Abstract

Within the vestibular system of virtually all vertebrate species, gravity and linear acceleration are detected via coupling of calcified masses to the cilia of mechanosensory hair cells. The mammalian ear contains thousands of minute biomineralized particles called otoconia, whereas the inner ear of teleost fish contains three large ear stones called otoliths that serve a similar function. Otoconia and otoliths are composed of calcium carbonate crystals condensed on a core protein lattice. Otoconin-90 (Oc90) is the major matrix protein of mammalian and avian otoconia, while otolith matrix protein (OMP) is the most abundant matrix protein found in the otoliths of teleost fish. We have identified a novel gene, otoc1, which encodes the zebrafish ortholog of Oc90. Expression of otoc1 was detected in the ear between 15 hpf and 72 hpf, and was restricted primarily to the macula and the developing epithelial pillars of the semicircular canals. Expression of otoc1 was also detected in epiphysis, optic stalk, midbrain, diencephalon, flexural organ, and spinal cord. During embryogenesis, expression of otoc1 mRNA preceded the appearance of omp-1 transcripts. Knockdown of otoc1 mRNA translation with antisense morpholinos produced a variety of aberrant otolith phenotypes. Our results suggest that Otoc1 may serve to nucleate calcium carbonate mineralization of aragonitic otoliths.

Keywords: Reissner's Substance, zebrafish, otoconin, Otoc1, otolith, matrix protein

Introduction

The vestibular system of the vertebrate inner ear conveys information about gravity and motion to the brain. Otolith organs are specialized components of the vestibular system that detect gravity and linear movements of the head through biomineralized particles coupled to the cilia of mechanosensory hair cells. Although the function of these vestibular structures is conserved among vertebrates, there are species-specific differences in their structural morphology. The biomineral particles of mammalian, avian, and amphibian vestibular systems are composed of thousands of tiny polyhedral particles called otoconia that are embedded in a gelatinous membrane. In contrast, teleost fish have three large otoliths that are smooth and ovoid in appearance.

Otoliths and otoconia are composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) crystals condensed around an extracellular matrix core composed of glycoproteins and proteoglycans (Ross and Peacor, 1975; Lim, 1980; Pote and Ross, 1991). It has been proposed that the polymorph of CaCO3 found in otoliths or otoconia is dependent on the matrix proteins comprising the extracellular core (Pote and Ross, 1991). Otoconin-90 (Oc90) is the predominant matrix protein found in calcitic CaCO3 otoconia of mammals and birds (Wang et al., 1998; Verpy et al., 1999), whereas Otoconin-22 (Oc22) is the primary matrix protein of aragonitic CaCO3 otoconia found in the saccule of amphibians (Pote et al., 1993). Oc90 and Oc22 share sequence homology with secretory phospholipase A2 (PLA2). Oc90 contains two PLA2-like (PLA2L) domains, while Oc22 has one. Although these PLA2L domains do not posses enzymatic activity, they are extremely acidic, contain several potential glycosylation sites, retain the ability to bind calcium, and provide a rigid structure that can serve as a scaffold for CaCO3 deposition (Pote et al., 1993; Wang et al., 1998; Thalmann et al., 2001). Gene targeting has recently been used to examine the role of Oc90 in mammalian otoconia formation (Zhao et al., 2007). Oc90 null mice fail to form the otoconial organic matrix, indicating that expression of Oc90 is necessary for the recruitment of other otoconins and organic components into the matrix core. Without formation of the organic matrix, the inorganic crystallites are prone to form large, disaggregated structures.

In teleost fish, otoliths grow diurnally and form daily rings within their aragonitic CaCO3 microstructure (Panella, 1971). Each ring is composed of a zone in which CaCO3 predominates and a discontinuous zone in which the organic matrix predominates (Degens et al., 1969). Three major otolith matrix proteins have been identified in teleost fish, OMP-1 (otolith matrix protein-1), Otolin-1, and Starmaker. OMP-1 is a mellanotransferin-like protein that is required for proper otolith growth and matrix formation (Murayama et al., 2000, 2005). OMP-1, like Oc90, is glycosylated, rich in cysteine residues, capable of binding calcium, and required for the recruitment of other proteins into the otolith organic matrix. Otolin-1, on the other hand, is required for the correct anchoring of otoliths on the sensory maculae and provides a collagenous scaffold that appears to stabilize the otolith matrix (Murayama et al., 2002, 2005). Starmaker is an ortholog of mammalian dentin sialo-phosphoprotein (DSPP), a protein that in humans is involved in the biomineralization of teeth (Sollner et al., 2003). In zebrafish, Starmaker appears to play an important role in controlling the morphology of the developing otolith. To date, however, there have been no otolith matrix proteins described in fish that posses PLA2L domains or that share sequence homology with either Oc90 or Oc22.

Here we have identified a novel gene, otoc1, which encodes the zebrafish ortholog of mammalian Oc90. Additional Oc90 orthologs were also identified in medaka and Xenopus. Each of these otoconins shares sequence conservation among their PLA2L domains. Zebrafish otoc1 is expressed in the ear from early somitogenesis through 72 hpf and becomes increasingly restricted to the macular region as development progresses. Expression of otoc1 was also detected in epiphysis, optic stalk, midbrain, diencephalon, flexural organ, and spinal cord. Knockdown of otoc1 mRNA translation with antisense morpholinos produced a variety of abnormal otolith phenotypes ranging from reduced size to complete absence. Coinjection of subeffective doses of otoc1 and omp-1 morpholinos produced a similar range of otolith defects. Our data indicate that Otoc1 is required for early events in otolith biomineralization and may be necessary for recruitment of other proteins into the organic matrix.

Materials And Methods

Cloning of Zebrafish otoc1 Gene

We carried out a Blast search of the zebrafish EST database and identified two ESTs [GenBank accession nos. BM182076 (fv53d08) and BM861236 (fy47e07)] that showed significant amino acid sequence similarity to the PLA2L domains of murine Oc90, and termed this novel gene otoc1. Because the two ESTs together failed to encompass the complete otoc1 open reading frame (ORF), we used RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) to generate the remaining otoc1 5′ mRNA sequence. RACE-ready cDNA was prepared from 24 hpf zebrafish embryos using the GeneRacer Kit (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). PCR was performed using the GeneRacer 5′ primer: 5′-CGACTG GAGCACGAGGACACTGA-3′, and otoc1-race primer: 5′-CTGCAGTTTCTCTCCTTTAGCTCTTGTGAACATCT CAAG-3′. cDNAs were sequenced using an ABI 377 automated DNA sequencer. Zebrafish otoc1 (GenBank accession no. AY826978) is a 3315-bp long cDNA containing a complete ORF that spans nucleotides 169–2988. Blast searches of the zebrafish genome assembly (Version Zv6) available from the Zebrafish Sequencing Group (http://www.ensembl.org/) were used to assign otoc1 to chromosome 2.

