Abstract

Background: This study reports the results of hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) with floxuridine (FUDR) and dexamethasone (dex) in patients with unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and investigates dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) assessment of tumor vascularity as a biomarker of outcome.

Patients and methods: Thirty-four unresectable patients (26 ICC and eight HCC) were treated with HAI FUDR/dex. Radiologic dynamic and pharmacokinetic parameters related to tumor perfusion were analyzed and correlated with response and survival.

Results: Partial responses were seen in 16 patients (47.1%); time to progression and response duration were 7.4 and 11.9 months, respectively. Median follow-up and median survival were 35 and 29.5 months, respectively; 2-year survival was 67%. DCE-MRI data showed that patients with pretreatment integrated area under the concentration curve of gadolinium contrast over 180 s (AUC 180) >34.2 mM·s had a longer median survival than those with AUC 180 <34 mM·s (35.1 versus 19.1 months, P = 0.002). Decreased volume transfer exchange between the vascular space and extracellular extravascular space (−ΔKtrans) and the corresponding rate constant (−Δkep) on the first post-treatment scan both predicted survival.

Conclusions: In patients with unresectable primary liver cancer, HAI therapy can be effective and safe. Pretreatment and early post-treatment changes in tumor perfusion characteristics may predict treatment outcome.

Keywords: DCE-MRI, HAI FUDR, hepatocellular carcinoma, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) account for nearly all primary liver cancers (PLC) and have become major public health problems [1, 2]. Resection is the most effective therapy for both tumors but is frequently not possible, often because of advanced intrahepatic disease [3, 4]. Patients with irresectable tumors have a poor prognosis, which is marginally improved with ablative or systemic therapies [5–12].

More effective treatment is clearly needed. Liver-directed chemotherapy, administered through a surgically implanted pump, is an attractive option because it allows continuous infusion directly into the arterial bed from which the tumor derives nearly all of its blood supply. Floxuridine (FUDR) is typically used for hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) therapy because of its superior hepatic first-pass metabolic profile [13], exposing hepatic tumors to much higher drug concentrations with little or no systemic toxicity. Although FUDR-based HAI chemotherapy has been used mainly for hepatic colorectal metastases [14, 15], its safety profile is well established and it is known to have activity against PLC [16, 17].

This study investigates HAI FUDR/dexamethasone (dex) for advanced PLC and a potential role for dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) as a biomarker of treatment outcome. DCE-MRI noninvasively assesses the tumor microvasculature, allowing quantitative and semiquantitative measurements of kinetic parameters related to perfusion and permeability [18]. DCE-MRI thus provides a more comprehensive assessment of tumor physiology than is possible with standard imaging. Prior work suggests that DCE-MRI may better assess tumor response than traditional measures of tumor size and that pretreatment parameters and early post-treatment changes may predict outcome [19–22]; however, to date, most studies have shown the utility of DCE-MRI as a pharmacodynamic marker only [23, 24].

patients and methods

eligibility, evaluation, and follow-up

All patients had confirmed and measurable ICC or HCC; irresectability was confirmed by attending hepatobiliary surgeons. Exclusionary factors included the following: extrahepatic metastases at any site or ≥70% liver involvement by tumor; prior hepatic radiation or treatment with FUDR; Karnofsky performance status (KPS) < 60; first-degree sclerosing cholangitis; Gilbert's disease; portal hypertension; severe hepatic parenchymal dysfunction [encephalopathy, serum albumin <2.5 g/dl, serum bilirubin ≥1.8 mg/dl, or international normalized ratio (INR) >1.5)]; portal inflow occlusion; white blood cell <3500 cells/mm3; concurrent malignancy (except localized basal or squamous cell skin cancers); active infection; and pregnant or lactating females. Failure of prior therapy and chronic hepatitis and/or Child–Pugh class A cirrhosis were allowed. All patients were ≥18 years of age and provided informed consent; the protocol and informed consent were approved by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Pretreatment evaluation included a complete history/physical examination, routine laboratory studies, and tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, α-fetoprotein, and CA19-9). Disease extent was assessed with cross-sectional imaging of the chest [computed tomography (CT) scan] and abdomen/pelvis (CT or MRI); suspicious extrahepatic findings were evaluated with targeted imaging (2-[fluorine-18]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography or bone scan) or a biopsy. Patients with presumed ICC also underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, and mammography (females). All patients were required to have hepatitis serology within 52 weeks of treatment (if never previously tested or if previously negative for hepatitis B or C).

