Summary

“This is an author-produced version of a manuscript accepted for publication in The Journal of Immunology (The JI). The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. (AAI), publisher of The JI, holds the copyright to this manuscript. This version of the manuscript has not yet been copyedited or subjected to editorial proofreading by The JI; hence, it may differ from the final version published in The JI (online and in print). AAI (The JI) is not liable for errors or omissions in this author-produced version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the U.S. National Institutes of Health or any other third party. The final, citable version of record can be found at www.jimmunol.org.” Essential NK cell-mediated murine CMV (MCMV)3 resistance is under histocompatibility-2k (H-2k) control in MA/My mice. We generated a panel of intra-H2k recombinant strains from congenic C57L.M-H2k/b (MCMV resistant, Cmvr) mice for precise genetic mapping of the critical interval. Recombination breakpoint sites were precisely mapped and MCMV resistance/susceptibility traits were determined for each of the new lines to identify the MHC locus. Strains C57L.M-H2k(R7) (Cmvr) and C57L.M-H2k(R2) (MCMV susceptible, Cmvs) are especially informative; we found that allelic variation in a 0.3 megabase (Mb) interval in the class I D locus confers substantial difference in MCMV control phenotypes. When NK cell subsets responding to MCMV were examined, we found that Ly49G2+ NK cells rapidly expand and selectively acquire an enhanced capacity for cytolytic functions only in C57L.M-H2k(R7). We further show that depletion of Ly49G2+ NK cells before infection abrogated MCMV resistance in C57L.M-H2k(R7). We conclude that the MHC class I D locus prompts expansion and activation of Ly49G2+ NK cells that are needed in H-2k MCMV resistance.

Keywords: Rodent, Natural Killer Cells, MHC, Viral

Introduction

During virus infection, NK cells are needed in the body to provide early immune defense. Their activity is regulated by MHC class I-binding cell surface inhibitory and stimulatory receptors that include mouse Ly49, human KIR and NKG2/CD94 receptors (1-3). NK cell-mediated virus control is subject to genetic factors that can influence viral replication and host mortality (4). For instance, the Ly49H activation receptor displayed on the surface of NK cells in C57BL/6 mice binds MCMV m157 ligands at the surface of infected cells to impart MCMV resistance (5, 6). In NZW, MA/My and PWK strains, MCMV resistance also requires NK-mediated virus control, but Ly49H-independent defense mechanisms are key (7-11). It remains unclear what genetic factors are at work and how such factors mediate virus resistance through NK cells.

Attempts have been made to identify genetic factors which underlie MCMV resistance/susceptibility traits in offspring of genetic crosses between MA/My (Cmvr) and strains which display greater MCMV susceptibility (Cmvs). So far, major MCMV control loci have been mapped to the MHC and NK gene complex (NKC) on chromosomes 17 and 6, respectively (9, 10). We have further shown that MHC polymorphism is responsible for genetic variation in NK-mediated virus resistance in C57L.M-H2k and MA/My.L-H2b congenic mice (10, 12).

To pin down an MCMV control (Cmvr) locus within the MHC, we generated a genetic mapping panel of seventeen H-2k recombinant congenic lines on the C57L (Cmvs) genetic background. Recombination breakpoints were definitively mapped and MCMV resistance/susceptibility traits determined for each of the new lines so that the MHC Cmvr locus could be identified. Interestingly, virus infection clearly distinguished MCMV control in two of the novel lines, C57L.M-H2k(R2) (Cmvs) and C57L.M-H2k(R7) (Cmvr) which only differ by about 0.3-Mb DNA within the MHC. We further examined the role of NK subsets in MHC H-2k resistance to MCMV infection. We propose that the novel recombinant strains represent a powerful new model for investigating MHC regulation of NK-mediated virus immunity.

Materials and Methods

Animals

MA/My, C57L (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), MA/My.L-H2b (M.L-H2b) and C57L.M-H2k (L.M-H2k) mice were bred and maintained in a specific-pathogen-free vivarium at the University of Virginia, which is fully certified by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All recombinant congenic strains generated by and used in this study were backcrossed to the progenitor strain C57L for at least ten generations. All animal studies were approved by and conducted in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Committee.

Recombinant congenic strain generation, genetic markers and genotyping

(C57L.M-H2k × C57L)F1 or (MA/My.L-H2b × MA/My)F1 were brother × sister mated and screened for recombination crossovers within the D17Mit16-D17Uva09 interval using several simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) markers to distinguish MA/My and C57L alleles (Table 1). SSLP amplified PCR products were resolved in POP7-filled capillaries and analyzed on a Genetic Analyzer 3130xl using Data Collection (v3.0) and Genemapper software (v4.0, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as described previously (10). Some unlabeled SSLP amplicons were fractionated in 4% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized on a UV transilluminator after ethidium bromide staining.

Table I.

SSLP markers used for genetic mapping.

| Allele Sizeb (bp) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker | Chr. 17 Locusa (bp) | Primers (5′-3′) | C57BL/6 | MA/My | C57L |

| 17Uva12 | 34547552-34547799 | ACCAGCAAGCCCTATGTCAC TATGTCTACTGGTCAGGTTG |

248 | 250 | 245 |

| 17Uva18 | 34707366-34707702 | GTTCAGGGATACGGTGCTCC CCTTCTCTGATAAGACGGTC |

337 | ND | ND |

| 17Uva19 | 35099356-35099606 | GCGTTGTGACCCCTGGAGGC GAATGCCTGTCTCAGCACGG |

251 | ND | ND |

| 17Uva20 | 35143895-35144160 | GGGTGTTGGATGCTCCTGGA TACTGCCGAACCACTTCTCC |

266 | 271 | 266 |

| 17Uva15 | 35341805-35342016 | AGACAATGGCTAACAGAGGC TTCTATACAACCTGCCTGGA |

212 | 225 | 208 |

| 17Uva01 | 35375912-35376112 | GCAGCACTCTGTCTCTTTCC ATAGTAAGTCTCTGTCTCTC |

198 | 182 | 198 |

| 17Uva16 | 35406718-35406802 | CCTCCCATATTGGCTCTTCC GCAGTTGGACCTTTGACAGA |

85 | 126 | 81 |

| 17Uva17 | 35424300-35424711 | AGCGACTGAATATGGGTGAC GCAGGACTAACTGGATTGTC |

412 | 427 | 414 |

| 17Uva03 | 35451303-35451610 | TGCATGGGAAATACTCGTCC GGAGCTGACTCATCTCATTG |

308 | 291 | 311 |

| 17Uva14 | 36458241-36458469 | CCAAGGGCACTGTATTCCTG GACAAGTACCAAGTGCTCCT |

229 | 189 | 199 |

| 17Uva06 | 38389926-38390222 | AGGTGTTTATCAGCTGTAGG CAAGCCAACATTCAACATCA |

297 | 304 | 294 |

| 17Uva09 | 43168363-43168537 | AGCCCTGTCTCAAGTCAACG TCTGTGCCATTGACGTTAGC |

175 | 179 | 155 |

Chromosome locations for forward primers are based on C57BL/6 genomic sequence (Build 37, Ensembl Release 52).

