Abstract

Recent developments in the study of host–pathogen interactions have fundamentally altered our understanding of the nature of Staphylococcus aureus infection, and previously held tenets regarding the role of the granulocyte are being cast aside. Novel mechanisms of pathogenesis are becoming evident, revealing the extent to which S. aureus can evade neutrophil responses successfully by resisting microbicides, surviving intracellularly and subverting cell death pathways. Developing a detailed understanding of these complex strategies is especially relevant in light of increasing staphylococcal virulence and antibiotic resistance, and the knowledge that dysfunctional neutrophil responses contribute materially to poor host outcomes. Unravelling the biology of these interactions is a challenging task, but one which may yield new strategies to address this, as yet, defiant organism.

Keywords: apoptosis, inflammation, necrosis, neutrophil, S. aureus

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a formidable and resilient human pathogen, as evidenced by its inexorable rise over recent years. Multiple mechanisms of virulence, together with the evolution of strategies to resist antibiotics, have contributed to its disquieting success. Duly, it is the subject of major political as well as scientific attention. Classically, neutrophils represent the major host defence cells against this organism, yet recent work suggests that staphylococcal actions render granulocytes ineffectual. Restoring their potency may offer the key to reversing failures of innate immunity.

Clinical relevance

Approximately 30% of the population is colonized with S. aureus either chronically or intermittently [1], although this is of no pathological consequence per se. Colonization is, however, linked intimately to disease as it is a major risk factor for invasive infection, and it is partly these carriage rates which help S. aureus to thrive as an opportunist [2,3]. Typically, S. aureus exploits vulnerable populations such as the elderly, immunosuppressed or debilitated. Major risk factors include breaches of the skin barrier, often by trauma, intravenous drug use or medical instrumentation and impaired mucosal immunity, for example, due to cystic fibrosis, artificial ventilation or post-influenza infection. These deficiencies provide bacterial access to local tissue and to the bloodstream, facilitating dissemination of infection. Local infections may be highly destructive in situ, while haematogenous spread results in deep-seated invasive disease including septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, pneumonia and endocarditis. In UK hospital patients the impact is manifest: S. aureus is the major cause of surgical site infections and the second most common cause of hospital-acquired bacteraemia [4] and, in this latter setting, mortality rates approach 30% [5]. Resistance to conventional antibiotics exacerbates virulence, exemplified by the ongoing nosocomial methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) epidemic. The emergence of exceptionally virulent community MRSA strains infecting even the young and immunocompetent underlines further the potency of this robust and versatile pathogen [6,7].

The importance of neutrophils in S. aureus infection

There are two key controversies surrounding the interactions between neutrophils and S. aureus. The first questions neutrophil bactericidal function in relation to S. aureus, postulating bacterial survival or even replication within the phagolysosome of this usually inhospitable cell. The second questions the effects of S. aureus on neutrophil cell death. Because both the timing and mode of neutrophil death is linked intimately to their microbicidal function and to the resolution of inflammation, understanding these events will provide insights into pathogenesis.

How well do neutrophils kill S. aureus?

Neutrophils are highly efficient at killing phagocytosed pathogens. They engage a complex cascade of cellular events to eradicate pathogens via oxidative and non-oxidative mechanisms. Following bacterial phagocytosis, the nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) enzyme complex and nitric oxide (NO) synthase immediately generate reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates (ROI, RNI) within the phagosomal compartment, molecules which are implicated directly in microbicidal activity [8]. Lysosomes laden with proteases, cathepsins, defensins and other anti-microbial proteins fuse rapidly with the phagosome, discharging their potent contents into the phagolysosome. The generation of superoxide by the NADPH complex permits activation of granule proteases within the acidified phagolysosome, thus linking oxidative and non-oxidative bactericidal mechanisms [9]. Neutrophils are also capable of killing non-phagocytosed pathogens through the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), comprising tangles of chromatin and granule proteins which are released by rupture of the neutrophil cell membrane. These structures ensnare bacteria and kill them by exposure to high local concentrations of anti-microbial molecules [10,11].

The consequences of neutrophil deficiencies in number or function substantiate their critical bactericidal role, as affected patients succumb to repeated bacterial infections. Evidence provided by patients with genetic defects implicates neutrophils in opposing S. aureus specifically [12,13]. Patients susceptible to recurrent S. aureus infection include those with chronic neutropenia such as severe congenital neutropenia (SCN), impaired neutrophil migration such as leucocyte adhesion deficiency 1 [13,14] and those with disorders of intracellular killing. This latter group includes patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), who exhibit profoundly impaired oxidative killing due to defective assembly of the NADPH oxidase complex [15,16] and Chediak Higashi patients, in whom degranulation is impaired due to failure of phagolysosome maturation [13]. Furthermore, experimental work using murine models has attributed roles for specific neutrophil microbicidal proteases to particular pathogens; for example, selectively knocking out neutrophil cathepsin G, but not neutrophil elastase, predisposes to S. aureus infection [17]. There are also numerous in vitro studies that support the neutrophil as the key innate effector cell in controlling S. aureus infection [18–21].

Consistent with the notion that neutrophils are a major resource in the conflict against invading S. aureus, the bacterium invests in a panoply of virulence determinants to avoid recognition and phagocytosis by neutrophils (see Table 1). Several secreted and cell-bound proteins act in concert to effectively thwart neutrophil responses at multiple stages including chemotaxis, opsonization, activation and phagocytosis. These sophisticated mechanisms equip the bacterium with major advantages over neutrophils and are reviewed in more detail by Foster and Rooijakkers [22,23]. Additionally, the acquired immune response is considered weak in the face of this pathogen because the presence of anti-staphylococcal antibodies does not confer protection against further infection [24,25].

