Abstract

Cancer stem cells are a limited population of tumor cells that are thought to reconstitute whole tumors. The Hoechst dye exclusion assay revealed that tumors are composed of both a main population and a side population of cells, which are rich in cancer stem cells. NR0B1 is an orphan nuclear receptor that is expressed to a greater extent in the side population, as compared with the main population, of a lung adenocarcinoma cell line. In this study, we investigated the role of NR0B1 in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Reduction of NR0B1expression levels in lung adenocarcinoma cell lines resulted in vulnerability to anti-cancer drugs and decreased abilities for invasion, in vitro colony formation, and tumorigenicity in non-obese diabetic/severe compromised immunodeficient mice. When 193 cases of lung adenocarcinoma were immunohistochemically examined, higher levels of NR0B1 expression correlated with higher rates of lymph node metastasis and recurrence. Multivariate analysis revealed high NR0B1 expression levels, stage of the disease, and size of tumor to be independent unfavorable prognostic factors for overall and disease-free survival rates. In clinical samples, NR0B1 expression levels inversely correlated to the proportion of methylated CpG sequences around the transcription initiation site of the NR0B1 gene, suggesting the epigenetic control of NR0B1 transcription in lung adenocarcinoma. In conclusion, NR0B1 might play a role in the malignant potential of lung adenocarcinoma.

Cancer cells comprise heterogeneous groups of cells; only a small population of cancer cells possesses the ability to reconstitute whole tumor.1,2,3 This population, called cancer stem cells (CSCs), efficiently forms colonies in semisolid culture and is xenotransplantable in non-obese diabetic/severely compromised immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice.4 CSCs were first identified in leukemia,5,6 and subsequently isolated from the solid tumors, such as breast, brain, prostate, colon, pancreatic, and head/neck cancers.7,8,9,10,11,12,13 CSCs highly express various chemical transporters and could efficiently efflux several chemicals, which might render to resistance to anti-cancer drugs and tumor recurrence.4,14,15

Efficient dye-efflux ability could be used for the isolation of CSCs. Most cancer cells are stained intensely with the fluorescent dye Hoechst 33342, whereas cancer cells with stem cell properties are not.4,14,15 At flow-cytometry analysis, cells with a low level of Hoechst 33342 are visualized as a faintly stained population, which is called the side-population (SP).16 Only the SP gives rise to both SP and non-SP (the main population, hereafter called MP), and the SP, but not MP, is tumorigenic in NOD/SCID mice.17 These findings support the notion that CSCs are enriched in the SP. Recently, the presence of SP was reported in cancer cell lines established from various tumors, such as glioma, mammary carcinoma, and lung cancer.18,19,20 Proteins highly expressed in the SP may become the candidate of CSC markers.

Lung cancer has become the most common cause of cancer death worldwide since 1985, and the annual mortality was 1.18 million peoples in the world.21 Despite the advances in the methods for detection and treatment of lung cancer, its prognosis still remains unfavorable. Remnant tumor cells resistant to anti-cancer drugs may provide a basis for recurrence after chemotherapy. In this context, evaluation of lung cancers from the standpoint of CSCs may be important. To date, however, any markers useful for detection of CSCs in lung cancer have not been known. Recently, Seo et al22 reported that several genes were highly expressed in SP of lung adenocarcinoma cell lines: one of them was the gene for NR0B1, a recently characterized member of the orphan nuclear receptor family.23 NR0B1 (also called dosage-sensitive sex reversal/adrenal hypoplasia congenital critical region on the X chromosome 1; DAX1) acts as a negative regulator of steroid production, and is expressed in the reproductive and endocrine systems.23 A recent study on the embryonic stem cells showed that NR0B1 is abundantly expressed in an undifferentiated status, but its expression level is down-regulated on differentiation.24 Knocked down of NR0B1 expression resulted in differentiation of embryonic stem cells, suggesting a role of NR0B1 for the maintenance of undifferentiated state.25

NR0B1 is expressed in several kinds of cancers, such as endometrial carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma, prostatic carcinoma, and Ewing’s sarcoma.26,27,28,29,30 Recently, Mendiola et al29 and Kinsey et al30 reported that NR0B1 was a target of EWS/FLI fusion protein in Ewing’s sarcoma: knocked-down expression of NR0B1 in the Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines resulted in the defect of colony formation ability and tumorigenicity. These findings suggested that NR0B1 expression could be a marker for tumorigenic cells in lung adenocarcinoma, as well as Ewing’s sarcoma. To date, there have not been any reports describing the expression and role of NR0B1 in lung adenocarcinoma. In the present study, the role of NR0B1 was investigated in lung adenocarcinoma cell line, and subsequently, the clinicopathological features between lung adenocarcinoma with high and low expression level of NR0B1 were compared. In addition, the epigenetic regulation mechanism of NR0B1 gene transcription was investigated.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Flow Cytometry

The human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines A549 and PC-14 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) and the Riken Bioresource Center (Tsukuba, Japan), respectively. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Sigma, St Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Nippon Bio-supp. Center, Tokyo, Japan; DMEM-10% FCS). SP analysis was performed according to the protocol of Goodell’s laboratory with minor modifications.16 Briefly, cells (1 × 106/ml) were incubated at 37°C for 90 minutes with 5 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Sigma) with or without 50 μmol/L verapamil (Sigma), collected and resuspended in ice-cold PBS with 2% FCS and 2 μg/ml propidium iodide (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). SP and MP cells were analyzed and sorted with fluorescence-activated cell sorting-Vantage (Becton Dickinson, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) carrying a triple-laser. The Hoechst 33342 was excited with the UV laser at 350 nm, and fluorescence emission was measured with 424/BP44 (Hoechst blue) and 660/BP20 (Hoechst red) optical filters.

