Abstract

Background

We conducted secondary data analyses of a clinical trial (HIVNET 024) to assess risk factors for late postnatal transmission (LPT) of HIV-1 through breastfeeding.

Methods

Data regarding live born, singleton infants of HIV-1-infected mothers were analyzed. The timing of HIV-1 transmission through 12 months after birth was defined as: in utero (positive HIV-1 RNA results at birth), perinatal/early postnatal (negative results at birth, positive at 4–6 week visit), or LPT (negative results through the 4–6 week visit, but positive assays thereafter through the 12 month visit). HIV-1-uninfected infants were those with negative HIV-1 enzyme immunoassay results at 12 months of age, or infants with negative HIV-1 RNA results throughout follow-up.

Results

Of 2292 HIV-1-infected enrolled women, 2052 mother/infant pairs met inclusion criteria. Of 1979 infants with HIV-1 tests, 404 were HIV-1-infected, and 382 had known timing of infection (LPT represented 22% of transmissions). Further analyses of LPT included infants who were breastfeeding at the 4–6 week visit (with negative HIV-1 results at that visit) revealed 6.9% of 1317 infants acquired HIV-1 infection through LPT by 12 months of age. More advanced maternal HIV-1 disease at enrollment (lower CD4+ counts, higher plasma viral loads) were the factors associated with LPT in adjusted analyses.

Conclusions

In this breastfeeding population, 6.9% of infants uninfected at 6 weeks of age acquired HIV-1 infection by 12 months. Making interventions to decrease the risk of LPT of HIV-1 available and continuing research regarding the mechanisms of LPT (so as to develop improved interventions to reduce such transmission) remain essential.

Keywords: Breast feeding, mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1, risk factors, Sub-Saharan Africa

INTRODUCTION

The risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 continues to be high in resource-poor settings where efficacious interventions to prevent transmission such as antiretroviral prophylaxis, cesarean section before labor and ruptured membranes, and complete avoidance of breastfeeding (1) are not universally available. In such settings, and in the absence of any intervention to prevent transmission, the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 is approximately 15%–42% (2).

In sub-Saharan Africa, where prolonged breast feeding is customary, breast milk transmission represents an important mechanism of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. In an individual patient data meta-analysis of more than three thousand breastfeeding infants of HIV-1-infected women from sub-Saharan Africa, rates of transmission of HIV-1 through breast milk were estimated with relatively high precision (3); the cumulative probability of late postnatal transmission at 18 months was 9.3% and the overall risk of late postnatal transmission was 8.9 transmissions/100 child-years of breastfeeding.

We conducted secondary data analyses of a clinical trial (HIVNET 024) to assess risk factors for breast milk transmission of HIV-1 among mothers and infants enrolled in the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HIVNET) Protocol 024, a clinical trial of antibiotics to prevent chorioamnionitis-associated perinatal HIV-1 transmission and preterm birth conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (4).

METHODS

HIVNET 024 Trial

The HIVNET 024 trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase III trial conducted at four sites in three African countries: Blantyre and Lilongwe, Malawi, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; and Lusaka, Zambia. The design and results of the trial have been described in detail previously (4). The primary objectives of the trial were to evaluate the efficacy of antibiotics to reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 and preterm birth. In the trial, eligible women were randomized to receive either antibiotics (metronidazole with erythromycin antenatally and metronidazole with ampicillin intrapartum) or placebo. All HIV-1-infected women participating in HIVNET 024 and their infants received NVP according to the HIVNET 012 regimen for prevention of MTCT of HIV (5). Infant study visits were conducted at birth (within the first 48 hours), at 4–6 weeks, and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. Information also was collected on breastfeeding and maternal health at these visits. Although each clinical site provided counseling regarding the risks and benefits of breastfeeding, replacement feeding or other interventions related to prevention of breastfeeding transmission of HIV-1 infection were not implemented as part of the trial. Antiretroviral treatment for mothers and children was not available at any of the clinical sites at the time the trial was conducted. HIVNET 024 was approved by each of the in-country and U.S.-associated Institutional Review Boards or Ethical Committees.

Study Population and Definitions for This Analysis

Data regarding HIV-1-infected women and their live born infants (singletons or, if a multiple gestation, first born infants) who were enrolled in the HIVNET 024 trial were analyzed. Infants with positive HIV-1 RNA assays at birth were considered to have acquired HIV-1 infection through in utero transmission. Those with a first positive assay at the six week study visit were considered to have acquired HIV-1 infection through perinatal/early postnatal transmission. Infants with negative HIV-1 RNA assay results at birth and at 4–6 weeks of age, but who had positive HIV-1 RNA test results thereafter through the 12 month visit, were considered to have acquired HIV-1 infection during the late postnatal period; these infants were considered to represent cases of breast milk transmission of HIV-1. In analyses of late postnatal transmission of HIV-1, the study population was restricted to infants who were breastfeeding at the time of the six week visit, with negative HIV-1 RNA assay results at that visit. HIV-1-uninfected infants were those with negative enzyme immunoassay (EIA) results at 12 months of age, or infants with negative HIV-1 RNA assay results throughout follow-up.

