Abstract

A reorganization of child and family health nursing services followed policy changes in New South Wales, Australia, in the late 1990s. However, the introduction of universal and sustained home visiting to all new parents limited resources available to provide support groups for new parents. This qualitative research study used a case study approach to examine the impact of new parents' group attendance on mothers and on mothers' interactions with their baby. Key findings demonstrated that attendance at a group created an opportunity, the overarching theme, for both the mothers and infants. New Parent groups appear to be as important as other modes of nursing service delivery to children and parents and serve a different purpose to center-based or home visits.

Keywords: new-parent groups, child and family health nurse, partnership

BACKGROUND

Providing a secure attachment for the infant is paramount for the child's ongoing ability to have supportive, sustaining relationships (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Bowlby, 1969, 1973, 1984; Fonagy, 2001b; Karen, 1994; Rutter, 1995). A secure attachment is important for the infant because it “can serve as a protective factor against later emotional and behavioral problems, providing children with greater resilience, less anxiety and hostility and good interpersonal relatedness” (NSW Health, 2008a, p. 9). The emotional sensitivity, availability, and responsiveness of the primary caregiver—in this instance, the mother—plays a pivotal role in providing that security (Barnes, 2003; Fonagy, 2001a; Onunaku, 2005; Sroufe, 1995). Over the last 100 years, child and family nursing services have evolved from the original purpose of reducing infant mortality to a role that promotes the development of this early relationship between the mother and baby in the context of a general primary health-care focus (O'Connor 1989).

Support groups for first-time parents (also known as “New Parent groups”) have been conducted in Australia by child and family health nurses for more than 40 years in order to meet the needs of postnatal women, their partners, and their infant (Carolan, 2004/2005; Gillieatt, Ferroni, & Moore, 1999; Hanna, Edgecombe, Jackson, & Newman, 2002; Lawson & Callaghan, 1991; Scott, Brady, & Glynn, 2001). Parent groups sponsored by child and family health nursing programs aim to be father inclusive. The focus of the current study, however, was on the impact of group attendance on the interactions between the nurse and mothers and between the mothers and their infant. Hence, although the groups are referred to as “New Parent groups,” in the context of the present study, the focus is the participation of the mothers because, as Wilson (2003) noted, mothers are generally responsible for the primary care of their young infant in the early months at home.

Traditionally in New South Wales (NSW), Australia, New Parent groups are led by a nurse, are held weekly for about 2 hours, and cover parenting topics such as child development, infant feeding and sleeping routines, and child safety. Facilitated for 4 to 8 weeks, the groups are generally “closed,” with all participants commencing in Week 1 of the normally six-session group series. Parents are encouraged to attend all sessions. This format for traditional New Parent groups has remained very much the same over the past 30 years in NSW child and family health centers and throughout similar child health nursing services in Australia. However, the number of sessions offered may vary, and contemporary New Parent groups are offered in a partnership approach with participants rather than the nurse appearing as the “expert” (Kruske, Schmied, Sutton, & O'Hare, 2004).

The literature indicates that New Parent groups that are attended predominantly by mothers are beneficial in terms of social support resulting from the opportunity to meet other mothers and to share experiences (Carolan, 2004/2005; Gillieatt et al., 1999; Hanna et al., 2002; Lawson & Callaghan, 1991; Scott et al., 2001). Social support also appears to exert a protective function against depression primarily through the mediation of self-efficacy (Milgrom, Martin, & Negri, 1999; Teti & Gelfand, 1991) and “promote[s] a positive self-evaluation in parenting…mediating the stress of the experience” (Reece, 1993, p. 97). Darbyshire and Jackson (2004/2005) state that it is important for nurses to understand and harness the resilience of families through using a strengths-based approach to build health capacity in families. It is essential that child and family health nurses are available to help and support mothers with their new infant, recognizing the strengths and abilities the mother and her infant bring to their new role. The most effective way for a nurse to proceed in developing a relationship with the mother and her infant is to foster a partnership (Bidmead, Davis, & Day, 2002; Davis, Day, & Bidmead, 2002). Bidmead and Cowley (2005) define the concept of partnership as follows:

Partnership with clients…may be defined as a respectful, negotiated way of working together that enables choice, participation and equity, within an honest, trusting relationship that is based in empathy, support and reciprocity. It is best established within a model…that recognizes partnership as a central tenet. It requires a high level of interpersonal qualities and communication skills in staff who are, themselves, supported through a system of clinical supervision that operates within the same framework of partnership. (p. 208)

Families NSW (formerly known as “Families First”) was launched in New South Wales in 1999 as a collaborative government strategy to provide support networks for families raising children (Cabinet Office, 1999). The NSW Government's various departments devoted to health, education, housing, and community services are the key agencies working in partnership to promote and develop this initiative. Families NSW is an evidence-based strategy that was implemented for families with children aged 0–8 years in response to overwhelming international evidence of the importance of children's early years to their future well-being and adjustment (Heckman, 2006; McCain & Mustard 1999; Olds et al., 1997; Perry, Pollard, Blakely, Baker, & Vigilante, 1995). Under Families NSW, child and family health nurses are viewed as key health professionals responsible for reallocating resources and services to commence universal and sustained home visitations to all new parents (NSW Health, 2008b).