Quantification of mRNA Levels by Real-Time Reverse-Transcription PCR

RNA was extracted using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with DNase I treatment. Total RNA was subjected to reverse transcription (RT) by Superscript III (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the single strand cDNA was obtained. The mRNA levels for NR0B1, B cell/chronic lymphocytic leukemia lymphoma (Bcl)-2, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) genes were verified using TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as recommended by the manufacturer. The amount of NR0B1, Bcl-2, and MMP-2 mRNA was normalized to that of GAPDH mRNA, and the normalized value was shown as relative mRNA amount.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR Analysis

The reverse-transcribed product (1 or 0.1 μl) was added to 25 μl of a PCR mixture containing 1.25 U of TaqDNA polymerase (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and 25 pmol of each primer. The sequences of the primers were: 5′-CGACTTCGCCGAGATGTCCAGCCAG-3′ and 5′-ACTTGTGGCCCAGATAGGCACCCAG-3′ for Bcl-2, 5′-GGACCCGGTGCCTCAGGA-3′ and 5′-CAAAGATGGTCACGGTCTGC-3′ for BclII-associated x (Bax), 5′-TTGGACAATGGACTGGTTGA-3′ and 5′-GTAGAGTGGATGGTCAGTG-3′ for Bcl-XL/S,5′-AGATCTTCTTCTTCAAGGACCGGTT-3′ and 5′-GGCTGGTCAGTGGCTTGGGGTA-3′ for MMP-2, 5′-TTGCGGCCATCTACAGGAG-3′ and 5′-ACTGGGGATCGTTATACATC-3′ for urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), 5′-TGCATGCAGTGTAAGACC-3′ and 5′-CTGCGGCAGATTTTCAAG-3′ for uPA receptor, 5′-ATCCTGTTGTTGCTGTGGCTGATAG-3′ and 5′-TGCTGGGTGGTAACTCTTTATTTCA-3′ for tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1, 5′-TTTATCTACACGGCCCCCTCCTCAG-3′ and 5′-ACGGGTCCTCGATGTCAAGAAACTC-3′ for TIMP-2, and 5′-GTCCACTGGCGTGTTCACCA-3′ and 5′-GTGGCAGTGATGGCATGGAC-3′ for GAPDH.

Knocked Down of NR0B1 Expression by Small Interfering RNA

To generate a stably expressing small interfering (si)-RNA system, the BLOCK-iT Pol II miR RNAi expression vector kit (Invitrogen) was used. Cells stably expressing the NR0B1 si-RNA and control cells stably expressing vector alone were established in DMEM-10% FCS containing blasticidin S (Invivogen) at a concentration of 10 μg/ml in A549 and 12 μg/ml in PC-14.

Immunoblotting

Cells were harvested, and the whole cell lysates were prepared as described previously.31 The lysates were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to Immobilon (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and incubated with anti-NR0B1 (Abcam Ltd, Cambridge, UK) or anti-actin (Sigma) antibodies. After washing, the blots were incubated with an appropriate peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (MBL, Nagoya, Japan), and then reacted with Renaissance reagents (NEN, Boston, MA) before exposure.

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell growth of A549 was shown by number of cells. Approximately 1 × 104 cells were seeded onto cell culture plates with DMEM-10% FCS. The growth medium was changed every 2 days and cell numbers were counted.

Assessment of Anti-Cancer Drug Topotecan Effect

Topotecan acts as a topoisomerase I inhibitor, and induces apoptosis in tumor cells.32 The effect of topotecan was evaluated as described by Tomicic et al33 with minor modification. Briefly, cells (1 × 104) were seeded onto cell culture plates with DMEM-10% FCS, cultured for 12 hours, and then various concentration of topotecan (LKT Laboratories Inc, St Paul, MN) was added. After 12 hours, the viability of cells was assessed with Premix WST-1 cell assay system (Takara Bio Inc, Kyoto, Japan). The absorbance at 450 nm was divided by that obtained in the cells without topotecan, and the resultant value was shown as viability index.

Matrigel Invasion Assay

Invasion of tumor cells into the Matrigel was examined with BD BioCoat Matrigel Invasion Chamber (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Briefly, cells were seeded in DMEM without FCS on the Matrigel invasion chamber, and cultured in DMEM-10% FCS for 30 hours. Invading cells were stained with Diff-quick staining kit (Siemens, Munich, Germany). Number of invading cells was counted at five microscopic fields per well at a magnification of ×100, and the extent of invasion was expressed as the average number of cells per mm2.

In Vitro Colony Formation Assay

Cells were suspended in a volume of 0.1 ml of DMEM-10% FCS, and 500 cells were plated in culture dishes with 1 ml of methylcellulose-containing DMEM supplemented with 15% FCS. The number of colonies was counted on day14.

Mice and Xenograft Transplantation

Six-to 8-week-old female NOD/SCID mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories Japan (Kanagawa, Japan) and kept under specific pathogen-free conditions. Before xenotransplantation, the mice were deeply anesthetized. All animal experiments were performed according to the guideline of Osaka University Animal Center, and approved by the institutional review board of committee of animal experiments (No. 753). For xenograft transplantation, cells (1 × 104) were suspended in 0.2 ml of Matrigel (BD Biosciences), and were injected subcutaneously into NOD/SCID mice. The tumor volume was estimated using the following formula: (width)2 × (length)/2 according to the report by Meyer-Siegler et al.34

In Vitro Methylation

The luciferase construct that contained promoter region of NR0B1 starting from nt −47435 was incubated with SssI methylase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) in the presence (methylated) or absence (mock) of S-adenosylmethionine, as recommended by the manufacturer. After DNA isolation, 1 μg of the methylated or mock luciferase construct was transiently transfected into A549, together with 0.2 μg of the phRL-TK containing Renilla luciferase gene (Promega, Madison, WI) using Transfast transfection reagent (Promega). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the luciferase activity was measured by Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Promega).

Bisulfite Modification and DNA Sequencing Analysis

One μg of genomic DNA was modified with sodium bisulfite using EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen), and used for PCR as a template. The PCR reaction mixture contained 1 μl of DNA in a total volume of 25 μl, 2.5 μl of 10× PCR buffer II, 5 μmol/L MgCl2, 250 μmol/L deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1 μmol/L of each primer, and 1.25units Taq gold. The PCR buffer II, MgCl2, and Taq gold are parts of the AmpliTaq Gold with Gene Amp kit (Applied Biosystems). Sequence of the primers was as follows; 5′-AGGAAAGTGTTTAGGAGTTTTT and 5′-CCTAAAACCTATTTATACCT. The PCR was done at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 1 minute, 51°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute. In this condition, equal number of clones was obtained for samples with methylated and unmethylated NR0B1 promoter when equal amount of clone was mixed. Amplified PCR fragments were purified with QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen), and was subcloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). The sequences of the amplified fragments were analyzed using an ABI 3100 sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Patients

