Abstract

Research examining how cultural factors affect adjustment of minority individuals would be strengthened if samples studied better represented the diversity within these populations. To recruit a representative sample of Mexican American families, a multiple step process was implemented that included sampling communities to represent diversity in cultural and economic conditions, recruitment through schools, the use of culturally attractive recruitment processes, conducting interviews in participants’ homes, and a financial incentive. The result was a sample of 750 families that were very diverse in cultural orientation, social class, and type of residential communities and similar to the census description of this population. Thus, by making culturally appropriate adaptations to common recruitment strategies it is possible to recruit representative samples of Mexican Americans.

Keywords: Community, culture, Mexican Americans, recruitment, sampling

The Surgeon General’s Report (Thompson, 2001) made it clear that culturally influenced lifestyles, beliefs, and practices affect people’s risk for health problems and how they respond when health problems occur. The Surgeon General’s report argued that programs and policies affecting ethnic minorities’ health can improve only by greatly expanding knowledge of when and how culture matters. Social scientists also have called for expanded research on culture to determine the generalizability of theories and interventions as well as to understand the specific needs of, and develop interventions for, minority groups (e.g., Chang & Sue, 2005; Hall & Maramba, 2001; Utsey, Walker, & Kwate, 2005). However, studies rarely have included sufficient numbers of minorities or immigrants to address questions about the role of culture in health, adjustment, or development. Furthermore, when samples have included sufficient numbers of immigrants or minorities, research designs rarely provided the opportunity for adequate analyses to identify and understand the role of culture (Cauce, Coronado, & Watson, 1998; Chang & Sue, 2005). In fact, the modal research design for studies on cultural issues compares an ethnic minority sample, usually English speaking, low-income inner city residents, to a middle-class European American sample and attributes any differences to cultural factors (Cauce, Coronado, & Watson, 1998; Gonzales, Knight, Morgan-Lopez, Saenz, & Sirolli, 2002).

The primary weakness of studies with such limited samples is that they represent only a select subgroup of the minority population and fail to represent the diversity within that group. For instance, although middle class families constitute a majority of almost every ethnic group, studies of minorities usually focus on low income families. Similarly, although immigrants who speak little or no English make up a significant portion of the population for many minority groups, most research on these groups is conducted exclusively in English. Results from such select samples may grossly misrepresent characteristics of the population of interest which is particularly important when studying cultural issues. Furthermore, results from studies with unrepresentative samples often imply that the minority group’s culture is somehow inferior (Cauce, Coronado, & Watson, 1998; Cauce, Ryan, & Grove, 1998) in part because such designs often confound ethnicity, culture, and social class (Mertens, 1998). To make progress in finding answers to critical questions related to culture, it is imperative that researchers implement methodological strategies specifically designed to identify if, when, and how much culture matters to families and individuals (Cauce, Coronado, & Watson, 1998; Chang & Sue, 2005; Mertens, 1998; Thompson, 2001). Many important questions about how culture matters require sampling designs and recruitment strategies (and other improvements beyond the scope of this paper) that generate samples that adequately represent the diversity within minority groups and make it possible to distinguish the effects of social class and culture, for instance, on adjustment. To illustrate the value of such methods, recruitment results are presented from a study of Mexican American families (Mexican American is used to refer to anyone of Mexican origin living in the United States.).

Culture, Families, and Child Development

Culture refers to the regularities of everyday life that people largely take for granted including language, belief system, values, and customs (e.g., LeVine, 1977; Rogoff, 2003). Enculturation is the socialization process of passing traditional cultural systems to the next generation (Gonzales et al., 2002). Immigrants and most ethnic minorities also experience a second socialization process known as acculturation, the process of learning about and adapting to the language, beliefs, practices, and lifestyles of the majority culture in which they are embedded. These seemingly competing processes of enculturation and acculturation occur simultaneously to influence individual and family adjustment. For example, evidence suggests that adhering to traditional ways sometimes may be beneficial to one’s well-being (i.e., valuing familism may protect Mexican American adolescents from behavior problems; Gil, Vega, & Dimas, 1994) but also may create stress (i.e., cultural differences between home and school may cause difficulty for immigrant children (C. Suarez-Orozco & Suarez-Orozco, 2001). Although acculturation to the host culture provides immigrants with some obvious benefits (e.g., better employment and easier integration into schools), the process may be stressful and contribute to problems (e.g., family conflict and delinquency; Szapocznik, Kurtines, & Fernandez, 1980).

The size and diversity of the Mexican American population is ideal for research on the role of culture in adaptation. In addition to being one of the largest and fastest growing minority groups in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001), Mexican Americans are tremendously diverse in cultural orientations. This population ranges from recent immigrants, often living in ethnic enclaves where there may be few pressures to acculturate to the host culture (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001), to later generations who are highly acculturated and residing in the full range of residential communities from ethnic enclaves to predominately Anglo, middle-class, suburban neighborhoods. Although Mexican Americans are overrepresented among those in poverty, they also are well represented among all levels of income, education, and occupation.

