Abstract

We evaluated the effect of infiltration of dilute solutions of capsaicin, administered before plantar incision, on three pain related behaviors: guarding pain, heat withdrawal latency and mechanical withdrawal threshold. Perineural application of capsaicin was also studied and the appearance of the wound was also evaluated. Dilute solutions of capsaicin 0.025% and 0.10% were infiltrated in the plantar region one day before incision. In another group of rats, perineural capsaicin (1%) was applied to the nerves innervating the plantar aspect of the rat hindpaw. Rats were then tested for pain related behaviors before and after plantar incision and then daily thereafter. Wound appearance was graded and histopathology was evaluated. Infiltration with capsaicin reduced guarding pain and heat hyperalgesia after plantar incision; there were minimal effects on mechanical responses. Perineural capsaicin application produced a similar result. Both capsaicin infiltration and perineural capsaicin application impaired wound apposition. Histologic evaluation also confirmed impaired wound apposition after capsaicin infiltration. In conclusion, dilute solutions of capsaicin have differential effects on pain related behaviors after plantar incision. Based on the antinociception produced by capsaicin both via infiltration and perineural injection, the effect on wound appearance was likely related to its inhibitory effects on pain behaviors and was not necessarily a local effect of the drug.

Perspective

This study demonstrated that capsaicin infiltration before plantar incision produced an analgesic effect that depended upon the stimulus modality tested. When evaluating novel treatments for postoperative pain, studies using a single stimulus modality may overlook an analgesic effect by not examining a variety of stimuli.

Brief Summary Statement

Capsaicin infiltration and perineural capsaicin application decrease guarding pain and heat hyperalgesia after plantar incision.

Introduction

Although many new discoveries are being made in a wide variety of animal pain models, the ability to translate these directly to perioperative pain management has been limited. Thus far, drugs with limited central nervous system side effects that markedly reduce postoperative pain have not been discovered. Recent trials have focused on regional analgesia, anti-inflammatory drugs and gabapentinoids with modest success.

In the future, it is our goal that patients undergo nearly painless surgery. Perhaps the best opportunity to greatly reduce postoperative pain is to further define its peripheral mechanisms for ongoing pain and hyperalgesia, characteristics of patient’s pain complaints after surgery.6 Peripheral targets with reduced central nervous system side effects like dizziness, sedation and respiratory depression could greatly advance perioperative care.4

A significant effort has been made to examine peripheral sensitization caused by incision. From in vivo studies, spontaneous activity in nociceptors is evident in rats that underwent plantar incision; 39% of these nociceptors had spontaneous activity whereas none had spontaneous activity in the sham group.16 In the incised in vitro glabrous skin nerve preparation, heat sensitization was evident and spontaneous activity in nociceptors was associated with a reduced heat threshold in C-fibers suggesting a common mechanism for ongoing activity and heat sensitization.2 We have proposed that ongoing activity mediates non evoked guarding pain suggesting commonalities between guarding pain and heat hyperalgesia.

In the present study, we hypothesized that infiltration of dilute solutions of capsaicin, administered before incision would have different effects on three pain related behaviors: guarding pain, heat withdrawal latency and mechanical withdrawal threshold after plantar incision. Perineural application of capsaicin was also studied and the appearance of the wounds was evaluated. The results of these studies suggest common mechanisms for nonevoked, guarding pain behavior and heat hyperalgesia as a consequence of incisional injury. Distinct mechanisms for mechanical hyperalgesia are suggested.

Methods

General

Experiments, approved by the animal care and use committee, were performed on male Sprague-Dawley rats (weight 275-350 g) (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) that were treated in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Investigations of Experimental Pain in Conscious Animals.29 Rats were housed in pairs before surgery and after the plantar incision, rats were housed individually with bedding consisting of organic cellulose fiber (TREK; Shepherd Specialty Kalamazoo, MI). At the end of the protocol, all animals were euthanized with an overdose of a mixture of pentobarbital (200-400 mg) and phenytoin (25-50 mg) administered intraperitoneally.

Plantar incision

Rats were anesthetized with 2% halothane delivered into a sealed box and then via a nose cone. As described previously,7 a 1 cm longitudinal incision was made through skin and fascia of the plantar aspect of the right hindpaw. Unless otherwise stated, the flexor muscle was not incised. Previous studies showed persistent, pain behaviors with skin and fascia incision.7 After hemostasis with gentle pressure, the skin was apposed with 2 mattress sutures of 5-0 nylon on an FS-2 needle. The wound site was covered with a mixture of polymixin B, neomycin, and bacitracin ointment. After surgery, rats were allowed to recover in their cages before pain behavior tests. The sutures were removed under brief halothane anesthesia after testing on the second postoperative day.

