Abstract

Objective: ACTH-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (AIMAH) is often associated with subclinical cortisol secretion or atypical Cushing’s syndrome (CS). We characterized a large series of patients of AIMAH and compared them with patients with other adrenocortical tumors.

Design and Patients: We recruited 82 subjects with: 1) AIMAH (n = 16); 2) adrenocortical cortisol-producing adenoma with CS (n = 15); 3) aldosterone-producing adenoma (n = 19); and 4) single adenomas with clinically nonsignificant cortisol secretion (n = 32).

Methods: Urinary free cortisol (UFC) and 17-hydroxycorticosteroid (17OHS) were collected at baseline and during dexamethasone testing; aberrant receptor responses was also sought by clinical testing and confirmed molecularly. Peripheral and/or tumor DNA was sequenced for candidate genes.

Results: AIMAH patients had the highest 17OHS excretion, even when UFCs were within or close to the normal range. Aberrant receptor expression was highly prevalent. Histology showed at least two subtypes of AIMAH. For three patients with AIMAH, there was family history of CS; germline mutations were identified in three other patients in the genes for menin (one), fumarate hydratase (one), and adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC) (one); a PDE11A gene variant was found in another. One patient had a GNAS mutation in adrenal nodules only. There were no mutations in any of the tested genes in the patients of the other groups.

Conclusions: AIMAH is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous disorder that can be associated with various genetic defects and aberrant hormone receptors. It is frequently associated with atypical CS and increased 17OHS; UFCs and other measures of adrenocortical activity can be misleadingly normal.

ACTH-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia is a heterogeneous disorder often associated with genetic defects at the germline or the somatic level.

Endogenous Cushing’s syndrome (CS) is due to primary adrenal disease in approximately 15–20% of cases; in these patients, CS is caused mainly by unilateral adenomas (1). Bilateral adrenal lesions occur only in 10–15% of adrenal CS and include primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD) and ACTH-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (AIMAH), also known as massive macronodular adrenal disease (2,3). PPNAD is most frequently associated with Carney complex and is caused mainly by inactivating germline mutations of PRKAR1A and allelic losses of its locus at the 17q22-24 chromosomal region (4,5).

AIMAH is a rare cause of CS, accounting for less than 1% of adrenal CS. Since the review of AIMAH by Lieberman et al. in 1994 (6), a greater number of cases have been reported (7). Several studies demonstrated that the regulation of cortisol secretion in AIMAH (as well as in some unilateral, single adenomas) is mediated by the aberrant expression and function of membrane-bound G protein-coupled receptors such as those for gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), vasopressin, catecholamines, LH/human chorionic gonadotropin, serotonin, IL-I, and leptin (8,9,10,11,12,13,14).

Establishing the diagnosis of AIMAH with CS is based on, first, the clinical phenotype of CS; this is followed by the demonstration of ACTH-independent hypercortisolism and bilateral adrenal nodular enlargement on radiologic imaging. More often than not, diagnosis of AIMAH is difficult because hypercortisolism usually develops slowly over several years, may be cyclical and is frequently associated with subtle clinical manifestations. Radiologic imaging is helpful, but occasionally adrenal nodularity is indistinguishable from that in normal elderly persons (15). Biochemically, too, there is no specific testing for the diagnosis of AIMAH: whereas most patients with PPNAD respond to dexamethasone with a paradoxical (unexpected) increase in glucocorticoid excretion during Liddle’s test, AIMAH patients respond to dexamethasone as patients with the common adrenal cortisol-producing tumors do, requiring final confirmation of the diagnosis by histological examination (16).

In this investigation, we studied genetically and clinically a large series of patients with AIMAH and compared them with patients with other adrenocortical tumors. The data prove the clinical and genetic heterogeneity of the condition in these patients but also demonstrate the large genetic component of the condition. Finally, our study proposes that urinary 17-hydroxycorticosteroid (17OHS) is the best screening text for hypercortisolism in AIMAH.

Patients and Methods

A total of 102 patients were admitted to the National Institutes of Health Warren Magnuson Clinical Center from 2000 to 2008 for the work-up and treatment of adrenocortical tumors under protocol 00CH160. Eighty-two of 102 patients (28 males and 54 females) met the following criteria: 1) evidence for the existence of an adrenocortical tumor, as indicated by imaging studies or biochemical investigation of hormonal secretion; 2) exclusion of Carney complex or other diseases associated with micronodular forms of adrenocortical hyperplasia. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Institutional Review Board approved this study; informed consents were obtained from all subjects.

The 82 subjects whose data were included here were divided into four groups on the basis of their final histological examination or, for those with nonsecreting tumors, biochemical testing and radiological imaging: 1) AIMAH (n = 16); 2) adrenocortical cortisol-producing adenoma with CS (ACS) (n = 15); 3) aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA) (n = 19); and 4) single adenomas with clinically nonsignificant cortisol secretion (SCA) (n = 32).

The following data were analyzed for all subjects, as we have reported elsewhere for the investigation of CS (17): diurnal variation in plasma ACTH and cortisol levels; cortisol levels before and after the overnight 8-mg dexamethasone test; and plasma ACTH and cortisol levels before and after iv administration of 1 μg/kg ovine CRH (oCRH; corticorelin). Urine was collected for 24 h for free cortisol excretion (UFC) and 17-hydroxycorticosteroid (17OHS), and their data are presented as the mean of two consecutive measurements.