Pump placement technique has been reported [25]; tumor and liver biopsies were carried out as part of the procedure. Pretreatment MRI scans were carried out with conventional and dynamic sequences and were repeated every 2 months. The RECIST criteria were used to categorize responses [26], based on tumor size measurements on conventional MRI sequences and confirmed by the study radiologist (LHS).

dynamic MRI

DCE-MRI scans were obtained using a 1.5 Tesla MRI scanner (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI) and an 8-channel phased array body coil. Anatomical images, fat-suppressed T1- and T2-weighted images, three-dimensional T1-weighted pre- and postcontrast images, and fast gradient echo-based perfusion images were acquired during each scan. Paramagnetic contrast (gadolinium diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid; Magnevist, Berlex Inc., Wayne, NJ) was administered at a constant dose of 0.1 mmol/kg body weight. A bolus of gadolinium was injected with a delay of 6 s using an automatic injector (Medrad, Inc., Warrendale, PA) and serial images with a temporal resolution of 1.2–1.5 s were acquired over 4–5 min under shallow breathing conditions. One coronal oblique plane was prescribed through the center of the tumor and the aorta to maximize the cross-sectional area and the temporal resolution. DCE-MRI parameters included the following: echo time (TE) = 2 ms, repetition time (TR) = 9 ms, flip angle = 30°, slice thickness = 7 mm, matrix size = 256 × 128, field of view = 320 mm, band width = 23.8 kHz, number of excitations = 1.0, and number of phases (n) = 225.

Dynamic images were analyzed with a two-compartment general kinetic model using a vascular space (VS) and an extracellular extravascular space (EES) for pharmacokinetic characterization of tumors [27]. The vascular input function (VIF) was measured in some patients, and an average VIF with two fast and slow components [28–30] was used for analysis (Cine Research Software, GEMS, Waukesha, WI) of the dynamic and pharmacokinetic parameters. The variables measured included the following: (i) those related to tumor permeability—the volume transfer constant (Ktrans, 1/min) from VS to EES, the rate constant (kep, 1/min) from EES to VS, the fractional volume of EES (ve); (ii) those related to global tumor perfusion—the integrated area under the concentration curve of gadolinium contrast agent over 90 and 180 s from the start of contrast enhancement (AUC 90 and AUC 180, mM·s) [31]. In each case, region of interest (ROI) and voxel (Vx) analyses were carried out for determining the kinetic parameters in tumors. For the Vx analyses, the top decile values within the ROI were determined for the variables of interest [32–34]. The change in DCE-MRI parameters from baseline to the first post-treatment scan was also determined using both ROI and Vx values.

chemotherapy administration and toxicity

HAI chemotherapy was initiated no sooner than 2 weeks after pump placement, on a 4-week cycle; concurrent systemic chemotherapy was not used in any patient while on protocol. Infusion of HAI FUDR (0.16 mg/kg × 20/pump flow rate) and dex 25 mg started on day 1 of each cycle, with heparin sulfate (30 000 U) and saline added to a volume of 30 ml. On day 14, the residual volume was removed and heparin–saline (30 ml) instilled. Toxicity was graded according to the National Cancer Institute, Common Toxicity Criteria; FUDR dose adjustment schedule has been previously described [35]. The end points of treatment were disease progression, excessive toxicity, or achievement of resectability. Sites of initial disease progression were noted. In patients removed from the protocol for progression, systemic therapy was added or HAI therapy was changed; several patients received both HAI FUDR and systemic therapy, depending on the site of progression.

study design and statistics

The primary objective was to evaluate the antitumor activity of HAI FUDR in patients with unresectable PLC; assessment of treatment outcome and DCE-MRI variables were planned secondary objectives. The study followed a Simon two-stage design. At the first stage, 12 patients were enrolled; if there were less than one or one responder or if more than four patients had unacceptable toxicity, the study would be terminated and further studies of this regimen in this population would have been deemed unwarranted. If at least 2 of the first 12 patients responded, 22 more patients would be enrolled for a total of 34. If at least 6 of the 34 patients responded, the regimen would be recommended for further study. A true response rate of 30% or more would yield a 90% probability of recommending the regimen for further study. This probability reduces to 10% if the true response rate was 10%. Numerical data are presented as median values (range). Continuous and categorical variables were compared using Student's t-test or a chi-square test, respectively. Survival probabilities were computed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. In analyzing the DCE-MRI data for changes from baseline to the first post-treatment scans, variables were dichotomized around zero (i.e. positive or negative changes); for analyses of pretreatment data, variables were dichotomized around the median values.

