Summary

Morphogen gradients provide positional cues for cell fate specification and tissue patterning during embryonic development. One important aspect of morphogen function, the mechanism by which long-range signalling occurs, is still poorly understood. In Xenopus, members of the TGF-β family such as the nodal-related proteins and activin act as morphogens to induce mesoderm and endoderm. In an effort to understand the mechanisms and dynamics of morphogen gradient formation, we have used fluorescently labelled activin to study ligand distribution and Smad2/Smad4 bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) to analyse, in a quantitative manner, the cellular response to induction. Our results indicate that labelled activin travels exclusively through the extracellular space and that its range is influenced by numbers of type II activin receptors on responding cells. Inhibition of endocytosis, by means of a dominant-negative form of Rab5, blocks internalisation of labelled activin, but does not affect the ability of cells to respond to activin and does not significantly influence signalling range. Together, our data indicate that long-range signalling in the early Xenopus embryo, in contrast to some other developmental systems, occurs through extracellular movement of ligand. Signalling range is not regulated by endocytosis, but is influenced by numbers of cognate receptors on the surfaces of responding cells.

Keywords: Xenopus, TGF-β, Smads, Activin, Nodal-related proteins, Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC), Morphogen

INTRODUCTION

The mesoderm of the amphibian embryo forms from the equatorial region of the late blastula in response to signals derived from the vegetal hemisphere of the embryo (Heasman, 2006). These signals include members of the transforming growth factor type β (TGF-β) family such as Vg1, activin, the nodal-related proteins Xnr1, 2, 4, 5 and 6, and derrière (Birsoy et al., 2006; Jones et al., 1995; Joseph and Melton, 1997; Piepenburg et al., 2004; Smith, 1995; Sun et al., 1999; Takahashi et al., 2000; White et al., 2002). Two significant characteristics of these signals are that they can act at long range and that they behave as morphogens, eliciting different responses at different concentrations. These properties raise the question of how such molecules exert their long-range effects: what route do they take to traverse a field of responding cells?

This question has been addressed for TGF-β family members in several developing systems, and particularly in the Drosophila imaginal disc, where one proposal is that long-range signalling by Decapentaplegic (Dpp) occurs in this epithelial tissue by transcytosis (Entchev et al., 2000; Gonzalez-Gaitan and Jackle, 1999). According to this model, Dpp released by signalling cells would be taken up by adjacent cells by endocytosis, and after traversing these cells it would be released by exocytosis further away from the source, for the process then to be repeated. Although the data supporting transcytosis in Drosophila has been reinterpreted to suggest that Dpp exerts its long-range effects by diffusion (Belenkaya et al., 2004; Lander, 2007), endocytosis has been shown to play a role in regulating the range of Fgf8 signalling in the zebrafish neurectoderm (Scholpp and Brand, 2004). Another model involving endocytosis has been proposed for the transfer of Wingless (Wg), Hedgehog (Hh) and Dpp in the epithelium of the Drosophila imaginal wing disc, where morphogens have been suggested to exert long-range effects by means of cellular extensions (Hsiung et al., 2005; Incardona et al., 2000).

In this paper we investigate the dynamics of morphogen gradient formation in the Xenopus embryo and the role of endocytosis in regulating signalling range and in the cellular response to induction. We conclude that activin exerts its long-range effects through an extracellular route, that signalling range is influenced by the density of cognate receptors expressed on the surface of responding cells, and that Rab5-mediated endocytosis plays no significant role in morphogenetic signalling, neither with respect to transmission of the signal across a field of responding tissue and nor with respect to the cellular response to induction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Xenopus embryos and manipulation

Xenopus embryos were obtained, injected, dissected and staged as described (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1975; Tada et al., 1997). For animal cap assays, animal pole regions were transferred to agarose-coated dishes and cultured in 0.75× normal amphibian medium (NAM) (Slack, 1984) containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA). To investigate long-range signalling, animal pole regions were transferred to fibronectin-coated (10× dilution of 0.1% fibronectin from bovine plasma, Sigma) glass-bottomed dishes (MatTek) in 0.75× NAM, essentially as described (Williams et al., 2004). For `bead' experiments, Affi-Gel beads (Affi-Gel Blue Gel, Bio-Rad, 100-200 mesh) were incubated overnight with 1 mM Alexa488-activin protein at 4°C. For dissociated cell experiments, animal caps were dissociated in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free medium (75 mM Tris pH 7.5, 880 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 24 mM NaHCO3) for 30-45 minutes at room temperature and were then transferred to 0.75× NAM containing 0.2% BSA before being treated with activin. Dissociated cells were seeded onto a fibronectin-coated or 0.75 μg/ml E-cadherin-coated (recombinant human E-cadherin, R&D Systems) (Ogata et al., 2007) glass bottom dish (MatTek) in 0.75× NAM containing 0.2% BSA in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml Alexa488-activin or 5 μg/ml transferrin. For colocalisation assays, dissociated cells were derived from animal pole regions of uninjected embryos or embryos previously injected at the 1-cell stage with RNA encoding Rab4-, Rab5-, Rab7-, Rab11- or Hrs-Cherry. In some cases cells derived from uninjected embryos were treated with LysoTracker Red (Molecular Probes) for 1 hour before washing and imaging.

Real-time RT-PCR

Real-time RT-PCR using primers specific for Xbra, goosecoid, chordin, Fgf8 and ornithine decarboxylase (Odc) was carried out as described (Piepenburg et al., 2004). Primers for histone H4 were as described (Niehrs et al., 1994). All values were normalised to the level of Odc or histone H4 in each sample.

Constructs

cDNAs encoding activin βB, Xnr1, Xnr2, Xnr4, Smad2-VC155, Smad4-VN154-m9, histoneH2B-CFP, GFP-Gap43, Rab5S43N (kind gift from M. Gonzalez-Gaitan, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland), mCherry-xlRab4, mCherry-dmRab5, mCherry-dmRab7, mCherry-xlRab11 and mCherry-xlHrs were all cloned in the expression vector pCS2+. Xenopus laevis Rab4, Rab11 and Hrs cDNAs were obtained as IMAGE clones; mCherry cDNA was the kind gift from Roger Tsien (Howard Hughes Medical Institute and University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA). All such constructs were linearised with NotI and transcribed in vitro using SP6 RNA polymerase and the mMESSAGE mMACHINE kit (Ambion). GPI-CFP, mouse ActRIIB and Xenopus laevis DNActRIIB were cloned in the vector pSP64T BX, linearised with EcoRI and transcribed with SP6 RNA polymerase. Human dynaminK44E (kind gift from John Gurdon, Wellcome Trust/Cancer Research UK Gurdon Institute and Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK) in pGEMHE was linearised with NheI and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase. Smad2-VC155, Smad4-VN154-m9, histoneH2B-CFP, GPI-CFP and GFP-Gap43 were as described (Saka et al., 2008; Saka and Smith, 2007; Williams et al., 2004).

Labelled activin A preparation

Recombinant purified human activin A was labelled with Alexa Fluor 488 as follows: 2 mg of lyophilised activin A (154 nmol of protomers) was dissolved in 500 μl of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 with 20% acetonitrile. Neutral pH was chosen to promote preferential labelling at the N-terminus of the protein. Then 0.2 mg (311 nmol) of acetonitrile-solubilised Alexa Fluor 488 carboxylic acid succinimidyl ester (Invitrogen) was added to the protein and the reaction allowed to proceed for 1 hour in the dark. The sample was acidified with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and loaded onto a Vydac 214TP510 C4 reversed-phase column and eluted with a gradient of acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA. Peak fractions corresponding to labelled activin dimer were lyophilised under vacuum, solubilised in water, divided into four pools based on the level of labelling and stored at -20°C. Protein concentration was determined by quantitative amino acid analysis and the level of fluorophore incorporation was measured spectrophotometrically using a molar absorption coefficient for Alexa Fluor 488 of 71,000 at 500 nm. On average each activin dimer contained 0.7-1.4 fluorophores and mass-spectrometric analysis of the labelled samples showed at most three labels per dimer (data not shown).