A total of 193 patients who underwent surgery for lung adenocarcinoma at Osaka University Hospital during the period from January 1993 to January 2004 were examined. The histological stage was determined according to the sixth edition of the Union International Contre le Cancer—TNM staging system.36 Histological specimens were fixed in 10% formalin and routinely processed for paraffin embedding. Paraffin-embedded specimens were stored in the dark room in the Department of Pathology of Osaka University Hospital at room temperature, and were sectioned at 4 μm thickness at the time of staining. All patients were followed up with laboratory examinations including routine peripheral blood cell counts at 1- to 6-month intervals, chest roentgenogram, computed tomographic scan of the chest, and endoscopic examinations of the bronchus at 6- to 12-month intervals. The follow-up period for survivors ranged from 5 to 150 (median, 61) months. The mRNA and genomic DNA were obtained from several tumor samples, and stocked in −80°C. The study was approved by the ethical review board of Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University (No. 737).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunoperoxidase procedure was performed on the paraffin-embedded sections with standard avidin- biotin-peroxidase complex method. After antigen retrieval with Pascal pressurized heating chamber (DAKO A/S, Glostrup, Denmark), the sections were incubated with anti-NR0B1 (Abcam; 1:100). As the negative control, staining was performed in the absence of primary antibody. Immunohistochemically stained sections were evaluated independently by two investigators (T. O. and E. M.): the results were compared and discussed for patients with discrepant findings.

Statistics

Statistical analysis for experimental studies was performed using Student’s t-tests. The values are shown as the mean ± SE of at least three experiments. Statistical analysis for clinical samples was performed using StatView software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Five-year overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the differences in survival curves were analyzed by the log-lank test. Independent prognostic factors were analyzed by the Cox’s proportional hazards regression model.

Results

High Expression Level of NR0B1 in SP of A549 Cells and Effects of its Knocked-Down by si-RNA

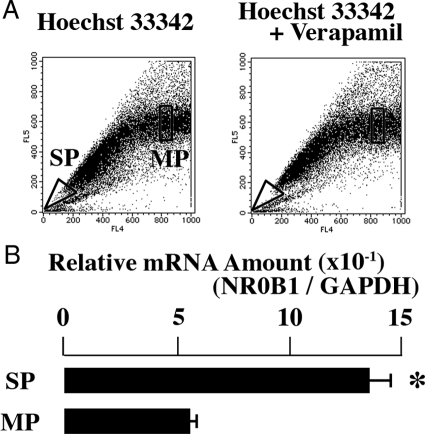

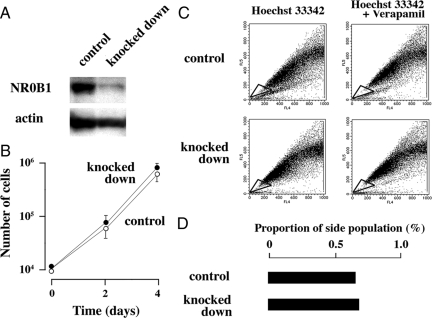

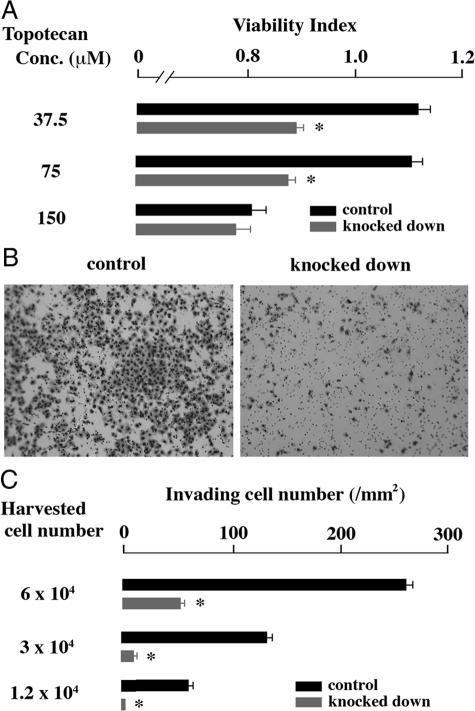

To examine whether expression level of NR0B1 was higher in SP than in MP, A549 cells were stained with Hoechst33342, and the SP and MP were independently sorted (Figure 1A). The expression level of NR0B1 was approximately three times higher in the SP than in the MP (Figure 1B). The expression level of NR0B1 was reduced by si-RNA, but did not significantly affect the proliferative activity and the proportion of SP among A549 cells (Figure 2, A–D). Whereas, the anti-cancer effect of topotecan, which is a topoisomerase I inhibitor and induces apoptosis in tumor cells, was stronger in knocked down cells than in control cells at the concentration of 37.5 and 75 μmol/L (Figure 3A). In Matrigel invasion assay, the number of invading cells in knocked-down cells was lower than that of the control cells, indicating that the knocked-down expression of NR0B1 resulted in a defect of invasive ability (Figure 3, B and C).

Figure 1.

High NR0B1 expression in SP of A549. A: Dot blot analysis of A549 cells stained with Hoechst 33342 dye in the absence (left) or presence (right) of verapamil. SP and MP cells were boxed. B: Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed with mRNA obtained from SP and MP of A549. The amount of NR0B1 mRNA was normalized for the amount of GAPDH mRNA. The values represent the mean ± SE of three experiments. *P < 0.01 by the Student’s t-test.

Figure 2.

Effect of NR0B1 expression on the proliferative activity and the SP formation. A: Immunoblot analysis for the amount of NR0B1 protein in the control and si-RNA knocked down cells. B: Comparison of cell proliferation of NR0B1 knocked down cells to that of control cells. The values represent the mean ± SE of three experiments. C: Dot blot analysis of control (upper) and knocked down (lower) cells stained with Hoechst 33342 dye in the absence (left) or presence (right) of verapamil. SP cells were boxed. D: Proportion of SP in the control and knocked down cells.

Figure 3.

Effect of NR0B1 expression on the resistance against topotecan and the cell invasion activity. A: Viability in the presence of various amount of topotecan was compared. B: Matrigel invasion assay. Cells invading through Matrigel are shown. Original magnification, ×100. C: Invading cell number per mm2. The values shown in (A) and (C) are the mean ± SE of three experiments. *P < 0.01 by the Student’s t-test.