Human and chicken Oc90, as well as bullfrog Oc22, have previously been identified (NM_001080399, AAZ15113, and AB091830, respectively). Blast searches of available cDNA and genomic databases identified Oc90 orthologs in medaka (BJ010323, partial sequence) and X. tropicalis (BX738908, BX729352, BX708116, CX380335), while Oc22 orthologs were identified in X. tropicalis (CN085057, CN085058, CN076276, and CN076275) and X. laevis (BC078486).

Phylogenetic Analysis

Amino acid sequences of 31 PLA2 domains from PLA2 families I, II, V, and X, snake venom components, and otoconins were aligned using the PILEUP program (Devereux et al., 1984). Because of differences in spacing between conserved cysteines, alignments were unambiguous only at the 50 positions corresponding to amino acids 44–77 and 113–128 of human PLA2G1B (NP_000919). Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the Phylip suite of programs (version 3.573c) described by Felsenstein (1981). Maximum parsimony trees were calculated using PROTPARS. Evolutionary distance trees were constructed by using the algorithm of Fitch and Margoliash (1967). For each method, tree reliability was estimated by analysis of 100 half jackknife subreplicates. Since relationships between clusters of PLA2 domains were poorly supported in the bootstrap analysis, only the PLA2 domains of otoconins are shown in the resulting tree.

otoc1 mRNA Expression

Whole-mount in situ hybridization analysis was performed as described previously (Thisse and Thisse, 1998). The otoc1 antisense probe was generated from an otoc1 EST [GenBank accession no. BM182076 (fv53d08)]. Additional antisense RNA probes used in this study include pax2a (from I. Dawid), otx1 (from E. Weinberg), dlx3b (Ekker et al., 1992a), and msxC (Ekker et al., 1992b).

For RT-PCR analysis, zebrafish embryos at various stages of development, as well as 6-month-old adults, were collected and homogenized in TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). Total RNA was extracted according to the method of Chomczynski and Sacchi (1987), and 0.5 μg of RNA was used as template to generate cDNA (SuperScript First Strand Synthesis kit; Invitrogen). For all samples, PCR was performed with REDTaq DNA polymerase (Sigma; St. Louis, MO), 1 μg of cDNA, and primers specific for otoc1 (5′-CCAGCCAGCGCAGGTATGTGTA-3′ and 5′-GCGGCTGAGGAAACTCGAAGATC-3′) or omp-1 (5′-GCTACC TTCTGAGGAATAAGCTGG-3′ and 5′-CTTGATGTCCC CACACACAGGC-3′). PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.5%-agarose gel, and imaged with a Fluorochem 8900 imaging system (Alpha Innotech; San Leandro, CA). The identity of the PCR products from each primer pair was verified by DNA sequencing.

Antisense Morpholinos

Antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) (Gene Tools LLC; Philomath,OR) were targeted against either the initiating methionine [otoc1-ATG MO (5′-GAAAATAAGAT ACAGCATCCTCATC-3′)], or the donor splice site of intron 4 [otoc1-SS MO (5′-TCCGCTTCATCTCACCCG TCGAGCG-3′)] of otoc1 mRNA. We also used an antisense morpholino targeted against the initiating methionine of omp-1 [omp-MO (5′-CAAGATGTCCTCCTGGAAGA TCCAT-3′)]. This MO was generously provided by Dr. Ruediger Thalmann (Washington University, St. Louis). MOs were resuspended in 1× Danieau buffer (58 mM NaCl, 0.7 mM KCl, 0.4 mM MgSO4, 0.6 mM Ca(NO3)2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.6), and microinjected directly into the yolk sac of single cell embryos. The ability of the otoc1 morpholino to specifically block translation of otoc1 mRNA was tested using an in vitro translation assay as previously described (Blasiole et al., 2005, 2006).

Immunofluorescence Analysis of Tether Cells

We visualized tether cells by immunostaining with antibody to acetylated tubulin as described previously (Riley et al., 1999; Millimaki et al., 2007). The primary antibody was acetylated tubulin (Sigma T-6793, diluted 1:100), while the secondary antibody was Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes A-11001, diluted 1:50). Tether cell kinocilia were compared between control and morphant ears using compound fluorescence microscopy. Hair cell bodies were detected using a transgenic zebrafish line expressing membrane-targeted GFP under control of the brn3c promoter/enhancer (Xiao et al., 2005). This fish strain was kindly provided by Herwig Baier (UCSF).

Results

Identification of otoc1

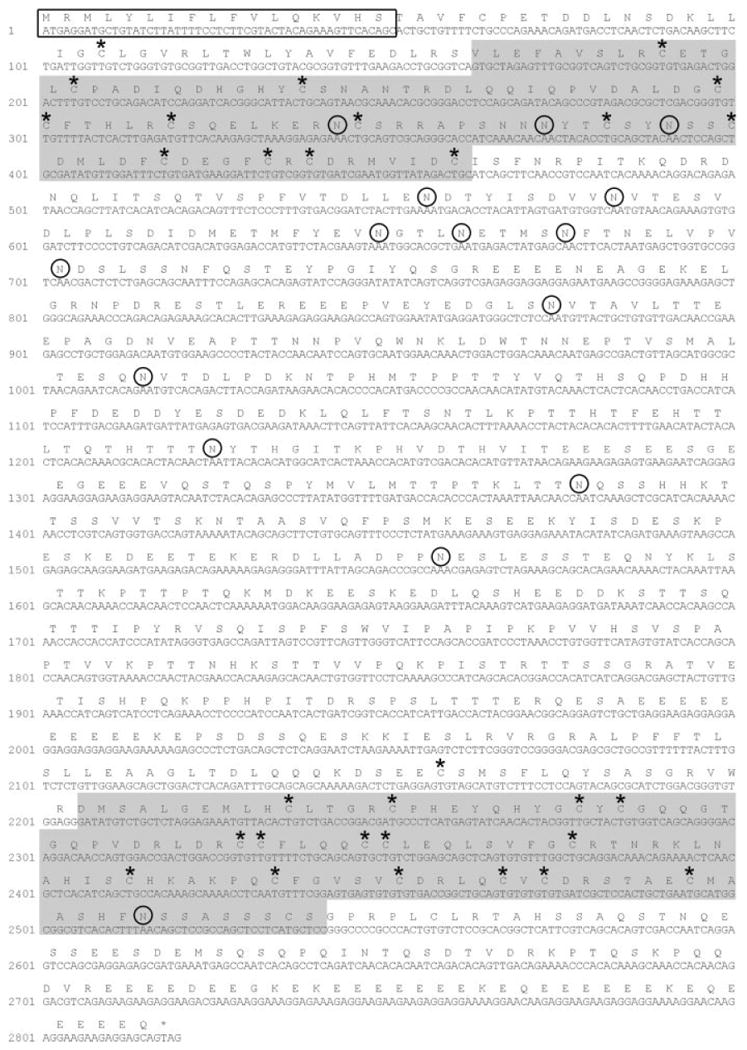

We carried out a Blast search of the zebrafish EST database and identified two ESTs [GenBank accession nos. BM182076 (fv53d08) and BM861236 (fy47e07)] that showed significant amino acid sequence similarity to the PLA2L domains of murine Oc90. We named this previously unidentified gene otoc1. Although the two ESTs overlapped, together they failed to encompass the complete otoc1 open reading frame (ORF). We therefore used 5′ RACE to generate the full-length otoc1 coding sequence. The complete cDNA and deduced amino acid sequence for zebrafish otoc1 is shown in Figure 1. The zebrafish otoc1 gene (GenBank accession no. AY826978) consists of a 2820-base pair ORF encoding a polypeptide of 939 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 106 kDa. Blast searches of the zebrafish genome assembly available from the Zebrafish Sequencing Group (http://www.ensembl.org/) indicate that otoc1 maps to chromosome 2.

