Abstract

The α2β1 integrin receptor plays a key role in angiogenesis. Here we investigated the effects of small molecule inhibitors (SMIs) designed to disrupt integrin α2 I or β1 I-like domain function on angiogenesis. In unchallenged endothelial cells, fibrillar collagen induced robust capillary morphogenesis. In contrast, tube formation was significantly reduced by SMI496, a β1 I-like domain inhibitor and by function-blocking anti-α2β1 but not -α1β1 antibodies. Endothelial cells bound fluorescein-labeled collagen I fibrils, an interaction specifically inhibited by SMI496. Moreover, SMI496 caused cell retraction and cytoskeletal collapse of endothelial cells as well as delayed endothelial cell wound healing. SMI activities were examined in vivo by supplementing the growth medium of zebrafish embryos expressing green fluorescent protein under the control of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 promoter. SMI496, but not a control compound, interfered with angiogenesis in vivo by reversibly inhibiting sprouting from the axial vessels. We further characterized zebrafish α2 integrin and discovered that this integrin is highly conserved, especially the I domain. Notably, a similar vascular phenotype was induced by morpholino-mediated knockdown of the integrin α2 subunit. By live videomicroscopy, we confirmed that the vessels were largely nonfunctional in the absence of α2β1 integrin. Collectively, our results provide strong biochemical and genetic evidence of a central role for α2β1 integrin in experimental and developmental angiogenesis.

Angiogenesis is the formation of new capillaries from pre-existing blood vessels and is essential for human development, wound healing, and tissue regeneration.1 Angiogenesis is dependent on interactions of endothelial cells with growth factors and extracellular matrix components.2,3 Endothelial cell-collagen interactions are thought to play a role in angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro and require the function of the α1β1 and α2β1 integrins,3 two receptors known to cross talk.4 Thus, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced angiogenesis in Matrigel plugs implanted in mice is markedly inhibited by anti-α1β1 and -α2β1 integrin antibodies.5,6 Studies using various collagen-induced angiogenesis assays also suggest a critical role for endothelial cell α2β1 integrin2,7,8 binding to the GFPGER502–507 sequence of the collagen triple helix.9 Consistent with these findings, endorepellin, a potent anti-angiogenic molecule derived from the C terminus of perlecan10,11 disrupts α2β1 integrin function,12,13,14,15,16 and some of the affected gene products have been associated with the integrin-mediated angiogenesis.17 Endothelial cell-collagen interactions may also contribute to tumor-associated angiogenesis.18 For example, gene products up-regulated in tumor-associated endothelial cells include types I, III, and VI collagens,19 and tumor-associated angiogenesis is sensitive to endorepellin treatment.15,20,21

Interestingly, α2β1 integrin-null mice show no overt alteration in either vasculogenesis or angiogenesis but display only a mild platelet dysfunction phenotype and altered branching morphogenesis of the mammary glands.22,23 This observation suggests that in mammals, there is functional compensation during development, but that α2β1 integrin might be required for postnatal angiogenesis. Indeed, when adult α2β1-null mice are experimentally challenged, they show an enhanced angiogenic response during wound healing24 and tumor xenograft development.15,25

The α1β1 and α2β1 integrins include inserted domains (I domains) in their α subunits that mediate ligand binding.26,27 The α2 I domain is composed of a Rossman fold and a metal ion coordination site (MIDAS), proposed to ligate the GFPGER502–507 sequence of collagen, thereby inducing receptor activation.26,28 Other integrin domains may also play a role in ligand binding and receptor activation. For example, the β1 I-like domain seems to allosterically modulate collagen ligation by the α2 I domain, and, intracellularly, the cytoplasmic sequence of the α2 subunit functions as a hinge, locking the receptor in an inactive conformation, and membrane-soluble peptide mimetics of this sequence were shown to promote α2β1 receptor activation.29 Recently, a family of small molecule inhibitors (SMIs)2 targeting the function of the α2β1 integrin were designed.30 Specifically, inhibitors of α2β1 integrin function were prepared using modular synthesis, enabling substitutions of arylamide scaffold backbones with various functional groups, creating SMIs targeted to the I domain or the intact integrin.30,31,32 In this study, we tested the activities of a group of SMIs on endothelial cell-collagen interactions and angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. We provide evidence that SMI496, which binds between the I domains of β1 and α2 subunits,32 interferes with α2β1 integrin activity on endothelial cells both in vitro and in vivo, suggesting a potential therapeutic modality to interfere with angiogenesis. Moreover, interference with α2 integrin expression in embryonic zebrafish caused a vascular phenotype characterized by abnormal angiogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Small Molecule Inhibitors

SMIs were prepared using either solid-phase or solution-phase synthesis as described previously.30 Final products were purified by preparative reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography using a GRACEVYDAC C-18 column and characterized by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and electrospray ionization high-resolution mass spectroscopy.

Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cell Isolation and Culture

Umbilical cords were obtained from the Labor and Delivery Department, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital. Endothelial cells were isolated from the cords as described previously.9 Endothelial cells were cultured on tissue culture flasks coated with 0.2% gelatin. Cells were fed complete media (Medium 199 [GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 50 μg/ml endothelial cell growth supplement, 50 μg/ml heparin sodium salt from porcine intestinal mucosa (grade I-A, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 1.0% penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.1% Fungizone (GIBCO). Endothelial cell growth supplement was isolated from bovine hypothalami.9 Endothelial cells were used through passage 6.

In Vitro Angiogenic Assays

For branching morphogenesis assays using a collagen sandwich, endothelial cells were plated at 105 cells/cm2/well onto 12-well plates coated with 100 μg/ml type I collagen in 10 mmol/L acetic acid at 25 μg/cm2. Cells were then incubated overnight at 37°C and allowed to reach confluence. The next day the cells were rinsed and an apical collagen gel was applied to each well at 100 μl/cm2 (control wells received an equivalent volume of cold serum-free media). The collagen gel was made by mixing 70% 1.5 mg/ml type I collagen in 10 mmol/L acetic acid, 10% 10× culture salts, and 20% 11.8 mg/ml sodium bicarbonate. After the gel was added, the plates were incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C to allow the gel to polymerize. After polymerization, warm serum-free media plus growth factors (VEGF and fibroblast growth factor-2, 5 ng/ml each; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA),9 and any test agents were added to the wells. The cells were returned to the 37°C incubator, and micrographs were taken at 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours after gel addition. For branching morphogenesis assays on Matrigel, endothelial cells were untreated or treated in suspension for 10 minutes with 50 to 100 nmol/L SMI496 or dimethyl sulfoxide. Endothelial cells were plated in complete media at 105 cells/well onto a four-well chamber slide precoated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and incubated at 37°C. Tube formation was assayed over the course of 3 to 4.5 hours.

