Abstract

Purpose

This paper discusses a novel approach for treatment of lexical retrieval deficits in aphasia in which treatment begins with complex, rather than simple, lexical stimuli. This treatment considers the semantic complexity of items within semantic categories, with a focus on their featural detail.

Methods and Results

Previous work on training items within animate categories (Kiran & Thompson, 2003a) and preliminary work aimed at items within inanimate categories are discussed in this paper. Both these studies indicate that training atypical category items that entail features inherent in the category prototype as well as distinctive features that are not characteristic of the category prototype results in generalization to untrained typical examples which entail only features consistent with the category prototype. Conversely, training typical examples does not result in generalization to untrained atypical examples. In this paper, it is argued that atypical items are more complex than typical items within a category and a theoretical framework for this dimension of semantic complexity is discussed. Then, evidence from treatment studies that support this complexity hierarchy is presented. Potential patient- and stimulus- specific factors that may influence the success of this treatment approach are also discussed.

Conclusions

The applications of semantic complexity to treatment of additional semantic categories and functional applications of this approach are proposed.

Introduction

This paper discusses applications of the Complexity Account of Treatment Efficacy (Thompson, Shapiro, Kiran, & Sobecks, 2003) to treatment of lexical semantic deficits in individuals with fluent aphasia. While complexity in the syntactic domain (see Thompson & Shapiro, this issue) and phonological domain (see Geirut, this issue) can be conceptualized in terms of a fairly systematic hierarchical organization of a system with constituent sub-elements, complexity in the semantic domain is less transparent. This paper will be restricted to discussion of semantic complexity within the realm of organization of semantic categories and the relevance of semantic complexity to treatment of naming deficits in aphasia. Specifically, semantic complexity is discussed with regard to three parameters, (a) atypical examples consist of core and more distinctive features compared to typical examples, which consist of core and shared prototypical features and fewer distinctive features, (b) as a group, features of typical examples comprise a subset of features of atypical examples, and (c) atypical examples are represented further away (in time and space) from the category prototype and typical examples within a multidimensional vector space representing a category. Based on these parameters we propose a complexity hierarchy based on item typicality. Following this theoretical discussion, we present results of studies experimentally examining the effects of treatment that proceeds from complex to simple category items (i.e., atypical to typical) compared to treatment that proceeds from simple to complex items (i.e., typical to atypical).

Because this approach to treatment of naming in aphasia is novel, this paper will also identify factors that may influence its success. As will be reviewed, both the nature of the typical and atypical stimuli and the way that their featural detail are exploited as part of the treatment methodology appear to influence the effectiveness of treatment. Further, the application of typicality hierarchies to treatment of various types of naming deficits seen in aphasia and corresponding evidence will be reviewed. Finally, applications of semantic complexity in developing treatments for other semantic categories will be proposed and relevant evidence will be discussed.

Theoretical Framework

Representation of semantic categories

The empirical basis for focusing on semantic features of target items to facilitate improved lexical access arises from our current understanding of the representation of semantic concepts. One principle of language organization is that the lexicon is organized by semantic categories, and within each category, examples are represented in a semantic space in terms of semantic attributes (see McRae, de Sa, & Siedenberg, 1997; Tyler, Moss, Durrant-Peatfield, & Levy, 2000; Tyler & Moss, 2001 for elaborations of these proposals). There is, however, considerable debate regarding the nature and representation of semantic attributes within each category, and the differences between categories. Most data exploring semantic organization of categories come from neuropsychological evidence of individuals with selective living/nonliving category impairments (see Forde & Humphreys, 1999; Hart, Moo, Segal, & Kraut, 2002; Moore & Price, 1999; Saffran & Schwartz, 1994 for reviews).

On some accounts these broad categories are dissociable on the basis of their semantic features. For instance, the Weighted Overlappingly Organized Features model (WOOF; Lambon-Ralph, Patterson, & Hodges, 1997) suggests that all concepts are represented in a central amodal network of semantic features and that individual items have differential weightings on the types of features that determine the concept of the object. Accordingly, natural categories of living things are differentially weighted towards visual/sensory features, whereas nonliving categories are differentially weighted towards functional/locative attributes. Similar views have been proposed by the Organized Unitary Content Hypothesis (OUCH; Caramazza, Hillis, Rapp, & Romani, 1990) which suggests an amodal semantic system in which similar concepts tend to cluster together by virtue of their shared attribute structure.

