Abstract

M2-M3 linkers are receptor subunit domains known to be critical for the normal function of cysteine-loop ligand-gated ion channels. Previous studies of α and β subunits of type “A” GABA receptors suggest that these linkers couple extracellular elements involved in GABA binding to the transmembrane segments that control the opening of the ion channel. To study the importance of the γ subunit M2-M3 linker, we examined the macroscopic and single-channel effects of an engineered γ2(L287A) mutation on GABA activation and propofol modulation. In the macroscopic analysis, we found that the γ2(L287A) mutation decreased GABA potency but increased the ability of propofol to enhance both GABA potency and efficacy compared with wild-type receptors. Indeed, although propofol had significant effects on GABA potency in wild-type receptors, we found that propofol produced no corresponding increase in GABA efficacy. At the single-channel level, mutant receptors showed a loss in the longest of three open-time components compared with wild-type receptors under GABA activation. Furthermore, propofol reduced the duration of one closed-time component, increased the duration of two open-time components, and generated a third open component with a longer lifetime in mutant compared with wild-type receptors. Taken together, we conclude that although the γ subunit is not required for the binding of GABA or propofol, the M2-M3 linker of this subunit plays a critical role in channel gating by GABA and allosteric modulation by propofol. Our results also suggest that in wild-type receptors, propofol exerts its enhancing effects by mechanisms extrinsic to channel gating.

Despite more than 20 years of routine use as an intravenous general anesthetic, the molecular mechanism by which propofol (PRO, 2,6-diisopropyl phenol) produces sedation and unconsciousness remains a mystery. Previous theories proposed that general anesthetics act by nonspecifically disrupting the order of membrane lipids, but it is now widely accepted that PRO exerts its sedative effects through defined amino acids located on the type “A” GABA receptor (GABAAR), an inhibitory ligand-gated ion channel (LGIC) (Franks and Lieb, 1998; Hemmings et al., 2005). Most compellingly, point mutations that render the GABAAR insensitive to enhancement by PRO have been used to produce a genetically engineered mouse strain that is hyper-resistant to PRO anesthesia (Jurd et al., 2003).

In both native and heterologous expression systems, PRO synergistically enhances submaximal GABA responses, leading to a potentiation in GABAergic function (Hales and Lambert, 1991). At saturating GABA concentrations, PRO does not further enhance peak GABAAR responses but rather prolongs the duration of its time course (Manuel and Davies, 1998; Mody and Pearce, 2004). At present, it is still unclear whether PRO achieves these effects by allosterically increasing GABA binding affinity, enhancing GABAAR gating (O'Shea et al., 2000) or by impairing GABAAR desensitization (Bai et al., 1999).

GABAARs are pentameric chloride channels, most commonly composed of two α, two β, and one γ subunit (McKernan and Whiting, 1996). GABA binding occurs at extracellular amino acid residues located at α/β interfaces, whereas PRO binds at amphipathic cavities that are located between the four transmembrane (M1-M4) helices of β subunits (Krasowski et al., 1998; Bali and Akabas, 2004; Richardson et al., 2007). The proposed GABA and PRO binding sites are connected both to the channel gate and to each other via three N-terminal interacting loops known to disrupt channel gating when mutated (Kash et al., 2003, 2004; Newell and Czajkowski, 2003). Specifically, electrostatic interactions between residues in the M2-M3 linker and these N-terminal loops are proposed to couple agonist binding with channel gating at the pore. In support of this idea, GABAARs containing γ2(K289M), a naturally occurring M2-M3 linker mutation found in patients with epilepsy (GEFS+; Baulac et al., 2001), show decreased channel open times in saturating concentrations of GABA (Bianchi et al., 2002; Hales et al., 2006).

In this study, we further characterized the role of this critical M2-M3 linker region in GABA activation and PRO modulation. Specifically, we used a combination of whole-cell and single-channel electrophysiological techniques to compare the gating reaction kinetics of wild-type α1β1γ2 and mutant α1β1γ2(L287A) GABAARs in the presence and absence of PRO. This particular strategy was chosen for the following reasons. First, as a neighbor of γ2(K289M), the γ2(L287A) mutation lies in the critical M2-M3 linker region already known to affect channel gating. Second, a previous alanine scan of the homologous region in the α subunit showed that the corresponding swap at α2(L277A) produced a larger decrease in the GABA EC50 than the α2(K279A) substitution (O'Shea and Harrison, 2000). Third, because the γ subunit is not required for GABA activation (Pritchett et al., 1989), PRO modulation, or PRO direct activation (Jones et al., 1995), introducing the mutation into the single-copy γ2 subunit should specifically perturb GABAAR channel gating without disrupting either GABA or PRO binding. Here, we conclude that the γ2(L287A) mutation introduced a modest defect in GABA-induced gating that simultaneously increased PRO potentiation.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Subunit Expression. For whole-cell recordings, human embryonic kidney 293 cells were grown on poly(lysine)-treated coverslips in 35-mm dishes as described previously (Richardson et al., 2007) and maintained in DMEM+, containing DMEM, l-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 5% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT) at pH 7.4. For single-channel recordings, human embryonic kidney 293 cells were grown directly on dish surfaces with “low-growth” DMEM+ containing 1% fetal bovine serum as described by Lema and Auerbach (2006).

Human α1, β1, and γ2S GABAAR subunit cDNAs in the pCIS expression vector were generously provided by Neil Harrison (Weill Medical College of Cornell University, Ithaca, NY). The γ2S(L287A) mutation was introduced using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and confirmed by complete dideoxy-sequencing of the insert. Cells were transfected with α1, β1, and γ2S or γ2S(L287A) GABAAR subunit cDNAs in a 1:1:1 ratio using the calcium phosphate method. For whole-cell recordings, green fluorescent protein cDNA was added to the transfection mixture to identify positively transfected cells. For single-channel recordings, human CD8 surface antigen was used as the marker, and then cells were treated with anti-CD8 antibody-coated Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Whole-Cell Electrophysiology. For GABA dose-response curves, GABAAR currents were recorded using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique as described previously (Richardson et al., 2007). In brief, cells were voltage-clamped at -60 mV, whereas drugs (GABA and/or PRO) were applied via the extracellular solution using a rapid solution changer. Even though we waited sufficient time for receptors to fully recover between GABA applications, we cannot exclude the effects of fast desensitization before the peak response was reached. Extracellular solution contained 145 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 6 mM d-glucose, and 10 mM HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.4 using KOH. Pipettes were filled with intracellular solution containing 145 mM N-methyl-d-glucamine, 5 mM K2ATP, 1.1 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, and 0.1 mM CaCl2, adjusted to pH 7.2 using KOH.

Single-Channel Electrophysiology. We recorded single-channel activity using the cell-attached patch configuration as described in Lema and Auerbach (2006). In brief, data were recorded using a +80 mV pipette potential (∼-100 mV estimated cell membrane potential) and analyzed using QuB software (http://www.qub.buffalo.edu). In this configuration, drugs were equilibrated with GABAARs via the recording pipette for the duration of the experiment. The bath solution contained 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. Pipettes were filled with solution containing 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4.

Whole-Cell Analysis. Dose-response curve data were fitted using the following form of the Hill equation with four free parameters: ((Imax - Imin)·(DnH/(DnH + EC50nH)) + Imin, where Imax is the maximal normalized response in saturating GABA, Imin is the normalized response in the absence of GABA, D is the GABA concentration, nH is the Hill coefficient, and EC50 is the concentration of GABA producing a half-maximal response. All reported values are taken from these parameters, fitted from individual experiments that were then pooled within each condition.