Laboratory Procedures

At baseline, maternal blood was collected for a complete blood count (CBC), CD4+ cell counts, and plasma viral load assays. The CBC and CD4 tests were performed locally using HIVNET Central Laboratory (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore)-approved site-specific procedures. A cervical swab was also obtained at baseline for HIV-1 RNA testing. All maternal plasma and cervical swabs were tested for HIV-1 RNA using the Roche Amplicor Monitor RNA assay, version 1.5 (Branchburg, NJ) at the reference laboratory at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. HIV-1 diagnostic testing of women was performed according to site-specific procedures including either a rapid test or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay/Western blot tests. All initially positive HIV-1 test results were confirmed with an additional test on site.

At infant study visits, blood was collected to prepare a dried blood spot (DBS). Nucleic acids were extracted from all of the DBS using the silica bead isolation procedure (6) (bioMerieux, Durham, NC). HIV-1 RNA was detected using a NASBA technology (bioMerieux NucliSens QL) for the Malawi and Zambia sites while the Roche Amplicor Monitor version 1.5 was used for samples for Tanzania site in a reference laboratory (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA). Positive results were confirmed by retesting the same DBS or a subsequent one. DBS specimens from 10% of infants considered to be HIV-1-infected and an equal number who never tested positive were re-tested in the HIVNET Central Laboratory. The laboratory personnel were not aware of infant HIV-1 infection status or study arm.

The HIVNET Central Laboratory reviewed and certified all local laboratories before the initiation of the trial. On a periodic basis throughout the trial, the Central Laboratory verified virologic, serologic, hematologic, immunologic, and biochemical tests based on proficiency panels provided by the College of American Pathology (CAP) and United Kingdom National External Quality Assessment Service (UKNEQAS).

Statistical analysis

In time-to-event regression analyses of time to late postnatal transmission of HIV-1 (through 12 months), the event-time outcome of an infected infant was determined by the mid-point between the last negative and the first positive HIV-1 RNA assay results (subsequent to the six week visit and at or before the 12 month visit). An event-time was considered censored at the date of the last negative HIV-1 RNA test result if the infant did not test positive at or before the 12 month visit. Kaplan-Meier estimates of the proportion of infants breastfeeding at different time points during infancy, infant survival, late postnatal transmission of HIV-1, and maternal survival were computed for each site. Pairwise comparisons of the Kaplan-Meier estimates for the sites were performed, and p-values were adjusted by the Bonferroni method. Cox proportional hazards modeling (7) was performed to identify factors associated with late postnatal transmission of HIV-1. All Cox models were stratified by site. All variables from the univariate analyses were initially included in multivariate modeling. A backward stepwise model-fitting procedure using a 0.25 p-value cut-off for variable selection was initially applied to arrive at an intermediate model. The final model was attained by applying a p-value cut-off of 0.05 to the intermediate model. All statistical calculation and analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.3 on SunOS 5.9 platform.

RESULTS

Derivation of the Study Population, Transmission Rates

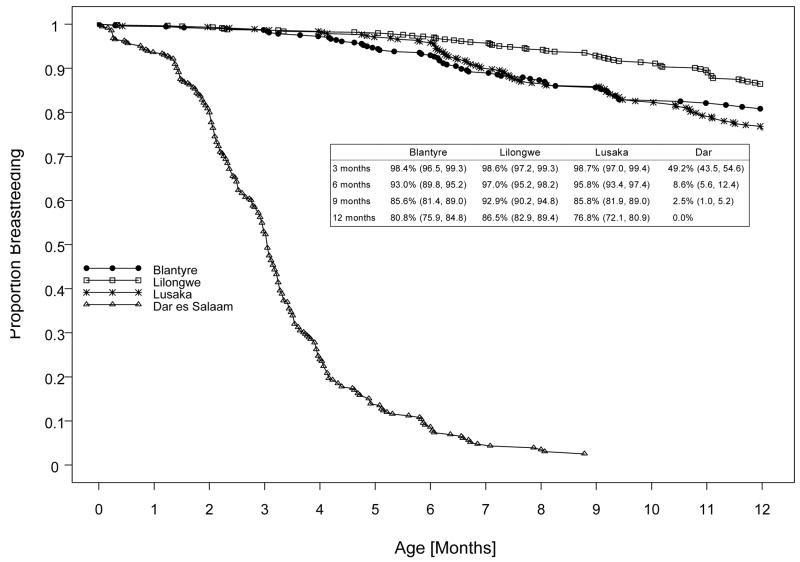

Of the 2659 women enrolled in HIVNET 024, 2292 were HIV-1-infected. Of these, 2052 delivered live born infants, including 2026 singletons and 26 first-born twins. Overall, 90% of infants were still being breastfed at three months of age, with this proportion decreasing over time until only 68% of infants were still breastfeeding at 12 months of age (Figure 1). However, the duration of breastfeeding varied significantly by site, with duration of breastfeeding at the Dar es Salaam site being quite shorter (median duration: three months) than that at the other sites. At the Dar es Salaam site, only 2.5% of women were still breastfeeding their infants by nine months. In contrast, at the other three sites, more than 98% of infants were still being breastfed at three months of age and the majority (77–87%) were still breastfeeding at 12 months of age.