In a more complex model proposed by Tyler and colleagues (Tyler et al., 2000; Tyler & Moss, 2001), concepts are represented in an amodal unitary semantic system with the distinctiveness of features varying across living and nonliving domains and interaction occurring between functional and perceptual features. In living categories, functional features pertain to the way in which exemplars interact with the environment (e.g., a duck flies) and often have associated sensory features (e.g., a duck has wings). Such features are usually shared between category members and therefore, are strongly correlated. Living things also share distinctive features that distinguish one member from another (e.g., a tiger has stripes), and these are less correlated with other members (Tyler et al., 2000). In contrast, nonliving items have fewer properties that tend to be more distinctive than those of living things. Supportive empirical evidence for these hypotheses also comes from McRae et al. (1997), who found that normal healthy adults generated significantly more functional information for nonliving categories than living categories, and conversely, significantly more intercorrelated features for living categories than nonliving categories. Hence, representations of living things are more densely connected and tend to cluster together more closely in semantic space than nonliving things.

Likewise, Garrard, Lambon-Ralph, Hodges, and Patterson (2001) developed a database of semantic features based on features generated for specific items across several categories by normal participants. Generated features were then classified as sensory (e.g. a duck has webbed feet), functional (e.g. a duck can fly), or encyclopedic (e.g. a duck is found near water), and analyzed with regard to their dominance (frequency of elicitation for a given item) and distinctiveness (the percent of category members for which the feature was characteristic). Results showed that living categories were associated with a higher ratio of sensory to functional features, a higher intercorrelation between features, and a greater proportion of shared features among typical items in living categories than nonliving categories.

Finally, Sartori and Lombardi (2004) propose a model of semantic memory in which concepts are represented by vectors of semantic features, each of which has an associated relevance weight that reflects the level of contribution to the core meaning of the concept. Therefore, has trunk is a semantic feature of higher relevance for elephant than has four legs. Sartori and Lombardi found that examples from living categories had lower relevance values than examples from nonliving categories, however, this effect disappeared when relevance values were matched across categories.

Most of the aforementioned theories are aimed at explaining the distinction between animate and inanimate category features and do not elaborate on the featural detail inherent in items within specific categories. When describing the features of examples within a specific semantic category, it is important to note that not all items within a category are treated equally, and category inclusion is influenced by the perceived typicality of items, that is how closely category items fit a particular category prototype.

Semantic categories and typicality

Evidence that typicality influences access to category items stems from Rosch's (1975) seminal work examining typicality ratings of items within categories. Results of this work showed a graded ranking of items within a category that was consistent across participants. Further support for the notion that atypical examples (e.g., ostrich) have a different status within a category (e.g., bird) than typical examples (e.g., robin) came from work showing that participants name typical items more often than atypical ones when asked to generate names of items within categories (Mervis, Caitlin, & Rosch, 1976). Studies examining verification times for category membership (Hampton, 1979; McCloskey & Glucksberg, 1979; Kiran & Thompson, 2003b; Larochelle & Pineu, 1994; Rips, Shoben, & Smith, 1973; Smith, Shoben, & Rips, 1974; Storms, De Boek, & Ruts, 2000) and category naming frequency (Casey, 1992; Hampton, 1995), as well as data detailing the order in which category items are learned (Posner & Keele, 1968; Rosch, 1973; Rosch & Mervis, 1975) indicate the advantage of typical examples over atypical examples within a category. For instance, during online category verification of animate categories (e.g., birds, vegetables; Kiran & Thompson, 2003b) and inanimate categories (e.g., clothing, furniture; Kiran, Ntourou, & Eubank, 2005a), typical examples were responded to faster than atypical examples. Also, during online feature verification tasks, where participants are required to judge whether a specific feature (e.g., does this bird live in the wild) matches a corresponding picture (e.g., vulture), features for typical examples were verified faster than features for atypical examples (Kiran & Allison, 2005).