Figure 1.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of zebrafish otoc1. The predicted secretory signal sequence is boxed, and the two PLA2L domains are shaded in gray. Circles indicate potential glycosylation sites and asterisks designate the location of conserved cysteines. Nucleotides are numbered with 1 representing the A of the initiating methionine.

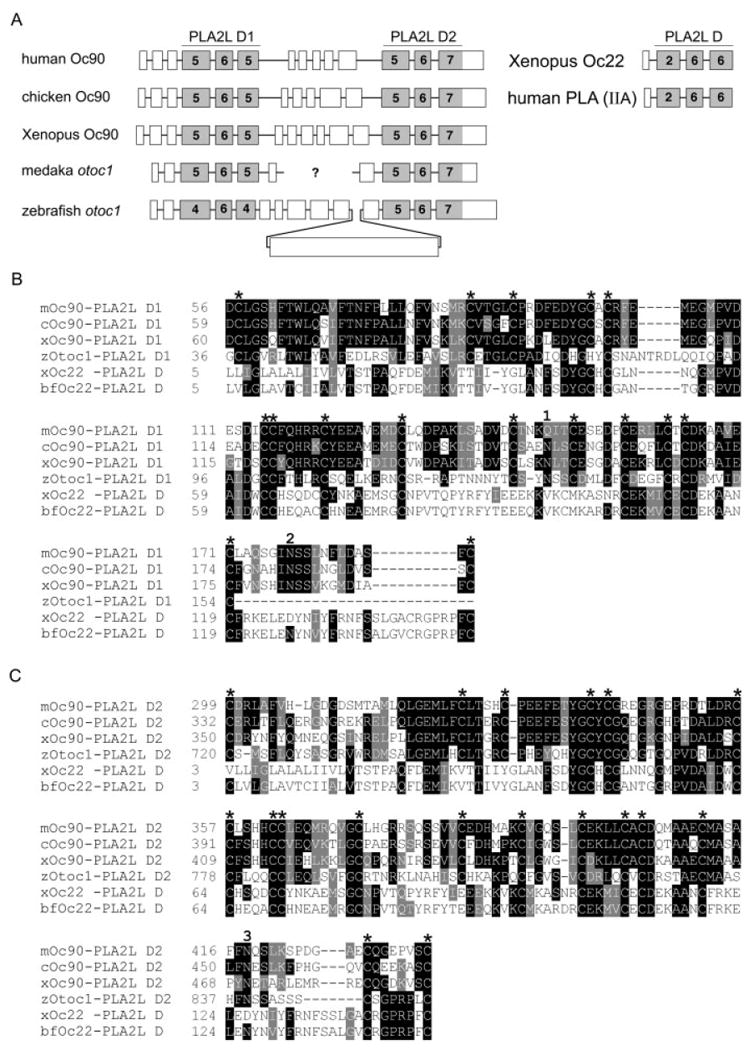

Blast searches of available cDNA and genomic databases identified Oc90 orthologs in additional fish species, including medaka. Surprisingly, both Oc22 and Oc90 transcripts were identified in Xenopus. A comparison of the gene structure for representative Oc90 and Oc22 orthologs is presented in Figure 2(A). The genes share the greatest degree of sequence and structural similarity within the two PLA2L domains [Fig. 2(A–C)] and the N-terminal secretory peptide.

Figure 2.

Comparison of otoconin orthologs. (A) Exon/intron organization of human, chicken, Xenopus tropicalis, medaka, and zebrafish Oc90 orthologs are shown to the left. X. tropicalis Oc22 and human PLA2 (Type IIA) genes are on the right. Exons are represented by open boxes drawn to scale. Introns (lines connecting exons) are not drawn to scale. PLA2L domains are shaded in gray. Numbers in shaded boxes denote the number of cysteines. A full-length sequence for medaka otoc1 is not currently available. Question mark in the medaka gene represents a gap in the known sequence. (B) Amino acid alignment of first PLA2L domain of Oc90 orthologs from mouse (m), chicken (c), X. tropicalis (x), and zebrafish (z) and the single PLA2L domain from bullfrog (bf) and X. tropicalis Oc22. (C) Amino acid alignment of the second PLA2L domain of Oc90 orthologs from mouse, chicken, X. tropicalis, and zebrafish, and the single PLA2L domain from bullfrog and X. tropicalis Oc22. Identical amino acids are highlighted in black, and conserved amino acids are highlighted in gray. Amino acids are numbered to the left. Asterisks indicate cysteine residues, and numbers above sequence indicate potential conserved sites of N-linked glycosylation.

It has been proposed that the structural rigidity of the PLA2L domains within otoconin proteins facilitates the formation of the organic otolith matrix (Thalmann et al., 2001). This rigidity results from the disulfide bonds formed between cysteine residues. The number of cysteine residues within exons encoding the PLA2L domains of OTOC1 and each of its orthologs is shown in Figure 2(A). Zebrafish OTOC1 contains two fewer cysteines within the first PLA2L domain compared with other Oc90 orthologs. As shown in Figures 1 and 2(B,C), the position of the cysteine residues within otoconin PLA2L domains is highly conserved across species.

A comparison of the molecular weight, predicted pI, and number of potential N-linked glycosylation sites for Otoc1 and other otoconins is presented in Table 1. The predicted pI for Oc90 orthologs ranges from a pH of 4.53–4.94, with zebrafish OTOC1 being the most acidic. Amongst otoconin family members there is a high degree of variability in the number of potential N-linked glycosylation sites. For example, there are only two potential N-linked glycosylation sites within human Oc90, while zebrafish Otoc1 contains 15 potential N-linked glycosylation sites (Fig. 1). Only three of the potential N-linked glycosylation sites are conserved between otoconin family members [Fig. 2(B,C)].

