Summary

Specification of the dorsoventral axis in Xenopus depends on rearrangements of the egg vegetal cortex following fertilization, concomitant with activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. How these processes are tied together is not clear, but RNAs localized to the vegetal cortex during oogenesis are known to be essential. Despite their importance, few vegetally localized RNAs have been examined in detail. In this study, we describe the identification of a novel localized mRNA, trim36, and characterize its function through maternal loss-of-function experiments. We find that trim36 is expressed in the germ plasm and encodes a ubiquitin ligase of the Tripartite motif-containing (Trim) family. Depletion of maternal trim36 using antisense oligonucleotides results in ventralized embryos and reduced organizer gene expression. We show that injection of wnt11 mRNA rescues this effect, suggesting that Trim36 functions upstream of Wnt/β-catenin activation. We further find that vegetal microtubule polymerization and cortical rotation are disrupted in trim36-depleted embryos, in a manner dependent on Trim36 ubiquitin ligase activity. Additionally, these embryos can be rescued by tipping the eggs 90° relative to the animal-vegetal axis. Taken together, our results suggest a role for Trim36 in controlling the stability of proteins regulating microtubule polymerization during cortical rotation, and subsequently axis formation.

Keywords: Xenopus, Dorsal axis, Wnt, Microtubules, Cortical rotation, Trim, Ubiquitylation

INTRODUCTION

Understanding the establishment of the embryonic body axis from a symmetrical egg has been a long-standing problem in developmental biology. In amphibian eggs, axial determination requires a dorsally directed rotational movement of the egg cortex (cortical rotation) during the first cell cycle (Elinson and Rowning, 1988; Vincent et al., 1986). Cortical rotation is driven by a parallel array of microtubules beneath the cortex (Elinson and Rowning, 1988), and the degree of rotation is correlated with the size and extent of Spemann organizer formation, the main determinant of dorsal fate in the embryo (Gerhart et al., 1989). Cortical rotation is thought to transport axial determinants to the dorsal side (Kageura, 1997; Marikawa et al., 1997) along the microtubule array, resulting in activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and in the dorsal stabilization of β-catenin (reviewed by Weaver and Kimelman, 2004).

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is clearly sufficient for axis formation (McMahon and Moon, 1989; Sokol et al., 1995; Yost et al., 1996). The requirement for Wnt activity in vertebrates was first demonstrated through the depletion of maternal β-catenin mRNA using antisense oligonucleotides (Heasman et al., 1994). β-catenin-depleted embryos are ventralized, lacking dorsal tissues of all three germ layers, including the neural tube, notochord and somites. Additional maternal depletion studies showed that other Wnt/β-catenin components are also required for proper axis formation (Belenkaya et al., 2002; Houston et al., 2002; Kofron et al., 2001; Sumanas et al., 2000; Yost et al., 1998). Despite the importance of both cortical rotation and Wnt/β-catenin signaling in axis determination, how these two processes are initiated and their inter-relationships are not clearly understood.

Recent studies have shown that the Wnt ligand Wnt11 plays a crucial role in axis formation and maternal Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Tao et al., 2005). wnt11 mRNA is vegetally localized during oogenesis to the region of the germ plasm (Kloc and Etkin, 1995; Ku and Melton, 1993), which is a subcellular aggregation of mitochondria, membranous organelles and ribonuceloproteins that is required for establishing the germline (reviewed by Houston and King, 2000b). Germ plasm is anchored in the cortex and is displaced dorsally by cortical rotation, thus distributing wnt11 mRNA to the dorsal side (Tao et al., 2005). Depletion of maternal wnt11 mRNA using antisense oligonucleotides results in ventralized embryos, and molecular epistasis experiments demonstrate that Wnt11 lies upstream of β-catenin (Tao et al., 2005).

An alternative model suggests that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is achieved by intracellular transport of β-catenin stabilizing agents dorsally along vegetal microtubules (Weaver and Kimelman, 2004). Evidence supporting this model comes from cytoplasmic transplantation experiments (Kageura, 1997), the visualization of Dishevelled (Miller et al., 1999) and Gbp (also known as Frat1) (Weaver et al., 2003) movement during cortical rotation and the ventralization phenotype observed upon depletion of maternal gbp (Yost et al., 1998). However, these models are not mutually exclusive, as the enrichment of Wnt activators on the dorsal side might sensitize these cells to ongoing Wnt signaling. Either model would require the vegetal microtubule array; however, the mechanisms that form this array and the extent of its involvement in Wnt signaling are not well understood.

The formation of vegetal microtubule arrays during the first cell cycle is conserved in many organisms (Eyal-Giladi, 1997), whereas cortical rotation per se and wnt11 localization and function in axis formation might be features specific to basal fish and amphibians. Recent studies have shown that the germ-plasm-localized mRNA fatvg (adipophilin), which encodes a lipid-vesicle-associated protein, is required for axis formation by regulating the movement of vesicles during cortical rotation (Chan et al., 2007). These data, together with the role of localized wnt11, suggest that germ-plasm-localized molecules might play significant roles in axis formation as well as in germ-cell formation. To better understand the functions of localized mRNAs, we undertook the identification and functional analysis of novel vegetally localized mRNAs in Xenopus. In this work, we describe one such novel localized mRNA, the Xenopus homolog of tripartite motif-containing 36 (trim36).

Trim36 is a member of the large Tripartite motif-containing protein family [known as the Trim or RBCC family (reviewed by Meroni and Diez-Roux, 2005)]. Trim proteins are defined by a conserved domain architecture, consisting of an N-terminal RING finger domain, in combination with adjacent B-box-type zinc fingers and a coiled-coil motif. Mammalian Trim36 localizes to microtubules in cultured cells and is thought to have a role in acrosome exocytosis (Kitamura et al., 2003; Kitamura et al., 2005). Here we show that, in Xenopus, trim36 mRNA is localized vegetally in the oocyte and is enriched in the germ plasm and adult germ cells. Interestingly, we find that depletion of maternal trim36 results in ventralized embryos. We show that Trim36 does not regulate Wnt signal transduction directly, that Trim36 is required for polymerization of cortical microtubules during cortical rotation and that ubiquitin ligase activity is likely to be required for this function. These data provide evidence that Trim36 is essential for positioning the dorsalizing Wnt signal in early development and further suggest that proteins encoded by vegetally localized mRNAs are important in the control of microtubule polymerization or stabilization in the vegetal cortex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oocytes and embryos

Oocytes were manually defolliculated and cultured in a modified oocyte culture medium [OCM; 70% L-15 media, 0.04% BSA, 1 mM GlutaMAX media, 1.0 μg/ml gentimicin, pH 7.6-7.8 (Heasman et al., 1991)] at 18°C. Embryos were obtained as described (Sive et al., 2000; Kerr et al., 2008). For tipping experiments, eggs were de-jellied and sorted within 20 minutes of fertilization; the colored eggs were then transferred to a Nitex mesh dish containing 5% Ficoll in 0.3× MMR. Individual eggs were oriented with the sperm entry point uppermost and were left in place until the first cleavage. The buffer was gradually changed to 0.1× MMR and embryos were cultured to the tailbud stage.