Table 1.

Staphylococcus aureus mechanisms to evade neutrophil responses.

| Virulence factor | Effect on neutrophil immunity | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CHIPS | Inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis, phagocytosis and oxidative burst | [103–105] |

| SCIN | Inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis, phagocytosis and oxidative burst | [103,106] |

| ClfA | Inhibits neutrophil phagocytosis | [107] |

| Eap | Binds ICAM-1 and inhibits neutrophil recruitment | [108] |

| Staphylokinase | Inhibits alpha-defensins | [109] |

CHIPS, chemotaxis inhibitory protein of staphylococci; SCIN, Staphylococcal complement inhibitor; ClfA, clumping factor A; Eap, extracellular adherence protein; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1.

Despite this, there is a growing body of evidence which suggests that neutrophil defences are of only limited efficacy against staphylococcal insult. Abscess formation is a typical pathology during S. aureus infection which comprises bacteria and recruited neutrophils, many of which are merely corpses, walled off by a fibrin mesh. This is clearly a neutrophil-rich site and yet it is often a focus of persistent infection, allowing speculation that an abscess represents a frustrated immune response: it can contain infection but is unable to resolve it. Also, patients rendered neutropaenic acutely through the administration of chemotherapy are susceptible to a broad range of pathogens and S. aureus, although important, does not predominate [26]. Although the epidemiology and microbiology depend upon numerous factors, including the presence of intravascular devices and the selective pressure of antibiotics, it is intriguing to speculate how such a ubiquitous, colonizing opportunist is kept in check under these circumstances.

More persuasive, and counter-intuitive, is direct evidence of intracellular survival of S. aureus within neutrophils. Although considered classically an extracellular pathogen, S. aureus is known to possess many virulence determinants which protect it from neutrophil microbicides. For example, physical and electrochemical cell wall properties resist the effects of neutrophil defensins and lysozyme, while neutralizing enzymes and carotenoid pigment confer resistance to ROI [22,27,28]. Both in vitro and in vivo work has supported this premise with the caveat that many of these studies relate to the highly virulent community-acquired MRSA strains. Palazzolo-Balance et al. have demonstrated that S. aureus up-regulates a plethora of virulence factors, including haemolysins, leucotoxins, iron scavengers and stress response genes, when exposed to purified neutrophil-derived anti-microbial factors. Moreover, these potent microbicides, including hydrogen peroxide, hypochlorous acid and azurophilic granule proteins, merely exerted bacteriostatic rather than bactericidal effects [29]. Importantly, Gresham et al., established that intracellular bacteria remain viable and virulent. They described the recovery of viable S. aureus from neutrophils isolated from a murine peritonitis model and that infected neutrophils were sufficient to establish infection in a naive mouse [30]. Electron microscopy revealed that S. aureus strains better able to survive within neutrophils were localized within large vacuoles termed ‘spacious phagosomes’ and phagosomal membranes sometimes appeared partially degraded, suggestive of an early stage of bacterial escape into the cytoplasm. Notably, neutrophil depletion resulted in improved outcome of infection in this study and others [31,32], suggesting that an excess of neutrophils may perversely facilitate infection and the persistence of inflammation. Voyich et al. have also demonstrated S. aureus survival within the neutrophil phagolysosome and, crucially, have also shown spontaneous microbial escape via host cell lysis. Community-acquired strains of MRSA appeared to be more resistant to neutrophil killing and caused more cell lysis compared with hospital strains, correlating bacterial survival directly with aberrant neutrophil death [33]. In accordance with this, Kubica et al. describe the intracellular survival of S. aureus within macrophages whereby the bacteria exist ‘silently’ inside phagolysosomes for several days and subsequently escape by inducing spontaneous cell lysis. This process is dependent upon multiple virulence factors, in particular α-haemolysin [34]. By also exploiting macrophages in this way, S. aureus readily out-manoeuvres two invaluable professional phagocytes that, together, form the first line of cellular innate immune defence.

How does S. aureus influence neutrophil cell death pathways?

Neutrophil cell death pathways

Neutrophils are short-lived cells and in the absence of an activation signal undergo constitutive apoptosis. Apoptosis is a favourable mode of death, as it leads to functional down-regulation of superfluous cells while preserving membrane integrity and promoting clearance by macrophages. Apoptosis is a highly complex and tightly regulated series of intracellular events that culminate in neatly packaged cell corpses which are phagocytosed by tissue macrophages. Molecules central to the apoptotic process include members of the Bcl-2 family, which comprises pro- (Bax, Bak, Bim, Bad) and anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, A1, Mcl-1) proteins, which typically regulate mitochondrial membrane stability. The cysteinyl protease family of caspases, which are held in the cell as inactive proforms, are also fundamental in the death programme [35].

By contrast, necrosis is an unfavourable mechanism of cell death, whereby the potent anti-microbial molecules bound previously within the cell spill into the extracellular space and cause local tissue damage. Unlike apoptosis, necrosis is thought typically to be a passive mode of cell death, occurring as a result of injurious processes including infarction, cancer and inflammation [36]. Because necrotic cells lack the ‘eat me’ signals expressed by apoptotic corpses, clearance of necrotic debris is less efficient, resulting in inappropriate persistence of tissue inflammation [37] as well as impaired bacterial clearance. In light of this, many pathogens, including S. aureus, manipulate neutrophil cell death in order to promote their own survival within the host.