Effect of NR0B1 on Colony Formation and Tumorigenic Abilities

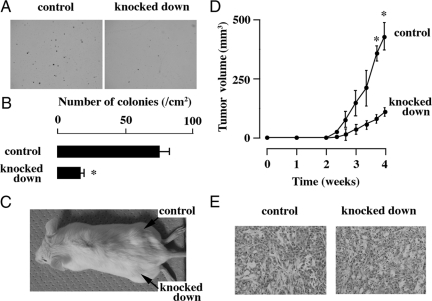

The in vitro colony formation and in vivo tumorigenic activities of NR0B1 knocked-down cells were evaluated. As compared with the control cells, NR0B1 knocked-down cells formed lower number of colonies in vitro (Figure 4, A and B). When 1 × 104 cells were injected into NOD/SCID mice, the size of tumors derived from NR0B1 knocked-down cells was significantly smaller than that of control cells (Figure 4, C and D). The tumor derived from either control or knocked-down cells histologically showed glandular structures, mimicking lung adenocarcinoma (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Effect of NR0B1 on the in vitro colony formation and the in vivo tumorigenicity activities. A: Colonies derived from the control and the NR0B1 knocked down cells. Original magnification, ×40. B: Number of colonies per cm2. C: Tumors in NOD/SCID mice at the injection sites of the control and the knocked down cells. D: The change of the volume of tumors. E: Histology of tumors derived from the control and the knocked down cells. Original magnification, ×400. The values in (B) and (D) represent the mean ± SE of three experiments. *P < 0.01 by the Student’s t-test.

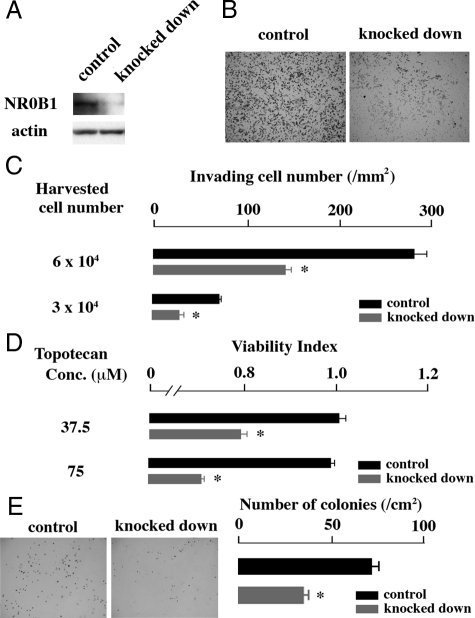

Effect of NR0B1 in Another Lung Cancer Cell Line

To examine the effect of NR0B1 observed in A549 was applicable to another lung adenocarcinoma cell line, the NR0B1 expression was knocked down in PC-14 (Figure 5A). Matrigel invasion assay revealed that the number of invading cells at NR0B1-knocked down condition reduced to half of the control cells (Figure 5, B and C). The anti-cancer effect of topotecan was stronger in knocked down cells than in control cells (Figure 5D). In addition, the in vitro-formed colony number derived from knocked down cells was smaller than that of control cells (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Effect of NR0B1 in PC-14. A: Immunoblot analysis for the amount of NR0B1 protein in the control and si-RNA knocked down PC-14 cells. B: Matrigel invasion assay using PC-14 cells. Cells invading through Matrigel were shown. Original magnification, ×100. C: Invading cell number per mm2. D: Viability of PC-14 cells in the presence of topotecan was compared. E: Colonies derived from the control and the NR0B1 knocked down PC-14 cells, and the number of colonies per cm2. The values in (C), (D), and (E) represent the mean ± SE of three experiments. *P < 0.01 by the Student’s t-test.

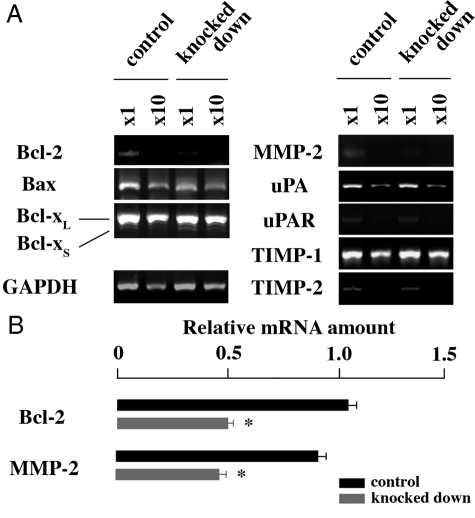

Decreased Expression Level of Apoptosis- and Invasion-Related Genes in NR0B1 Knocked-Down Cells

To examine why the colony formation and invasion abilities were defective in NR0B1-knocked down cells, the expression level of apoptosis- and invasion-related genes (Bcl-2, Bax, Bcl-XL/S, MMP-2, uPA, uPA receptor, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2) was analyzed. Among the examined genes, Bcl-2 and MMP-2 expression levels were lower in knocked-down cells than in control cells (Figure 6A). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR revealed that the amount of Bcl-2 and MMP-2 mRNAs in knocked down cells decreased to half of control cells (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Expression of apoptosis- and invasion-related genes in NR0B1-knocked down A549 cells. A: Semiquantitative RT-PCR. B: Real-time quantitative RT-PCR to examine the expression level of Bcl-2 and MMP-2. The value is shown as the mean ± SE. *P < 0.01 by the Student’s t-test.

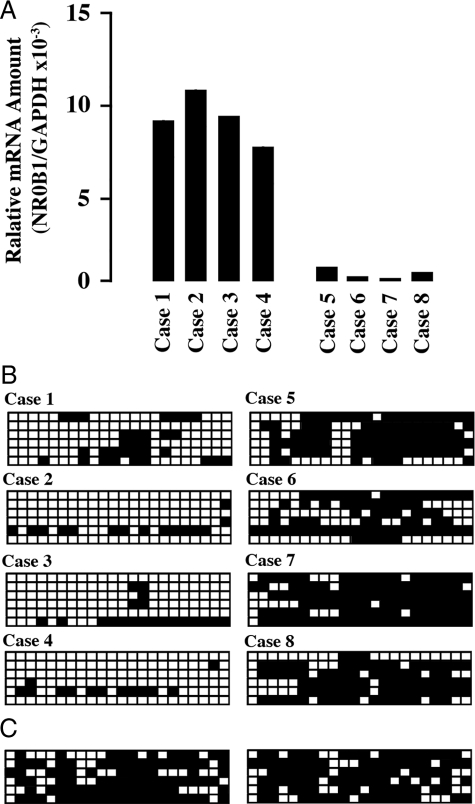

Epigenetic Regulation of NR0B1 Expression

A number of CpG sequences were found around the transcription initiation site of NR0B1 gene (Figure 7A), suggesting that the transcription of NR0B1 gene might be epigenetically regulated. To examine this, the luciferase construct containing NR0B1 promoter was methylated in vitro using SssI methylase, and the methylated or mock-methylated promoter construct was transiently transfected into A549. The methylated promoter construct, but not the mock-methylated construct, was resistant to digestion with methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme HpaII (Figure 7B), which confirmed that the CpG sequences of methylated construct had been completely methylated in vitro. When transfected into A549, higher luciferase activities were detected for the mock-methylated NR0B1 promoter than for the methylated NR0B1 promoter (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Effect of methylation on NR0B1 promoter activity. A: CpG sequences in the NR0B1 promoter. The vertical line represents a single CpG site. Transcription initiation site (TIS) is shown as arrow. B: Digestion patterns with the methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme HpaII of methylated and mock-methylated reporter plasmids. The luciferase reporter plasmid containing NR0B1 promoter was methylated or mock-methylated in vitro. Subsequently, each construct was digested with HpaII and electrophoresed. C: Relative luciferase activities of the methylated and mock-methylated NR0B1 constructs. The values represent the mean ± SE of three experiments. *P < 0.01 by the Student’s t-test. The SE of the methylated construct was too small to be shown.