results

patient demographics and baseline laboratory studies

From August 2003 through March 2007, 34 patients were enrolled. Complete treatment and follow-up information was available for all patients. Demographic and baseline laboratory data are shown in Table 1. ICC was the most common diagnosis (n = 26); 21 patients (61.8%) had multifocal intrahepatic disease while 11 (32.4%) had extensive portal venous involvement. The median tumor size was 9.7 cm (2.7–18.1 cm), with a median of 45% liver involvement. Four patients had chronic hepatitis (B or C) and five had cirrhosis or fibrosis. Seven patients (20.6%) had one or more prior therapies: ablation in five, systemic therapy in three, and resection in two.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, baseline laboratory studies, chemotherapy dosing, and treatment-related complications

| All patients (n = 34) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 12 (35.3%) |

| Female | 22 (64.7%) |

| Age (years) | 56.5 (30–85) |

| KPS | 80 (60–90) |

| Diagnosis | |

| ICC | 26 (76.5%) |

| HCC | 8 (23.5%) |

| Previous treatmenta | 7 (20.6%) |

| Ablationb | 5 |

| Systemic chemotherapy | 3 |

| Resection | 2 |

| % Liver involvement | 45% (30–80%) |

| Multifocal hepatic disease | 21 (61.8%) |

| Largest tumor diameter (cm) | 9.7 (2.7–18.1) |

| Chronic hepatitis (serology) | 4 (11.8%) |

| Cirrhosis/fibrosis (histology) | 5 (14.7%) |

| Pretreatment laboratory studies | |

| Alkaline phosphatase (μg/l) | 154.5 (76–1147) |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.3 (1.8–4.2) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.7 (0.3–2.4) |

| LDH (μg/l) | 167 (121–318) |

| AST | 42.5 (21–249) |

| ALT | 44 (13–343) |

| INR | 1.06 (0.85–1.53) |

| Platelets (103/ml) | 244 (102–806) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.0 (8.1–14.0) |

| Pretreatment serum tumor marker levels | |

| AFP (ng/ml) | 4.8 (1.1–80003) |

| CA19-9 (μg/l) | 44 (0–19700) |

| CEA (ng/ml) | 2.2 (0.5–52.7) |

Three patients were treated with more than one modality.

Hepatic artery embolization/chemoembolization or ethanol injection.

ICC, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AFP, α-fetoprotein; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

chemotherapy administration and treatment-related toxicity

All patients received HAI FUDR therapy according to the protocol. The median number of treatment cycles completed was 7 (2–25) (Table 2). Dose reductions, typically for serum liver enzyme elevations, were common [median = 1/patient (0–4)]; the median FUDR dose at the end of treatment was 62.5% lower (0%–98%) than the starting dose.

Table 2.

Chemotherapy dosing and treatment-related morbidity

| All patients (n = 34) | |

| Treatment cycles | |

| Total (per patient) | 7 (2–25) |

| Dose reduced (per patient) | 2.5 (0–24) |

| Dose reductions (per patient) | 1 (0–4) |

| Cycles held (per patient) | 1 (0–14) |

| Patients without dose reductions/cycles held | 6 (35.3%) |

| FUDR starting dose | 272 (168–376) |

| FUDR end dose | 99 (5–376) |

| % Dose reduction | 62.5 (0–98) |

| Treatment-related complications | |

| Chemotherapy related | 5 (14.7%) |

| Elevated serum bilirubin | 3 (2 grade 4, 1 grade 3) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (grade 3) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (grade 3) |

| Postoperative | 8 (23.5%) |

| Wound infection | 3 (2 grade 2, 1 grade 1) |

| Pump misperfusiona | 2 (1 grade 3, 1 grade 1) |

| Delerium | 1 (grade 1) |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 1 (grade 2) |

One patient required embolization of an aberrant vessel before starting treatment; a second patient developed an intrahepatic arterial–hepatic venous shunt 3 months after starting treatment and was removed from the study.

FUDR, Floxuridine.