Overview of Single-Channel Analysis. As described in Lema and Auerbach (2006), we analyzed data files using SKM idealization (Qin, 2004) and MIL fitting (Qin et al., 1996) of kinetic parameters. Note that using these algorithms makes “oversampling” (e.g., sampling faster than the Nyquist theorem) unnecessary, compared with threshold-based event detection. Therefore, recordings were low-pass-filtered at 10 kHz using a four-pole Bessel filter and digitized at 20 kHz using QuB analysis software. Data were fitted using a 0.15-ms “dead time,” a value that was approximately two times faster than the shortest measured time constant.

Definition of a “Burst.” By adapting the method described in Lema and Auerbach (2006), we simplified the interpretation of our single-channel burst analysis by applying a number of conditions and criteria to our definition of a burst. First, to minimize contributions from monoliganded and unliganded closed states to our measurements of gating parameters, we used a saturating concentration of GABA. Second, we applied a variable tcrit to each patch that removed all but the two shortest closed time components from our analysis. This decision was guided by previous determinations that only the two shortest closed-time components are GABA concentration-independent and that burst open probabilities (burst Po values) approach their maximum at tcrit values <20 ms (Newland et al., 1991). Our own experiments using 100 μM GABA were in general agreement with these findings, because burst Po values at 100 μM GABA and 5 mM GABA converged at tcrit values <20 ms (data not shown). Using this procedure, we effectively removed long-lived desensitized closed states from our estimates of gating (Newland et al., 1991; Lema and Auerbach, 2006) and reduced our window of analysis from clusters (defined using a fixed tcrit of 100 ms per patch) to bursts (defined using a variable tcrit of <20 ms per patch). Third, we applied a 30-event minimum criterion to our definition of a burst. This criterion allowed us to measure enough intraburst events to extract meaningful kinetic data of the gating reaction (e.g., to observe transitions between multiple open states) yet still exclude thousands of short-lived, single-opening bursts. By applying these three conditions to our analysis, we were then able to extract meaningful estimates of GABAAR intraburst gating parameters using models directly fitted from intraburst open and closed dwell times.

Analysis of a Burst. Supplemental Figure S1 shows a representative analysis of a burst from wild-type α1β1γ2 GABAARs equilibrated with 5 mM GABA. We used the QuB AMP function to sort 111 individual events into two conductance classes (closed and open), shown in Supplemental Figure S1A as two Gaussian distributions. Under our experimental conditions, wild-type GABAARs predominantly open with ∼2 pA amplitudes. Using this method, low-amplitude classes (e.g., subconductance states) were not separately quantified. Supplemental Figure S1B shows the dwell times for each closure within the burst, whereas Supplemental Figure S1C shows the corresponding open dwell times. Mean values for the closed and open times in this burst were calculated as 1.29 and 1.33 ms, respectively. By using the following approximation to calculate the mean burst Po, (open time/(open time + closed time)), we calculated a value of 0.51 (1.33/(1.29 + 1.33)) for this individual burst. This analysis was then repeated for all the bursts in this patch, as well as all the patches recorded under the four test conditions (wild-type and mutant GABAARs with or without PRO).

Evaluation of Curve-Fitting by Log Likelihood. Our decision to use two closed components and up to three open components to fit and model our data are guided by attempts to maximize the log-likelihood of the fit while using the least number of closed and open time components to adequately describe the data. Previous GABAAR single-channel studies have observed four closed (C) and two open (O) intraburst components (Mortensen and Smart, 2007), 3C and 3O components (Lema and Auerbach, 2006), 5C and 3O components (Macdonald et al., 1989), and 3C and 3O components (Steinbach and Akk, 2001) when fitting single patches. By using a change in log-likelihood cutoff of -10 (Lema and Auerbach, 2006), our aim was to avoid overparameterization of our data yet still allow the measurement of rare, long-lived openings. This cutoff is conservative versus other methods that attempt to discriminate between simple and more complex models (Csanády, 2006). In addition to a log-likelihood evaluation of curve-fitting, we also performed a manual “reality check” for the fit of each experiment. Fits of the data based on chosen kinetic models were visually inspected for goodness of fit, and fits generating rate constants with near-zero or near-infinite values were rerun with different starting values, or discarded (in the case of unnecessary components), as appropriate.

Alternate Kinetic Models. Using QuB software, we calculated that two closed (C) and three open (O) states can be connected in 98 nonequivalent topologies (15 without loops). Like previous investigators (Weiss and Magleby, 1989; Jones and Westbrook, 1995; Haas and Macdonald, 1999; Steinbach and Akk, 2001; Lema and Auerbach, 2006), we were unable to distinguish a single “best” model using stationary (equilibrium) kinetic measurements. Therefore, rather than test all possible models using a “brute force” approach on the WT - PRO condition, or simulate macroscopic responses to saturating GABA pulses, we based our kinetic scheme on a recent model that was developed using both of these strategies (Lema and Auerbach, 2006). Compared with Lema and Auerbach's six-state “core” (3C, 3O) model, our five-state (2C, 3O) model topology was identical except for the omission of a “C3” closed state. Because the corresponding long-lived third closed component may contain GABA concentration-dependent closures (Newland et al., 1991), and tcrit values <20 ms removed this third closed component, we chose to omit this closed state from our final kinetic models of intraburst gating. Note that including this C3 state in our model slightly increased the observed mean burst closed times and decreased the corresponding observed mean burst Po values, but did not change the relative trends that we observed and report here in Tables 1, 2, 3.

TABLE 1.

Mean single-channel parameters for wild-type α1β1γ2s and mutant α1β1γ2s(L287A) receptors

PRO increased the mean single-channel burst open time and mean burst Po only in mutant receptors. In the absence of PRO, mutant receptors had a higher mean burst closed time and lower mean burst Po than wild-type receptors. In the presence of PRO, mutant receptors had the highest mean burst open time and mean burst Po of the four conditions. The total numbers of patches for each condition were as follows: WT − PRO, 7; WT + PRO, 6; MUT − PRO, 7; MUT + PRO, 8.

|

Mean Channel Amplitude

|

Mean Burst

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed Time | Open Time | Po | ||

| pA | ms | ms | ||

| WT − PRO | 1.75 ± 0.05 | 1.71 ± 0.19 | 2.35 ± 0.31 | 0.54 ± 0.03 |

| WT + PRO | 1.70 ± 0.06 | 1.32 ± 0.16 | 2.26 ± 0.31 | 0.59 ± 0.05 |

| MUT − PRO | 1.74 ± 0.07 | 1.43 ± 0.20 | 1.26 ± 0.08* | 0.47 ± 0.04 |

| MUT + PRO | 1.96 ± 0.14 | 0.77 ± 0.14† | 7.32 ± 2.07† | 0.79 ± 0.07† |

P < 0.05 vs. WT − PRO.

P < 0.05 vs. MUT − PRO.

TABLE 2.

Time constants for wild-type α1β1γ2s and mutant α1β1γ2s(L287A) receptors

PRO lengthened all three single-channel open-time components in mutant receptors but not in wild-type receptors. Open-time constants are reported as unweighted mean values ± S.E.M. pooled from individual fits of each patch. Values from global fits of pooled data are shown in parentheses and are automatically weighted by the number of events detected for each component. When a component in the individual fit was missing compared with the global fit, the value was ignored and designated N.D. when calculating the mean values. PRO produced significant increases in the open time constants of mutant receptors. To a lesser extent, PRO also decreased the longer of the two closed time components (τC2) in mutant receptors. Under our single-channel recording and analysis conditions, PRO had no effect on wild-type receptors.

|

Time Constants

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τC1 | τC2 | τO1 | τO2 | τO3 | |

| ms | |||||

| WT − PRO | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 1.74 ± 0.14 | 0.72 ± 0.06 | 1.95 ± 0.22 | 8.61 ± 1.71 |

| (0.46) | (2.02) | (0.78) | (2.48) | (9.02) | |

| WT + PRO | 0.47 ± 0.08 | 1.73 ± 0.14 | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 1.91 ± 0.14 | 6.10 ± 0.54 |

| (0.41) | (1.81) | (0.69) | (2.18) | (7.12) | |

| MUT − PRO | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 1.91 ± 0.24 | 0.69 ± 0.07 | 2.01 ± 0.14 | N.D. |

| (0.56) | (2.50) | (0.84) | (2.11) | ||

| MUT + PRO | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 1.19 ± 0.20† | 1.14 ± 0.15† | 5.71 ± 0.80† | 24.97 ± 2.63† |

| (0.30) | (1.27) | (0.78) | (4.94) | (25.44) | |

N.D., not determined.