Plasmids

A full-length cDNA for trim36 in the vector pCMV-SPORT6 was obtained commercially (Open Biosystems) and the insert size was confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion. The coding region (CDS) for trim36 was amplified by PCR and cloned into pCR8/GW/TOPO (Invitrogen). Clones were verified by sequencing and selected clones in the 5′-L1 to L2-3′ orientation were inserted via recombination into a pCS2+ Gateway-converted vector (custom vector conversion kit; Invitrogen). Details of the Gateway plasmid are available upon request. Template DNA for sense transcription from trim36-pCS2+ was prepared by NotI digestion and was cleaned by proteinase K digestion. Capped messenger RNA was synthesized using SP6 mMESSAGE mMACHINE Kits (Ambion).

Antisense oligos and host transfer

Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (oligos) used were HPLC-purified phosphorothioate-phosphodiester chimeric oligos (Integrated DNA Technologies) with the following sequences (* indicates phosphorothioate linkages): trim36-3, 5′-C*T*TCCAGGTGTCGATG*C*T-3′ (nt 408-426); trim36-4, 5′-G*C*CTATACTTCTTCGC*C*C-3′ (nt 506-523); trim36-MO-A, 5′-CCCGTCTCCTCCATCTGCGCTTGTT-3′ (nt 198-222); β-catenin 303,5′-T*G*C*CTTTCGGTCTGG*C*T*C-3′ (Heasman et al., 1994).

Oocytes were injected in the vegetal pole (doses of oligos are indicated in the text) and cultured for 24 hours at 18°C before being matured by treatment with 2.0 μM progesterone. For rescue experiments, mRNAs were injected immediately prior to progesterone treatment. Matured oocytes were colored with vital dyes, transferred to egg-laying host females, recovered and fertilized essentially as described (Heasman et al., 1991).

Analysis of gene expression using real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from oocytes and embryos using proteinase K and then treated with RNase-free DNase as described (Houston and Wylie, 2005). Real-time RT-PCR was carried out using the LightCycler 480 System (Roche Applied Science). Samples were normalized to ornithine decarboxylase (odc) levels and relative expression values were calculated against a standard curve of control cDNA. Samples lacking reverse transcriptase in the cDNA synthesis reaction failed to give specific products. The data shown are representative individual experiments using unreplicated samples; experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results. Primer sequences and detailed protocols are available upon request.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed essentially as described (Sive et al., 2000; Kerr et al., 2008). Template DNAs for in vitro transcription were prepared by digestion, followed by transcription, with appropriate restriction enzymes and polymerases: trim36-pcmvsport6 (SalI/T7), nr3 (a gift from R. Harland, University of California-Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA; EcoRI/T7), eomes and myod (gifts from J. Gurdon, The Gurdon Institute, Cambridge, UK; EcoRI/T3 and BamHI/SP6, respectively), and sizzled (from M. Kirschner, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Addgene plasmid 16688, BamHI/T3). Antisense RNA probes labeled with digoxigenin-11-UTP (Roche) were synthesized using polymerases and reaction buffers from Promega.

Immunostaining

Whole-mount immunostaining for microtubules and cytokeratins was performed using previously described methods (Elinson and Rowning, 1988). Fluorescence was visualized on a Leica DMI3000B inverted microscope using a 63× dry objective (Leica Microsystems). Antibodies were α-tubulin mouse antibody, clone DM1A (ascites 1:200, Sigma) and cytokeratin mouse antibody, clone 1h5 (supernatant 1:5, DSHB). Secondary antibodies were goat anti-mouse conjugated with Alexa-488 or -564 (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) diluted in PGT (1×PBS, 1% goat serum, 0.5% Triton X-100; 1:500). Whole-mount staining for β-catenin was performed essentially as described (Schneider et al., 1996), using a rabbit anti β-catenin antibody (C2206, Sigma, 1:200).

For immunostaining of sections, samples were fixed and embedded in polyethylene glycol 400 distearate (PEDS wax, Polysciences) with 10% cetyl alcohol (1-hexadecanol), modified from Godsave et al. (Godsave et al., 1984). Sections were immunostained as described (Houston and Wylie, 2003). Tor70 (a gift from Richard Harland) was used at a 1:6 dilution; 12/101 (DSHB) was used at a 1:6 dilution. Detection was performed as described above. For histology, sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E).

Guinea pig Trim36 antibodies were raised against purified Xenopus Trim36 protein (Cocalico Biological). The trim36 CDS was cloned into the pDEST17 vector (Invitrogen) by Gateway recombination to generate a fusion protein N-terminally tagged with six histidines (6-His). Recombinant protein was produced in bacteria following the manufacturer's instructions, and refolded from inclusion bodies as described (Houston and King, 2000a). The 6-His-tagged Trim36 protein was then purified over a nickel column (His GraviTrap, GE Healthcare), eluted with 300 mM imidazole and dialyzed against PBS.

Ubiquitylation assays

Embryos were injected at the 2-cell stage with full-length or mutant trim36 mRNAs, HA-ubiquitin (a gift from S. Piccolo, University of Padua, Italy), or both (1 ng of each), and cultured to stages 9-10. Samples were lysed in cell lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA (pH 8.0), 1% Triton X-100, with protease and/or phosphatase inhibitors) and immunoprecipitated using Trim36 antisera. The resulting complexes were electrophoresed and immunoblotted as described (Yokota et al., 2003). Samples were blotted against HA-ubiquitin (mouse anti-HA clone 3F10, 1:500, Roche Applied Science) and against Trim36 (1:2000).

RESULTS

Trim36 is encoded by a vegetally localized mRNA in Xenopus

We set out to identify novel mRNAs localized to the vegetal cortex of Xenopus oocytes. To accomplish this, we isolated total mRNA from hand-dissected vegetal cortex pieces (Elinson et al., 1993) and intact whole oocytes, generated labeled cDNA and probed Affymetrix GeneChip arrays in duplicate. These data were analyzed for RNAs enriched in the cortex relative to the whole oocyte. The details and full results of this screen will be described elsewhere. We selected one of the most highly enriched genes from this screen for further functional analysis, tripartite motif-containing 36 (trim36; UniGene ID Xl.6926), which is enriched by ∼25-fold in the cortex compared with the whole oocyte (data not shown).

We verified the enrichment of trim36 in the cortex by RT-PCR (data not shown) and obtained a full-length EST through a commercial source. This full-length trim36 EST (from Xenopus laevis) encodes a cDNA of ∼4000 nucleotides (nt), with a 2200 nt coding region (CDS) preceded by several in-frame stop codons (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). Conceptual translation of the cDNA identified a methionine residue in a favorable initiation context and yielded a putative protein of 733 amino acids. Amino acid sequence analysis revealed characteristic domains classifying this protein as a member of the large tripartite motif-containing family (Trim), namely an N-terminal RING-finger domain followed by two B-box zinc-finger domains and a coiled-coil domain (reviewed by Meroni and Diez-Roux, 2005) (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). The C-termini of Trim proteins can include a variety of different functional domains, such as bromo- or NHL-domains, or in the case of Trim36, a B30.2/SPRY domain of uncertain function. Trim36 also contains a COS motif, which groups this protein within a subclass of Trim proteins that localize to microtubules (Short and Cox, 2006). Amino acid sequence alignments using the conceptual Trim36 protein sequence indicated strong similarity to human and mouse Trim36 proteins (also known as mouse Haprin, and human RBCC728 or RNF98; ∼75% identity) (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material) and revealed that it is 95% identical to the Xenopus tropicalis Trim36 protein. Comparisons across species using the Metazome database (http://www.metazome.com/) found that the Xenopus tropicalis trim36 gene occupies a conserved position with respect to surrounding genes compared to other tetrapods, suggesting orthology (data not shown).