Pain behaviors

On the day of an experiment, rats were placed individually in the testing area covered with a clear plastic cage top (21 × 27 × 15 cm) and allowed to acclimate. Pain behaviors were measured as follows.

Mechanical withdrawal threshold

Withdrawal responses to punctate mechanical stimulation were determined using calibrated Semmes Weinstein monofilaments (North Coast Medical Inc., Morgan Hill, CA) applied from underneath the cage through openings (12 × 12 mm) in the plastic mesh floor to an area adjacent to the wound as described previously.26 Each filament was applied in ascending order once starting with 15 mN until a withdrawal response was elicited. The cut off value, 539 mN, was recorded even if there was no withdrawal response to this force. Three withdrawal tests were performed, the lowest force from the 3 tests (separated by 5 to 10 min) producing a response was considered the withdrawal threshold.26

Heat withdrawal latency

Rats were placed individually on a glass floor covered with clear plastic cage and allowed to acclimate. Withdrawal latencies to radiant heat were assessed by applying a focused radiant heat source underneath a glass floor on the middle of incision. The latency time to evoke a withdrawal was determined with a cut-off value of 20 sec. The intensity of the heat was adjusted to produce withdrawal latency in normal rats of 10 to 15 sec. Each rat was tested at least three times, at an interval of 10 min. The average of at least three trials was used to obtain paw withdrawal latency.26

Guarding pain score

To avoid influencing the position of the paw, guarding pain was measured in separate groups of rats than those used to test heat and mechanical responses. A cumulative pain score was determined to assess guarding pain behaviors as described previously.27 Unrestrained rats were placed on a small plastic mesh floor (grid 8 × 8 mm). Using an angled magnifying mirror, the incised and non-incised paws were viewed. Both paws of each animal were closely observed during one min period repeated for every 5 min for 1 hr. Depending on the position in which each paw was found during the majority of 1 min scoring period a 0, 1 or 2 was given. A score of 0 was given for full weight bearing if the area of the wound was blanched or distorted by the mesh, 1 if the wound area was just touching the mesh without blanching or distortion and 2 if the wound area was completely off of the mesh. The sum of the 12 scores (0-24) obtained during a 1 hr session for each paw was obtained.27

The person performing the behavioral experiments was blind to the treatment, capsaicin versus vehicle.

Experimental protocols

Capsaicin infiltration

After anesthesia with halothane, the intended incision site was infiltrated subcutaneously with 50 μg (dissolved in vehicle A: 1.5% ethanol, 1.5% Tween 80, 97% saline) or 200 μg of capsaicin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; dissolved in vehicle B: 5% ethanol, 5% Tween 80, Fisher Scientific, Chicago,IL, 90 % saline) in a total volume of 200 μl; the two solutions were 0.025% and 0.10% capsaicin, respectively (Fig. 1). The 0.10% capsaicin solution was only partially soluble in vehicle A. Vehicle B was used to dissolve the 0.10% capsaicin solution. Two vehicles were used to so that the amount of tween and alcohol injected into the paw could be minimized in the vehicle A and 0.025% groups. The animals remained anesthetized for the next 30 min to avoid the initial pain produced by capsaicin. Other rats were similarly anesthetized, but received the appropriate vehicle infiltrated into the intended incision site. Each group contained 7-9 rats (see figure legends).

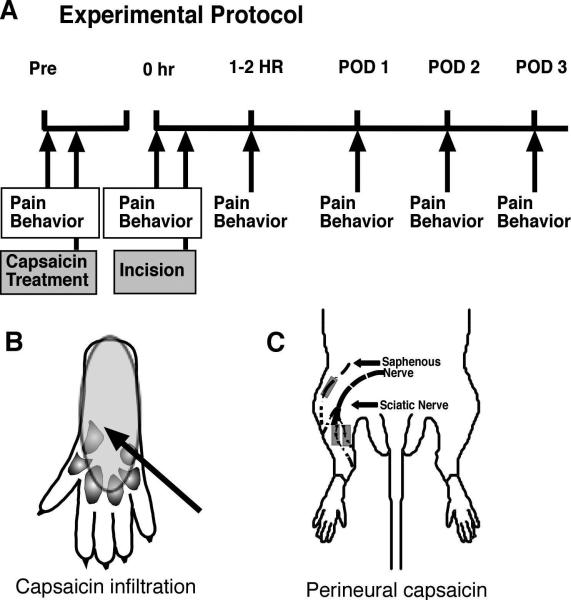

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol (A). For capsaicin infiltration (see schematic part B), rats underwent pain behavioral testing, then subcutaneous drug or vehicle infiltration. The next day, approximately 18 hrs later, pain behaviors were measured and then incision was made. One to two hrs after incision, pain behaviors were measured again and then daily for the next 3 days. For perineural application (see schematic part C), rats underwent pain behavioral testing, then perineural drug or vehicle application. Four days later, pain behaviors were measured and then incision was performed. Two hrs after incision, pain behaviors were measured again and then daily for the next 3 days.