Five patients (14.7%) experienced grade 3 or 4 toxicity (Table 2). Three patients had elevations of serum bilirubin (grade 4 in two and grade 3 in one), all of which resolved with dose modification; there were no biliary strictures. Two other grade 3 complications (migraine headache and diarrhea) were attributable to diuretic therapy and a preexisting condition, respectively. One patient was removed from the study after two cycles with disease progression and liver failure due to exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B infection. This problem, which ultimately resulted in death, may have resulted from the patient's decision to discontinue anti-hepatitis B virus medication; the remaining patients with chronic hepatitis experienced no such problems. Postoperative complications related to the pump placement occurred in eight patients (23.5%) (Table 2).

treatment response and disease progression

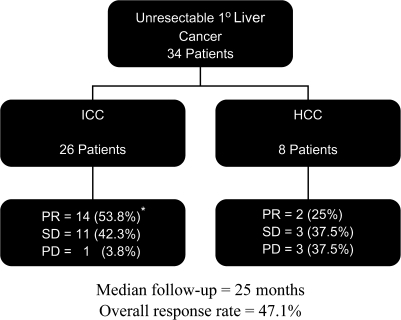

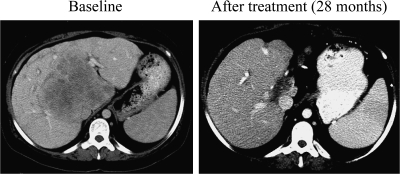

Sixteen patients had a partial response (PR) (47.1%), with response duration in the liver of 12.3 months (3.7–51.4 months); 14 patients had stable disease (SD) (41.2%) and three had progressive disease (PD) (8.8%). The disease control rate (complete response + PR + SD for at least two cycles) was 88.2%. Patients with ICC had a higher response rate (53.8%) compared with those with HCC (25%) (Figures 1 and 2). One patient with ICC responded sufficiently to undergo resection; the final histology of the resected specimen showed a complete necrosis.

Figure 1.

Outcome of all patients, stratified by diagnosis. * includes one patient who responded sufficiently to undergo resection and was found to have a complete pathologic response.

Figure 2.

Example of a patient with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma who responded to therapy. Panel at left shows the disease extent before treatment and the panel at right the residual disease after 28 months on therapy.

At a median follow-up of 25 months, 33 of 34 patients developed disease progression. In 21 patients (61.8%), the liver, either alone (n = 18) or in combination with an extrahepatic location (n = 3), was the site of initial progression; 12 patients (38.2%) progressed initially at an extrahepatic site only, 11 of whom eventually had hepatic disease progression. Of the 33 patients who progressed, 17 continued to receive HAI therapy, of whom 14 received HAI FUDR in conjunction with systemic cytotoxic therapy and three received an alternative HAI regimen; seven received systemic therapy followed by HAI and eight received systemic therapy alone [gemcitabine single agent (n = 11), gemcitabine/oxaliplatin, or irinotecan] Thus, 24 of 33 patients (72.7%) received additional HAI treatment after removal from the study.

survival

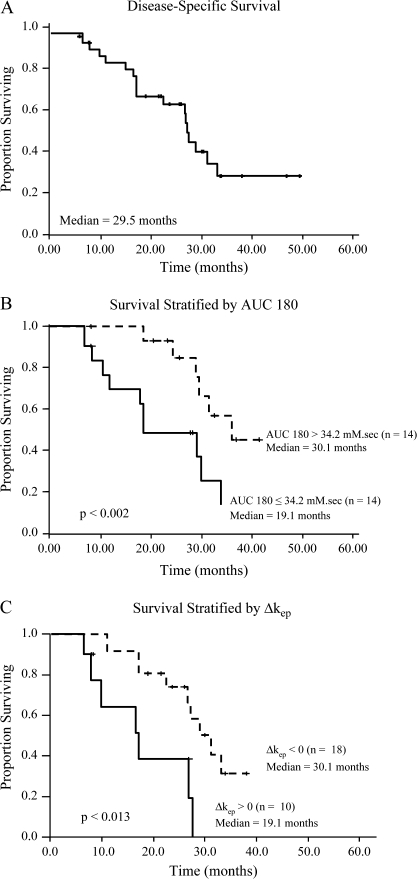

The median disease-specific survival was 29.5 months (Figure 3A) and was greater in those who responded (35.1 months) compared with those with SD (28.6 months) or PD (9.8 months) (P < 0.0021). The 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival rates were 88%, 67%, and 29%, respectively. Median progression-free survival (any site) was 7.4 months; hepatic progression-free survival (HPFS) was 10.3 months. HPFS was higher in patients with ICC compared with HCC (11.6 months versus 9.4 months, P < 0.043); no other disease-specific differences were noted.

Figure 3.

