistic link between the beneficial function of PGE2 and outcome of infection.

Although we have gained some knowledge about the donor vesicles involved in plasma membrane repair of the Mtb infected Mφ and about the importance of Ca++ sensors in the regulation of plasma membrane repair, exactly how PGE2 facilitates membrane repair remains unclear. Attenuated Mtb triggered PGE2 dependent LAMP1 translocation to the Mφ surface in a PI3K dependent manner. Interestingly, phagosome-lysosome fusion is thought to be inhibited in Mtb infected Mφ 43 by constant removal of PI3P from the endosomal membranes by SapM, a pathogen-derived phosphatase in a manner independent of cytosolic Ca++ 44. It is therefore likely that PGE2 up-regulates PI3K activity to generate sufficient PI3P for membrane repair. If pathogen-mediated depletion of PI3P indeed affects both phagosome-lysosome fusion and plasma membrane repair, it could be assumed that plasma membrane repair and phagosome-lysosome fusion are mediated by related mediators. This observation is consistent with previous work demonstrating that ESX1 encoded proteins are required for translocation of Mtb from the phagolysosome to the cytosol 45, and our findings that LAMP1 translocation to Mφ plasma membrane lesions also depended on ESX1 encoded proteins (data not shown). In addition, other studies reported that the early intracellular survival of Salmonella and Yersinia is inhibited in murine embryonic fibroblasts as a consequence of Syt-7 dependent phago-lysosome fusion 2.

Here we established a causal relationship between the capacity of Mφ to restrict mycobacterial growth, and their ability to reseal membrane lesions inflicted by the pathogen and induce apoptosis. If membrane repair is abrogated, infected Mφ are doomed to become necrotic and support enhanced bacterial growth. Thus, inhibition of membrane repair by blocking PGE2 production represents a critical mechanism that allows virulent bacilli to replicate, induce necrosis, and finally to escape from the host Mφ and infect other cells. Better understanding of the mechanisms by which Mtb induces necrosis might identify novel targets for drugs that modulate innate immune responses to control the initial infection as well as to enhance adaptive immunity.

METHODS

Materials

Mouse LAMP1 ab (1D4B, BD Biosciences); Human LAMP1 ab (H4A3, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa), mannosidase II ab (MMS-110R, Covance and ab12277, abcam), and GRP78/BiP ab (ab21685, abcam); anti Syt-7 Ab (105 172, Synaptic Systems GmBH); goat anti mouse IgG1 (SKU# A10538, Molecular Probes); murine IgG (641410, BD Biosciences); rabbit annexin-1 ab (71–3400, Zymed Laboratories); anti-PSmurine monoclonal Ab (1H6, Upstate Biotechnology), rabbit IgG (Upstate Biotechnology); Cy3 donkey anti-rat (Jackson Immuno); anti-CD11b (550282, BD Biosciences), anti-F4/80 (552958, BD Biosciences); anti-β-actin mab (37200, Pierce Biotechnology); PGE2 (14010, Cayman Chemical); Forskolin, Brefeldin A, LY294002, and KT5720 (Sigma); CD11b MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotech Inc., Auburn, CA); Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM), RPMI-1640, Opti-MEM I, Reduced Serum Medium, Oligofectamine, HEPES and DTT (Invitrogen).

Mice

Six to ten week old C57BL/6 or Rag1−/− mice were from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME); Alox5−/− and Ptges−/− mice (N5 back cross onto the C57BL/6 background) obtained from Dr. Beverly Koller, University of NC, were bred locally. All procedures were approved by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cells and culture

Human studies were approved by the Partners Human Research Committee. Human mononuclear cells from purchased leukopacs of healthy donors are plated for FACS analysis at 4×105 cells / ml / well in 12-well cluster plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY), for transfection with siRNA at 5×105 cells / ml / well in 12-well cluster plates (Corning). Mφ were cultured for 7 days in IMDM (Invitrogen) with 10% human AB serum (Gemini, Woodland, CA).