Allele sizes based on electrophoretic mobility in POP7-filled capillaries run on a Genetic Analzyer 3130xl. 17UVA18 and 17UVA19 allele differences are based on electrophoresis in 4.0% agarose gel (data not shown) but exact sizes are not determined (ND).

For generation of novel SSLP markers, chromosome 17 sequence data available from the NCBI was manually inspected for microsatellite repeat sequences. Sequence specific primers were designed and tested for specific amplification of microsatellites and capacity for distinguishing SSLPs (Table 1). SNP markers rs13482961 and rs13482963 were amplified on the iCycler iQ Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol (Taqman SNPs, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Mice with intra-region recombinations were confirmed and further backcrossed to the C57L or MA/My genetic background, followed by more extensive genetic analysis to pinpoint chromosome crossovers as we have described previously (13). The novel recombinant lines have been maintained at the University of Virginia in accordance with IACUC guidelines.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

Anti-mouse CD3 (145-2C11) PerCP and APC, NK1.1 (PK136) PE, CD49b (DX5) PE, Ly49G2 (4D11) FITC, CD8α (53-6.7) PE and streptavidin-PerCP were purchased from BD Pharmingen. Anti-mouse CD4 (RM4-4) FITC, NK1.1 (PK136) PE-Cy7, Ly49C/I/F/H (14B11) biotin, NKG2D (CX5) PE, Ly49G2 (AT8) biotin, streptavidin-APC-Cy7 and perforin (prf1, eBioOMAK-D) APC were purchased from eBioscience. Anti-mouse CD69 (H1.2F3) APC was purchased from BioLegend. Anti-mouse NKp46 (goat IgG) PE was purchased from R&D Systems. Dr. Wayne Yokoyama kindly provided the PK136 hybridoma. Dr. Tim Bullock kindly provided rat IgG. The rat LGL-1 hybridoma 4D11 was purchased from ATCC. Purified PK136 and 4D11 mAbs were obtained from hybridoma supernatants at the University of Virginia Lymphocyte Culture Center.

Staining of spleen leukocyte surface antigens was performed as described previously (10). For intracellular perforin staining, cells were first stained for cell surface markers, then fixed and permeabilized using the CytoFix/CytoPerm kit (BD Pharmingen). All Ab stains were performed on ice. Ab-labeled cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACScan (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJo (version 8.0, Tree Star).

Virus assays

Salivary gland stock virus (SGV, Smith Strain, ATCC #VR194) was prepared after serial passage in BALB/c mice and titered on NIH3T3 or NIH3T12 monolayers as described (10, 12). SGV stocks 3.1.05 and 8.3.07 (LD50 = 1×105 PFU) stocks were used in this study. Experimental mice (8-12 wk) were i.p. infected with SGV (105 PFU or as indicated).

To study the role of NK cells during MCMV infection, mice were i.p. injected with 200 μg anti-NK1.1 mAb PK136 48 h before and where noted immediately prior to MCMV infection. Ly49G2+ NK cells were similarly depleted using 200 μg anti-Ly49G2 mAb 4D11 given 48 h before MCMV infection. NK cell depletions from spleen were confirmed by flow cytometry using anti-NKp46, anti-CD49b and anti-Ly49G2 AT8. For T cell depletions, mice were i.p. injected daily with 200 μg each of GK1.5 (anti-CD4) and 2.43 (anti-CD8) mAbs for three consecutive days (day -5, -4, -3) and one more dose three days later immediately before MCMV infection (day 0). T cell depletions were confirmed by flow cytometry using anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 mAb clones other than those used as depleting Abs (data not shown). Spleens and livers were collected from euthanized mice at 3.5 d post-infection (p.i.) for virus quantitation using quantitative real-time PCR as described previously (12). MCMV genome levels (average for triplicate measurements) were reported as the log10 (No. MCMV genomic copies / No. β-actin genomic copies).

Results

H-2k MCMV resistance mapped to the class I D subregion

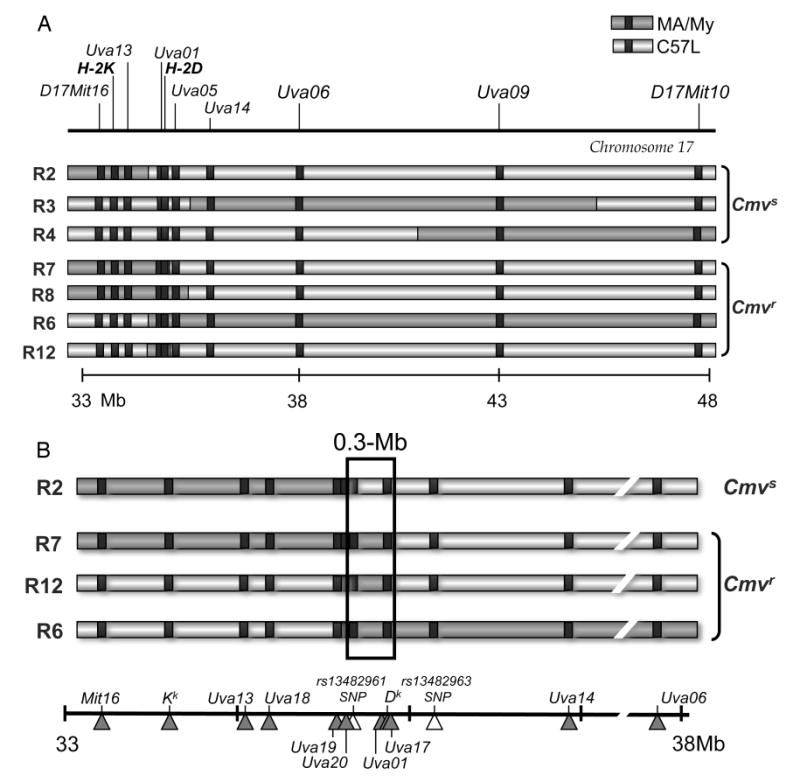

To identify a critical MCMV resistance interval between SSLP markers D17Mit16 and D17Mit10 (12), we generated a mapping panel of recombinant congenic strains (see Materials and Methods) on C57L (Cmvs) and MA/My (Cmvr) backgrounds. We screened for recombinant animals using a panel of SSLP genetic markers that distinguish MA/My and C57L alleles (Table 1 and Fig. 1A). In total, seventeen recombinant lines were isolated (Table 2); seven lines have been depicted in Figure 1 with recombinant chromosome crossover intervals in each of the lines mapped. For example, C57L.M-H2k(R2) (hereafter referred to as R2) mice retained MA/My-derived alleles in the D17Mit16-17Uva12 interval, and only C57L-derived alleles for 17Uva01 and markers distal to it (Table 2 and Fig. 1A). Thus, the R2 crossover was bounded by 17Uva12 and 17Uva01. Likewise, C57L.M-H2k(R7) (R7 hereafter) mice retained MA/My-derived alleles in the D17Mit16-H2D interval and C57L-derived alleles for 17Uva03 and markers distal to it. Thus, the R7 crossover occurred between H-2D and 17Uva03. A similar strategy was used to locate crossovers for each of the recombinant lines; together the lines established a valuable genetic mapping resource.