Endothelial Cell Growth and Migration Assays

Endothelial cells were cultured on 96-well tissue culture plates at 104 cells/well overnight. Cell growth was then examined for 4 days in the presence of complete culture medium, culture medium lacking endothelial cell growth supplement, and heparin and complete culture medium plus SMI496, 488, 394, and 355, and an anti-α2β1 function-blocking antibody (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). Cell numbers were determined at various times by staining the cultures with crystal violet and extracting the dye with Triton X-100. The soluble dye was measured (A590) using a SpectraMax 340PC microplate reader and SoftMax Pro 5 software to determine cell number based on endothelial cell standard curves. For cell migration, endothelial cells were plated at 105 cells/cm2/well onto 12-well plates coated with 100 μg/ml type I collagen in 10 mmol/L acetic acid at 25 μg/cm2. On the third day, a “scrape wound” was made across the center of the well by dragging a 200-μl plastic pipette tip through the cell monolayer. The cells were rinsed with Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) and resupplemented with complete medium plus test agents. At various time points micrographs were taken of the wound area.

Flow Cytometry

This assay was adapted from a published protocol.29 Endothelial cells, passages 4 to 6, were trypsinized and allowed to recover for 2 hours under serum-free conditions. After washing, the cells were treated with chemical inhibitors or inhibitory antibodies at concentrations of 50 and 100 μg/ml, respectively, in PBS+/1% bovine serum albumin. Without removing the inhibitors, collagen labeled with fluorescein 5-isothiocyanate (FITC) Sigma-Aldrich) was then added to cells at 50 μg/ml. A final incubation with 7-amino-actinomycin D (Sigma-Aldrich) allowed the detection of dead cells. Cells were then analyzed on a Beckman Coulter EPICS flow cytometer. The CD2 antibody and SMI723 were used to obtain baseline measures of FITC-collagen staining for the function blocking antibody and SMI496, respectively. The proportion of cells binding FITC-collagen at baseline was set to 1.0 for each group, and the effect of inhibitors was expressed as a ratio of the percentage of cells binding FITC-collagen in the presence of inhibitors divided by the percentage of cells binding FITC-collagen in the presence of a control inhibitor or antibody.

Endothelial Cell Attachment to Collagen Substrata

Endothelial cells were cultured on type I collagen films and exposed to conditioned medium or conditioned medium including SMI496 at 50 μg/ml for 30 minutes. The cells were then fixed with 4.0% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained with phalloidin-FITC to visualize actin stress fibers and counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole to visualize nuclei.

Zebrafish Studies

We used wild-type or transgenic zebrafish expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under control of the VEGF receptor 2 (vegfr2-gfp)33 or fli promoter (fli1a:nEGFPy7)34. Embryos were housed within the zebrafish facility of Thomas Jefferson University and were raised at 28.5°C according to standard practice. Embryos were generated by natural pair-wise crossing, and all developmental staging was reported as days postfertilization (dpf). For in vivo zebrafish SMI angiogenesis assays, stock solutions of SMI496 and 355 (1.0 mg/ml) in water were directly added to zebrafish embryo medium to reach a final concentration of 4, 20, and 50 μmol/L, a range used previously to study small molecule anti-angiogenic compounds such as SU5416 and SU6668.33 All experiments were repeated two times using at least 40 embryos per treatment. For the characterization of zebrafish α2 integrin, RT-PCR was performed on cDNA derived from pools of staged embryos (n = 50 embryos per group). Integrin α2 was detected using α2 forward primer 5′-CAGAGAATCGTTGGAGGGAAACTG-3′ and α2 reverse primer 5′-CGATTAGCCTGATAGAGTTTGTTGG-3′ (Invitrogen). PCR reactions were performed as described previously.35 For the knockdown of zebrafish integrin α2, a morpholino (Gene Tools, LLC, Philomath, OR) was designed to target the 5′-untranslated region/translation start of zebrafish integrin α2 (α2-MO). The morpholino sequence was 5′-CCAGTAGAATCACAGCCTTTTCCAT-3′. The standard control morpholino sequence was 5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′. The p53 co-knockdown experiment was performed to eliminate off-target morpholino effects as described previously.36 Morpholinos (1–10 ng/embryo) were microinjected into one-cell wild-type or vascular transgenic embryos according to the standard protocol.37 Subintestinal vessel development was assayed by endogenous alkaline phosphatase staining as described previously.35 Embryos were studied on a Leica MZFIII stereomicroscope equipped with an Axiocam camera (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) and AxioVision software version 3.0.6.1, a Leica MZ16FA stereomicroscope equipped with a DFC500 camera and Application Suite version 2.5.0.r1 (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) or a Leica DM5500 B equipped with a DFC340 FX camera and LAS AF version 1.6.1 (Leica). Embryos were imaged in embryo media or 3 to 4% methyl cellulose and anesthetized with tricaine. Images were assembled using Adobe Photoshop CS2.

Statistical Analysis

All data were graphed and analyzed using the Sigma Plot and Sigma Stat software package. Statistical analysis between groups was assessed by Student’s t-test. The data were considered statistically significant with P < 0.05.

Results

The goal of these experiments was to examine whether SMIs designed to disrupt α2β1 integrin function would also influence integrin-collagen binding and collagen-induced or native angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo and to examine the role of α2β1 integrin in developmental angiogenesis.