Next, the correlation of methylated CpG proportion with NR0B1 expression level was analyzed in clinical samples of lung adenocarcinoma. The NR0B1 expression level in clinical samples was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. The genome DNA was extracted from each four case of lung adenocarcinoma showing high (Figure 8A, case 1 to case 4) and low level of NR0B1 expression (Figure 8A, case 5 to case 8). Bisulfite sequencing revealed that the proportion of methylated CpG sites was lower in cases with high NR0B1 expression than in cases with low NR0B1 expression (Figure 8B). The proportion of methylated CpG sites was high in the normal lung tissue (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Inverse correlation of NR0B1 expression level to the proportion of methylated CpG sequences in clinical samples of lung adenocarcinoma. A: Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed with mRNA obtained from tumors. The amount of NR0B1 mRNA was normalized for the amount of GAPDH mRNA. The highest four and the lowest four cases were shown (cases 1 to 4, and cases 5 to 8, respectively). B: Methylation status of CpG sequences in NR0B1 promoter. Six clones for each population were analyzed by bisulfite sequencing. Open and closed squares denote unmethylated and methylated cytosines, respectively. C: Methylation status of CpG sequences in NR0B1 promoter of normal lung tissue from two cases.

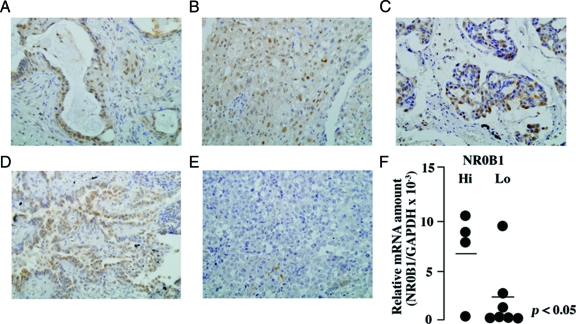

Immunohistochemical Analysis of NR0B1 Expression in Lung Adenocarcinoma

Correlation of NR0B1 expression with clinicopathological findings was examined in clinical samples of lung adenocarcinoma. At immunohistochemistry, signals for NR0B1 were detected in cancerous lesions but not in the non-cancerous lesions. The subcellular localization of NR0B1 signals was detected mainly in the nuclei of adenocarcinoma cells in some cases (Figures 9, A–C), but detected not only in the nucleus but also in the cytoplasm in others (Figure 9D); nuclear staining pattern in 27 cases, cytoplasmic pattern in 25 cases, and nucleocytoplasmic pattern in 53 cases. Few signals could be detected in several cases (Figure 9E). According to the method by Saito et al,26 a total of more than 500 tumor cells from three different representative fields were examined, and the proportion of cells with NR0B1 signals was counted. The previous reports on NR0B1 expression in endometrial adenocarcinoma26 and prostatic carcinoma28 used a cut-off point of 10%. Therefore, in this study, we used the same cut-off point; the cases with more than 10% positive cells and fewer than 10% positive cells were defined as NR0B1-hi and NR0B1-lo, respectively.

Figure 9.

NR0B1 expression in clinical samples of lung adenocarcinoma. A–E: Representative pictures of NR0B1 immunostaining in various cases. (×400) NR0B1 signals were detected in the nuclei of approximately 90% (A), 70% (B), 30% (C) of tumor cells. In some cases, the signals were detected not only in the nucleus but also in the cytoplasm (D). In other cases, few NR0B1-positive tumor cells were detected (E, <1%). F: Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed with mRNA obtained from 11 tumors as described in Figure 8A. The amount of NR0B1 mRNA was normalized for the amount of GAPDH mRNA. The amount of NR0B1 mRNA was higher in immunohistochemically defined NR0B1-hi cases than in NR0B1-lo cases. The bar shows mean value of NR0B1 amount.

To confirm the specificity of immunohistochemical staining for NR0B1 expression, quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed on 11 cases with lung adenocarcinoma from which mRNA could be obtained (4 NR0B1-hi and 7 NR0B1-lo cases at immunohistochemical results). The amount of NR0B1 mRNA was significantly higher in cases with NR0B1-hi expression at immunohistochemistry than those with NR0B1-lo expression (P < 0.05, Figure 9F). These results showed that the immunohistochemical evaluation is a reliable method for evaluation of NR0B1 expression.