Design Decisions

The types of research questions that stimulated the current study and the search for ways to obtain more representative samples of Mexican Americans included: Is the level of adherence to traditional values related to family functioning or mental health? Do differences between parents and children in rates of acculturation contribute to family conflict and influence mental health or school success? The commonly used cross-ethnic comparative research design that would entail samples of both Mexican American and European American families generally is not appropriate for these types of question. First, because Mexican Americans are more likely than European Americans to be low-income, ethnicity and social class often are confounded. Although participants can be matched on social class, even a perfect matching effort may not solve the problem because all adaptations, including adjustments to poverty, are culturally influenced (Harrison, Wilson, Pine, Chan, & Buriel, 1990). Therefore, the use of matching or statistical controls may mask group differences that represent cultural adaptations to economic conditions instead of revealing patterns attributable to culture.

Furthermore, when a comparative design is used, diversity within each group is usually neglected in favor of between group differences in means or slopes; the experiences of those who differ substantially from the group mean are likely to be overlooked. For example, middle class Mexican Americans whose families have been in the U.S. for many generations may be as acculturated to the U.S. mainstream, and as little acquainted with Mexican culture, as middle class European Americans. Additionally, samples in studies of Mexican Americans rarely are as diverse as the general Mexican American population in either acculturation/enculturation level (i.e., most studies include only English speakers) or social class (i.e., most samples are predominantly low-income). Thus, the best approach to resolving these and other issues may be to examine heterogeneity in adherence to culturally related phenomena and outcomes within an ethnic group, an ethnic homogenous (not to be confused with culturally homogenous) design that selects samples that represent the diversity within the population (Cauce, Coronado, & Watson, 1998; Mertens, 1998).

Using an ethnic homogenous design will not, by itself, remove all barriers to answering questions about the role of culture in adaptation. Researchers also need to use sampling plans appropriate to their research goals. Examinations of sampling and recruiting among minority populations focus almost exclusively on how to increase the numbers recruited, not on the qualities of samples obtained (e.g., Hall & Maramba, 2001; Maxwell, Bastani, Vida, & Warda, 2005). To focus on the role of culture in health or child adaptation, the way researchers define a Mexican American family becomes important to the quality of the sample. For instance, a common phenomenon among immigrant groups is that they marry members of other ethnic groups at rates that increase with each generation (e.g., Rosenfeld, 2002). Bi-ethnic marriages present quantitative researchers interested in questions about cultural influences with considerable challenges in both ethnic comparative and within group designs because these marriages almost invariably result in cultural blending. Each partner brings the cultural influences of their respective heritages into the marriage. The marital relationship as well as childrearing will be shaped by each couple’s unique blending of these cultures. How does one begin to distinguish the cultural influences of parents and extended family members from different ethnic groups? Bi-ethnic families represent an interesting social phenomenon and developmental context for children. At the same time, bi-ethnic unions may represent too great a challenge at this time for quantitative researchers interested in cultural influences on adjustment.

To deal with the complexities that bi-ethnic families represent, quantitative researchers studying cultural issues have three options. The first and most commonly adopted option is to ignore the issue when sampling, conducting analyses, or interpreting results. If bi-ethnic families represent a significant portion of the sample and their presence is ignored in analyses, results are likely to be biased and misinterpreted. A second option is possible in studies with very large samples: sufficiently large subgroups of the most common configurations of bi-ethnic marriages can be recruited. Even with very large samples, studies utilizing this option probably would have to ignore many other types of bi-ethnic marriages because of their small numbers in the general population and the costs of adding sizable subgroups of each. This option adds to the difficulty and expense of the sampling process and represents a variation of the comparative research design that likely oversimplifies the complexities of bi-ethnic families.

A third option for handling bi-ethnic families is to exclude them from samples. Until researchers learn more about such families and how to quantify what bi-ethnic families represent culturally (e.g., how much each partner’s culture contributes to family processes and childrearing), interpreting results of quantitative studies that include such families represents a monumental challenge. Simplifying the research process by excluding such families improves the likelihood that the interpretation of cultural effects will be relatively valid because bi-ethnic families represent a relatively small portion of the Mexican American population. Thus, for the time being it may be best to limit participation to families in which both marital partners are of Mexican origin. Using similar reasoning, researchers may want to consider limiting single parent families in such studies to those in which the missing biological parent is Mexican American and no step-parent of another ethnic background is present. Even when a non-Mexican heritage biological parent is not actively part of the child’s life, there is the possibility that extended family members of the missing partner contribute to the socialization of the child and thus contribute to a blended cultural environment. Similar cultural socialization and blending issues are introduced when a non-Mexican origin step-parent enters the family. With appropriate sampling criteria, the cultural adaptation process can be more precisely quantified and studied with a relatively small threat to the external validity of the findings. Although systematically excluding any portion of the target population results in a sample that cannot be perfectly representative of the target population, the choice is between a perfectly representative sample that will produce results subject to multiple interpretations and a sample that affords the opportunity for less ambiguous interpretations.

After deciding on a within group design and how to deal with bi-ethnic families, several factors need to be considered in order to obtain a sample that represents the diversity among Mexican Americans. First, the ethnic make-up of communities is related to the amount of support families receive for their cultural values, traditions, and practices as well as how much pressure they experience to acculturate to the host culture (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001). Thus, it is important to include diverse communities in the sampling process to represent influences from varied enculturation and acculturation pressures. Furthermore, if researchers wish to study the influence of different types of communities on Mexican Americans’ cultural experiences and adaptations, the sampling process needs to accommodate the requirements of multilevel data analysis (i.e., participants nested in communities). That is, the sampling design will need to include a sufficient number of communities to provide adequate power for analyses at that level and a sufficient number of participants within each community to adequately represent those communities (Roosa, Jones, Tein, & Cree, 2003). Representing the range of residential communities also should contribute to obtaining a sample that is more diverse in terms of income, generation status, and community quality than is commonly found in the literature.