Selection of Small Molecule Inhibitors

We selected a variety of compounds as positive and negative controls for these studies. Compound SMI496 is a prototype inhibitor for α2β1, with an IC50 for inhibition of platelet association to collagen I of approximately 10 nmol/L and was identified in a screen for compounds that inhibit α2β1-dependent adhesion of platelets to collagen30 (Figure 1). SMI146 is highly selective for α2β1 relative to α1β1, α4β1, α5β1, αvβ3, and αIIbβ3. Compound SMI488, a close analog of SMI496, has at least 100-fold lower affinity for α2β1. The compounds SMI355, 394, 418, and 723 were very weakly active (affinities in the mid-mmol/L range), were ultimately found to act nonspecifically, and were used as negative controls.

Figure 1.

Structure of small molecule inhibitors of the α2β1 integrin receptor. Low Mr (<600 Da) benzene scaffold derivatives designed to bind and functionally disrupt the α2β1 integrin receptor. Inhibitors and their receptor target sites include the following: SMI355, 394, and 418, α2I domain; SMI488 and 723 (not shown) negative controls; and SMI496, β1I-like domain.

Effects of SMIs on Endothelial Cell Branching Morphogenesis

For these studies, angiogenesis was induced by an apical type I collagen gel placed on a confluent endothelial cell monolayer. In control cultures at 0 hours, cells are confluent, and after collagen gel addition, at 2 to 4 hours, cell movement and reorganization of the cell layer occurs; at 6 to 8 hours, cultures are about 50% reorganized; and at 12 to 24 hours, capillary tube formation is complete (Figure 2A). We have shown previously by electron microscopy that these tubes contain bona fide lumina.9 In contrast, cultures exposed to SMI496 or the anti-α2β1 integrin antibody, but not to negative control SMIs, exhibited only a slight amount of cell movement and reorganization with very few gaps in the cell layer at all time points. Effects of the SMIs on angiogenesis at various times up to 24 hours after collagen gel addition were quantified, confirming that only SMI496 and the anti-α2β1 integrin antibody significantly (P < 0.001) inhibited tube formation in three independent experiments (Figure 2B). Examination of branching morphogenesis on Matrigel revealed that SMI496 did not block endothelial cell tube formation on this substrate (supplemental Figure S1, see http://ajp.amipathol.org).

Figure 2.

Disruption of collagen-induced in vitro capillary morphogenesis by SMI496, an inhibitor of α2β1-integrin function. A: Photomicrographs of live endothelial cells undergoing in vitro capillary morphogenesis in serum-free defined media supplemented with VEGF-fibroblast growth factor-2 (5 ng/ml each) ± SMI496 (100 nmol/L). Note the complete block of capillary-like formation by SMI496, clearly visible at 24 hours. Similar results were obtained with an anti-α2β1 integrin function-blocking antibody (5 μg/ml). No effect was observed with any of the other SMIs (not shown). Scale bar = ∼100 μm. B: Quantification of three independent experiments similar to that shown in A. Each experiment was run in triplicate. Values represent the mean ± SE. Notice that only SMI496 is capable of blocking capillary formation (***P < 0.001). A similar inhibition was also evoked by an anti-α2β1 integrin function-blocking antibody. Angiogenic areas were measured using the ImageJ program.

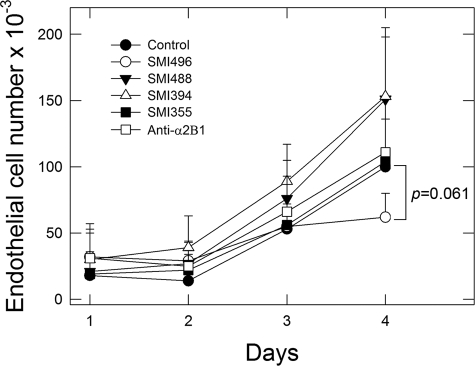

Effects of SMIs on Endothelial Cell Growth

To ensure that the SMI496 effects were not due to cytotoxicity, we performed growth experiments in which endothelial cells were challenged with the various SMIs. The results showed no significant effect on cell growth by any of the SMIs for the first 2 days of culture (Figure 3), which exceeds the 1-day treatment period in which SMI496 exerts its potent anti-angiogenic activity (Figure 2). Thereafter, there was some inhibition of growth evoked by SMI496 and growth promotion exerted by several other compounds (Figure 3). Thus, SMI496 does not seem to be cytotoxic or growth-active within the time frame that it is inhibitory to angiogenesis.

Figure 3.

Effects of SMIs on growth. Notice the lack of growth inhibition by all of the SMIs tested. By 4 days a borderline (P = 0.061) inhibition of cell growth by SMI496 was observed. Values represent the mean ± SE of three independent experiments run in triplicate. Endothelial cells were supplemented daily with fresh media containing the various SMIs (all at ∼100 nmol/L) or 10 μg/ml of an anti-α2β1 integrin function-blocking antibody. On each day, plates were fixed with glutaraldehyde and on day 4, all cultures were stained with crystal violet, the dye was detergent extracted, and cell number was determined spectrophotometrically.

SMI496 Disrupts Endothelial Cell-Collagen Interactions

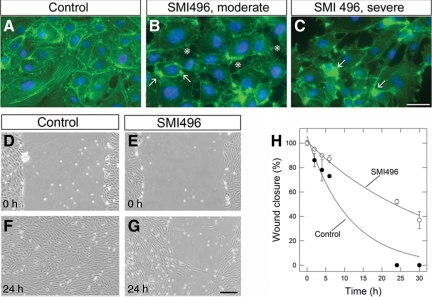

Next, we examined the effect of SMIs on endothelial cell interactions with type I collagen fibrils, either in suspension or immobilized on tissue culture plates. To study the interaction of collagen fibrils in suspension with endothelial cells, type I collagen fibrils were labeled with FITC such that they retained the capacity to promote angiogenesis in vitro (data not shown). Thus, under control conditions, approximately 80% of endothelial cells bound to FITC-collagen. Collagen binding was inhibited ∼65% by SMI496 or the α2β1 function blocking antibody (P < 0.001) but not by SMI723 or an anti-CD2 antibody (Figure 4; supplemental Figure S2, see http://ajp.amipathol.org). When type I collagen was immobilized, endothelial cells displayed a well-spread cell morphology and a normal actin cytoskeleton with distinct and numerous cytoplasmic filamentous actin bundles (Figure 5A). However, treatment with SMI496 disrupted endothelial cell-collagen interactions: the cells were substantially less well spread and actin was now present in a punctate pattern indicative of a collapse of the actin cytoskeleton (Figure 5, B and C, arrows).