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier curves depicting the proportion of infants who were breastfeeding at different time points during the first 12 months of life, according to clinical site.

Of the 2052 live born infants, 73 had no HIV-1 diagnostic test results through the end of study follow-up. Of the remaining 1979 infants, 404 were HIV-1-infected, 1573 were HIV-1-uninfected, and two were of indeterminate HIV-1 infection status. Therefore, the overall HIV-1 transmission rate was 20.4% (95% confidence interval: 18.7%, 22.2%).

Of 404 HIV-1-infected infants, 22 had unknown timing of infection. Of the remaining 382 HIV-1-infected infants, 153 had presumed in utero transmission (positive HIV-1 diagnostic assay results at birth), 128 had presumed perinatal/early postnatal infection (negative at birth, positive at 6 weeks), 17 had either in utero or perinatal/early postnatal infection (positive at six weeks, no previous sample), and 84 had presumed late postnatal transmission (negative at 6 weeks, positive later). Therefore, 78% (95%CI: 73.9%, 82.2%) of the observed 382 infections were presumed to have occurred in utero or during the perinatal/early postnatal period, while 22% (95%CI: 17.8%, 26.1%) of the observed HIV-1 infections were presumed to have occurred during the late postnatal period.

Of 1657 infants with known HIV-1 infection status and negative HIV-1 diagnostic assays at six weeks of age, 270 had no HIV-1 diagnostic test results after age six weeks, and 70 did not breastfeed beyond six weeks of age. Therefore, the analysis cohort for late postnatal transmission of HIV-1 in a breastfeeding population comprised 1317 infants with negative HIV-1 diagnostic assay results at six weeks of age, who had subsequent HIV-1 diagnostic testing performed and who continued to breastfeed after six weeks of age. Of these 1317 infants, 84 became HIV-1-infected after six weeks but before 12 months of age (62 infants had two positive HIV-1 diagnostic assays, and 22 infants had one positive assay; of the 22 infants with one positive assay, 10 died before another assay could be performed). By 12 months, the late postnatal transmission rate (estimated from the Kaplan-Meier survival curve) was 6.9% [95% CI: 5.6%, 8.5%] (Table 1). Of the 1233 HIV-1-uninfected infants, 796 had a negative EIA assay at 12 months of age and 437 had a negative HIV-1 RNA assay results throughout follow-up. There were statistically significant differences in the timing of late postnatal transmission between the Lilongwe and Lusaka sites (p=0.02). At the Blantyre site, samples taken at three, six, and nine months of age were lost for the 16 infants with positive HIV-1 RNA assay results at 12 months of age. Because HIV-1 RNA assay results were not available at these earlier time points, the estimated timing of HIV-1 infections was artificially early for Blantyre.

Table 1.

Proportion of infants with HIV-1 infection at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months

| Blantyre | Lilongwe | Lusaka | Dar | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 0.4% (0.1, 2.5) | 0.2% (0.0, 1.6) | 3.5% (2.1, 6.0) | 3.3% (1.6, | 1.5% (0.9, 2.3) |

| 6 months | 1.5% (0.5, 3.8) | 3.1% (1.9, 5.3) | 7.6% (5.3, | 4.3% (2.2, | 4.1% (3.2, 5.4) |

| 9 months | 6.7% (4.3, | 4.4% (2.8, 6.7) | 8.5% (6.0, | 6.1% (4.9, 7.5) | |

| 12 months | 4.9% (3.2, 7.4) | 10.5% (7.7, | 6.9% (5.6, 8.5) |

Characteristics of the Study Population (N = 1317 infants)

Of the 1317 infants in the study population, 52 (4.0%) died during the late postnatal period and 17 (1.3%) of their mothers died during this period. Maternal survival did not vary significantly across the sites. However, the infant survival curves differed according to site (Blantyre versus Lusaka sites: p value = 0.03; Blantyre versus Dar es Salaam site: p value < 0.01). Other characteristics of the study population, overall and according to site, are shown in Table 2 (on line only). At enrollment, almost 16% of women had CD4+ counts < 200 cells/mm3, and more than 60% had plasma viral loads ≥ 10,000 copies/mL. Fewer than five percent of women had breast pathology (e.g., mastitis) during follow-up. Similarly, only approximately three percent of infants were diagnosed with oral candidiasis, and none had stomatitis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study population, overall and by site (N = 1317 mother-infant pairs)

| Characteristic | Blantyre N = 281 |

Lilongwe N = 450 |

Lusaka N = 371 |

Dar es Salaam N = 215 |

Overall N = 1317 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Maternal | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| At Enrollment | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Age (years) | ≤ 20 | 59 (21.0) | 55 (12.2) | 75 (20.2) | 32 (14.9) | 221 (16.8) |