Table 1. Comparison of PLA2L Otoconins.

| Otoconin | Predicted MW | Predicted pI | Predicted N-linked Gly Sites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Oc90 | 51.73 | 4.73 | 2 |

| Mouse Oc90 | 52.44 | 4.72 | 4 |

| Chicken Oc90 | 57.73 | 4.94 | 4 |

| Xenopus Oc90 | 59.76 | 4.73 | 5 |

| Zebrafish Otoc1 | 105.97 | 4.53 | 15 |

| Xenopus Oc22 | 16.69 | 6.69 | 2 |

| Bullfrog Oc22 | 16.60 | 6.29 | 2 |

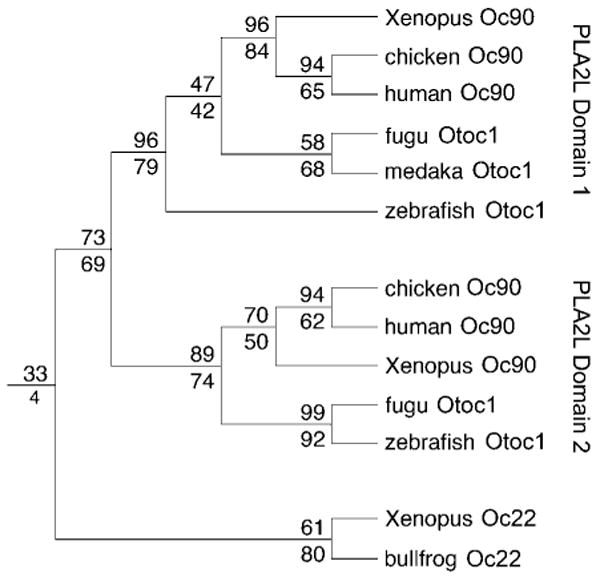

Phylogenetic Analysis

To confirm the evolutionary relationship between zebrafish OTOC1 and its mammalian, avian, and amphibian orthologs, we conducted a phylogenetic analysis using maximum parsimony (MP) (Felsenstein, 1981) and distance matrix (DM) (Fitch and Margoliash, 1967) methods (Fig. 3) using 13 otoconin PLA2L domains and 18 additional PLA2 sequences. The PLA2L domains of Otoc1 and its Oc90 orthologs cluster together in 73% (DM) and 69% (MP) of trees generated by bootstrap analysis, and clustering by position within the polypeptide is even more strongly supported, with the first domain clustering in 96% (DM) and 79% (MP), and the second domain in 89% (DM) and 74% (MP) of all trees. Clustering of Oc22 orthologs is also strongly supported by 61% (DM) and 80% (MP) of trees. In contrast, clustering of Oc90 with Oc22 is poorly supported (33% by DM and only 4% by MP).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of PLA2L otoconins. The tree was rooted using 18 additional PLA2 sequences, including the seven alignable human PLA2 sequences from groups I, II, V, and X. Numbers to the left of each node indicate percent support from bootstrap analysis (Fitch/Margoliash above, maximum parsimony below). Consensus trees obtained from both methods agree, except that the grouping of all otoconin domains was supported by only 4% of trees in the MP analysis. Alternative clusterings using the MP method were supported by no more than 15% of trees.

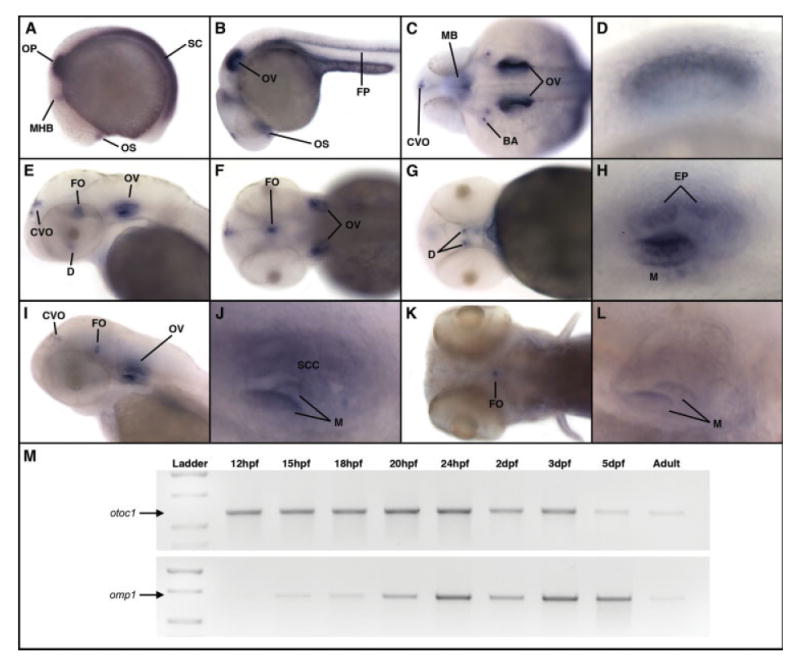

Expression of otoc1 mRNA

We used whole-mount in situ hybridization to examine otoc1 mRNA expression during zebrafish embryogenesis. The expression profiles of zebrafish otoc1 are shown in Figure 4. Expression of the otoc1 gene was detected as early as 15 hpf in the otic vesicle, midbrain-hindbrain boundary, optic stalk, and spinal cord [Fig. 4(A)]. Expression of otoc1 in these tissues persisted at 24 hpf, although otoc1 transcripts in the spinal cord became restricted to the floor plate [Fig. 4(B,C)]. At 24 hpf, otoc1 transcripts were also detected in the region of the circumventricular organs and developing branchial arches. In the ear at 24 hpf, otoc1 expression was detected throughout the otic vesicle except for a ventral portion of the epithelium [Fig. 4(D)]. At 48 hpf, otoc1 mRNA was present in the diencephalon, flexural organ, circumventricular region, and the otic vesicle [Fig. 4(E–H)]. In the otic vesicle, expression of otoc1 was predominant in the macular regions, with lighter staining also observed in the epithelial protrusions of the developing semicircular canals [Fig. 4(H)]. A similar expression pattern of otoc1 mRNA was observed at 72 hpf, although staining was less intense throughout the embryo and absent from the diencephalon [Fig. 4(I,J)]. By 5 dpf, only very low levels of otoc1 mRNA were detected and were localized predominantly in the flexural organ [Fig. 4(K,L)]. Virtually no transcripts were detectable in the ear at 5 dpf.

Figure 4.

Expression of zebrafish otoc1 mRNA during embryogenesis. Expression of otoc1 was analyzed by whole-mount in situ hybridization (A–L). (A) Early somitogenesis, lateral view, (B) 24 hpf, lateral view, (C) 24 hpf, dorsal view, (D) 24 hpf, lateral view of ear, (E) 48 hpf, lateral view of head, (F) 48 hpf, dorsal view of head, (G) 48 hpf, ventral view of head, (H) 48 hpf, lateral view of ear, (I) 72 hpf, lateral view of head, (J) 72 hpf, lateral view of ear, (K) 5 dpf, dorsal view of head, (L) 5 dpf, lateral view of ear. BA, branchial arches; CVO, circumventricular organs; D, diencephalon; EP, epithelial protrusions of developing semicircular canals; FO, flexural organ; FP, floor plate; M, macula; MB, midbrain; MHB, midbrain/hindbrain boundary; OP, otic placode; OS, optic stalk; OV, otic vesicle; PF, pectoral fin; SC, spinal cord; SCC, semicircular canal pillars. (M) Comparison of otoc1 and omp-1 mRNA expression during zebrafish development determined by RT-PCR. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

We next used RT-PCR to compare the temporal expression of otoc1 and omp-1, the major matrix protein of teleost otoliths. As shown in Figure 4(M), primers specific for otoc1 amplified a product in all developmental stages analyzed from 12 hpf through adult. Although the PCR we performed was not quantitative, otoc1 amplicons generated from 5 dpf and adult were consistently (n = 4) less intense than amplicons generated from earlier developmental stages, suggesting that levels of otoc1 transcripts may decrease during the course of development. These results are consistent with our in situ hybridization data which showed decreasing levels of otoc1 mRNA staining as a function of developmental age. In contrast, omp-1 expression was first detected at 15 hpf and persisted throughout embryogenesis including 5 dpf embryos (Murayama et al., 2005). Lower levels of omp-1 PCR products were observed at 15 and 18 hpf compared with larval stages. As was the case with otoc1, omp-1 expression levels were consistently lower in the adult (n = 4) compared with embryonic stages. These results suggest that expression of otoc1 precedes that of omp-1, raising the possibility that Otoc1 may be required for initiating formation of the organic matrix of zebrafish otoliths.