* P < 0.05 vs. WT − PRO.

P < 0.05 vs. MUT − PRO.

TABLE 3.

Fractional areas for wild-type α1β1γ2s and mutant α1β1γ2s(L287A) receptors

Fractional areas are reported as unweighted mean values ± S.E.M., pooled from individual fits of each patch. Values from global fits of pooled data are shown in parentheses and are automatically weighted by the number of events detected for each component. When a component in the individual fit was missing compared to the global fit, the value was ignored and treated as 0 when calculating the mean values. PRO produced an increase in the fractional area of the longest open-time component (AO3) of mutant receptors. Under our single-channel recording and analysis conditions, PRO had no effect on wild-type receptors.

|

Fractional Areas

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC1 | AC2 | AO1 | AO2 | AO3 | |

| ms | |||||

| WT − PRO | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.68 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.06 |

| (0.36) | (0.64) | (0.54) | (0.54) | (0.13) | |

| WT + PRO | 0.37 ± 0.07 | 0.63 ± 0.07 | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 0.68 ± 0.04 | 0.15 ± 0.05 |

| (0.38) | (0.62) | (0.27) | (0.61) | (0.12) | |

| MUT − PRO | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.69 ± 0.02 | 0.53 ± 0.08* | 0.47 ± 0.08 | 0.00* |

| (0.34) | (0.66) | (0.71) | (0.29) | ||

| MUT + PRO | 0.38 ± 0.05† | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.32 ± 0.09 | 0.34 ± 0.07† | 0.34 ± 0.13† |

| (0.57) | (0.43) | (0.17) | (0.27) | (0.56) | |

P < 0.05 vs. WT − PRO.

P < 0.05 vs. MUT − PRO.

Statistical Analysis. Comparison of global single-channel parameters were performed by directly comparing log-likelihood values, whereas parameters from individual fits were compared at the p < 0.05 significance level with a Student's unpaired t test. Dose-response curve parameters (with or without PRO) were taken from responses from the same cell, so results were compared using a Student's paired t test at the p < 0.05 significance level.

Materials. Unless otherwise stated, all reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Results

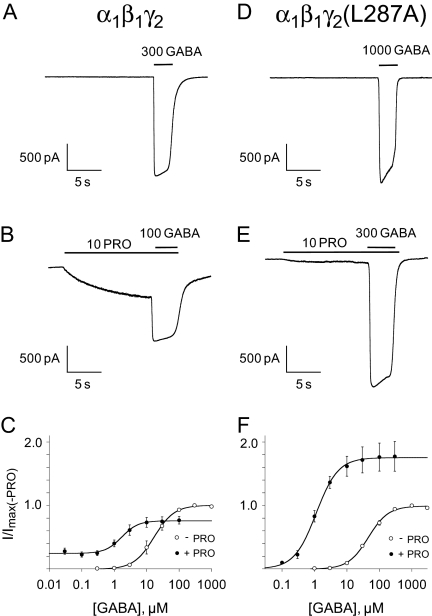

PRO Did Not Increase Wild-Type Maximal Responses. Before examining the effects of an M2-M3 linker mutation on the single-channel kinetics of GABAARs, we began by comparing GABA whole-cell dose-response curves under four test conditions: wild-type α1β1γ2 GABAARs in the absence of PRO (WT - PRO); wild-type receptors in the presence of PRO (WT + PRO); mutant α1β1γ2(L287A) receptors in the absence of PRO (MUT - PRO); and mutant receptors in the presence of PRO (MUT + PRO). In our analysis, we placed a special emphasis on comparing maximal responses at agonist saturation (Imax) in each of the four conditions. Although such measurements are undoubtedly obscured by rapid desensitization during the agonist application (Colquhoun, 1998; Wagner et al., 2004), we used the Imax (+PRO)/Imax (-PRO) ratio at agonist saturation (ε, relative efficacy) to obtain a rough estimate of the effect of PRO on channel gating (O'Shea and Harrison, 2000; O'Shea et al., 2000). Each cell was tested with and without PRO, and peak responses at each GABA concentration were normalized versus the Imax(-PRO) for each cell.

Figure 1A shows a wild-type response to a 2-s application of 300 μM GABA. For the WT - PRO condition, peak responses were typically maximal at ≥300 μM GABA. Figure 1B shows the same cell's response to 100 μM GABA + 10 μM PRO after an 8-s preapplication of 10 μM PRO. Before the application of GABA, 10 μM PRO directly activated wild-type receptors, producing responses that were ∼20% of Imax(-PRO). For the WT + PRO condition, application of 100 μM GABA produced maximal peak responses, but Imax(+PRO) was smaller than Imax(-PRO) by ∼ 20%. This decrease in Imax was probably due to a desensitization of wild-type receptors by PRO before GABA application, because an 8-s preapplication of EC20 GABA produced the same effect (data not shown). The effects of PRO on pooled GABA dose-response curves are summarized in Fig. 1C and the figure legend, with values pooled from individually fitted experiments. Compared with the WT - PRO condition, the WT + PRO condition showed a ∼7-fold decrease in the GABA EC50 and a 22% decrease in GABA ε. Taken together, these experiments yielded two primary findings: first, GABA concentrations ≥300 μM were sufficient to saturate wild-type receptors in both the presence and absence of PRO; and second, 10 μM PRO preferentially enhanced submaximal GABA responses at wild-type receptors.

Fig. 1.

The γ2(L287A) mutation reduces sensitivity to GABA but increases receptor efficacy in the presence of propofol. A and B, whole-cell current traces induced by GABA in the absence and presence of 10 μM PRO. The durations of GABA and PRO application are indicated by the bars above the current traces. C, comparison of the GABA concentration-response relationship in the absence and presence of 10 μM PRO. In wild-type receptors, the GABA EC50 decreased from 18.9 ± 6.2 to 2.7 ± 1.4 μM, and the relative efficacy decreased from 0.99 ± 0.02 to 0.77 ± 0.08 in the presence of propofol. PRO had no significant effect on the Hill coefficient (from 1.83 ± 0.05 to 2.03 ± 0.23) versus the WT - PRO condition. D to F, same as A, B, and C but for mutant α1β1γ2(L287A) GABAA receptors. In mutant receptors, the GABA EC50 decreased from 47.9 ± 5.9 to 1.2 ± 0.4 μM, and the relative efficacy increased from 1.00 ± 0.01 to 1.76 ± 0.22 in the presence of PRO. PRO had no significant effect on the Hill coefficient (from 1.44 ± 0.11 to 1.62 ± 0.29) versus the MUT - PRO condition. Significance was assessed at the p < 0.05 level. 4 ≤ n ≤5.