Second, researchers need to use recruitment processes with high response rates. There is no evidence that Mexican Americans, in general, are more difficult to recruit than European Americans (Cauce, Ryan, & Grove, 1998). However, recruitment rates tend to be lower for both low-income families and those in urban areas (e.g., Capaldi & Patterson, 1987; Spoth, Goldberg, & Redman, 1999), two categories in which Mexican Americans are overrepresented. Low-income individuals may be less familiar with research and its possible benefits, may be more likely to be suspicious of the motivation of researchers and, therefore, may be less willing to participate than middle income populations (Yancey, Ortega, & Kumanyika, 2005). An additional consideration when working with Mexican Americans is the large number of immigrants who may be undocumented and apprehensive when contacted by strangers asking for personal information. These concerns may be at least partially overcome (a) if the research team has a long and positive relationship with the targeted group, (b) by affiliating with widely recognized and trusted individuals or institutions in the minority community (Cauce, Ryan, & Grove, 1998), (c) by associating the study with culturally attractive labels or symbols, (d) by emphasizing the potential contributions of research to the minority community (i.e., emphasizing the collective good), and (e) by offering an incentive commensurate with the time and effort demands of participation (Capaldi & Patterson, 1987; Dumka, Lopez, & Jacobs Carter, 2002; Harachi, Catalano, & Hawkins, 1997; Yancey et al., 2005). Another consideration when working with immigrants is the need to have all research materials translated into the native language.

Additionally, treating potential participants in a culturally sensitive manner can help break down barriers (Dumka et al., 2002; Yancey et al., 2005). For Spanish speakers this includes using the formal “usted” instead of the informal “tu” in all communication as a sign of respect. It also means acknowledging traditional family power structures. For example, a wife may be reluctant to agree to participate in research if her husband is not present to concur; if a wife does consent for herself, the family, or a child to participate without consulting her husband, he may reverse the decision to reassert his authority. Finally, personal contact may be particularly effective for recruiting low-income or minority populations (Cauce, Ryan, & Grove, 1998; Dumka, Garza, Roosa, & Stoerzinger, 1997; Gillis et al., 2001; Maxwell et al., 2005). Personal contact and showing respect are consistent with traditional Mexican values that emphasize the importance of personal relationships and showing deference toward the elderly or those in authority (Skaff, Chesla, Mycue, & Fisher, 2002). Hiring bilingual and bicultural staff with extensive experience with the target population makes it easier to be culturally sensitive and to establish trust with Mexican Americans (Yancey et al., 2005).

Given these considerations, the current study’s primary sampling goal was to obtain a sample that represented the diversity of the Mexican American population on acculturation, social class, and cultural/ecological niches. To accomplish this goal, a multi-stage procedure was implemented that included identifying the range of community contexts inhabited by Mexican Americans, using both systematic and purposive sampling to select communities, and selecting and recruiting families from within each community.

Methods

Reducing Resistance to Recruitment and Participation

Members of the research team cumulatively had several decades of experience conducting research in Mexican American communities in a southwestern city and, through this process, had developed positive relations with several communities as well as with several school districts that served this population. However, in a large metropolitan area this reputation only reaches a small portion of the larger community. Therefore, a group of prominent individuals closely connected to the local Latino and education communities were recruited to serve on an advisory board. These leaders facilitated access to various parts of the community and provided critically important advice on all aspects of the project. In addition, most research staff were bilingual, bicultural, and Latino and all had grown up in Latino communities and/or had extensive experience working with Latinos. Finally, the study was called The Family Project (Proyecto La Familia or simply La Familia) and its purpose was to collect information on normative development and guide the development of interventions to assist Mexican American families and children having difficulties. The project name and explanation appealed to Mexican Americans’ strong commitment to the family and to the larger Mexican American community.

In addition, schools were used as the access point for recruitment because Mexican American parents, particularly immigrants, highly value education (Fuligni, 2001). Furthermore, schools and school authorities are generally respected and trusted by Mexican American parents. By partnering with schools, the project gained credibility with most families. Partnering with schools, though, can be a liability in schools that have poor relations with minority families. In addition, recruiting Mexican Americans through schools may be an effective strategy only before junior high school when the drop out rate accelerates and those in school become less representative of the larger population.

Sampling Diverse Community Contexts

To identify culturally diverse communities, a procedure was developed for scoring the degree to which communities likely supported traditional Mexican values and lifestyles. A pilot study using qualitative observations was conducted throughout the city to identify indicators of community support for traditional values and lifestyles. One result of the pilot study was that there were few distinct indicators of support for traditional values and lifestyles available for small geographic units (e.g., blocks, block groups, census tracts). Therefore, community was defined by the attendance boundaries of public elementary schools, a geographic unit which contained sufficient indicators. The team identified 237 potential communities for inclusion in the study by finding all public schools in the metropolitan area with at least 20 Latino students in fifth grade, the target age group. The cutoff of 20 Latino students was used to increase the likelihood that at least 20 Mexican American families could be recruited over a two year period to adequately represent each community. Previous studies indicated that 30% – 40% of local Latino families would not be Mexican American, others would not meet other selection criteria, and some would refuse to participate.