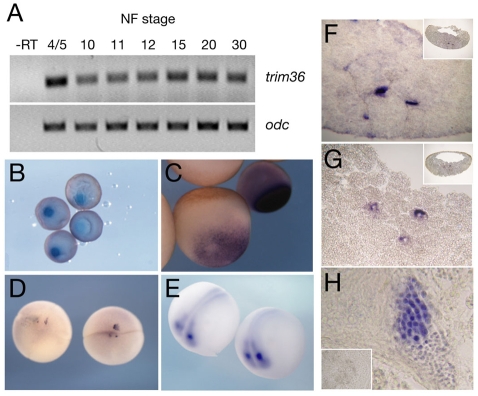

Analysis of trim36 mRNA expression during early development further confirmed its vegetal cortex localization and also showed that trim36 is enriched in the germ plasm of oocytes and early embryos. Temporally, trim36 is abundant maternally, but decreases throughout development, as assessed by RT-PCR (Fig. 1A). Spatially, trim36 mRNA is enriched in the mitochondrial cloud/Balbiani body of stage I oocytes (Fig. 1B), the origin of germ-plasm material (Heasman et al., 1984). In fully grown stage VI oocytes, trim36 is localized in a compact expression domain in the vegetal cortex (Fig. 1C). trim36 RNA was further detected in the germ plasm of fertilized eggs and 4- to 8-cell-stage embryos, clustered in yolk-free islands along vegetal cleavage furrows (Fig. 1D). During neurula stages, trim36 RNA is expressed outside the germ plasm in the developing neural tube and is enriched at the midbrain-hindbrain boundary (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Expression of trim36 in Xenopus. (A) RT-PCR for trim36 at different Nieuwkoop and Faber (NF) stages; `-RT' was processed in the absence of reverse transcriptase. ornithine decarboxylase (odc) was included as a loading control. (B-E) Whole-mount in situs using antisense trim36 probe. (B) Stage I oocytes, (C) stage VI (left) and stage IV (right) oocytes, (D) 4-cell embryos (vegetal view) and (E) neurula embryos (dorsal/anterior view). (F-H) In situs for trim36 on sections; insets in F and G are low-power views, inset in H is trim36 sense probe. (F) Stage 7 sagittal section, (G) stage 11 sagittal section and (H) adult testis.

In situ hybridization on sectioned blastulae and gastrulae revealed trim36 transcripts associated with the germ plasm during gastrulation, including perinuclear localization in stage 11 embryos (Fig. 1F,G), a hallmark of the germ plasm. trim36 RNA was undetectable in the primordial germ cells (PGCs) of post-gastrulation embryos, including migrating PGCs at the tailbud stage (data not shown). We also examined the testis, as mammalian trim36 homologs are implicated in acrosome function, and found robust trim36 staining in spermatogenic cells of the adult testis (Fig. 1H). Overall, our expression data show that trim36 is localized to the germ plasm of oocytes and early embryos, and is expressed in the developing nervous system and in adult germ cells.

Depletion of maternal trim36 causes reduced dorsal axis structures

Although the enrichment of trim36 in the germ plasm was suggestive of a role in PGC formation, other germ-plasm RNAs, such as wnt11 (Tao et al., 2005) and fatvg (Chan et al., 2007), have been implicated in dorsoventral axis formation. To examine the role of trim36 in early development, we injected antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (oligos) into full-grown oocytes to deplete maternal trim36 mRNA. We identified two different oligos against trim36, trim36-3 and trim36-4, that were effective in reducing trim36 mRNA in a dose-dependent manner. These oligos were synthesized in a phosphorothioate-modified form and used in maternal loss-of-function experiments. We generated embryos deficient in trim36 by transferring oligo-injected oocytes into egg-laying host females and fertilizing the recovered experimental eggs. Both oligos gave comparable results, but oligo trim36-3 gave the most consistent results and was used in the following experiments. A representative RT-PCR analysis of trim36 mRNA levels in control and oligo-injected oocytes is shown in Fig. 2A. The doses used in these experiments (3-4 ng trim36-3) typically depleted 80-90% of maternal trim36 mRNA.

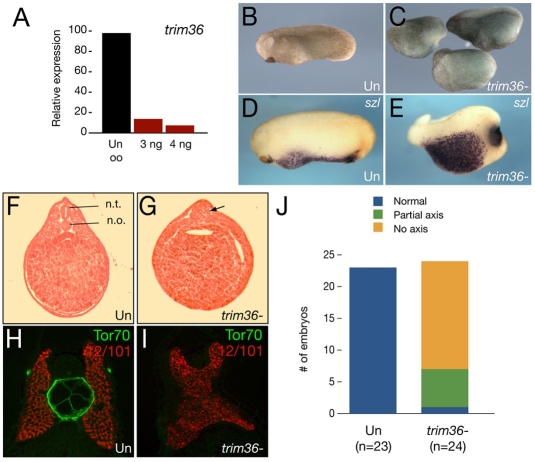

Fig. 2.

Depletion of maternal trim36. (A) Quantitative real-time PCR of trim36 expression in oligo-injected oocytes. Samples were normalized to odc levels and displayed as a percentage relative to the uninjected oocyte (Un oo) sample. Oocytes were injected with 3.0 or 4.0 ng of trim36-3 oligo. (B) Phenotype of an uninjected stage 24 embryo. (C) Phenotypes of sibling trim36-depleted embryos. (D) In situ hybridization of sizzled (szl) in an uninjected control embryo. (E) szl expression in a trim36-depleted embyro. (F) H&E-stained section of a control embryo, with the neural tube (n.t.) and notochord (n.o.) indicated. (G) H&E-stained section of a trim36-depleted embryo; notochord and neural tube are absent, and a somite muscle mass persists in the midline (arrow). (H,I) Notochord marker Tor70 (green) and somite marker 12/101 (red) in control (H) and trim36-depleted (I) embryos. (J) Histogram showing the distribution of phenotypes (see key) in trim36-depleted embryos (from two experiments).

Embryos derived from the fertilization of oocytes injected with oligos against trim36 developed normally up to gastrulation, but were then delayed in blastopore lip formation compared with embryos derived from uninjected sibling oocytes. These trim36-depleted embryos eventually completed gastrulation, but in the majority of cases failed to form neural plates and formed large cysts beneath the animal pole. By the late neurula and early tailbud stages, trim36-depleted embryos were radially ventralized in the extreme cases, or formed partial axes lacking anterior structures in the less severe cases (Fig. 2B,C). The effects of trim36 oligo injection were highly consistent over many experiments, resulting in ∼82% of injected embryos with ventralized phenotypes (80/98; 81.6%), compared with a very low incidence of ventralization in uninjected embryos (1/117; 0.9%). We counted the distribution of phenotypes in two experiments (Fig. 2J) and found that over two-thirds of the embryos with ventralized phenotypes were severely affected (no axis). The remaining embryos were less severely affected (partial axis), and only one embryo was unaffected in these two experiments. We confirmed the presence of excess ventral tissue by performing in situ hybridization on early tailbud-stage embryos for sizzled (szl) mRNA (Fig. 2D,E), a marker of belly tissue (Salic et al., 1997). In line with these results, trim36-depleted embryos also lacked well-formed neural tubes, somites and notochords, in some cases forming unorganized lumps of somite tissue in the midline (Fig. 2F,G). The absence of notochord in trim36-depleted embryos was verified by double immunostaining for notochord (Tor70 antibody) and somite (12/101 antibody) markers on sectioned embryos (Fig. 2H,I).