Finally, in all patients with AIMAH, a review of their pathological reports (i.e. macroscopic appearance and weights) and histology was conducted. We recorded size and number of nodules and the presence of hyperplasia or atrophy of nonnodular adrenal cortex, as we have reported elsewhere (18).

Provocative tests for the detection of aberrant receptor expression

Provocative tests for the identification of aberrant receptor expression was employed in the AIMAH and ACS subgroups over a 3-d period, as described previously (19,20). The protocol is based on monitoring plasma levels of steroids at 30- to 60-min intervals for 2–3 h during tests that transiently modulate the levels of ligands for potentially aberrant receptors. Initial tests included a posture test performed in a supine position for baseline, followed by a 2-h ambulatory period (to evaluate potential modulation by vasopressin, catecholamines, angiotensin II, and others); this was followed by a standard mixed meal to evaluate the response to fluctuations of gastrointestinal hormones including GIP. On the second day, the administration of 100 μg GnRH iv (gonadorelin, 1 μg/kg, iv, testing for modulation by FSH, LH, GnRH) was followed by 200 μg TRH iv (modulation by TSH, prolactin, TRH) and GHRH (sermorelin, 1 μg/kg, iv). Responses to 1 mg glucagon iv, 10 IU arginine vasopressin im were tested sequentially on the third day. A change of 50% or greater of plasma cortisol was defined as a positive response; a 25–49% change, as a partial response; and a change of less than 25%, as no response; these cutoffs and their justification have been published elsewhere (19,20).

Dexamethasone testing

A 6-d Liddle’s test was conducted for patients with AIMAH, as described elsewhere (16,17,21). After 2 d of baseline measurement of urinary steroid excretion, dexamethasone, 0.5 mg, was given orally every 6 h for 2 d starting at 0600 h; the dose of dexamethasone was then increased to 2 mg every 6 h for the last 2 d of the test. The 24-h UFC and urinary 17OHS were measured on each day and percentage changes from baseline were calculated. 24-h UFC were corrected for body surface area and 17OHS rates were corrected for creatinine excretion (per day per gram creatinine). In all patients, dexamethasone levels were measured on the last day of the test, and this ensured adequate absorption of the medication; in addition, ACTH levels were suppressed (<5 pmol/liter) in all patients on the same day of the test.

Hormone assays

Plasma cortisol and ACTH levels were measured as described elsewhere (22). UFC excretion was measured by direct RIA (23). The intraassay coefficient of variation was 5%, and the interassay coefficient of variation was 10%; urinary 17OHS excretion was measured by using a modification of the colorimetric method as previously described by Murphy (24). The intraassay and interassay coefficients of variation were 6 and 11%, respectively.

Genetic and other molecular tests

Genomic DNAs were obtained from the blood leukocytes in all subjects and the adrenocortical tissues when they underwent surgery (25,26). Mutation analysis was performed for the menin (MEN1), fumarate hydratase (FH), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), GNAS, and PDE11A (phosphodiesterase 11A) genes (26,27,28).

Aberrant receptor expression that was suggested by clinical testing was confirmed by molecular testing as previously published (19,20). The snap-frozen tissue (50–100 mg) was homogenized with 1 ml TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The extracted RNA was treated with deoxyribonuclease digestion to eliminate contaminating genomic DNA using ribonuclease-free deoxyribonuclease set (QIAGEN, catalog no. 79254; Valencia, CA). The RNA was further cleaned up with RNeasy minikit (QIAGEN, catalog no. 74104). The integrity and concentration of the RNA were determined by agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide and ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE). Two micrograms of RNA was reverse transcriptased to cDNA using the oligo(dT) primers in the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen), according the procedures by the manufacturer. PCRs were performed with Biolase DNA polymerase (Bioline, Randolph, MA) and primers specific to the genes of individual receptors and internal control, β-actin. The primers were designed for the receptors of ACTH, V1, V2, V3, GIP, and LH/human chorionic gonadotropin, either flanking the intron or on the exon/exon boundary to prevent the amplification from the genomic DNA (29,30,31). The amplicon products of the PCR were visualized and autographed in agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide under the AlphaImiger 3400 (Imgen Technologies, Alexandria, VA).