At the time the current study commenced, in order to accommodate the amount of nursing staff required to provide universal and sustained home visitations, the number of New Parent groups offered in one particular regional NSW Child and Family Health Nursing Service declined. Furthermore, it was apparent that mothers were dissatisfied with the reduction and, in other areas, with the cessation of groups (Cartwright & Greig, 2002). Some mothers anecdotally commented that, although the home visits were very “nice,” the visits did not lead to meeting other mothers and making important friendships (Cartwright & Greig, 2002). The inability to provide a group forum for mothers or parents in the Child and Family Health Nursing Service because of limited resources and lack of time resulted in fewer opportunities for mothers/parents to meet together and share their conversations with the child and family health nurse. A further ramification of the reduction of groups was the risk of mothers becoming more isolated because of the lack of access to an important opportunity to socialize and learn about mothering (Barclay, Everitt, Rogan, Schmied, & Wyllie, 1997; Carolan, 2004/2005; Fowler, 2000; Hanna et al., 2002). Langford, Bowsher, Maloney, and Lillis (1997) claim that the positive consequences of social support, as manifested in the literature, are “personal competence, health maintenance behaviors, especially coping behaviors, perceived control, positive affect, sense of stability, recognition of self-worth, decreased anxiety and depression, and psychological well-being” (p. 99).

The protective factors related to social support contribute positively to the mother's concept of parental self-efficacy. De Montigny and Lacharite (2005) define perceived parental self-efficacy as “beliefs or judgments a parent holds of [her or his] capabilities to organize and execute a set of tasks related to parenting a child” (p. 387). Positive parental self-efficacy can act as a protective factor against the development of postnatal mood disorders (Barnett, Fowler, & Glossup, 2004; Milgrom, 1994; NSW Health, 2008a). This is significant because postnatal mood disorders such as depression are known to have adverse outcomes that affect the mother, her infant, and family and friends (Barnett et al., 2004; Milgrom, 1994; NSW Health, 2008a). First-time mothers in NSW can obtain social support by attending a New Parent group at their local Child and Family Health Center.

SUMMARY

Because of the need to redirect scarce resources in child and family health nursing so as to meet Families NSW guidelines for home visiting targets, mothers were potentially “missing out” on the advantages identified as emerging from attendance at New Parent groups. The limitations of the Australian nursing research studies of New Parent groups were apparent in that they were all retrospective in design with attendant risk of recall bias. Furthermore, a literature review did not reveal nursing research conducted using a case-study approach on parenting groups in Child and Family Health Centers in Australia. The purpose of this article is to report on a prospective, qualitative case study that specifically aimed at assessing the impact of this change in service delivery by examining the mothers' views of the impact of attendance at New Parent groups on themselves and on their interactions with their baby.

METHOD

Research Aims

The aims of the present study were to:

assess the impact of participation in a New Parent group on the mothers themselves;

evaluate the mothers' views about the impact of attendance at the New Parent group on their interactions with their baby;

assess the child and family health nurse facilitator's views about the impact of attendance at New Parent groups on mothers and on mothers' interactions with their baby;

inform the content and processes of conducting New Parent groups in Child and Family Health Centers, based on the information derived from the participants.

A qualitative research approach—namely, a case study method—was selected for use in this investigation in order to describe the views of the nurse and first-time mothers regarding the impact of attendance at a New Parent group on the mothers themselves and their views regarding the impact, if any, on the mothers' interactions with their baby. Case study was selected as the most appropriate method for this investigation for a number of reasons. Merriam (1998) states that the case study can be a useful method if the researcher uses process as a focus for the research. Additionally, Merriam (1998) notes that there are two ways to view the case study method. Firstly, the case study can be viewed as a monitoring approach—for example, describing the context and participants of the study. Secondly, the case study method can be viewed as a process for providing causal explanation—that is, for discovering or confirming the process by which the treatment or process had the effect that it did while, at the same time, remaining in the qualitative mode of inquiry. In the present study, both a comprehensive description of the case and the views of the participants were required in order to “discover” the explanation for the impact the New Parent group may have had (if any) on the mothers themselves and on their interactions with their baby. Moreover, the case study method allows for a holistic view of these processes and of the social interactions between the participants.