PRO Increased Mutant Maximal Responses. Next, we tested the whole-cell responses of mutant α1β1γ2(L287A) GABAARs to increasing concentrations of GABA. Figure 1D shows a response to 1000 μM GABA, a concentration that typically saturated receptor responses in the MUT - PRO condition. Compared with the WT - PRO condition, receptors in the MUT - PRO condition showed a ∼2.5-fold higher GABA EC50 value and a slightly reduced Hill slope (Fig. 1D), indicating that this mutation produced a slight loss of receptor function. We then tested whether PRO could restore wild-type GABA sensitivity to mutant receptors. Figure 1E shows a representative response to 300 μM GABA + 10 μM PRO, which was saturating in the MUT + PRO condition. In contrast to our results with wild-type receptors, 10 μM PRO produced only minimal direct activation [responses were 2% of Imax(-PRO)]. After coapplication with a saturating concentration of GABA, the Imax(+PRO) was larger than Imax(-PRO), indicating that PRO enabled supramaximal GABA responses in mutant receptors. Figure 1F and the figure legend summarize these results: the MUT + PRO condition produced a 40-fold decrease in GABA EC50 and a 76% increase in GABA ε versus the MUT - PRO condition. We also noted that 10 μM PRO did not restore wild-type GABA sensitivity to mutant receptors but rather overshot the GABA EC50 value in the WT + PRO condition by ∼2-fold.

In summary, these experiments yielded three major findings. First, we established that concentrations of ≥1 mM GABA were saturating at mutant receptors in both the presence and absence of PRO. Second, 10 μM PRO potentiated all concentrations of GABA at mutant receptors, leading to an increase in GABA ε and a decrease in the GABA EC50. Third, we hypothesize that mutant receptors have an enhanced susceptibility to potentiation by PRO, as evidenced by the larger increase in GABA ε and larger GABA EC50 shift versus wild-type receptors. This susceptibility is probably not due to improved PRO binding, because the EC50 values for PRO direct activation at mutant receptors (30.7 ± 4.1 μM, n = 11) was higher than at wild-type receptors (20.3 ± 3.1 μM, n = 9). Rather, mutant receptors showed a higher Hill coefficient for PRO direct activation (4.45 ± 0.48, n = 11) than wild-type receptors (1.34 ± 0.13, n = 9), suggesting an altered effect of PRO on receptor gating. To directly test this hypothesis, we analyzed the single-channel responses of receptors in each of the four test conditions.

PRO Did Not Affect Wild-Type Intraburst Gating. In our whole-cell experiments, we assume that applications of ≥1 mM GABA produce full receptor occupancy in each of the four conditions. Therefore, we recorded the single-channel behavior of wild-type α1β1γ2 receptors equilibrated with 5 mM GABA. At agonist saturation, standard receptor activation models (Del Castillo and Katz, 1957) define receptor gating as a continuous and uniform “chatter” (short-lived openings and closures) of receptor activity as the channel oscillates between liganded closed and open states. In the patch shown in Fig. 2A, we observed channel openings in the WT - PRO condition as brief, ∼2 pA upward deflections. Although GABA was present during the entire recording, these openings were not continuous but were separated by both short- and long-duration closures.

Fig. 2.

Propofol has no measurable effect on the intraburst kinetics of α1β1γ2 GABAA receptor single-channel events. A, single-channel openings recorded from a cell-attached patch. The GABA concentration in the electrode was 5 mM. B and C, expanded time-scale views of a cluster (B) and a burst (C). The open-closed idealizations of burst activity are shown above the current trace. D to F, same as A, B, and C but for receptors in the presence of 5 mM GABA and 10 μM PRO.

The long-duration pauses in channel activity are generally defined as desensitization, a receptor state in which agonist binding sites are occupied, but the channel is closed (Newland et al., 1991; Mortensen and Smart, 2007). For this patch, we estimate that wild-type channels were inactive (cumulatively) for more than 75% of the 20-min recording. These long-lived closures tended to cluster channel activity, shown at a faster time-scale in Fig. 2B. Note that although these clusters were readily apparent in 5 mM GABA, we did not attach any special significance to the duration of these clusters. Therefore, we uniformly applied tcrit values of 100 ms to each patch to generate segment lists of variable-length clusters, which were then broken down into bursts using variable tcrit values <20 ms for final analysis (see Materials and Methods).

We also observed that recordings routinely contained activity from multiple channels, shown here by the occasional simultaneous “stacked” openings. To minimize the effects of these simultaneous openings on our measurements, we excluded data segments in which more than 2% of the openings were stacked. The presence of multiple channels in the patch also precluded us from rigorously determining the degree of channel desensitization. Despite this complexity, because desensitized closures are generally considered to be longer than the closures associated with gating, we safely used a tcrit procedure to remove them from our analysis without affecting our estimates of gating (Lema and Auerbach, 2006). Typically, we found that patches contained at least five closed components with durations >20 ms (data not shown), but they were not analyzed further in this study.

Figure 2C shows a representative burst displayed at a fast time-scale after the application of tcrit. In the absence of contamination from unliganded and monoliganded closures (by using saturating agonist concentrations), long-lived desensitized closures (by using tcrit), and double openings (by manual deletion from the record), we calculated an unambiguous measurement of “intraburst” gating kinetics from the durations of the remaining open and closed dwell times. Table 1 shows the mean channel amplitude, mean burst closed and open times, and mean burst Po (open probability within a burst) calculated for multiple bursts pooled from multiple patches. Despite the removal of long-lived (e.g., >20 ms) closures, the pooled mean burst Po for channels in the WT - PRO condition was actually quite low (0.53 ± 0.03).

Figure 2, D to F, show the behavior of wild-type channels in 5 mM GABA + 10 μM PRO. Compared with channels in the WT - PRO condition (Fig. 2, A-C), PRO produced no consistent differences in channel activity at agonist saturation shown at either the cluster (Fig. 2E) or burst (Fig. 2F) level of analysis. Compared with channels in the WT - PRO condition, Table 1 shows that PRO produced no significant effects in the mean channel amplitude, mean burst closed and open times, or mean burst Po when pooled from multiple bursts and patches. PRO also produced no significant changes in closed times between clusters when analyzed at low resolution (threshold-based detection at 0.2 kHz digital filtering; data not shown), although the presence of multiple channels in the WT + PRO condition made our desensitization measurements subject to the same caveats described previously for the WT - PRO condition.

PRO Increased Mutant Intraburst Gating. Because of confounding factors in our whole-cell experiments such as desensitization and varying numbers of receptors expressed per cell, we were unable to conclude from normalized GABA ε values (Fig. 1, legend) or from un-normalized Imax amplitudes (data not shown) if the γ2(L287A) mutation impaired receptor gating. To resolve this issue, we next recorded the single-channel behavior of mutant α1β1γ2(L287A) receptors equilibrated with 5 mM GABA.

As shown in Fig. 3, A to C, and Table 1, the ∼2 pA openings indicate that mutant receptors open with normal single-channel conductances and also confirm that the mutant γ2(L287A) subunits incorporate correctly with the wild-type α1 and β1 subunit background (Angelotti and Macdonald, 1993). Although not immediately obvious from visually comparing the wild-type receptor burst in Fig. 2C with the mutant receptor burst in Fig. 3C, Table 1 reveals that on average, bursts in the MUT - PRO condition showed a slightly lower mean burst open time than channels in the WT - PRO condition. Therefore, these results confirmed our hypothesis that the M2-M3 linker mutation produces a moderate GABA gating defect.

Fig. 3.

Propofol increases the intraburst Po of α1β1γ2(L287A) GABAA receptor single-channel events. A, single-channel openings recorded from a cell-attached patch. The GABA concentration in the electrode was 5 mM. B and C, expanded time-scale views of clusters (B) and open-closed idealization (C) of burst activity. D, E, and F, same as A, B, and C but for receptors in the presence of 5 mM GABA and 10 μM propofol.