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as the mean ± sd (for demographic data) or mean ± se (for all comparisons and the data presented in the figures). Data were analyzed by using SPSS 14.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The one-way ANOVA with post hoc follow-up (Tukey honestly significant difference) for multiple comparisons was used to test for any differences in demographics; for the percentage and frequency among groups in provocative tests, the χ2 test and follow-up pairwise comparison tests were done with cross-tabulation procedure. The Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to assess differences in Liddle test; Mann-Whitney U test was used for post hoc test among groups. For all statistical comparisons, P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographics

The mean age of AIMAH patients was 46.8 yr (46.8 ± 9.8 yr); this was not significantly different from the mean age of patients in other groups (Table 1). The overall gender distribution (female to male) for this study was 54 to 28, a female predominance (65.9% females) that is similar to what has been reported for adrenal tumors in other studies. The only group of patients in which males (n = 12) outnumbered females (n = 7) was the APA group.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory data for all patients with ACTH-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia and other adrenocortical tumors

| AIMAH (n = 16) | ACS (n = 15) | APA (n = 19) | SCA (n = 32) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (F:M ) | 11:5 | 11:4 | 7:12 | 25:7 | |

| Age (yr) | 46.8 ± 9.8 | 44.3 ± 14.8 | 51.2 ± 10.0 | 49.0 ± 10.7 | 0.32 |

| 8 AM cortisol (nmol/liter) | 535.2 ± 198.6a | 538.0 ± 215.2a | 433.2 ± 82.8 | 389.0 ± 140.7 | 0.03 |

| 12 midnight cortisol (nmol/liter) | 435.9 ± 242.8b,c | 471.8 ± 355.9b,c | 168.3 ± 57.9 | 129.7 ± 69.0 | <0.01 |

| ACTH (pmol/liter) | 1.9 ± 2.5b | 0.7 ± 0.4d | 4.8 ± 3.7 | 3.5 ± 2.3 | <0.01 |

| Cortisol, before DEX (nmol/liter) | 527.0 ± 157.3 | 405.6 ± 126.9 | 485.6 ± 209.7 | 449.7 ± 182.1 | 0.35 |

| Cortisol, after DEX (nmol/liter) | 320.0 ± 298.0a,b | 303.5 ± 223.5a | 93.8 ± 88.3 | 85.5 ± 60.7 | <0.01 |

| UFC (nmol/d · g creatinine) | 611.9 ± 320.7c,d | 625.7 ± 448.5c,d | 183.5 ± 123.6 | 135.2 ± 64.0 | <0.01 |

| 17OHS (mmol/d · g creatinine) | 43.1 ± 20.4c,d | 29.8 ± 13.8b | 15.2 ± 10.8 | 18.2 ± 12.7 | <0.01 |

| Change at d 6 in Liddle’s test (%) | |||||

| UFC | 18.0 ± 48.0b,c | 44.6 ± 109.7b,c | −98.7 ± 0.1 | −90.3 ± 15.6 | <0.01 |

| 17OHS | 14.2 ± 47.1b,c | 10.6 ± 44.9a | −61.2 ± 7.5 | −57.5 ± 18.8 | <0.01 |

Conversion factors to metric units are as follows: cortisol, 0.036 to micrograms per deciliter; ACTH, 5.0 to picograms per milliliter; UFC, 0.362 to micrograms per day per gram creatinine.

P < 0.05 compared with SCA.

P < 0.05 compared with APA.

P < 0.01 compared with SCA.

P < 0.01 compared with APA.

Clinical characteristics and baseline glucocorticoid hormone levels

Patients with AIMAH and ACS did not have any diurnal rhythmicity in their cortisol secretion; those with APA and SCA groups had the expected diurnal variation in their midnight to morning cortisol values. Morning cortisol values were higher for patients with AIMAH and ACS, 535.2 ± 198.6 and 538.0 ± 215.2 nmol/liter, respectively, vs. those in patients with SCA (389.0 ± 140.7 nmol/liter, P < 0.05) (Table 1). Patients with AIMAH and ACS had a trend of higher morning cortisol levels than the APA group, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

UFCs were significantly different in patients with AIMAH and ACS vs. those with APA and SCA (611.9 ± 320.7 and 625.7 ± 448.5 nmol/d 183.5 ± 123.6 and 135.2 ± 64.0 nmol/d, respectively, P < 0.01). Patients in the AIMAH group had the highest urinary 17OHS excretion (43.1 ± 20.4 mmol/d · g crn); 17OHS were 29.8 ± 13.8 mmol/d · g crn in patients with ACS (P = 0.08) and 15.2 ± 10.8 and 18.2 ± 12.7 mmol/d · g crn (P < 0.01) in patients with APA and SCA, respectively (Table 1).

Dexamethasone and oCRH testing, and aberrant receptor expression studies

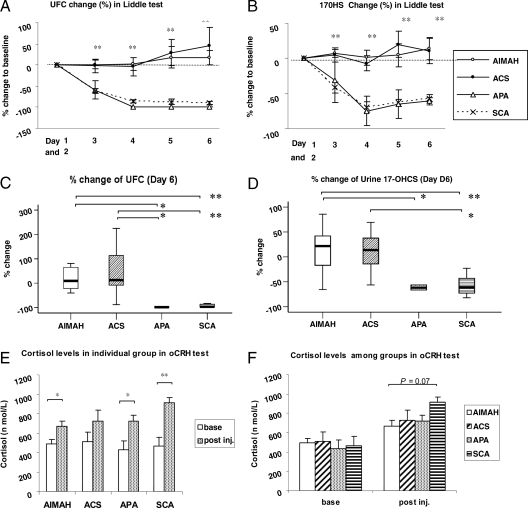

During the Liddle’s test, patients with AIMAH and ACS failed to suppress their glucocorticoid hormone serum levels and urinary excretion rates, consistent with our data in an earlier cohort of similar patients that were studied in our institution (16). In contrast, all patients with APA and SCA suppressed (Fig. 1, A and B). The percentage changes on d 6 from baseline (d 0) were for patients with AIMAH, ACS, APA, and SCA; UFCs 18.0 ± 48.0%, 44.6 ± 109.7%, −98.7 ± 0.1%, and −90.3 ± 15.6% (P < 0.01), respectively; and 17OHS, 14.2 ± 47.1%, 10.6 ± 44.9%, −61.2 ± 7.5%, and −57.5 ± 48.8% (P < 0.01), respectively (Fig. 1, C and D).

