Abstract

Despite the current emphasis in the US on HIV testing and serostatus disclosure as HIV-prevention strategies, little is known about men who have sex with men's (MSM) perceptions of serostatus disclosure by sexual partners. This study used conversation analysis to examine recordings of HIV-test counseling sessions in order to understand how counselors and clients conceptualize and discuss sex partners' disclosure of HIV status. Of 50 test sessions audio-recorded in four publicly funded sites in Northern California, 47 sessions included a discussion about sexual partners' serostatus disclosure, in the vast majority of these (91.5%), counselors and clients avoided directly asserting their knowledge of partners' serostatus. Throughout the discussions, counselors and clients co-constructed the sense of distrust, uncertainty and unknowability of partners' serostatus. The implications of our findings for evaluating the effectiveness of HIV status disclosure as a prevention strategy are discussed.

Keywords: serostatus disclosure, HIV test counseling, MSM

Introduction

HIV-prevention policy in the US emphasizes routine HIV testing and serostatus disclosure to sexual partners (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2003; Janssen et al., 2001). To date, research on HIV serostatus disclosure practices has primarily used surveys to examine sexual communication of HIV-positive populations with their sex partners (Ciccarone et al., 2003; Marks & Crepaz, 2003; Elford, Bolding, Maguire, & Sherr, 2001). Comparatively little is known about HIV-negative people's perceptions of serostatus disclosure in relation to safer sex practices. Instead of using surveys, this study used audio-recordings of HIV-test counseling sessions to analyze patterns in the interactional practices counselors and clients used to discuss sex partners' serostatus disclosure. These patterns illuminate HIV-negative men's perceptions of serostatus disclosure as an HIV-prevention strategy.

Methods

Participants and procedures

This study is based on data collected in 2003 and 2005 from four HIV test sites in Northern California, US that offered free, drop-in HIV and STD testing primarily for men who have sex with men (MSM). Of the 65 male test clients we approached after they checked in for a test session, but prior to seeing the counselor, 50 allowed us to audio-record their session. We obtained verbal consent to record at the start of the session. Clients and counselors were given the option of turning off the microphone during the session, but this option was used only once. Participants also had to agree to a follow-up interview. The analysis for this paper deals only with the audio-recorded test session data, not the follow-up interview data.

Analysis

We analyzed the recorded sessions using conversation analysis (CA). Conversation analysis is a method of studying naturally-occurring social interaction by investigating systematic patterns in the structural organization of talk; it focuses on recurrent interactional practices that are situated in sequences of social actions and grounds the analysis in the understandings displayed by the participants in turns at talk. Conversation analysis research in healthcare settings, including HIV/AIDS counseling (Peräkylä, 1995; Silverman, 1997), describes professional tasks, goals and activities pursued in the interaction. It illuminates the everyday social, moral and technical dilemmas faced by medical practitioners in their encounters with patients, with a focus on practical strategies used to resolve these dilemmas through interaction (cf. Heritage & Maynard, 2006). This practical focus makes CA particularly useful as a tool to evaluate the effectiveness of specific clinical strategies (Barnes, 2005), develop training activities (Pommerantz, 2003) and design work environments (Luff, Hindmarsh & Heath, 2000).

We transcribed the audio-recorded sessions for analysis according to the CA transcription conventions (see Table 1), using Transana 2.20 MU software (Woods, 2007). We then collected segments containing serostatus discussions and identified recurrent patterns in the ways that clients asserted their knowledge of sex partners' serostatus.

Table 1.