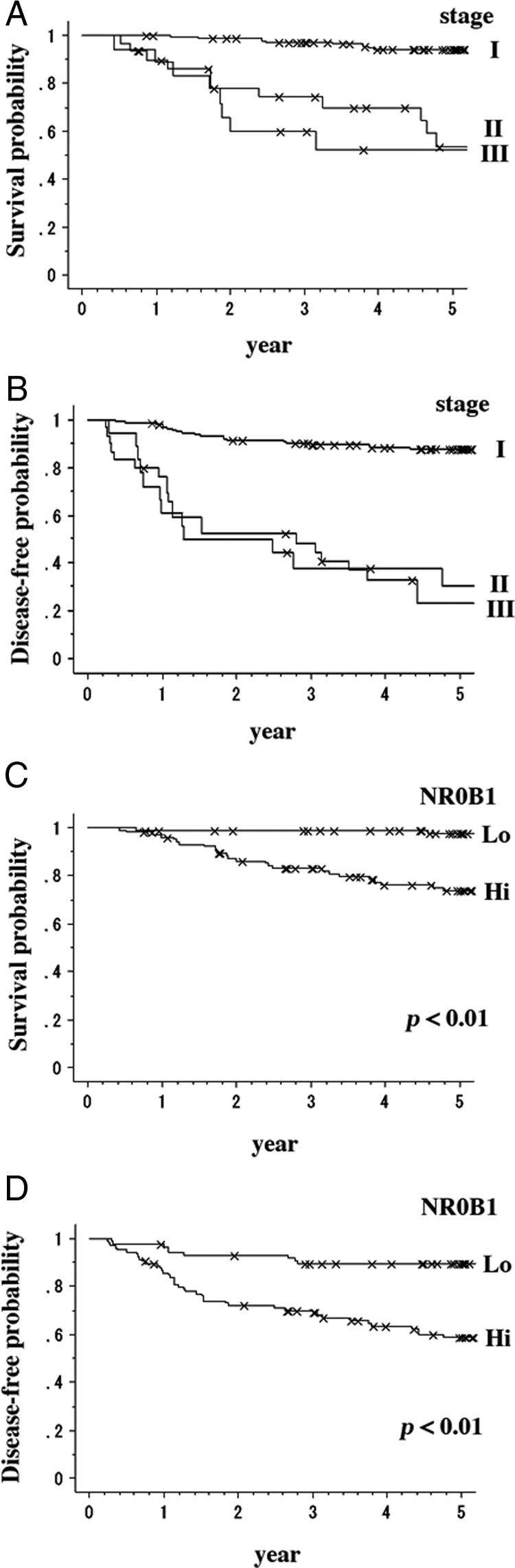

Brief clinical findings of 193 cases are summarized in Table 1. There were 107 males and 86 females with ages ranging from 33 to 82 (median, 64) years. Size of the main tumor ranged from 8 to 80 (median, 20) mm. Stage of tumor was I in 145 patients, II in 18, and III in 30. Tumor recurrence was found in 53 cases with intervals from surgery ranging from 2.9 to 145.3 (median 15.2) months. Five year OS in all patients, patients with stage I, II, and III was 84.8%, 95.1%, 52.4%, and 53.8%, respectively (Figure 10A). DFS in all patients, patients with stage I, II, and III was 73.1%, 87.9%, 30.5%, and 23.4%, respectively (Figure 10B).

Table 1.

Brief Summary of 193 Patients with Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma

| No. of patients | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 107 |

| Female | 86 |

| T Category | |

| 1 | 130 |

| 2 | 45 |

| 3 | 13 |

| 4 | 5 |

| N Category | |

| N0 | 160 |

| N1 | 6 |

| N2 | 24 |

| N3 | 3 |

| Stage | |

| I | 145 |

| II | 18 |

| III | 30 |

| Recurrence | |

| Yes | 53 |

| No | 140 |

| Prognosis | |

| Dead | 37 |

| Alive (with recurrence) | 12 |

| Alive (with no recurrence) | 144 |

Figure 10.

Relation of NR0B1 expression to prognosis of clinical cases. A: OS in 193 lung adenocarcinoma cases. Five-year OS in all patients, patients with stage I, II, and III was 84.8%, 95.1%, 52.4%, and 53.8%, respectively. B: Five year DFS in all patients, patients with stage I, II, and III was 73.1%, 87.9%, 30.5%, and 23.4%, respectively. OS (C) and DFS (D) curves in NR0B1-hi and NR0B1-lo cases.

Among 193 lung adenocarcinoma cases, 105 cases (54.4%) were categorized as NR0B1-hi, and the remaining cases as NR0B1-lo. Correlation of NR0B1 expression level with clinical findings is shown in Table 2. The χ2 analysis revealed that the N category and tumor recurrence significantly correlated with high NR0B1 expression. Patients with NR0B1-lo tumor showed significantly better OS and DFS than those with NR0B1-hi tumors (P < 0.01, respectively) (Figure 10, C and D).

Table 2.

Correlation of NR0B1 Expression in Lung Adenocarcinoma with Clinicopathological Factors

| NR0B1

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hi | Lo | P value | |

| T Category | |||

| 1 | 73 | 57 | |

| 2 | 23 | 22 | |

| 3 | 7 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | 3 | 0.855 |

| N Category | |||

| N0 | 79 | 81 | |

| N1 | 5 | 1 | |

| N2 | 19 | 5 | |

| N3 | 2 | 1 | 0.021 |

| Stage of disease | |||

| I | 72 | 73 | |

| II | 12 | 6 | |

| III | 21 | 9 | 0.069 |

| Recurrence | |||

| Yes | 43 | 10 | |

| No | 62 | 78 | <0.01 |

Univariate analysis revealed that high T category, lymph node metastasis (high N category), advanced stage, large tumor size, and high NR0B1 expression were significant unfavorable factors for both 5-year OS and DFS (Table 3). Multivariate analysis revealed that the advanced stage, large tumor size, and high NR0B1 expression were independent prognostic factors for both 5-year OS and DFS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Prognostic Factors for Overall and Disease-Free Survivals

| OS

|

DFS

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate HR (95% CI) | P value | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | P value | Univariate HR (95% CI) | P value | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.001 (0.964–1.040) | 0.961 | 0.992 (0.963–1.021) | 0.566 | ||||

| Sex | 0.837 (0.413–1.698) | 0.623 | 0.795 (0.458–1.379) | 0.414 | ||||

| T Category | 2.005 (1.436–2.800) | <0.01 | 1.362 (0.809–2.291) | 0.245 | 1.830 (1.393–2.403) | <0.01 | 1.078 (0.687–1.690) | 0.744 |

| N Category | 2.442 (1.796–3.322) | <0.01 | 0.657 (0.306–1.411) | 0.282 | 2.408 (1.888–3.072) | <0.01 | 0.768 (0.418–1.411) | 0.395 |

| Stage | 2.982 (2.062–4.312) | <0.01 | 3.098 (1.187–8.084) | 0.021 | 2.959 (2.220–3.944) | <0.01 | 2.825 (1.350–5.913) | <0.01 |

| Tumor size | 1.046 (1.025–1.066) | <0.01 | 1.029 (1.004–1.055) | 0.021 | 1.041 (1.026–1.057) | <0.01 | 1.025 (1.005–1.045) | 0.014 |

| NR0B1 level | 0.083 (0.025–0.281) | <0.01 | 0.043 (0.009–0.195) | <0.01 | 0.208 (0.103–0.420) | <0.01 | 0.176 (0.078–0.397) | <0.01 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival.

Discussion

Patient characteristics such as gender, age, and 5-year OS in the present study were similar to those in the previous reports.37 In addition, the uni- and multivariate analyses showed the prognostic significance of clinicopathological factors, including tumor size and stage of disease, as reported previously.37 These findings indicate that the results obtained from the present clinical cases are commonly applicable.