(A) Disease-specific survival for the entire cohort; (B) Disease-specific survival stratified by AUC 180; (C) disease-specific survival stratified by Δkep.

dynamic MRI

Complete DCE-MRI data were available for 28 patients. The time between baseline DCE-MRI and treatment start was 9.5 days (0–14 days); the time between baseline and first post-treatment DCE-MRI was 59 days (43–72 days).

Pretreatment AUC 90 and AUC 180 predicted survival (Table 3 and Figure 3B). Patients with an AUC 180 >34.2 mM·s on their baseline study (n = 14) had similar response rates (50% versus 35.7%, P < 0.44) but longer disease-specific survival (35.1 versus 19.1 months, P < 0.002) compared with patients with an AUC 180 ≤34.2 mM·s (n = 14); HPFS also tended to be greater in the group with AUC 180 >34.2 mM·s (11.5 versus 7.5 months, P < 0.18), although overall progression-free survival was similar. AUC 90 >17.1 mM·s was similarly associated with greater disease-specific survival (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline (pretreatment) integrated area under the concentration curve of gadolinium contrast at 90 (AUC 90) and 180 (AUC 180) s from the start of contrast enhancement

| AUC 90 > 17.1 (n = 14) | AUC 90 ≤ 17.1 (n = 14) | P | AUC 180 > 34.2 (n = 14) | AUC 180 ≤ 34.2 (n = 14) | P | |

| Response rate | 8 (57.1%) | 4 (28.6%) | 0.13 | 7 (50%) | 5 (35.7%) | 0.44 |

| Progression-free survival | 7.4 months | 6.8 months | 0.077 | 7.2 months | 7.3 months | 0.77 |

| Hepatic progression-free survival | 11.5 months | 7.5 months | 0.28 | 11.5 months | 7.5 months | 0.18 |

| Disease-specific survival | 35.1 months | 19.1 months | 0.019 | 35.1 months | 19.1 months | 0.002 |

| Survival >18 months | 12 (85.7.3%) | 9 (64.3%) | 0.19 | 13 (92.9%) | 8 (57.1%) | 0.029 |

| Survival >24 months | 10 (71.4%) | 5 (35.7%) | 0.058 | 10 (71.4%) | 5 (35.7%) | 0.058 |

Patients were stratified around the median values for both variables. Region of interest analyses were carried out. Units for AUC—mM·s.

AUC, area under the concentration curve.

Regarding changes from pretreatment to first post-treatment scans, Vx analyses of the top decile values for both Ktrans and kep revealed a survival correlation. Compared with baseline, a decrease in kep (i.e. a negative Δkep) on the first post-treatment DCE-MRI was associated with a disease-specific survival of 30.1 months and an 18-month survival of 88.9%, compared with 19.1 months (P = 0.013) and 60.0% (P = 0.023), respectively, when Δkep was positive (Table 4 and Figure 3C). Similarly, there was an inverse association between disease-specific survival and a decrease in ΔKtrans [33.1 months versus 28.6 months, P = 0.07 (Table 4)].

Table 4.

Changes in the volume transfer constant from the vascular space to the extracellular extravascular space (ΔKtrans) and the corresponding rate constant (Δkep) from baseline (pretreatment) to first post-treatment DCE-MRI scan as predictors of outcome

| ΔKtrans < 0a (n = 15) | ΔKtrans ≥ 0a (n = 13) | P | Δkep < 0a (n = 18) | Δkep > 0a (n = 10) | P | |

| Response rate | 8 (53.3%) | 4 (30.8%) | 0.23 | 9 (50.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | 0.31 |

| Progression-free survival | 7.4 months | 7.2 months | 0.31 | 7.3 months | 7.2 months | 0.11 |

| Hepatic progression-free survival | 7.5 months | 11.5 months | 0.66 | 11.5 months | 7.5 months | 0.15 |

| Disease-specific survival | 33.1 months | 28.6 months | 0.07 | 30.1 months | 19.1 months | 0.013 |

| Survival > 18 months | 13 (86.7%) | 8 (61.5%) | 0.13 | 16 (88.9%) | 5 (50.0%) | 0.023 |

| Survival > 24 months | 10 (66.7%) | 5 (38.5%) | 0.14 | 12 (66.7%) | 3 (30.0%) | 0.062 |

Patients were stratified into groups with positive or negative changes in Ktrans and kep voxel analysis of top decile values for each variable. Units for Ktrans and kep—1/min.