Next, the cultural context of each of these communities was scored. Cultural context was defined as the degree to which a community could provide support for parental enculturation efforts, if any occurred. Cultural context was operationalized using multiple indicators: (a) Mexican American population density; (b) percent of elected and appointed office holders who were Latino; (c) the number of churches providing services in Spanish; the relative access within the community to traditional foods, medicines, and household items via (d) non-chain community stores (This part of the community score was based on the availability of specific traditional foods and household items [the list is available from first author] not merely the presence of community stores) and (e) traditional Mexican-style stores (e.g., carnicerías). The score from each indicator was standardized and summed to create a community cultural context score. Next, the 237 school communities were arranged from lowest score to highest (i.e., from little support for Mexican culture to high levels of support). The five “outliers” on the high end of the scale were selected because they represented particularly interesting living contexts (Mexican ethnic enclaves). Next, 25 additional schools were systematically selected from the remainder of this list by choosing a random starting point within the 10 lowest scores and selecting every 9th score (school) thereafter to represent the complete spectrum of community contexts.

Additional steps were taken to ensure that the sample of communities was representative of the range of living contexts experienced by Mexican Americans and that there were enough families to adequately represent the various community contexts. First, to avoid bias by restricting the sample to public schools in a city with about 200 private and charter schools, six private and charter schools were identified within the selected school communities. Only three of these alternative schools had Latino children in fifth grade and two of them had less than five Latino students. The research team was able to develop a partnership with one of these three schools, the one with the largest Latino enrollment. This alternative school and the public school in whose community it was located were treated as a single community. Second, after discovering that adult participants from the first year of the study were overwhelmingly (>75%) immigrants with low average levels of education, other schools were selected to diversify the acculturation level and social class of the sample. Based on recommendations of the Advisory Board, eight Catholic schools were selected from parts of the metropolitan area where more acculturated or middle class Latino families resided. Third, two selected schools had low enrollments of Latino fifth graders (less than 20), despite reporting higher enrollments in previous years. To adequately represent these communities, another school in a contiguous community with a very similar community cultural score was selected and paired with each of these schools for sampling purposes. Finally, one selected school produced an unusually low recruitment rate. To obtain more families from this type of community, a contiguous school with a very similar community cultural context score was recruited.

Additional schools were added to the sample because of changes in selected schools. Subsequent to implementing the sampling process, three schools each split into two separate but neighboring schools because of population growth. These split-pairs were treated as single communities. In another instance, a school that was K-6 in Year 1 of recruitment, switched to K-Sampling 4 in Year 2. In Year 2 families were recruited from the nearby school where the fifth grade students were sent and these two schools were treated as a single community. In total, 47 schools from 18 districts, the Catholic Diocese, and alternative schools were selected and organized into 42 distinct, non-contiguous communities. All public and Catholic schools selected agreed to participate in the project while one of three alternative schools selected agreed to participate. The communities sampled ranged from semi-rural to suburban to urban to inner city.

Family Sampling and Recruitment

The family recruitment process involved sending materials home with each fifth grade student in participating schools regardless of ethnicity. This packet included a letter from the principal and a brochure, each in English and Spanish, that explained the project and asked parents to indicate on a response form whether they were interested in learning more about the study and, if so, to provide contact information. To improve the return rate for the forms and to get teachers excited about and engaged in the process, two incentives were used: (1) a pizza party was given to every classroom with an 80% or higher return rate, or to the classroom with the highest return rate in each school if no classroom reached 80%, regardless of whether responses were positive or negative: (2) teachers received a $25 gift certificate if their class had the highest return rate in their school. For schools with large Latino enrollments, this process was used for one year; for others, this process was used for two consecutive years. Next, families who identified as Latino or those with Latino surnames were selected for screening. When there were more than 60 interested Latino families from a school, families were randomly selected for recruitment; in smaller schools, all interested Latino families were recruited. For families with multiple fifth graders, one was randomly selected before screening.

Trained bilingual and bicultural recruiters called families to screen them for eligibility based on these criteria: (a) the child was still attending a participating school; (b) the child lived with her/his biological mother who was Mexican American; (c) the child’s biological father was Mexican American; (d) no step-father or mother’s boyfriend was living with the child; (e) the child was not severely learning disabled; and (f) the family was not currently in related studies. These criteria were chosen to avoid having small numbers of less common family types (e.g., bi-ethnic families, step-families) that could not be examined separately in analyses. Controlling for family structure and cultural background during recruitment would aid in interpreting and generalizing results.

Once a family was ruled eligible, they were scheduled for an interview. At the scheduled time, one interviewer per participating family member (i.e., 2–3 interviewers) met the family at their home. Rarely, interviews were conducted at the child’s school when parents were concerned about having the interview in their homes (e.g., when sharing a home with others). Conducting interviews in participants’ homes eliminated problems due to lack of transportation and unfamiliarity with university settings. After introductions, an interviewer gave parents consent forms and assent forms to the child and read each aloud while participants followed along on their copies. These forms and all interview questions were read aloud to control for variability in literacy. The description of the study in the consent form was:

The Program for Prevention Research at Arizona State University is carrying out a research study to examine school, neighborhood and family influences on a child’s success. This study is being done in cooperation with your child’s school. ASU will use the information we get from this study to develop programs to help families and children throughout the community.