Figure 4.

Effects of SMIs on endothelial cell-collagen fibril ligation in suspension. Note that SMI496 but not the negative compound SMI723 disrupts FITC-labeled collagen binding. The anti-α2β1 integrin function-blocking antibody but not an anti-CD2 blocking antibody has a similar effect. For flow cytometry studies, endothelial cells were trypsinized, allowed to recover for 2 hours, and then exposed to SMIs (50 nmol/L) or antibodies (100 μg/ml) in PBS ± 1% bovine serum albumin. FITC-collagen (50 μg/ml) was then added. Cell-FITC collagen interactions were analyzed on a Beckman Coulter EPICS flow cytometer. Anti-CD2 antibody and the negative control SMI723 were used to obtain baseline measures of FITC-collagen staining. Values represent the mean ± SE from three independent experiments run in triplicate (***P < 0.001, by Student’s t-test). Scatterplots are found in Supplemental Figure S2, see http://ajp.amipathol.org.

Figure 5.

Effects of SMIs on endothelial cell attachment to collagen substrata and migration. Fluorescent micrographs of endothelial cells cultured on type I collagen treated for 30 minutes with either vehicle (A) or SMI496 (100 nmol/L) (B and C). The arrows point to the collapse and coalescence of actin bundles. The asterisks point to areas of endothelial cell retraction. The cells were fixed, detergent-permeabilized, and stained with phalloidin-FITC (green) to visualize actin stress fibers and counterstained with DAPI (blue) to visualize nuclei. Note the partial collapse of the actin cytoskeleton (arrows, B and C). The experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Scale bar = 20 μm. D–G: Light micrographs of “wounded” endothelial monolayers and the effect of SMI496. Confluent endothelial cell layers on collagen films were scraped with a 200-μl pipette tip. The cells were rinsed with PBS and resupplemented with either media alone or media supplemented with SMI496 (100 nmol/L). Micrographs were taken at various time points. Scale bar = 100 μm. H: Quantification of endothelial cell wound closure over time. The areas within the scratches were quantified using ImageJ software and expressed as percentage of wound closure at time 0. Values represent the mean ± SE of two independent experiments run in triplicate.

SMI496 Affects Endothelial Cell Migration

The effect of SMI496 on endothelial cell migration was tested using a scratch wound assay in which the ability of endothelial cells to migrate into the wounded area of a confluent culture was measured over time (Figure 5, D and E). At 24 hours, control cultures showed growth into the wound area (Figure 5F). However, endothelial cell migration was substantially delayed by adding SMI496 to the culture medium (Figure 5G). Quantification of two independent experiments performed in triplicate showed a t1/2 of ∼8 hours for control wound closure compared with a t1/2 of ∼24 hours for the SMI496-treated cultures (P < 0.001) (Figure 5H).

SMI496 Disrupts Zebrafish Developmental Angiogenesis

There is a significant degree of conservation between the β1 I-like domains of the zebrafish and mammalian integrins.38 We therefore predicted a similar interaction between zebrafish integrin β1 I-like domain and SMI496. Accordingly, we studied the effect of SMI496 on angiogenesis in vivo using zebrafish. To monitor vascular development in vivo and over real time, we used a vascular transgenic zebrafish expressing green fluorescent protein under the control of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 promoter (vegfr2-gfp).33 In contrast with the axial vessels (dorsal aorta and posterior cardinal vein), which form by vasculogenesis, the intersegmental vessels (ISVs), dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessels, and parachordal vessels develop through angiogenesis.39,40,41 Embryos treated with 4 or 20 μmol/L SMI496 developed normally but showed significant and dose-dependent suppression of ISV development compared with those treated with vehicle alone (Figure 6, A–I). Often, the endothelial cells failed to migrate along the myosepta from the dorsal aorta (>80%, n = 160 in two separate experiments) and followed abnormal paths, failing to interconnect and form the regular lattice of vessels present on either side of the trunk (Figure 6, F and I, arrows). Consequently, the dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessels were poorly formed or absent in the embryos treated with SMI496. In contrast, the negative control SMI, SMI355, at 30 μmol/L caused no significant changes in developmental angiogenesis (n = 80) (Figure 6, M–O). To determine whether the effects of SMI496 were reversible, zebrafish embryos were treated as before for 4 hours, and then were rinsed and allowed to recover in fresh embryo medium for an additional 3 days. The results indicated significant recovery of the vascular phenotype in ∼85% (n = 80) of the treated embryos (Figure 6, J and K). However, a minority of the embryos (∼12%) showed either incomplete recovery or a significant continuing inhibition of vascular sprouting (Figure 6L). Similar results were seen in the cranial vessels (supplemental Figure S3, see http://ajp.amipathol.org). Collectively, these results corroborate the in vitro function of SMI496 and further indicate that this small compound acts at a crucial stage of developmental angiogenesis without significantly affecting vasculogenesis.

Figure 6.

SMI496 inhibits angiogenesis in the zebrafish trunk. A–C: Bright-field and fluorescent micrographs of live vegfr2-gfp zebrafish controls at 2 dpf. Note the proper formation of the major axial vessels, dorsal aorta (DA), and posterior cardinal vein (PCV), as well as the inter-segmental vessels (ISVs) and the dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessel (DLAV). D–I: Representative embryos treated from 7 hpf to 2 dpf with SMI496 at the indicated concentrations. Note the abnormal and stunted formation of the intersegmental vessels (arrows in F and I) and the absence of the dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessel. J–L: Representative images of partial recovery after removal of SMI496 from the embryo medium and subsequent growth for an additional 3 days in compound-free water. M–O: Representative fluorescent images of live vegfr2-gfp transgenic zebrafish at 2 dpf treated with SMI355 at the designated concentrations for 4 hours starting at 7 hpf. Note normal vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. All panels are oriented with rostral to the left and all lateral views are from the left side. Scale bars = ∼300 μm.