Responses of neutrophils to staphylococci and impact on cell survival

As critical innate immune cells, neutrophils express many of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) [38,39] and it is via these receptors, in part, that neutrophils first detect S. aureus. Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 is considered to be the primary PRR for Gram-positive bacteria, as lipoteichoic acids (LTA) signal through this receptor [40]. TLR-2 is important for both limiting S. aureus carriage [41] and infection [42], as TLR-2−/− mice are highly susceptible to S. aureus challenge [43]. This also holds true in human disease for deficiencies in downstream TLR signalling molecules, including myeloid differentiation primary response gene (MyD88) and interleukin (IL)-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK-4) [44,45], although these molecules are also involved in IL-1 signalling. Staphylococcal-produced phenol-soluble modulins have also been shown to signal via TLR-2 [46], supporting further the role of these receptors in initiating host responses to S. aureus. The other major cell wall component of S. aureus is peptidoglycan. Once thought to be a TLR-2 agonist, peptidoglycan (PGN) is now considered to signal dominantly via intracellular PRRs of the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD) family [47] which have been shown recently to play a crucial role in defence against S. aureus in vivo[48].

Both TLRs and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-2 couple into classic proinflammatory pathways, involving mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP) kinase and nuclear factor kappa (NF-κB) activation [49] that delay neutrophil apoptosis. There is some variation in the described magnitude of neutrophil survival to S. aureus-derived molecules, but in particular a pro-survival effect of LTA via TLR-2 ligation has been demonstrated [50,51]. Kobayashi et al. examined changes in neutrophil gene expression following exposure to bacteria including S. aureus, and found that many genes associated with the cell death programme, such as members of the Bcl-2 family and TLR-2 signalling components, were up-regulated [52]. The initial arrest of spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis potentially enhances the functional longevity of the cell, facilitating its response against the pathogen [39]. This host advantage is circumvented quickly by S. aureus and, given that the microorganism may be able to persist inside neutrophils, delayed apoptosis may even favour the microbe.

Conversely, exposure to S. aureus may instigate apoptosis through the mechanism of phagocytosis-induced cell death (PICD) because this itself is a potent stimulus of apoptosis via ligation of Fcγ receptors [53]. PICD may represent a physiological mechanism evolved to link bacterial killing to safe neutrophil disposal, rather than a pathological consequence of infection, as the phenomenon is also seen with heat-killed S. aureus[54] and inert particles [53].

Regulation of neutrophil apoptosis by S. aureus

Although neutrophils detect the presence of staphylococci and may initiate a response resulting in activation and survival, the bacterium itself also exerts powerful effects on neutrophil survival. There are conflicting reports regarding the influence of S. aureus as a pro- or anti-apoptotic stimulus to neutrophils. The outcome can depend upon the experimental conditions; in particular, MOI, duration of challenge, the presence of contaminating cells and bacterial strain. Findings are therefore context-dependent, which emphasizes the complexity of neutrophil lifespan regulation by multiple influences during bacterial infection. Ocana et al. conclude that MOI is crucial: low bacteria to neutrophil ratios led typically to an inhibition of apoptosis and high bacteria to neutrophil ratios induced apoptosis [55]. The delay of apoptosis was consistent with a mechanism involving bacterial recognition by cell surface receptors such as TLRs. This pro-survival effect can also be achieved indirectly by the actions of cytokines [56], and has been linked recently to autocrine/paracrine IL-6 production by neutrophils themselves in response to S. aureus challenge [55]. In keeping with these observations, in murine models of S. aureus infection mice deficient in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β developed larger lesions and fared worse than wild-type counterparts due to impaired neutrophil recruitment [18]. Because IL-1β exerts many anti-apoptotic effects on leucocyte populations, it is conceivable that the lack of cell survival in these deficient mice also contributes to worsening of infection. However, neutrophils respond only poorly or not at all to IL-1β directly, suggesting that the actions of IL-1β may be mediated indirectly by downstream action of tissue cells or other leucocytes [57,58].

Soluble factors secreted by S. aureus also modulate neutrophil apoptosis. Lundqvist-Gustafsson et al. describe the pro-apoptotic effect of a heat-labile, secreted staphylococcal product mediated in part by activation of p38 MAP kinase [59]. In other studies, the pore-forming toxin Panton–Valentine leucocidin (PVL) is a powerful inducer of neutrophil cell death [60]. While PVL is predominantly a necrosis-inducing toxin, at low concentrations it induces neutrophil apoptosis [60].

Finally, because bacterial uptake and killing are linked to the initiation of neutrophil apoptosis, intracellular survival of S. aureus within neutrophils and subsequent escape via lysis implies again that the bacterium has evolved strategies to suppress apoptosis in particular circumstances.

S. aureus exotoxins modulate neutrophil function and induce necrosis

Neutrophil necrosis not only depletes a pool of valuable immune cells but also generates a proinflammatory environment by releasing toxic intracellular contents. Furthermore, the vicious circle of self-perpetuating inflammation, necrotic chaos and abscess formation may enhance bacterial survival both by providing a ‘niche’ where microorganisms are relatively hidden from the immune system and by weakening the bacterial defences on infiltrating neutrophils, for example by cleavage of chemokine receptors [61]. It is well recognized that S. aureus secretes a number of exotoxins, many of which are activatory or leucolytic in vitro, although their clinical relevance remains highly controversial. This group includes the haemolysins (α, β, γ and δ), leucocidins and phenol-soluble modulins.

