Current guidelines for prescribing lipid lowering drugs are based on an individual's risk of coronary heart disease rather than on the reduction in risk that treatment may bring. We report a strategy for making treatment decisions that combines computer assisted calculation of absolute risk with an estimate of benefit to the patient from treatment.

Subjects, methods, and results

During a period of 14 months, 17 randomly selected general practices (63 practitioners) in north Staffordshire were asked to send to the department of clinical biochemistry their requests for coronary heart disease risk assessment on patients being considered for lipid lowering drug treatment.

We used the Framingham statistical model to estimate a patient's absolute risk of coronary heart disease over five years. The reduction in risk that treatment would bring over the next five years was calculated from the product of the absolute five year risk and the risk reduction observed in clinical trials or meta-analysis. The reduction in risk associated with cholesterol lowering drugs was 0.31,1 which was adjusted for the patient's age in line with a meta-analysis showing less benefit with increasing age.2 The reduction in risk was calculated as the absolute five year risk×0.31×age factor (the age factor=0.02357(a)2−3.719(a)+165.3, where (a)=the patient's age, calculated from2).

A database running on Microsoft Access (version 7 for Windows 95) was developed. This calculated absolute risk, risk reduction (and number needed to treat), and the mean five year risk in the local population for that age and sex.

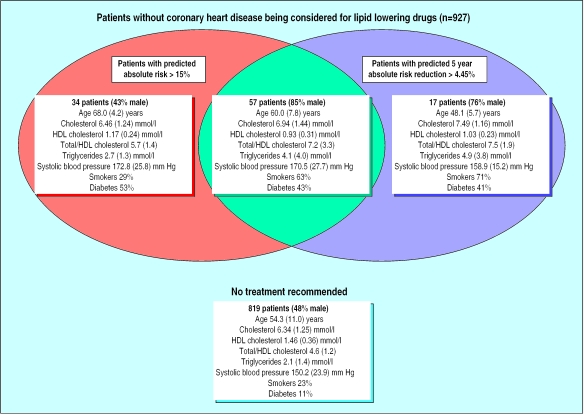

Patients were grouped according to whether they would be recommended for treatment because (a) their absolute risk of coronary heart disease was greater than 15% in five years; (b) treatment would reduce their absolute risk of heart disease by more than 4.45% over five years (equivalent to the treatment benefit in the high risk group in the Scottish study3); or (c) they met both criteria. The Mann-Whitney U test and the χ2 test were used to compare the levels of risk factors in these groups.

We received assessment requests for 1320 patients. Patients with vascular disease, aged over 75 years, or already taking lipid lowering drugs were excluded (393 patients). The remaining 927 patients included 484 men (55%), 247 smokers (27%), and 139 with diabetes (15%). The figure shows the breakdown of risk factors in the groups of patients for whom treatment would be recommended.

Patients recommended for treatment because of absolute risk but not benefit (n=34) were less likely to be hyperlipidaemic than those recommended because of benefit but not risk (n=17). The former group had a lower concentration of total cholesterol (mean difference 0.97 mmol/l, P=0.007); a higher concentration of high density lipoprotein cholesterol (0.14 mmol/l, P=0.05); a lower ratio of total cholesterol to high density lipoprotein cholesterol (1.84, P=0.0007); and a lower concentration of triglycerides (2.2 mmol/l, P=0.04) than patients recommended for treatment on the basis of benefit. They were also older (mean difference 19.9 years, P<0.0001) and tended to have a higher systolic blood pressure (13.9 mm Hg, P=0.09), although fewer of them smoked (29.4% v 70.6%, P=0.005).

Comment

Recommendations based on absolute risk may not achieve the most appropriate prescribing as lipid lowering drugs may be given to patients whose main coronary risk factor is not hyperlipidaemia. By ignoring risk reduction, doctors may miss an opportunity for coronary prevention in younger people whose absolute risk threshold in five years is below 15%. These patients stand to gain more through treatment of their main risk factor (hyperlipidaemia), particularly when this is viewed in the context of their greater life expectancy.

We calculate and report benefit from other measures too, using risk reductions of 16% for antihypertensive drugs,4 22.4% for aspirin,5 and 45% for stopping smoking (a conservative estimate). Reporting a patient's risk reduction for several measures provides doctors with more objective information to help them choose the most appropriate treatment. In addition, computer networking provides an opportunity for national guidelines to be developed and updated along similar lines.

ADDENDUM—The recent analysis of the statin trials by LaRosa (JAMA 1999;282:2340-6), published since this article was accepted for publication, suggests no difference in relative risk reduction in subjects older or younger than 65 years. The conclusion from this analysis may not necessarily apply across the wider age range commonly encountered by those running primary prevention clinics; nevertheless, at this stage more data are required to establish whether the benefits of lipid lowering therapy are age related.

Figure.

Coronary risk factors in patients being considered for lipid lowering drugs. Values are means (SD)

Editorial by Jackson

Footnotes

Funding: North Staffordshire Health authority.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, Isles CG, Lorimer AR, Macfarlane PW, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1301–1307. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Law MR, Wald NJ, Thompson SG. By how much and how quickly does reduction in serum cholesterol lower risk of ischaemic heart disease? BMJ. 1994;308:367–372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6925.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Group. West of Scotland coronary prevention study: identification of high-risk groups and comparison with other cardiovascular intervention trials. Lancet. 1996;348:1339–1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins R, MacMahon S. Blood pressure, antihypertensive drug treatment and the risks of stroke and coronary heart disease. Br Med Bull. 1994;50:272–298. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medical Research Council's General Practice Research Framework. Thrombosis prevention trial: randomised trial of low-intensity oral anticoagulation with warfarin and low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of ischaemic heart disease in men at increased risk. Lancet. 1998;351:233–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]