Murine CD11b+ cells were purified from thioglycollate (3 %) elicited peritoneal Mφ harvested from WT, Alox5−/− and Ptges−/− mice by MACS column purification. For some experiments murine spleen Mφ were cultured for 8 – 10 days in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Gemini), 1% HEPES, 1% penicillin / streptomycin and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol. The purified cells were > 95% CD11b+ and F4/80+, as determined by flow cytometry. Mφ (1 × 105 / well) were allowed to adhere in a 96 well culture plate for 24 h.

Bacteria

The virulent Mtb strain Erdman, H37Rv, GFP-labeled H37Rv and the attenuated strain H37Ra (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) prepared as described before30 were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) with BBL Middlebrook OADC Enrichment (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) and 0.05% Tween 80 (Difco, Detroit, MI) and re-suspended in 7H9 broth at 5×107 CFU/ml. Aggregation was prevented by sonication for 10 s. The bacteria were allowed to settle for 10 min.

In vitro infections

Macrophages were infected with virulent H37Rv or avirulent H37Ra at varying MOI as previously described 16, 46. At different time points cells were lysed in H20 for 5 min and mycobacterial CFU were enumerated by plating serially diluted cell lysates on Middlebrook 7H10 agar plates (REMEL), and cultured at 37°C. Colonies were counted after 21 days.

Aerosol infection of mice

C57BL/6 and Ptges−/− mice were infected with virulent M. tuberculosis (Erdman strain) or H37Ra via the aerosol route using a nose-only exposure unit (Intox Products) and received approximately 100 CFU/mouse 47. After one week, mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and the lung was aseptically removed and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction.

Adoptive transfer model of infection

CD11b+ cells were purified from thioglycollate (3 %) elicited peritoneal Mφ harvested from WT, Ptges−/− and Alox5−/− mice by MACS column purification. Suspended Mφ from each group of mice were infected in vitro using a low MOI (~0.02) of virulent H37Rv for 30 minutes. Free bacteria were then removed by 6 washes with PBS, each time followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 1000 RPM at 4°C. Cells were resuspended in PBS at 0.5 × 106/40 μl, and then transferred by the intratracheal (i.t.) route 48into naïve Rag1 deficient mice. Two and four weeks after adoptive transfer, the mice were euthanized and their lungs and spleens were removed and individually homogenized in 0.9% NaCl-0.02% Tween 80 with a Mini-Bead-Beater-8 (BioSpec Products). Viable bacteria were enumerated by plating 10-fold serial dilutions of organ homogenates onto 7H11 agar plates (Remel). Colonies were counted after 3 weeks of incubation at 37°C.

FACS analysis

Cells were stained with anti LAMP1, GRP78/BiP, Syt-7 or mannosidase II abs in IMDM for 20 min (20 μg / ml) at 37°C. After washing the Mφ were incubated at 37°C with secondary fluorescent rabbit anti mouse antibodies (100 μg / ml) for 20 min and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. Cells were dislodged with a rubber policeman, washed with PBS and resuspended in PBS with 1 % BSA. Flow cytometry was performed by using a BD FACSort flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

In vitro assays of necrosis and apoptosis

Necrosis of Mφ in vitro was assessed with FDX influx or 7-amino-actinomycin D (7AAD) staining by FACS analysis. Adherent infected and non-infected human Mφ (5 × 105 / well) were incubated at 4°C, washed and the medium replaced by the same amount of ice cold IMDM containing 2 mg / ml FDX (Mr 75,000) for 15 min. After 4 x washing with ice cold IMDM the cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde over night, scraped off using a rubber policeman, washed, and subjected to FACS analysis. Cells containing more than 30 μM FDX as determined by calibration were gated. Adherent Ptges−/− and wild type spleen Mφ were incubated for 15 min at 37°C with medium containing 2.5 μg / ml 7-AAD and fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde over night. Thereafter Mφ were washed 2x with PBS and scraped off the plates, resuspended in 0.3 ml PBS and analysed using a flow cytometer. In some experiments apoptosis and necrosis were measured with cell death detection ELISAPLUS photometric enzyme immunoassay (11 920685 001; Roche Applied Science) for the quantification of cytoplasmic (apoptosis) and extracellular (necrosis) histone-associated DNA fragments according to the specifications of the manufacturer. The relative amount of necrosis or apoptosis was calculated as a ratio of the O.D. of infected macrophages to uninfected control macrophages.