In the present study, the New Parent group, which comprised the mothers, their infants, and the facilitating nurse, represented a “case” because it was a “specific, unique, bounded system” (Stake, 1995, p. 88). In this study, the case was a particular New Parent group, and qualitative methods of data collection and analysis were used according to the criteria outlined by Stake (1995) and by Creswell (1998). The case study was conducted over a 2-month period in mid-2004.

The Personal Construct Theory (Kelly, 1991) provided the framework for the present study. The Personal Construct Theory is a complex theory that states that people are very much like scientists in that they test and develop theories or constructs in trying to understand, anticipate, and adapt to events. All people bring to relationships a set of constructs or concepts derived from the meanings they have placed on their past experiences. People are different in how they construe events and, therefore, in their behaviors (Kelly, 1991). In the present study, the most useful aspect of the Personal Construct Theory was the capacity to which it could be used to observe and understand how people—in this case, the mothers—developed and changed their constructs about themselves as mothers and in their understanding of their infant's behaviors due to their attendance at the New Parent group.

In this study, it was anticipated that the nurse would facilitate the New Parent group in partnership with the mothers (Bidmead & Cowley, 2005). It was hoped that this modeling of partnership with mothers would be replicated in a parallel process between the mothers themselves (e.g., by showing respect and empathy for one another and between individual mothers and their baby). According to the Personal Construct Theory, an expected outcome of this approach for mothers and their infants was that the mothers would monitor their baby, construe what their baby may be feeling, thinking, or needing, and respond appropriately or otherwise.

Ethics Clearance

The Human Research Ethics Committee of the Hunter Area Health Service and of the University of Newcastle granted ethics clearance for the study. The director of nursing responsible for the services in the location in which the study was conducted also gave written permission for the study to proceed.

Recruitment

Child and family health nurse.

An outline of the proposed study was provided at an information session that was organized with a group of local child and family health nurses from the region in which the study was to be conducted. Although only one nurse facilitator was required for the study, an opportunity was provided to all the child and family health nurses to participate. One child and family health nurse was recruited shortly after the information session.

Parents and infants.

Eligible, first-time mothers with a singleton baby younger than 4 months of age who attended the Child and Family Health Center at which the participating nurse worked or who attended a nearby center and wished to participate in a New Parent group were informed of the study by the recruited child and family health nurse. The nurse provided the first author with the telephone contact details of the mothers who expressed interest in participating in the study. The first author telephoned these mothers and provided them with a fuller description of the purpose and process of the study.

The husband of one of the participating mothers also wished to attend the group and participate in the study. The original proposal and ethics clearance did not anticipate this request from a father. Nevertheless, submission of a variation to the study to the ethics committees resulted in permission being granted for this father's inclusion in the study. Although the focus of the study remained on the mothers and the impact of the New Parent group on the mothers' interactions with their infant, data relating to this particular father's role in the group were included in the analysis.

The group was created after a sufficient number of mothers and their infants volunteered to participate in the study. The number was initially estimated to be between 5 and 10 mother/infant pairs. A New Parent group generally comprises this same number of first-time mothers, their infants, and the facilitating nurse. Five first-time mothers who met the study's inclusion criteria consented to participate; however, one mother dropped out due to personal circumstances. Ultimately, the participants comprising this case study included one child and family health nurse group facilitator, four participating first–time mothers, one father, and four infants aged between 2 and 6 weeks at the beginning of the group. The mothers were aged between 24 and 32 years. All of the mothers were in long-term married or de facto relationships and had been in full-time employment up until the birth of their baby. Three of the mothers were of Anglo-Celtic origin; the fourth mother's family of origin was from South Asia. The nurse stated that she had facilitated successful New Parent groups in the past with just four mothers and their infants and was confident that the participants in this group would get along well together and that the group would be successful.

The participating child and family health nurse facilitated all of the six group sessions. One mother attended all six sessions. The remaining three mothers attended five sessions, and the father attended three sessions. Importantly, all of the mothers attended the first and last sessions of the New Parent group. These two sessions are particularly important because the initial session “sets the scene,” and the final group session includes planning for group members to meet after the group's formal closure.

This study took place in two locations. The central location for the group as a whole was a Child and Family Health Center in a regional area of NSW, Australia. The second location for the study was in the participating mothers' homes. The mothers were familiar with nurses visiting at their home because all had had a universal health home visit already conducted by a child and family health nurse.