DCE-MRI, dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging.

discussion

With the rising incidence and mortality related to PLC, better therapies are desperately needed. Resection and transplantation (for HCC) are the most effective but are applicable to a small fraction of patients [3, 36]. Ablative therapies are similarly constrained by anatomical and disease-related factors and are less effective than surgery, and prolonged survival is rare [5]. Systemic chemotherapy has been equally disappointing. For ICC, the advent of irinotecan and gemcitabine has generally represented an advance [8], and contemporary agents, both cytotoxic and targeted, have likewise led to improved response rates for HCC. Despite improvements, however, survival in these series was ≤1 year. Recently, a randomized study evaluating sorafenib in patients with HCC showed a response rate of 2% and only a modest improvement in survival over placebo (10.7 versus 7.9 months) [12].

HAI chemotherapy offers several advantages over systemic and ablative therapy. First, using an agent with a favorable first-pass hepatic metabolic profile such as FUDR, very high doses can be administered directly into the hepatic arterial system with little or no systemic toxicity. Since tumors derive nearly all of their blood supply from the hepatic artery, high tumor drug levels can be achieved while maintaining hepatic perfusion via the portal venous system [13]. Unlike other local–regional therapies for PLC, HAI chemotherapy is not limited by tumor size, proximity to major vascular structures, or multifocality, all of which commonly preclude resection or ablation. The efficacy of HAI FUDR for hepatic colorectal metastases has been shown in both the adjuvant [14] and palliative settings (even after failure of systemic regimens). Experience with HAI therapy for PLC is more limited, generally confined to small series, although some benefit has been suggested [16, 17].

The current study shows that continuous HAI therapy with FUDR is active against PLC and is safe. Although dose modifications were common, primarily due to elevations in serum liver enzymes or serum bilirubin, these were mostly minor and resolved spontaneously, and no patient developed a biliary stricture. Response, TTP, and disease-specific survival were all greater than those observed in other trials and were achieved in the face of advanced intrahepatic disease (i.e. median of 45% liver replacement, tumor diameter ∼10 cm). Although no patient had distant disease initially, a large majority had gross multifocal disease, an indicator of intrahepatic metastases, and while survival of patients with liver-confined tumors may be slightly better than that of patients with extrahepatic metastases, the difference is likely small. In a recent review of 270 ICC patients seen at MSKCC, the survival of those with liver-confined disease treated with systemic chemotherapy was 10 months [3].

With the exception of one patient converted to resectability, all patients ultimately progressed, and nearly all were treated at some point with systemic therapy. While the impact of systemic treatment on outcome cannot be determined, it should be noted that the median survival of patients with PLC treated with cytotoxic systemic therapy alone is poor. It should also be emphasized that 55% of patients who progressed continued to have liver-confined disease and nearly three-fourths received additional HAI therapy after removal from the study, which is likely reflected in the long HPFS (11.6 months for ICC). Of note, over one-third of patients progressed initially at an extrahepatic site. Whether the concomitant use of systemic therapy would have impacted this result is unclear, but it underscores the risk of extrahepatic disease progression, even in the absence of clinical or radiographic evidence of such findings. Studies are now underway to evaluate the impact of adding systemic agents to regional FUDR/dex.

A major finding of the present study was the delineation of a potentially important role for DCE-MRI in predicting outcome, both before and early after treatment initiation. The baseline AUC 90 and AUC 180, measures of global tumor perfusion, directly correlated with better disease-specific survival. Of the variables measured, AUC is probably the easiest and the most reproducible; they require no kinetic modeling and are unaffected by variations related to data-fitting algorithms and parameter estimation [22, 37]. The AUC is a measure of the contrast agent delivered to and retained in the tumor over a period of time, and while perhaps not as specific physiologically as other variables, it correlates with higher tissue delivery of drug, which may have an impact on efficacy. By contrast, a change in kep and Ktrans on the initial post-treatment scan was inversely related to survival, suggesting that direct delivery of FUDR into the hepatic arterial system induces early and prognostically important changes in the tumor vasculature, in this case related to vascular endothelial permeability. Although not typically considered major mediators of tumor angiogenesis, cytotoxic agents are active in this regard [38]. Indeed, a recent report showed antiangiogenic activity of 5-fluorouracil-based drugs, mediated by up-regulation of thrombospondin-1 [39]. The possibility that HAI FUDR exerts some antitumor effects indirectly through changes in the tumor vasculature is therefore supported and provides a rational basis for the use of DCE-MRI to assess efficacy.