Microscopy

Images in Figs 1, 5, 7, and supplementary material Figs S2A-E and S3 were taken using a Perkin Elmer Spinning Disc confocal microscope with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted microscope and a Hamamatsu ORCA ER camera. CFP protein was excited at 440 nm, VENUS BiFC at 514 nm, Alexa488 at 488 nm and Alexa594 at 568 nm. Pictures were acquired using UltraVIEW ERS software. Images in Figs 2, 3, 4, 6, 8 and supplementary material Fig. S2F-H were taken using an Olympus inverted FV1000 confocal microscope. CFP protein was excited at 458 nm, VENUS BiFC at 515 nm, mCherry at 564 nm and Alexa488 at 488 nm. Pictures were acquired using FluoView software. All confocal pictures were taken with a 40× oil objective and supplementary material Figs S2A-E and S3 represent a merged z-stack consisting of 15 slices, each 1 μm thick.

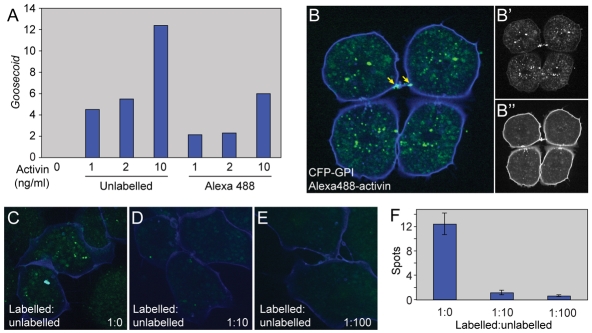

Fig. 1.

Alexa488-activin internalisation in dissociated animal cap cells. (A) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of dissected animal pole tissue treated with the indicated amounts of unlabelled activin or Alexa488-activin and cultured to the equivalent of the early gastrula stage. Bars indicate induction of Gsc. Note that unlabelled activin is approximately twice as effective as Alexa488-activin in inducing Gsc. This experiment was carried out four times, with similar results each time. (B-B″) Dissociated animal pole cells at the late blastula stage following incubation in Alexa488-activin for 1 hour before washing. Cells were derived from embryos that had previously been injected with the membrane marker CFP-GPI (blue). (B′) Alexa448 fluorescence alone. (B″) CFP-GPI fluorescence alone. Note Alexa488-activin accumulation at a cell-cell bridge (arrow in B). (C-F) Competition experiment in which cells are treated with Alexa488-activin in the presence of increasing amounts of unlabelled activin. (C) Internalisation of Alexa488-activin in the absence of unlabelled activin. (D) Internalisation of Alexa488-activin in the presence of a 10-fold excess of unlabelled activin. (E) Internalisation of Alexa488-activin in the presence of a 100-fold excess of unlabelled activin. (F) Quantitation of the experiment illustrated in C-E, showing mean numbers of aggregates (spots) of internalised Alexa488-activin. Values are means of 20-30 cells.

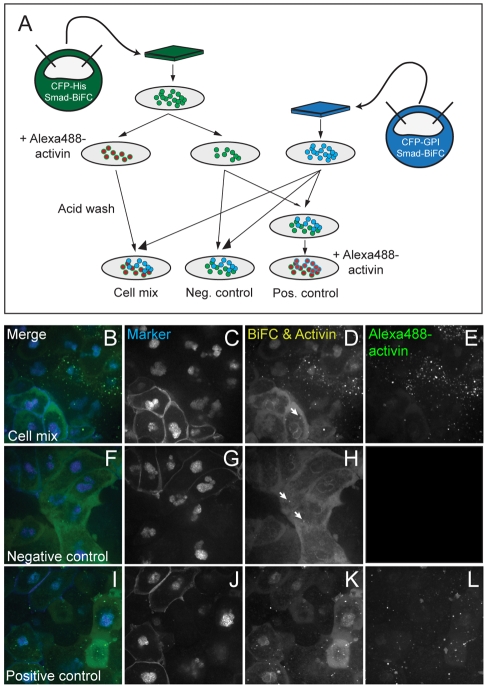

Fig. 5.

Mixed-cell assay for the analysis of activin signalling transfer. (A) Xenopus embryos at the 1-cell stage were injected with RNA encoding Smad2/4-BiFC constructs and either CFP-histoneH2B (green embryo) or CFP-GPI (blue embryo) as lineage markers. Animal pole regions were excised at the late blastula stage and dissociated into single cell suspensions. One third of the cells marked with CFP-histoneH2B were treated for 1 hour with Alexa488-activin and then washed four times, including a 30-second acidic wash to remove surface-bound protein. A similar number of cells from the same population was not treated with Alexa488-activin but was otherwise treated identically (including the wash steps). Both groups of cells were mixed with dissociated blastomeres derived from embryos labelled with CFP-GPI and CFP-histoneH2B and then allowed to adhere before being transferred to fibronectin-coated glass-bottomed dishes. One portion of the `control' mix, in which neither population of cells had been previously treated with activin, was exposed to Alexa488-activin for 1 hour to confirm that cells remained healthy and could still respond to induction. (B-L) Confocal images of the experiments described in A. (B,F,I) Merged images showing CFP markers in blue and Smad2/4-BiFC and Alexa488-activin in green. (C,G,J) CFP markers viewed at an excitation wavelength of 440 nm. (D,H,K) Smad2/4-BiFC and Alexa488-activin are visible at an excitation wavelength of 514 nm. Note that Alexa488-activin and Smad2/4-BiFC are not detectable in untreated cells that are positioned adjacent to cells treated with labelled activin (D). Rather, levels of nuclear fluorescence resemble those in control samples (H), where a weak signal is present only in the cytoplasm and on the nuclear membrane (Saka et al., 2007). Note the Smad2/4-BiFC aggregates in D and H (arrows). Treatment of control samples with Alexa488-activin causes nuclear Smad2/4-BiFC accumulation and one can detect labelled activin within cells (K). (E,L) Excitation at a wavelength of 488 nm allows one to visualise Alexa488-activin alone. Note that labelled activin cannot be passed from cell to cell. This experiment was carried out four times, with similar results each time.

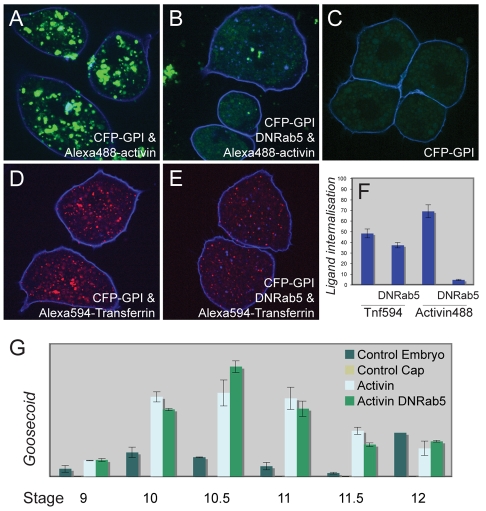

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of endocytosis by Rab5S43N does not prevent gene induction in response to activin. (A) Animal pole blastomeres derived at the late blastula stage from an embryo previously injected with RNA encoding lactate dehydrogenase (Ldh; control RNA) and then cultured in the presence of Alexa488-activin. Note the internalised fluorescent activin. (B) Animal pole blastomeres derived at the late blastula stage from embryos previously injected with RNA encoding Rab5S43N (DNRab5) and then cultured in the presence of Alexa488-activin as in A. Note the strong inhibition of internalisation of labelled activin. (C) Control animal pole blastomeres derived as in A but not exposed to Alexa488-activin. Note the yolk autofluorescence. (D) Animal pole blastomeres were derived from embryos injected with RNAs encoding Ldh and the transferrin receptor and were then cultured in the presence of Alexa594-transferrin. Note the internalised transferrin. (E) Animal pole blastomeres were derived from embryos injected with RNAs encoding Rab5S43N and the transferrin receptor and were then cultured in the presence of Alexa594-transferrin. Note the slight inhibition of internalisation of fluorescent transferrin. All embryos in A-E were also injected with RNA encoding the CFP-GPI membrane marker (blue). (F) Quantitation of experiments illustrated in A-E. (G) Expression of Gsc in whole embryos and in animal pole regions treated as indicated and analysed by real-time quantitative PCR at the indicated stages (n=2). Other target genes are shown in Fig. S4A,B in the supplementary material (n=2). Bars represent standard errors of technical replicates. Three additional experiments of this sort were performed in which gene expression analysis was carried out at a single time point; these gave similar results.