Because our macroscopic results suggest that PRO increased the GABA ε value in mutant receptors, we also tested whether PRO could also increase the burst Po at the single-channel level. Figure 3, D to F, shows that 10 μM PRO produced remarkable effects on mutant channel behavior in the continued presence of 5 mM GABA. At both cluster (Fig. 3E) and burst (Fig. 3F) time scales, channels in the MUT + PRO condition obviously spent a much higher proportion of time in the open state than channels in the MUT - PRO condition. In data pooled from multiple bursts and multiple patches (Table 1), the MUT + PRO condition showed an increased mean burst open time and mean burst Po, a decreased mean burst closed time, and an unchanged mean channel amplitude compared with the MUT - PRO condition. We also noticed that, in agreement with our whole-cell comparisons of relative efficacy (GABA ε, Fig. 1 legend), the mean burst Po (Table 1) of the MUT + PRO condition was higher than in the WT + PRO condition, suggesting that mutant receptors have a higher “ceiling” for potentiation than wild-type receptors. Because the mean burst Po of receptors in the WT - PRO condition was low enough (0.54 ± 0.05) to accommodate potentiation, we were intrigued as to why wild-type receptors did not show a similar increase in mean burst Po. As a result, we continued our investigation into the mechanistic aspects of GABAAR gating kinetics.

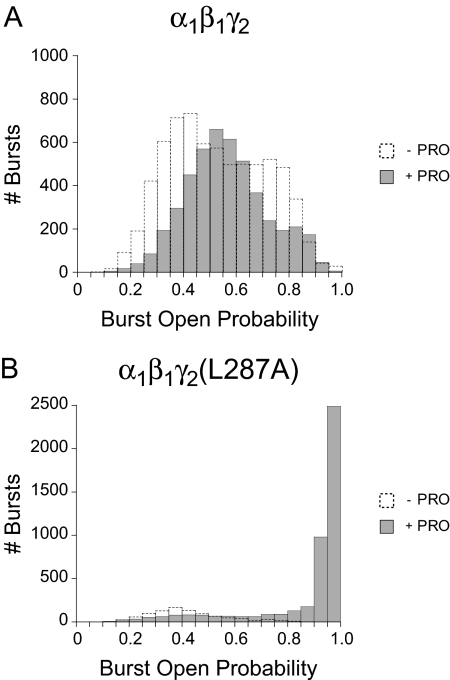

PRO Enabled “High Po” Gating in Mutants. As reported in other GABAAR investigations using various preparations and subunit combinations (Newland et al., 1991; Keramidas et al., 2006; Lema and Auerbach, 2006), we observed that some patches in the WT - PRO condition showed clear “modes” of channel activity. In our experiments, three of eight patches in the WT - PRO condition had channel-bursting behavior that was easily separable into multiple modes, but the appearance and transitions between those modes seemed to be random.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of burst Po values pooled from multiple bursts and multiple patches within each of the four conditions. After plotting the number of bursts observed in 0.05 Po width bins, the histogram revealed that channels in the WT - PRO condition showed major modes of activity centered at 0.40 to 0.45 and 0.70 to 0.75 Po (Fig. 4A). In comparison, channels in the WT + PRO condition showed a major mode centered at 0.50 to 0.55 and a minor one centered at 0.80 to 0.85 Po. In the MUT - PRO condition, we observed a single mode centered at 0.35 to 0.40 Po (Fig. 5B), whereas channels in the MUT + PRO condition showed a minor mode centered at 0.40 to 0.45 and a major one centered at 0.95 to 1.00.

Fig. 4.

Propofol increases the number of high-Po bursts in α1β1γ2(L287A) GABAA receptors but not in wild-type receptors. Binned data from multiple experiments were pooled in wild-type α1β1γ2 (A) and mutant α1β1γ2(L287A) GABAA receptors (B) in the absence and presence of 10 μM propofol. The normalized percentage of bursts showing burst Po values ≥ 0.70 was the following: WT - PRO, 29%; WT + PRO, 26%; MUT - PRO, 8%; MUT + PRO, 87%.

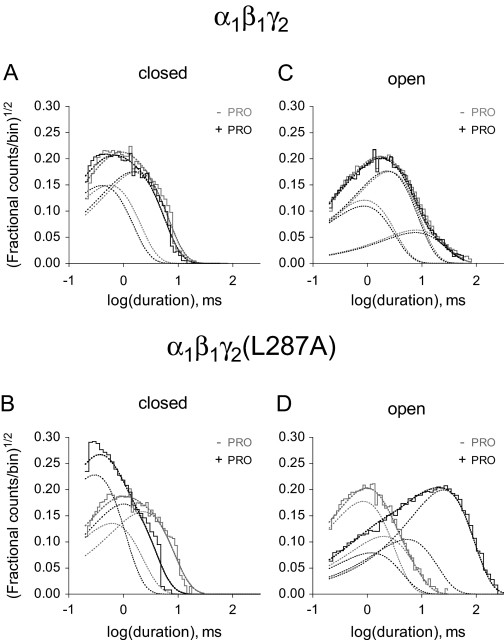

Fig. 5.

Propofol had no measurable effect on the closed- and open-time components in wild-type receptors. In mutant receptors, propofol reduced the duration of one closed-time component, increased the duration of two open components, and introduced a third long-lived component. Histograms represent binned data from representative patches containing wild-type (A and C) or mutant receptors (B and D). Dotted lines show the individual and summated components obtained by fitting the kinetic schemes shown in Fig. 6A.

Because the number of modes and the underlying cause of this modal activity in GABAARs was unknown, we arbitrarily categorized bursts into “high-Po” and “low-Po” gating modes using a Po value of 0.70. To a first approximation, PRO increased the normalized percentage of high-Po bursts in mutant (MUT - PRO, 8%; MUT + PRO, 87%) but not wild-type receptors (WT - PRO, 29%; WT + PRO, 26%). Furthermore, it seems that PRO enabled a 0.95 to 1.00 Po gating mode in the MUT + PRO condition that was never observed in the MUT - PRO condition and only rarely observed in the WT - PRO and WT + PRO conditions.

PRO Increased Mutant Intraburst Open Times. We also tested whether PRO had subtle effects on the relative distributions of subpopulations of channel dwell times (e.g., specific kinetic components) that were not reflected in the channel mean open and closed times. As shown in closed time histograms and curve fits (solid lines) including components (dotted lines), two closed components were required to adequately fit data from a patch in the WT - PRO condition (Fig. 5A, gray lines) and a patch in the WT + PRO condition (Fig. 5A, black lines). For this patch, the two closed components had 0.5- and 1.7-ms durations in the absence of PRO, the 1.7-ms component had the larger area, and both components were unchanged by the addition of PRO. In Fig. 5C, three open components were required to adequately fit the open time histograms of a patch in the WT - PRO condition. The open components had durations of 0.8, 2.4, and 7.3 ms, and the 2.4-ms component had the largest area. As with the closed components, the addition PRO did not change these open components in wild-type receptors.

In contrast, PRO had multiple effects on the open- and closed-time components of mutant receptors. Figure 5B shows that two closed components were required to fit data from patches in the MUT - PRO and MUT + PRO conditions. In the absence of PRO, the two closed components had 0.6- and 2.2-ms durations, the 2.2-ms component having the largest area, but in the presence of PRO, the second component was shortened to 0.9 ms, and the areas of the two components were roughly equal. In Fig. 5D, only two open components were required to fit the MUT - PRO patch, but three components were necessary to fit the MUT + PRO patch. In the absence of PRO, the open components had 0.8- and 1.9-ms durations, whereas the 0.8-ms component had the largest area. In the presence of PRO, the open components had 1.1-, 5.0-, and 23.4-ms durations, and the 23.4-ms component had the largest area.

As summarized in Tables 2 and 3, the primary effect of PRO on data pooled from multiple patches containing mutant receptors was to lengthen the durations of two existing open components, to reintroduce a third open component, and to increase the area of a 25-ms time component. To a lesser extent, PRO also shortened the duration of a 1.9-ms closed time component to 1.2 ms in mutant receptors. Taken together, these findings provide a detailed description of how PRO potentiates mutant receptor gating, and further support our conclusion that “intraburst” wild-type receptor gating is unaffected by PRO.