Figure 1. Genetic mapping of H-2k-linked MCMV resistance in chromosome 17 recombinant congenic strains.

A panel of seventeen recombinant congenic mouse lines (Table II) was generated and genotyped with genetic markers (Table I) to pinpoint chromosome 17 crossover sites. A. A chromosome 17 physical map between D17Mit16 and D17Mit10 (based on C57BL/6 genome, Build 37) is shown with a reference scale in megabases (Mb) included below. Also depicted are seven informative recombinant chromosome haplotypes with C57L- (light gray) or MA/My- (dark gray) derived intervals based on genetic analysis of the new mouse lines. B. A refined haplotype map for the critical genetic region based on genotype analysis of the four most informative intra-H-2 recombinant lines. SNP (∆) and SSLP (▲) genetic marker positions are indicated.

Table II.

Genetic analysis of chromosome 17 recombinant lines.

| Locusa | Recombinant linesb | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57L.M-H2k | MA/My.L-H2b | ||||||||||||||||

| M | M | M | M | ||||||||||||||

| R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | R9 | R10 | R11 | R12 | R13 | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | |

| D17Mit16 | M | M | L | L | L | L | M | M | M | M | M | L | L | L | M | M | L |

| H-2K | M | M | L | L | L | L | M | M | M | M | ND | L | L | L | M | M | L |

| 17Uva12 | M | M | L | L | M | L | M | M | M | M | L | L | L | L | M | M | L |

| 17Uva01 | M | L | L | L | M | M | M | M | M | M | L | M | M | M | M | M | M |

| H-2D | M | L | L | L | M | M | M | M | ND | M | L | M | M | M | M | M | M |

| 17Uva03 | M | L | L | L | M | M | L | M | L | M | L | L | L | M | M | M | M |

| 17Uva06 | M | L | M | L | M | M | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | M | M | L | M |

| 17Uva09 | M | L | M | M | M | M | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | M | M | L | M |

| D17Mit10 | L | L | L | M | M | M | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | M | L | L | M |

Chromosome 17 locus markers (see Table I) used to determine MA/My (M) or C57L (L) alleles for the recombinant chromosome in each line are shown. Some alleles are not determined (ND).

Recombinant lines were generated on C57L (denoted as R) or MA/My (denoted as MR) backgrounds.

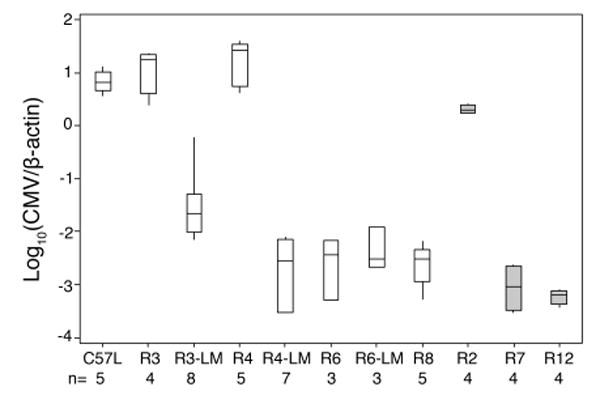

We next separately backcrossed each new mouse line with C57L to generate heterozygous offspring. About half of the offspring received a recombinant chromosome haplotype, and the other half received a non-recombinant C57L.M-H2k-derived haplotype. We compared the recombinant offspring and their non-recombinant littermates for MCMV control traits by assessing spleen and liver (not shown) virus genome levels 3.5 days after infection. As shown in Figure 2, only low MCMV titers were observed in R6, R7, R8 and R12 spleens, similar to R6-LM littermate control spleen. Thus, an MCMV resistance (Cmvr) locus should reside in the region of overlap. In contrast, MCMV was substantially higher in R2, R3 and R4 spleens than in R3-LM and R4-LM littermates, indicating that MA/My-derived haplotypes retained in these recombinant lines are insufficient in MCMV resistance. Altogether, the data in Figure 2 pointed toward a critical interval bounded by R2 and R7 crossovers. An H-2kCmvr locus was first placed in the H-2 S-D region flanked by markers 17Uva12 and 17Uva03.

Figure 2. MHC H-2k MCMV resistance maps to the class I D locus.

The recombinant congenic mouse lines in Table II (heterozygous for chromosome 17 haplotypes) were backcrossed to C57L. Offspring with a recombinant chromosome and several littermate controls (denoted LM for the indicated line) without a recombinant chromosome were infected with MCMV. After 90 h, spleen and liver (not shown) MCMV genome levels were determined. Interquartile range and the median values are shown, with whisker extensions to extreme values. Open and grey boxes indicate infections with 3.1.05 or 8.3.07 SGV stocks, respectively. The numbers of mice used in each group are indicated at the bottom. The box plot was created with Minitab 15 (Minitab, Inc., State College, PA). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

To refine the locus, R2, R7 and R12 were genotyped with additional allele-specific markers located near the H-2 class I D gene (Table 3 and Fig. 1). By this strategy, R2 and R7 crossovers were mapped between 17Uva20 and SNP rs13482961 and 17Uva17 and 17Uva03, respectively. Thus, an H-2k Cmvr locus must be flanked by markers 17Uva20 and 17Uva03, an ∼0.3-Mb interval that spans 30 genes including the class I D gene (supplemental Fig. S1). In accord with this, R12, which arose spontaneously from the R7 line, also displays the resistance phenotype (Fig. 2).

Table III.

Refined genetic mapping of informative H-2 recombinant lines.

| Locusa | C57L.M-H2k recombinant lines | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | R12 | R7 | R6 | |

| 17Uva12 | M | L | M | L |

| 17Uva18 | M | L | M | L |

| 17Uva19 | M | L | M | L |

| 17Uva20 | M | L | M | L |

| rs13482961b | L | M | M | M |

| 17Uva15 | L | M | M | M |

| 17Uva01 | L | M | M | M |

| H-2 D | L | M | M | M |

| 17Uva16 | L | M | M | M |

| 17Uva17 | L | M | M | M |

| 17Uva03 | L | L | L | M |

| rs13482963b | L | L | L | M |

| 17Uva14 | L | L | L | M |

| 17Uva06 | L | L | L | M |

H-2 locus markers (see Table I) used to determine MA/My (M) or C57L (L) alleles for the critical locus are shown.