| 21–29 | 170 (60.5) | 306 (68.0) | 230 (62.0) | 134 (62.3) | 840 (63.8) | |

| ≥ 30 | 52 (18.5) | 89 (19.8) | 66 (17.8) | 49 (22.8) | 256 (19.4) | |

| Education (years) | ≤ 3 | 59 (21.0) | 126 (28.0) | 48 (12.9) | 26 (12.1) | 259 (19.7) |

| 4–9 | 139 (49.5) | 241 (53.6) | 266 (71.7) | 172 (80.0) | 818 (62.1) | |

| ≥ 10 | 83 (29.5) | 83 (18.4) | 56 (15.1) | 17 (7.9) | 239 (18.1) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Marital Status | Married/Living with Partner | 262 (93.2) | 434 (96.4) | 329 (88.7) | 178 (82.8) | 1203 (91.3) |

| Other | 19 (6.8) | 16 (3.6) | 42 (11.3) | 37 (17.2) | 114 (8.7) | |

| Electricity in the home | Yes | 114 (40.6) | 67 (14.9) | 169 (45.6) | 159 (74.0) | 509 (38.6) |

| No | 167 (59.4) | 383 (85.1) | 202 (54.4) | 56 (26.0) | 808 (61.4) | |

| Running water in the home | Yes | 115 (40.9) | 132 (29.3) | 150 (40.4) | 144 (67.0) | 541 (41.1) |

| No | 166 (59.1) | 318 (70.7) | 221 (59.6) | 71 (33.0) | 776 (58.9) | |

| CD4+ count (cells/mm3) | < 200 | 47 (16.7) | 72 (16.0) | 54 (14.6) | 34 (15.8) | 207 (15.7) |

| 200–499 | 85 (30.2) | 226 (50.2) | 218 (58.8) | 119 (55.3) | 648 (49.2) | |

| ≥ 500 | 37 (13.2) | 141 (31.3) | 99 (26.7) | 50 (23.3) | 327 (24.8) | |

| Missing | 112 (39.9) | 11 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (5.6) | 135 (10.3) | |

| Plasma viral load (copies/mL) | < 1,000 | 18 (6.4) | 33 (7.3) | 32 (8.6) | 29 (13.5) | 112 (8.5) |

| ≥ 1000, < 10,000 | 54 (19.2) | 107 (23.8) | 88 (23.7) | 83 (38.6) | 332 (25.2) | |

| ≥ 10,000, < 50,000 | 105 (37.4) | 148 (32.9) | 145 (39.1) | 78 (36.3) | 476 (36.1) | |

| ≥ 50,000 | 81 (28.8) | 153 (34.0) | 73 (19.7) | 25 (11.6) | 332 (25.2) | |

| Missing | 23 (8.2) | 9 (2.0) | 33 (8.9) | 0 (0.0) | 65 (4.9) | |

| Cervicovaginal fluid viral load(copies/mL) | < 1,000 | 42 (14.9) | 176 (39.1) | 88 (23.7) | 98 (45.6) | 404 (30.7) |

| ≥ 1000, < 10,000 | 64 (22.8) | 169 (37.6) | 109 (29.4) | 54 (25.1) | 396 (30.1) | |

| ≥ 10,000, < 50,000 | 44 (15.7) | 64 (14.2) | 81 (21.8) | 39 (18.1) | 228 (17.3) | |

| ≥ 50,000 | 19 (6.8) | 17 (3.8) | 28 (7.5) | 12 (5.6) | 76 (5.8) | |

| Missing | 112 (39.9) | 24 (5.3) | 65 (17.5) | 12 (5.6) | 213 (16.2) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

|

| ||||||

| During Follow-up | ||||||

| CD4+ count at 36 weeks (cells/mm3) | < 200 | 33 (11.7) | 67 (14.9) | 38 (10.2) | 18 (8.4) | 156 (11.8) |

| 200–499 | 84 (29.9) | 188 (41.8) | 151 (40.7) | 88 (40.9) | 511 (38.8) | |

| ≥ 500 | 26 (9.3) | 118 (26.2) | 93 (25.1) | 61 (28.4) | 298 (22.6) | |

| Missing | 138 (49.1) | 77 (17.1) | 89 (24.0) | 48 (22.3) | 352 (26.7) | |

| Receipt of NVP prophylaxis | Yes | 273 (97.2) | 439 (97.6) | 361 (97.3) | 211 (98.1) | 1284 (97.5) |

| No | 8 (2.8) | 11 (2.4) | 10 (2.7) | 4 (1.9) | 33 (2.5) | |

| Mastitis at 4–6 weeks postpartum | Yes | 8 (2.8) | 7 (1.6) | 9 (2.4) | 2 (0.9) | 26 (2.0) |

| No | 273 (97.2) | 443 (98.4) | 362 (97.6) | 213 (99.1) | 1291 (98.0) | |

| Cracked nipples at 4–6 weeks postpartum | Yes | 3 (1.1) | 5 (1.1) | 7 (1.9) | 2 (0.9) | 17 (1.3) |