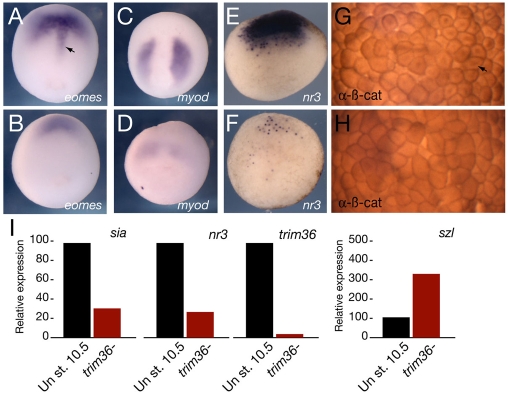

Since differentiated dorsal structures require signals from the organizer, we examined the extent of organizer specification in gastrula-stage trim36-depleted embryos using in situ hybridization and RT-PCR (Fig. 3). In trim36-depleted embryos, the notochord expression domain of eomesodermin (eomes) was lost (Fig. 3A,B), and the expression of myod, an early molecular marker for somites, was reduced (Fig. 3C,D). Organizer markers nodal-related 3 (nr3) (Fig. 3E,F) and noggin (not shown) were severely reduced in early gastrula-stage embryos. Since nr3 is a direct target of Wnt signaling in the early embryo (Smith et al., 1995), we also examined the dorsal stabilization of β-catenin directly by immunostaining. β-catenin was enriched in the dorsal nuclei of control embryos (Fig. 3G; see Fig. S2A,B in the supplementary material), whereas this staining was reduced or absent in trim36-depleted embryos (Fig. 3H; see Fig. S2C,D in the supplementary material). Consistent with these results, real-time RT-PCR analysis of gene expression in trim36-depleted embryos showed much reduced levels of direct Wnt target genes siamois and nr3, and a concomitant increase in szl expression, which is a ventral marginal zone marker at this stage (Fig. 3I). Furthermore, activity of the Wnt/β-catenin reporter, TOPflash, was reduced by ∼50% in trim36-depleted gastrulae, further supporting the deficiency in Wnt/β-catenin signaling at this stage (see Fig. S2E in the supplementary material).

Fig. 3.

Dorsal marker expression in trim36-depleted embryos. Dorsal genes and β-catenin protein in control (A,C,E,G) and trim36-depleted (B,D,F,H) embryos. (A,B) In situs for eomes in stage 12 embryos. Dorsal view, anterior is to the top. Arrow in A indicates eomes expression in the anterior notochord. (C,D) In situs for myod in stage 12 embryos. Dorsal view, anterior is to the top. (E,F) In situs for nr3 in stage 9.5 embryos. Vegetal view, dorsal is to the top. (G,H) Immunostaining for β-catenin in stage 8 embryos. Animal pole view of cleared embryos, dorsal is to the right. Arrow in G indicates nuclear β-catenin. (I) Quantitative real-time PCR of dorsal (sia and nr3) and ventral (szl) markers in control (Un) and trim36-depleted (trim36-) embryos at stage 10.5.

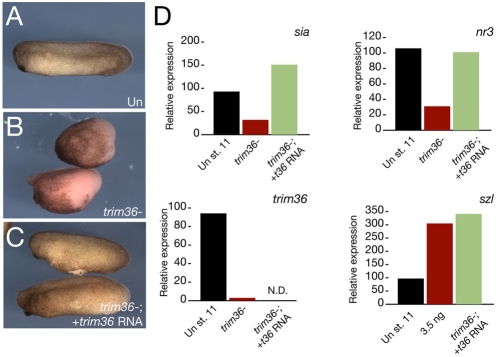

To confirm the specificity of these phenotypes, we injected a subset of trim36-depleted oocytes with trim36 mRNA prior to their maturation and fertilization. Injection of trim36 mRNA reduced the proportion of ventralized embryos to ∼35% (15/43; 34.9%; Fig. 4A-C). These rescued embryos also showed partial restoration of wild-type levels of organizer markers sia and nr3 at the gastrula stage (Fig. 4D). Ventral markers were not rescued, possibly owing to the complex and indirect regulation of ventral genes, sizzled in particular, by the organizer (Lee et al., 2006; Collavin and Kirschner, 2003).

Fig. 4.

Specificity of trim36 depletion. (A-C) Phenotypes of representative control uninjected (Un, A), trim36-depleted (trim36-, B) and rescued (trim36-; + trim36 RNA, C) embryos. (D) Quantitative real-time PCR of dorsal (sia and nr3) and ventral (szl) markers in rescue experiments (green bars). N.D., not determined.

Additionally, we obtained similar results using a translation-blocking morpholino oligo (see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material), providing further evidence for specificity. Because morpholinos do not target the degradation of mRNAs, we can argue against a structural role for trim36 RNA in axis formation, as has been suggested for other classes of localized RNAs (Kloc et al., 2005; Heasman et al., 2001). To summarize, these results show that trim36 is required, either directly or indirectly, for the stabilization of β-catenin and for Wnt target gene activation, leading to normal dorsal tissue formation in Xenopus.

Wnt/β-catenin signal transduction is not dependent on Trim36

We next tested the hypothesis that Trim36 might be required within the Wnt signal transduction cascade. Preliminary experiments showed that ubiquitous expression of high doses of trim36 (>300 pg) caused defects in embryo integrity, leading to disaggregation of the embryos during gastrulation and to epidermal lesions (see Fig. S4A,B in the supplementary material). Lower doses had no visible effect on development, and we failed to induce secondary axis formation by injecting trim36 into ventral vegetal blastomeres, a well-characterized effect of Wnt ligands and signaling molecules (data not shown). Trim36 was not sufficient to activate Wnt signaling in animal cap assays (see Fig. S4C in the supplementary material) and also failed to rescue β-catenin-depleted embryos (see Fig. S4D in the supplementary material).

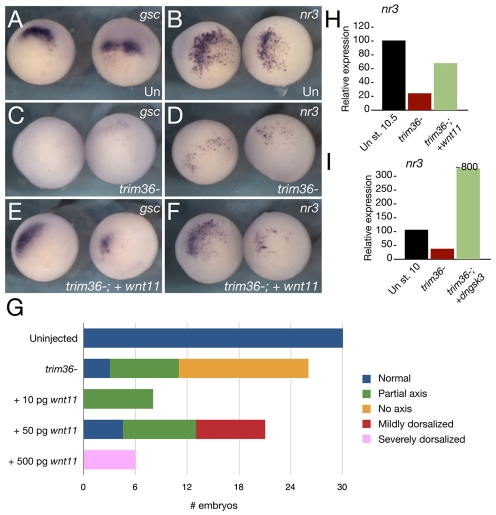

We next stimulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling in trim36-depleted embryos to determine the activity of Wnt ligands and effectors in the absence of trim36. Oocytes were injected with the trim36-3 oligo and were subsequently injected with wnt11 mRNA prior to host transfer and fertilization. The resulting embryos were analyzed at the gastrula stage for Wnt target gene expression by RT-PCR and in situ hybridization, and at the tailbud stage by phenotype comparisons. In at least three separate experiments, injection of wnt11 restored the expression of dorsal markers (gsc and nr3; Fig. 5A-F,H), as well as reducing the incidence of axis deficiency (Fig. 5G). Some embryos were mildly dorsalized at a moderate wnt11 dose, whereas higher doses caused severe dorsalization (see Fig. S5 in the supplementary material). wnt11 also rescued notochord formation in two out of three embryos examined by histology (see Fig. S5 in the supplementary material). Similar results were seen using wnt8 (data not shown) and dominant-negative gsk3β (dngsk3β; Fig. 5I), further supporting the idea that Trim36 acts upstream of Wnt pathway activation. The expression of dorsal markers could also be rescued by injection of the BMP antagonist noggin (see Fig. S6 in the supplementary material), which functions downstream of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, suggesting that other pathways controlling dorsoventral patterning are not affected by trim36 depletion. Overall, these data suggest that Trim36 is not required for Wnt/β-catenin signal transduction per se, but that it might lie upstream of or parallel to Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Fig. 5.