SNP markers (see Materials and Methods) used to help refine the genetic locus.

NK cells are required in H-2k MCMV resistance

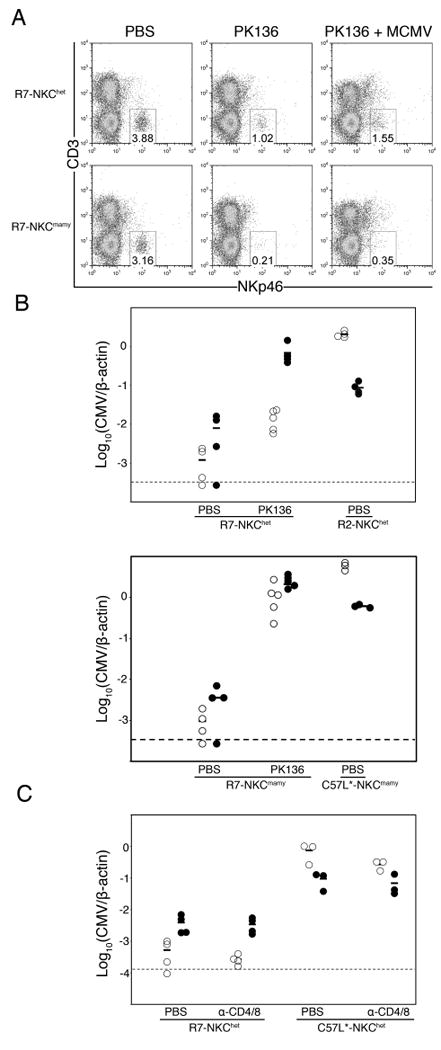

To assess their role in resistance, we depleted NK cells from R7 (Cmvr) mice before MCMV infection. Our previous work had shown that the anti-NK1.1 mAb PK136 does not efficiently deplete NK cells from mice on the C57L (NK1.1c57l) background (10). Consequently, when C57L.M-H2k/b-NKCmamy/c57l mice with an NK1.1c57l allele were given PK136 treatment before MCMV infection, only a partial loss of splenic MCMV resistance was observed (10). Residual MCMV control was likely due to ineffective depletion of NK cells from NK1.1c57l mice (data not shown).

To achieve efficient NK depletion, the NKCmamy haplotype was crossed onto the R7 genetic background and homozygous R7-NKCmamy animals were generated. As shown in Figure 3A, PK136 treatment efficiently depleted ∼78% and >93% of splenic NKp46+ NK cells from R7-NKChet and R7-NKCmamy mice, respectively. Similar results were obtained by staining for residual NK cells with anti-CD49b (DX5) or anti-NKG2D mAb (data not shown). In accord with NK depletion from C57L.M-H2k/bNKChet mice (10), MCMV control in R7-NKChet mice was consistently more dramatically altered in the liver than in the spleen (Fig. 3B). Nonetheless, PK136 depletion of R7-NKCmamy NK cells fully abrogated spleen and liver MCMV control (Fig. 3B). We conclude that NK cells are essential to MHC H-2k MCMV resistance. Strains R2 and R7 establish an excellent model system to investigate NK-mediated virus immunity under MHC genetic control.

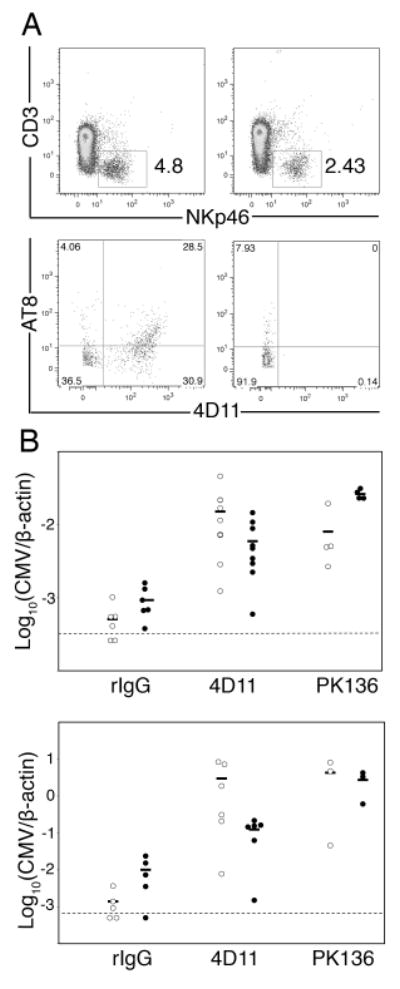

Figure 3. A requirement for NK cells in MHC H-2k MCMV resistance.

A. Splenocytes from R7-NKChet and R7-NKCmamy (Cmvr) mice given PBS, anti-NK1.1 mAb PK136, or PK136 followed by MCMV infection were stained for CD3 and NKp46. Numbers indicate the percentage of splenocytes within the NKp46+CD3- lymphocyte gate. B. R2 (Cmvs), R7 (Cmvr), C57L and PK136 treated mice were infected with MCMV. Shown are spleen (open) and liver (filled) MCMV genome levels for individual animals 90 h after infection. C. R7, C57L and T-cell-depleted (anti-CD4/CD8; see Materials and Methods) mice were infected with MCMV. Shown are spleen (open) and liver (filled) MCMV genome levels for individual animals 90 h after infection. Data included 3-5 mice per group.

To address a potential role for other lymphocyte subsets, we also assessed resistance in mice after depletion of CD4 and CD8 T cells, as the importance of both subsets has been established (14, 15). Further, recent work has shown that in BALB.Klra8 congenic mice with Ly49H resistance, MCMV-specific activated CD8 T cells in the spleen can be detected by day 4 post-infection (16). As shown in Figure 3C, T cell depletions failed to alter MCMV replication in the spleens or livers of infected mice and thus these cells have no measurable impact in early MHC H-2k MCMV resistance.

Selective activation and expansion of Ly49G2+ NK cells confers H-2k MCMV resistance

The activating Ly49H receptor mediates NK dependent MCMV control in B6 mice (17-19). In accord, Ly49H+ NK cells specifically expand and proliferate to counter MCMV (20). We hypothesized therefore that some NK cells might undergo selective expansion and/or activation in R7 (Cmvr) mice during infection. Ly49G2 is an especially interesting inhibitory NK cell receptor because Ly49G2129 can bind MHC class I Dk as a ligand (21, 22). In addition, we found that only one amino acid difference distinguishes Ly49G2mamy from Ly49G2c57l and Ly49G2129 alleles (unpublished data). Thus, NK cell subset responses were examined in R2 and R7 mice at discrete times after MCMV infection.