Figure 1.

A and B, Serial percentage changes (from d 1 to d 6) compared with the baseline of UFC and 17OHS during Liddle’s test. C and D, Percentage changes compared with baseline in UFCs and 17OHS on d 6 of the Liddle’s test. E and F, Changes in cortisol levels during the oCRH test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Although cortisol levels responded to oCRH testing in all patients, patients with AIMAH, ACS, and APA had lower responses than what was seen in patients with SCA (670.4 ± 55.2, 725.6 ± 110.4, and 722.8 ± 60.7 nmol/liter vs. 915.9 ± 52.4 nmol/liter, respectively P = 0.07) (Fig. 1, E and F). It is noteworthy that in almost none of our patients with CS there was a flat response to oCRH stimulation.

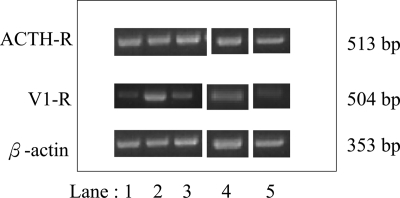

The response rates for the aberrant receptor provocative tests for patients with AIMAH and ACS are shown on Table 2; there were no statistically significant differences in response rates between these two groups of patients with cortisol-producing tumors. In all cases, expression of the aberrant receptor was confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 2) and as previously published (19,20). There was no significant difference in the expression of the aberrant receptors within the AIMAH group.

Table 2.

Response to testing for aberrant receptor expression in patients with AIMAH and ACS

| AIMAH (n = 14) % | ACS (n = 12) % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posture | 4/11 | 36.4 | 3/12 | 25.0 |

| Meal | 1/12 | 8.3 | 0/11 | 0.0 |

| GnRH | 1/6 | 16.7 | 0/8 | 0.0 |

| TRH | 1/3 | 33.3 | 1/8 | 12.5 |

| GHRH | 2/11 | 18.2 | 0/10 | 0.0 |

| Glucagon | 0/10 | 0.0 | 2/11 | 18.2 |

| Vasopressin | 5/11 | 45.5 | 4/10 | 40.0 |

The denominator stands for the number of patients being tested; the numerator stands for the number of patients with positive response (>150% increasing).

Figure 2.

The RT-PCR analysis of ACTH receptor and V1 receptor expression in various adrenal tissue samples compared with the β-actin. Lanes 1 and 2, Type 1 (BMAH) AIMAH patients; lane 3, type 2 (diffuse hyperplasia) AIMAH patient; lane 4, ACS patient; and lane 5, normal control adrenal tissue.

Clinical and molecular genetics

There were three unrelated patients among the 16 with AIMAH who had family history of adrenocortical tumors and/or ACTH-independent CS; the relatives of these patients, however, were not available for investigation. Inheritance of the condition was suggested to be in an autosomal dominant manner based on the constructed pedigrees (data not shown). There were no familial cases in any of the other groups of patients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mutations and other tumors in patients with ACTH-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia and other adrenocortical tumors

| Familial cases | Mutation | Other tumors (number of cases) | Other tumors in family members (number) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIMAH (n = 16) | 3 | MEN1 (Pro494Leu) | Thyroid adenoma (1) | Thyroid cancer (1) in M |

| FH (c.781del7) | Lymphoma (1) | Prostate cancer (1) in F | ||

| APC(c. 4393_4394delAG) | Uterine fibroids (5) | Lung cancer (1) in M | ||

| GNAS(Arg201His), somatic | Parotid tumor (3) | |||

| Parathyroid adenoma (1) | ||||

| ACS (n = 15) | None | None | Parathyroid adenoma (1) | None |

| Nodular goiter (1) | ||||

| APA (n = 19) | None | None | Thyroid nodule (1) | None |

| SCA (n = 32) | None | None | Thyroid nodule (1) | Pancreatic Ca (F, GF on maternal side) |

| Parathyroid adenoma (1) | Uterine Ca (M) | |||

| Cervical Ca (S) | ||||

| Breast Ca (A) | ||||

| Pituitary tumor (F) |

M, Mother; F, father; GF, grandfather; S, sister; A, aunt.