Characterization of Zebrafish α2 Integrin Subunit

To assess the role of α2 integrin during zebrafish vascular development we began by characterizing Danio rerio integrin α2. Our analysis of the available zebrafish genome revealed the presence of a single gene (itga2) encoding zebrafish α2 integrin (chromosome 10). We found that the itga2 gene (gene identification number: 100151619) maintains conserved synteny with the human and mouse integrin α2 genes (supplemental Figure S4A, see http://ajp.amipathol.org). By RT-PCR, using Danio rerio itga2-specific primers, we detected mRNA/expression of itga2 throughout zebrafish embryogenesis (supplemental Figure S4B, see http://ajp.amipathol.org). The expression pattern indicates maternal contribution of α2 at early time points (<3 hours postfertilization [hpf]) and the initiation and increase of zygotic expression over time (supplemental Figure S4B, see http://ajp.amipathol.org). Our results are supported by zebrafish itga2 gene expression profiling data (supplemental Figure S4C, see http://ajp.amipathol.org).42 The predicted zebrafish integrin α2 protein exhibit overall 49 and 47% identities with the human and mouse counterparts, respectively (supplemental Figure S5, see http://ajp.amipathol.org). Comparison of the α2 I domain alone revealed 57% identity between fish, human, and mouse species (underlined regions, supplemental Figure S5, see http://ajp.amipathol.org).

Zebrafish α2 Integrin and Vascular Development

To examine the role of α2 integrin during blood vessel formation in vivo we applied a morpholino knockdown approach. We designed a translation blocking morpholino targeting the 5′-untranslated region and translation start of zebrafish itga2. Microinjection of 1 to 10 ng of morpholino (α2-MO) was capable of inducing a similar and dose-dependent phenotype (Figure 7, A–E). The α2 morphant phenotype was characterized by generalized twisting of the body associated with a curly tail (Figure 7B). We found similar results using the vascular transgenic and wild-type embryos. We eliminated morpholino off-target effects due to p53 activation by co-knockdown with p53-MO (supplemental Figure S6, see http://ajp.amipathol.org). We verified α2 knockdown by assessing the total α2 protein levels of the morphant via whole-mount immunostaining (supplemental Figure S7, see http://ajp.amipathol.org). Consistent with the SMI496 treatment, analysis of 1.5 dpf α2 morphant embryo vascular development revealed substantial inhibition of developmental angiogenesis (Figure 7). We found a significant defect in ISV development associated with a total decrease in the branching morphogenesis of the caudal venous plexus (Figure 7, F–I). A closer examination revealed that these vessels were largely nonfunctional in the absence of α2. Concurrently, by using the Tg(fli1a:nEGFP)y7, a transgenic zebrafish in which endothelial cell nuclei are labeled with a GFP containing the nuclear localization sequence,34 we found a significant reduction in endothelial cell number at the level of the deficient sprouting. These results suggest that a functional integrin α2β1 is also required for endothelial cell proliferation (supplemental Figure S8, see http://ajp.amipathol.org). By live differential interference contrast videomicroscopy, we found that the partially formed vessels contained little to no red blood cell circulation (supplemental Videos SV1 to SV3, see http://ajp.amipathol.org). Additional analysis of angiogenic subintestinal vessel development at 3 dpf also revealed that the α2 knockdown inhibited subintestinal vessel formation (Figure 8, A–E). Overall, these results indicate a central role for α2 integrin during angiogenic blood vessel formation.

Figure 7.

Characterization of the α2 morphant phenotype. A: Representative bright-field image of four 1.5 dpf control embryos. B: Representative bright-field image of six matched α2-MO injected embryos. C: Control vasculature as visualized by GFP and corresponding to the embryos presented in A. D: α2 morphant vasculature corresponding to the embryos presented in B. Note the defect in trunk and tail angiogenesis. E: Summary of the dose-response relationship between morpholino injection amount and overall phenotypic penetrance. Scale bar = 1 mm. α2 knockdown inhibits multiple aspects of developmental angiogenesis. F–I: Fluorescent micrographs of live vegfr2-gfp zebrafish embryos focusing on the vasculature at 1.5 dpf of control and integrin α2 morphant embryos. F: Representative control trunk to tail region exhibiting complete formation of the axial vessels, ISVs and caudal venous plexus (CV). G and H: morphant trunk regions exhibiting abnormal ISV development. I: Representative morphant tail region exhibiting abnormal CV development. Scale bars = ∼200 μm.

Figure 8.

α2 knockdown disrupts angiogenic subintestinal vessel (SIV) development. A: Representative control embryo displaying clear formation of the subintestinal vessels by 3 dpf. B–D: Matched α2 morphant embryos exhibiting inhibition of subintestinal vessel formation in a dose-dependent manner. All vessels were visualized by endogenous alkaline phosphatase staining. Scale bar = 250 μm. E: Graphic summary of the number of subintestinal vessel plexus intersection points. Data are the mean ± SD of 10 embryos/dose from two independent experiments.

Discussion

The α2β1 integrin plays key roles in hemostasis and endothelial cell biology; yet, few inhibitors of the receptor have been identified. Inhibitors include function blocking antibodies3,9,43 and aromatic polyketides from Streptomyces, proposed to bind the closed conformation of the α2I domain, coordinating with the magnesium ion and neighboring residues of the MIDAS adhesion site.44 These compounds block α2I domain-collagen binding, and the adhesion of integrin-expressing Chinese hamster ovary cells to type I collagen. The snake venom protein rhodocetin binds to the α3–α4 loop and adjacent α helices in the α2β1 integrin-collagen binding site and blocks integrin-collagen interactions.45,46 The C-lectin type snake venom protein EMS16 binds the α2I domain, blocking collagen-induced platelet aggregation and endothelial cell migration in collagen.47 Saratin, from the leech, also disrupts platelet α2I domain-collagen interactions.48 As alternatives to these natural products, families of small molecule inhibitors of integrin function have recently been developed.30,44 Those used in the present study target α2β1 integrin I domain function and are patterned after peptide-mimetic inhibitors of other integrins. These compounds have greater potencies and specificities than inhibitors of this integrin studied previously.30