| No | 278 (98.9) | 445 (98.9) | 364 (98.1) | 213 (99.1) | 1300 (98.7) | |

| Infant | ||||||

| At Birth | ||||||

| Gestational age < 37 weeks (by fundal height) | Yes | 76 (27.0) | 67 (14.9) | 96 (25.9) | 29 (13.5) | 268 (20.3) |

| No | 205 (73.0) | 383 (85.1) | 275 (74.1) | 186 (86.5) | 1049 (79.7) | |

| Birth weight < 2500 grams | Yes | 24 (8.5) | 36 (8.0) | 40 (10.8) | 17 (7.9) | 117 (8.9) |

| No | 247 (87.9) | 391 (86.9) | 319 (86.0) | 197 (91.6) | 1154 (87.6) | |

| Missing | 10 (3.6) | 23 (5.1) | 12 (3.2) | 1 (0.5) | 46 (3.5) | |

| Gender | Male | 146 (52.0) | 241 (53.6) | 196 (52.8) | 98 (45.6) | 681 (51.7) |

| Female | 135 (48.0) | 209 (46.4) | 175 (47.2) | 117 (54.4) | 636 (48.3) | |

| Receipt of NVP prophylaxis | Yes | 266 (94.7) | 428 (95.1) | 348 (93.8) | 212 (98.6) | 1254 (95.2) |

| No | 15 (5.3) | 22 (4.9) | 22 (5.9) | 3 (1.4) | 62 (4.7) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| During Follow-up | ||||||

| Oral candidiasis at 4–6 weeks of age | Yes | 2 (0.7) | 6 (1.3) | 9 (2.4) | 12 (5.6) | 29 (2.2) |

| No | 279 (99.3) | 444 (98.7) | 362 (97.6) | 203 (94.4) | 1288 (97.8) | |

| Stomatitis at 4–6 weeks of age | Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No | 281 (100.0) | 450 (100.0) | 371 (100.0) | 215 (100.0) | 1317 (100.0) | |

| Diarrhea at 4–6 weeks of age | Yes | 4 (1.4) | 2 (0.4) | 4 (1.1) | 3 (1.4) | 13 (1.0) |

| No | 277 (98.6) | 448 (99.6) | 367 (98.9) | 212 (98.6) | 1304 (99.0) | |

Factors Associated with Late Postnatal Transmission

All of the variables included in Table 2 (except for infant stomatitis, of which no cases were observed in the study population) were evaluated for associations with late postnatal transmission (Table 3). Lower maternal CD4+ counts (at enrollment and at 36 weeks gestation) and higher viral loads (plasma and cervicovaginal fluid at enrollment) were most strongly associated with late postnatal transmission. Multivariate modeling included all variables in Table 3, except for maternal CD4+ count at 36 weeks (since data regarding this variable were missing for a large proportion of women, and since this variable was highly correlated with maternal CD4+ count at enrollment). Factors associated with late postnatal transmission in the final multivariate model were lower maternal CD4+ counts and higher maternal plasma viral loads at enrollment (Table 4).

Table 3.

Factors associated with late postnatal transmission of HIV-1 (N = 1317 infants) – univariate analyses

| Infant HIV-1 infection status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Infected (N = 84) |

Uninfected (N = 1233) |

Unadjusted * HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Maternal | ||||||

| At Enrollment | ||||||

| Age (years) | ≤20 | 15 (6.8) | 206 (93.2) | 1.05 | (0.59, 1.87) | 0.87 |

| 21–29 | 53 (6.3) | 787 (93.7) | 1.00 | ---------------- | ||

| ≥ 30 | 16 (6.3) | 240 (93.8) | 0.99 | (0.57, 1.73) | 0.98 | |

| Education (years) | ≤ 3 | 13 (5.0) | 246 (95.0) | 0.75 | (0.41, 1.40) | 0.37 |

| 4–9 | 56 (6.8) | 762 (93.2) | 1.00 | ---------------- | ||

| ≥ 10 | 15 (6.3) | 224 (93.7) | 0.94 | (0.52, 1.69) | 0.84 | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | ||||

| Marital Status | Married/Living with Partner | 74 (6.2) | 1129 (93.8) | 0.71 | (0.36, 1.39) | 0.32 |

| Other | 10 (8.8) | 104 (91.2) | 1.00 | ---------------- | ||

| Electricity in the home | Yes | 33 (6.5) | 476 (93.5) | 0.95 | (0.60, 1.52) | 0.84 |

| No | 51 (6.3) | 757 (93.7) | 1.00 | ---------------- | ||

| Running water in the home | Yes | 37 (6.8) | 504 (93.2) | 1.13 | (0.73, 1.76) | 0.58 |

| No | 47 (6.1) | 729 (93.9) | 1.00 | ---------------- | ||

| CD4+ count (cells/mm3) | < 200 | 29 (14.0) | 178 (86.0) | 8.92 | (3.69, 21.58) | <.0001 |