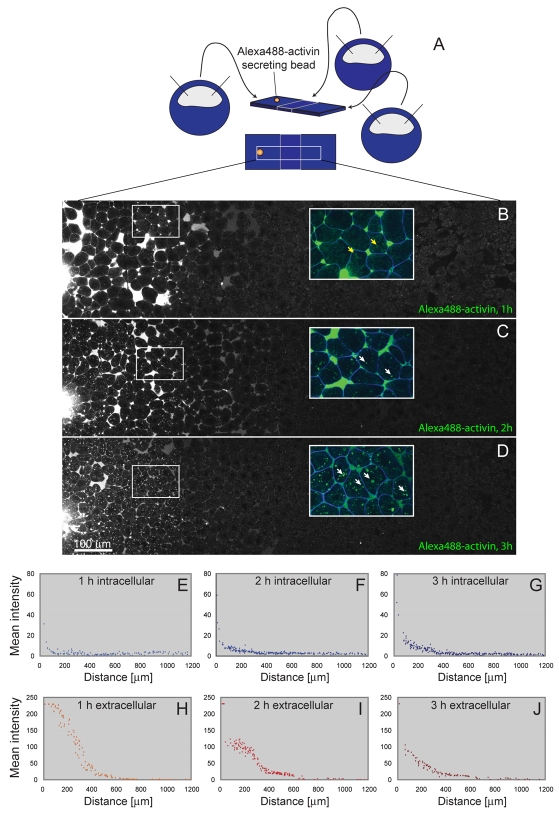

Fig. 2.

Long-range signalling by Alexa488-activin. (A) Diagram showing the experimental design. Embryos were injected with RNAs encoding the indicated markers at the 1-cell stage and animal pole regions were dissected at late blastula stage 9 and positioned next to each other on a fibronectin-coated glass-bottomed dish. After allowing time to heal, an Alexa488-activin-soaked bead was placed in the middle of the left-hand animal pole region and conjugates were cultured for 1 (B), 2 (C) or 3 (D) hours before imaging. (B-D) Images of conjugates corresponding to the region outlined in A, with Alexa488-activin being secreted from the bead on the left. Each image is a montage created from four separate pictures and shows Alexa488-activin signal only (n=8). Note the large amounts of extracellular Alexa488-activin in B and C (1-2 hours), and increasing amounts of intracellular fluorescence in C and D (2-3 hours). Insets represent enlargements from the outlined areas, with membrane marker CFP-GPI in blue and Alexa488-activin in green. Yellow arrows in B indicate weak autofluorescence derived from yolk; white arrows in C and D indicate intracellular Alexa488-activin aggregates. (E-J) Quantitation of levels of Alexa488-activin at 1 hour (E,H), 2 hours (F,I) and 3 hours (G,J) in extracellular space (H-J) and intracellularly (E-G). This experiment was carried out four times, with similar results each time. Fluorescence was quantified with Volocity software as a mean of random manually drawn regions of interest (ROIs), defined as intracellular or extracellular relative to the coexpressed membrane marker CFP-GPI. Between 93 and 225 ROIs were counted for each graph, with the area studied representing 1200 μm. The total quantified area represents the 1200 μm-wide clippings shown in B-D. Note that elevated levels of extracellular fluorescence, at positions remote from the bead, are detected before one can detect elevated levels of intracellular fluorescence.

Fig. 3.

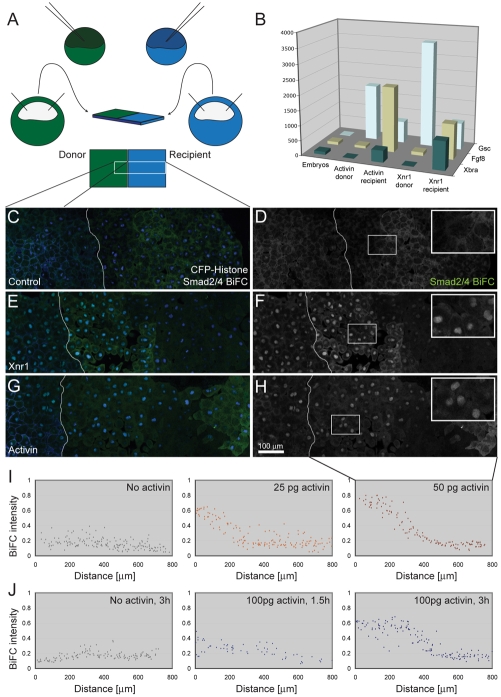

Long-range induction of Smad2/4-BiFC signalling in Xenopus animal pole regions. (A) Diagram showing the experimental design. Embryos at the 1-cell stage were injected with RNA encoding cell lineage markers together with RNA encoding Smad2/4-BiFC. The embryo depicted in green was also injected with RNA encoding activin or Xnr1. Animal pole regions were dissected at the late blastula stage and juxtaposed on fibronectin-coated glass-bottomed dishes for imaging, as shown. (B) Animal pole regions prepared as shown in A were cultured for 4 hours and then dissected apart before RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR analysis for the expression of Gsc, Fgf8 and Xbra. This experiment was carried out once using activin as an inducer and four times using Xnr1. Note that both activin and Xnr1 are able to induce the expression of all three genes in `recipient' tissue. (C-H) Images of conjugates corresponding to the region outlined in A (n=3). White lines represent the border between two explants. Images are montages created from three fields of view. (C) Control explants expressing CFP-GPI membrane marker and CFP-histoneH2B chromatin marker (both in blue) together with Smad2/4-BiFC constructs (green). In the absence of activin or Xnr1, levels of BiFC fluorescence do not rise above background (Saka et al., 2007). (E) Image of a conjugate identical to that in C, except that the left-hand animal pole region also expresses Xnr1. Note the activation of nuclear Smad2/4-BiFC in the right-hand animal pole region. (G) Image of a conjugate identical to that in C, except that the left-hand animal pole region also expresses activin. (D,F,H) Smad2/4-BiFC fluorescence of sample shown in C,E and G, respectively. Insets represent magnification of outlined areas. Note the activation of nuclear Smad2/4-BiFC in the right-hand animal pole region. (I) Measurements of nuclear BiFC fluorescence intensity relative to CFP-histoneH2B in recipient (right-hand) animal pole regions only. The first graph shows a negative control, the second an experiment in which animal pole regions were derived from an embryo injected with 25 pg activin RNA, and the third an experiment using 50 pg activin RNA. The left side of the graph represents the side of the explant closest to the source of ligand. Quantitation was performed with Volocity software, selecting all nuclei by automatic choice of fluorescence threshold and normalising to CFP-histoneH2B (n=5). (J) Measurements of BiFC fluorescence intensity in recipient (right-hand) animal pole regions at different times after juxtaposition of responding tissue with animal pole regions derived from an embryo injected with no activin (control) or 100 pg activin RNA. Note that a response is visible within 1.5 hours (compare with images in Fig. S4F-H in the supplementary material) (n=2).