Your family will be asked questions about your feelings, experiences and attitudes about your community, your family, and your child’s school. Because this is a study of how children develop, we will contact you again in two years for follow up interviews to see how things have changed since this first interview. In fact, we hope to be able to follow the development of all children in this study for several years. However, you will have the right to agree to take part in the study, or refuse to take part in it, each time we contact you. The interview will last about 2 ½ hours for each of you. Your family will be paid $45 per person for taking part in this first interview.

All research materials were available in English and Spanish and the computer assisted personal interviews were programmed to make it possible to switch between languages as needed to help those, usually somewhat bilingual children, whose working vocabulary was split across languages. Most interviewers were fluently bilingual; English-only interviewers were assigned to cases only when the screening process indicated that there was no possibility that Spanish would be needed. If a family canceled a scheduled interview, they were given two additional opportunities to participate before being dropped from consideration. These “soft refusals” are not uncommon among this population and fit with traditional Mexican cultural values of respect; families did not want to say “no” to authority figures such as research personnel. Each family member was given their cash incentive immediately after signing a consent or assent form so that it was clear that they could keep the incentive even if they quit the study. Cash is preferred by low-income adults because they often do not have bank accounts and have to pay a fee to cash a check. Undocumented immigrants sometimes do not have identification that banks or check cashing services require. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board and conformed to APA ethical standards.

Other Methods and Procedures

To place the sampling and recruitment procedures into context, other aspects of the methods and procedures are summarized briefly. This study used a longitudinal design that included parent and child interviews when children were in grades 5 and 7. Interviews covered such constructs as parenting behavior, parent-child relationship quality, marital quality, stressors experienced and perceptions of the quality of community and school. To assess culture, parents and children completed measures of cultural values, ethnic identity, ethnic pride, cultural socialization, and the degree to which participants used English and Spanish. Data from school principals and teachers described children’s classroom behavior and academic performance and the degree to which schools were supportive of Mexican culture.