Morpholino Knockdown of otoc1 mRNA Translation

To gain an understanding of the function of otoc1, we used antisense morpholinos (MOs) to knock down otoc1 mRNA translation in developing zebrafish embryos. Two nonoverlapping MOs were generated that targeted either the initiating methionine (otoc1-ATG MO), or the donor splice site of intron 4 (otoc1-SS MO) of zebrafish otoc1 mRNA. Using an in vitro translation assay (Blasiole et al., 2005, 2006), the otoc1-ATG MO was found to specifically block expression of otoc1 mRNA in a dose-dependent fashion (data not shown).

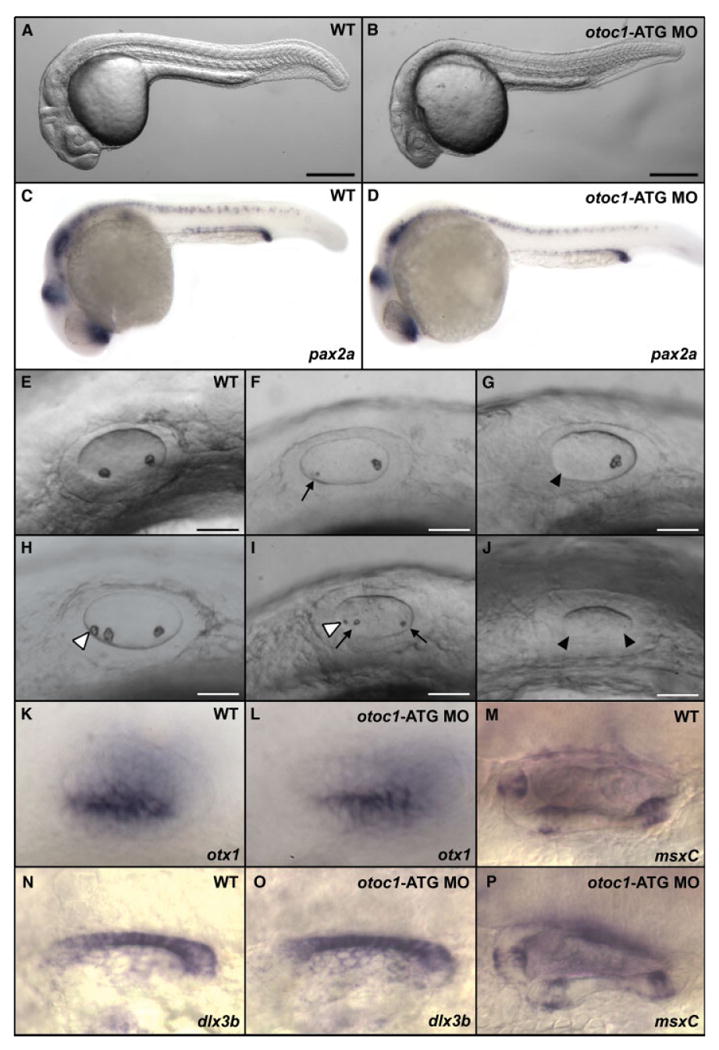

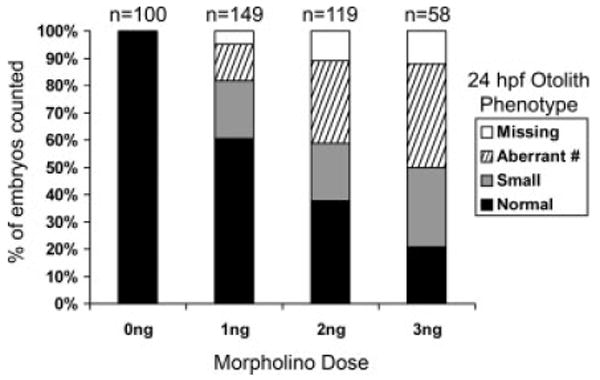

otoc1-ATG MO and otoc1-SS MO were separately microinjected into one-cell stage embryos. Microinjection of the otoc1-ATG MO (at doses ranging from 1 to 3 ng) into zebrafish embryos produced noticeable effects on ear development, whereas embryos injected with Danieau buffer alone showed no defects. At 24 hpf, morphant embryos appeared to develop normally, although morphants exhibited a slightly diminished head size compared with wild-type embryos [Fig. 5(A,B)]. Injection of the otoc1-ATG MO induced a number of aberrant otolith phenotypes [Fig. 5(F–J)]. These defects ranged in severity and included small otoliths [Fig. 5(F,I)], extra or missing otoliths [Fig. 5(G–I)], or complete absence of otoliths [Fig. 5(J)]. The percentage of fish displaying aberrant otoliths increased with increasing doses of MO (Fig. 6). At 1 ng, 40% exhibited otolith defects while at 3 ng MO, 80% showed defects in otolith formation. The severity of the otolith defect also increased as a function of increased MO concentration. For example at a 1 ng dose of MO, 5% of the fish had no otoliths, whereas at a dose of 3 ng, 12% had no otoliths (Fig. 6). Injection of the otoc1-SS MO failed to phenocopy the otolith defects produced by the otoc1-ATG MO, and was extremely toxic even at low concentrations. Morphants that displayed small or additional otoliths at 24 hpf appeared to recover and exhibited two normal-sized otoliths by 48 hpf. However, otoc1 morphants that failed to develop otoliths or formed only one otolith by 24 hpf continued to display a similar phenotype at 48 hpf.

Figure 5.

Expression of otoc1 is necessary for normal otolith development. Panels A–K, N, and L show a lateral view of embryos at 24 hpf with anterior to the left. Morphants were injected with 2 ng of otoc1-ATG MO. (A) Wild type embryo, (B) otoc1 morphant, (C, D) pax2a staining of (C) wild type embryo, (D) otoc1 morphant, (E) otic vesicle, wild type embryo, (F–J) otic vesicle, otoc1 morphants, (K,L) otx1 staining of (K) wild type otic vesicle. (L) otoc1 morphant otic vesicle. (N, O) dlx3b staining of (N) wild type otic vesicle (O) otoc1 morphant otic vesicle. (M–P) msxC staining at 60 hpf of (M) wild type otic vesicle (P) otoc1 morphant otic vesicle. Arrows indicate small otoliths, black arrowheads indicate missing otoliths, while white arrowheads indicate extra otoliths. Scale bars: A–B, 250 μm; E–J, 50 μm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Figure 6.