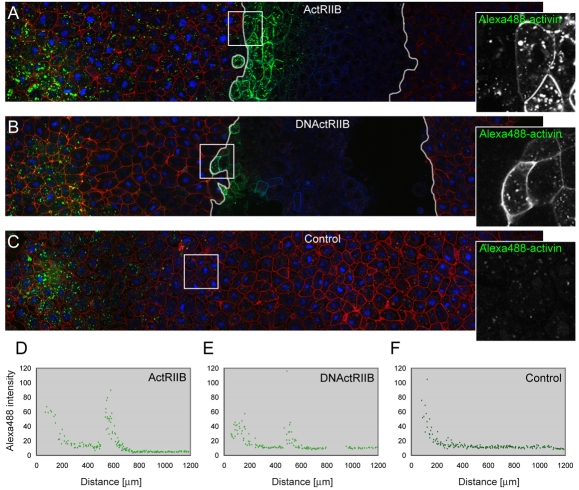

Fig. 4.

Overexpression of ActRIIB blocks activin passage and enhances its cellular uptake. (A-C) Three animal pole regions were juxtaposed such that the left-hand tissue acted as a source of Alexa488-activin (provided by a bead soaked in fluorescent activin, located outside of the depicted confocal section), the middle piece was the test tissue, and the right-hand tissue functioned as recipient tissue. White lines in A and B represent boundaries between the different regions. Alexa488 signal is green, mCherry membrane marker is red (control tissue), and CFP-histoneH2B (control) and CFP-GPI membrane marker (test tissue) are blue. This experiment was carried out four times, with similar results each time. (A) Overexpression of wild-type ActRIIB in the middle explant leads to the accumulation of Alexa488-activin close to the junction between the two populations of cells, both at the cell surface and within cells (see also Fig. S3 in the supplementary material). (B) Overexpression of a truncated form of ActRIIB (DNActRIIB) in the middle explant leads to the accumulation of Alexa488-activin close to the junction between these cells and the left-hand explant. Fluorescence is visible both at the cell surface and within cells (see also Fig. S3 in the supplementary material). (C) Control for A and B in which all three animal pole tissues express mCherry membrane marker and CFP-histoneH2B only. Images on right represent enlargements of outlined areas. (D-F) Quantitation of intracellular Alexa488-activin fluorescence for pictures shown in A-C (for methods see Fig. 2).

Fig. 6.

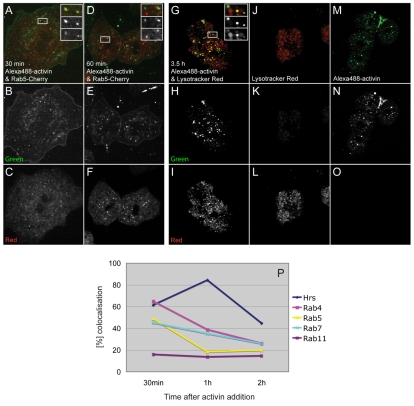

Colocalisation studies using Alexa488-activin. (A-F) Confocal images of dissociated Xenopus animal pole blastomeres incubated with Alexa488-activin (green). Early endosomes are marked by the expression of a Rab5-Cherry construct (red). (A-C) Images acquired 30 minutes after a 10-minute treatment with labelled activin. (D-F) Images acquired 60 minutes after a 10-minute activin treatment. (G-I) Confocal images of dissociated animal cap cells treated with Alexa488-activin (green) and counterstained with LysoTracker Red. Images were acquired 3.5 hours after a 10-minute treatment with labelled activin. Insets in A,D,G represent the area outlined in the main part of the image, and show a merged image (top) and images taken using green (middle) and red (lower) fluorescence filters separately. (J-L) Control cells not exposed to Alexa488-activin and counterstained with LysoTracker Red. (M-O) Cells treated with Alexa488-activin only. Images in B,E,H,K,M were acquired using 488 nm excitation and a narrow 521-531 nm filter for green fluorescence emission to reduce background. Images in C,F,I,L,O were acquired using 561 nm excitation and a narrow 601-613 nm filter for red fluorescence emission. All cells were seeded on glass-bottomed dishes that had been coated previously with E-cadherin. (P) Quantitation of colocalisation of Alexa488-activin with the indicated fluorescent markers. An average of ten cells was counted for each point, with each cell containing at least ten aggregates of Alexa488-activin.

Fig. 8.

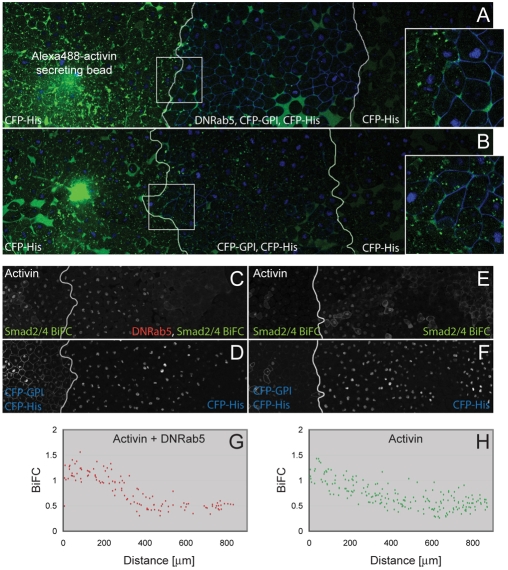

Effect of Rab5S43N on activin passage and long-range signalling. (A) Three juxtaposed animal pole regions with white lines representing borders between explants. A bead previously soaked in Alexa488-activin was implanted in the left-hand animal cap and the middle section expressed both CFP-GPI and Rab5S43N. All three explants expressed CFP-histoneH2B. Note the extracellular Alexa488-activin in the middle section at a distance from the bead (n=7). (B) Control for A in which the middle section does not express Rab5S43N. Images on right represent enlargements of outlined areas. (C-F) Three juxtaposed animal pole regions in which all tissues expressed Smad2/4-BiFC reagents and CFP-histoneH2B, and the left-hand animal cap expressed activin and CFP-GPI (n=9). In C and D the centre and right-hand animal pole regions expressed Rab5S43N. (C,E) Fluorescence derived from Smad2/4-BiFC. Note the long-range signalling and activation of Smad2/4-BiFC even in the presence of Rab5S43N. (D,F) CFP-histoneH2B fluorescence to reveal nuclei. (G,H) Quantitation of Smad2/4-BiFC fluorescence normalised to CFP-histoneH2B (as described in Fig. 3) in the samples illustrated in C,D (G) and E,F (H) (n=3).

Fluorescence was quantified using Volocity software and is presented as the mean values of manually drawn regions of interest (ROIs) identified by referring to the coexpressed membrane marker CFP-GPI (Fig. 2) or by automatic selection of all CFP-histoneH2B-positive nuclei and normalised to CFP-histone marker (Fig. 3).

RESULTS

Rapid extracellular spreading of Alexa488-activin is followed by slower internalisation

The most direct approach to investigate the role of endocytosis in morphogenetic signalling is to use fluorescently labelled proteins and live cell imaging. In past work we have made use of an EGFP-Xnr2 fusion protein to follow the passage of a TGF-β family member through Xenopus animal pole explants (Williams et al., 2004), and found no evidence for ligand internalisation. However, it is possible that this approach is not sufficiently sensitive, and in addition, without accurate knowledge of ligand concentrations, it is difficult to obtain quantitative results. In an effort to address these concerns, we have instead labelled activin protein with Alexa Fluor 488. Activin can act as a potent long-range morphogen (Jones et al., 1996) and our experiments show that this labelled activin retains ∼50% of its biological activity (Fig. 1A) and that it is internalised by isolated Xenopus animal pole blastomeres in a specific manner (Fig. 1B-F). Under our experimental conditions we can readily visualise an extracellular concentration of Alexa488-activin of 250 ng/ml and lower concentrations might also be detectable (see Fig. S1A-E in the supplementary material).