The day after capsaicin injection (or vehicle), rats underwent behavioral testing using the protocols described above (Fig. 1). Withdrawal threshold to punctate stimuli and withdrawal latency to radiant heat were tested. Guarding pain was measured in a separate group. After these tests, rats underwent incision of the plantar aspect of the right hindpaw. After a recovery time of 1 to 2 hrs, pain behaviors were measured again and then daily for the next 3 days. After the last test on postoperative day 3, the wound appearance was evaluated numerically in each rat (0=no incision, 1=well healed, 2=poorly healed, 3=dehisced/separated).

Perineural capsaicin

Rats were anesthetized with 1.5-2% halothane and the popliteal fossa and anterior thigh were prepared in a sterile manner. The skin was incised and the sural and tibial nerves were isolated in the popliteal fossa using blunt dissection. The saphenous nerve was isolated in the thigh. The surrounding tissue was protected from the capsaicin using parafilm. A 1 cm length of nerve was exposed for 30 min to cotton pledgets saturated in 1% capsaicin dissolved in olive oil (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as described.15 To maintain drug exposure to the nerve, additional capsaicin was applied to the pledget at 15 min. After the capsaicin exposure, the nerves were rinsed in saline and the skin was closed with 5-0 nylon suture. The control group underwent nerve exposure and treatment with the vehicle. Rats were allowed 4 days to recover from the intervention before undergoing plantar incision and testing.

Four days after perineural application of capsaicin or vehicle, rats were tested using the pain behavior protocols described above (Fig. 1). Withdrawal threshold to punctate stimuli, withdrawal latency to radiant heat were tested. After these tests, rats underwent incision of the plantar aspect of the right hindpaw. Guarding pain was measured in separate groups. After a recovery time of 2 hrs, pain behaviors were measured and then again daily for the next 3 days in all groups. After the last test on postoperative day 3, wound appearance was evaluated as described.

Histological examination

In 41 rats, hindpaw tissue was taken and histopathology evaluated. Tissue was removed on postoperative day 3, postfixed with formaldehyde and cryoprotected in a 30% sucrose solution. Sections (40 microns) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) and made permanent. A dermatologist blinded to treatment group then evaluated the slides for overall appearance and apposition using a histologic grade (0= no necrosis, 1= minimal epidermal necrosis/mild inflammation, 2= moderate epidermal necrosis/moderate inflammation, 3= severe epidermal necrosis/severe inflammation).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Data are presented as the median or the mean ± SD where appropriate. The data were compared using non-parametric statistics for the guarding pain, mechanical testing, wound score and histologic evaluation of healing. Friedman’s test for repeated measures and post hoc Mann-Whitney test were used for vehicle vs drug comparisons.18 The Kruskal-Wallis for independent samples and post hoc Dunn’s test were used for comparisons between vehicle and treatment. Heat responses were analyzed using parametric analyses. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was performed. Post hoc t-tests were performed to determine differences between vehicle and treatment groups. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effect of capsaicin infiltration on pain behaviors after incision

Infiltration with 0.025% capsaicin did not affect the mechanical withdrawal threshold 1 day later (Fig. 2A-B). After incision, there were no differences in the withdrawal threshold compared to the vehicle treated group. Compared to vehicle, capsaicin treatment (0.10%) caused a large variance in withdrawal threshold measurements after incision and increased the withdrawal threshold on postoperative day 1 only (Fig. 2C-D).