Phenotypes of otoc1 morphants. Bar graph depicts percent of fish at 24 hpf that displayed normal otoliths, small otoliths, aberrant number of otoliths, and complete lack of otoliths when injected with various doses of otoc1-ATG MO. The number of fish assayed at each dose of MO is displayed above the bars.

It is possible that the otolith defects in otoc1 morphants reflect a general developmental delay. To address this possibility, we used pax2a, otx1, dlx3b, and msxC to analyze development of a variety of organ systems. In zebrafish, pax2a is commonly used as a marker for normal embryonic development (Shu et al., 2003; Blasiole et al., 2005), while otx1, dlx3b, and msxC were used as markers for correct patterning of the ear (Ekker et al., 1992a,b; Hammond et al., 2003). As shown in Figure 5, the expression patterns of pax2a, otx1, and dlx3b in 24 hpf morphants, and msxC in 60 hpf morphants, closely resembled that of wild-type embryos. These results suggest that embryos treated with otoc1-ATG MOs develop normally during early embryogenesis.

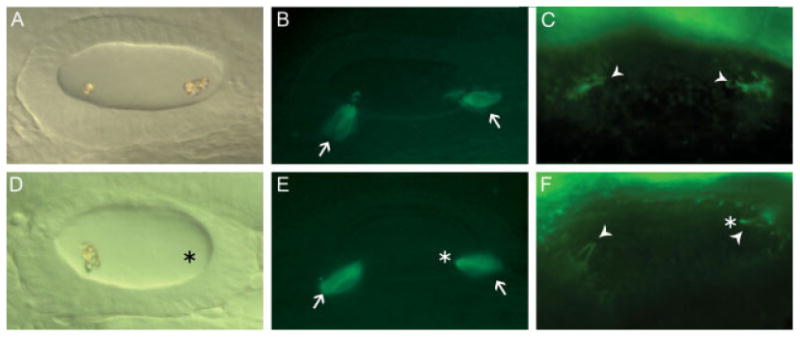

Tether cells are precocious hair cells that are essential for otolith seeding (Riley et al., 1997). To determine whether knockdown of otoc1 expression caused defects in tether cell development, we visualized tether cells in GFP-expressing transgenic fish (Xiao et al., 2005), and by immunostaining with antibody to acetylated tubulin. Tether cell kinocilia and cell bodies were compared between control and morphant ears, as shown in Figure 7. We observed intact tether cell bodies (16/16 morphants) and tether cell kinocilia in wild type and otoc1 morphants (15/15 morphants). Taken together, these results suggest that the otolith defects observed in otoc1 morphants are not because of the absence of tether cell bodies or kinocilia.

Figure 7.

Tether cells are present in otoc1 morphant ears. All panels show a lateral view of embryos at 24 hpf with anterior to the left. (A, D) DIC images of (A) wild type otic vesicle (D) otoc1 morphant otic vesicle containing only one otolith. Fluorescent image of (B) wild type otic vesicle from GFP-expressing Brn3c transgenic fish (E) otoc1 morphant otic vesicle from GFP-expressing Brn3c transgenic fish. A pair of tether cells (arrows) is present at the anterior and posterior poles. Anti-acetylated tubulin immunofluorescence of tether cell kinocilia in (C) wild type otic vesicle and (F) otoc1 morphant otic vesicle. Arrowheads indicate a pair of tether cell kinocilia at the anterior and posterior poles of the otic vesicle. Asterisks indicate position of missing otolith. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

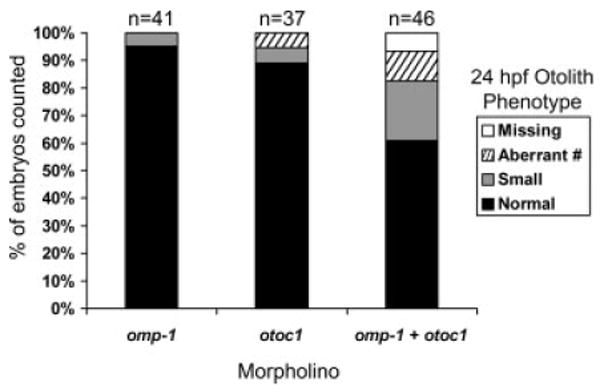

Morpholinos targeted against omp-1 have previously been shown to produce morphant fish with small otoliths (Murayama et al., 2005). Amongst the otolith phenotypes produced by knockdown of otoc1 were morphants with small otoliths, suggesting a possible functional interaction between otoc1 and omp-1. To test this idea, we coinjected subeffective doses of otoc1-ATG MO (0.5 ng) and omp-1 MO (0.5 ng) and analyzed the effect on otolith development. At a concentration of 0.5 ng, neither the otoc1 MO (n = 37) nor the omp-1 MO (n = 41) produced severe otolith development defects, although 5–10% of fish displayed minor defects such as reduced otolith size and appearance of extra otolith particles. However, coinjection of subeffective doses of the two MOs produced an otolith defect in 39% of the embryos (n = 46) with 6.5% exhibiting loss of both otoliths (Fig. 8). Coinjection of the two MOs thus appears to amplify the otolith defects observed when either otoc1 or omp-1 MOs is used alone. The functional interaction observed in this assay suggests that otoc1 and omp-1 may act synergistically in formation of the organic matrix early in otolith development.

Figure 8.

Phenotypes of embryos coinjected with subeffective doses of otoc1-ATG and omp-1 morpholinos. Bar graph depicts percent of fish at 24 hpf that displayed normal otoliths, small otoliths, aberrant number of otoliths, and complete lack of otoliths when injected with 0.5 ng of either otoc1-ATG MO alone, omp-1 MO alone, or 0.5 ng of otoc1-ATG MO plus 0.5 ng of omp-1 MO. The number of fish assayed for each treatment is displayed above the bars.

Discussion

We have identified a novel gene, otoc1, which encodes a zebrafish otolith matrix protein. Otoc1 is orthologous to Oc90, the major matrix protein of mammalian otoconia. Orthologs of Oc90 are also present in the genomes of medaka and Xenopus. Although otolith matrix proteins containing PLA2L structural domains have not previously been described in teleost fish, Otoc1 contains two PLA2L domains and shares sequence homology with Oc90 orthologs primarily within these regions of the protein. Identification of otoc1 in zebrafish is somewhat surprising, since it has generally been assumed that variations in the CaCO3 polymorph characteristic of mammalian, amphibian, or fish ear stones are dependent on differences in the protein species comprising the organic matrix core. Previous studies have implicated Oc90 as the predominant matrix protein of calcitic otoconia, and OMP as the predominant protein of aragonitic otoliths. The identification of zebrafish otoc1 therefore suggests that Oc90 orthologs may be necessary, but not sufficient, for formation of calcitic otoconia.