Data Collection

Case study method uses multiple sources of information in data collection (Creswell, 1998). The data in the present case study were collected from two main sources: semistructured interviews and participant observation. Interviews for both the nurse and the mothers were audio taped with their permission, and participants were invited to review the transcriptions of their tape. The participating child and family health nurse was interviewed on two occasions: once prior to commencing the group and a second time at the conclusion of the group to obtain her views as well as examples of the impact, if any, of the group on the mothers and on their interactions with their baby.

All three interviews with each mother were held in the privacy of her own home. Semistructured interviews conducted with participating mothers prior to the commencement of the group helped to identify the mothers' expectations of what might occur in the group and what they hoped to gain for themselves and their baby by attending. Further interviews were held with the mothers between the third and fourth weekly sessions of the group and at the conclusion of the group series.

At each of the six group sessions, data were collected through field notes written either during or after each group session. Data consisted of conversations between participants, processes observed in the group, and observation of social interactions between the mothers, their babies, and the nurse. This triangulated method was used to enable a comprehensive, in-depth study of the “case” (Bryar, 1999; Elliott, 2003).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed thematically, using approaches recommended by Stake (1995) and by Creswell (1998). According to Stake (1995), “Often…patterns [themes] will be known in advance, drawn from the research questions, [and] serve as a template for the analysis” (p. 78), as was the case in the present study. Additionally, Creswell (1998) recommends including a “description of the case, a detailed view of aspects about the case—the facts” (p. 154). This additional layer assists with the naturalistic generalization the reader may glean from having a thorough account available of the history, setting, participants, methods of data collection and analysis, and the assertions of findings and recommendations derived from the case. The naturalistic generalization allows the case to ring either true or false to the reader no matter whether the reader has knowledge of the content of the case or not.

In the present case study, rigor was achieved through a variety of means. Credibility (Beck, 1993) was achieved through providing a significantly thick description of the case, which permitted naturalistic generalizations (Stake, 1995) to occur for readers. Auditability (Beck, 1993) was attained through providing a comprehensive account of methods of recruitment, data collection, and data analysis of the case. Fittingness (Beck, 1993) or transferability was achieved through the provision of literature that reflected similarities to the themes from the findings of this case, thereby enhancing the probability that “the research findings have meaning to others in similar circumstances” (Chiovitti & Piran, 2003, p. 433). Providing thick description also aids in transferability and generalizability of the study (Tuckett, 2005).

Stake (1995) recommends triangulation and member checking to enhance the quality of findings in case study research. Methodological triangulation can be achieved through the combination of dissimilar techniques of data collection about the same phenomenon (Tuckett, 2005), which was ensured in the present study through the use of interviews and participant observation. Only the nurse chose to review her interview responses in this study, while the mothers declined the offer to review or edit their interview transcripts.

FINDINGS

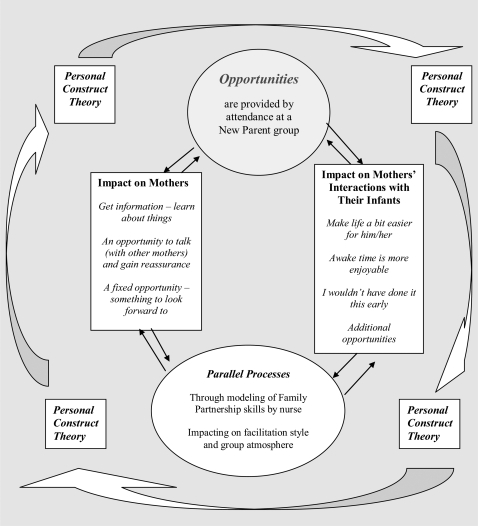

Key findings from the case study demonstrate that attendance at a New Parent group created an overarching theme of opportunities for both the mothers and their infants that they otherwise may not have had. Themes (identified here in italics) derived from the data for the impact of group participation on the mothers were identified by using the participants' words and indicated that group participation enabled opportunities for the mothers to obtain information and learn about things and to talk to other mothers and meet people who were going through the same thing and gain reassurance. Attendance provided a fixed opportunity and something to look forward to each week.

Four themes were found regarding the impact of group attendance on the mothers' interactions with their infant. Using the mothers' phrasing for the first three themes, the findings indicate that attendance helped make life a bit easier for him/her [baby], awake time [with baby] is more enjoyable, and I wouldn't have done it [new activity with baby] this early. The fourth theme derived from the analysis was additional opportunities. The nurse's facilitation style and modeling of Family Partnership skills impacted positively on the group atmosphere and outcomes for the mothers and their infant. (See the Figure for an illustration of the major themes and findings of this case study.)

Figure.