We identified three germline mutations in known genes in three other patients with AIMAH. Interestingly, none of these patients had family history of ACTH-independent CS or any other endocrine condition. One (ADT43.01) presented with AIMAH and hyperparathyroidism, and he was found to have a MEN1 mutation (Pro494Leu) (28); another (ADT06.01) presented with AIMAH and the hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cancer syndrome; she had a heterozygous fumarate hydratase mutation (32); a third patient (ADT52.02) had an APC gene mutation (4393_4394delAG) also in the heterozygote state, and her history included polyps and desmoids tumors. This mutation has been previously reported in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and is predicted to produce a truncated protein (see http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php). There was one additional patient who was found to have a somatic GNAS mutation (Arg201His) in her adrenocortical tumor tissue only; the patient did not have any other signs of McCune-Albright syndrome and was in that sense similar to the patients reported by Fragoso et al. (33). There were no pathogenic mutations in the PRKAR1A gene; one of the three familial AIMAH cases was a carrier of the R867G PDE11A gene polymorphism (27,34). None of the other patients, in any of the groups, was found to carry a mutation in any of the tested genes in the peripheral or tumor DNA.

Tumors in other organs in our AIMAH, ACS, APA, and SCA patients were found in five, two, one, and two cases, respectively. In their families, there were three AIMAH patients with family history of tumors other than in the adrenal gland; the SCA groups had three such patients (Table 3).

Histology of patients with AIMAH

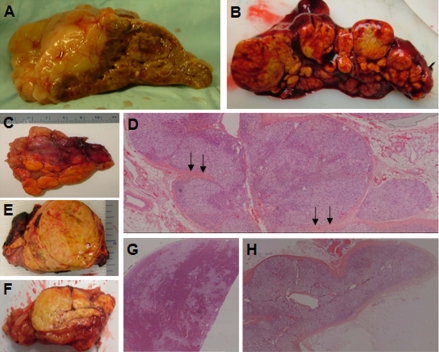

It was recognized that patients with AIMAH could generally be subgrouped in two categories (18) (Fig. 3): those with multiple nodules or discrete adenomas and intervening atrophic cortical tissue [type I AIMAH, bilateral adenomata, or bilateral macronodular adrenocortical hyperplasia (BMAH)] and those with diffuse hyperplasia and no residual normal or surrounding atrophic adrenal cortex (type II AIMAH). Most patients with AIMAH belonged to the second category; the three familial cases and the patients with germline MEN1 and APC and the one with the somatic GNAS mutation belonged to the first group.

Figure 3.

A, Corticotropin-induced hyperplasia. The adrenal is large and nodular, but the overall anatomy and shape of the gland is largely preserved. B and C, Two examples, right and left adrenal gland, respectively, with multiple nodules or discrete adenomas and intervening atrophic cortical tissue (type I AIMAH, BMAH). D, Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (magnification, ×5) of the tissue from C; multiple nodules are clearly visible, and the intervening cortex is atrophic and even sandwiched between adenomas (arrows). E and F, Two examples, right and left adrenal gland, respectively, with diffuse cortical hyperplasia and no residual normal or surrounding atrophic adrenal cortex (type II AIMAH). G, Histology of tissue from E showing a large adenoma in the context of diffuse hyperplasia (H&E staining, ×5). H, Histology of tissue from F showing diffuse cortical hyperplasia (H&E staining, ×5).

Discussion

Although the majority of our patients with AIMAH presented in the fifth decade of life (mean age of 46.8 yr), most had an insidious and atypical form of CS for a number of years. It is characteristic that by the time these patients were operated at the National Institutes of Health and despite their lack of suppression in response to dexamethasone as well as relative loss of their diurnal rhythm in cortisol secretion, almost all of them retained their response to oCRH. As a group, AIMAH patients had higher morning cortisol levels and lower oCRH responses than patients with APAs or SCAs, but their hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis was not completely suppressed. This is a phenomenon that we have described before in patients with PPNAD (17,35), suggesting that oCRH testing is not useful in the investigation of bilateral adrenocortical hyperplasias (BAH) that are generally associated with atypical, milder, chronic, or cyclical forms of CS.

In the absence of the typical paradoxical rise in glucocorticoid hormone excretion rates in response to dexamethasone for micronodular forms of BAH (16,17,18,35), how can one diagnose AIMAH in its early stages? The suggestion of BAH on radiological imaging is the first diagnostic criterion, as we proposed elsewhere (16,36). The present investigation identified another useful diagnostic feature for patients with AIMAH: these patients had high urinary 17OHS excretion, even when their UFC levels were comparable or even lower than those of the ACS group. Urinary 17OHS has long been known to represent the fractions of the corticosteroids possessing a hydroxyl group at position 17 of the steroid structure, including cortisol, cortisone, 6β-hydroxycortisol, tetrahydrocortisol, allotetrahydrocortisol, and tetrahydrocortisone (37,38). Thus, patients with AIMAH appear to excrete in their urine various glucocorticoid metabolites that are not detected by the assays for UFCs; measurement of 17OHS can therefore be a useful and early diagnostic test for patients with suspected atypical or early CS due to AIMAH.

It should be noted that in two patients with ACS, there was a rise in glucocorticoid secretion during Liddle’s test, albeit modest compared with what has been seen in PPNAD and other micronodular forms of BAH (16,35,39). This is consistent with our previous data (16) and may indicate that at least some patients with ACS may be affected by a mild from of micronodular BAH or that PRKAR1A mutations or related genetic defects that were not detected by routine sequencing were present at the tissue level, as we have shown before in at least some cases of AIMAH or ACS (26,40).