trim36-depleted embryos are rescued by wnt11 mRNA. trim36 was depleted by the injection of antisense oligos into oocytes and 50 pg wnt11 mRNA was injected prior to fertilization by the host-transfer method. gsc (A,C,E) and nr3 (B,D,F) expression in stage 10.5 embryos; (A,B) uninjected; (C,D) trim36-depleted (trim36-); and (E,F) trim36-depleted + 50 pg wnt11 mRNA (trim36-; + wnt11). (G) Histogram showing the distribution of phenotypes (see key) in uninjected embryos, trim-36-depleted embryos and trim36-depleted embryos rescued by wnt11 injection (from two experiments). (H,I) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of nr3 expression in control, depleted and rescued embyros injected with 50 pg wnt11 (H) or 1.0 ng dngsk3b (I) (green bars).

Trim36 is required for vegetal microtubule array formation and cortical rotation

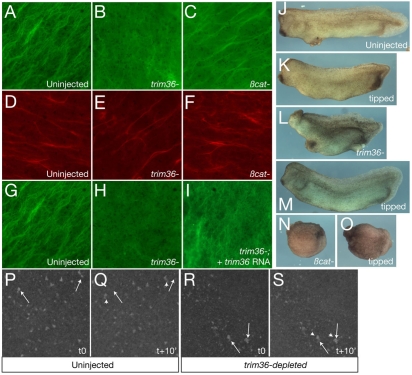

Since Trim36 and other Trim proteins with a COS motif associate with microtubules (Short and Cox, 2006), we investigated a possible role for Trim36 in microtubule function during cortical rotation. We generated trim36-depleted eggs through the host-transfer procedure and immunostained against α-tubulin at ∼80 minutes post fertilization, a time when robust microtubule arrays are present and cortical rotation is occurring (Elinson and Rowning, 1988). As controls, we included uninjected sibling oocytes, as well as β-catenin-depleted oocytes, which are also ventralized (Heasman et al., 1994) but should have normal cortical rotation. These controls showed robust, normal organization of microtubule arrays (Fig. 6A,C; ∼90% normal; n=30 for each). By contrast, trim36-depleted eggs either lacked microtubule organization completely or exhibited fragmented microtubules in a loose organization (Fig. 6B; 77% affected; n=22). As an additional control to ensure that trim36-depleted eggs were indeed activated and were otherwise developing normally, we stained for cytokeratin in the vegetal cortex. Cytokeratins form parallel arrays similar to microtubules upon activation (Klymkowsky et al., 1987) and, importantly, these arrays appear independently of microtubules (Houliston and Elinson, 1991). Consistent with this idea, we found that uninjected, β-catenin- and trim36-depleted eggs all exhibited normal cytokeratin arrays (Fig. 6D-F; 100% normal; n=16 for each). In a separate series of experiments, we tested the specificity of this microtubule effect by examining trim36-depleted eggs that were rescued by injection of trim36 mRNA. In these experiments, the incidence of aberrant or absent microtubules was reduced in rescued eggs (46% affected; n=15; Fig. 6I) compared with trim36-depleted siblings from the same experiment (74% affected, n=15; Fig. 6H), indicating that the disruption of microtubules is indeed specific to trim36 depletion.

Fig. 6.

Trim36 regulates vegetal microtuble formation and cortical rotation. (A-C) Immunostaining of microtubules at 80 minutes post fertilization in control (A, uninjected), trim36-depleted (B, trim36-) and β-catenin-depleted (C, βcat-) eggs. (D-F) Immunostaining of cytokeratin at 80 minutes post fertilization in control (D, uninjected), trim36-depleted (E, trim36-) and β-catenin-depleted (F, βcat-) eggs. (G-I) Immunostaining of microtubules at 80 minutes post fertilization in control (G, uninjected), trim36-depleted (H, trim36-) and rescued (I, trim36-; + trim36 RNA) eggs. Vegetal views are shown in A-I, viewed with a 63× objective. (J-O) Representative phenotypes of uninjected (J,K), trim36-depleted (trim36-; L,M) and β-catenin-depleted (βcat-; N,O) embryos. (J,L,N) Normal orientation, (K,M,O) tilted 90°. (P-S) Frames from time-lapse movies of cortical rotation in DiOC6(3)-stained eggs. Controls (P,Q) and trim36-depleted (R,S) embryos at time 0 (t0) and +10 minutes (t+10′). Arrows indicate the starting points of indicated germ-plasm islands, arrowheads indicate the final position of the same islands. Images were taken with a 10× objective.

We next examined the extent of cortical rotation more directly using time-lapse imaging. For simplicity, we made short time-lapse movies of prick-activated oocytes stained with DiOC6(3), which labels the mitochondria associated with the germ plasm and can be used to follow cortical rotation movements in living eggs (Quaas and Wylie, 2002; Savage and Danilchik, 1993). We treated uninjected and trim36-depleted oocytes with progesterone to induce maturation and 20 hours later we stained them with DiOC6(3) and prick-activated them. At 50 minutes after pricking, we collected images over 10 minutes from different eggs and assembled these into movies. In movies of uninjected eggs, the germ-plasm islands were seen moving across the oocyte (see Movie 1 in the supplementary material; Fig. 6P,Q shows individual frames), whereas in time-lapse videos of trim36-depleted eggs, germ-plasm islands remained stationary or moved slowly (see Movie 2 in the supplementary material; Fig. 6R,S shows individual frames). These results were seen in all of the videos of individual trim36-depleted eggs (n=4), from two separate experiments, demonstrating that normal cortical rotation does not occur in the absence of trim36.

Trim36 depletion is rescued by tipping/gravity

Inclining, or tipping, eggs by 90° can rescue the deficiencies in dorsal axis formation resulting from microtubule disruption during the period of cortical rotation (Scharf and Gerhart, 1980; Scharf and Gerhart, 1983). In order to determine whether the effect of trim36 depletion on microtubule array formation is sufficient to explain the loss of the dorsal axis, we tested whether orienting trim36-depleted eggs by 90° could rescue normal dorsal development. As controls, we included uninjected eggs and β-catenin-depleted eggs within the same host-transfer experiment. β-catenin depletion does not affect microtubule formation and is required for the ultimate outcome of cortical rotation; we thus expected that these eggs would remain ventralized following inclination. We further expected that if Trim36 were primarily required for microtubule polymerization, then tilting would be able to rescue dorsal development.