Besides containing nonfunctional PLA2L domains, Otoc1 shares a number of other structural features with otoconin family members. Each of these core matrix proteins appears to be a glycoprotein, and each is characterized by having an acidic pI that presumably aids in calcium binding. Otoc1 and Oc90 orthologs also share a cysteine-rich composition that may allow for the formation of multiple disulfide bridges. The fact that there is a high degree of conservation in the number and location of cysteines within the PLA2L domains of otoconin family members suggests that the formation of disulfide bridges may be important in building the rigid backbone of the otolith protein matrix and may act to form a scaffold for accretion of CaCO3 crystals.

Three major otolith matrix proteins, Starmaker (Sollner et al., 2003), OMP-1 (Murayama et al., 2000, 2005), and Otolin-1 (Murayama et al., 2002, 2005), have been described to date in teleost fish. In zebrafish, the functional role of these proteins in early otolith development has been deduced by using antisense morpholinos to knock down translation of the cognate mRNAs. Morpholino-mediated knock down of starmaker expression causes a delay in otolith formation as well as a change in the crystal polymorph of otoliths from aragonite to calcite, suggesting that Starmaker function is required for maintaining proper otolith morphology (Sollner et al., 2004). OMP-1 appears to be the predominant otolith matrix protein of teleost fish (Murayama et al., 2000). In zebrafish, OMP-1 morphants initiate otolith development, but the otoliths fail to reach normal size, suggesting that OMP-1 is required for proper otolith growth (Murayama et al., 2005). In contrast, knockdown of otolin-1 mRNA expression produces a very different phenotype. Morphant otoliths lose adherence to the sensory maculae and fuse, suggesting that Otolin-1 is required for the correct anchoring of the otoliths on the sensory maculae (Murayama et al., 2005).

Otoc1 represents the fourth otolith matrix protein to be identified in teleost fish. Overall, the effect of knocking down otoc1 mRNA expression on otolith development is more severe than the morphant phenotypes produced by knocking down OMP-1 expression. The predominant phenotype of OMP-1 morphants is small otoliths (Murayama et al., 2005). In contrast, otoc1 morphants exhibit a variety of otolith defects including small otoliths, extra or missing otoliths, and in some cases complete absence of otoliths. These phenotypic differences suggest that Otoc1 may function upstream of OMP-1 during otolith development. Interestingly, our in situ hybridization analysis of otoc1 mRNA expression revealed the presence of otoc-1 mRNA transcripts as early as 15 hpf (15 hpf being the earliest stage analyzed), while previous studies reported OMP-1 mRNA expression beginning at 16 hpf (Murayama et al., 2005). By using RT-PCR, otoc-1 mRNA expression was clearly detectable at 12 hpf, whereas OMP-1 amplicons were not visualized until 15 hpf. These results suggest that expression of otoc1 mRNA precedes that of omp-1. The availability of antibodies against zebrafish Otoc1 will clearly be necessary to compare the temporal pattern of Otoc-1 protein expression with that of OMP-1. However, our results suggest the possibility that Otoc-1 may be required for the initial steps in formation of the organic matrix of zebrafish otoliths, and for the recruitment of other otoconins into the matrix core. Evidence for a functional interaction between Otoc-1 and OMP-1 (i.e., otolith defects produced by coinjection of subeffective doses of otoc1 and omp-1 MOs) is consistent with this hypothesis.

During early embryogenesis in zebrafish, the otic vesicle represents the predominant expression site of the otoc1 gene. However, otoc1 transcripts were also detected in several peripheral tissues including floor plate, circumventricular organs, and the flexural organ. Interestingly, these anatomical sites of otoc1 expression coincide almost exactly with the expression of Reissner's substance (Lichtenfeld et al., 1999; Lehmann and Naumann, 2005). Reissner's substance is a mixture of glycoproteins, including SCO-spondin (also called Reissner's Fibre - Gly1) (Herrera and Rodriguez, 1990; Karoumi et al., 1990; Nualart et al., 1991, 1998; Gobron et al., 1996; Didier et al., 2000; Lehmann et al., 2001; Meiniel, 2001), that are secreted from the floor plate, flexural organ, and subcommissural organ (SCO) in zebrafish and other vertebrate species. Reissner's substance is secreted by cells of the SCO into the ventricle where it aggregates into a threadlike structure called Reissner's fibre, which extends the entire length of the central canal of the spinal cord. Reissner's substance is also produced by cells in the floor plate and flexural organ. Analysis of the zebrafish mutants cyclops and one-eyed pinhead suggest that Reissner's substance may play a role in axonal guidance and commissure formation (Lehmann and Naumann, 2005). The predicted structural features of Otoc1 (rigid backbone and multiple sites for addition of N-linked sugars) suggest that Otoc1 may serve as a scaffold for deposition of the glycoprotein components of this fibrous complex. However, no apparent morphological defects were detected in brain structures of otoc1 morphants, and in this study, axon guidance was not analyzed. It will be of considerable interest to learn whether the otoc1 gene product, in addition to its role in otolith development, is a component of Reissner's substance. Although speculative, this hypothesis can also be tested using Otoc1-specific antibodies to analyze Otoc1 expression in the zebrafish mutants cyclops and one-eyed pinhead that lack a floor plate and show altered deposition of Reissner's substance.

The biomineralization of ear stones in the inner ear is a highly regulated process that requires that organic and inorganic components be brought together in the proper temporospatial context. The initial step in this process involves formation of an organic matrix which serves as a scaffold upon which CaCO3 crystals can seed and grow. Morphant phenotypes produced by injecting otoc1 MOs suggest that otoc1 expression is required for otolith development and may serve as a scaffold for recruitment of other otoconins into the organic matrix.

The identification of otoc1 has led us to propose a new model of normal otolith development in zebrafish in which Otoc1 initiates otolith seeding while OMP is required for otolith growth. This hypothesis can be tested by comparing Otoc1 and Omp-1 protein distribution in the inner ear of wild type and otoc1 morphant embryos using antibodies specific for each of these proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. R. Thalmann and I. Thalmann (Washington University, St. Louis) for their continued support and advice, Joe Bednarczyk of the Molecular Genetics Core Facility, Penn State College of Medicine, for DNA sequencing, and Herwig Baier (UCSF) for the Brn3c transgenic fish line.

Contract grant sponsor: National Institute of Mental Health; contract grant number: MH-068789.

Contract grant sponsor: Pennsylvania Department of Health (Tobacco Settlement Funds).