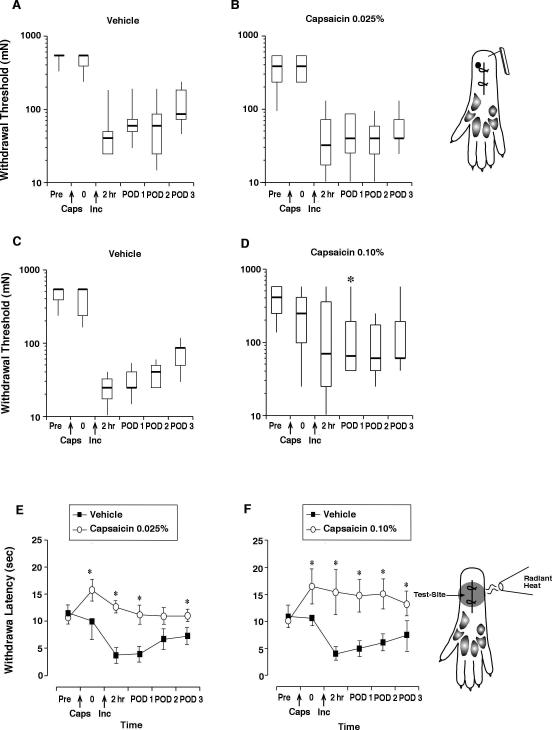

Figure 2.

Pain behaviors to evoked mechanical and heat stimuli in rats treated with capsaicin (or vehicle) infiltration. Withdrawal threshold to the monofilaments in vehicle (n=7) treated rats (A), rats treated with 0.025% (50μg/200μl, n=8) of capsaicin (B), vehicle treated rats (n=7) (C), and 0.10% (200μg/200μl, n=8) of capsaicin (D). The results are expressed as median (horizontal line) with 1st and 3rd quartiles (boxes), and 10th and 90th percentiles (vertical lines). Inset: Diagram of the plantar aspect of the hindpaw and site of application of mechanical stimuli. Withdrawal latency in vehicle treated rats (n=8) or rats treated with 0.025% (n=8) capsaicin (E) and vehicle treated rats (n=8) or after infiltration with 0.10% (n=8) capsaicin (F). Inset: Diagram of the plantar aspect of the hindpaw and site of application of heat. The symbols represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Pre is before injection, 0 is 1 day after injection and before incision. hr=hours, POD=postoperative day. *P<0.05 vs vehicle.

Both 0.025% and 0.10% capsaicin significantly increased the baseline heat withdrawal latency one day after infiltration (Fig. 2E-F). The 0.025% dose attenuated the decrease in heat withdrawal latency in the first and third days after plantar incision, while the 0.10% dose attenuated this response on all 3 days after incision.

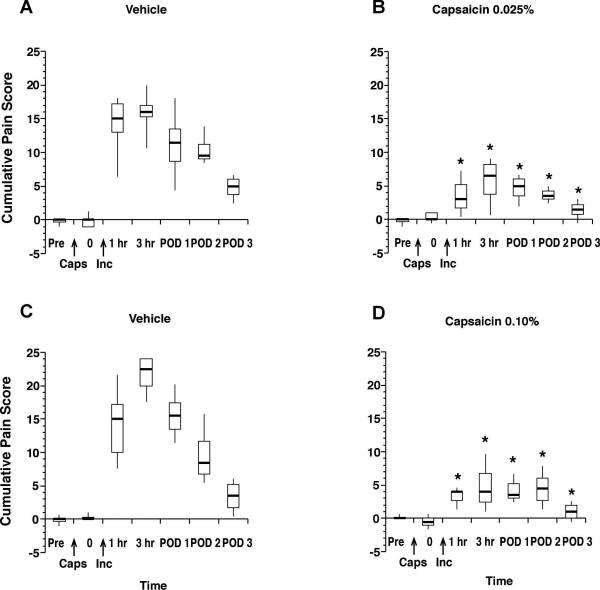

Neither dose of capsaicin caused any changes in guarding pain behavior the next day (i.e., before incision). However, both doses significantly attenuated the increased guarding pain score throughout the 3 days after plantar incision (Fig. 3A-D).

Figure 3.

Guarding pain behavior in rats treated with capsaicin or vehicle infiltration. Cumulative pain score in vehicle (n=8) treated rats (A) or rats treated with 0.025% (50μg/200μl, n=8) capsaicin (B) and in vehicle (n=8) treated rats (C) and after infiltration with 0.10% (200μg/200μl, n=8) of capsaicin (D). The results are expressed as median (horizontal line) with 1st and 3rd quartiles (boxes), and 10th and 90th percentiles (vertical lines). Pre is before injection, 0 is 1 day after injection and before incision. hr=hours, POD=postoperative day. *P<0.05 vs vehicle.

Effect of perineural capsaicin on pain behaviors after incision

Perineural application of 1% capsaicin did not affect the mechanical withdrawal threshold before plantar incision compared to vehicle (Fig. 4. A-B). Two hrs after incision the withdrawal threshold was decreased in both groups; the withdrawal threshold was greater in the capsaicin treated group (Fig 4.A-B). On postoperative days 1 through 3, the withdrawal thresholds were not different between the two groups.