Immunoblot analysis

After incubation with Mtb (MOI 10:1), cells were harvested and lysed with 1×SDS sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% w/vol SDS, 10% glycerol, 50mM DTT, 0.01% w/vol bromophenol blue). The cell lysates were sonicated for 10 s, centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min and resolved by SDS-PAGE on 15% acrylamide gels by using β-actin as a loading control. Murine antibodies were used to detect Syt-7 and NCS-1.

Real time PCR

Total RNA from lung tissues or Mφ cultures was isolated by using the PureLink Total RNA Purification System (Invitrogen) and transcribed into cDNA using the Quantitect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. cDNAs were denatured for 10 min at 95°C. Specific DNA fragments were amplified using a Max3000p Stratagene cycler with steps of 15 s at 95°C, 60 s at 56°C, and 30 s at 72°C for 40 PCR cycles. The oligonucleotide primers used for mouse β-Actin are 5'-AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC-3' (forward) and 5'-CAATAGTGATGACCTGGC CGT-3' (reverse) and for Syt-7 are 5'-CCGTCAGCCTTAGCGTCAC-3' (forward) and 5'-GCAGGCAACTTGATGGCTTTC-3' (reverse). The amount of amplified Syt-7 DNA fragments was normalized to β-Actin.

Immunostaining and confocal microscopy

Mouse Mφ were mounted on poly-d lysine coverglass in phenol-red-free media and infected with GFP-labeled virulent or avirulent TB for 24h. Mφ were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 minutes and blocked with 10% horse serum in PBS overnight at 4° C. Coverslips were incubated with anti-LAMP1 (1:10,000) LAMP-1 at 25° C for 1 hour. Cells were then washed thrice with PBS and stained with Cy3 donkey anti-rat (1:2000) at room temperature for 1 hour. Cells then were washed and mounted for imaging. Microscope images were acquired at the Brigham and Women's Confocal Core Facility using a Nikon TE2000-U inverted microscope, a Nikon C1 Plus confocal system, a 60x Nikon Plan Apochromat objective, a 10 mW Spectra Physics 488 nm argon laser, a Melles Griot Red HeNe 543 nm laser, and Chroma 515/30 and 543 emission filters, and a 30 μm pinhole. Images were acquired under identical exposure conditions and micrographs were compiled and analyzed using Nikon EZ-C1 v3.8 and Adobe Photoshop v10.0.1.

Silencing of the gene encoding human Syt-7 and NCS-1

The human Syt-7 siRNA target sequence was 5'-AAGAATGCTAATGTAAAGCAA-3' and the non-targeted (nt) siRNAs 5'-GAAUUAAGUACAAGUUAGAU-3' were generated by Qiagen. The human NCS-1 siRNA (sc-36019) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA. Cells were cultured in IMDM with 10% human AB serum and medium was changed 1 day prior to transfection. All siRNAs were used at a final concentration of 50 nM by diluting with Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium. To oligofectamine (Invitrogen, 1:200 dil.) fresh IMDM containing 30% human AB serum (Gemini, Woodland, CA) was added to bring the serum concentration to 10%. After transfection (48 h at 37°C), the cells were infected with Mtb.

Silencing of the gene encoding mouse Syt-7

Primers from the gene encoding mouse Syt-7 (Mouse GeneBank accession number NM-018801) were used to design siRNA. The sequence of targeted Syt-7 was CTCCATCATCGTGAACATCAT (Qiagen 439893). The non-targeted AllStars (Qiagen 1027280) was used as a negative control. All siRNAs were used at a final concentration of 50 nM. Cells were transfected using Hiperfect Transfection Reagent according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Qiagen). To examine the effect of siRNA transfection, cells were harvested and analyzed using Western blotting or real time PCR.