Major themes and findings of case study

DISCUSSION

Impact on Mothers of Attendance at the New Parent Group

Attendance at the New Parent group in this case study provided the mothers with three key opportunities. These three opportunities were to be able to get information / learn about things, to have an opportunity to talk [with other mothers] and gain reassurance, and to have a fixed opportunity [and] something to look forward to each week.

Each of the three themes is consistent with findings from two Australian nursing studies regarding the reasons women give for initially attending New Parent groups as well as the benefits they receive from attending (Gillieatt et al., 1999; Scott et al., 2001). These three key opportunities provided positive mental health benefits to the participants in the present study through ready access to social support at a time of significant transition in their lives. The study demonstrated that the opportunities derived from group attendance also had a direct benefit on the mothers' mental health by increasing their feelings (and constructions) of confidence, competence, and self-efficacy in the mothering role. These findings are consistent with the literature on the benefits of New Parent groups (Carolan, 2004/2005; Gillieatt et al., 1999) and the benefits of positive parental self-efficacy (Barnett et al., 2004; Milgrom, 1994; Milgrom et al., 1999).

The participants in this case study also reported that they learned from each other and that the discussions and information sharing were valuable in providing reassurance and in normalizing what was happening with their infant.

Opportunities and the Importance of Early Intervention and Fostering a Secure Attachment Between Mothers and Their Infants

It is evident from this study that New Parent groups offer first-time mothers and their infants valuable opportunities at a time of key transition in their lives. These opportunities include promotion and modeling by the nurse of sensitive and responsive caregiving that in turn promotes maternal sets of constructions such as parental self-efficacy, facilitation of realistic expectations of motherhood, and insight into and understanding of infant cues, development, and behaviors (Davis et al., 2002). In offering a New Parent group to first-time parents, the nurse in the present study created an opportunity for early intervention at the key life transition point of early parenthood in order to build on the mothers' personal and family strengths. Assisting first-time mothers to understand and care for their new baby and foster secure attachments with their infant is one of the most important tasks of child and family health nurses.

Postnatal Care

Consistent with the literature, attendance at this study's New Parent group appeared to meet some of the mothers' perceived needs for postnatal care and postnatal services. Findings from previous studies have indicated that primiparas have a greater need for help and prefer information on baby-care topics (Borjesson, Paperin, & Lindell, 2004; Moran, Holt, & Martin, 1997) and that mothers seek personalized information, support, and organization of services that facilitate contact and interaction with other mothers (Butchart, Tancred, & Wildman, 1999; Fagerskiold & Ek, 2003; Plastow, 2000), all of which were available from the local Child and Family Health Nursing Service. Attendance at the group enabled the mothers to ask questions and to interact.

Impact on the Mothers' Interactions With Their Infant From Attendance at the New Parent Group

Similar to nursing research conducted in the United States, Scotland, and Scandinavia (Abriola, 1990; Fagerskiold, Wahlberg, & Ek, 2001; Gordon, Robertson, & Swan, 1995; Jarvinen et al., cited in Tarkka, 2003), Australian studies to date relating to New Parent groups have largely focused on the benefits derived by participating mothers (Carolan, 2004/2005; Gillieatt et al., 1999; Hanna et al., 2002; Lawson & Callaghan, 1991; Scott et al., 2001). The infants in all of these studies received little attention, except that two Australian studies commented on a long-term benefit for the children being in contact with others (Scott et al., 2001) and having access to children of a similar age (Carolan, 2004/2005).

In the present case study, the participating nurse's and the mothers' views about the impact of the group on the mothers' interactions with their infant was sought at each interview. Observations of these interactions were also conducted at each of the six group sessions. This information had not been previously sought by nursing researchers studying New Parent groups. Within the overarching theme of opportunities, a number of subordinate themes were evident. The first three subthemes were titled (using the mothers' own phrasing) make life a bit easier for him/her [baby], awake time [with baby] is more enjoyable, and I wouldn't have done it this early. In the third subtheme, I wouldn't have done it this early, “it” refers to new activities the mothers introduced to their baby, such as reading, as well as the earlier focus that group attendance fostered in gaining knowledge about infant safety prevention activities that correlated with their infant's increasing mobility. The mothers stated they would not have thought of these issues as early if they had not heard about them at the group. A further subtheme derived from the analysis was additional opportunities.