To assay the effects of the SMIs on in vitro angiogenesis, we used a method replicating capillary tube formation, the last stage of angiogenesis. Thus, confluent endothelial cell monolayers cultured in a serum-free defined medium, including fibroblast growth factor-2 and VEGF1659 and overlaid with a collagen gel, form capillary-like tubes within 12 to 24 hours. In this assay SMI496, which binds between the I domains of β1 and α2 subunits,32 inhibited capillary tube formation by approximately 60 to 70% whereas the negative control compounds had very little effect. Notably, the level of inhibition of angiogenesis by SMI496 was nearly identical to that exhibited by an anti-α2β1 integrin function blocking antibody, or triple helical peptides containing the integrin-binding GFPGER502–507 sequence.9 It is possible that incomplete inhibition of angiogenesis occurs, because another integrin or class of receptors besides the α2β1 integrin may contribute to collagen-induced angiogenesis. However, contributions of the α1β1 and αvβ3 integrins to collagen-induced angiogenesis have been ruled out in this system.9

In cell proliferation studies, SMI496 either failed to affect endothelial cell growth for up to 3 days in culture or exhibited minor inhibitory effects at later times. The fact that SMI496 showed no evidence of toxicity and was active in our rapid serum-free angiogenesis assay in which cell proliferation probably plays little, if any, role,9 suggests that the slight activity of SMI496 on cell growth may not be mechanistically related to its anti-angiogenic activity.

The effects of SMIs on endothelial cell-collagen interactions were next examined using flow cytometry. Endothelial cell binding to collagen was markedly inhibited by SMI496 or an anti-α2β1 integrin function blocking antibody. Moreover, SMI496 disrupted endothelial cell interactions with substrate-bound collagens, as evidenced by reduced cell-substratum interactions accompanied by an apparent collapse of the actin cytoskeleton. These data imply that SMI496 may disrupt endothelial cell-α2β1 integrin-collagen ligation and perhaps even displace α2β1 integrins already bound to collagen. Notably, the activity of SMI496 is reminiscent of that of endorepellin, a fragment of perlecan, which binds to the α2β1 integrin and disrupts its function.16,21 Lastly, endothelial cell migration on collagen was delayed by SMI496, even in the presence of a growth inhibitor. Thus, SMI496 inhibits endothelial cell collagen binding, migration on collagen, and collagen-induced capillary morphogenesis, but with little effect on proliferation.

To examine the activities of SMI496 on in vivo angiogenesis we used the zebrafish, owing to their rapid embryonic development and their transparency, permitting direct in vivo observation of vascular development. In addition, the zebrafish model is amenable to the testing of small molecules49,50,51,52 and screening of angiogenic compounds supplemented to the embryo media.33,53 To monitor vascular development, we used the vascular vegfr2-gfp transgenic zebrafish harboring endothelial-specific expression of GFP.33 Embryos treated with 4 to 30 μmol/L SMI496 developed normally, but showed significant and dose-dependent suppression of ISVs compared with vehicle alone. Our results indicate that the biological effects of SMI496 are partially reversible and very specific for sprouting blood vessels for several reasons. First, the development of the major axial vessels was not altered, and therefore it seems that SMI496 does not affect vasculogenesis. Second, on removal of SMI496, most of the embryos recovered to near normality, indicating that the endothelial cells in the dorsa aorta and parachordal vessel are still capable of migrating and forming fully functional blood vessels. Our results further indicate there is a precise window of time during which SMI496 exerts its biological activity, because little or no suppression of angiogenesis was observed when treatment began at 1 dpf (data not shown). Notably, by this time the major axial vessels are completely formed, circulation has commenced, and ISVs begin sprouting from the DA. These findings further strengthen the hypothesis that SMI496 might indeed function as an inhibitor of the α2β1 integrin. Therefore, these findings demonstrate an in vivo role for the α2β1 integrin in regulating trunk and cranial angiogenesis and suggest that there is a specific window in development during which this integrin is required for proper sprouting angiogenesis, where endothelial cells need to migrate and anastomose to form functional arteriovenous plexuses.

Our analysis of the zebrafish integrin α2 subunit revealed a number of significant points. First, gene expression profile data revealed maternally derived itga2 expression (<3 hpf). These data suggested the importance of α2 during early embryonic development and clearly indicated the onset of zygotic transcriptional activity at later time points. Second, analysis of the integrin α2 amino acid sequence indicated an evolutionarily conserved α2 within zebrafish and an especially well-conserved I domain. Third, morpholino knockdown of α2 implied a central requirement for embryo viability. We have found a significant amount of embryo lethality by 1 dpf, suggesting that α2 is required for proper development. We believe only embryos exhibiting a partial knockdown are therefore able to survive at later time points. Accordingly, our whole-mount immunostaining revealed partial knockdown because certain portions of the embryo body were nearly devoid of positive staining, whereas other regions remained reactive. Finally, our analysis of vascular development in α2 integrin morphant embryos supported a central role for α2 during sprouting angiogenesis in the trunk and tail and branching morphogenesis of the caudal vein. In addition, α2 morphants exhibited a significant decrease in endothelial cell number, suggesting an important role for α2 integrin in endothelial cell proliferation. These results are the first to implicate integrin α2 during developmental angiogenesis.