CSCs are known to be enriched in SP,17,20 therefore proteins highly expressed in SP may become a candidate for CSC markers. Since the expression level of NR0B1 is higher in SP than in MP of lung adenocarcinoma cell line, NR0B1 might be further investigated as a candidate marker for CSCs of lung adenocarcinoma. The knocked down expression of NR0B1 resulted in the decrease of resistance against topotecan, Matrigel invasion, in vitro colony formation, and in vivo tumorigenic activities. The involvement of NR0B1 in the resistance against anti-cancer drugs and the high tumorigenicity was consistent with the higher rates of recurrence in the cases with NR0B1-hi than those with NR0B1-lo expression as shown in the clinical samples. In addition to recurrence, NR0B1-hi tumors showed the higher frequency of lymph node metastasis than that of NR0B1-lo tumors. Invasion of cancer cells into the surrounding tissues and high tumorigenic potential, which were characteristic to NR0B1-high population, are essential for the establishment of lymph node metastasis.38,39 Since NR0B1 is not expressed on the cell surface, the sorting of NR0B1-hi and NR0B1-lo populations in living cells is impossible. Because the experiment to examine whether NR0B1-him, but not NR0B1-lo, gives rise to both NR0B1-hi and -lo populations is not possible due to above-mentioned reason, it is difficult to assess directly whether NR0B1-hi population was CSCs or not. Still, the involvement of NR0B1 in the resistance against anti-cancer drug, invasiveness, and high tumorigenic potentials in A549 and PC-14 cell lines suggested that NR0B1 might be candidate marker for CSCs, or at least, for tumorigenic cells of lung adenocarcinoma.

Kinsey et al30 and Garcia-Aragoncillo et al40 reported that NR0B1 expression is related to cell proliferative activity in Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines. In contrast, the knocked-down expression of NR0B1 did not affect the cell proliferation of A549 cells. This might be attributable to the difference of cell types; Saito et al26 and Nakamura et al28 did not find any correlation of NR0B1 expression level with the Ki-67 labeling index, a well-established marker for cell proliferative activity, in the endometrial adenocarcinoma of uterus and prostate. The present study on the clinical cases of lung adenocarcinoma showed that NR0B1 expression level did not correlate with the size of tumors. NR0B1 appeared to play a role for cell proliferation in Ewing’s sarcoma but not in lung, endometrial, and prostatic adenocarcinomas.

The knocked down expression of NR0B1 had no effect on cell growth (assessed by cell number), but significantly affected tumorigenic and invasion abilities. The expression level of MMP-2 decreased in knocked-down cells, which may explain the low invasion ability. The defective anti-apoptotic ability of knocked-down cells as revealed decreased expression of Bcl-2 might explain the normal proliferation potential (cell growth), but low tumorigenicity. NR0B1 is reported to antagonize several transcription factors, including WT-1,41 which is known to suppress Bcl-2 promoter.42 NR0B1 might antagonize the function of WT-1, thereby enhancing Bcl-2 transcription. Although the precise mechanism remains to be clarified, the defective expression of Bcl-2 and MMP-2 could be causative for the low tumorigenic and invasion abilities of NR0B1 knocked-down cells.

The formation of SP was found even when the expression of NR0B1was reduced, indicating that NR0B1 was not necessary for SP formation. For SP formation, several chemical transporters, such as ABCG2, are involved.15,16,17 NR0B1 might not affect the expression of these chemical transporters.

In adenocarcinoma of uterine endometrium and prostate, NR0B1 was present in the nucleus, but not in the cytoplasm.26,28 Whereas, the subcellular localization of NR0B1 was various among cases with the present lung adenocarcinoma. Kawajiri et al43 reported that NR0B1 localization changed during pituitary development from nucleocytoplasmic at embryonic day 10.5 to nucleus at day 18.5. Helguero et al44 demonstrated that NR0B1 localized in the nucleus of mammary gland in virgin mice, nucleocytoplasmic in pseudopregnant mice, and cytoplasmic in lactating mice. To date, the functional heterogeneity of NR0B1 depending on the subcellular localization has not been clarified. Although no significant differences in clinicopathological findings were found among cases with these three staining patterns, further analysis with a larger number of cases is necessary to reveal the functional heterogeneity of NR0B1 depending on the subcellular localization.

Numerous CpG sequences around the NR0B1 promoter suggested the epigenetic regulation of its transcription. In fact, the promoter activity of NR0B1 significantly decreased when the CpG sequences were methylated in vitro. The proportion of CpG methylation was inversely correlated with the NR0B1 expression level in clinical samples. Very recently, Garcia-Aragoncillo et al40 reported that EWS/FLI1 directly binds to the GGAA-rich region in NR0B1 promoter and transactivates its activity. It is well known that transcription factors may bind to their cognate recognition sequences when the promoter region is relaxed in the unmethylated state.45 The promoter region of NR0B1 in Ewing’s sarcoma appeared to be relaxed, whereas in lung adenocarcinoma it possesses a packed promoter in the heavily methylated condition. Demethylation may enable some unknown transcription factors to bind and transactivate NR0B1 promoter in lung adenocarcinoma. Further studies are needed to clarify such transcription factors.

Taken together, NR0B1 was involved in resistance against anti-cancer drugs, invasion, in vitro colony formation, and in vivo tumorigenic potentials of lung adenocarcinoma cell line. NR0B1-hi cases showed the higher frequency of lymph node metastasis and tumor recurrence than those of NR0B1-lo cases. The high level of NR0B1 expression was an independent poor prognostic factor in the cases with lung adenocarcinoma.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Megumi Sugano, Ms. Etsuko Maeno, and Ms. Takako Sawamura for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Eiichi Morii, M.D., Department of Pathology, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University, Yamada-oka 2-2, Suita 565-0871, Japan. E-mail: morii@patho.med.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

There is no conflict of interest in this study.