It is important to emphasize that, compared with other tumor types (i.e. colorectal cancer), the baseline vascularity of PLC is generally greater, and it is therefore not unreasonable to expect that changes in Ktrans and kep in response to therapy will also differ. The use of direct intra-arterial chemotherapy, compared with systemic therapy, may also be an important factor in this regard. Primary liver tumors often have necrotic regions, but it is the assessment of viable areas that is obviously of greatest interest for assessing therapeutic response. The top decile values of the kinetic maps, as used in the current study, appear to be the most sensitive to change. It should be stated that the cut-off values for AUC 90, AUC 180, ΔKtrans, and Δkep will require prospective validation in another dataset, and their importance in relation to other predictors of response will need to be determined.

The search for biomarkers that accurately predict response to treatment and outcome remains an area of intense research in clinical oncology. Such biomarkers, whether clinical, genetic, or radiologic, hold the promise of targeting therapy to patients most likely to benefit and sparing others toxicity from ineffective therapies. As a noninvasive imaging technique, DCE-MRI can be used to measure properties of tumor microvasculature [18]. As this and other studies have shown, DCE-MRI provides an in-depth, quantitative assessment of the tumor vasculature in vivo, allowing analysis of variables related to tumor perfusion and permeability. Such analyses have become increasingly important since changes in tumor size may underestimate treatment response [40]. The results of the present study underscore this point since none of AUC, ΔKtrans, and Δkep correlated significantly with response as measured by RECIST despite their association with survival. Indeed, these variables, particularly AUC and Δkep, were ultimately more potent predictors of disease-specific survival than tumor response, based on data collected before or soon after treatment initiation. The predictive value of DCE-MRI parameters for treatment response has been shown in other studies for different tumors; however, correlation of the MRI data with survival was not observed in these reports, the sole exception being the use of sorafenib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma [41].

In summary, this study shows that continuous HAI of FUDR/dex can be an effective and safe therapy for unresectable PLC. This study also suggests an important role for DCE-MRI as a potential biomarker of treatment outcome.

funding

Codman, Johnson and Johnson and the William H. Goodwin and Alice Goodwin Foundation and the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research and the Experimental Therapeutics Center at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center to LHS and National Cancer Institute (NCI R21 CA121553-01A1) to WRJ.

Acknowledgments

Presented in part at the 43rd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, 1–5 June 2008.