To investigate the ability of this labelled activin to traverse a field of responding cells, we soaked Affi-Gel (Bio-Rad) beads in Alexa488-activin and introduced them into animal pole regions that had been allowed to adhere to a fibronectin-coated substrate (Williams et al., 2004). To expand the space available for ligand movement, the animal pole regions were juxtaposed with two additional animal caps (Fig. 2A). Alexa488-activin was distributed in a diffuse manner in the extracellular space 1 hour after introducing the bead, with little fluorescence visible within cells (Fig. 2B,E,H). Fluorescent activin was also located in discrete aggregates within cells 1 hour later, although extracellular levels were still higher than intracellular levels (Fig. 2C,F,I). The number of internalised Alexa488-activin aggregates increased further over the next hour, although the amount of extracellular activin, derived from the implanted bead, decreased (Fig. 2D,G,J).

This temporal analysis of activin distribution, in which the appearance of extracellular ligand precedes that of internalised material, is consistent with the idea that activin can spread from its source via an extracellular route.

Smad2/4 bimolecular fluorescence complementation provides a direct read-out of long-range signalling by TGF-β family members

In an effort to visualise a direct response to long-range TGF-β signalling, we have turned to Smad2-Smad4 bimolecular fluorescence complementation (Smad2/4-BiFC). This approach has already been used to visualise Smad signalling in cells of the Xenopus embryo (Saka et al., 2007), and it provides a direct, quantitative and rapid read-out of activin-like signalling, with a better signal-to-noise ratio than obtained by monitoring the nuclear translocation of GFP-Smad2 (Bourillot et al., 2002; Grimm and Gurdon, 2002; Kinoshita et al., 2006). Animal pole explants were therefore derived from embryos co-injected with mRNAs encoding (1) Smad2/4-BiFC constructs (Saka et al., 2007); (2) activin or Xnr1; and (3) fluorescent markers for membrane and for chromatin (CFP-GPI and CFP-histoneH2B, respectively). These pieces of tissue were juxtaposed with animal pole tissue derived from embryos co-injected with RNAs encoding the Smad2/4-BiFC constructs and CFP-histoneH2B (Fig. 3A) and the conjugates were cultured on a fibronectin-coated surface for 4 hours before being viewed live under the confocal microscope. The ability of activin and Xnr1 to activate gene expression at long range was confirmed by RT-PCR analysis of animal pole regions that were separated after 4 hours of culture (Fig. 3B).

In the absence of TGF-β ligands, Smad BiFC activation was not detectable in signalling or responding cells (Fig. 3C,D), but in the presence of activin or Xnr1, nuclear BiFC fluorescence was observed in both tissues (Fig. 3E-H). In the responding tissue, levels of nuclear Smad2/4-BiFC fluorescence decreased with increasing distance from the signalling cells, and higher concentrations of injected activin RNA increased the range of BiFC activation (Fig. 3I). Quantitation of experiments such as these is complicated by the fact that there is significant `noise' in the system; Smad2/4-BiFC levels in adjacent cells can differ significantly. Nevertheless, timecourse experiments suggest that the range of activin signalling does not expand significantly between 1.5 and 3 hours after animal cap juxtaposition, but that the intensity of Smad BiFC does increase (Fig. 3J and see Fig. S2F-H in the supplementary material). These observations indicate that the establishment of a stable activin gradient occurs within 90 minutes. They also suggest that cells can increase their level of response over a longer period than this, although this observation may derive in part from the stability of Smad2/4-BiFC complexes (Saka et al., 2007).

Together, our results indicate that Smad2/4-BiFC provides a fast and direct means for detecting long-range signalling by members of the TGF-β family. Additional experiments revealed that other nodal-related proteins such as Xnr2 and Xnr4 also induce nuclear Smad BiFC activation, albeit less efficiently than activin and Xnr1 (see Fig. S2 in the supplementary material).

Increasing numbers of cell surface receptors cause signalling range to decrease

In an effort to ask to what extent receptor-mediated endocytosis influences activin signalling range, we overexpressed wild-type or truncated forms of the type IIB activin receptor (ActRIIB) in tissue that is positioned between a source of activin and a population of responding cells. Activin, like other TGF-β family members, signals by interacting first with a type II receptor, which then associates with and phosphorylates a type I receptor serine/threonine kinase. This activated type I receptor goes on to phosphorylate the receptor-regulated Smads 2 or 3, which associate with Smad4 and enter the nucleus to regulate transcription (Armes and Smith, 1997; Wu and Hill, 2009).

Overexpression of both the wild-type activin receptor ActRIIB and a truncated form lacking only the intracellular domain (DNActRIIB) caused Alexa488-activin to accumulate around and within cells close to the source of the signal (Fig. 4) and long-range signalling, monitored by Smad2/4-BiFC, was not observed (DNActRIIB) or was significantly reduced (ActRIIB; see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material). The increased internalisation of Alexa488-activin caused by expression of the activin receptors suggests that this internalisation is a specific process rather than non-specific phagocytosis of extracellular material.

Overexpression of the wild-type activin type II receptor does not lead to increased signalling activity in responding cells, as judged by the intensity of Smad2/4-BiFC (see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material and data not shown). It is possible that levels of type I, rather than type II, receptor are limiting in these cells, because overexpression of the type I receptor Thickveins in Drosophila does sensitise cells to levels of Dpp (Lecuit and Cohen, 1998). Future experiments will ask how the downregulation of activin receptors influences activin signalling range.

The failure of increased receptor density to extend signalling range suggests that activin does not exert its long-range effects by transcytosis. Indeed, the dramatic reduction in signalling range suggests that receptor-mediated endocytosis in Xenopus restricts the passage of activin, as is also observed for Fgf8 in the developing zebrafish neurectoderm (Scholpp and Brand, 2004).

Activin does not spread via transcytosis in Xenopus blastula cells

To investigate in more detail whether internalised activin can transfer from one cell to another, we designed a cell mixing assay in which cells that had previously been treated with activin were mixed with untreated cells. In the course of these experiments, animal pole blastomeres derived from embryos at the late blastula stage were dissociated and incubated in Alexa488-activin before being acid-washed to remove any adherent ligand. These cells were mixed with dissociated cells that had not been incubated with activin and they were allowed to aggregate for at least 3 hours before imaging (Fig. 5A). The two populations could be distinguished by the expression of different fluorescent cell markers, and both were expressing our Smad2/4-BiFC constructs (Fig. 5A).

Under these conditions, we were unable to observe the transfer of labelled activin from treated to untreated cells and nor could we observe nuclear Smad2/4-BiFC in untreated cells (Fig. 5B-H). As a control, to ensure that cells remained healthy and susceptible to newly exocytosed activin throughout the procedure, two untreated populations of cells were mixed and treated with Alexa488-activin during aggregation (Fig. 5A). These cells internalised fluorescent activin and showed nuclear accumulation of Smad2/4-BiFC (Fig. 5I-L). These experiments suggest that passage of activin via transcytosis does not occur in Xenopus blastomeres.