Results

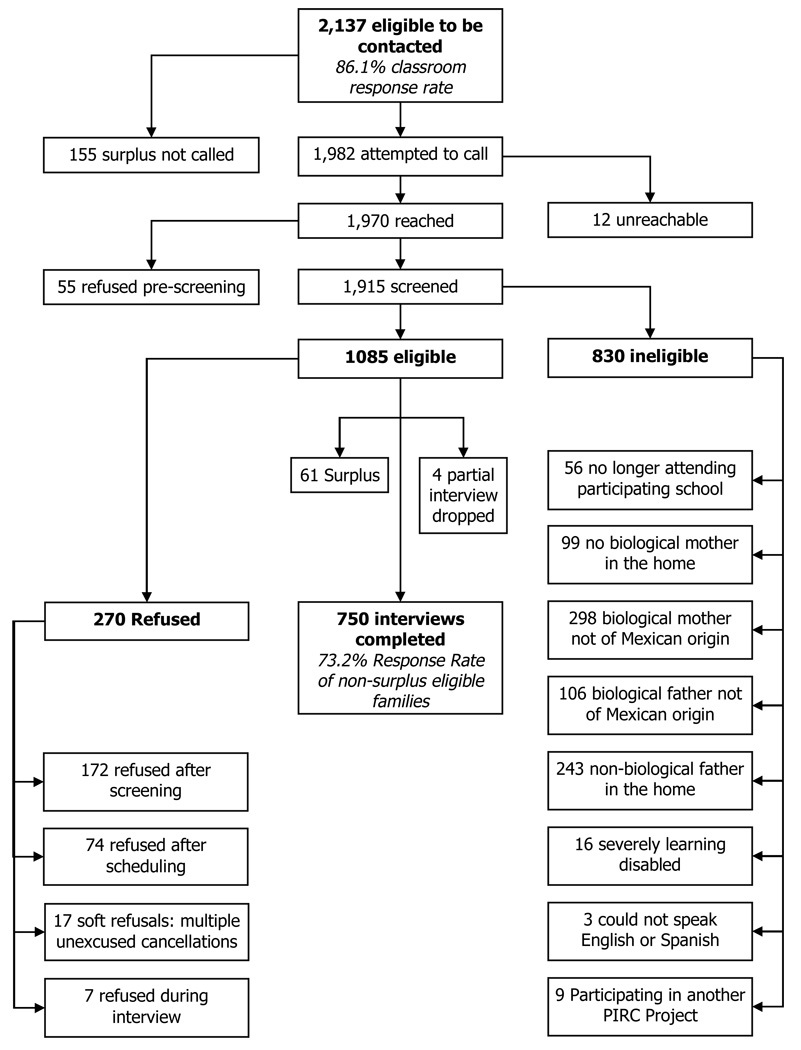

With an average response rate (i.e., forms returned) of 86.1% to classroom recruitment, 2,137 families from several ethnic groups indicated interest in the study although recruitment materials stated that only Latino families were sought. After screening, 1,085 families met criteria for participation, 830 were ineligible, 12 could not be contacted, 55 refused before eligibility could be determined, and 155 were not screened because quotas for their children’s schools were reached before they were screened (Figure 1). Of the 830 ineligible families, 56 cases were ineligible because the child no longer attended a participating school, in 99 cases the biological mother was not in the home, in 404 cases at least one parent was not Mexican American, in 243 cases a non-biological father figure was in the home, in 16 cases the child had a serious learning disability, in 3 cases there was a language barrier (i.e., spoke an indigenous dialect), and in 9 cases families were already participating in related studies. From the 1,085 eligible cases, 750 families (73.2%) completed interviews; this rate was over 70% for both English and Spanish speakers. The targeted sample size was reached before 61 cases could be scheduled and in 4 cases families terminated interviews before completion. A total of 270 eligible families that initially agreed to participate later refused; 172 cases refused before scheduling, 74 refused after scheduling, 17 were considered “soft refusals” after multiple unexcused cancellations of interview appointments, and 7 refused during the interview.

Figure 1.

Response rate throughout the recruitment and interviewing processes.

Parents who participated in this study overwhelmingly were born in Mexico, described themselves as “Mexican,” and preferred to speak Spanish. In contrast, a majority of children were born in the United States, overwhelmingly described themselves as “Mexican American,” and preferred English (Table 1). Although Mexican Americans are commonly described as having little education, over 25% of both mothers and fathers in this sample had some education beyond high school. Almost all fathers, and nearly two-thirds of the mothers, were employed. About two out of five families had incomes less than $25,000, about two-fifths had incomes between $25,001 and $50,000, and almost one-fifth had incomes above $50,000. When compared to census data for the metropolitan area (U. S. Census, 2000), this sample was reasonably similar to the local Mexican American population in terms of parent education, father’s employment status, income, and children’s language. On the other hand, mothers were more likely to be employed and parents were more likely to have been born in Mexico than one would expect from the Census. The largest discrepancy between the sample and Census data was in language use which may be due partially to differences in indicators (i.e., language used in the interview versus self report ratings of language ability, respectively).

Table 1.

Individual and family characteristics as a percent of the sample (Census data in parentheses).

| Variable | Mother (n=750) |

Father (n=466) |

Child (n=750) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Identity | |||||||

| Mexican | 77.2 | 71.0 | 41.0 | ||||

| Mexican American | 22.8 | 29.0 | 59.0 | ||||

| Nativitya | |||||||

| Mexico | 74.2 | (38.2) | 80.0 | (44.2) | 29.7 | ||

| United States | 25.8 | (61.8) | 20.0 | (55.8) | 70.3 | ||

| Language Preferenceb | |||||||

| English | 30.2 | (52.7) | 23.2 | (52.7) | 82.5 | (70.0) | |

| Spanish | 69.8 | (48.3) | 76.8 | (48.3) | 17.5 | (30.0) | |

| Education Completeda | |||||||

| 8th Grade or less | 29.2 | (30.7) | 30.2 | (33.4) | |||

| Some high school | 19.5 | (20.9) | 22.4 | (22.6) | |||

| 12th grade | 23.1 | (22.5) | 20.9 | (20.7) | |||

| Some college/vocational training | 22.0 | (19.2) | 20.2 | (17.1) | |||

| Bachelors or higher | 6.2 | (6.8) | 6.2 | (6.2) | |||

| Employment statusc | |||||||

| Employed | 63.6 | (46.6) | 96.6 | (97.1) | |||

| Unemployed | 11.2 | (3.5) | 3.5 | (2.9) | |||

| Housewife | 25.2 | ||||||

| Family Income | Sample | ||||||

| $25,000 or less | 44.3 | (37.1) | |||||

| $25,001 –$50,000 | 38.1 | (36.1) | |||||

| Greater than $50,000 | 17.6 | (26.8) | |||||

| Family Structurea | |||||||

| Single mother family | 24.0 | (18.6) | |||||

| Two parent family | 76.0 | (70.9) | |||||

Census data is for all females or males and not limited to parents or adults in our age group

The most comparable census data for mothers and fathers is all adults 18 and up and for children 15–17 year olds

Census data is for all females, not just mothers, while the male data is limited to husbands

Children in this study attended fairly segregated schools with more than one-half enrolled in schools with at least 75% of the student body being Latino (Table 2). On the other hand, almost one-third of the students were distinct minorities in their schools. Similarly, most children attended economically segregated schools with over 60% in schools in which at least 75% of the students qualified for free school lunch, an indicator of poverty level. However, participating families lived in quite diverse neighborhoods. Less than one-fifth lived in ethnic enclaves with Latino densities above 50%. Only about one-fifth lived in neighborhoods in which more than one-half of the families were living below the poverty level.

Table 2.