We obtained uninjected, trim36- and β-catenin-depleted eggs by host transfer and quickly sorted them into dishes containing Ficoll buffer. Eggs were then manually tipped 90° relative to the animal-vegetal axis and left in this position until the first cleavage. A subset of each experimental group was placed in the same Ficoll buffer without tipping. These untipped eggs developed as expected; resulting in normal uninjected embryos and ventralized trim36- and β-catenin-depleted embryos (10/12 and 8/8 ventralized, respectively; Fig. 6J,L,N). From two separate tipping experiments, we recovered a lower proportion of affected trim36-depleted embryos (3/9 ventralized; Fig. 6M) in the tipped group than in the untipped groups. Tipped β-catenin eggs remained ventralized (5/5 ventralized; Fig. 6O) and tipped uninjected eggs were normal (6/7 normal; Fig. 6K). As an independent marker for dorsal development, we scored for the presence of notochord in putatively rescued trim36-depleted embryos. Embryos were fixed at the tailbud stage, and H&E-stained sections were examined. Both tipped and untipped uninjected embryos had notochords, and tipped and untipped β-catenin-depleted embryos lacked notochords and somite tissue in each case (3/3 embryos sectioned in each case; data not shown). Untipped trim36-depleted embryos lacked notochords, as seen in earlier experiments. However, tipped trim36-depleted embryos had clearly distinguishable notochords in all of the embryos sectioned (n=3; data not shown). These data show that gravity-driven rearrangements in the egg are sufficient to restore the dorsal axis and notochord development in the absence of Trim36.

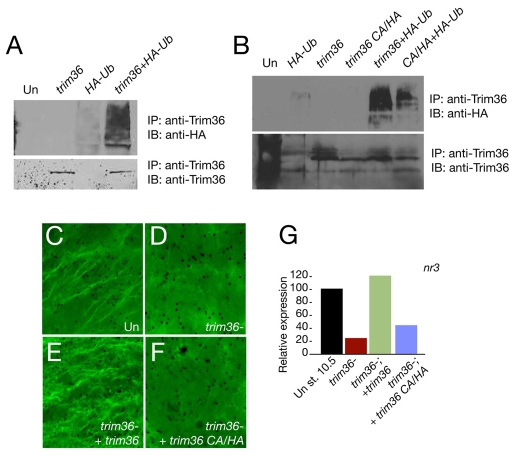

Trim36 ubiquitin ligase activity is required for microtubule polymerization

Many Trim proteins have ubiquitin ligase activity (Meroni and Diez-Roux, 2005), and this has recently been shown for human TRIM36 (Miyajima et al., 2009). To gain insight into Trim36 function, we asked whether Xenopus Trim36 has ubiquitin ligase activity and whether this activity is required for microtubule regulation. Since the putative substrates for Trim36 are unknown, we first tested the ability of Trim36 to catalyze its own ubiquitylation, a property of many ubiquitin ligases. Trim36 mRNA was overexpressed in embryos in the presence or absence of an mRNA encoding hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged ubiquitin. Trim36 protein was immunoprecipitated and the resulting complexes were immunoblotted with HA antibodies. We detected numerous high molecular weight bands in immunoprecipitates from co-injected embryos probed against HA-ubiquitin (Fig. 7A), indicating that ubiquitin conjugation had occurred. Blotting of the immune complexes with Trim36 antisera confirmed that equivalent amounts of Trim36 protein were recovered in each case (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Trim36 ubiquitin ligase activity is required to rescue the dorsal axis in trim36-depleted embryos. (A) Auto-ubiquitylation of Trim36. Immunoblotting of Trim36 immune complexes from lysates of control uninjected embryos (Un), trim36-injected embryos (1 ng trim36), HA-ubiquitin-injected embryos (1.0 ng HA-ub) or embryos injected with both trim36- and HA-ub. Top panel shows blotting using anti-HA, lower panel shows blotting using Trim36 antisera. (B) Trim36 CA/HA is deficient in auto-ubiquitylation. Immunoprecipitation and blotting as in A. (C-F) Immunostaining of microtubules at 80 minutes post fertilization. (C) Uninjected eggs (Un), (D) trim36-depleted eggs (trim36-) and (E,F) trim36-depleted embryos injected with either 200 pg wild-type trim36 RNA (E) or 200 pg trim36 CA/HA (F). (G) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of nr3 expression in control embryos, trim-36-depleted embryos and trim36-depleted embyros injected with wild-type trim36 RNA or with trim36 CA/HA RNA. Embryos in G are siblings of the embryos in C-F.

To determine the role of Trim36-dependent ubiquitin ligase activity during cortical rotation, we compared the ability of wild-type and ubiquitylation-deficient Trim36 forms to rescue the depletion of maternal trim36. The RING finger and B-box 2 domains have been implicated in mediating the substrate recognition and ubiquitin ligase activity of Trim proteins (Meroni and Diez-Roux, 2005). We made point mutations in conserved cysteine and histidine residues within the B-box 2 domain of Trim36 (C217A/H220A) that were implicated in the activity of a related Trim protein, Trim5α (Javanbakht et al., 2005). This mutant was inactive in gain-of-function assays. We confirmed that the C217A/H220A mutant was deficient in auto-ubiquitylation activity, as shown by a reduced amount of ubiquitin immunoprecipitated along with mutant Trim36 (Fig. 7B) compared with wild-type Trim36.

We next depleted oocytes of trim36 by antisense oligo injection, followed by rescue with either trim36 or trim36-C217A/H220A mRNAs. In two separate experiments, fertilized eggs rescued with wild-type trim36 showed normal microtubule array formation in at least half the cases, and had normal nr3 levels. By contrast, depleted embryos injected with trim36-C217A/H220A did not show either normal microtubule polymerization (Fig. 7C-F) or nr3 levels (Fig. 7G). Overall, these data suggest that the ability of Trim36 to ubiquitylate target proteins is necessary for the normal polymerization and alignment of microtubules during cortical rotation.

DISCUSSION

trim36 is localized to the germ plasm and encodes a ubiquitin ligase

We identified trim36 in a microarray screen for RNAs enriched in the vegetal cortex of Xenopus oocytes. The RNA for trim36 localizes to the mitochondrial cloud of stage I oocytes and is found in a pattern identical to that of germ plasm up to stage 11 of embryogenesis. Although we did not specifically address germ-cell formation in this study, it is possible that Trim36 also functions in specifying primordial germ cells. Targeted interference with Trim36 function in germ-plasm-containing cells could address these questions, although morpholino inhibition of zygotic Trim36 function disrupts morphogenesis and somite arrangement (Yoshigai et al., 2009), making the study of primordial germ cells problematic.

RING finger domain-dependent E3-ubiquitin ligase function is characteristic of Trim proteins (reviewed by Meroni and Diez-Roux, 2005). Our results, and those of a recent study on human TRIM36 (Miyajima et al., 2009), show that Trim36 has ubiquitin ligase activity both in vivo and in vitro, although the targets of Trim36 ubiquitylation have not yet been identified. Interestingly, a mutant Trim36 with substitutions in the B-box domain, which mediates substrate recognition, was unable to rescue dorsal axis formation, suggesting that Trim36 could not be recruited to the relevant protein complexes.

A subset of Trim proteins (including Trim36 and Trim18) contain a COS motif, which confers localization to microtubules (Short and Cox, 2006). Interestingly, TRIM18 mutations in Opitz syndrome patients result in the accumulation of PP2A in the microtubule fraction, leading to the dysregulation of microtubule dynamics (Trockenbacher et al., 2001). By analogy, Trim36 could regulate the microtubule-associated fraction of a protein involved in microtubule stability or organization, and potentially Wnt signaling.