Nine AIMAH patients showed aberrant cortisol responses to at least one stimulus; this response rate was consistent with what has been reported in other studies that used a similar testing protocol (10,11,12,14,41,42). In addition, patients with ACS also showed aberrant receptor expression; again, this has also been reported to be a relatively frequent phenomenon (14,41,42,43,44,45). To date, the unexpected regulation of cortisol secretion by receptors for various neuroendocrine substances in ACTH-independent CS remains a biological puzzle; both mouse and human studies indicate that in at least some of these patients, this phenomenon is a primary defect, causative of the CS phenotype (41).

Our clinical and molecular genetic data pointed to significant heterogeneity among our cohort of patients with AIMAH: there were three cases with some (but not extensive) family history of adrenocortical tumors. There are so far seven reports of familial AIMAH, all pointing to an autosomal dominant transmission (31,41,45,46,47). Evidence for heterogeneity included the type of aberrant receptor expression involved in the AIMAH phenotype, the association with various tumors, and various types of germline mutations. First, the aberrant receptors associated with familial AIMAH have most frequently be reported to be the vasopressin (V1 and V2) and the β-adrenergic receptors; the serotonin receptor was present in one family (31,41,45,46,47). In our study, two of the three familial cases had aberrant vasopressin receptors. Second, we found thyroid, parathyroid, and uterine leiomyomatous tumors that have all been previously reported in other patients with AIMAH (31,41,45,46,47); we also found three cases with parotid tumors that have not been previously reported in association with AIMAH.

Finally, an astonishing three of 16 patients (19%) had germline genetic defects in MEN1, FH, and APC, all previously reported pathogenic mutations in the respective genes. A fourth patient had a GNAS somatic (tumor) mutation (R201H) like two of the patients with AIMAH reported by Fragoso et al. (33); none of these patients had any signs of McCune-Albright syndrome. Another patient (with familial AIMAH) carried the R867G PDE11A gene variant (27,34), which, although a relatively frequent gene variant, is located in a highly conserved region of the PDE11A gene and affects enzymatic activity in vitro (34).

Histologically we were able to subclassify our patients with AIMAH in two groups, those with multiple nodules or discrete adenomas and intervening atrophic cortical tissue (type I AIMAH) and those with diffuse hyperplasia (type II AIMAH). Most of our patients belonged to the second category; the three familial cases and the patients with germline MEN1 and APC and somatic GNAS mutations belonged to the first group. However, we found no association of this histopathological observation with distinct expressed receptor pattern or any other clinical feature; it remains unclear whether this observation reflects simply different stages of changes in the adrenal cortex during the development of a chronic disease, or it is in fact a direct effect of the underlying molecular etiology.

We conclude that AIMAH is a heterogeneous disorder that is often associated with genetic defects at both the germline or the somatic level. Determination of urinary 17OHS is a useful diagnostic test for the early detection of abnormal glucocorticoid secretion in this condition; oCRH testing, on the other hand, is not helpful. Histological subgrouping may assist in the future in further investigating the molecular causes of this fascinating condition.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families who participated in our research studies and donated their time for this investigation. We also want to thank Dr. Madson Q. Almeida for expert technical assistance with arts and graphics. We also thank Drs. Stephen Libutti and Anathea Powell from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH), for their collaboration and expert surgical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, intramural NIH project Z01-HD-000642-04 (to Dr. C.A.S.) and in part by the NIH Clinical Center. H.-P.H. was supported for a fellowship at the laboratory of C.A.S. by the Department of Pediatrics, Kaohsiung Municipal Hsiao-Kang Hospital, and College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online June 9, 2009

Abbreviations: ACS, Adrenocortical cortisol-producing adenoma; AIMAH, ACTH-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia; APA, aldosterone-producing adenoma; BAH, bilateral adrenocortical hyperplasias; BMAH, bilateral macronodular adrenocortical hyperplasia; CS, Cushing’s syndrome; GIP, gastric inhibitory polypeptide; oCRH, ovine CRH; 17OHS, 17-hydroxycorticosteroid; SCA, single adenomas with clinically nonsignificant cortisol secretion; UFC, urinary free cortisol.

References

- Nieman LK 2001 Cushing’s syndrome. In: Endocrinology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1691–1720 [Google Scholar]