| 200–499 | 43 (6.6) | 605 (93.4) | 3.58 | (1.52, 8.43) | 0.0034 | |

| ≥ 500 | 6 (1.8) | 321 (98.2) | 1.00 | ---------------- | ||

| Missing | 6 (4.4) | 129 (95.6) | ||||

| Plasma viral load (copies/mL) | < 10,000 | 6 (1.4) | 438 (98.6) | 1.00 | ---------------- | |

| ≥ 10,000, < 50,000 | 31 (6.5) | 445 (93.5) | 5.04 | (2.09, 12.11) | 0.0003 | |

| ≥ 50,000 | 42 (12.7) | 290 (87.3) | 10.37 | (4.35, 24.68) | <.0001 | |

| Missing | 5 (7.7) | 60 (92.3) | ||||

| Cervicovaginal fluid viral load(copies/mL) | < 1000 | 7 (1.7) | 397 (98.3) | 1.00 | ---------------- | |

| ≥ 1000, < 10,000 | 26 (6.6) | 370 (93.4) | 3.97 | (1.71, 9.21) | 0.0013 | |

| ≥ 10,000, < 50,000 | 24 (10.5) | 204 (89.5) | 5.72 | (2.43, 13.46) | <.0001 | |

| ≥ 50,000 | 7 (9.2) | 69 (90.8) | 5.64 | (1.90, 16.79) | 0.0019 | |

| Missing | 20 (9.4) | 193 (90.6) | ||||

| During Follow-up | ||||||

| CD4+ count at 36 weeks (cells/mm3) | < 200 | 19 (12.2) | 137 (87.8) | 10.20 | (3.43, 30.36) | <.0001 |

| 200–499 | 35 (6.8) | 476 (93.2) | 5.30 | (1.88, 14.94) | 0.0016 | |

| ≥ 500 | 4 (1.3) | 294 (98.7) | 1.00 | ---------------- | ||

| Missing | 26 (7.4) | 326 (92.6) | ||||

| Receipt of NVP prophylaxis | Yes | 84 (6.5) | 1200 (93.5) | |||

| No | 0 (0.0) | 33 (100.0) | ||||

| Mastitis at 4–6 weeks postpartum | Yes | 1 (3.8) | 25 (96.2) | 0.52 | (0.07, 3.74) | 0.52 |

| No | 83 (6.4) | 1208 (93.6) | 1.00 | ---------------- | ||

| Cracked nipples at 4–6 weeks postpartum | Yes | 1 (5.9) | 16 (94.1) | 0.95 | (0.13, 6.80) | 0.96 |

| No | 83 (6.4) | 1217 (93.6) | 1.00 | ---------------- | ||

| Infant | ||||||

| At Birth | ||||||

| Gestational age < 37 weeks (by fundal height) | Yes | 24 (9.0) | 244 (91.0) | 0.68 | (0.42, 1.10) | 0.12 |

| No | 60 (5.7) | 989 (94.3) | 1.00 | ---------------- | ||

| Birth weight < 2500 grams | Yes | 8 (6.8) | 109 (93.2) | 0.96 | (0.46, 1.98) | 0.90 |

| No | 74 (6.4) | 1080 (93.6) | 1.00 | ---------------- | ||

| Missing | 2 (4.3) | 44 (95.7) | ||||

| Gender | Male | 47 (6.9) | 634 (93.1) | 1.18 | (0.76, 1.81) | 0.46 |

| Female | 37 (5.8) | 599 (94.2) | 1.00 | ---------------- | ||

| Receipt of NVP prophylaxis | Yes | 80 (6.4) | 1174 (93.6) | 0.99 | (0.36, 2.71) | 0.99 |

| No | 4 (6.5) | 58 (93.5) | ||||

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | ||||

| During Follow-up | ||||||

| Oral candidiasis at 4–6 weeks of age | Yes | 2 (6.9) | 27 (93.1) | 1.16 | (0.28, 4.76) | 0.83 |

| No | 82 (6.4) | 1206 (93.6) | ---------------- | |||

| Diarrhea at 4–6 weeks of age | Yes | 0 (0.0) | 13 (100.0) | |||

| No | 84 (6.4) | 1220 (93.6) | ||||

All univariate models were stratified by site.

Table 4.

Final Multivariate Model – Factors Associated with Late Postnatal Transmission of HIV-1*

| Characteristic | Category | Hazard Ratio (95%CI) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal CD4 count at enrollment(cells/mm3) | < 200 | 4.82 (1.96, 11.88) | 0.0006 |

| 200–499 | 2.17 (0.91, 5.18) | 0.0824 | |

| ≥ 500 | 1.00 | ||

| Maternal plasma viral load at enrollment (copies/mL) | < 10,000 | 1.00 | |

| ≥ 10,000, <50,000 | 4.34 (1.66, 11.36) | 0.0028 | |

| ≥ 50,000 | 8.85 (3.40, 23.03) | <.0001 |

Model stratified by site.