Transcription Conventions

| [ | Separate left square brackets indicate a point of overlap onset. |

| = | Equal signs indicate no gap of silence between utterances. |

| (0.5) | Numbers in parentheses indicate silence, measured in seconds and tenths of seconds. |

| (.) | A period in parentheses indicates a micropause of less than 0.2 seconds. |

| . | A period indicates a falling, or final, intonation. |

| , | A comma indicates continuing intonation. |

| ? | A question mark indicates rising intonation. |

| ¿ | An inverted question mark indicates a rising intonation stronger than a comma but weaker than a question. |

| ∷ | Colons indicate the prolongation or stretching of the sound just preceding them. The more colons, the longer the stretching. |

| - | A hyphen indicates that the preceding sound is cut off or self-interrupted. |

| word | Underlining indicates some form of stress or emphasis, either by increased loudness or higher pitch. The more underlining, the greater the emphasis. |

| .hh | H's with a superscripted period indicate inbreaths. The more, the longer. |

| hh | H's indicate outbreaths, and sometimes laughter. The more, the longer. |

| (word) | When all or part of an utterance is in single parentheses, it indicates uncertainty on the transcriber's part. |

Results

Of 50 HIV-test counseling sessions that were audio-recorded, 47 included a discussion about sexual partners' serostatus disclosure with 19 different counselors. The 47 sessions consisted of 24 pre-test sessions, each lasting 12-40 minutes, and 23 rapid test sessions, each lasting 30-60 minutes. Discussions about serostatus disclosure did not differ by the type of testing offered.

Direct versus indirect assertion

Only 8.5% of the clients directly asserted their partners' serostatus as seropositive or seronegative, for instance: ‘My partner's positive’ or ‘He's negative’. In 91.5% of the sessions, counselors and clients avoided directly asserting partners' serostatus. They described partners' serostatus by framing it within the context of prior test results, perceptions and hearsay, as illustrated in the examples below.

Practices of indirect assertion: partners' HIV-seronegative versus - seropositive status

In the 91.5% of the sessions in which counselors and clients avoided directly asserting sex partners' serostatus, their discussion exhibited a dichotomy between partners' seronegative and seropositive disclosure. The examples below represent recurrent practices of indirect assertions. Each example is from a different counselor.

HIV-seronegative status

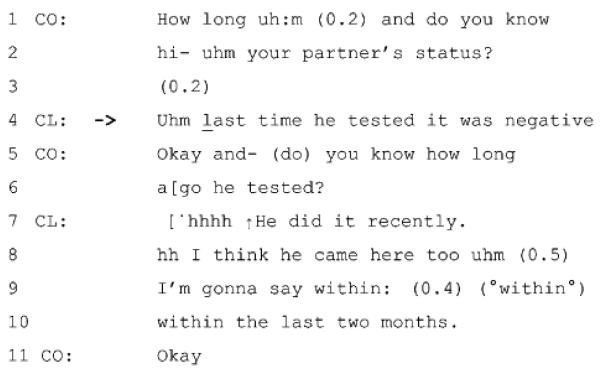

When discussing an HIV-negative disclosure from partners, counselors (CO) and clients (CL) collaborated in stressing their skepticism about partners' status. For instance, in Example 1, in response to the counselor's inquiry about the partner's status (lines 1-2), the client does not claim it as seronegative, e.g. ‘It's negative’. He describes the partner's seronegative status as a result of the last HIV test (line 4). With the use of past tense, ‘last time he tested it was negative’, the client leaves open the possibility that his partner's serostatus could have change recently:

Example 1.

The counselor aligns with the client in not taking the partner's seronegative status at face value, thus orienting to its uncertainty. At line 5-6, he inquires about the timing of the partner's last test, given that antibody window period is normally 3-6 months.

More frequently, clients implied or displayed distrust of HIV-negative disclosure from their sexual partners:

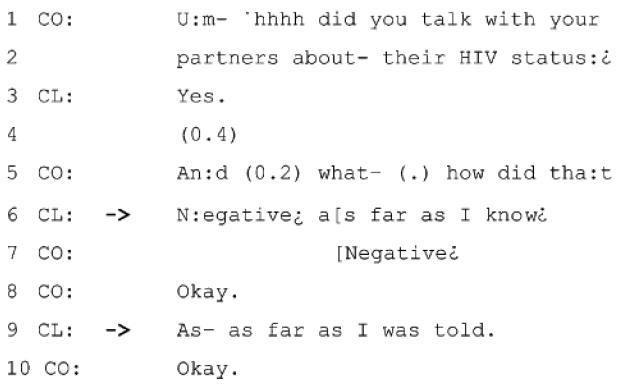

In Example 2, the client responds to the counselor's question (line 5) by articulating his partners' HIV-negative status (line 6). But he immediately qualifies the extent of his knowledge (‘as far as I know’), sanctioning the possibility that the partners' actual serostatus may be different. The client then re-specifies his knowledge as hearsay based on the partners' disclosure (line 9). The client thus avoids claiming any direct knowledge of his partners' serostatus.

Example 2.

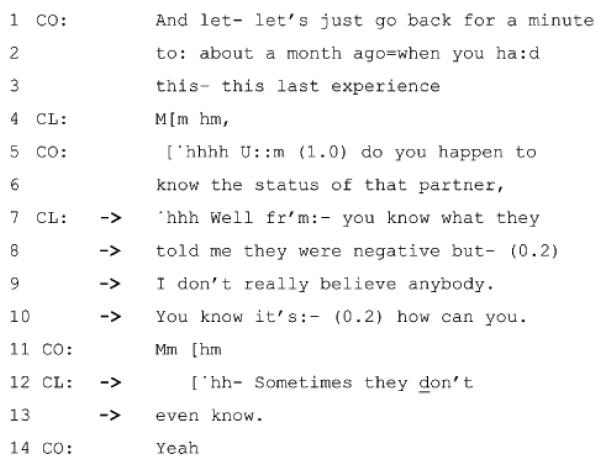

Similarly, in Example 3, the client distances himself from any factual claims about his partners' seronegative disclosure:

Example 3.

In response to the counselor's question (lines 5-6), the client reports the partners' HIV-negative disclosure (lines 7-8), but conveys his skepticism (lines 9-10) and evidences it (line 12-13). By describing the untrustworthiness of HIV-negative disclosure in general, the client not only treats his partners' negative disclosure as subject to distrust, but also displays his understanding of the complex epistemological issues surrounding HIV status disclosure.