Internalised Alexa488-activin associates with Rab5-containing endosomes and then with lysosomes

In an effort to investigate the fate of internalised Alexa488-activin, we next studied its intracellular localisation in Xenopus animal pole blastomeres. Ligand-receptor complexes of TGF-β family members have been suggested to associate with clathrin-coated endosomes that fuse with Rab5-positive early endosomes shortly after budding from the cytoplasmic membrane (Zerial and McBride, 2001). We investigated this process in the early Xenopus embryo by isolating animal pole blastomeres from embryos expressing tagged endocytosis markers. Such blastomeres were incubated in Alexa488-activin for 20 minutes and examined at intervals thereafter. After 10 minutes, 50% of intracellular Alexa488-activin aggregates were associated with Rab5, a marker of early endosomes (Fig. 6A-C,P), or Rab7, a marker of late endosomes or multi-vesicular bodies (MVBs). Over 60% of aggregates colocalised with Rab4, which is expressed in early endosomes and is involved in degradation and in the fast recycling pathway (Sonnichsen et al., 2000), or Hrs, which marks the degradation pathway from early endosomes onwards (McCaffrey et al., 2001; Saksena et al., 2007; Williams and Urbe, 2007). These figures decreased to ∼20% for Rab5 and less than 40% for Rab4 and Rab7 over the next 30 minutes, whereas colocalisation with Hrs increased to over 80% (Fig. 6D-F,P). By 3.5 hours, 93% of Alexa488-activin particles were associated with lysosomes, as revealed by the colocalisation of activin-Alexa488 with LysoTracker Red (Fig. 6G-O).

Although Rab11 can be detected with Rab7 on MVBs (Bottger et al., 1996), this is predominantly a marker of recycling vesicles (Sonnichsen et al., 2000). At all times tested, only ∼10% of Alexa488-activin particles associated with Rab11 (Fig. 6P). Together, these observations suggest that the great majority of intracellular activin is targeted for degradation rather than for transcytosis.

Ligand internalisation is not required for gene induction or for long-range signalling

In a final effort to investigate the role of endocytosis in long-range signalling in the Xenopus embryo, we turned to inhibitors of endocytosis. The results described above indicate that internalised activin associates with Rab5, so we have made use of Rab5S43N, a dominant-negative form of Rab5. Animal pole blastomeres derived from embryos injected with RNA encoding Rab5S43N failed to internalise Alexa488-activin (Fig. 7A-C) and, in an additional assay, the internalisation of transferrin into animal pole blastomeres expressing the transferrin receptor was also attenuated (Fig. 7D,E). Inhibition of activin uptake was more effective than that of transferrin (Fig. 7F), perhaps because the transferrin receptor was overexpressed to high levels. Other inhibitors of endocytosis, including dynaminK44E and dynaminK535A (dominant-negative versions of dynamin), phenylarsine oxide and monodansyl cadaverine, were less effective than Rab5S43N or were too toxic (see Fig. S4 in the supplementary material and data not shown).

Our first series of experiments asked whether endocytosis is required for the induction of gene expression by activin. This is a significant issue because there is no consensus concerning the necessity for endocytosis for TGF-β signalling; some investigations have suggested that endocytosis is essential (Hu et al., 2008; Jullien and Gurdon, 2005; Kinoshita et al., 2006; Penheiter et al., 2002; Runyan et al., 2005), whereas others indicate that TGF-β or activin signalling can occur from the cytoplasmic membrane (Chen et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2002; Panopoulou et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2004; Zwaagstra et al., 2001). In our experiments, we treated animal pole regions derived from embryos expressing Rab5S43N with activin and went on to measure the activation of target genes, including Gsc, Xbra and chordin, at different developmental stages. The ability of the dominant-negative form of Rab5 to inhibit the internalisation of activin was confirmed in parallel experiments (Fig. 7A-F and data not shown). In no case was target gene expression inhibited by Rab5S43N. Indeed, expression of Xbra was slightly elevated after stage 10.5 in blastomeres in which Rab5 function was inhibited, perhaps as an indirect effect of endocytosis-dependent signalling events. Interestingly, a similar enhancement of TGF-β signalling has been observed in Mv1Lu cells treated with inhibitors of clathrin-dependent endocytosis (Chen et al., 2009). Together, these results suggest that in Xenopus animal pole region endocytosis is not required for the activation of gene expression by activin (Fig. 7G and see Fig. S4 in the supplementary material).

At first sight our results using Rab5S43N are at odds with reports that dynaminK44E can inhibit activin signalling in Xenopus embryonic tissue (Jullien and Gurdon, 2005; Kinoshita et al., 2006). In searching for an explanation, we first note that the two inhibitory constructs target different components of the endocytic pathway. In addition, whereas previous work tested the efficacy of dynaminK44E by monitoring the internalisation of exogenously expressed activin receptors, or of labelled transferrin via an exogenously expressed transferrin receptor (Jullien and Gurdon, 2005; Kinoshita et al., 2006), our work demonstrates that dynaminK44E (in contrast to Rab5S43N) has little effect on the uptake of Alexa488-activin via endogenous receptors (data not shown). Finally, our quantitative RT-PCR experiments revealed that dynaminK44E causes only a slight decrease in the expression of Xbra in response to activin, with no effect on the expression of goosecoid (see Fig. S4C in the supplementary material and data not shown). Similar results were obtained using Smad2/4-BiFC, which provides single-cell resolution of the response to activin with a higher signal-to-noise ratio than is obtained with Smad2-GFP imaging. Together, these data are consistent with our conclusion that endocytosis is not required for the cellular response to activin.

We next asked whether endocytosis is required for long-range signalling. In the first experiment, animal pole tissue expressing Rab5S43N was positioned between an animal pole region containing a bead soaked in Alexa488-activin and an untreated animal pole region. Conjugates were cultured for 4 hours before the distribution of fluorescent activin was analysed. In control experiments, and as previously described, Alexa488-activin was detectable many cell diameters from the activin source, with ligand present both in the extracellular space and within cells (Fig. 2C,D and Fig. 8B). Fluorescent activin was also able to traverse cells expressing Rab5S43N, but in such cases Alexa488-activin was exclusively extracellular (Fig. 8A).

In another set of experiments we examined the influence of endocytosis on activin signalling range by juxtaposing animal pole regions derived from embryos expressing activin mRNA with responding tissue expressing Rab5S43N. Both groups of cells also expressed Smad2/4-BiFC constructs, which confirmed that activin can signal in cells in which endocytosis is inhibited and again revealed that activin can exert its effects at long range even in the absence of endocytosis (Fig. 8B-G).

DISCUSSION

Mesoderm formation in the early embryo of Xenopus laevis requires the activities of at least eight distinct members of the TGF-β family, all of which are thought to act in a concentration-dependent manner, and many of which can act at long range (Agius et al., 2000; Green, 2002; Sun et al., 1999; Takahashi et al., 2000). Proper mesoderm formation requires that the actions of these morphogens are coordinated such that concentration gradients are generated in a reliable and reproducible manner. In this paper we study the way in which these gradients are established.

Activin travels through an extracellular route

Our results suggest that activin travels through an extracellular route that does not involve transcytosis. Thus, Alexa488-activin can be detected extracellularly remote from its source within 1 hour, well before it can be visualised intracellularly, at about 2 hours (Fig. 2). In addition, animal pole blastomeres that had been preloaded with Alexa488-activin could not pass ligand to adjacent unloaded cells, nor could they induce Smad2/4-BiFC in such cells (Fig. 5). And finally, although inhibition of Rab5-mediated endocytosis does prevent internalisation of Alexa488-activin (Fig. 7A-C,F and Fig. 8A), it does not prevent its passage through responding tissue (Fig. 8A) and nor does it significantly affect its signalling range (Fig. 8C-H) or the cellular response to induction (Fig. 7G, see Fig. S4A,B in the supplementary material and below). Indeed, our results suggest that internalised activin is destined for lysosomes rather than for re-secretion and long-range signalling (Fig. 6). These results are consistent with some aspects of previous work (Kinoshita et al., 2006), but extend it by visualising activin ligand directly.