- Stratakis CA, Kirschner LS 1998 Clinical and genetic analysis of primary bilateral adrenal diseases (micro- and macronodular disease) leading to Cushing syndrome. Horm Metab Res 30:456–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau I, Stratakis CA 2002 Cyclic AMP-dependent signaling aberrations in macronodular adrenal disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 968:240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratakis CA, Kirschner LS, Carney JA 2001 Clinical and molecular features of the Carney complex: diagnostic criteria and recommendations for patient evaluation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:4041–4046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groussin L, Kirschner LS, Vincent-Dejean C, Perlemoine K, Jullian E, Delemer B, Zacharieva S, Pignatelli D, Carney JA, Luton JP, Bertagna X, Stratakis CA, Bertherat J 2002 Molecular analysis of the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) regulatory subunit 1A (PRKAR1A) gene in patients with Carney complex and primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD) reveals novel mutations and clues for pathophysiology: augmented PKA signaling is associated with adrenal tumorigenesis in PPNAD. Am J Hum Genet 71:1433–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman SA, Eccleshall TR, Feldman D 1994 ACTH-independent massive bilateral adrenal disease (AIMBAD): a subtype of Cushing’s syndrome with major diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Eur J Endocrinol 131:67–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos S, Bourdeau I, Lacroix A 2005 Clinical and subclinical ACTH-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia and aberrant hormone receptors. Horm Res 64:119–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiba N, Suda T, Aiba M, Naruse M, Nomura K, Imamura M, Demura H 1995 Lysine vasopressin stimulation of cortisol secretion in patients with adrenocorticotropin-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80:2336–2341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix A, Bolte E, Tremblay J, Dupre J, Poitras P, Fournier H, Garon J, Garrel D, Bayard F, Taillefer R 1992 Gastric inhibitory polypeptide-dependent cortisol hypersecretion—a new cause of Cushing’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 327:974–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix A, Hamet P, Boutin JM 1999 Leuprolide acetate therapy in luteinizing hormone-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 341:1577–1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix A, Tremblay J, Rousseau G, Bouvier M, Hamet P 1997 Propranolol therapy for ectopic β-adrenergic receptors in adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 337:1429–1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pralong FP, Gomez F, Guillou L, Mosimann F, Franscella S, Gaillard RC 1999 Food-dependent Cushing’s syndrome: possible involvement of leptin in cortisol hypersecretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:3817–3822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznik Y, Allali-Zerah V, Chayvialle JA, Leroyer R, Leymarie P, Travert G, Lebrethon MC, Budi I, Balliere AM, Mahoudeau J 1992 Food-dependent Cushing’s syndrome mediated by aberrant adrenal sensitivity to gastric inhibitory polypeptide. N Engl J Med 327:981–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenberg HS, Stratakis CA, Marx C, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Chrousos GP, Bornstein SR 1998 Aberrant interleukin-1 receptors in a cortisol-secreting adrenal adenoma causing Cushing’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 339:27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doppman JL 1997 Problems in endocrinologic imaging. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 26:973–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratakis CA, Sarlis N, Kirschner LS, Carney JA, Doppman JL, Nieman LK, Chrousos GP, Papanicolaou DA 1999 Paradoxical response to dexamethasone in the diagnosis of primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease. Ann Intern Med 131:585–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista DL, Riar J, Keil M, Stratakis CA 2007 Diagnostic tests for children who are referred for the investigation of Cushing syndrome. Pediatrics 120:e575–e586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratakis CA 2009 New genes and/or molecular pathways associated with adrenal hyperplasias and related adrenocortical tumors. Mol Cell Endocrinol 300:152–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau I, D'Amour P, Hamet P, Boutin JM, Lacroix A 2001 Aberrant membrane hormone receptors in incidentally discovered bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia with subclinical Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:5534–5540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix A, Mircescu H, Jamet P 1999 Clinical evaluation of the presence of abnormal hormone receptors in adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. Endocrinologist 9:9–15 [Google Scholar]