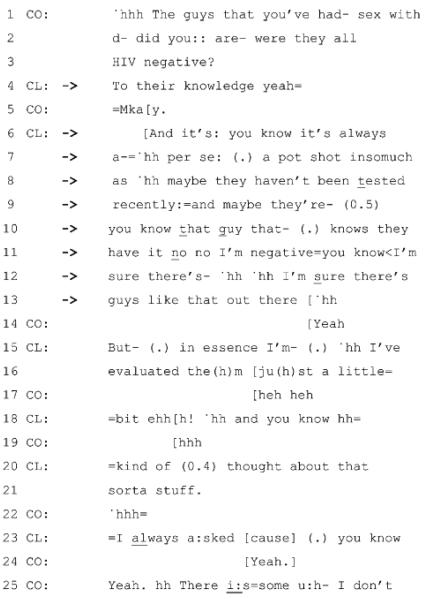

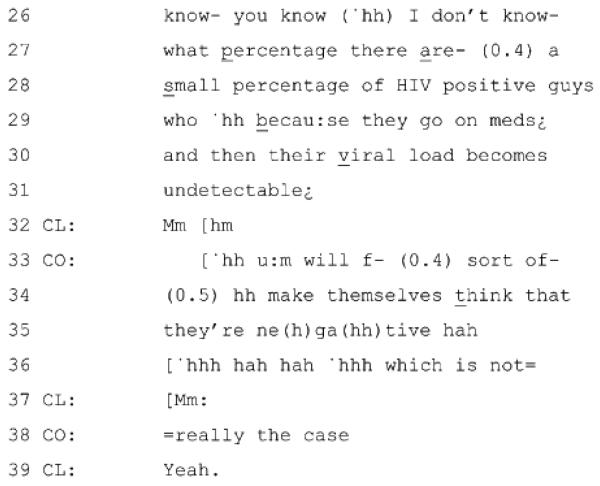

Example 4 illustrates a similar pattern. The client not only displays his skepticism of his partners' seronegative disclosure but also elaborates on its untrustworthiness. At lines 1-3, the counselor produces a question about the partners' HIV-negative status. With the use of past tense, ‘were’, in repair of ‘are-’ (line 2), the counselor limits the inquiry to the time of sexual relationship. The client responds by qualifying his ‘yes’ answer with ‘to their knowledge’ (line 4). He thus withholds affirming the partners' seronegative status. Then the client characterizes HIV-negative disclosure as a ‘pot shot’ (line 7) and downgrades its trustworthiness. He further elaborates on the sources of distrust (lines 8-13), displaying his knowledge about the uncertainty of seronegative status and disclosure practices:

Example 4.

The counselor aligns with the client's distrust and warns him of HIV-positive men who try to pass as HIV-negative because the virus is undetectable (lines 25-38). The counselor and the client later agreed that safer sex should be adopted until they know a person very well (data not shown).

HIV-seropositive status

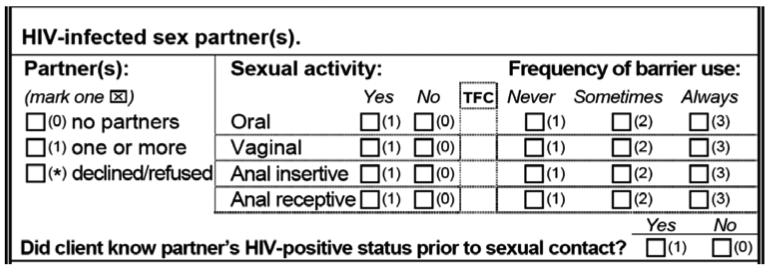

The discussion about partners' seropositive status occurred for the most part in the context of completing a counseling information form required by the State. This form must be completed for each client. The form contains an item on whether the client had (an) HIV-infected sex partner(s), but without any specific guidance for the counselor on how to word the inquiry.

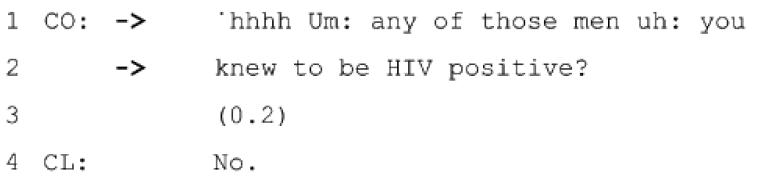

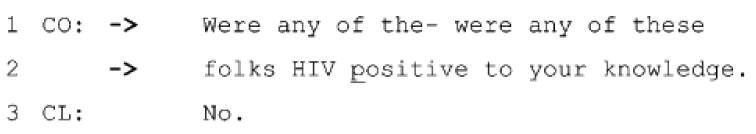

While HIV-seropositive status, unlike seronegative status, is a permanent status, counselors and clients avoided treating it as certain and true. In Examples 5 and 6, the counselor qualifies his inquiry in reference to the client's direct knowledge:

Example 5.

Example 6.

These questions sanction the possibility that there can be partners whose serostatus is unknown or incorrectly known to the client, thus allowing the client to respond without having to make a truth claim.

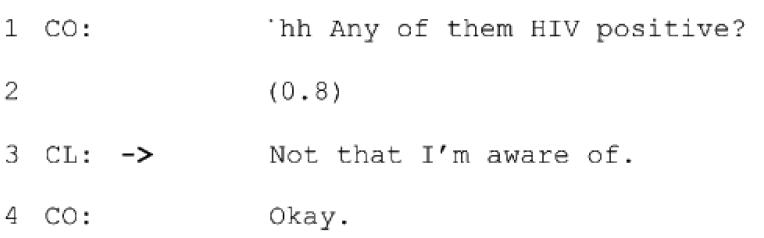

Clients designed their responses in similar ways. They often qualified their claim about the partners' serostatus in terms of their knowledge, as in Example 7:

Example 7.