Our efforts to fit the extracellular distribution of Alexa488-activin to an exponential or power trend line have failed, perhaps because the bead used to supply the activin does not represent a continuous source (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material and data not shown). We do observe, however, that the distribution of internalised activin fits a power trend line to a good approximation from 2 hours onwards. The elevated decay of activin close to the source of the ligand suggests that the rate of intracellular degradation exceeds the rate of uptake, because we show that significant amounts of activin do not leave the cell after endocytosis (Figs 5 and 6).

Our conclusion that long-range signalling in Xenopus occurs through an extracellular route differs from the suggestion made for the Drosophila imaginal wing disc that Dpp might traverse cells by transcytosis (Entchev et al., 2000; Gonzalez-Gaitan and Jackle, 1999). We note, however, that the Drosophila imaginal disc consists of a closely packed polarised epithelium, whereas cells in the Xenopus blastula are arranged as a looser mesenchyme. Contacts in the Xenopus tissue are likely to be less stable and fewer in number than in the imaginal disc, so that long-range signalling by transcytosis is likely to be much less efficient in this tissue.

Receptor density but not Rab5-mediated endocytosis influences signalling range

In some respects our results are consistent with those of Scholpp and Brand (Scholpp and Brand, 2004), who find that inhibiting internalisation of Fgf8 in the neurectoderm of the zebrafish extends its signalling range, while elevating internalisation reduces it. Consistent with these results, our data show that an increase of the ligand-receptor interaction surface due to overexpression of an activin receptor causes the accumulation of ligand inside and at the surface of responding cells, and this prevents its movement further into responding tissue (Fig. 4). Similarly, in Drosophila, levels of a type I receptor limits the range of Dpp signalling (Lecuit and Cohen, 1998). Together, our data remain consistent with a model in which long-range signalling by morphogens occurs by simple extracellular diffusion (Belenkaya et al., 2004; Lander et al., 2002).

However, in contrast to Scholpp and Brand (Scholpp and Brand, 2004), we find that inhibition of activin internalisation does not significantly extend its signalling range (Fig. 8G,H). One explanation might be that the two systems, zebrafish neurectoderm and Xenopus animal pole tissue, differ with respect to the space available for ligand distribution. In particular, our system provides a space that is effectively infinite, because the morphogen can eventually diffuse beyond the edges of the explant. The significance of this extended space is under investigation, and we also note that the signalling ranges of different ligands (Fgf8 and activin) in different tissues (neurectoderm and animal pole tissue) may well be subject to different types of regulation.

Receptor-mediated endocytosis is not required for gene activation

Our experiments also reveal that Rab5-mediated endocytosis is not required for the activation of the activin signal transduction pathway, as revealed both by Smad2/4-BiFC (Fig. 8C-H) and by the induction of gene expression (Fig. 7G and see Fig. S4A,B in the supplementary material). The elevation of Xbra expression associated with the inhibition of Rab5 activity (see Fig. S4B in the supplementary material) is likely to be due to an indirect effect.

There is no consensus in the literature about the requirement for endocytosis in growth factor function. There are likely to be differences between different ligands and different cell types, and the point at which the pathway is inhibited might also be significant. Consistent with our results, which show that Rab5S43N does not inhibit gene induction by activin in Xenopus animal pole regions (Fig. 7G), the inhibition of endocytosis by RN-tre, dynaminK44A (a dominant-negative form of dynamin) and an antisense morpholino oligonucleotide directed against Rab5 does not prevent gene activation in response to Fgf8 (Scholpp and Brand, 2004). Our results differ, however, from those of Jullien and Gurdon, who report that dynaminK44E inhibits activin-induced induction of Xbra and eomesodermin in Xenopus blastomeres (Jullien and Gurdon, 2005). As discussed above, we do not yet understand the reason for this apparent discrepancy, which is under investigation.

Finally, we noted in the course of our experiments that Alexa488-activin occasionally accumulated at the site of membrane scission following cytokinesis (20-30% of cells; Fig. 1B; see Movie 1 in the supplementary material). A similar accumulation of transferrin has been suggested to occur as a result of the directed transport of recycling vesicles carrying receptor-bound ligand to the midbody region (Schweitzer et al., 2005). This may ensure the equal distribution of signalling complexes between daughter cells (Bokel et al., 2006). Cells lacking functional Rab11, a marker of recycling vesicles, fail to complete cytokinesis (Yu et al., 2007); a similar effect is observed following overexpression of Cherry-Rab11 (see Movie 1, left cell in the supplementary material).

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://dev.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/136/16/2803/DC1

Supplementary Material

We thank all present and former members of our laboratory, especially Elizabeth Callery and Kevin Dingwell, for their helpful comments. We are also grateful to Mike Gilchrist (Gurdon Institute) for discussion and to Marcos Gonzalez-Gaitan and Roger Tsien for cDNA constructs. This work is supported by the EU sixth framework project `EndoTrack' (FP6 Grant LSHG-CT-2006-019050), by a Wellcome Trust Programme Grant awarded to J.C.S., and by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), Portugal. A.I.H. is a student of the Gulbenkian PhD Program in Biomedicine, Portugal. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