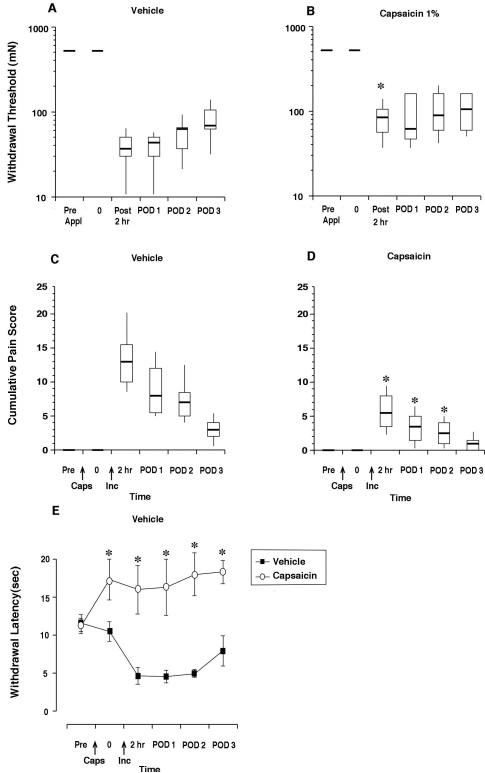

Figure 4.

Pain behaviors after incision in rats treated with perineural capsaicin or vehicle. Withdrawal threshold to the monofilaments in vehicle (n=9) treated rats (A), rats treated with perineural (n=9) capsaicin (B). The results are expressed as median (horizontal line) with 1st and 3rd quartiles (boxes), and 10th and 90th percentiles (vertical lines). Guarding pain behavior in rats treated with perineural vehicle (n=8) (C) or capsaicin (n=8) (D). Withdrawal latency to radiant heat in rats treated with perineural vehicle or capsaicin (E). Pre is before injection, 0 is 4 days after injection and before incision. hr=hours, POD=postoperative day. *P<0.05 vs vehicle.

Perineural capsaicin did not cause any guarding behavior but attenuated the increased guarding response (i.e., cumulative guarding pain score, Fig 4. C-D) caused by incision through postoperative day 2. Perineural capsaicin increased the heat withdrawal latency and prevented the decrease in heat withdrawal produced by plantar incision (Fig. 4E).

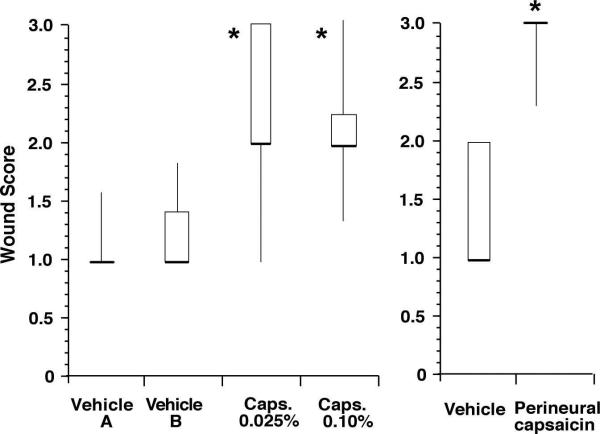

Effect of capsaicin on wound apposition

The effect of capsaicin treatment on wound appearance was characterized numerically after the last behavioral test (Fig. 5). After infiltration of both vehicles, the wound appeared normal and the median score was 1. The median score was 2 in rats that received either 0.025% or 0.10% capsaicin by infiltration. For perineural vehicle application, the median wound score was 1 and in the capsaicin treated group, the median score was 3. Wound appearance was different for capsaicin treatments compared to the respective vehicle treated groups.

Figure 5.

Wound scores in rats treated with capsaicin infiltration or perineural capsaicin (n=7-9 per group). *P<0.05 vs vehicle.The results are expressed as median (horizontal line) with 1st and 3rd quartiles (boxes), and 10th and 90th percentiles (vertical lines).