School and neighborhood characteristics as a percent of the sample.

| Latinos in Student Body | |

| 25% or less | 3.7 |

| 25.1% to 50% | 28.1 |

| 50.1% to 75% | 14.2 |

| 75.1% to 100% | 54.0 |

| Students Eligible for Free/Reduced School Lunch | |

| 25% or less | 2.8 |

| 25.1% to 50% | 9.1 |

| 50.1% to 75% | 19.7 |

| 75.1% to 100% | 68.4 |

| Mexican American Population Density | |

| 25% or less | 36.6 |

| 25.1% to 50% | 43.9 |

| 50.1% to 65% | 19.5 |

| Families Living in Poverty | |

| 25% or less | 9.5 |

| 25.1% to 50% | 70.2 |

| 50.1% or higher | 20.3 |

Thus, the sample obtained was quite diverse on multiple characteristics. Was it necessary to include the first step in the sampling process, sampling diverse communities, to achieve this level of sample diversity? One way to answer this question is to examine intraclass correlations (ICCs) for key study variables. ICCs represent the degree to which there is more variability between units (e.g., communities) studied than within these units; non-significant ICCs indicate that there is more variation within a unit than between units. For indicators of social class (e.g., parent education and family income), ICCs were significant and ranged from .08 to .34. For parent reports of neighborhood quality, ICCs were significant and ranged from .13 to .16. For measures of parent and child use of English and Spanish, ICCs ranged from .03 (child use of English) to .19 with only the measure of child’s use of English being nonsignificant (over 80% of children preferred English so there was little variation in English usage). Finally, ICCs for parent and child generation status, often used as a proxy for acculturation, ranged from .18 to .21. Therefore, sampling diverse communities does seem to have contributed to a more diverse sample than is common in the literature.

Discussion

As researchers continue to study the roles of culture in the behavior, health, and adaptation of minority groups, they must use processes that obtain samples that better represent the diversity within these groups than often has been the case. These efforts are more likely to be successful when researchers use recruitment processes that remover barriers to participation by low-income populations and that are consistent with cultural beliefs and practices of the targeted group. This study demonstrated the value of such processes with data from the first wave of a longitudinal study of Mexican American families. As one result of applying this multiple step method, 750 families participated in the study and the participation rate was high compared to similar studies. Demographic evidence shows that this sample was more diverse on several important dimensions than has been typical of studies of Mexican Americans; the sample was not all English speaking, poor, or from inner city communities. In fact, in contrast to most studies of Mexican Americans, the majority of adults in the current study completed the interview in Spanish. In addition, this study had a high rate of participating fathers making it possible to obtain multiple perspectives on family relationships and functioning. The sample was very similar to the local population in terms of parent education and family income, two important demographic characteristics. However, the sample probably overrepresented recent arrivals and underrepresented Mexican Americans with family histories of three or more generations in the U.S. at least in part because of recruitment criteria (e.g., no bi-ethnic marriages). On the other hand, the census data used for comparison purposes may under represent foreign born and Spanish-speaking Mexican Americans because of their lower participation rates in the census (Citro, Cork, & Norwood, 2004; Van Hook & Bean, 1998). This large sample with families from diverse communities and who represent a wide range of personal and family characteristics, combined with restrictions on family ethnic composition, provides a foundation for careful exploration of cultural issues within the Mexican American population.

Undoubtedly, more can be done to acquire even more diverse samples of Mexican Americans. For instance, despite the importance of personal contact during recruitment, initial contact with potential participants in this study was through written materials, not ideal when some in the population may have low or limited reading ability. When working through schools, legal issues (i.e., restrictions on sharing personal information on students) make it unlikely that first contacts can be in person. Initially, the recruitment process in this study included after school meetings to provide face-to-face interactions with parents before they decided about participating in the study; this was abandoned after very poor turnouts at the first six schools. Research shows that hiring people from each local community to recruit face-to-face within that community can be effective in low-income and minority communities (Dumka et al, 1997). Applying that process might have improved response and participation rates but would have required hiring, training, and supervising recruiters for 42 communities with costs that few projects can afford. In addition, more needs to be done to increase the recruitment and participation of middle class families in research on Mexican Americans. This may require recruitment in urban and suburban communities with very small Mexican American populations again adding considerably to the costs of conducting research.

Conclusions

As research on Mexican Americans continues to grow, there are several lessons learned during this study that may help future studies obtain more diverse and representative samples than has been common. The most important of these are: 1) It is possible to obtain very diverse samples of Mexican Americans, with reasonably high response rates and reasonably high father participation rates. 2) To obtain the most diverse samples, investigators probably need to draw samples from multiple communities that represent the range of residential options. 3) Advisory boards made up of respected members of the community who share an interest in the goals of the research project are inexpensive (e.g., they can be virtually free) and very valuable in helping researchers devise processes that are attractive and in removing institutional or political barriers. 4) Researchers need to make extra efforts to recruit low-income individuals or families (i.e., The recruitment process must educate potential low-income participants about the research process, what it involves, and its possible benefits to overcome fear of the unknown. Develop collaborations with popular and trusted community institutions or leaders to improve credibility. Keep communication as personal as possible. Offer a concrete incentive whenever possible.). 5) Make the research process as consistent with the cultural beliefs and practices of the targeted group as possible (i.e., For Mexican Americans, all research materials must be available in Spanish as well as English and many project personnel must be bilingual and bicultural. Recruiters and interviewers should use formal modes of addressing adults and show respect during all parts of the research process. Using culturally attractive symbols or labels can make a project more attractive on first appearance thus reducing initial resistance. Take a collectivist perspective when explaining the purpose of the research. Be aware and respectful of traditional practices and beliefs [e.g., hierarchical power structures within family].). Hopefully, documentation of lessons learned from studies like this one can contribute to research with more representative samples of Mexican Americans, and other minorities, in the future. Future research on cultural issues in ethnic minority will benefit from additional systematic attempts to develop and implement culturally sensitive and culturally attractive methods of recruitment.