Haemolysins facilitate the scavenging of iron, although many of them also have leucolytic properties. Alpha-haemolysin is a pore-forming toxin (PFT) and a prominent virulence factor secreted by almost all clinical strains of S. aureus[62–64]. There is good evidence to support its pathological significance in a number of animal models of disease including pneumonia, peritonitis and septic arthritis [65–68]. Cellular susceptibility to α-haemolysin varies widely and human neutrophils demonstrate a remarkable degree of resistance to this lytic agent [69]. None the less, the neutrophil-α-haemolysin interaction is not inert, instead modulating neutrophil adherence to endothelial cells and leukotriene generation [70–72]. This potential sequence of events may result in endothelial dysfunction, which has been implicated in animal models of sepsis [73].

Beta-haemolysin is a magnesium-dependent sphingomyelinase C with more potent haemolytic than leucolytic activity. Variable effects have been reported on nucleated cells, in some studies with human lymphocytes and neutrophils appearing susceptible in vitro[74,75]. More recent work has revealed that β-haemolysin is a potent inhibitor of IL-8 production from endothelial cells and thus impedes neutrophil transmigration [76]. The pathological relevance of this exotoxin in human disease is by no means clear, however, with few experimental mammalian models to date supporting its role [77].

Delta-haemolysin, another PFT, exerts significant proinflammatory effects by activating neutrophils in vitro. It can act both as a priming agent in the presence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α[78], and also as a direct activator of neutrophils, generating ROI and platelet-activating factor, provoking the release of granule enzymes and modulating leukotriene generation [79,80].

Some of the most important leucolytic toxins secreted by S. aureus are the bicomponent leucotoxins, including γ-haemolysin and leucocidins such as PVL. Gamma haemolysin is a prominent haemolysin, secreted by 99% of S. aureus strains. Its leucolytic and activatory actions on neutrophils are also well established [81–83], and a number of studies have validated its role as a relevant virulence determinant in mammalian models of disease [67,84,85]. By contrast, PVL demonstrates a remarkable and exclusive affinity for leucocytes alone, with little haemolytic effect in humans [86]. Pore formation is clearly demonstrable in neutrophil membranes, forming non-specific cation channels which leads to degranulation and the release of proinflammatory mediators prior to cytolysis [82,86–89]. Recent work suggests that at high concentrations leucotoxins may also inhibit neutrophil oxidative burst, potentially undermining their bactericidal capacity [90].

While PVL's potent cytolytic effects on human neutrophils were first characterized in the 1960s [91], it has been implicated more recently as a key virulence factor associated with necrotizing pneumopathies caused by highly virulent community-acquired MRSA. These infections typically affect immunocompetent individuals, and histological findings are dominated by severe tissue necrosis and neutrophil lysis [92]. A number of factors incriminated PVL as a probable aetiological candidate, including the preferential targeting of leucocytes with a high degree of specificity for neutrophils [83]. Furthermore, epidemiological associations exist between community-acquired MRSA, necrotizing pneumonia and PVL [92–95]. Although some mammalian models of pneumonia have supported this view [96] other groups dispute this, citing a limited role for PVL and implicating alternative virulence factors [65,97–99].

Finally, novel and highly effective leucolytic agents are emerging in association with CA-MRSA. Phenol-soluble modulins are cytolytic peptides first described in S. epidermidis infections, which are generating considerable interest as important virulence determinants of CA-MRSA. These pore-forming toxins attract, activate and lyse neutrophils [100,101]. Not only is leucocidal activity demonstrable in vitro, but there is also supportive evidence of in vivo virulence in murine skin abscess and bacteraemia models [101].

Conclusions

Reconciling the effects of so many influences on neutrophil lifespan is problematic. With respect to the regulation of programmed cell death, it is likely that competing pro- and anti-apoptotic stimuli converge in the neutrophil and their summative effect, to some extent, determines outcome. In most circumstances neutrophil apoptosis is a desirable consequence, aiding neutrophil clearance and the resolution of infection, but manipulation of neutrophil death by acceleration, suppression or bypass of apoptosis may commandeer the process to pathogen advantage [52].