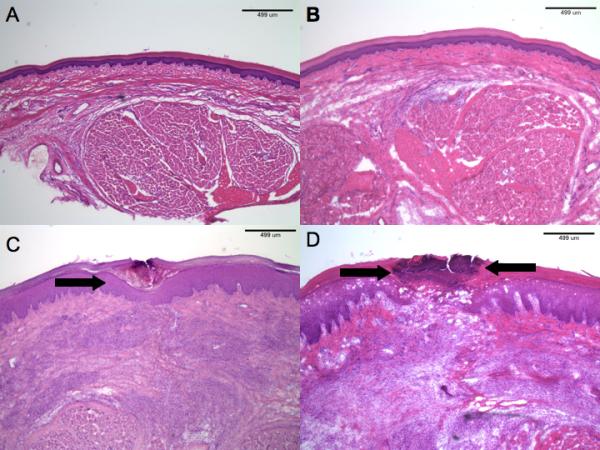

For the normal hindpaw (see example, Fig. 6 A), the median histologic grade was 0 (range = 0). Capsaicin infiltration with 0.025% in sham operated rats resulted in a median histologic grade of 0 (range = 0, see example, Fig 6B) as did the infiltration with 0.10% capsaicin (median=0, range = 0). Incision produced swelling and inflammation of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue on postoperative day 3 in the vehicle treated rats. Typically the epidermis was hypertrophied and apposed (see example Fig. 6C). The median histologic grade was 1 (range = 1). In both groups of capsaicin treated, incised rats, dehiscence and necrosis was evident (see example, Fig. 6D for 0.10% capsaicin). The median histologic grades were 2 (range 2-3) and 3 (range 2-3) for infiltration with 0.025% (P<0.05 vs vehicle) and 0.10% (P<0.05 vs vehicle) capsaicin, respectively.

Fig. 6.

(A) H & E section of normal rat hindpaw. (B) Low-power histopathology of sham-treated hindpaw after (50μg/200μl) was injected. There are no abnormalities. (H & E). (C) Histopathology of incised rats receiving vehicle. Note the superficial scale-crust (arrow), but otherwise normal-appearing epidermis. The dermis shows granulation tissue around the site of incision. (H & E). (D) Incised hindpaw histopathology in a rat receiving subcutaneous capsaicin injection (200μg/200μl). There is pronounced, full-thickness, epidermal necrosis (region between arrows). The dermal findings reveal granulation tissue similar to that observed in vehicle-only treated rats. (H & E).

Discussion

The results of the present study demonstrate that pretreatment with capsaicin, either by infiltration or by proximal perineural application has a differential effect on pain related behaviors caused by plantar incision. Both heat hyperalgesia and guarding pain behaviors were inhibited by capsaicin treatments. Punctate mechanical withdrawal thresholds were only transiently increased by the highest dose of capsaicin, 0.10% (Fig. 2C-D). Dose response evaluation was not determined because two different vehicles were used for the two concentrations of drug.

Wound appearance was influenced by capsaicin infiltration when compared with vehicle controls; but not via its local effects. Both infiltration and perineural application yielded poorly apposed wounds when compared with vehicle controls. This indicates that the attenuation of guarding pain behavior likely leads to damage of the wound because the animals feel less pain and continues to place weight on the paw. In other words, both injections acted upon sensory afferents. Both perineural and local drug administration produced very similar effects on behaviors and wound appearance indicating that the local injection was acting on sensory afferents.

In most studies of analgesia and incision-induced pain behaviors, one pain behavior is tested.8 Few differences in response to analgesics have been noted depending upon the modalities studied and it is assumed that if a treatment influences one behavior it will be analgesic. Conversely, if a treatment has no effect on one modality, it has been assumed that this is a negative result for analgesic properties. The present study demonstrates that an analgesic drug might be overlooked if only one modality is studied.

Previous studies by our laboratory have examined these same pain related behaviors and noted differences in response to analgesic treatments depending upon the behavior measured. For example, guarding pain behavior is more sensitive to morphine since very low doses of morphine (0.03mg/kg) decreased the cumulative pain score for guarding after incision.25 Greater doses (0.3mg/kg) are necessary to inhibit the heat hyperalgesia; only a 1 mg/kg dose inhibited mechanical responses. Interference with the actions of nerve growth factor also influenced certain behaviors.3,28 Using either an antibody or a decoy receptor, absorption of nerve growth factor influenced withdrawal latencies to heat and guarding but not withdrawal threshold to punctate mechanical stimuli.

The concentrations of capsaicin injected locally as analgesic pretreatments in the present study have been tested for inducing pain related behaviors in rodents10 and pain in humans.14,19,20 For example, intradermal injection of capsaicin in concentrations of 0.001 to 1% produced ongoing pain for 8 min and reduced heat pain threshold for approximately 30 min in volunteers. The highest dose was noted to produce an analgesic bleb to mechanical stimuli that persisted for 22 hrs.14 In rats, doses 0.10 to 0.30% produced heat and mechanical hyperalgesia that persisted for up to 4 hrs. The doses used in the present study, 0.025% and 0.10%, are typically lower concentrations than those used to induce persistent hyperalgesia in rodents and humans.