A ‘no’ answer in response to the question (line 1) would suggest that he knows of serostatus of all the partners. The client rather responds by limiting the claim to what he is aware of (line 3) and displaying caution in claiming direct knowledge of his partner's status.

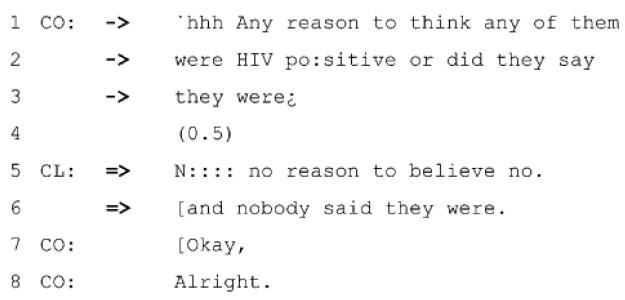

Finally, in Example 8, the counselor and the client designed their talk in ways that avoided any claims about the partners' serostatus:

Example 8.

The counselor first addresses his question to the client's thoughts or inferences (line 1-2) rather than factual knowledge. He immediately formulates another question relating to any direct disclosure by his partners (line 2-3). This question avoids holding the client accountable for knowing the partners' actual serostatus. Rather than producing a ‘no’ in response, the client simply repeats the core of the counselor's questions ( ). He does not provide any information beyond the issues raised by the counselor and thus avoids claiming any knowledge of his partners' serostatus.

The participants' co-alignment

Counselors and clients aligned with one another in their perceptions of partners' serostatus disclosure. They shared a tendency to avoid taking partners' serostatus at face value by framing their discussion in terms of the uncertainties around HIV antibody testing and disclosure practices in the community. The examples above demonstrated that the sense of distrust and unknowability of the partners' serostatus was co-constructed during the session.

Discussion

HIV-test counseling guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that test counseling in publicly funded sites include a discussion about the importance of disclosing serostatus to sex partners (CDC, 2003). Integral to such a discussion is how counselors and clients conceptualize the knowledge gained from sex partners' serostatus disclosures. We identified three major patterns in the ways that counselors and clients discussed sex partners' serostatus disclosure. First, in the majority of the sessions (91.5%), counselors and clients avoided directly asserting partners' serostatus. Second, they treated both positive and negative serostatus disclosure as uncertain and untrustworthy. Third, counselors and clients collaborated with one another in constructing a shared understanding about the uncertainty, unknowability and untrustworthiness of HIV disclosure from partners.

The results of our study have significant implications for HIV prevention and serostatus disclosure as a prevention method. First, given the participants' skepticism about serostatus disclosure from sex partners, our data suggest that serostatus disclosure may not be an effective HIV-prevention strategy, at least among seronegative populations. Our findings may shed light on the conflicting findings about the relationship between serostatus disclosure to sex partners and safer sex practices reported in the literature. Some researchers found no associations between serostatus disclosure and unprotected sex behaviors (Marks & Crepaz, 2001; Ostrow et al., 1989; Wolitski, Rietmeijer, Goldbaum, & Wilson, 1998), whereas others reported a higher prevalence of protected sex with disclosure than with non-disclosure of serostatus (De Rosa & Marks, 1998). Moreover, much research reports that non-disclosure to sex partners is common, ranging from 2-66% (Ciccarone et al., 2003; Hays et al., 1993; Marks & Crepaz, 2001, Marks, Richardson, & Maldonado, 1991; Marks et al., 1994; Perry et al., 1994; Schnell et al., 1992; Wolitski et al., 1998). Many MSM rather make inferences about their partners' serostatus through various physical and behavioral cues and contextual factors (Gold & Skinner, 1996; Gold, Skinner, & Hinchy, 1999; Parsons et al., 2006; Serovich, Oliver, Smith, & Mason, 2005). These findings, in combination with our analysis, suggest that the current emphasis on serostatus disclosure as a prevention strategy should be reconsidered. Men who have sex with men often avoid directly disclosing their status (Elford et al., 2001; Sheon & Crosby, 2004). When they do disclose, the disclosure may be dismissed as unreliable or it may not necessarily lead to safer sex behaviors.