Trim36 is required for cortical rotation and axis determination

Trim36-depleted embryos do not form a normal vegetal microtubule array, and do not undergo cortical rotation. These effects of Trim36 depletion can be rescued by re-orienting the eggs prior to the first cleavage by 90°, a treatment that overcomes the effects of UV irradiation. Our results thus suggest that Trim36 is not required for the synthesis of a component needed for dorsal axis formation. Furthermore, Wnt11 rescues trim36 depletion, ruling out a role for Trim36 in the regulation of the core Wnt/β-catenin signaling components.

It is intriguing that injection of Wnt11 into trim36-depleted oocytes, which would be expected to generate spatially unrestricted expression, results in the rescue of regional organizer gene expression and a single axis (Fig. 5). Wnt signaling induces a number of autoregulatory molecules, so it is possible that small differences in the abundance of injected Wnt could be regulated to result in a single active domain. Alternatively, Brown et al. (Brown et al., 1994) have shown that mature eggs have cryptic asymmetry, which could bias where the axis forms in the presence of a uniform signal. Taken together, our data suggest a model in which Trim36 is required to stabilize or align microtubules in the vegetal cortex region, resulting in the proper distribution of wnt11 mRNA and/or β-catenin stabilizing agents in the embryo.

Our results are reminiscent of data obtained by depletion of another germ-plasm-localized mRNA, fatvg (Chan et al., 2007), but with several important differences. fatvg-depleted embryos fail to undergo cortical rotation (microtubules were not examined) and exhibit stabilized β-catenin at the vegetal pole, which is essentially a phenocopy of UV irradiation (Darras et al., 1997; Medina et al., 1997). Our results differ, as we see an overall loss of β-catenin and Wnt target gene expression, in addition to a loss of cortical rotation. It is widely assumed that microtubules have a role solely in transporting dorsalizing molecules; however, our results suggest that the transport and activation of dorsalizing molecules might be closely coupled. A more thorough and consistent comparison of the phenotypic effects of disrupting microtubules and/or directional transport is needed to better understand how these processes are linked.

Is the role of Trim36 in axis formation conserved? The polymerization of microtubules at the vegetal pole of fertilized eggs has been observed in many chordate species (Eyal-Giladi, 1997). The Trim36 protein sequence is well conserved among vertebrates; however, our work is the first to describe its function in early development. It will be of interest to discover whether Trim36 has a wider role in early embryonic patterning, or whether it is required only in animals with cortical rotation. In either case, comparison of Trim36 function will help to better understand the complex problem of symmetry breaking in eggs.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://dev.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/136/18/3057/DC1