References

- Agius, E., Oelgeschlager, M., Wessely, O., Kemp, C. and De Robertis, E. M. (2000). Endodermal Nodal-related signals and mesoderm induction in Xenopus. Development 127, 1173-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armes, N. A. and Smith, J. C. (1997). The ALK-2 and ALK-4 activin receptors transduce distinct mesoderm-inducing signals during early Xenopus development but do not co-operate to establish thresholds. Development 124, 3797-3804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenkaya, T. Y., Han, C., Yan, D., Opoka, R. J., Khodoun, M., Liu, H. and Lin, X. (2004). Drosophila Dpp morphogen movement is independent of dynamin-mediated endocytosis but regulated by the glypican members of heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cell 119, 231-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birsoy, B., Kofron, M., Schaible, K., Wylie, C. and Heasman, J. (2006). Vg 1 is an essential signaling molecule in Xenopus development. Development 133, 15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokel, C., Schwabedissen, A., Entchev, E., Renaud, O. and Gonzalez-Gaitan, M. (2006). Sara endosomes and the maintenance of Dpp signaling levels across mitosis. Science 314, 1135-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottger, G., Nagelkerken, B. and van der Sluijs, P. (1996). Rab4 and Rab7 define distinct nonoverlapping endosomal compartments. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 29191-29197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourillot, P. Y., Garrett, N. and Gurdon, J. B. (2002). A changing morphogen gradient is interpreted by continuous transduction flow. Development 129, 2167-2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. L., Hou, W. H., Liu, I. H., Hsiao, G., Huang, S. S. and Huang, J. S. (2009). Inhibitors of clathrin-dependent endocytosis enhance TGF{beta} signaling and responses. J. Cell Sci. 122, 1863-1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entchev, E. V., Schwabedissen, A. and Gonzalez-Gaitan, M. (2000). Gradient formation of the TGF-beta homolog Dpp. Cell 103, 981-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gaitan, M. and Jackle, H. (1999). The range of spalt-activating Dpp signalling is reduced in endocytosis-defective Drosophila wing discs. Mech. Dev. 87, 143-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, J. (2002). Morphogen gradients, positional information, and Xenopus: interplay of theory and experiment. Dev. Dyn. 225, 392-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, O. H. and Gurdon, J. B. (2002). Nuclear exclusion of Smad2 is a mechanism leading to loss of competence. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 519-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, S. A. and Smith, J. C. (2009). Visualisation and quantification of morphogen gradient formation in the zebrafish. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman, J. (2006). Patterning the early Xenopus embryo. Development 133, 1205-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiung, F., Ramirez-Weber, F. A., Iwaki, D. D. and Kornberg, T. B. (2005). Dependence of Drosophila wing imaginal disc cytonemes on Decapentaplegic. Nature 437, 560-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H., Milstein, M., Bliss, J. M., Thai, M., Malhotra, G., Huynh, L. C. and Colicelli, J. (2008). Integration of transforming growth factor beta and RAS signaling silences a RAB5 guanine nucleotide exchange factor and enhances growth factor-directed cell migration. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 1573-1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona, J. P., Lee, J. H., Robertson, C. P., Enga, K., Kapur, R. P. and Roelink, H. (2000). Receptor-mediated endocytosis of soluble and membrane-tethered Sonic hedgehog by Patched-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 12044-12049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C. M., Kuehn, M. R., Hogan, B. L., Smith, J. C. and Wright, C. V. (1995). Nodal-related signals induce axial mesoderm and dorsalize mesoderm during gastrulation. Development 121, 3651-3662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C. M., Armes, N. and Smith, J. C. (1996). Signalling by TGF-β family members: short-range effects of Xnr-2 and BMP-4 contrast with the long-range effects of activin. Curr. Biol. 6, 1468-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, E. M. and Melton, D. A. (1997). Xnr4: a Xenopus nodal-related gene expressed in the Spemann organizer. Dev. Biol. 184, 367-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jullien, J. and Gurdon, J. (2005). Morphogen gradient interpretation by a regulated trafficking step during ligand-receptor transduction. Genes Dev. 19, 2682-2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, T., Jullien, J. and Gurdon, J. B. (2006). Two-dimensional morphogen gradient in Xenopus: boundary formation and real-time transduction response. Dev. Dyn. 235, 3189-3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander, A. D. (2007). Morpheus unbound: reimagining the morphogen gradient. Cell 128, 245-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander, A. D., Nie, Q. and Wan, F. Y. (2002). Do morphogen gradients arise by diffusion? Dev. Cell 2, 785-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuit, T. and Cohen, S. M. (1998). Dpp receptor levels contribute to shaping the Dpp morphogen gradient in the Drosophila wing imaginal disc. Development 125, 4901-4907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z., Murray, J. T., Luo, W., Li, H., Wu, X., Xu, H., Backer, J. M. and Chen, Y. G. (2002). Transforming growth factor beta activates Smad2 in the absence of receptor endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29363-29368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey, M. W., Bielli, A., Cantalupo, G., Mora, S., Roberti, V., Santillo, M., Drummond, F. and Bucci, C. (2001). Rab4 affects both recycling and degradative endosomal trafficking. FEBS Lett. 495, 21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehrs, C., Steinbeisser, H. and De Robertis, E. M. (1994). Mesodermal patterning by a gradient of the vertebrate homeobox gene goosecoid. Science 263, 817-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop, P. D. and Faber, J. (1975). Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin). Amsterdam: North Holland.

- Ogata, S., Morokuma, J., Hayata, T., Kolle, G., Niehrs, C., Ueno, N. and Cho, K. W. (2007). TGF-beta signaling-mediated morphogenesis: modulation of cell adhesion via cadherin endocytosis. Genes Dev. 21, 1817-1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panopoulou, E., Gillooly, D. J., Wrana, J. L., Zerial, M., Stenmark, H., Murphy, C. and Fotsis, T. (2002). Early endosomal regulation of Smad-dependent signaling in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18046-18052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penheiter, S. G., Mitchell, H., Garamszegi, N., Edens, M., Dore, J. J., Jr and Leof, E. B. (2002). Internalization-dependent and -independent requirements for transforming growth factor beta receptor signaling via the Smad pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 4750-4759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piepenburg, O., Grimmer, D., Williams, P. H. and Smith, J. C. (2004). Activin redux: specification of mesodermal pattern in Xenopus by graded concentrations of endogenous activin B. Development 131, 4977-4986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan, C. E., Schnaper, H. W. and Poncelet, A. C. (2005). The role of internalization in transforming growth factor beta1-induced Smad2 association with Smad anchor for receptor activation (SARA) and Smad2-dependent signaling in human mesangial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8300-8308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saka, Y. and Smith, J. C. (2007). A mechanism for the sharp transition of morphogen gradient interpretation in Xenopus. BMC Dev. Biol. 7, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saka, Y., Hagemann, A. I., Piepenburg, O. and Smith, J. C. (2007). Nuclear accumulation of Smad complexes occurs only after the midblastula transition in Xenopus. Development 134, 4209-4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saka, Y., Hagemann, A. I. and Smith, J. C. (2008). Visualizing protein interactions by bimolecular fluorescence complementation in Xenopus. Methods 45, 192-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saksena, S., Sun, J., Chu, T. and Emr, S. D. (2007). ESCRTing proteins in the endocytic pathway. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 561-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholpp, S. and Brand, M. (2004). Endocytosis controls spreading and effective signaling range of Fgf8 protein. Curr. Biol. 14, 1834-1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, J. K., Burke, E. E., Goodson, H. V. and D'Souza-Schorey, C. (2005). Endocytosis resumes during late mitosis and is required for cytokinesis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 41628-41635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack, J. M. (1984). Regional biosynthetic markers in the early amphibian embryo. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 80, 289-319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. C. (1995). Mesoderm-inducing factors and mesodermal patterning. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 7, 856-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnichsen, B., De Renzis, S., Nielsen, E., Rietdorf, J. and Zerial, M. (2000). Distinct membrane domains on endosomes in the recycling pathway visualized by multicolor imaging of Rab4, Rab5, and Rab11. J. Cell Biol. 149, 901-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B. I., Bush, S. M., Collins-Racie, L. A., LaVallie, E. R., DiBlasio-Smith, E. A., Wolfman, N. M., McCoy, J. M. and Sive, H. L. (1999). derriere: a TGF-beta family member required for posterior development in Xenopus. Development 126, 1467-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada, M., O'Reilly, M.-A. J. and Smith, J. C. (1997). Analysis of competence and of Brachyury autoinduction by use of hormone-inducible Xbra. Development 124, 2225-2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, S., Yokota, C., Takano, K., Tanegashima, K., Onuma, Y., Goto, J. and Asashima, M. (2000). Two novel nodal-related genes initiate early inductive events in Xenopus Nieuwkoop center. Development 127, 5319-5329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, R. J., Sun, B. I., Sive, H. L. and Smith, J. C. (2002). Direct and indirect regulation of derriere, a Xenopus mesoderm-inducing factor, by VegT. Development 129, 4867-4876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P. H., Hagemann, A., Gonzalez-Gaitan, M. and Smith, J. C. (2004). Visualizing long-range movement of the morphogen Xnr2 in the Xenopus embryo. Curr. Biol. 14, 1916-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R. L. and Urbe, S. (2007). The emerging shape of the ESCRT machinery. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 355-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M. Y. and Hill, C. S. (2009). Tgf-beta superfamily signaling in embryonic development and homeostasis. Dev. Cell 16, 329-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X., Prekeris, R. and Gould, G. W. (2007). Role of endosomal Rab GTPases in cytokinesis. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 86, 25-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerial, M. and McBride, H. (2001). Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 107-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y., Scolavino, S., Funderburk, S. F., Ficociello, L. F., Zhang, X. and Klibanski, A. (2004). Receptor internalization-independent activation of Smad2 in activin signaling. Mol. Endocrinol. 18, 1818-1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaagstra, J. C., El-Alfy, M. and O'Connor-McCourt, M. D. (2001). Transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta 1 internalization: modulation by ligand interaction with TGF-beta receptors types I and II and a mechanism that is distinct from clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27237-27245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.