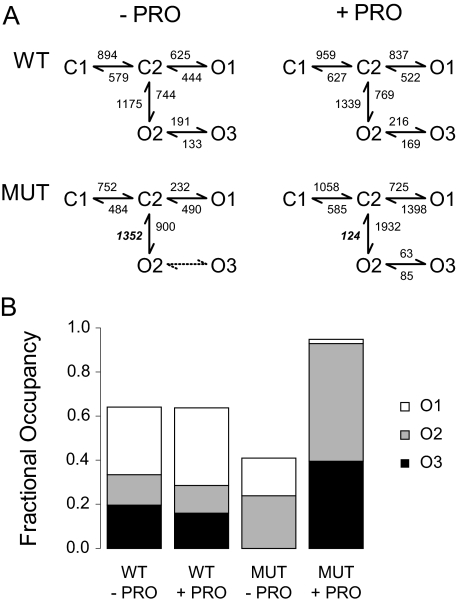

Modeling and Simulation Reveal Two GABAAR Activation Pathways. As detailed under Materials and Methods, we used QuB software to generate kinetic schemes (Fig. 6A) and simulations of single-channel activation during our global fitting of data pooled within each of the four conditions. We based our model topology on previously published schemes for wild-type α1β1γ2 GABAARs (Lema and Auerbach, 2006) with the omission of a third long-lived closed state that was deemed unnecessary by comparison of log-likelihood values and visual inspection of our fits. These models assume equilibration with saturating concentrations of GABA and therefore do not include desensitized or subliganded closed states.

Fig. 6.

PRO increased the fractional occupancy of long-lived open states in mutant but not wild-type receptors. A, kinetic schemes and rate constants (s-1) for the activation and modulation of wild-type α1β1γ2 and mutant α1β1γ2(L287A) GABAA receptors. The schemes shown were used to idealize and fit data from each patch. The rate constants represent the global parameters from the fitting of pooled data. In the MUT - PRO condition, only two open states were required to adequately fit the data. B, comparison of the relative contribution of the three open states O1, O2, and O3 to channel activation obtained from intraburst dwell times. For the simulation of whole-cell dose response curves (see text), two sequential GABA binding steps were attached to C1. In wild-type receptors, PRO had no effects on the simulated GABA EC50 (from 52.2 to 52.8 μM in the absence and presence of PRO, respectively), relative efficacy (from 1.00 to 0.99), or Hill slope (from 1.46 to 1.46) versus the WT - PRO condition. In mutant receptors, PRO reduced the GABA EC50 (from 73.8 to 16.2 μM), increased the relative efficacy (from 1.00 to 2.29), and slightly increased the Hill slope (from 1.46 to 1.71) versus the MUT - PRO condition.

It is noteworthy that our five-state model for wild-type GABAAR gating suggests two alternate GABA activation pathways. The top branch (C1-C2-O1) proceeds directly toward an opening after transition through two agonist-bound closed states, whereas the bottom branch (C1-C2-O2-O3) proceeds to two interconnected open states. One might intuitively expect that the lower branch (with more open states) would produce a higher burst Po. However, when we simulated the two pathways separately, we found that the higher pathway produced a “burst” Po of 0.46, whereas the lower pathway produced a “burst” Po of 0.48. When both pathways were simulated together, the simulated “burst” Po increased to 0.64, as receptors freely hopped between the upper and lower pathways before eventually dwelling in long-lived closures. Because of the innate connectivity between these two pathways and the similarity of the time constants between them, we could not detect clear transitions between different modes of gating, as has been reported with other LGICs (Newland et al., 1991; Popescu and Auerbach, 2003; Lema and Auerbach, 2006).

To better understand the role the γ2(L287A) mutation plays in GABA-induced gating, we compared the models and rate constants generated for the WT - PRO and MUT - PRO conditions. With the exception of the O3 state, the two conditions were well fit using identical state topologies. Because the addition of the O3 state in the MUT - PRO condition produced either near-zero or near-infinite rate constants, we assumed that this state was undetectable to our analysis. This missing O3 state causes receptors that activate by the lower activation pathway to prematurely close versus receptors in the WT - PRO condition, which occasionally make O2 to O3 transitions before closing. Of the remaining rate constants, the mutation had the largest effect on the C2 to O1 rate constant (from 625 to 232/s). In the upper activation pathway, this 2.7-fold decrease contributes to the modest decrease in mean burst open time that we observed in our single-channel experiments.

Next, we compared the effects of PRO in wild-type and mutant receptors. Consistent with its lack of effect on any of the intraburst closed or open time components, the WT + PRO condition produced only modest (<1.4-fold) changes in the individual rate constants compared with the WT - PRO condition. In contrast, the MUT + PRO condition showed a 10.9-fold decrease in the O2 to C2 transition (from 1352 to 124/s) and the reappearance of the O3 open state. By blocking this “escape route” for receptors that favor the lower activation pathway, PRO effectively traps receptors in O2 and O3, leading to longer mean open times and higher burst Po values in single-channel experiments and higher GABA ε values in whole-cell experiments. Indeed, after correcting for the differing overall open occupancies, our simulations suggest that although receptors in the WT + PRO condition show a 1.2-fold preference for the upper pathway, receptors in the MUT + PRO condition show a >50-fold preference for the lower pathway.

To present a more intuitive description of the effect of the mutation on receptor activation and modulation, we constructed a stacked histogram that represents the simulated fractional occupancies for the open states calculated from these models and rate constants (Fig. 6B). We should emphasize that because of the branched topologies of the kinetic schemes, calculation of the relationships between the simulated fractional occupancies of each open state and the fitted fractional areas of each open component can be complex. Notwithstanding these complexities, comparing the WT - PRO with the MUT - PRO condition revealed that the mutation increased the fractional occupancy of the O2 state at the expense of the O1 and O3 states, with no occupancy of the O3 state. In comparing the summed fractional occupancies, we also observed that the mutant produced a 1.6-fold reduction in the overall open occupancy versus wild-type receptors.

Although PRO had negligible effects on the fractional and overall open-state occupancies of wild-type receptors, PRO produced large changes in the open-state occupancies of receptors in the MUT + PRO compared with the MUT - PRO condition. Specifically, receptors in the MUT + PRO condition showed a reduced fractional occupancy of the O1 state, increased fractional occupancies of the O2 and O3 states, and an increased overall open occupancy compared with the MUT - PRO condition. Given that the mean burst Po values in Table 1 represent unweighted mean values pooled from multiple experiments, our simulated values for overall open occupancies are in relatively good agreement with the trends we observed in our experimental data.

Finally, to relate the changes in rate constants from our single-channel experiments to our whole-cell dose-response curves, we simulated the macroscopic responses in the absence of desensitization. Specifically, we used each of the four kinetic schemes shown in Fig. 6A with two sequential GABA binding steps attached to C1 (Lema and Auerbach, 2006) to simulate whole-cell dose-response curves. For the purposes of the simulations, we also assumed that neither the mutation nor PRO altered the GABA binding affinity (GABA KD). Viewed from a qualitative perspective, our simulations successfully predicted the trends (Fig. 6, legend) but not the values or -fold shifts we observed in our whole-cell experiments (Fig. 1, legend). Compared with the WT - PRO condition, the MUT - PRO condition produced a 1.4-fold increase in the simulated GABA EC50. In wild-type receptors, PRO produced no changes, but in mutant receptors, PRO decreased the simulated GABA EC50 by 4.6-fold. In our actual whole-cell experiments, GABA EC50 values were increased by 2.5-fold (MUT - PRO versus WT - PRO), 7-fold (WT + PRO versus WT - PRO), and 40-fold (MUT + PRO versus MUT - PRO), respectively, indicating that without the effects on desensitization and GABA binding, our predicted shifts fall significantly short of our experimentally determined shifts. Similar comparisons of GABA ε values suggest that our simulations overestimated the effects of PRO on wild-type and mutant receptors versus what we observed in our whole-cell experiments. Therefore, we fully acknowledge the important role processes like desensitization play in GABAAR modulation by PRO (Bai et al., 1999) and the shaping of GABAergic synaptic responses (Jones and Westbrook, 1995; Bianchi and Macdonald, 2002). Based on these simulations, we also suggest that PRO primarily potentiates wild-type receptors by altering GABA binding and/or desensitization, whereas PRO has an additional synergistic effect on GABA-induced gating in mutant receptors carrying a γ2(L287A) mutation.