Previous studies by others examined the analgesic properties of capsaicin in the plantar incision model.17 A very high dose of capsaicin was utilized, 1.5%, 15 times our greatest dose. Infiltration with 1.5% capsaicin by itself reduced responses to heat and mechanical stimuli in control unincised rats. In rats pretreated with capsaicin that underwent subsequent incision, both heat and mechanical hyperresponsiveness were inhibited. The authors did not observe any effects on wound healing. Likely, the very high concentration of capsaicin produced additional effects not seen in the present study, perhaps affecting non-TRPV1 expressing nociceptors or perhaps nonneuronal structures. The differential effect of heat and mechanical responses we observed was not reported in study using the high concentration. The lack of effect on wound appearance is surprising given our results.

In another study using the plantar incision, resiniferatoxin, an ultrapotent vanilloid agonist, was administered percutaneously to the sciatic and saphenous nerves before incision.12 Perineural resiniferatoxin prevented the decrease in withdrawal threshold to punctate mechanical stimuli and the exaggerated withdrawal during pressure application. Resiniferatoxin also prevented the decrease in weight bearing and heat hyperalgesia caused by plantar incision. The marked differences in heat and mechanical responses we observed were not reported in the study using resiniferatoxin.

Previous studies have suggested that sensory neuropeptides like substance P and calcitonin gene related peptide contribute to wound healing5,9,22 and others have shown that capsaicin depletes sensory neuropeptides in skin.21 Together these data suggest that capsaicin should modify wound healing by depleting neuropeptides. Several studies have evaluated the effect of capsaicin on wound healing in rats. In some studies, impaired wound healing is noted after capsaicin treatment;11,13 others have not identified an effect of capsaicin.23 In the present study, the appearance and histologic grading of the wounds were influenced by capsaicin. We also demonstrate rats do not guard the incised hindpaw which led to increased weight bearing on the incised plantar surface. This lack of protection of the wound occurs whether the capsaicin is infiltrated at the incision or applied distally to the nerves innervating the plantar surface. Thus, any evaluation of wound healing in the plantar incision model is confounded by the the analgesic effect of the capsiacin treatment because guarding is inhibited producing weight bearing on the wound. The effect of capsaicin on the appearance of the wound is sensory related but our experiments do not demonstrate a role for sensory afferents or neurogenic inflammation in wound healing.

A recent report evaluated the analgesic efficacy of a single intraoperative wound instillation of capsaicin in male patients undergoing open mesh groin hernia repair.1 The cumulative pain score was significantly lower during the first 3 days postoperatively in the capsaicin treated group. No significant adverse events including wound healing were noted in the capsaicin-treated group. The analgesic effect of capsaicin and morphine in postoperative patients and the reduction in guarding pain score by dilute capsaicin and the low doses of morphine in our model suggest that this behavior may translate to clinical postoperative pain, perhaps pain at rest. These human studies also suggest that the effects of capsaicin on wound healing in our model are a result of the marked analgesic effect and the resultant lack of guarding. Clinical barriers still exist in the goal to develop a formulation that would not require general anesthesia prior to infiltration or perineural injection, and that would not require a prolonged general anesthetic so that the early side effects are no longer problematic.24

In a recent report, we described the analgesic effects of a TRPV1 receptor antagonist in the plantar incision. Only a small effect on heat hyperalgesia was noted; guarding and mechanical responses were not affected. Together, these results indicate that TRPV1 containing afferents are critical for guarding pain but the TRPV1 receptor is not. Other receptors on TRPV1 containing afferents must be important.

These results of the present study demonstrate that dilute solutions of capsaicin are selective for their effects on pain related behaviors after plantar incision. Heat and guarding pain are inhibited by capsaicin and share some common mechanisms. Responses to mechanical stimuli utilize a pathway that is less sensitive to capsaicin. Furthermore, these data suggest that when evaluating novel treatments for postoperative pain, studies using a single stimulus modality like mechanical withdrawal threshold, may overlook an analgesic effect by not examining a variety of stimuli.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Brennan has served as a consultant to Anesevia, manufacturer of Adlea (capsaicin) after the completion of the studies. The authors are grateful for the technical assistance of Sung Kung Lee M.D. and Jason Kruger M.D.