DISCUSSION

Among this large population of HIV-1-infected women and their infants in three sub-Saharan African countries, almost all of whom received perinatal transmission prophylaxis with nevirapine, the overall transmission rate through 12 months after birth was 20.4%. Among those HIV-1-infected infants with known timing of infection (382/404), an estimated 22% of infections occurred during the late postnatal period. Overall, 6.9% of infants with negative HIV-1 diagnostic assay results at 6 weeks of age acquired HIV-1 infection by 12 months of age. Lower maternal CD4+ cell counts and higher maternal plasma HIV-1 RNA concentrations were independently associated with an increased risk of late postnatal transmission of HIV-1.

Our estimates of the proportion of HIV-1 infections occurring during the late postnatal period and of the cumulative probability of late postnatal transmission of HIV-1 by 12 months of age are quite consistent with the results of the very large individual patient data meta-analysis of data from clinical trials conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (3). Although previously identified as risk factors for mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 (3, 8–9), maternal age, parity, infant birth weight, and infant gender were not independent risk factors for breastfeeding transmission in our analyses. Our results confirm previous reports suggesting that more advanced maternal disease stage, as manifested by low CD4+ absolute lymphocyte counts, is an independent risk factor for postnatal transmission of HIV-1 (10–13). The HIV-1 RNA concentration in cervicovaginal fluid was not a significant risk factor for transmission in this analysis. However, our results confirm that a higher maternal plasma viral load, previously associated with in utero or intrapartum transmission of HIV-1 (10, 13–15) as well as breastfeeding transmission of HIV-1 (11, 15–16), is an independent risk factor for postnatal transmission of HIV-1 through breastfeeding.

Limitations of our analysis should be considered. First, the participating sites in the HIVNET 024 clinical trial were all located in urban areas, while most of the population of sub-Saharan Africa lives in rural areas where breastfeeding continues for a longer period. Thus, the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 due to late postnatal transmission in this analysis may represent an underestimate. Although it is of interest because of previously reported associations with transmission through breastfeeding, type of feeding (exclusive breastfeeding vs. mixed breastfeeding) could not be examined since such information was not collected systematically as part of the HIVNET 024 clinical trial.

The implications of the results of this analysis are two-fold. First, because the risk of transmission through breastfeeding is increased among women with more advanced HIV-1 disease (as manifested by lower CD4+ cell counts and higher plasma HIV-1 RNA concentrations), efforts to increase access to antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1-infected women, including pregnant women, should be supported. Second, the substantial proportion of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 due to breastfeeding serves to emphasize the importance of preventing such transmission. Interventions to reduce the risk of transmission of HIV-1 through breast milk are being developed and evaluated (17). For example, clinical trials regarding antiretroviral prophylaxis administered to HIV-1-infected mothers and/or their infants during breastfeeding are underway. Making efficacious and effective interventions to prevent breast milk transmission of HIV-1 available, and conducting research regarding the mechanisms of breast milk transmission, are essential to reduce the risk of transmission of HIV-1 through breastfeeding.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the mothers and children who participated in this study. We are also grateful to the entire study team at each site for their dedication and excellent collaboration. Our thanks are extended to institutions that contributed to the conduct of this study in each country.

We acknowledge the support for this work by the HIV Network for Prevention Trials (HIVNET) and sponsorship from the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, through contract N01-AI-35173 with Family Health International; contract N01-AI-45200 with Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; and subcontract N01-AI-35173-117/412 with Johns Hopkins University. In addition, this work was supported by HIVNET and sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, and Office of AIDS Research, of the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI-50410), Harvard University (U01-AI-48006), Johns Hopkins University (U01-AI-48005), and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (U01-AI-47972). Nevirapine (Viramune®) for the study was provided by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The conclusions and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agencies and participating institutions.