Supplementary Material

The authors would like to thank J. Gurdon, R. Harland and S. Piccolo for reagents; I. Dawid and S. Piccolo for discussions on ubiquitin ligases; and members of the Houston lab for critical reading of the manuscript. The monoclonal antibodies 12/101 and 1h5, developed by J. P. Brockes and M. Klymkowsky, respectively, were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB), developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA. This work was supported by The University of Iowa and by NIH grant 5R01 GM083999-02 to D.W.H. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Belenkaya, T. Y., Han, C., Standley, H. J., Lin, X., Houston, D. W., Heasman, J. and Lin, X. (2002). pygopus Encodes a nuclear protein essential for wingless/Wnt signaling. Development 129, 4089-4101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E. E., Margelot, K. M. and Danilchik, M. V. (1994). Provisional bilateral symmetry in Xenopus eggs is established during maturation. Zygote 2, 213-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A. P., Kloc, M., Larabell, C. A., Legros, M. and Etkin, L. D. (2007). The maternally localized RNA fatvg is required for cortical rotation and germ cell formation. Mech. Dev. 124, 350-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collavin, L. and Kirschner, M. W. (2003). The secreted Frizzled-related protein Sizzled functions as a negative feedback regulator of extreme ventral mesoderm. Development 130, 805-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darras, S., Marikawa, Y., Elinson, R. P. and Lemaire, P. (1997). Animal and vegetal pole cells of early Xenopus embryos respond differently to maternal dorsal determinants: implications for the patterning of the organiser. Development 124, 4275-4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinson, R. P. and Rowning, B. (1988). A transient array of parallel microtubules in frog eggs: potential tracks for a cytoplasmic rotation that specifies the dorso-ventral axis. Dev. Biol. 128, 185-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinson, R. P., King, M. L. and Forristall, C. (1993). Isolated vegetal cortex from Xenopus oocytes selectively retains localized mRNAs. Dev. Biol. 160, 554-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyal-Giladi, H. (1997). Establishment of the axis in chordates: facts and speculations. Development 124, 2285-2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart, J., Danilchik, M., Doniach, T., Roberts, S., Rowning, B. and Stewart, R. (1989). Cortical rotation of the Xenopus egg: consequences for the anteroposterior pattern of embryonic dorsal development. Development Suppl. 107, 37-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godsave, S. F., Anderton, B. H., Heasman, J. and Wylie, C. C. (1984). Oocytes and early embryos of Xenopus laevis contain intermediate filaments which react with anti-mammalian vimentin antibodies. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 83, 169-187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman, J., Quarmby, J. and Wylie, C. C. (1984). The mitochondrial cloud of Xenopus oocytes: the source of germinal granule material. Dev. Biol. 105, 458-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman, J., Holwill, S. and Wylie, C. C. (1991). Fertilization of cultured Xenopus oocytes and use in studies of maternally inherited molecules. Methods Cell Biol. 36, 213-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman, J., Crawford, A., Goldstone, K., Garner-Hamrick, P., Gumbiner, B., McCrea, P., Kintner, C., Noro, C. Y. and Wylie, C. (1994). Overexpression of cadherins and underexpression of beta-catenin inhibit dorsal mesoderm induction in early Xenopus embryos. Cell 79, 791-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman, J., Wessely, O., Langland, R., Craig, E. J. and Kessler, D. S. (2001). Vegetal localization of maternal mRNAs is disrupted by VegT depletion. Dev. Biol. 240, 377-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houliston, E. and Elinson, R. P. (1991). Evidence for the involvement of microtubules, ER, and kinesin in the cortical rotation of fertilized frog eggs. J. Cell Biol. 114, 1017-1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston, D. W. and King, M. L. (2000a). A critical role for Xdazl, a germ plasm-localized RNA, in the differentiation of primordial germ cells in Xenopus. Development 127, 447-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston, D. W. and King, M. L. (2000b). Germ plasm and molecular determinants of germ cell fate. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 50, 155-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston, D. W. and Wylie, C. (2003). The Xenopus LIM-homeodomain protein Xlim5 regulates the differential adhesion properties of early ectoderm cells. Development 130, 2695-2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston, D. W. and Wylie, C. (2005). Maternal Xenopus Zic2 negatively regulates Nodal-related gene expression during anteroposterior patterning. Development 132, 4845-4855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston, D. W., Kofron, M., Resnik, E., Langland, R., Destree, O., Wylie, C. and Heasman, J. (2002). Repression of organizer genes in dorsal and ventral Xenopus cells mediated by maternal XTcf3. Development 129, 4015-4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javanbakht, H., Diaz-Griffero, F., Stremlau, M., Si, Z. and Sodroski, J. (2005). The contribution of RING and B-box 2 domains to retroviral restriction mediated by monkey TRIM5alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26933-26940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageura, H. (1997). Activation of dorsal development by contact between the cortical dorsal determinant and the equatorial core cytoplasm in eggs of Xenopus laevis. Development 124, 1543-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, T., Cuykendall, T. N., Luettjohann, L. C. and Houston, D. W. (2008). Maternal Tgif1 regulates nodal gene expression in Xenopus. Dev. Dyn. 237, 2862-2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, K., Tanaka, H. and Nishimune, Y. (2003). Haprin, a novel haploid germ cell-specific RING finger protein involved in the acrosome reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 44417-44423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, K., Tanaka, H. and Nishimune, Y. (2005). The RING-finger protein haprin: domains and function in the acrosome reaction. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 6, 567-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloc, M. and Etkin, L. D. (1995). Two distinct pathways for the localization of RNAs at the vegetal cortex in Xenopus oocytes. Development 121, 287-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloc, M., Wilk, K., Vargas, D., Shirato, Y., Bilinski, S. and Etkin, L. D. (2005). Potential structural role of non-coding and coding RNAs in the organization of the cytoskeleton at the vegetal cortex of Xenopus oocytes. Development 132, 3445-3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klymkowsky, M. W., Maynell, L. A. and Polson, A. G. (1987). Polar asymmetry in the organization of the cortical cytokeratin system of Xenopus laevis oocytes and embryos. Development 100, 543-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofron, M., Klein, P., Zhang, F., Houston, D. W., Schaible, K., Wylie, C. and Heasman, J. (2001). The role of maternal axin in patterning the Xenopus embryo. Dev. Biol. 237, 183-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku, M. and Melton, D. A. (1993). Xwnt-11: a maternally expressed Xenopus wnt gene. Development 119, 1161-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. X., Ambrosio, A. L., Reversade, B. and De Robertis, E. M. (2006). Embryonic dorsal-ventral signaling: secreted frizzled-related proteins as inhibitors of tolloid proteinases. Cell 124, 147-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marikawa, Y., Li, Y. and Elinson, R. P. (1997). Dorsal determinants in the Xenopus egg are firmly associated with the vegetal cortex and behave like activators of the Wnt pathway. Dev. Biol. 191, 69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, A. P. and Moon, R. T. (1989). Ectopic expression of the proto-oncogene int-1 in Xenopus embryos leads to duplication of the embryonic axis. Cell 58, 1075-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina, A., Wendler, S. R. and Steinbeisser, H. (1997). Cortical rotation is required for the correct spatial expression of nr3, sia and gsc in Xenopus embryos. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 41, 741-745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meroni, G. and Diez-Roux, G. (2005). TRIM/RBCC, a novel class of `single protein RING finger' E3 ubiquitin ligases. BioEssays 27, 1147-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J. R., Rowning, B. A., Larabell, C. A., Yang-Snyder, J. A., Bates, R. L. and Moon, R. T. (1999). Establishment of the dorsal-ventral axis in Xenopus embryos coincides with the dorsal enrichment of dishevelled that is dependent on cortical rotation. J. Cell Biol. 146, 427-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyajima, N., Maruyama, S., Nonomura, K. and Hatakeyama, S. (2009). TRIM36 interacts with the kinetochore protein CENP-H and delays cell cycle progression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 381, 383-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaas, J. and Wylie, C. (2002). Surface contraction waves (SCWs) in the Xenopus egg are required for the localization of the germ plasm and are dependent upon maternal stores of the kinesin-like protein Xklp1. Dev. Biol. 243, 272-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salic, A. N., Kroll, K. L., Evans, L. M. and Kirschner, M. W. (1997). Sizzled: a secreted Xwnt8 antagonist expressed in the ventral marginal zone of Xenopus embryos. Development 124, 4739-4748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage, R. M. and Danilchik, M. V. (1993). Dynamics of germ plasm localization and its inhibition by ultraviolet irradiation in early cleavage Xenopus embryos. Dev. Biol. 157, 371-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf, S. R. and Gerhart, J. C. (1980). Determination of the dorsal-ventral axis in eggs of Xenopus laevis: complete rescue of uv-impaired eggs by oblique orientation before first cleavage. Dev. Biol. 79, 181-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf, S. R. and Gerhart, J. C. (1983). Axis determination in eggs of Xenopus laevis: a critical period before first cleavage, identified by the common effects of cold, pressure and ultraviolet irradiation. Dev. Biol. 99, 75-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S., Steinbeisser, H., Warga, R. M. and Hausen, P. (1996). Beta-catenin translocation into nuclei demarcates the dorsalizing centers in frog and fish embryos. Mech. Dev. 57, 191-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short, K. M. and Cox, T. C. (2006). Subclassification of the RBCC/TRIM superfamily reveals a novel motif necessary for microtubule binding. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8970-8980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sive, H., Grainger, R. M. and Harland, R. M. (2000). Early Development of Xenopus Laevis: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Smith, W. C., McKendry, R., Ribisi, S., Jr and Harland, R. M. (1995). A nodal-related gene defines a physical and functional domain within the Spemann organizer. Cell 82, 37-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol, S. Y., Klingensmith, J., Perrimon, N. and Itoh, K. (1995). Dorsalizing and neuralizing properties of Xdsh, a maternally expressed Xenopus homolog of dishevelled. Development 121, 1637-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumanas, S., Strege, P., Heasman, J. and Ekker, S. C. (2000). The putative wnt receptor Xenopus frizzled-7 functions upstream of beta-catenin in vertebrate dorsoventral mesoderm patterning. Development 127, 1981-1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Q., Yokota, C., Puck, H., Kofron, M., Birsoy, B., Yan, D., Asashima, M., Wylie, C. C., Lin, X. and Heasman, J. (2005). Maternal wnt11 activates the canonical wnt signaling pathway required for axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell 120, 857-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trockenbacher, A., Suckow, V., Foerster, J., Winter, J., Krauss, S., Ropers, H. H., Schneider, R. and Schweiger, S. (2001). MID1, mutated in Opitz syndrome, encodes an ubiquitin ligase that targets phosphatase 2A for degradation. Nat. Genet. 29, 287-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, J. P., Oster, G. F. and Gerhart, J. C. (1986). Kinematics of gray crescent formation in Xenopus eggs: the displacement of subcortical cytoplasm relative to the egg surface. Dev. Biol. 113, 484-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, C. and Kimelman, D. (2004). Move it or lose it: axis specification in Xenopus. Development 131, 3491-3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, C., Farr, G. H., III, Pan, W., Rowning, B. A., Wang, J., Mao, J., Wu, D., Li, L., Larabell, C. A. and Kimelman, D. (2003). GBP binds kinesin light chain and translocates during cortical rotation in Xenopus eggs. Development 130, 5425-5436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota, C., Kofron, M., Zuck, M., Houston, D. W., Isaacs, H., Asashima, M., Wylie, C. C. and Heasman, J. (2003). A novel role for a nodal-related protein; Xnr3 regulates convergent extension movements via the FGF receptor. Development 130, 2199-2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshigai, E., Kawamura, S., Kuhara, S. and Tashiro, K. (2009). Trim36/Haprin plays a critical role in the arrangement of somites during Xenopus embryogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 378, 428-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost, C., Torres, M., Miller, J. R., Huang, E., Kimelman, D. and Moon, R. T. (1996). The axis-inducing activity, stability, and subcellular distribution of beta-catenin is regulated in Xenopus embryos by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Genes Dev. 10, 1443-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost, C., Farr, G. H., III, Pierce, S. B., Ferkey, D. M., Chen, M. M. and Kimelman, D. (1998). GBP, an inhibitor of GSK-3, is implicated in Xenopus development and oncogenesis. Cell 93, 1031-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.