The impact of attendance on the mothers' interactions with their baby and the benefits the mothers believed their baby received were closely intertwined with the benefits the mothers perceived they had gained themselves. For example, the mothers' general increase in parental self-efficacy through increased parenting knowledge, competence, and confidence from attendance at the group had a direct impact on their baby, thereby making life easier for him/her, creating an ability to have more fun during awake time, and allowing the mothers to commence activities such as reading earlier than they would have anticipated had they not attended the group. These findings are heartening in that enhanced parental abilities have a direct, positive affect on the baby's cognitive ability and mental health and well-being. For example, simple encouragement of the mothers to read and talk to their baby in infancy is known to increase the baby's language acquisition, which is fundamental to enhancing the development of other cognitive abilities (Hawley & Gunner, 2000), and provides a time of closeness and bonding (Fox, 2004). Findings from the current study also identified that participation in the New Parent group enabled mothers to increase their ability to maximize the use of their baby's awake time through learning about play and communication. The literature unequivocally demonstrates that it is crucial for parents to be able to sensitively think about and respond to the thoughts, emotions, and desires of their baby (Fonagy, 2001a; Onunaku, 2005; Sroufe, 1995). In turn, the baby begins to develop a sense of self, learns to self-regulate his/her behaviors, and begins the process of development of his/her internal working model of relationships through the reinforcement of these positive experiences (Mares, Newman, & Warren, 2005).

Through attendance at the New Parent group, the mothers in the present study gained practical information about their baby's development and behaviors from sharing information and observing other mothers interacting with their baby. The richness of this incidental learning (Fowler & Lee, 2004) enabled the mothers to compare and contrast their own baby's behavior and, accordingly, to adjust their own particular style of parenting. It also enabled them to build an understanding of and respond more accurately to their baby's constructions and behavior and to develop realistic personal constructs about themselves as mothers and about their baby's skills and abilities.

Nursing and Working in Partnership

At the start of this study, the participating nurse commented that recent attendance at Family Partnership training had resulted in her modifying her nursing practice. During the study, she was observed displaying the techniques and qualities of a skilled helper (Egan, 2002) and striving to work in partnership with the parents (Bidmead & Cowley, 2005). The fundamental qualities of a skilled helper include respect, genuineness, humility, empathy, quiet enthusiasm, and personal integrity (Davis et al., 2002). In order to demonstrate these qualities, the skilled helper also requires the basic communication skills of attending and active listening (Egan, 2002). The mothers in the present study expressed appreciation of their relationship with the nurse, whom they felt was readily accessible and open to their questions. They also appreciated the nurse's partnership approach because of the influence on the way the group was facilitated—that is, the open recognition of the complementary expertise each member brought to the group, the opportunity for plenty of open group discussion, and respectful valuing of each others' contributions. Further observation identified that the mothers learned from the nurse's role modeling of a partnership approach (see the Figure) and replicated the partnership approach with other mothers in the group.

CONCLUSION

This case study casts new light onto the value and impact that New Parent groups have on mothers and on their interactions with their infant. The strength of the study lies in its rich description of the process and interactions that occur at a New Parent group and its highlight of the value of the nurse's ability to work in partnership from a strengths perspective with participants, both mothers and babies in the group. The prospective study design, using a case study approach, was novel and lent weight to the credibility of the findings because of their being free of recall bias.

Limitations to the study included its small size and the under-representation of subgroups of mothers, such as non-English speaking women, adolescents, Aboriginal women, and women from a low-income bracket. The focus of this study was on mothers and their infants; consequently, there was minimal participation by fathers or active investigation of the impact of attendance at the group on fathers or of the impact attendance may have had, if any, on fathers' interactions with their infant.

For many years, Child and Family Health Nursing Services in NSW and equivalent services elsewhere in Australia and overseas have offered postnatal New Parent groups to first-time parents in the community. In Australia, nurses and mothers have expressed a high acceptability of the traditional format of these groups, as was the case in this study. The findings from this study have been presented at the local service level and at a child and family health nursing professional conference held in NSW (Guest, 2005). Groups for new parents continue to be offered in most health services in NSW despite the expanding and complex role of the contemporary child and family health nurse. The findings from this and similar studies help to legitimize this important health and social support promoting activity by nurses. Child and family health nurses now also offer, to varying degrees, other types of groups for the differing needs of parents, such as Early Bird groups (Kruske et al., 2004), toddler groups, breastfeeding support groups, and postnatal depression therapeutic groups.

New Parent groups appear to be as important as other modes of child and family health nursing service delivery and serve a different purpose to center-based or home visits. New Parent groups should continue to be available and accessible to first-time mothers and their infants in their local community. A vital key to the successful continuation of these groups is the manner in which the groups are facilitated. Nurses facilitating New Parent groups require expertise in generic group facilitation skills as well as an ability to work in partnership with group participants and from a strengths perspective with parents. Nurses who wish or are requested by managers to facilitate these groups should undertake a group training and assessment package that includes an assessment of competency in group facilitation knowledge and skills, including the ability to work in partnership with group participants. It is also recommended that child and family health nurses receive ongoing education in perinatal and infant mental health, infant neurobiology and brain development, and attachment theory, as well as skills and techniques to enhance positive parent-infant interactions.