Discussion

We have measured the effect of a mutation in the GABAA receptor γ2 subunit M2-M3 linker on receptor gating by GABA and modulation by the general anesthetic PRO. The importance of this region in GABA-mediated channel gating has been clearly demonstrated previously in α and β subunits (Jones et al., 1995). The goal of this study was to better understand the role the homologous domain plays in the γ2 subunit. Because the M2-M3 linker residues in γ subunits are unlikely to contribute to either GABA or PRO binding sites, we focused our analysis on the allosteric effects produced by the mutation. Overall, we found that the γ2(L287A) mutation had modest negative effects on channel gating but strong positive effects on PRO modulation. We review these findings in terms of understanding receptor-gating defects and drug action on LGICs.

When we compared the activation of wild-type and γ2(L287A) mutant receptors by GABA, we found that the 2.5-fold increase in GABA EC50 of the mutant receptor was accompanied by a 1.9-fold decrease in mean open time. This decrease was underpinned by a 2.4-fold increase in fractional area of the shortest (0.7 ms) open time and the disappearance of the longest-lived (8 ms) open component. Our results suggest that the γ2(L287A) mutation produces an impairment of receptor function that can be described as a “low-efficacy” condition (Bianchi and Macdonald, 2003) or a “loss of function” perturbation (Wang et al., 1997). We discounted any effect the mutation may have had on GABA binding because the γ subunit is not required for GABA activation (αβ receptors; Jones et al., 1995).

The “loss of function” perturbation induced by the γ2(L287A) mutation is consistent with previous studies of M2-M3 linker function. At homologous and neighboring positions in the α subunit, the α2(L277A) and α2(K279A) mutations produced 51- and 4-fold increases in the GABA EC50, respectively (O'Shea and Harrison, 2000). Receptors containing α1(K279D) subunits showed a 10-fold decrease in the GABA EC50 (Kash et al., 2003). Lysine-to-methionine substitutions produced subtler effects on the GABA EC50, depending on whether the substitution was introduced into α1 (K278M, 4-fold), β2 (K279M, 5.2-fold), or the γ2 subunit (K289M, no effect; Bianchi et al., 2002; Hales et al., 2006; Krivoshein and Hess, 2006). Taken together, these findings suggest that all five M2-M3 linkers function in unison as a “hinge” region that allosterically transduces energy from agonist binding at the extracellular domains into channel opening at the transmembrane domains (Kash et al., 2003). In our current study, the loss of coupling efficiency introduced at a single locus was sufficient to impair channel gating even though the γ2(L287A) mutation was not located within an agonist binding subunit. In agreement with studies of the neighboring γ2(K289M) mutation (Bianchi et al., 2002; Hales et al., 2006; Krivoshein and Hess, 2006), we observed that the γ2(L287A) mutation resulted in the loss or reduction of the most stable long-lived openings at the single-channel level, with effects that were more pronounced than the naturally occurring substitution.

We then tested whether PRO could restore wild-type function to mutant receptors. Surprisingly, when we compared the actions of 10 μM PRO on wild-type and mutant receptors, we found that the resulting decrease in GABA EC50 was much larger in mutant receptors (∼40-fold) versus wild-type receptors (∼7-fold). This larger enhancement was accompanied by a 76% increase in the GABA ε value that was not observed in wild-type receptors. At the single-channel level, PRO increased the mean burst Po of mutant receptors by 1.7-through a 1.9-fold decrease in the mean burst closed time and a 5.8-fold increase in the mean burst open time. Specifically, PRO produced a 1.6-fold decrease in the longer 1.9-ms closed time component, 1.6- and 2.8-fold increases in the two shortest open time components, and produced the appearance of a predominant ∼25-ms open time component that was not detected in the MUT - PRO condition. In summary, not only did PRO introduce “high-efficacy” gating to mutant receptors, it appeared to stabilize a “high-Po” mode that was rarely observed in wild-type receptors.

Previous whole-cell studies have used supramaximal enhancements by allosteric modulators to reveal low-efficacy agonist-receptor combinations. For example, O'Shea et al. (2000) use PRO to decrease the EC50 and increase the ε value of the partial agonist piperidine-4-sulfonic acid in wild-type α1β1γ2 GABAARs. In another example, Krivoshein and Hess (2006) used the barbiturate phenobarbital to decrease EC50 and increase the ε value of GABA at α1β2γ2(K289M) GABAARs. Finally, Bianchi and Macdonald (2003) used the neurosteroid tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone to increase the ε value of GABA at α1β3δ GABAARs and of β-alanine at α1β3γ2 GABAARs.

Although PRO potentiated the responses of mutant receptors at all GABA concentrations, saturated responses of wild-type receptors proved to be resistant to further enhancement. Specifically, receptors in the WT + PRO condition showed no increase in GABA ε at the whole-cell level and no increase in the mean burst Po at the single-channel level. Because PRO produced no detectable changes in the intraburst kinetics (gating), we necessarily conclude that PRO acts at extraburst closures (desensitization) and/or at GABA binding steps that we could not observe at GABA saturation. Unfortunately, our multichannel patches did not allow us to distinguish between these possibilities in either mutant or wild-type receptors. In mutant receptors, our simulations (Fig. 6, legend) indicated these additional potentiation mechanisms undoubtedly complement the effects of PRO that we observed on channel gating.

Mutations in the M2-M3 linker region of several cysteine-loop receptors have been associated with disease states. For instance, in GABAARs, naturally occurring M2-M3 linker substitutions disrupt normal GABAA; R function in humans with a hereditary form of epilepsy (GEFS+; Baulac et al., 2001). In addition, M2-M3 linker substitutions in glycine receptor subunits produce hereditary hyperekplexia (Rajendra et al., 1994), and M2-M3 linker substitutions in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor produce channel-form myasthenia gravis (Sine et al., 1995). The increased sensitivity of M2-M3 linker mutants to potentiation by some positive allosteric modulators, as shown in this study and others (e.g., phenobarbital, Krivoshein and Hess, 2006; tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone, Bianchi and Macdonald, 2003; PRO, O'Shea and Harrison, 2000 and this study), suggests that low doses of positive allosteric modulators may be an effective treatment for diseases that at least partially target these low-efficacy synapses. For instance, subanesthetic doses of PRO have been used to temporarily reverse the neurological effects of hyperekplexia in a transgenic mouse model of the disease (O'Shea et al., 2004). Therefore, understanding the function of LGIC M2-M3 linkers and the mechanism of allosteric modulation offers hope for designing treatment strategies for low-efficacy channelopathies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Anthony Auerbach for support during the initial stages of this investigation.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant GM073959].

ABBREVIATIONS: PRO, propofol; GABAAR, type A GABA receptor; WT, wild-type α1β1γ2 GABAAR; MUT, mutant α1β1γ2(L278A) type A GABA receptor; M2-M3 linker, extracellular domain joining transmembrane domains 2 and 3; LGIC, ligand-gated ion channel; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; ε, relative efficacy; tcrit, critical time; C, closed; O, open.