Acknowledgments

Work on this paper was supported, in part, by NIMH Grant MH 68920: Culture, context, and Mexican American mental health. The authors are thankful for the support of Carlos Posadas, Jenn-Yun Tein, our Community Advisory Board, our staff and interviewers, and the families who participated in the study.

References

- Capaldi D, Patterson GR. An approach to the problem to recruitment and retention rates for longitudinal research. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Coronado N, Watson J. Conceptual, methodological, and statistical issues in culturally competent research. In: Hernandez M, Isaacs M, editors. Promoting Cultural Competence in Children's Mental Health Services. Baltimore,MD: Paul H. Brookes; 1998. pp. 305–329. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Ryan KD, Grove K. Children and adolescents of color, where are you? Participation, selection, recruitment, and retention in developmental research. In: McLoyd VC, Steinberg L, editors. Studying minority adolescents: Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical issues. Mahwah, N.J: Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 147–166. [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Sue S. Culturally sensitive research: Where have we gone wrong and what do we need to do now? In: Constantine MG, Sue DW, editors. Strategies for building multicultural competence in mental health and educational settings. New York: Wiley; 2005. pp. 229–246. [Google Scholar]

- Citro CF, Cork DL, Norwood JL. The 2000 census, counting under adversity. National Research Council of the National Academies: Washington, D.C; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dumka L, Garza C, Roosa MW, Stoerzinger H. Recruiting and retaining high risk populations into preventive interventions. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1997;18:25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Lopez VA, Jacobs Carter S. Parenting interventions adapted for Latino families: Progress and prospects. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino Children and Families in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 203–231. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ . New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development Monograph. Family obligation and academic motivation of adolescents from Asian, Latin American, and European American backgrounds. In: Fuligni A, editor. Family obligation and assistance during adolescence: Contextual variations and developmental variations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001. pp. 61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Vega WA, Dimas JM. Acculturative stress and personal adjustment among Hispanic adolescent boys. Journal of Community Psychology. 1994;22:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliss CL, Lee KA, Gutierrez Y, Taylor D, Beyene Y, Neuhaus J, Murrell N. Recruitment and retention of healthy minority women into community-based longitudinal Research. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine. 2001;10:77–85. doi: 10.1089/152460901750067142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Morgan-Lopez A, Saenz D, Sirolli A. Acculturation and the mental health of Latino youths: An integration and critique of the literature. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN, Maramba GG. In search of cultural diversity: Recent literature in cross-cultural and ethnic minority psychology. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7:12–26. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harachi TW, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. Effective recruitment for parenting programs within ethnic minority communities. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 1997;14:23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison AO, Wilson MN, Pine CJ, Buriel R. Family ecologies of ethnic minority children. Child Development. 1990;61:347–362. [Google Scholar]

- LeVine R. Child rearing as cultural adaptation. In: Leiderman PH, Tulkin SR, Rosenfeld A, editors. Culture and infancy: Variations in the human experience. New York: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Vida P, Warda US. Strategies to recruit and retain older Filipino-American immigrants for a cancer screening study. Journal of Community Health. 2005;30:167–179. doi: 10.1007/s10900-004-1956-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens DM. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 1998. Research methods in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with qualitative and quantitative approaches. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2001. Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B. The cultural nature of human development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Jones S, Tein J, Cree W. Prevention science and neighborhood influences on low-income children's development: Theoretical and methodological issues. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:55–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1023070519597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld MJ. Measures of assimilation in the marriage market: Mexican Americans 1970–1990. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Skaff MK, Chesla C, Mycue V, Fisher L. Lessons in cultural competence: adapting research methodology for Latino participants. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:305–323. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Goldberg C, Redmond C. Engaging families in longitudinal prevention intervention research: Discrete-time survival analysis of socioeconomic and socio-emotional risk factors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:157–163. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Orozco C, Suarez-Orozco MM. Children of immigration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Kurtines WM, Fernandez T. Bicultural involvement and adjustment in Hispanic-American youth. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1980;4:353–365. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson TG. Culture, race, and ethnicity: A supplement to Mental Health: A report of the Surgeon General. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. [Retrieved July 8, 2006];Census 2000 Summary File 4 (SF 4) –Sample Data. 2000 from http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DatasetMainPageServlet?_program=DEC&_submenuId=&_lang=en&_ts=

- U.S. Census Bureau. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration; 2001. The Hispanic Population: Census 2000 brief. [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Walker RL, Kwate NOA. Conducting quantitative research in cultural context: Practical applications for research on ethnic minority populations. In: Constantine MG, Sue DW, editors. Strategies for building multicultural competence in mental health and educational settings. New York: Wiley; 2005. pp. 247–268. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hook J, Bean FD. Migration Between Mexico and the United States, Research Reports and Background Materials. Mexico City and Washington DC: Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs and U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform; 1998. Estimating underenumeration among unauthorized Mexican migrants to the United States: Applications of mortality analyses.” In Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs and U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform; pp. 511–550. [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]