References

- Abriola DV. Mothers' perceptions of a postpartum support group. Maternal-Child Nursing Journal. 1990;15(2):113–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1978. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Barclay L, Everitt L, Rogan F, Schmied V, Wyllie A. Becoming a mother – An analysis of women's experiences of early motherhood. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25(4):719–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-1-1997025719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J. Interventions addressing infant mental health. Children & Society. 2003;17:386–395. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett B, Fowler C, Glossup P. (3rd ed.) Sydney, Australia: Bryanne Barnett; 2004. Caring for the family's future: A practical guide to identification and management of perinatal anxiety and depression. [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT. Qualitative research: The evaluation of its credibility, fittingness, and auditability. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1993;15:263–266. doi: 10.1177/019394599301500212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidmead C, Cowley S. A concept analysis of partnership with clients. Community Practitioner. 2005;78(6):203–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidmead C, Davis H, Day C. Partnership working: What does it really mean? Community Practitioner. 2002;75(7):256–259. [Google Scholar]

- Borjesson B, Paperin C, Lindell M. Maternal support during the first year. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;45(6):588–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Middlesex, UK: Penguin Books; 1969. Attachment and loss (Vol. 1) [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. New York: Basic Books; 1973. Attachment and loss: Separation, anxiety and anger (Vol. 2) [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Caring for the young: Influences on development. Parenthood: A psychodynamic perspective (pp. 269–285) In: RS Cohen, BJ Cohler, SH Weissman., editors. New York: The Guildford Press; 1984. In. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Bryar RM. An examination of case study research. Nurse Researcher. 1999;7(2):61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Butchart WA, Tancred BL, Wildman N. Listening to women: Focus group discussions of what women want from postnatal care. Curationis. 1999;22:3–8. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v22i4.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office. New South Wales: Government; 1999. Families First – An initiative of the NSW Government: A support network for families raising children. [Google Scholar]

- Carolan M. Maternal and child health nurses: A vital link to the community for primiparae over the age of 35. Contemporary Nurse. 2004/2005;18(1–2):133–142. doi: 10.5172/conu.18.1-2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright L, Greig J. Merewether: Our experience of change. Paper presented at the Families First Child and Family Health Nurses' Forum, Country Comfort Motel, Monte Pio, Maitland, New South Wales, Australia 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Chiovitti RF, Piran N. Rigour and grounded theory research. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;44(4):427–435. doi: 10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. [Google Scholar]

- Darbyshire P, Jackson D. Using a strengths approach to understand resilience and build health capacity in families. Contemporary Nurse. 2004/2005;18(1–2):211–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H, Day C, Bidmead C. London: The Psychological Corporation Limited; 2002. Working in partnership with parents: The parent adviser model. [Google Scholar]

- de Montigny F, Lacharite C. Perceived parental efficacy: Concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;49(4):387–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan G. (7th ed.) Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 2002. The skilled helper: A problem-management and opportunity – Development approach to helping. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D. Approaches to research. Nursing research: Methods, critical appraisal and utilisation (2nd ed., pp. 21–37) In: Z Schneider, D Elliott, C Beanland, G LoBiondo-Wood, J Haber., editors. Marrickville, New South Wales: Mosby; 2003. In. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Fagerskiold AM, Ek AC. Expectations of the child health nurse in Sweden: Two perspectives. International Nursing Review. 2003;50(2):119–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2003.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerskiold AM, Wahlberg V, Ek AC. Maternal expectations of the child health nurse. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2001;3(3):139–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2001.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P. New York: Other Press; 2001a. Attachment theory and psychoanalysis. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P. Early intervention & prevention: The implications of secure and insecure attachment. Paper presented at the Conference on Attachment and Development: Implications for Clinical Practice, Sydney, Australia 2001b [Google Scholar]

- Fowler C. Producing the new mother: Surveillance, normalisation and maternal learning. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Technology, Sydney 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Fowler C, Lee A. Re-writing motherhood: Researching women's experience of learning to mother for the first time. The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;22(2):39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox M. Sydney, Australia: Pan Macmillan Australia; 2004. Reading magic: How your child can learn to read before school – and other read aloud miracles. [Google Scholar]