In summary, we show for the first time that SMI496 inhibits endothelial cell-collagen binding, migration on collagen, and collagen-induced angiogenesis. SMI496 functionally disrupts α2β1 by binding between the I domain of α2 and the I-like domain of β1 subunits, thereby allosterically inhibiting α2β1 integrin function. This would be the first report implicating a role for the β1 I-like domain in angiogenesis. Although SMI496 may function by disrupting cell-collagen ligation, it remains to be seen whether it also influences α2β1 activation or clustering, two other components of integrin function and signaling. Our results suggest that SMI496 and related compounds may have significant therapeutic potential. Thus, because of their small size, SMIs should be highly diffusible and easily delivered to target tissues. In tissue stroma, SMIs are predicted to arrest angiogenesis when endothelial cells attempt to engage type I collagen fibrils to initiate capillary tube formation. Yet, SMI496 should not affect endothelial cell homeostasis and viability. SMIs are thus attractive candidates as therapies to combat pathological changes including tumor growth and metastasis, in which angiogenesis plays a prominent role. Finally, the discovery that the partial knockdown of integrin α2 causes a phenotype characterized by abnormal and nonfunctional angiogenic sprouting, both in the trunk and cephalic region, underlines a key functional role for this receptor during developmental angiogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy L. Rubinstein (Zygogen, Atlanta, GA) for providing the vascular transgenic (vegfr2-gfp) zebrafish, Shiu-Ying Ho for valuable advice, Angela McQuillan for expert technical assistance, and George Purkins for help with the video files.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Renato V. Iozzo, M.D. Department of Pathology, Anatomy and Cell Biology, Room 249 JAH, 1020 Locust St., Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA 19107. E-mail: iozzo@mail.jci.tju.edu.

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants RO1 CA39481, RO1 CA47282 and RO1 CA120975 to R.V.I.), RO1 HL53590 to J.S.A., and PO1 HL62250 to J.S.B. J.J.Z. was supported by National Research Service Award training grant T32 AA07463.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

A guest editor acted as editor-in-chief for this manuscript. No person at Thomas Jefferson University was involved in the peer review process or final disposition for this article.