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. The data were analyzed by using Microsoft Excel Statistical Software (Jandel, San Rafael, CA) using the t test for normally distributed data with equal variances. In some experiments, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett's posttest and with Bonferroni's posttest were performed using Prism version 5 for Windows (Graph-Pad Software).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. I-Cheng for critical reading of the manuscript. This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health grants (AI50216 and AI072143) and the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec Postdoctoral Fellowship (to M. Divangahi).

Reference List

- 1.McNeil PL, Steinhardt RA. Plasma membrane disruption: repair, prevention, adaptation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003;19:697–731. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.140101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roy D, et al. A process for controlling intracellular bacterial infections induced by membrane injury. Science. 2004;304:1515–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.1098371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith J, et al. Evidence for pore formation in host cell membranes by ESX-1-secreted ESAT-6 and its role in Mycobacterium marinum escape from the vacuole. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:5478–5487. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00614-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bi GQ, Alderton JM, Steinhardt RA. Calcium-regulated exocytosis is required for cell membrane resealing. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1747–1758. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Togo T, Alderton JM, Bi GQ, Steinhardt RA. The mechanism of facilitated cell membrane resealing. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 5):719–731. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.5.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez A, Webster P, Ortego J, Andrews NW. Lysosomes behave as Ca2+-regulated exocytic vesicles in fibroblasts and epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137:93–104. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez I, et al. Synaptotagmin VII regulates Ca(2+)-dependent exocytosis of lysosomes in fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 2000;148:1141–1149. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martens S, McMahon HT. Mechanisms of membrane fusion: disparate players and common principles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:543–556. doi: 10.1038/nrm2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sudhof TC. Synaptotagmins: why so many? J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:7629–7632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craxton M, Goedert M. Alternative splicing of synaptotagmins involving transmembrane exon skipping. FEBS Lett. 1999;460:417–422. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01382-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgoyne RD, O'Callaghan DW, Hasdemir B, Haynes LP, Tepikin AV. Neuronal Ca2+-sensor proteins: multitalented regulators of neuronal function. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourne Y, Dannenberg J, Pollmann V, Marchot P, Pongs O. Immunocytochemical localization and crystal structure of human frequenin (neuronal calcium sensor 1) J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:11949–11955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haynes LP, Thomas GM, Burgoyne RD. Interaction of neuronal calcium sensor-1 and ADP-ribosylation factor 1 allows bidirectional control of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase beta and trans-Golgi network-plasma membrane traffic. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:6047–6054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armstrong JA, Hart PD. Response of cultured macrophages to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with observations on fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. J. Exp. Med. 1971;134:713–740. doi: 10.1084/jem.134.3.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaible UE, et al. Apoptosis facilitates antigen presentation to T lymphocytes through MHC-I and CD1 in tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1039–1046. doi: 10.1038/nm906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen M, et al. Lipid mediators in innate immunity against tuberculosis: opposing roles of PGE2 and LXA4 in the induction of macrophage death. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:2791–2801. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bafica A, et al. Host control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is regulated by 5-lipoxygenase-dependent lipoxin production. J Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1601–1606. doi: 10.1172/JCI23949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herb F, et al. ALOX5 variants associated with susceptibility to human pulmonary tuberculosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:1052–1060. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdallah AM, et al. Type VII secretion--mycobacteria show the way. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:883–891. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu T, et al. The primary mechanism of attenuation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin is a loss of secreted lytic function required for invasion of lung interstitial tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:12420–12425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635213100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakrabarti S, et al. Impaired membrane resealing and autoimmune myositis in synaptotagmin VII-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:543–549. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terasaki M, Miyake K, McNeil PL. Large plasma membrane disruptions are rapidly resealed by Ca2+-dependent vesicle-vesicle fusion events. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:63–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNeil PL. Incorporation of macromolecules into living cells. Methods Cell Biol. 1989;29:153–173. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granger BL, et al. Characterization and cloning of lgp110, a lysosomal membrane glycoprotein from mouse and rat cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:12036–12043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reddy A, Caler EV, Andrews NW. Plasma membrane repair is mediated by Ca(2+)-regulated exocytosis of lysosomes. Cell. 2001;106:157–169. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novikoff PM, Tulsiani DR, Touster O, Yam A, Novikoff AB. Immunocytochemical localization of alpha-D-mannosidase II in the Golgi apparatus of rat liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1983;80:4364–4368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hart DN, Starling GC, Calder VL, Fernando NS. B7/BB-1 is a leucocyte differentiation antigen on human dendritic cells induced by activation. Immunology. 1993;79:616–620. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin HY, et al. The 170-kDa glucose-regulated stress protein is an endoplasmic reticulum protein that binds immunoglobulin. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1993;4:1109–1119. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.11.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gan H, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis blocks crosslinking of annexin-1 and apoptotic envelope formation on infected macrophages to maintain virulence. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:1189–1197. doi: 10.1038/ni.1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen M, Gan H, Remold HG. A Mechanism of Virulence: Virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis Strain H37Rv, but Not Attenuated H37Ra, Causes Significant Mitochondrial Inner Membrane Disruption in Macrophages Leading to Necrosis. J Immunol. 2006;176:3707–3716. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klausner RD, Donaldson JG, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Brefeldin A: insights into the control of membrane traffic and organelle structure. J. Cell Biol. 1992;116:1071–1080. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.5.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Callaghan DW, et al. Differential use of myristoyl groups on neuronal calcium sensor proteins as a determinant of spatio-temporal aspects of Ca2+ signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:14227–14237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Togo T, Alderton JM, Steinhardt RA. Long-term potentiation of exocytosis and cell membrane repair in fibroblasts. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:93–106. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez A, Martinez I, Chung A, Berlot CH, Andrews NW. cAMP regulates Ca2+-dependent exocytosis of lysosomes and lysosome-mediated cell invasion by trypanosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:16754–16759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Regan JW. EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptor signaling. Life Sci. 2003;74:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujino H, West KA, Regan JW. Phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 and stimulation of T-cell factor signaling following activation of EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptors by prostaglandin E2. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:2614–2619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simpson CS, Morris BJ. Induction of c-fos and zif/268 gene expression in rat striatal neurons, following stimulation of D1-like dopamine receptors, involves protein kinase A and protein kinase C. Neuroscience. 1995;68:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00122-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujino H, Salvi S, Regan JW. Differential regulation of phosphorylation of the cAMP response element-binding protein after activation of EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptors by prostaglandin E2. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;68:251–259. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.011833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujino H, Xu W, Regan JW. Prostaglandin E2 induced functional expression of early growth response factor-1 by EP4, but not EP2, prostanoid receptors via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:12151–12156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212665200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hinchey J, et al. Enhanced priming of adaptive immunity by a proapoptotic mutant of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2279–2288. doi: 10.1172/JCI31947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winau F, et al. Apoptotic vesicles crossprime CD8 T cells and protect against tuberculosis. Immunity. 2006;24:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deretic V, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhibition of phagolysosome biogenesis and autophagy as a host defence mechanism. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:719–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vergne I, et al. Mechanism of phagolysosome biogenesis block by viable Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:4033–4038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409716102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Wel NN, et al. M. tuberculosis and M. leprae translocate from the phagolysosome to the cytosol in myeloid cells. Cell. 2007;129:1287–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sada-Ovalle I, Chiba A, Gonzales A, Brenner MB, Behar SM. Innate invariant NKT cells recognize Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages, produce interferon-gamma, and kill intracellular bacteria. PLoS. Pathog. 2008;4:e1000239. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woodworth JS, Wu Y, Behar SM. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD8+ T cells require perforin to kill target cells and provide protection in vivo. J. Immunol. 2008;181:8595–8603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Divangahi M, et al. NOD2-deficient mice have impaired resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection through defective innate and adaptive immunity. J. Immunol. 2008;181:7157–7165. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.