Second, the results of this study suggest that clients may receive incoherent HIV-prevention messages about serostatus disclosure. As mentioned earlier, the CDC recommends routine testing to facilitate serostatus disclosure between sex partners and that test counselors stress the importance of serostatus disclosure to partners. Although the counselors in our data did advise clients to talk with their partners about their status before having sex, serostatus disclosure from partners was generally perceived as an unreliable indicator of actual serostatus. Indeed, quite a few counselors in our dataset advised clients not to rely on partners' disclosure in making safer sex decisions. These paradoxical messages may lead clients to disregard prevention messages more generally.

One discussion from our dataset illustrated the ways that these mixed messages had impacted a particular client's behavior. During the discussion about serostatus disclosure, the client stated, “I would never have sex with somebody who I knew was positive.” The client added that “most people don't know or they would probably lie, so I assume that they're positive. I could say, ‘do you know your HIV status?’ or something like that but I don't do that any more. I just think it's safer just to assume that they're positive and take those precautions and protections.” The client's strategy of universal precautions reflects the dominant safer sex message prior to the widespread deployment of HIV screening. The universal precautions strategy has persisted in uneasy co-existence with later prevention messages based on routine HIV screening and disclosure.

Third, if our data reflect widely shared views on disclosure, it appears that HIV-prevention strategies advocating sero-sorting are primarily relevant for seropositive populations (Janssen et al., 2001). In 1985, HIV antibody screening divided the population into two categories: HIV-positive and HIV-negative. However, these two categories differ fundamentally in their permanence. An HIV-positive person remains so forever - although combination therapies have produced a category of positives with undetectable HIV. A sexually-active, HIV-negative person, on the other hand, could potentially test HIV-positive at any moment given the perennial uncertainties surrounding the antibody window period and routes of transmission. This fundamental difference in permanence between HIV-positive and HIV-negative categories means that it may be more useful to think of HIV status as dichotomized between HIV-positive and HIV-“unknown” because the status of HIV negative, particularly among high risk populations such as MSM, is subject to a high degree of uncertainty (Elford et al., 2001; Sheon & Crosby, 2004). The instability of HIV-negative status may contribute to the perception that HIV serostatus disclosure and sero-sorting is an unreliable prevention strategy for MSM without an HIV-positive diagnosis.

The results of our study should be viewed in light of several caveats. First, this qualitative study is based on a sample of 50 HIV-test counseling sessions with MSM in Northern California. We make no claims about the frequency or distribution of these patterns more generally. Second, the generalizability of the results may be limited by virtue of the specific characteristics of our sample: men willing to record their session and participate in a follow-up interview. Finally, although audio-recording of the sessions provided access to naturally-occurring, mundane interaction, the audio-recording may have introduced its own social desirability bias or observer effect.

Figure 1.

Sexual risk questions on the counseling information form (HIV6). Note: The complete two-page form is available at http://www.palmpal.org/hiv6.pdf

Acknowledgements

The analysis for this paper was supported by the Center for AIDS Prevention Studies at UCSF, grant # P30MH062246-06, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and grant #R01-HD047147-01 funded by the National Institute for Child and Human Development (NICHD). We would like to thank Dan Ciccarone and Edwin Charlebois for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We would especially like to thank the counselors and clients who allowed us to record their HIV-test sessions.