Support: This work was performed in the Department of Anesthesia at the University of Iowa and was supported by a grant from University of Iowa to Dr. Gerald F. Gebhart, by Academy of Finland and Oskar Oflund stiftelse to Dr. Minna M. Hamalainen and by National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland grants GM-55831 AND GM-067752 to T.J.B.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aasvang EK, Hansen JB, Malmstrom J, Asmussen T, Gennevois D, Struys MM, Kehlet H. The effect of wound instillation of a novel purified capsaicin formulation on postherniotomy pain: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:282–291. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31816b94c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banik RK, Brennan TJ. Spontaneous discharge and increased heat sensitivity of rat c-fiber nociceptors are present in vitro after plantar incision. Pain. 2004;112:204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banik RK, Subieta AR, Wu C, Brennan TJ. Increased nerve growth factor after rat plantar incision contributes to guarding behavior and heat hyperalgesia. Pain. 2005;117:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berde CB, Brennan TJ, Raja SN. Opioids: More to learn, improvements to be made. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1309–1312. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200306000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brain SD. Sensory neuropeptides: Their role in inflammation and wound healing. Immunopharmacology. 1997;37:133–152. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(97)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan TJ. Incisional sensitivity and pain measurements: Dissecting mechanisms for postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:3–4. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan TJ, Vandermeulen EP, Gebhart GF. Characterization of a rat model of incisional pain. Pain. 1996;64:493–501. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)01441-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan TJ, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. Mechanisms of incisional pain. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2005;23:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.atc.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunnick CA, Gibran NS, Heimbach DM. Substance p has a role in neurogenic mediation of human burn wound healing. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1996;17:390–396. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilchrist HD, Allard BL, Simone DA. Enhanced withdrawal responses to heat and mechanical stimuli following intraplantar injection of capsaicin in rats. Pain. 1996;67:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khalil Z, Helme R. Sensory peptides as neuromodulators of wound healing in aged rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51:B354–361. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.5.b354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kissin I, Davison N, Bradley EL., Jr. Perineural resiniferatoxin prevents hyperalgesia in a rat model of postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:774–780. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000143570.75908.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kjartansson J, Dalsgaard CJ, Jonsson CE. Decreased survival of experimental critical flaps in rats after sensory denervation with capsaicin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79:218–221. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198702000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaMotte RH, Shain CN, Simone DA, Tsai EF. Neurogenic hyperalgesia: Psychophysical studies of underlying mechanisms. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66:190–211. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.1.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pini A, Baranowski R, Lynn B. Long-term reduction in the number of c-fibre nociceptors following capsaicin treatment of a cutaneous nerve in adult rats. Eur J Neurosci. 1990;2:89–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1990.tb00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pogatzki EM, Gebhart GF, Brennan TJ. Characterization of adelta- and c-fibers innervating the plantar rat hindpaw one day after an incision. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:721–731. doi: 10.1152/jn.00208.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pospisilova E, Palecek J. Post-operative pain behavior in rats is reduced after single high-concentration capsaicin application. Pain. 2006;125:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siegel S, Castellan NJ. Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. McGraw-Hill, Inc.; New York: pp. 128–223. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simone DA, Baumann TK, LaMotte RH. Dose-dependent pain and mechanical hyperalgesia in humans after intradermal injection of capsaicin. Pain. 1989;38:99–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simone DA, Ngeow JY, Putterman GJ, LaMotte RH. Hyperalgesia to heat after intradermal injection of capsaicin. Brain Res. 1987;418:201–203. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90982-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simone DA, Nolano M, Johnson T, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Kennedy WR. Intradermal injection of capsaicin in humans produces degeneration and subsequent reinnervation of epidermal nerve fibers: Correlation with sensory function. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8947–8959. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08947.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas DA, Dubner R, Ruda MA. Neonatal capsaicin treatment in rats results in scratching behavior with skin damage: Potential model of non-painful dysesthesia. Neurosci Lett. 1994;171:101–104. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90615-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallengren J, Chen D, Sundler F. Neuropeptide-containing c-fibres and wound healing in rat skin. Neither capsaicin nor peripheral neurotomy affect the rate of healing. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:400–408. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White PF. Red-hot chili peppers: A spicy new approach to preventing postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:6–8. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181753276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu C, Gavva NR, Brennan TJ. Effect of amg0347, a transient receptor potential type v1 receptor antagonist, and morphine on pain behavior after plantar incision. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:1100–1108. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31817302b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zahn PK, Brennan TJ. Primary and secondary hyperalgesia in a rat model for human postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:863–872. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199903000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zahn PK, Gysbers D, Brennan TJ. Effect of systemic and intrathecal morphine in a rat model of postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:1066–1077. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zahn PK, Subieta A, Park SS, Brennan TJ. Effect of blockade of nerve growth factor and tumor necrosis factor on pain behaviors after plantar incision. J Pain. 2004;5:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.02.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmermann M. Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain. 1983;16:109–110. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]