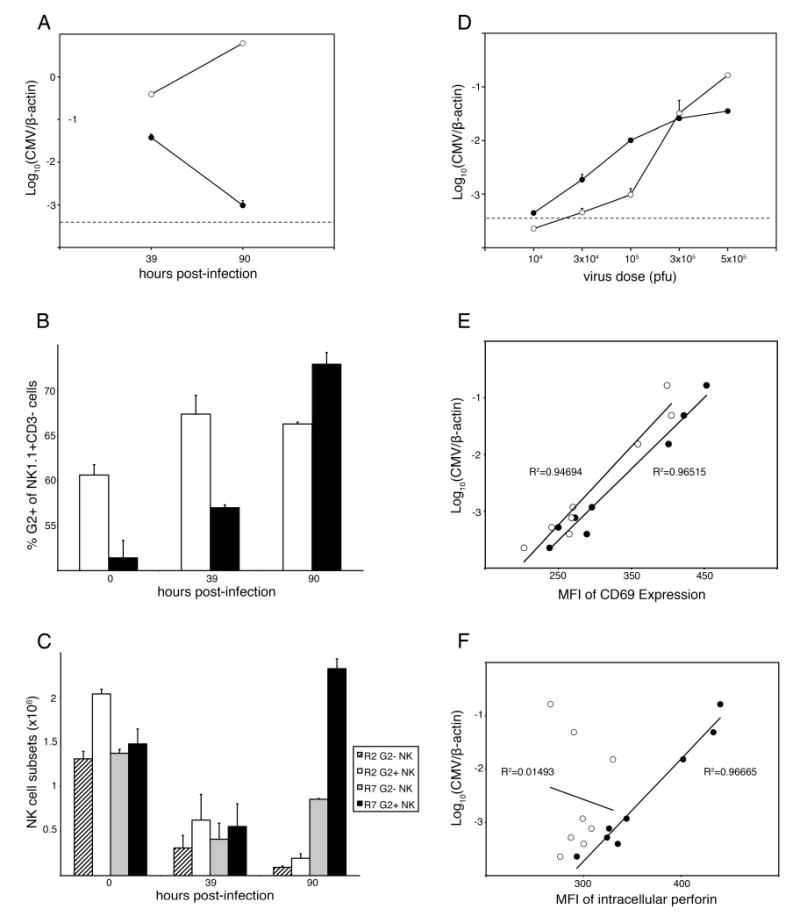

To examine Ly49+ NK subsets responding to MCMV, we stained splenic NK cells using anti-Ly49 mAbs 14B11 (pan-specific for Ly49C/I/F/H) and 4D11 (Ly49G2-specific) before and after infection in R2 (Cmvs) and R7 (Cmvr) congenic strains. As expected, splenic MCMV was substantially higher in R2 than R7 after 90 h (Fig. 4A). We found that 45-50% of NK cells in C57L and MA/My spleens can be stained with mAb 14B11 (data not shown). On the other hand, different subsets of NK cells in C57L (∼50%) or MA/My (∼30%) express Ly49G2 on the cell surface (data not shown). In R2 and R7 (both on the C57L genetic background) mice, 50-60% of NK cells display Ly49G2 on the cell surface before infection (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Ly49G2+ NK cells respond selectively to MCMV infection.

R2 and R7 mice were infected with 105 PFU MCMV (A-C) or with the indicated dose in the range 104 to 5 × 105 PFU (D-F). A. Average MCMV genome levels for R2 (open) and R7 (filled) spleens are shown. B. R2 (open) and R7 (filled) splenocytes were stained for NK1.1, CD3 and Ly49G2 (4D11). Numbers indicate the mean percentage of NK cells expressing Ly49G2+ at the cell surface at the indicated times after MCMV infection. C. As in B, but values represent total numbers of G2+ and G2- NK cells in R2 and R7 spleens after infection. R2 NK cells in spleen, regardless of G2 expression, decreased at 90 h after infection (P < 0.005). In R7 spleen, G2- NK cells decreased by 39 h after infection and were still significantly lower than in control spleen at 90 h after infection (P < 0.005). On the other hand, only R7 G2+ NK cells increased significantly between 39-90 h after infection until they were also higher than in uninfected R7 spleen (P < 0.05). D. Groups of R7 mice were infected with the indicated dose of MCMV. Shown are average MCMV genome levels for spleen (open) and liver (filled) at 90 h after infection. The limit of MCMV detection (dashed line) is indicated. E. and F. Splenocytes from R7 mice in (D) were stained for NK1.1, Ly49G2 (4D11) and cell surface CD69 (E) or intracellular perforin (F). Plots show MCMV genome levels and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values for G2- (open) and G2+ (filled) NK cell subsets for individual animals. The correlation exponential trend lines with R2 values are shown. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student T-test.

Comparison of 14B11+ and 14B11- NK cells in R2 and R7 mice revealed little, if any, change in either percentage or cell numbers after infection (data not shown). In contrast, a slight increase in the percentage of Ly49G2+ NK1.1+ CD3- NK cells was observed in R2 spleen by 39 h after infection, and the percentage of Ly49G2+ NK1.1+ CD3- NK cells rose steadily through 90 h after infection in R7 spleen (Fig. 4B). Even so, splenic NK cells showed an overall decline in number in both strains by 39 h after infection (Fig. 4C), consistent with splenic NK cells responding to MCMV in B6 mice (19, 20, 23). After 39 h however, G2+ NK cells increased significantly in R7 mice to a level that exceeded steady state levels in uninfected controls (Fig. 4C). This was not the case for G2- NK cells in R7 mice, or either subset in R2 mice (Fig. 4C). We have observed similar expansion of G2+ NK cells in infected MA/My mice (data not shown). This data is congruent with the finding of Welsh and colleagues showing a proportional increase in Ly49G2+ NK cells after MCMV infection in B6 mice (19, 23). More remarkable here however, the absolute number of Ly49G2+ NK cells and the proportion of NK cells is significantly augmented under H-2k control. These data therefore indicate that splenic Ly49G2+ NK cells are selectively expanded in response to MCMV infection in R7 mice with highly efficient H-2k NK-mediated virus control.

We have previously shown that the peak and extent of NK intracellular IFN-γ in response to MCMV is similar in MA/My and C57L mice (12). Thus, we examined R2 and R7 NK cells for cell surface CD69 and intracellular perforin (prf1) expression in response to MCMV. We delivered MCMV to mice in a dose range that yielded different spleen (∼1,000-fold variation) and liver (∼100-fold variation) MCMV levels by 90 h after infection. In accord with previous NK IFN-γ data (12), CD69 activation in R2 and R7 NK cells correlated well with splenic MCMV (data not shown). In addition, G2+ and G2- NK cells in R7 had enhanced CD69 expression that corresponded with spleen MCMV (Fig. 4E).