APPENDIX

HIVNET 024 Team

Protocol Co-Chairs: Taha E. Taha, MD, PhD (Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health); Robert Goldenberg, MD (University of Alabama at Birmingham); In-Country Co-Chairs/Investigators of Record: Newton Kumwenda, PhD, George Kafulafula, MBBS, FCOG (Blantyre, Malawi); Francis Martinson, MD, PhD (Lilongwe, Malawi); Gernard Msamanga, MD, ScD (Dar es Salaam, Tanzania); Moses Sinkala, MD, MPH (Lusaka, Zambia); US Co-Chairs: Irving Hoffman, PA, MPH (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill); Wafaie Fawzi, MD, DrPH (Harvard School of Public Health ); In-Country Investigators, Consultants and Key Site Personnel: Robin Broadhead, MBBS, FRCP, George Liomba, MBBS, FRCPath, Johnstone Kumwenda, MBChB, MRCP, Tsedal Mebrahtu, ScM, Pauline Katunda, MHS, Maysoon Dahab, MHS (Blantyre, Malawi); Peter Kazembe, MBChB, David Chilongozi CO, MPH, Charles Chasela BSc, MSc, George Joaki, MD, Willard Dzinyemba, Sam Kamanga (Lilongwe, Malawi); Elgius Lyamuya, MD, PhD, Charles Kilewo, MD, MMed, Karim Manji, MD, MMed, Sylvia Kaaya, MD, MS, Said Aboud, MD, MMed, Muhsin Sheriff MD, MPH, Elmar Saathoff, PhD, Priya Satow, MPH, Illuminata Ballonzi, SRN, Gretchen Antelman, ScD, Edgar Basheka, BPharm (Dar es Salaam, Tanzania); Victor Mudenda, MD, Christine Kaseba, MD, Maureen Njobvu, MD, Makungu Kabaso, MD, Muzala Kapina, MD, Anthony Yeta, MD, Seraphine Kaminsa, MD, MPH, Constantine Malama, MD, Dara Potter, MBA, Maclean Ukwimi, RN, Alison Taylor, BSc, Patrick Chipaila, MSc, Bernice Mwale, BPharm (Lusaka, Zambia); US Investigators, Consultants and Key Site Personnel: Priya Joshi, BS, Ada Cachafeiro, BS, Shermalyn Greene, PhD, Marker Turner, BS, Melissa Kerkau, BS, Paul Alabanza, BS, Amy James, BS, Som Siharath, BS, Tiffany Tribull, MS (UNC-CH); Saidi Kapiga, MD, ScD, George Seage, PhD (HSPH); Sten Vermund, MD, PhD, William Andrews, PhD, MD, Deedee Lyon, BS, MT(ASCP) Jeffrey Stringer, MD (UAB); NIAID Medical Officer: Samuel Adeniyi-Jones, MD; NICHD Medical Officer: Jennifer S. Read, MD, MS, MPH, DTM&H; NIAID Protocol Pharmacist: Scharla Estep, RPh, MS; Protocol Statisticians: Elizabeth R. Brown, ScD, Thomas R. Fleming, PhD, Anthony Mwatha, MS, Lei Wang, PhD, Ying Q. Chen, PhD (University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC)); Protocol Virologist: Susan Fiscus, PhD (UNC-CH); Protocol Operations Coordinator: Lynda Emel, PhD (Statistical Center for HIV/AIDS Prevention (SCHARP), FHCRC); Data Coordinators: Debra J. Lands, Ed.M, Ceceilia J. Dominique; Systems Analyst Programmers: Alice H. Fisher, BA, Martha Doyle (SCHARP, FHCRC); Protocol Specialist: Megan Valentine, PA-C, MS (Family Health International).

References

- 1.Read JS. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. In: Zeichner SL, Read JS, editors. Textbook of Pediatric HIV Care. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 111–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Working Group on Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV. Rates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Africa, America, and Europe: results from 13 perinatal studies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;8(5):506–510. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199504120-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Breastfeeding and HIV International Transmission Study (BHITS) Group. Late postnatal transmission of HIV-1 in breastfed children: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:2154–2166. doi: 10.1086/420834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taha T, Hoffman I, Fawzi W, Brown E, Read JS, Valentine M, et al. A phase III clinical trial of antibiotics to reduce chorioamnionitis-related perinatal HIV-1 transmission (HPTN024) AIDS. 2006;20:1313–1321. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000232240.05545.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guay L, Musoke P, Fleming T, Bagenda D, Allen M, Nakabiito C, et al. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Kampala, Uganda: HIVNET 012 randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354(9181):795–802. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boom R, Sol CJA, Salimans MMM, Jansen CL, et al. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28 (3):495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. 2. Wiley; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miotti PG, Taha TE, Kumwenda NI, et al. HIV transmission through breastfeeding: a study in Malawi. JAMA. 1999;282:744–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.8.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landesman SH, Kalish LA, Burns DN, et al. Obstetrical factors and transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from mother-to-child. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1617–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606203342501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semba RD, Kumwenda N, Hoover DR, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus load in breast milk, mastitis, and mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:93–98. doi: 10.1086/314854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Embree JE, Njenga S, Datta P, et al. Risk factors for postnatal mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. AIDS. 2000;14:2535–41. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200011100-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leroy V, Karon JM, Alioum A, et al. Postnatal transmission of HIV-1 after a maternal short-course zidovudine peripartum regimen in West Africa. AIDS. 2003;17:1493–1501. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200307040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pillay K, Coutsoudis A, York D, Kuhn L, Coovadia HM. Cell-free virus in breast milk of HIV-1-seropositive women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24:330–336. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200008010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Ioannidis JPA. Maternal cell-free viremia in the natural history of perinatal HIV-1 transmission: a meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;18:126–133. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199806010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson B, John-Stewart GC, Hughes JP, et al. Breast-milk infectivity in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected mothers. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:736–740. doi: 10.1086/374272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taha TE, Hoover DR, Kumwenda NI, et al. Late postnatal transmission of HIV-1 and associated factors. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:10–14. doi: 10.1086/518511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Read JS American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric AIDS. Human milk, breastfeeding, and transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the United States. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1196–1205. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]