References

- 1.El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:745–750. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903113401001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:1353–1357. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Endo I, Gonen M, Yopp AC, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: rising frequency, improved survival, and determinants of outcome after resection. Ann Surg. 2008;248(1):1–13. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318176c4d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong Y, Sun RL, Jarnagin W, et al. An analysis of 412 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma at a Western center. Ann Surg. 1999;229:790–799. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199906000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng BQ, Jia CQ, Liu CT, et al. Chemoembolization combined with radiofrequency ablation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 3 cm: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1669–1677. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.14.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood TF, Rose DM, Chung M, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of 231 unresectable hepatic tumors: indications, limitations, and complications. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:593–600. doi: 10.1007/BF02725339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knox JJ, Hedley D, Oza A, et al. Combining gemcitabine and capecitabine in patients with advanced biliary cancer: a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2332–2338. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.51.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philip PA, Mahoney MR, Allmer C, et al. Phase II study of erlotinib in patients with advanced biliary cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3069–3074. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andre T, Tournigand C, Rosmorduc O, et al. Gemcitabine combined with oxaliplatin (GEMOX) in advanced biliary tract adenocarcinoma: a GERCOR study. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1339–1343. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abou-Alfa GK, Schwartz L, Ricci S, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4293–4300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llovet JM. Sorafenib improved survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): results of a phase III randomized placebo-controlled trial (SHARP trial) J Clin Oncol 2007 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. 2007;25(Suppl):18S. LBA1 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ensminger WD, Rosowsky A, Raso V, et al. A clinical-pharmacological evaluation of hepatic arterial infusions of 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine and 5-fluorouracil. Cancer Res. 1978;38:3784–3792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kemeny N, Huang Y, Cohen AM, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of chemotherapy after resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:2039–2048. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemeny N, Jarnagin W, Paty P, et al. Phase I trial of systemic oxaliplatin combination chemotherapy with hepatic arterial infusion in patients with unresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4888–4896. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atiq OT, Kemeny N, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Treatment of unresectable primary liver cancer with intrahepatic fluorodeoxyuridine and mitomycin C through an implantable pump. Cancer. 1992;69:920–924. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920215)69:4<920::aid-cncr2820690414>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clavien PA, Selzner N, Morse M, et al. Downstaging of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver metastases from colorectal cancer by selective intra-arterial chemotherapy. Surgery. 2002;131:433–442. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.122374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hylton N. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging as an imaging biomarker. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3293–3298. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devries AF, Griebel J, Kremser C, et al. Tumor microcirculation evaluated by dynamic magnetic resonance imaging predicts therapy outcome for primary rectal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2513–2516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoskin PJ, Saunders MI, Goodchild K, et al. Dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance scanning as a predictor of response to accelerated radiotherapy for advanced head and neck cancer. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:1093–1098. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.863.10700827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evelhoch J, Garwood M, Vigneron D, et al. Expanding the use of magnetic resonance in the assessment of tumor response to therapy: workshop report. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7041–7044. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evelhoch JL, LoRusso PM, He Z, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging measurements of the response of murine and human tumors to the vascular-targeting agent ZD6126. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3650–3657. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan B, Thomas AL, Drevs J, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging as a biomarker for the pharmacological response of PTK787/ZK 222584, an inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases, in patients with advanced colorectal cancer and liver metastases: results from two phase I studies. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3955–3964. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Laarhoven HW, Klomp DW, Rijpkema M, et al. Prediction of chemotherapeutic response of colorectal liver metastases with dynamic gadolinium-DTPA-enhanced MRI and localized 19F MRS pharmacokinetic studies of 5-fluorouracil. NMR Biomed. 2007;20:128–140. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen PJ, Nissan A, Picon AI, et al. Technical complications and durability of hepatic artery infusion pumps for unresectable colorectal liver metastases: an institutional experience of 544 consecutive cases. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kety SS. The theory and applications of the exchange of inert gas at the lungs and tissues. Pharmacol Rev. 1951;3:1–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinmann H, Laniado M, Mützel W. Pharmacokinetics of GdDTPA/dimeglumine after intravenous injection into healthy volunteers. Physiol Chem Phys Med NMR. 1984;16:167–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tofts PS, Kermode AG. Measurement of the blood-brain barrier permeability and leakage space using dynamic MR imaging. 1. Fundamental concepts. Magn Reson Med. 1991;17:357–367. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910170208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Huang W, Panicek DM, et al. Feasibility of using limited-population-based arterial input function for pharmacokinetic modeling of osteosarcoma dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI data. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:1183–1189. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tofts PS, Brix G, Buckley DL, et al. Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T(1)-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: standardized quantities and symbols. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;10:223–232. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199909)10:3<223::aid-jmri2>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayes C, Padhani AR, Leach MO. Assessing changes in tumour vascular function using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:154–163. doi: 10.1002/nbm.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson A, O'Connor JP, Parker GJ, et al. Imaging tumor vascular heterogeneity and angiogenesis using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3449–3459. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mills SJ, Patankar TA, Haroon HA, et al. Do cerebral blood volume and contrast transfer coefficient predict prognosis in human glioma? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:853–858. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kemeny N, Cohen A, Seiter K, et al. Randomized trial of hepatic arterial floxuridine, mitomycin, and carmustine versus floxuridine alone in previously treated patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:330–335. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikai I, Arii S, Okazaki M, et al. Report of the 17th Nationwide Follow-up Survey of Primary Liver Cancer in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:676–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galbraith SM, Lodge MA, Taylor NJ, et al. Reproducibility of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in human muscle and tumours: comparison of quantitative and semi-quantitative analysis. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:132–142. doi: 10.1002/nbm.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basaki Y, Chikahisa L, Aoyagi K, et al. Gamma-hydroxybutyric acid and 5-fluorouracil, metabolites of UFT, inhibit the angiogenesis induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. Angiogenesis. 2001;4:163–173. doi: 10.1023/a:1014059528046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ooyama A, Oka T, Zhao HY, et al. Anti-angiogenic effect of 5-fluorouracil-based drugs against human colon cancer xenografts. Cancer Lett. 2008;267(1):26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michaelis LC, Ratain MJ. Measuring response in a post-RECIST world: from black and white to shades of grey. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:409–414. doi: 10.1038/nrc1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Dwyer P, Rosen M. Pharmacodynamic study of BAY 43-9006 in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2005 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings. 2005;23(Suppl):16S. Part I of II 3005. 2005. [Google Scholar]