- Gillieatt S, Ferroni P, Moore J. The difference between sanity and the other: A study of postnatal support groups for first-time mothering. Birth Issues. 1999;8(4):131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J, Robertson R, Swan M. “Babies don't come with a set of instructions”: Running support groups for mothers. Health Visitor. 1995;68(4):155–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest E. New parent groups in child & family health nursing: What is the impact of attendance on mothers and on mothers' interactions with their infants? Preliminary findings. Paper presented at the Tresillian Conference, Homebush, New South Wales, Australia 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Hanna B, Edgecombe G, Jackson CA, Newman S. The importance of first-time parent groups for new parents. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2002;4(4):209–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2002.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley T, Gunner M. (2nd ed.) Chicago: Ounce of Prevention Fund and ZERO TO THREE; 2000. Starting smart: How early experiences affect brain development. Retrieved April 7, 2009, from http://www.zerotothree.org/site/DocServer/startingsmart.pdf?docID=2422. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman J. The economics of investing in early childhood. Presentation to the NIFTeY conference in Sydney, Australia. 2006 Retrieved March 12, 2009, from http://niftey.cyh.com/library/Heckman%20talk%202006-02-08.pdf.

- Karen R. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. Becoming attached: First relationships and how they shape our capacity for love. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly G. Vol. 1. London: Routledge; 1991. The psychology of personal constructs: A theory of personality. [Google Scholar]

- Kruske S, Schmied V, Sutton I, O'Hare J. Mothers' experiences of facilitated peer support groups and individual child health nursing support: A comparative evaluation. The Journal of Perinatal Education. 2004;13(3):31–38. doi: 10.1624/105812404X1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford CPH, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, Lillis PP. Social support: A conceptual analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25(1):95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JS, Callaghan A. Recreating the village: The development of groups to improve social relationships among mothers of newborn infants in Australia. Australian Journal of Public Health. 1991;15(1):64–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1991.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares S, Newman L, Warren B. Camberwell, UK: Acer Press; 2005. Clinical skills in infant mental health. [Google Scholar]

- McCain M, Mustard J. Toronto, Ontario: The Canadian Institute of Advanced Research; 1999. Reversing the real brain drain: Early years study final report. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam SB. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1998. Qualitative research and case study applications in education: Revised and expanded from case study research in education. [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom J. Mother-infant interactions in postpartum depression: An early intervention program. The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1994;11(4):29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom J, Martin P, Negri L. West Sussex, UK: Wiley; 1999. Treating postnatal depression: A psychological approach for health care practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- Moran CF, Holt V, Martin D. What do women want to know after childbirth? Birth (Berkeley, Calif.) 1997;24(1):27–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1997.tb00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NSW [New South Wales] Health. North Sydney, Australia: NSW Department of Health; 2008a. Supporting Families Early – Safe Start guidelines: Improving mental health outcomes for parents and infants. [Google Scholar]

- NSW [New South Wales] Health. North Sydney, Australia: NSW Department of Health; 2008b. Families NSW – Supporting Families Early: Maternal and child health home visiting policy – Primary health care. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor K. Sydney, Australia: NSW Department of Health; 1989. Our babies – The state's best asset: A history of 75 years of baby health services in New South Wales. [Google Scholar]

- Olds D, Eckenrode J, Henderson C, Kitzman H, Powers J, Cole R, et al. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect: Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onunaku N. Los Angeles: National Center for Infant and Early Childhood Health Policy; 2005. Improving maternal and infant mental health: Focus on maternal depression. [Google Scholar]

- Perry B, Pollard R, Blakely T, Baker W, Vigilante D. Neurobiology of adaptation and “use-dependent” development of the brain: How “states” become “traits.”. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1995;16(4):271–289. [Google Scholar]

- Plastow E. Comparing parent and health visitors' perceptions of need. Community Practitioner. 2000;73(2):473–476. [Google Scholar]

- Reece SM. Social support and the early maternal experience of primiparas over 35. Maternal-Child Nursing Journal. 1993;21(3):91–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Maternal deprivation. Handbook of parenting. In: MH Bornstein., editor. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1995. In. (Ed.) (Vol. 4, pp. 3–33) [Google Scholar]

- Scott D, Brady S, Glynn P. New mother groups as a social network intervention: Consumer and maternal and child health nurse perspectives. The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;18(4):23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe AL. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1995. Emotional development: The organization of emotional life in the early years. [Google Scholar]

- Stake RE. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. The art of case study research. [Google Scholar]

- Tarkka MT. Predictors of maternal competence by first-time mothers when the child is 8 months old. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;41(3):233–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, Gelfand DM. Behavioral competence among mothers of infants in the first year: The mediational role of maternal self-efficacy. Child Development. 1991;62(5):918–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckett AG. Part II: Rigour in qualitative research: Complexities and solutions. Nurse Researcher. 2005;13(1):29–42. doi: 10.7748/nr2005.07.13.1.29.c5998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HV. Paradoxical pursuits in child health nursing practice: Discourses of scientific motherhood. Critical Public Health. 2003;13(3):281–293. [Google Scholar]