We next examined perforin in NK cells responding to MCMV. Similar to CD69 expression, R7 G2+ NK cells expressed perforin levels that corresponded directly to splenic MCMV over a wide range (Fig. 4F). In contrast, perforin levels in R7 G2- NK cells did not correlate with spleen MCMV loads in the inoculation range 104 to 5 × 105 PFU (Fig. 4F). We further observed peak expansion of total NK cells and a maximal G2+/G2- NK cell ratio in R7 mice given 105 pfu MCMV at 90 h after infection (supplemental Fig. S2B). In contrast, G2+ NK cells in R2 mice declined by 3-fold even at the lowest MCMV dose tested (supplemental Fig. S2A). Hence, MCMV provoked potent induction of perforin and acquisition of cytolytic effector status by G2+ NK cells in R7 mice. We conclude that R7 G2+ NK cells preferentially expand and become activated during MCMV infection due to the MHC class I Dk subregion.

To discern their involvement in virus resistance, Ly49G2+ NK cells were depleted from R7 (Cmvr) mice using mAb 4D11 given before infection. In spleens of 4D11 treated R7 mice, we found a selective loss of about 35% of NKp46+ CD3-CD19- splenocytes and residual NK cells (includes 14B11+ and 14B11-) in these animals were refractory to staining with 4D11 or AT8 (also Ly49G2-specific) (Fig. 5A). Intriguingly, 4D11 treatment also significantly diminished resistance such that virus replication was enhanced in spleen and liver in animals after MCMV infection (Fig. 5B and C). In comparison, PK136 depletion of most NK1.1+ cells gave an effect comparable in magnitude. Inasmuch as Ly49G2 NK subset depletion from C57BL/6 mice using 4D11 or 4LO439 mAbs given before infection has no effect on resistance in the spleen or liver (23, 24), our data indicate that Ly49G2+ NK-mediated resistance is selective and that residual NK subsets are ineffective in this genetic setting. We conclude that the H-2k class I D locus confers MCMV resistance through Ly49G2+ NK cells in R7 mice.

Figure 5. Ly49G2+ NK cells required in MCMV resistance.

A. Splenocytes from rat IgG or 4D11 treated R7 (Cmvr) mice with MCMV infection were stained for CD3, NKp46, AT8 and 4D11. At top, numbers indicate the percentage of splenocytes within the NKp46+CD3- lymphocyte gate. Shown below, plots are gated on NKp46+CD3- lymphocytes. Left plots show splenocytes from rat IgG treated mice. Right plots show splenocytes from mAb 4D11 treated mice. B. Spleen (open) and liver (filled) MCMV genome levels for IgG, 4D11 or PK136 treated R7 mice infected with 103 (top) or 104 (bottom) PFU MCMV are shown. For both virus doses, 4D11-treated spleen virus levels were significantly higher than that of rat IgG-treated animals (P < 0.005), though not significantly different than PK136-treated animals. At the lower dose, 4D11-treated liver virus levels were significantly higher than rat IgG treated (P < 0.05), but significantly lower than PK136 treated animals (P < 0.05). Statistical analysis was performed using a Mann-Whitney/Wilcoxon test. Data included 3-9 mice per group.

Discussion

H-2k genetic resistance to lethal MCMV infection was previously mapped to MHC K/I-A and D intervals using MHC recombinant congenic mice (25). Later, a key role for NK-mediated MCMV resistance in MA/My mice was shown (7). Only recently however, has it come to light that MA/My resistance is largely affected by a dominant H-2k locus which can contribute MCMV control through epistatic (9) or additive ((10) and M.S. and M.G.B., unpublished data) interaction with an NKC locus on chromosome 6. Although we did not observe a K/I-A-associated resistance effect in this study, distinct background gene or allele effects in C3H, B10 and BALB.K strains could have influenced H-2k resistance to MCMV mortality in the former study (25). Nevertheless, here we extended precise genetic mapping for an H-2k Cmvr locus to a narrow class I D interval spanning 0.3-Mb DNA with roughly 30 genes.

Though multiple genes at this locus encode proteins with at least some immune function, EG667612, lymphotoxin, tumor necrosis factor and class I D genes are especially interesting in consideration of a possible role in virus resistance. EG667612 sequence includes an Ncr3 pseudogene for mouse NKp30 and it is not expressed in a variety of different mouse strains (26) including MA/My (X.X. and M.G.B., unpublished data). Lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor cytokines contribute important immune functions with potential to influence innate resistance to viruses, including MCMV (27-29). The class I D molecule is also an excellent positional candidate for H-2k Cmvr. NK cell receptors have as their ligands MHC class I molecules, which therefore can influence NK self-tolerance and effector functions. Because MHC-I is targeted by MCMV proteins for down-regulation after infection (30), including Dk cell surface expression which is rapidly diminished (12), NK cells with self-MHC inhibitory receptors should in principle readily respond to MCMV infection.

Only Ly49H has so far been coupled with virus recognition and resistance due to specific binding to its m157 ligand displayed by MCMV infected cells (5, 6). Also implicated in MCMV recognition and resistance, Ly49P+ reporter cells can respond specifically to Dk-expressing MCMV infected cells (9). In support of a potential in vivo role, a pan-specific anti-Ly49 mAb YE1/48 with reactivity for Ly49A/P/V/T given before infection can interfere with MCMV resistance in MA/My mice (9). Genetic map analysis in the current work establishes a critical involvement for the MHC-I Dk locus in vivo. We found unexpectedly that Ly49G2+ NK cells can selectively respond during MCMV infection with expansion and activation when H-2k protection (i.e. in the R7 genetic setting) is available. Similar features were not observed for G2+ NK cells in R2 (Cmvs) mice, or for G2- or 14B11+ NK subsets in either strain after infection. Others have already noted that the frequency of Ly49G2+ NK cells increases in the spleens, peritoneal cavities, and livers of C57BL/6 mice by day 3 after MCMV infection as well as during the course of other viral infections, including mouse hepatitis virus, vaccinia virus, and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infections (19, 23). Ly49G2 is therefore not a bona fide marker for NK cells providing protection from MCMV infection in C57LBL/6 animals. In stark contrast with MCMV resistance manifest in the C57BL/6 strain, we found herein that Ly49G2-depleted R7 animals with about 65% of NKp46+ NK cells intact were severely deficient for MCMV resistance. Other NK cell subsets were therefore unable to effectively deliver MCMV resistance in this system. Altogether, these data substantiate a likely critical role, one influenced by MHC genetic variation, for Ly49G2+ NK cells in MCMV resistance in the R7 strain.