References

- Blasiole B, Canfield VA, Vollrath MA, Huss D, Mohideen MA, Dickman JD, Cheng KC, et al. Separate Na, K-ATPase genes are required for otolith formation and semicircular canal development in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2006;294:148–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasiole B, Kabbani N, Boehmler W, Thisse B, Thisse C, Canfield V, Levenson R. Neuronal calcium sensor-1 gene ncs-1a is essential for semicircular canal formation in zebrafish inner ear. J Neurobiol. 2005;64:285–297. doi: 10.1002/neu.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degens ET, Deuser WG, Haedrich RL. Molecular structure and composition of fish otoliths. Mar Biol. 1969;2:105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didier R, Creveaux I, Meiniel R, Herbet A, Dastugue B, Meiniel A. SCO-spondin and RF-GlyI: Two designations for the same glycoprotein secreted by the subcommissural organ. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:500–507. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000901)61:5<500::AID-JNR4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekker M, Akimenko MA, Bremiller R, Westerfield M. Regional expression of three homeobox transcripts in the inner ear of zebrafish embryos. Neuron. 1992a;9:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekker SC, von Kessler DP, Beachy PA. Differential DNA sequence recognition is a determinant of specificity in homeotic gene action. EMBO J. 1992b;11:4059–4072. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: A maximum likelihood approach. J Mol Evol. 1981;17:368–376. doi: 10.1007/BF01734359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch WM, Margoliash E. Construction of phylogenetic trees. Science. 1967;155:279–284. doi: 10.1126/science.155.3760.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobron S, Monnerie H, Meiniel R, Creveaux I, Lehmann W, Lamalle D, Dastugue B, et al. SCO-spondin: A new member of the thrombospondin family secreted by the subcommissural organ is a candidate in the modulation of neuronal aggregation. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Part 5):1053–1061. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.5.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond KL, Loynes HE, Folarin AA, Smith J, Whitfield TT. Hedgehog signalling is required for correct anteroposterior patterning of the zebrafish otic vesicle. Development. 2003;130:1403–1417. doi: 10.1242/dev.00360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera H, Rodriguez EM. Secretory glycoproteins of the rat subcommissural organ are N-linked complex-type glycoproteins. Demonstration by combined use of lectins and specific glycosidases, and by the administration of Tunicamycin. Histochemistry. 1990;93:607–615. doi: 10.1007/BF00272203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karoumi A, Meiniel R, Croisille Y, Belin MF, Meiniel A. Glycoprotein synthesis in the subcommissural organ of the chick embryo. I. An ontogenetical study using specific antibodies. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1990;79:141–153. doi: 10.1007/BF01245126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann C, Naumann WW. Axon pathfinding and the floor plate factor Reissner's substance in wildtype, cyclops and one-eyed pinhead mutants of Danio rerio. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;154:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann W, Wagner U, Naumann WW. Multiple forms of glycoproteins in the secretory product of the bovine subcommissural organ—An ancient glial structure. Acta Histochem. 2001;103:99–112. doi: 10.1078/0065-1281-00583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenfeld J, Viehweg J, Schutzenmeister J, Naumann WW. Reissner's substance expressed as a transient pattern in vertebrate floor plate. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1999;200:161–174. doi: 10.1007/s004290050270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim DJ. Morphogenesis and malformation of otoconia: A review. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1980;16:111–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiniel A. SCO-spondin, a glycoprotein of the subcommissural organ/Reissner's fiber complex: Evidence of a potent activity on neuronal development in primary cell cultures. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;52:484–495. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20010301)52:5<484::AID-JEMT1034>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millimaki BB, Sweet EM, Dhason MS, Riley BB. Zebrafish atoh1 genes: Classic proneural activity in the inner ear and regulation by Fgf and Notch. Development. 2007;134:295–305. doi: 10.1242/dev.02734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama E, Herbomel P, Kawakami A, Takeda H, Nagasawa H. Otolith matrix proteins OMP-1 and Otolin-1 are necessary for normal otolith growth and their correct anchoring onto the sensory maculae. Mech Dev. 2005;122:791–803. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama E, Okuno A, Ohira T, Takagi Y, Nagasawa H. Molecular cloning and expression of an otolith matrix protein cDNA from the rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;126:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(00)00223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama E, Takagi Y, Ohira T, Davis JG, Greene MI, Nagasawa H. Fish otolith contains a unique structural protein, otolin-1. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:688–696. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nualart F, Hein S, Rodriguez EM, Oksche A. Identification and partial characterization of the secretory glycoproteins of the bovine subcommissural organ-Reissner's fiber complex. Evidence for the existence of two precursor forms. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1991;11:227–238. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(91)90031-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nualart F, Hein S, Yulis CR, Zarraga AM, Araya A, Rodriguez EM. Partial sequencing of Reissner's fiber glycoprotein I (RF-Gly I) Cell Tissue Res. 1998;292:239–250. doi: 10.1007/s004410051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panella G. Fish otoliths: Daily growth layers and periodical patterns. Science. 1971;170:1124–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.173.4002.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pote KG, Hauer CR, III, Michel H, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Kretsinger RH. Otoconin-22, the major protein of aragonitic frog otoconia, is a homolog of phospholipase A2. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5017–5024. doi: 10.1021/bi00070a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pote KG, Ross MD. Each otoconia polymorph has a protein unique to that polymorph. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1991;98:287–295. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(91)90181-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley BB, Chiang M, Farmer L, Heck R. The deltaA gene of zebrafish mediates lateral inhibition of hair cells in the inner ear and is regulated by pax2.1. Development. 1999;126:5669–5678. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley BB, Zhu C, Janetopoulos C, Aufderheide KJ. A critical period of ear development controlled by distinct populations of ciliated cells in the zebrafish. Dev Biol. 1997;191:191–201. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MD, Peacor DR. The nature and crystal growth of otoconia in the rat. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1975;84:22–36. doi: 10.1177/000348947508400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu X, Cheng K, Patel N, Chen F, Joseph E, Tsai HJ, Chen JN. Na, K-ATPase is essential for embryonic heart development in the zebrafish. Development. 2003;130:6165–6173. doi: 10.1242/dev.00844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollner C, Burghammer M, Busch-Nentwich E, Berger J, Schwarz H, Riekel C, Nicolson T. Control of crystal size and lattice formation by starmaker in otolith biomineralization. Science. 2003;302:282–286. doi: 10.1126/science.1088443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollner C, Schwarz H, Geisler R, Nicolson T. Mutated otopetrin 1 affects the genesis of otoliths and the localization of Starmaker in zebrafish. Dev Genes Evol. 2004;214:582–590. doi: 10.1007/s00427-004-0440-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thalmann R, Ignatova E, Kachar B, Ornitz DM, Thalmann I. Development and maintenance of otoconia: Biochemical considerations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;942:162–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C, Thisse B. High resolution whole-mount in situ hybridization. Zebrafish Sci Monit. 1998;5:8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Verpy E, Leibovici M, Petit C. Characterization of otoconin-95, the major protein of murine otoconia, provides insights into the formation of these inner ear biominerals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:529–534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kowalski PE, Thalmann I, Ornitz DM, Mager DL, Thalmann R. Otoconin-90, the mammalian otoconial matrix protein, contains two domains of homology to secretory phospholipase A2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15345–15350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao T, Roeser T, Staub W, Baier H. A GFP-based genetic screen reveals mutations that disrupt the architecture of the zebrafish retinotectal projection. Development. 2005;132:2955–2967. doi: 10.1242/dev.01861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Yang H, Yamoah EN, Lundberg YW. Gene targeting reveals the role of Oc90 as the essential organizer of the otoconial organic matrix. Dev Biol. 2007;304:508–524. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]