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

References

- Angelotti TP and Macdonald RL (1993) Assembly of GABAA receptor subunits: alpha 1 beta 1 and alpha 1 beta 1 gamma 2S subunits produce unique ion channels with dissimilar single-channel properties. J Neurosci 13 1429-1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai D, Pennefather PS, MacDonald JF, and Orser BA (1999) The general anesthetic propofol slows deactivation and desensitization of GABAA receptors. J Neurosci 19 10635-10646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bali M and Akabas MH (2004) Defining the propofol binding site location on the GABAA receptor. Mol Pharmacol 65 68-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulac S, Huberfeld G, Gourfinkel-An I, Mitropoulou G, Beranger A, Prud'homme JF, Baulac M, Brice A, Bruzzone R, and LeGuern E (2001) First genetic evidence of GABAA receptor dysfunction in epilepsy: a mutation in the gamma2-subunit gene. Nat Genet 28 46-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi MT and Macdonald RL (2002) Slow phases of GABAA receptor desensitization: structural determinants and possible relevance for synaptic function. J Physiol 544 3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi MT and Macdonald RL (2003) Neurosteroids shift partial agonist activation of GABAA receptor channels from low- to high-efficacy gating patterns. J Neurosci 23 10934-10943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi MT, Song L, Zhang H, and Macdonald RL (2002) Two different mechanisms of disinhibition produced by GABAA receptor mutations linked to epilepsy in humans. J Neurosci 22 5321-5327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D (1998) Binding, gating, affinity and efficacy: the interpretation of structure-activity relationships for agonists and of the effects of mutating receptors. Br J Pharmacol 125 924-947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csanády L (2006) Statistical evaluation of ion-channel gating models based on distributions of log-likelihood ratios. Biophys J 90 3523-3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Castillo J and Katz B (1957) Interaction at end-plate receptors between different choline derivatives. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 146 369-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks NP and Lieb WR (1998) Which molecular targets are most relevant to general anaesthesia? Toxicol Lett 100-101 1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas KF and Macdonald RL (1999) GABAA receptor subunit gamma2 and delta subtypes confer unique kinetic properties on recombinant GABAA receptor currents in mouse fibroblasts. J Physiol 514 27-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales TG, Deeb TZ, Tang H, Bollan KA, King DP, Johnson SJ, and Connolly CN (2006) An asymmetric contribution to γ-aminobutyric type A receptor function of a conserved lysine within TM2-3 of α1, β2, and γ2 subunits. J Biol Chem 281 17034-17043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales TG and Lambert JJ (1991) The actions of propofol on inhibitory amino acid receptors of bovine adrenomedullary chromaffin cells and rodent central neurones. Br J Pharmacol 104 619-628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings HC Jr, Akabas MH, Goldstein PA, Trudell JR, Orser BA, and Harrison NL (2005) Emerging molecular mechanisms of general anesthetic action. Trends Pharmacol Sci 26 503-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MV, Harrison NL, Pritchett DB, and Hales TG (1995) Modulation of the GABAA receptor by propofol is independent of the γ subunit. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 274 962-968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MV and Westbrook GL (1995) Desensitized states prolong GABAA channel responses to brief agonist pulses. Neuron 15 181-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurd R, Arras M, Lambert S, Drexler B, Siegwart R, Crestani F, Zaugg M, Vogt KE, Ledermann B, Antkowiak B, and Rudolph U (2003) General anesthetic actions in vivo strongly attenuated by a point mutation in the GABAA receptor beta3 subunit. FASEB J 17 250-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kash TL, Jenkins A, Kelley JC, Trudell JR, and Harrison NL (2003) Coupling of agonist binding to channel gating in the GABAA receptor. Nature 421 272-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kash TL, Kim T, Trudell JR, and Harrison NL (2004) Evaluation of a proposed mechanism of ligand-gated ion channel activation in the GABAA and glycine receptors. Neurosci Lett 371 230-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keramidas A, Kash TL, and Harrison NL (2006) The pre-M1 segment of the alpha1 subunit is a transduction element in the activation of the GABAA receptor. J Physiol 575 11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasowski MD, Koltchine VV, Rick CE, Ye Q, Finn SE, and Harrison NL (1998) Propofol and other intravenous anesthetics have sites of action on the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor distinct from that for isoflurane. Mol Pharmacol 53 530-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivoshein AV and Hess GP (2006) On the mechanism of alleviation by phenobarbital of the malfunction of an epilepsy-linked GABAA receptor. Biochemistry 45 11632-11641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lema GM and Auerbach A (2006) Modes and models of GABAA receptor gating. J Physiol 572 183-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald RL, Rogers CJ, and Twyman RE (1989) Kinetic properties of the GABAA receptor main conductance state of mouse spinal cord neurones in culture. J Physiol 410 479-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuel NA and Davies CH (1998) Pharmacological modulation of GABAA receptor-mediated postsynaptic potentials in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus. Br J Pharmacol 125 1529-1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKernan RM and Whiting PJ (1996) Which GABAA-receptor subtypes really occur in the brain? Trends Neurosci 19 139-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody I and Pearce RA (2004) Diversity of inhibitory neurotransmission through GABAA receptors. Trends Neurosci 27 569-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen M and Smart TG (2007) Single-channel recording of ligand-gated ion channels. Nat Protoc 2 2826-2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell JG and Czajkowski C (2003) The GABAA receptor alpha 1 subunit Pro174-Asp191 segment is involved in GABA binding and channel gating. J Biol Chem 278 13166-13172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newland CF, Colquhoun D, and Cull-Candy SG (1991) Single channels activated by high concentrations of GABA in superior cervical ganglion neurones of the rat. J Physiol 432 203-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea SM, Becker L, Weiher H, Betz H, and Laube B (2004) Propofol restores the function of “hyperekplexic” mutant glycine receptors in Xenopus oocytes and mice. J Neurosci 24 2322-2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea SM and Harrison NL (2000) Arg-274 and Leu-277 of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor alpha 2 subunit define agonist efficacy and potency. J Biol Chem 275 22764-22768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea SM, Wong LC, and Harrison NL (2000) Propofol increases agonist efficacy at the GABAA receptor. Brain Res 852 344-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popescu G and Auerbach A (2003) Modal gating of NMDA receptors and the shape of their synaptic response. Nat Neurosci 6 476-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett DB, Sontheimer H, Shivers BD, Ymer S, Kettenmann H, Schofield PR, and Seeburg PH (1989) Importance of a novel GABAA receptor subunit for benzodiazepine pharmacology. Nature 338 582-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F (2004) Restoration of single-channel currents using the segmental k-means method based on hidden Markov modeling. Biophys J 86 1488-1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F, Auerbach A, and Sachs F (1996) Estimating single-channel kinetic parameters from idealized patch-clamp data containing missed events. Biophys J 70 264-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendra S, Lynch JW, Pierce KD, French CR, Barry PH, and Schofield PR (1994) Startle disease mutations reduce the agonist sensitivity of the human inhibitory glycine receptor. J Biol Chem 269 18739-18742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JE, Garcia PS, O'Toole KK, Derry JM, Bell SV, and Jenkins A (2007) A conserved tyrosine in the beta2 subunit M4 segment is a determinant of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor sensitivity to propofol. Anesthesiology 107 412-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM, Ohno K, Bouzat C, Auerbach A, Milone M, Pruitt JN, and Engel AG (1995) Mutation of the acetylcholine receptor alpha subunit causes a slow-channel myasthenic syndrome by enhancing agonist binding affinity. Neuron 15 229-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbach JH and Akk G (2001) Modulation of GABAA receptor channel gating by pentobarbital. J Physiol 537 715-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DA, Czajkowski C, and Jones MV (2004) An arginine involved in GABA binding and unbinding but not gating of the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci 24 2733-2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HL, Auerbach A, Bren N, Ohno K, Engel AG, and Sine SM (1997) Mutation in the M1 domain of the acetylcholine receptor alpha subunit decreases the rate of agonist dissociation. J Gen Physiol 109 757-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss DS and Magleby KL (1989) Gating scheme for single GABA-activated Cl-channels determined from stability plots, dwell-time distributions, and adjacent-interval durations. J Neurosci 9 1314-1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.