MAb 4D11 likely specifically binds the inhibitory Ly49G2c57l receptors expressed by R7 NK cells for several reasons: 1) We found that the C57L and 129 NKC-Ly49 haplotypes are highly related, if not identical (31); 2) Sequence analysis of Ly49G2c57l revealed that it is identical to Ly49G2129; Ly49G2mamy differs by one amino acid (J. Prince, A. Lundgren and M.G.B., unpublished data); 3) 4D11 was shown specific for Ly49G2 receptors on C57BL/6, BALB/c, C3H and 129 NK cells (32, 33); and 4) another Ly49G2 allele-specific mAb AT8 (33) similarly co-stained IL-2 activated 4D11+ NK cells from 129, R2-NKCmamy and R7-NKCmamy mice (Supplemental Fig. S3). Primary 4D11+ NK cells from uninfected and MCMV infected R7-NKCmamy mice were also co-stained with mAb AT8 (data not shown). Collectively, these data substantiate mAb 4D11 specific recognition of Ly49G2c57l and Ly49G2mamy NK receptors.

It has been shown that Ly49H+ splenic NK cells, which are needed for MCMV control in C57BL/6 mice, preferentially expand by day 6 after infection (20). More intriguing in this system, G2+ NK cells rapidly expanded in MCMV infected R7 spleens by 90 h after infection. The 14B11+ NK subset was not similarly affected (data not shown). Further, we found that R2 and R7 NK cells displayed classical signs of early activation (CD69+) after infection, but only R7 G2+ NK cells acquired high perforin expression with enhanced cytotoxic potential. We speculate that selective expansion and activation of G2+ NK cells was due to Dk expression in R7 mice. While cytokine stimulation (e.g. IL-2 or IL-15) is important for perforin activation (34), this finding further suggests that G2+ NK cells may have better access to cytokine stimulation than other NK subsets in R7, or any NK subsets in R2. This feature further distinguishes H-2k and Ly49H MCMV control since both Ly49H+ and Ly49H- NK cells have enhanced perforin expression after infection in B6 mice (34).

Because Ly49P has been shown to recognize MCMV-experienced Dk molecules on infected cells (9), its coexpression with Ly49G2 on NK cells could help to explain selective expansion during MCMV infection. So far, we have been unable to directly address this possibility since anti-Ly49 mAbs, YE1/32 and YE1/48 poorly recognize primary Ly49P+ NK cells from 129 (32) and C57L and MA/My spleens (data not shown). Nonetheless, G2+ and G2- NK cells should have similar variegated Ly49P expression (3) before and 48 h after MCMV infection when both NK subsets were comparable in R2 (Cmvs) and R7 (Cmvr) mice (Fig. 4C). One may expect G2+P+ and G2-P+ NK cells to have expanded in a similar fashion after early Ly49P recognition of MCMV-Dk on infected cells. Instead, only G2+ NK cells selectively expanded and became activated for cytolytic function in R7 spleen. Thus, although the actual role of Ly49G2 in NK activation must still be determined, the G2+ NK subset may have been more effectively licensed (35) or armed (36) for effector function and/or responsive to cellular alterations in self-MHC class I expression, perhaps due to viral down-regulation of H-2 Dk cell surface expression (12). Consistent with this possibility, inhibitory Ly49G2balb and Ly49G2129 receptors can specifically bind MHC-I Dk (21, 22) and Ly49G2c57l is identical to Ly49G2129 (unpublished data).

Though mouse Ly49 and human KIR receptors are structurally unrelated, they have several features in common, including sequence polymorphism, MHC-I recognition and signaling through ITAM (on co-receptors) or ITIM domains for stimulating or inhibiting NK effector functions, respectively. Recent genetic studies have revealed that certain KIR / HLA combined genotypes associate with resistance or susceptibility to some human diseases (37), but the mechanistic details have not been elucidated. We propose that further study of NK-mediated virus immunity under MHC genetic control will provide an important model to begin to examine a role for NK cell receptors, as they can be influenced by MHC alleles, in virus immunity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pearl Sabastian for generation of genetic markers, Tony Scalzo and Virginia Carroll for comments on the manuscript and Tim Bullock and Bill Petri for reagents provided.

Footnotes

Grant Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Grant R01 AI050072.

Abbreviations: Cmvr, MCMV resistant; Cmvs, MCMV susceptible; G2+, Ly49G2+; G2-, Ly49G2-; LM, littermate; MCMV, Murine CMV; Mb, megabases; NKC, NK gene complex; QPCR, quantitative real-time PCR; R2, C57L.M-H2k(R2); R7, C57L.M-H2k(R7); SGV, salivary gland virus; SSLP, simple sequence length polymorphism; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism

References

- 1.Lanier LL. NK Cell Recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:225–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yokoyama WM, Kim S, French AR. The dynamic life of natural killer cells. Annual Review of Immunology. 2004;22:405–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gasser S, Raulet DH. Activation and self-tolerance of natural killer cells. Immunological Reviews. 2006;214:130–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown MG, Scalzo AA. NK gene complex dynamics and selection for NK cell receptors. Sem Immunol. 2008;20:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith HRC, Heusel JW, Mehta IK, Kim S, Dorner BG, Naidenko OV, Iizuka K, Furukawa H, Beckman DL, Pingel JT, Scalzo AA, Fremont DH, Yokoyama WM. Recognition of a virus-encoded ligand by a natural killer cell activation receptor. PNAS. 2002;99:8826–8831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092258599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arase H, Mocarski ES, Campbell AE, Hill AB, Lanier LL. Direct Recognition of Cytomegalovirus by Activating and Inhibitory NK Cell Receptors. Science. 2002;296:1323–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.1070884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scalzo AA, Lyons PA, Fitzgerald NA, Forbes CA, Yokoyama WM, Shellam GR. Genetic mapping of Cmv1 in the region of mouse chromosome 6 encoding the NK gene complex-associated loci Ly49 and musNKR-P1. Genomics. 1995;27:435–441. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez M, Sabastian P, Clark P, Brown MG. Cmv1-independent antiviral role of NK cells revealed in murine cytomegalovirus infected New Zealand White mice. J Immunol. 2004;173:6312–6318. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.6312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desrosiers MP, Kielczewska A, Loredo-Osti JC, Adam SG, Makrigiannis AP, Lemieux S, Pham T, Lodoen M, Morgan K, Lanier LL, Vidal SM. Epistasis between mouse Klra and major histocompatibility complex class I loci is associated with a new mechanism of natural killer cell-mediated innate resistance to cytomegalovirus infection. Nat Genet. 2005;37:593–599. doi: 10.1038/ng1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dighe A, Rodriguez M, Sabastian P, Xie X, McVoy MA, Brown MG. Requisite H2k role in NK cell-mediated resistance in acute murine CMV infected MA/My mice. J Immunol. 2005;175:6820–6828. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adam SG, Caraux A, Fodil-Cornu N, Loredo-Osti JC, Lesjean-Pottier S, Jaubert J, Bubic I, Jonjic S, Guenet JL, Vidal SM, Colucci F. Cmv4, a New Locus Linked to the NK Cell Gene Complex, Controls Innate Resistance to Cytomegalovirus in Wild-Derived Mice. J Immunol. 2006;176:5478–5485. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie X, Dighe A, Clark P, Sabastian P, Buss S, Brown MG. Deficient major histocompatibility complex-linked innate murine cytomegalovirus immunity in MA/My.L-H2b mice and viral downregulation of H-2k class I proteins. J Virol. 2007;81:229–236. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00997-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scalzo AA, Wheat R, Dubbelde C, Stone LR, Clark P, Forbes CA, Du Y, Dong N, Stoll J, Yokoyama WM, Brown MG. Molecular genetic characterization of the distal NKC recombination hotspot and putative murine CMV resistance control locus. Immunogenetics. 2003;55:370–378. doi: 10.1007/s00251-003-0591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polic B, Hengel H, Krmpotic A, Trgovcich J, Pavic I, Lucin P, Jonjic S, Koszinowski UH. Hierarchical and Redundant Lymphocyte Subset Control Precludes Cytomegalovirus Replication during Latent Infection. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1047–1054. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krmpotic A, Bubic I, Polic B, Lucin P, Jonjic S. Pathogenesis of murine cytomegalovirus infection. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:1263–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robbins SH, Bessou G, Cornillon Ael, Zucchini N, Rupp B, Ruzsics Z, Sacher T, Tomasello E, Vivier E, Koszinowski UH, Dalod M. Natural Killer Cells Promote Early CD8 T Cell Responses against Cytomegalovirus. PLoS Pathogens. 2007;3:1152–1164. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown MG, Dokun AO, Heusel JW, Smith HRC, Beckman DL, Blattenberger EA, Dubbelde CE, Stone LR, Scalzo AA, Yokoyama WM. Vital Involvement of a natural killer cell activation receptor in resistance to viral infection. Science. 2001;292:934–937. doi: 10.1126/science.1060042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SH, Girard S, Macina D, Busa M, Zafer A, Belouchi A, Gros P, Vidal SM. Susceptibility to mouse cytomegalovirus is associated with deletion of an activating natural killer cell receptor of the C-type lectin superfamily. Nature Genetics. 2001;28:42–45. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniels KA, Devora G, Lai WC, O'Donnell CL, Bennett M, Welsh RM. Murine Cytomegalovirus Is Regulated by a Discrete Subset of Natural Killer Cells Reactive with Monoclonal Antibody to Ly49H. J Exp Med. 2001;194:29–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dokun AO, Kim S, Smith HR, Kang HS, Chu DT, Yokoyama WM. Specific and nonspecific NK cell activation during virus infection. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:951–956. doi: 10.1038/ni714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silver ET, Lavender KJ, Gong DE, Hazes B, Kane KP. Allelic variation in the ectodomain of the inhibitory Ly-49G2 receptor alters its specificity for allogeneic and xenogeneic ligands. J Immunol. 2002;169:4752–4760. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makrigiannis AP, Pau AT, Saleh A, Winkler-Pickett R, Ortaldo JR, Anderson SK. Class I MHC-binding characteristics of the 129/J Ly49 repertoire. J Immunol. 2001;166:5034–5043. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.5034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tay CH, Yu LY, Kumar V, Mason L, Ortaldo JR, Welsh RM. The role of LY49 NK cell subsets in the regulation of murine cytomegalovirus infections. J Immunol. 1999;162:718–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Depatie C, Chalifour A, Pare C, Lee SH, Vidal SM, Lemieux S. Assessment of Cmv1 candidates by genetic mapping and in vivo antibody depletion of NK cell subsets. Int Immunol. 1999;11:1541–1551. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.9.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grundy JE, Mackenzie JS, Stanley NF. Influence of H-2 and non-H-2 genes on resistance to murine cytomegalovirus infection. Infect Immun. 1981;32:277–286. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.1.277-286.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollyoake M, Campbell RD, Aguado B. NKp30 (NCR3) is a Pseudogene in 12 Inbred and Wild Mouse Strains, but an Expressed Gene in Mus caroli. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1661–1672. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orange JS, Biron CA. Characterization of early IL-12, IFN-alphabeta, and TNF effects on antiviral state and NK cell responses during murine cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol. 1996;156:4746–4756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yerkovich ST, Olver SD, Lenzo JC, Peacock CD, Price P. The roles of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 and interleukin-12 in murine cytomegalovirus infection. Immunology. 1997;91:45–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider K, Loewendorf A, De Trez C, Fulton J, Rhode A, Shumway H, Ha S, Patterson G, Pfeffer K, Nedospasov SA, Ware CF, Benedict CA. Lymphotoxin-mediated crosstalk between B cells and splenic stroma promotes the initial type I interferon response to cytomegalovirus. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hengel H, Reusch U, Gutermann A, Ziegler H, Jonjic S, Lucin P, Koszinowski UH. Cytomegaloviral control of MHC class I function in the mouse. Immunol Rev. 1999;168:167–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown MG, Scalzo AA, Stone LR, Clark P, Du Y, Palanca B, Yokoyama WM. Nkc allelic variability among inbred mouse strains: Evidence for Nkc haplotypes. Immunogenetics. 2001;53:584–591. doi: 10.1007/s002510100365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortaldo JR, Mason AT, Winkler-Pickett R, Raziuddin A, Murphy WJ, Mason LH. Ly-49 receptor expression and functional analysis in multiple mouse strains. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:512–520. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makrigiannis AP, Rousselle E, Anderson SK. Independent control of Ly49g alleles: implications for NK cell repertoire selection and tumor cell killing. J Immunol. 2004;172:1414–1425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fehniger TA, Cai SF, Cao X, Bredemeyer AJ, Presti RM, French AR, Ley TJ. Acquisition of Murine NK Cell Cytotoxicity Requires the Translation of a Pre-existing Pool of Granzyme B and Perforin mRNAs. Immunity. 2007;26:798–811. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim S, Poursine-Laurent J, Truscott SM, Lybarger L, Song Y, Yang L, French AR, Sunwoo JB, Lemieux S, Hansen TH, Yokoyama WM. Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature. 2005;436:709–713. doi: 10.1038/nature03847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez NC, Treiner E, Vance RE, Jamieson AM, Lemieux S, Raulet DH. A subset of natural killer cells achieves self-tolerance without expressing inhibitory receptors specific for self-MHC molecules. Blood. 2005;105:4416–4423. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bashirova AA, Martin MP, McVicar DW, Carrington M. The killer immunoglobulin-like receptor gene cluster: tuning the genome for defense. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:277–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.