References

- 1.Barnes R. Conversation analysis: A practical resource in the healthcare setting. Medical Education. 2005;39:113–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Incorporating HIV prevention into the medical care of persons living with HIV. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Recommendations and Reports. 2003:1–24. 52(RR-12) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciccarone DH, Kanouse DE, Collins RL, Miu A, Chen JL, Morton SC, et al. Sex without disclosure of positive HIV status in a US probability sample of persons receiving medical care for HIV infection. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(6):949–954. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Rosa CJ, Marks G. Preventive counseling of HIV-positive men and self-disclosure of serostatus to sex partners: New opportunities for prevention. Health Psychology. 1998;17:224–231. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elford J, Bolding G, Maguire M, Sherr L. HIV-positive and -negative homosexual men have adopted different strategies for reducing the risk of HIV transmission. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2001;77(3):224–245. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.3.224-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold RS, Skinner MJ. Judging a book by its cover: Gay men's use of perceptible characteristics to infer antibody status. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 1996;7:39–43. doi: 10.1258/0956462961917032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gold RS, Skinner MJ, Hinchy J. Gay men's stereotypes about who is HIV-infected: A further study. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 1999;10:600–605. doi: 10.1258/0956462991914735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hays RB, McKusick L, Pollack L, Hilliard R, Hoff C, Coates TJ. Disclosing HIV-seropositivity to significant others. AIDS. 1993;7:425–431. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199303000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heritage J, Maynard DW, Heritage J, Maynard DW, editors. Communication in medical care: Interaction between primary care physicians and patients. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2006. Introduction: Analyzing interaction between doctors and patients in primary care encounters; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janssen RS, Holtgrave DR, Valdiserri RO, Shepherd M, Gayle HD, De Cock KM. The serostatus approach to fighting the HIV epidemic: Prevention strategies for infected individuals. Americal Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(7):1019–1024. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luff P, Hindmarsh J, Heath C. Workplace studies: Recovering work practice and informing system design. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marks G, Crepaz N. HIV-positive men's sexual practices in the context of self-disclosure of HIV status. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001;27(1):79–95. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200105010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marks G, Richardson LR, Maldonado N. Self-disclosure of HIV infection to sexual partners. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81:1321–1322. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.10.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marks G, Ruiz MS, Richardson JL, Reed D, Mason HRC, Sotelo M, Turner PA. Anal intercourse and disclosure of HIV infection among seropositive gay and bisexual men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1994;7:866–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostrow DG, Joseph JC, Kessler R, Soucy J, Tal M, Eller M, et al. Disclosure of HIV antibody status: Behavioral and mental health correlates. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1989;1:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsons JT, Severino J, Nanin J, Punzalan JC, von Sternberg K, Missildine W, et al. Positive, negative, unknown: Assumptions of HIV status among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(2):139–149. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.2.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peräkylä A. AIDS counseling: Institutional interaction and clinical practice. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry SW, Card CAL, Moffatt M, Ashman T, Fishman B, Jacobsberg LB. Self-disclosure of HIV infection to sexual partners after repeated counseling. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1994;6:403–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pomerantz A, Glenn P, LeBaron C, Mandelbaum J, editors. Excavating the taking-for granted: Essays in language and social interaction. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. Modelling as a teaching strategy in clinical training: When does it work? [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnell DJ, Higgins DL, Wilson RM, Goldbaum G, Cohn DL, Wolitski RJ. Men's disclosure of HIV test results to male primary sex partners. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;92:1675–1676. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.12.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serovich JM, Oliver DG, Smith SA, Mason TL. Methods of HIV disclosure by men who have sex with men to casual sex partners. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2005;19(12):823–832. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheon N, Crosby MG. Ambivalent tales of HIV disclosure in San Francisco. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;58:2105–2118. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverman D. Discourses of counseling: HIV counseling as social interaction. Sage; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolitski1 RJ, Rietmeijer CAM, Goldbaum GM, Wilson RM. HIV serostatus disclosure among gay and bisexual men in four American cities: General patterns and relation to sexual practices. AIDS Care. 1998;10(5):599–610. doi: 10.1080/09540129848451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woods DK. Transana 2.20 multi-user software for transcription and analysis of audio and video data. 2007 Recovered, from http://www.transana.org. [Google Scholar]