References

- Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:15–18. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Senger DR. Endothelial extracellular matrix: biosynthesis, remodeling, and functions during vascular morphogenesis and neovessel stabilization. Circ Res. 2005;97:1093–1107. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000191547.64391.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Senger DR. Extracellular matrix mediates a molecular balance between vascular morphogenesis and regression. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:197–203. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282fcc321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abair TD, Sundaramoorthy M, Chen D, Heino J, Ivaska J, Hudson BG, Sanders CR, Pozzi A, Zent R. Cross-talk between integrins α1β1 and α2β1 in renal epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:3593–3604. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger DR, Claffey KP, Benes JE, Perruzzi CA, Sergiou AP, Detmar M. Angiogenesis promoted by vascular endothelial growth factor: regulation through α1β1 and α2β1 integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13612–13617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger DR, Perruzzi CA, Streit M, Koteliansky VE, de Fougerolles AR, Detmar M. The α1β1 and α2β1 integrins provide critical support for vascular endothelial growth factor signaling, endothelial cell migration, and tumor angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64363-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Camarillo CW. An α2β1 integrin-dependent pinocytic mechanism involving intracellular vacuole formation and coalescence regulates capillary lumen and tube formation in three-dimensional collagen matrix. Exp Cell Res. 1996;224:39–51. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan MC, Senger DR. Collagen I initiates endothelial cell morphogenesis by inducing actin polymerization through suppression of cyclic AMP and protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:327–334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney SM, DiLullo G, Slater SJ, Martinez J, Iozzo RV, Lauer-Fields JL, Fields GB, San Antonio JD. Angiogenesis in collagen I requires α2β1 ligation of a GFP*GER sequence and possible p38 MAPK activation and focal adhesion disassembly. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30516–30524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304237200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongiat M, Sweeney S, San Antonio JD, Fu J, Iozzo RV. Endorepellin, a novel inhibitor of angiogenesis derived from the C terminus of perlecan. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4238–4249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez EM, Reed CC, Bix G, Fu J, Zhang Y, Gopalakrishnan B, Greenspan DS, Iozzo RV. BMP-1/Tolloid-like metalloproteases process endorepellin, the angiostatic C-terminal fragment of perlecan. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7080–7087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bix G, Fu J, Gonzalez E, Macro L, Barker A, Campbell S, Zutter MM, Santoro SA, Kim JK, Höök M, Reed CC, Iozzo RV. Endorepellin causes endothelial cell disassembly of actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesions through the α2β1 integrin. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:97–109. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bix G, Iozzo RA, Woodall B, Burrows M, McQuillan A, Campbell S, Fields GB, Iozzo RV. Endorepellin, the C-terminal angiostatic module of perlecan, enhances collagen-platelet responses via the α2β1 integrin receptor. Blood. 2007;109:3745–3748. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bix G, Iozzo RV. Matrix revolutions: “tails” of basement-membrane components with angiostatic functions. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodall BP, Nyström A, Iozzo RA, Eble JA, Niland S, Krieg T, Eckes B, Pozzi A, Iozzo RV. Integrin α2β1 is the required receptor for endorepellin angiostatic activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2335–2343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708364200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV. Basement membrane proteoglycans: from cellar to ceiling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:646–656. doi: 10.1038/nrm1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoeller JJ, Iozzo RV. Proteomic profiling of endorepellin angiostatic activity on human endothelial cells. Proteome Sci. 2008;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R. Basement membranes: structure, assembly and role in tumor angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:422–433. doi: 10.1038/nrc1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Croix B, Rago C, Velculescu V, Traverso G, Romans KE, Montgomery E, Lal A, Riggins GJ, Lengauer C, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Genes expressed in human tumor endothelium. Science. 2000;289:1197–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bix G, Castello R, Burrows M, Zoeller JJ, Weech M, Iozzo RA, Cardi C, Thakur MT, Barker CA, Camphausen KC, Iozzo RV. Endorepellin in vivo: targeting the tumor vasculature and retarding cancer growth and metabolism. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1634–1646. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bix G, Iozzo RV. Novel interactions of perlecan: unraveling perlecan’s role in angiogenesis. Microsc Res. 2008;71:339–348. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtkötter O, Nieswandt B, Smyth N, Müller W, Hafner M, Schulte V, Krieg T, Eckes B. Integrin α2-deficient mice develop normally, are fertile, but display partially defective platelet interaction with collagen. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10789–10794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Diacovo TG, Grenache DG, Santoro SA, Zutter MM. The α2 integrin subunit-deficient mouse: a multifaceted phenotype including defects of branching morphogenesis and hemostasis. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:337–344. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64185-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweers MC, Davidson JM, Pozzi A, Hallinger R, Janz K, Quondamatteo F, Leutgeb B, Krieg T, Eckes B. Integrin α2β1 is required for regulation of murine wound angiogenesis but is dispensable for reepithelialization. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:467–478. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall-Culbreath KD, Li Z, Zutter MM. Crosstalk between the α2β1 integrin and c-Met/HGF-R regulates innate immunity. Blood. 2008;111:3562–3570. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley J, King SL, Bergelson JM, Liddington RC. Crystal structure of the I domain from integrin α2β1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28512–28517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley J, Knight CG, Farndale RW, Barnes MJ, Liddington RC. Structural basis of collagen recognition by integrin α2β1. Cell. 2000;101:47–56. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80622-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley J, Knight CG, Farndale RW, Barnes MJ. Structure of the integrin α2β1-binding collagen peptide. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:1019–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Walle GR, Vanhoorelbeke K, Majer Z, Illyes E, Baert J, Pareyn I, Deckmyn H. Two functional active conformations of the integrin α2β1, depending on activation condition and cell type. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36873–36882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Vilaire G, Marcinkiewicz C, Winkler JD, Bennett JS, DeGrado WF. Small molecule inhibitors of integrin α2β1. J Med Chem. 2007;50:5457–5462. doi: 10.1021/jm070252b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Gerlach LO, Miller MW, Moore DT, Liu D, Vilaire G, Bennett JS, DeGrado WF. Arylamide derivatives as allosteric inhibitors of the integrin α2β1/type I collagen interaction. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:3380–3382. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Basra S, Kulp DW, Billings PC, Choi S, Beavers MP, McCarty OJT, Zou Z, Kahn ML, Bennett JS, DeGrado WF. Small-molecule inhibitors of integrin α2β1 that prevent pathological thrombus formation via an allosteric mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:719–724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811622106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross LM, Cook MA, Lin S, Chen J-N, Rubinstein AL. Rapid analysis of angiogenic drugs in a live fluorescent zebrafish assay. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:911–912. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000068685.72914.7E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siekmann AF, Lawson ND. Notch signalling limits angiogenic cell behaviour in developing zebrafish arteries. Nature. 2007;445:781–784. doi: 10.1038/nature05577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoeller JJ, McQuillan A, Whitelock J, Ho S-Y, Iozzo RV. A central function for perlecan in skeletal muscle and cardiovascular development. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:381–394. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robu ME, Larson JD, Nasevicius A, Beiraghi S, Brenner C, Farber SA, Ekker SC. p53 activation by knockdown technologies. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasevicius A, Ekker SC. Effective targeted gene ‘knockdown’ in zebrafish. Nat Genet. 2000;26:216–220. doi: 10.1038/79951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mould AP, McLeish JA, Huxley-Jones J, Goonesinghe AC, Hurlstone AFL, Boot-Handford RP, Humphries MJ. Identification of multiple integrin β I homologs in zebrafish (Danio rerio). BMC Cell Biol. 2006;7:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-7-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs S, Chen J-N, Garrity DM, Fishman MC. Patterning of angiogenesis in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 2002;129:973–982. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.4.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isogai S, Horiguchi M, Weinstein BM. The vascular anatomy of the developing zebrafish: an atlas of embryonic and early larval development. Dev Biol. 2001;230:278–301. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isogai S, Lawson ND, Torrealday S, Horiguchi M, Weinstein BM. Angiogenic network formation in the developing vertebrate trunk. Development. 2003;130:5281–5290. doi: 10.1242/dev.00733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang M, Garnett AT, Han TM, Hama K, Lee A, Deng Y, Lee N, Liu H-Y, Amacher SL, Farber SA, Ho S-Y. A web based resource characterizing the zebrafish developmental profile of over 16,000 transcripts. Gene Expr Patterns. 2008;8:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eble JA. Collagen-binding integrins as pharmaceutical targets. Curr Pharm Design. 2005;11:867–880. doi: 10.2174/1381612053381738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käpylä J, Pentikäinen OT, Nyrönen T, Nissinen L, Lassander S, Jokinen J, Lahti M, Marjamäki A, Johnson M, Heino J. Small molecules designed to target metal binding site in the α2I domain inhibits integrin function. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2742–2746. doi: 10.1021/jm070063t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eble JA, Niland S, Dennes A, Schmidt-Hederich A, Bruckner P, Brunner G. Rhodocetin antagonizes stromal tumor invasion in vitro and other α2β1 integrin-mediated cell functions. Matrix Biol. 2002;21:547–558. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(02)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eble JA, Tuckwell DS. The α2β1 integrin inhibitor rhodocetin binds to the A-domain of the integrin α2 subunit proximal to the collagen-binding site. Biochem J. 2003;376:77–85. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinkiewicz C, Lobb RR, Marcinkiewicz MM, Daniel JL, Smith JB, Dangelmaier C, Weinreb PH, Beacham DA, Niewiarowski S. Isolation and characterization of EMS16, a C-lectin type protein from Echis multisquamatus venom, a potent and selective inhibitor of the α2β1 integrin. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9859–9867. doi: 10.1021/bi000428a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TC, Berny MA, Robinson DK, Yin H, DeGrado WF, Hanson SR, McCarty OJT. The leech product saratin is a potent inhibitor of platelet integrin α2β1 and von Willebrand factor binding to collagen. FEBS J. 2007;274:1481–1491. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RT, Link BA, Dowling JE, Schrieber SL. Small molecule developmental screens reveal the logic and timing of vertebrate development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12965–12969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RT, Mably JD, Chen J-N, Fishman MC. Convergence of distinct pathways to heart patterning revealed by the small molecule concentramide and the mutation heart-and-soul. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1481–1491. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00482-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C-T, Johnson SL. Small molecule-induced ablation and subsequent regeneration of larval zebrafish melanocytes. Development. 2006;133:3563–3573. doi: 10.1242/dev.02533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RT, Shaw SY, Peterson TA, Milan DJ, Zhong TP, Schreiber SL, MacRae CA, Fishman MC. Chemical suppression of a genetic mutation in a zebrafish model of aortic coarctation. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nbt963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Bayliss PE, Wood JM, Roberts TM. Dissection of angiogenic signaling in zebrafish using a chemical genetic approach. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:257–267. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.