References

- Heppner GH. Tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Res. 1984;44:2259–2265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemburger AW, Salmon SE. Primary bioassay of human tumor stem cells. Cell Sci. 1977;197:461–463. doi: 10.1126/science.560061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce WR, Van Der Gaag H. A quantitative assay for the number of murine lymphoma cells capable of proliferation in vivo. Nature. 1963;199:79–80. doi: 10.1038/199079a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard J, Sauvageau G. Bmi-1 determined the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:255–260. doi: 10.1038/nature01572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, Henkelman RM, Cusimano MD, Dirks PB. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AT, Berry PA, Hyde C, Stower MJ, Maitland NJ. Prospective identification of tumorigenic prostate cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10946–10951. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger , Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumor growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Peschle C, DeMaria R. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince ME, Sivanandan R, Kaczorowski , Wolf GT, Kaplan MJ, Dalerba P, Weissman IL, Clarke MF, Ailles LE. Identification of a subpopulation of cells with cancer stem cell properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:973–978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610117104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Heidt DG, Dalerba P, Burant CF, Zhang L, Adsav V, Wicha M, Clarke MF, Simeone DM. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1030–1037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumor stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:275–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou H, Dean M. Targeted therapy for cancer stem cells: the patched pathway and ABC transporters. Oncogene. 2007;26:1357–1360. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell MA, Brose K, Paradis G, Conner AS, Mulligan RC. Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1797–1806. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadnagy A, Gaboury L, Beaulieu R, Balicki D. SP analysis may be used to identify cancer stem cell populations. Exp Cell Res. 2006;14:387–391. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Setoguchi T, Taga T. Persistence of a small subpopulation of cancer stem-like cells in the C6 glioma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:781–786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307618100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setoguchi T, Taga T, Kondo T. Cancer stem cells persist in many cancer cell lines. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:414–415. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.4.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrawala L, Calhoun T, Schneider-Broussard R, Li H, Bhatia B, Tang S, Reilly JG, Chandra D, Zhou J, Claypool K, Coghlan L, Tang DG. Side population is enriched in tumorigenic, stem-like cancer cells, whereas ABCG2+ and ABCG2- cancer cells are similarly tumorigenic. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6207–6219. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global Cancer Statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo DC, Sung JM, Cho HJ, Yi H, Seo KH, Choi IS, Kim DK, Kim JS, El-Aty AMA, Shin HC. Gene expression profiling of cancer stem cell in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:75. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niakan KK, McCabe ER. DAX1 origin, function, and novel role. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;86:70–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmqvist L, Glover CH, Hsu L, Bossen B, Piret JM, Humphries RK, Helgason CD. Correlation of murine embryonic stem cell gene expression profiles with functional measures of pluripotency. Stem Cells. 2005;23:663–680. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niakan KK, Davis EC, Clipsham RC, Jiang M, Dehart DB, Sulik KK, McCabe ER. Novel role for the orphan nuclear receptor DAX1 in embryogenesis different from steroidogenesis. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;88:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S, Ito K, Suzuki T, Utsunomiya H, Akahira JI, Sugihashi Y, Niikura H, Okamura K, Yaegashi N, Sasano H. Orphan nuclear receptor DAX-1 in human endometrium and its disorders. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:645–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abd-Elaziz M, Akahira J, Moriya T, Suzuki T, Yaegashi N, Sasano H. Nuclear receptor DAX-1 in human common epithelial ovarian carcinoma: an independent prognostic factor of clinical outcome. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:980–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Suzuki T, Arai Y, Sasano H. Nuclear receptor DAX1 in human prostate cancer: a novel independent biological modulator. Endocr J. 2009;56:39–44. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k08e-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendiola M, Carrillo J, García E, Lalli E, Hernández T, de Alava E, Tirode F, Delattre O, García-Miguel P, López-Barea F, Pestaña A, Alonso J. The orphan nuclear receptor DAX1 is up-regulated by the EWS/FLI1 oncoprotein and is highly expressed in Ewing tumors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1381–1389. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey M, Smith R, Lessnick SL. NR0B1 is required for the oncogenic phenotype mediated by EWS/FLI in Ewing’s sarcoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:851–859. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morii E, Oboki K, Jippo T, Kitamura Y. Additive effect of mouse genetic background and mutation of MITF gene on decrease of skin mast cells. Blood. 2003;101:1344–1350. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slichenmyer WJ, Von Hoff DD. New natural products in cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:770–788. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1990.tb01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomicic MT, Christmann M, Kaina B. Topotecan-triggered degradation of topoisomerase I is p53-dependent and impacts cell survival. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8920–8926. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Siegler KL, Iczknowski KA, Leng L, Bucala R, Vera PL. Inhibition of macrophage migration inhibitory factor or its receptor (CD74) attenuates growth and invasion of DU-145 prostate cancer cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:8730–8739. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Burris TP, Zhang YH, Huang BL, Mason J, Copeland KC, Kupfer SR, Pagon RA, McCabe ERB. Genomic sequence of the DAX1 gene: an orphan nuclrear receptor responsible for X-linked adrenal hypoplasia congenital and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2481–2486. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.7.8675564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobin LH, Wittekind Ch, editors. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,; TNM Classification of malignant tumors. (5th ed.) 1997:pp 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Nagai K, Yoshida J, Nishimura M, Takahashi K, Yokose T, Nishiwaki Y. Conventional clinicopathologic prognostic factors in surgically resected nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:1976–1984. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991115)86:10<1976::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Tiede B, Massague J, Kang Y. Beyond tumorigenesis: cancer stem cells in metastasis. Cell Res. 2007;17:3–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabletz T, Jung A, Spaderna S, Hlubek F, Kirchner T. Opinion: migrating cancer stem cells—an integrated concept of malignant tumor progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:744–749. doi: 10.1038/nrc1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Aragoncillo E, Carrillo J, Lalli E, Agra N, Gómez-López G, Pestaña A, Alonso J. DAX1, a direct target of EWS/FLI1 oncoprotein, is a principal regulator of cell-cycle progression in Ewing’s tumor cell. Oncogene. 2008;27:6034–6043. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli E, Sassone-Corsi P. Dax-1, an unusual orphan receptor at the crossroads of steroidogenic function and sexual differentiation. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1445–1453. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt SM, Hamada S, McDonnell TJ, Rauscher FJ, 3rd, Saunders GF. Regulation of the proto-oncogenes bcl-2 and c-myc by the Wilms tumor suppressor gene WT1. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5386–5389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawajiri K, Ikuta T, Suzuki T, Kusaka M, Muramatsu M, Fujieda K, Tachibana M, Morohashi K. Role of the LXXLL-motif and activation function 2 domain in subcellular localization of Dax-1. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:994–1004. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helguero LA, Hedengran Faulds M, Förster C, Gustafsson JA, Haldosén LA. DAX-1 expression is regulated during mammary epithelial differentiation. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3249–3259. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP, Tycko B. The history of cancer epigenetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:143–153. doi: 10.1038/nrc1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]