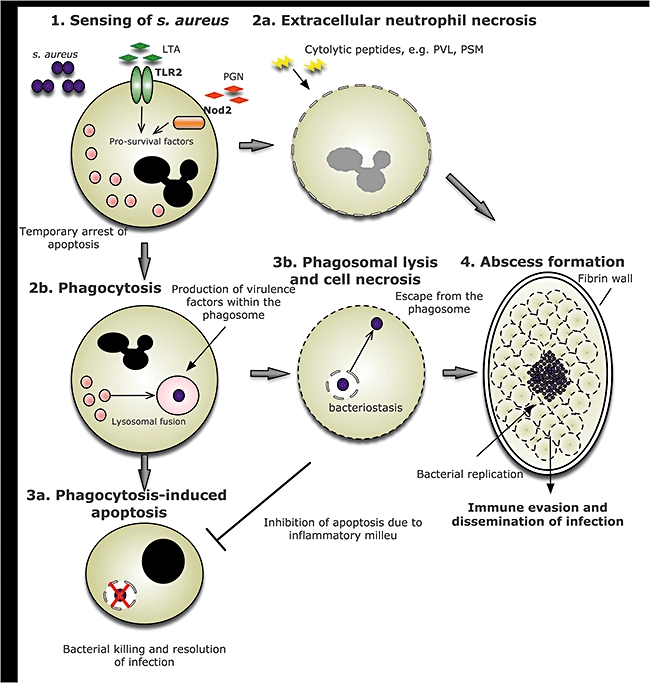

With respect to the induction of neutrophil lysis, the repertoire of secreted leucolytic agents and the clinical manifestations of necrotizing infection reflect how successful S. aureus can be as an extracellular pathogen. However, in light of mounting evidence that S. aureus can survive intracellularly after phagocytic uptake, these toxins may in fact play a key role in facilitating escape from the phagosome [102]. Subsequent neutrophil lysis could enable S. aureus to escape infection foci and allow pathogen dissemination. In either case, cell death proceeds via the unsafe mechanism of cellular necrosis and the adverse consequences of failure of neutrophil apoptosis are evident. A schematic representation of the potential ways that S. aureus may subvert the neutrophil response is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms by which Staphylococcus aureus–neutrophil interactions may lead to abscess formation. Initial sensing of Staphylococcus aureus is carried out mainly by the pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-2. The subsequent signalling leads to the generation of pro-survival molecules which serve to ‘prime’ the neutrophil and thus delay apoptosis temporarily (1). Extracellular bacterial factors, including Panton–Valentine leucocidin (PVL) and phenol-soluble modulins (PSM), have direct effects upon the neutrophil, leading to cell necrosis (2a). Intact neutrophils phagocytose S. aureus, which becomes confined within the phagosome (2b). The desirable outcome is for bacterial killing to take place in the phagosome as a result of activation of anti-microbial proteases and the generation of oxidative stress, following which the cell would undergo apoptosis and be cleared by tissue macrophages (3a). S. aureus may subvert this mechanism by synthesizing virulence factors including lytic proteins within the phagosome, which cause rupture of both the phagosomal and plasma membrane (3b). Bacteria then escape from the cell and potentially utilize the cell contents to fuel replication. Accumulation of cell corpses contributes to abscess formation and inflammation, providing a niche which is relatively hidden from infiltrating immune cells, allowing bacterial replication and ultimately systemic dissemination (4). LTA, lipoteichoic acid; PGN, peptidoglycan.

Overall, we have a limited and inadequate understanding of the complex interactions between S. aureus and the innate immune response. This is especially evident when contrasting its peaceful existence as a colonizer compared with its demonstrable aggression as a pathogen. S. aureus has proved itself to be a sophisticated pathogen. It is remarkably capable of disabling the neutrophil, resisting potent bactericidal mechanisms and inducing aberrant neutrophil death. The emergence of highly pathogenic strains, which are adept at targeting the neutrophil, underlines not only their own virulence but also the key importance of the neutrophil. Gaining insight into the molecular basis of staphylococcal success may enable future therapies targeted at enhancing neutrophilic defences against S. aureus. Restoring neutrophil potency may rest not only on addressing bactericidal mechanisms but also on re-engaging subverted mechanisms of cell death.

Acknowledgments

I. S. is supported by a MRC Senior Clinical Fellowship (G116/170). S. A. is supported by a MRC Clinical Research Fellowship (R-111/251-11-1).

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC, et al. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:751–62. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Belkum A, Melles DC, Nouwen J, et al. Co-evolutionary aspects of human colonisation and infection by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;9:32–47. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health Protection Agency. Surveillance of Healthcare Associated Infections Report. Available at: http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1216193832294 (accessed July 2008)