- Liddle GW 1960 Tests of pituitary-adrenal suppressibility in the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 20:1539–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanicolaou DA, Yanovski JA, Cutler Jr GB, Chrousos GP, Nieman LK 1998 A single midnight serum cortisol measurement distinguishes Cushing’s syndrome from pseudo-Cushing states. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:1163–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez MT, Malozowski S, Winterer J, Vamvakopoulos NC, Chrousos GP 1991 Urinary free cortisol values in normal children and adolescents. J Pediatr 118:256–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BE 1968 Clinical evaluation of urinary cortisol determinations by competitive protein-binding radioassay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 28:343–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther DF, Bourdeau I, Matyakhina L, Cassarino D, Kleiner DE, Griffin K, Courkoutsakis N, Abu-Asab M, Tsokos M, Keil M, Carney JA, Stratakis CA 2004 Cyclical Cushing syndrome presenting in infancy: an early form of primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease, or a new entity? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:3173–3182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertherat J, Groussin L, Sandrini F, Matyakhina L, Bei T, Stergiopoulos S, Papageorgiou T, Bourdeau I, Kirschner LS, Vincent-Dejean C, Perlemoine K, Gicquel C, Bertagna X, Stratakis CA 2003 Molecular and functional analysis of PRKAR1A and its locus (17q22-24) in sporadic adrenocortical tumors: 17q losses, somatic mutations, and protein kinase A expression and activity. Cancer Res 63:5308–5319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath A, Boikos S, Giatzakis C, Robinson-White A, Groussin L, Griffin KJ, Stein E, Levine E, Delimpasi G, Hsiao HP, Keil M, Heyerdahl S, Matyakhina L, Libe R, Fratticci A, Kirschner LS, Cramer K, Gaillard RC, Bertagna X, Carney JA, Bertherat J, Bossis I, Stratakis CA 2006 A genome-wide scan identifies mutations in the gene encoding phosphodiesterase 11A4 (PDE11A) in individuals with adrenocortical hyperplasia. Nat Genet 38:794–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos MC, Thakker RV 2008 Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1): analysis of 1336 mutations reported in the first decade following identification of the gene. Hum Mutat 29:22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamura N, Taguchi T, Murata Y, Taketa K, Iwashita S, Matsumoto K, Nishikawa T, Toyonaga T, Sakakida M, Araki E 2002 Inherited adrenocorticotropin-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia with abnormal cortisol secretion by vasopressin and catecholamines: detection of the aberrant hormone receptors on adrenal gland. Endocrine 19:319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perraudin V, Delarue C, Lefebvre H, Do Rego JL, Vaudry H, Kuhn JM 2006 Evidence for a role of vasopressin in the control of aldosterone secretion in primary aldosteronism: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:1566–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzosi D, Cartier D, Regnier C, Otal P, Bennet A, Parmentier F, Plantavid M, Lacroix A, Lefebvre H, Caron P 2007 Familial adrenocorticotropin-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia with aberrant serotonin and vasopressin adrenal receptors. Eur J Endocrinol 156:21–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyakhina L, Freedman RJ, Bourdeau I, Wei MH, Stergiopoulos SG, Chidakel A, Walther M, Abu-Asab M, Tsokos M, Keil M, Toro J, Linehan WM, Stratakis CA 2005 Hereditary leiomyomatosis associated with bilateral, massive, macronodular adrenocortical disease and atypical cushing syndrome: a clinical and molecular genetic investigation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:3773–3779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragoso MC, Domenice S, Latronico AC, Martin RM, Pereira MA, Zerbini MC, Lucon AM, Mendonca BB 2003 Cushing’s syndrome secondary to adrenocorticotropin-independent macronodular adrenocortical hyperplasia due to activating mutations of GNAS1 gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:2147–2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath A, Giatzakis C, Robinson-White A, Boikos S, Levine E, Griffin K, Stein E, Kamvissi V, Soni P, Bossis I, de Herder W, Carney JA, Bertherat J, Gregersen PK, Remmers EF, Stratakis CA 2006 Adrenal hyperplasia and adenomas are associated with inhibition of phosphodiesterase 11A in carriers of PDE11A sequence variants that are frequent in the population. Cancer Res 66:11571–11575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell AC, Stratakis CA, Patronas NJ, Steinberg SM, Batista D, Alexander HR, Pingpank JF, Keil M, Bartlett DL, Libutti SK 2008 Operative management of Cushing syndrome secondary to micronodular adrenal hyperplasia. Surgery 143:750–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doppman JL, Chrousos GP, Papanicolaou DA, Stratakis CA, Alexander HR, Nieman LK 2000 Adrenocorticotropin-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia: an uncommon cause of primary adrenal hypercortisolism. Radiology 216:797–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshiro M, Ohno Y, Masaki H, Iwase H, Aoki N 2006 Comprehensive study of urinary cortisol metabolites in hyperthyroid and hypothyroid patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 64:37–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs MH, Christie GA, eds 1972 Advances in steroid biochemistry and pharmacology. In. London and New York: Academic Press; 75–77 [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau I, Lacroix A, Schurch W, Caron P, Antakly T, Stratakis CA 2003 Primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease: paradoxical responses of cortisol secretion to dexamethasone occur in vitro and are associated with increased expression of the glucocorticoid receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:3931–3937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau I, Matyakhina L, Stergiopoulos SG, Sandrini F, Boikos S, Stratakis CA 2006 17q22–24 chromosomal losses and alterations of protein kinase a subunit expression and activity in adrenocorticotropin-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:3626–3632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix A, Baldacchino V, Bourdeau I, Hamet P, Tremblay J 2004 Cushing’s syndrome variants secondary to aberrant hormone receptors. Trends Endocrinol Metab 15:375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mircescu H, Jilwan J, N′Diaye N, Bourdeau I, Tremblay J, Hamet P, Lacroix A 2000 Are ectopic or abnormal membrane hormone receptors frequently present in adrenal Cushing’s syndrome? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:3531–3536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaldi G, Gasc JM, de Keyzer Y, Raffin-Sanson ML, Perraudin V, Kuhn JM, Raux-Demay MC, Luton JP, Clauser E, Bertagna X 1998 Variable expression of the V1 vasopressin receptor modulates the phenotypic response of steroid-secreting adrenocortical tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:2029–2035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertherat J, Contesse V, Louiset E, Barrande G, Duparc C, Groussin L, Emy P, Bertagna X, Kuhn JM, Vaudry H, Lefebvre H 2005 In vivo and in vitro screening for illegitimate receptors in adrenocorticotropin-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia causing Cushing’s syndrome: identification of two cases of gonadotropin/gastric inhibitory polypeptide-dependent hypercortisolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:1302–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuno I, Uchida D, Tanaka T, Koide H, Shigeta A, Ichikawa T, Sasano H, Saito Y 2004 Vasopressin responsiveness of subclinical Cushing’s syndrome due to ACTH-independent macronodular adrenocortical hyperplasia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 60:192–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Hwang R, Lee J, Rhee Y, Kim DJ, Chung UI, Lim SK 2005 Ectopic expression of vasopressin V1b and V2 receptors in the adrenal glands of familial ACTH-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 63:625–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau I 2004 Clinical and molecular genetic studies of bilateral adrenal hyperplasias. Endocr Res 30:575–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]