- 5.Wyllie DH, Crook DW, Peto TE. Mortality after Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in two hospitals in Oxfordshire, 1997–2003: cohort study. BMJ. 2006;333:281. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38834.421713.2F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zetola N, Francis JS, Nuermberger EL, Bishai WR. Community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an emerging threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:275–86. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers HF. Community-associated MRSA – resistance and virulence converge. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1485–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Involvement of superoxide and myeloperoxidase in oxygen-dependent killing of Staphylococcus aureus by neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3512–17. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3512-3517.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segal AW. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, et al. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:231–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spickett GP. Immune deficiency disorders involving neutrophils. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:1001–5. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.051185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakshman R, Finn A. Neutrophil disorders and their management. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:7–19. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abramson JS, Mills EL, Sawyer MK, Regelmann WR, Nelson JD, Quie PG. Recurrent infections and delayed separation of the umbilical cord in an infant with abnormal phagocytic cell locomotion and oxidative response during particle phagocytosis. J Pediatr. 1981;99:887–94. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segal BH, Leto TL, Gallin JI, Malech HL, Holland SM. Genetic, biochemical, and clinical features of chronic granulomatous disease. Medicine (Balt) 2000;79:170–200. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liese J, Kloos S, Jendrossek V, et al. Long-term follow-up and outcome of 39 patients with chronic granulomatous disease. J Pediatr. 2000;137:687–93. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.109112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reeves EP, Lu H, Jacobs HL, et al. Killing activity of neutrophils is mediated through activation of proteases by K+ flux. Nature. 2002;416:291–7. doi: 10.1038/416291a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller LS, Pietras EM, Uricchio LH, et al. Inflammasome-mediated production of IL-1beta is required for neutrophil recruitment against Staphylococcus aureus in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:6933–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caver TE, O'Sullivan FX, Gold LI, Gresham HD. Intracellular demonstration of active TGFbeta1 in B cells and plasma cells of autoimmune mice. IgG-bound TGFbeta1 suppresses neutrophil function and host defense against Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2496–506. doi: 10.1172/JCI119068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kielian T, Barry B, Hickey WF. CXC chemokine receptor-2 ligands are required for neutrophil-mediated host defense in experimental brain abscesses. J Immunol. 2001;166:4634–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molne L, Verdrengh M, Tarkowski A. Role of neutrophil leukocytes in cutaneous infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6162–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6162-6167.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster TJ. Immune evasion by staphylococci. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:948–58. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rooijakkers SH, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA. Staphylococcal innate immune evasion. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wergeland HI, Haaheim LR, Natas OB, Wesenberg F, Oeding P. Antibodies to staphylococcal peptidoglycan and its peptide epitopes, teichoic acid, and lipoteichoic acid in sera from blood donors and patients with staphylococcal infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1286–91. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.6.1286-1291.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gjertsson I, Hultgren OH, Stenson M, Holmdahl R, Tarkowski A. Are B lymphocytes of importance in severe Staphylococcus aureus infections? Infect Immun. 2000;68:2431–4. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2431-2434.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viscoli C, Varnier O, Machetti M. Infections in patients with febrile neutropenia: epidemiology, microbiology, and risk stratification. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(Suppl. 4):S240–5. doi: 10.1086/427329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bera A, Herbert S, Jakob A, Vollmer W, Gotz F. Why are pathogenic staphylococci so lysozyme resistant? The peptidoglycan O-acetyltransferase OatA is the major determinant for lysozyme resistance of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:778–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu GY, Essex A, Buchanan JT, et al. Staphylococcus aureus golden pigment impairs neutrophil killing and promotes virulence through its antioxidant activity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:209–15. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palazzolo-Ballance AM, Reniere ML, Braughton KR, et al. Neutrophil microbicides induce a pathogen survival response in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 2008;180:500–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gresham HD, Lowrance JH, Caver TE, Wilson BS, Cheung AL, Lindberg FP. Survival of Staphylococcus aureus inside neutrophils contributes to infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:3713–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLoughlin RM, Lee JC, Kasper DL, Tzianabos AO. IFN-gamma regulated chemokine production determines the outcome of Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Immunol. 2008;181:1323–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLoughlin RM, Solinga RM, Rich J, et al. CD4+ T cells and CXC chemokines modulate the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus wound infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10408–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508961103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voyich JM, Braughton KR, Sturdevant DE, et al. Insights into mechanisms used by Staphylococcus aureus to avoid destruction by human neutrophils. J Immunol. 2005;175:3907–19. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubica M, Guzik K, Koziel J, et al. A potential new pathway for Staphylococcus aureus dissemination: the silent survival of S. aureus phagocytosed by human monocyte-derived macrophages. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bianchi SM, Dockrell DH, Renshaw SA, Sabroe I, Whyte MK. Granulocyte apoptosis in the pathogenesis and resolution of lung disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;110:293–304. doi: 10.1042/CS20050178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haslett C. Granulocyte apoptosis and inflammatory disease. Br Med Bull. 1997;53:669–83. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirsch T, Marchetti P, Susin SA, et al. The apoptosis–necrosis paradox. Apoptogenic proteases activated after mitochondrial permeability transition determine the mode of cell death. Oncogene. 1997;15:1573–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayashi F, Means TK, Luster AD. Toll-like receptors stimulate human neutrophil function. Blood. 2003;102:2660–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurt-Jones EA, Mandell L, Whitney C, et al. Role of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) in neutrophil activation: GM-CSF enhances TLR2 expression and TLR2-mediated interleukin 8 responses in neutrophils. Blood. 2002;100:1860–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwandner R, Dziarski R, Wesche H, Rothe M, Kirschning CJ. Peptidoglycan- and lipoteichoic acid-induced cell activation is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17406–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gonzalez-Zorn B, Senna JP, Fiette L, et al. Bacterial and host factors implicated in nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in mice. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1847–51. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1847-1851.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoebe K, Georgel P, Rutschmann S, et al. CD36 is a sensor of diacylglycerides. Nature. 2005;433:523–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Akira S. Cutting edge: TLR2-deficient and MyD88-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Immunol. 2000;165:5392–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Bernuth H, Picard C, Jin Z, et al. Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with MyD88 deficiency. Science. 2008;321:691–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1158298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ku CL, von Bernuth H, Picard C, et al. Selective predisposition to bacterial infections in IRAK-4-deficient children: IRAK-4-dependent TLRs are otherwise redundant in protective immunity. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2407–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hajjar AM, O'Mahony DS, Ozinsky A, et al. Cutting edge: functional interactions between toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR1 or TLR6 in response to phenol-soluble modulin. J Immunol. 2001;166:15–19. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Viala J, et al. Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8869–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deshmukh HS, Hamburger JB, Ahn SH, McCafferty DG, Yang SR, Fowler VG., Jr. The critical role of NOD2 in regulating the immune response to Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1376–82. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00940-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:816–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lotz S, Aga E, Wilde I, et al. Highly purified lipoteichoic acid activates neutrophil granulocytes and delays their spontaneous apoptosis via CD14 and TLR2. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:467–77. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0803360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sabroe I, Prince LR, Jones EC, et al. Selective roles for Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 in the regulation of neutrophil activation and life span. J Immunol. 2003;170:5268–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kobayashi SD, Braughton KR, Whitney AR, et al. Bacterial pathogens modulate an apoptosis differentiation program in human neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10948–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1833375100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coxon A, Rieu P, Barkalow FJ, et al. A novel role for the beta 2 integrin CD11b/CD18 in neutrophil apoptosis: a homeostatic mechanism in inflammation. Immunity. 1996;5:653–66. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamoto A, Taniuchi S, Tsuji S, Hasui M, Kobayashi Y. Role of reactive oxygen species in neutrophil apoptosis following ingestion of heat-killed Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;129:479–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01930.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ocana MG, Asensi V, Montes AH, Meana A, Celada A, Valle-Garay E. Autoregulation mechanism of human neutrophil apoptosis during bacterial infection. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:2087–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luo HR, Loison F. Constitutive neutrophil apoptosis: mechanisms and regulation. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:288–95. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prince LR, Allen L, Jones EC, et al. The role of interleukin-1beta in direct and toll-like receptor 4-mediated neutrophil activation and survival. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1819–26. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63437-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morris GE, Whyte MK, Martin GF, Jose PJ, Dower SK, Sabroe I. Agonists of toll-like receptors 2 and 4 activate airway smooth muscle via mononuclear leukocytes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:814–22. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200403-406OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lundqvist-Gustafsson H, Norrman S, Nilsson J, Wilsson A. Involvement of p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase in Staphylococcus aureus-induced neutrophil apoptosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:642–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Genestier AL, Michallet MC, Prevost G, et al. Staphylococcus aureus Panton–Valentine leukocidin directly targets mitochondria and induces Bax-independent apoptosis of human neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3117–27. doi: 10.1172/JCI22684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hartl D, Latzin P, Hordijk P, et al. Cleavage of CXCR1 on neutrophils disables bacterial killing in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Nat Med. 2007;13:1423–30. doi: 10.1038/nm1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhakdi S, Tranum-Jensen J. Alpha-toxin of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:733–51. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.733-751.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Menestrina G, Dalla Serra M, Comai M, et al. Ion channels and bacterial infection: the case of beta-barrel pore-forming protein toxins of Staphylococcus aureus. FEBS Lett. 2003;552:54–60. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00850-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Menestrina G, Serra MD, Prevost G. Mode of action of beta-barrel pore-forming toxins of the staphylococcal alpha-hemolysin family. Toxicon. 2001;39:1661–72. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(01)00153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bubeck Wardenburg J, Schneewind O. Vaccine protection against Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. J Exp Med. 2008;205:287–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McElroy MC, Harty HR, Hosford GE, Boylan GM, Pittet JF, Foster TJ. Alpha-toxin damages the air-blood barrier of the lung in a rat model of Staphylococcus aureus-induced pneumonia. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5541–4. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5541-5544.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nilsson IM, Hartford O, Foster T, Tarkowski A. Alpha-toxin and gamma-toxin jointly promote Staphylococcus aureus virulence in murine septic arthritis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1045–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1045-1049.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patel AH, Nowlan P, Weavers ED, Foster T. Virulence of protein A-deficient and alpha-toxin-deficient mutants of Staphylococcus aureus isolated by allele replacement. Infect Immun. 1987;55:3103–10. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.3103-3110.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Valeva A, Walev I, Pinkernell M, et al. Transmembrane beta-barrel of staphylococcal alpha-toxin forms in sensitive but not in resistant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11607–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suttorp N, Seeger W, Zucker-Reimann J, Roka L, Bhakdi S. Mechanism of leukotriene generation in polymorphonuclear leukocytes by staphylococcal alpha-toxin. Infect Immun. 1987;55:104–10. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.104-110.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Feinmark SJ, Cannon PJ. Endothelial cell leukotriene C4 synthesis results from intercellular transfer of leukotriene A4 synthesized by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:16466–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grimminger F, Thomas M, Obernitz R, Walmrath D, Bhakdi S, Seeger W. Inflammatory lipid mediator generation elicited by viable hemolysin-forming Escherichia coli in lung vasculature. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1115–25. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.4.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grandel U, Reutemann M, Kiss L, et al. Staphylococcal alpha-toxin provokes neutrophil-dependent cardiac dysfunction: role of ICAM-1 and cys-leukotrienes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1157–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00165.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huseby M, Shi K, Brown CK, et al. Structure and biological activities of beta toxin from Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:8719–26. doi: 10.1128/JB.00741-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marshall MJ, Bohach GA, Boehm DF. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus beta-toxin induced leukotoxicity. J Nat Toxins. 2000;9:125–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tajima A, Seki K, Shinji H, Masuda S. Inhibition of interleukin-8 production in human endothelial cells by Staphylococcus aureus supernatant. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:148–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O'Callaghan RJ, Callegan MC, Moreau JM, et al. Specific roles of alpha-toxin and beta-toxin during Staphylococcus aureus corneal infection. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1571–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1571-1578.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schmitz FJ, Veldkamp KE, Van Kessel KP, Verhoef J, Van Strijp JA. Delta-toxin from Staphylococcus aureus as a costimulator of human neutrophil oxidative burst. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1531–7. doi: 10.1086/514152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kasimir S, Schonfeld W, Alouf JE, Konig W. Effect of Staphylococcus aureus delta-toxin on human granulocyte functions and platelet-activating-factor metabolism. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1653–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1653-1659.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Raulf M, Alouf JE, Konig W. Effect of staphylococcal delta-toxin and bee venom peptide melittin on leukotriene induction and metabolism of human polymorphonuclear granulocytes. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2678–82. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2678-2682.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prevost G, Cribier B, Couppie P, et al. Panton–Valentine leucocidin and gamma-hemolysin from Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 49775 are encoded by distinct genetic loci and have different biological activities. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4121–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4121-4129.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Staali L, Monteil H, Colin DA. The staphylococcal pore-forming leukotoxins open Ca2+ channels in the membrane of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J Membr Biol. 1998;162:209–16. doi: 10.1007/s002329900358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Szmigielski S, Sobiczewska E, Prevost G, Monteil H, Colin DA, Jeljaszewicz J. Effect of purified staphylococcal leukocidal toxins on isolated blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes and peritoneal macrophages in vitro. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1998;288:383–94. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(98)80012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Clyne M, Azavedo J DE, Carlson E, Arbuthnott J. Production of gamma-hemolysin and lack of production of alpha-hemolysin by Staphylococcus aureus strains associated with toxic shock syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:535–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.3.535-539.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Supersac G, Piemont Y, Kubina M, Prevost G, Foster TJ. Assessment of the role of gamma-toxin in experimental endophthalmitis using a hlg-deficient mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. Microb Pathog. 1998;24:241–51. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Colin DA, Mazurier I, Sire S, Finck-Barbancon V. Interaction of the two components of leukocidin from Staphylococcus aureus with human polymorphonuclear leukocyte membranes: sequential binding and subsequent activation. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3184–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3184-3188.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Baba Moussa L, Werner S, Colin DA, et al. Discoupling the Ca(2+)-activation from the pore-forming function of the bi-component Panton–Valentine leucocidin in human PMNs. FEBS Lett. 1999;461:280–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01453-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Konig B, Prevost G, Piemont Y, Konig W. Effects of Staphylococcus aureus leukocidins on inflammatory mediator release from human granulocytes. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:607–13. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hensler T, Konig B, Prevost G, Piemont Y, Koller M, Konig W. Leukotriene B4 generation and DNA fragmentation induced by leukocidin from Staphylococcus aureus: protective role of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and G-CSF for human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2529–35. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2529-2535.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Colin DA, Monteil H. Control of the oxidative burst of human neutrophils by staphylococcal leukotoxins. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3724–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3724-3729.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Woodin AM. Purification of the two components of leucocidin from Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem J. 1960;75:158–65. doi: 10.1042/bj0750158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gillet Y, Issartel B, Vanhems P, et al. Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton–Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients. Lancet. 2002;359:753–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07877-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lina G, Piemont Y, Godail-Gamot F, et al. Involvement of Panton–Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1128–32. doi: 10.1086/313461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tristan A, Bes M, Meugnier H, et al. Global distribution of Panton–Valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, 2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:594–600. doi: 10.3201/eid1304.061316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vandenesch F, Naimi T, Enright MC, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton–Valentine leukocidin genes: worldwide emergence. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:978–84. doi: 10.3201/eid0908.030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Labandeira-Rey M, Couzon F, Boisset S, et al. Staphylococcus aureus Panton–Valentine leukocidin causes necrotizing pneumonia. Science. 2007;315:1130–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1137165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bubeck Wardenburg J, Palazzolo-Ballance AM, Otto M, Schneewind O, DeLeo FR. Panton–Valentine leukocidin is not a virulence determinant in murine models of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1166–70. doi: 10.1086/592053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Voyich JM, Otto M, Mathema B, et al. Is Panton–Valentine leukocidin the major virulence determinant in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease? J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1761–70. doi: 10.1086/509506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Diep BA, Palazzolo-Ballance AM, Tattevin P, et al. Contribution of Panton–Valentine leukocidin in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liles WC, Thomsen AR, O'Mahony DS, Klebanoff SJ. Stimulation of human neutrophils and monocytes by staphylococcal phenol-soluble modulin. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang R, Braughton KR, Kretschmer D, et al. Identification of novel cytolytic peptides as key virulence determinants for community-associated MRSA. Nat Med. 2007;13:1510–14. doi: 10.1038/nm1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jarry TM, Memmi G, Cheung AL. The expression of alpha-haemolysin is required for Staphylococcus aureus phagosomal escape after internalization in CFT-1 cells. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1801–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rooijakkers SH, Ruyken M, van Roon J, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA, van Wamel WJ. Early expression of SCIN and CHIPS drives instant immune evasion by Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1282–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.de Haas CJ, Veldkamp KE, Peschel A, et al. Chemotaxis inhibitory protein of Staphylococcus aureus, a bacterial antiinflammatory agent. J Exp Med. 2004;199:687–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Veldkamp KE, Heezius HC, Verhoef J, van Strijp JA, van Kessel KP. Modulation of neutrophil chemokine receptors by Staphylococcus aureus supernate. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5908–13. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5908-5913.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jongerius I, Kohl J, Pandey MK, Ruyken M, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA, Rooijakkers SH. Staphylococcal complement evasion by various convertase-blocking molecules. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2461–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Higgins J, Loughman A, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA, Foster TJ. Clumping factor A of Staphylococcus aureus inhibits phagocytosis by human polymorphonuclear leucocytes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;258:290–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Haggar A, Ehrnfelt C, Holgersson J, Flock JI. The extracellular adherence protein from Staphylococcus aureus inhibits neutrophil binding to endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6164–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.6164-6167.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jin T, Bokarewa M, Foster T, Mitchell J, Higgins J, Tarkowski A. Staphylococcus aureus resists human defensins by production of staphylokinase, a novel bacterial evasion mechanism. J Immunol. 2004;172:1169–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]