This effect, known as the typicality effect, is also seen in participants with nonfluent aphasia (Grober, Kellar, Perecman, & Brown, 1980; Grossman, 1980, 1981; Kiran & Thompson, 2003b). For example, Kiran & Thompson (2003b) showed that participants with nonfluent aphasia (like normal participants), had faster reaction times for typical, as compared to atypical, items in a category verification task. Interestingly, however, participants with fluent aphasia did not show this pattern.

Numerous theories have been proposed to explain the typicality effect in normal individuals (for a review see Komatsu, 1992). Of these, prototype/family resemblance models (Hampton, 1979; 1993, 1995; Rosch & Mervis, 1975) are, in principle, similar to the semantic organization theories discussed above. A category prototype is a generic representation of the common features of the category taken as a whole. Therefore, across categories, there are a set of features that exert differential weights in the definition of a prototype (Hampton, 1995). Prototype theories propose that similarity to the prototype increases with the number of matching features and hence, typical examples consist primarily of prototypical features. The less similar the example is to the prototype, the less typical the item. Further, Rosch and Mervis (1975) found that the degree to which a given member possessed attributes in common with other members was highly correlated with the degree to which it was rated typical of the category, that is, typical members (e.g., robin) shared more features with other birds (e.g., wren, finch), whereas, atypical members (e.g., ostrich) shared fewer features with other examples of birds. Consequently, similarity judgments of a category would place typical examples closer to the center of a semantic space (prototype) and atypical examples furthest away from the prototype (Rosch & Mervis, 1975). This assumption of prototype models is in line with conceptual structure models which suggest that typicality is determined by similarity in features to the category prototype. Further, results of Garrard et al.'s (2001) study provide evidence that typicality ratings are related to the number of shared features between an exemplar and prototype concept for a given category, supporting Rosch's prototype theory.

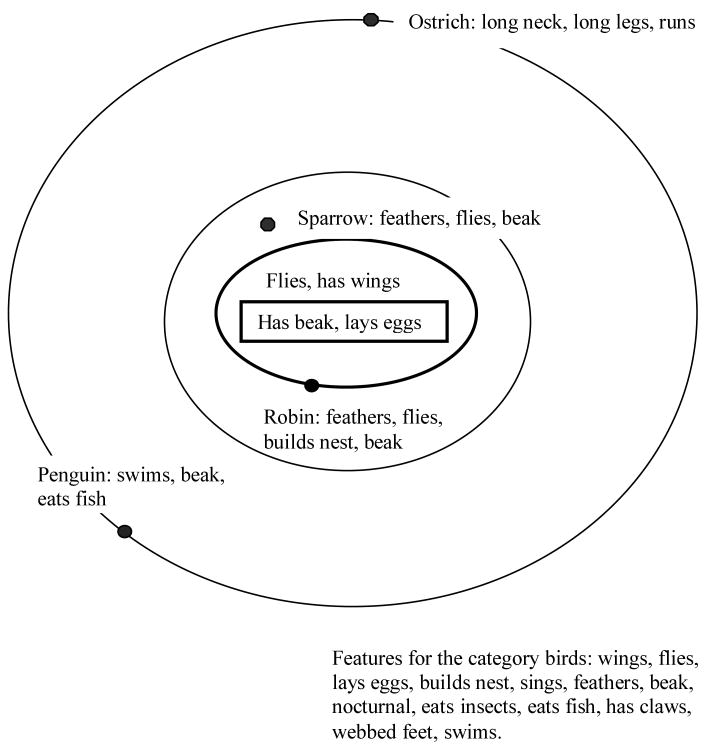

Category Typicality and Semantic Complexity

So, how does the discussion of category structure and the co-existent typicality effect translate into semantic complexity? Elaborating on the previous discussion, some hypotheses are postulated. As shown in Figure 1, each category consists of some core features, those that are required for category membership (e.g., bird: has beak, lays eggs). All members of the category possess these features whereas nonmembers (e.g., animals) do not possess these attributes. Apart from that, the category consists of a central prototype, or the idealized set of features (e.g., flies, has wings, builds nest). Typical examples within the category possess more prototypical features (e.g., small, hops, lives in trees) and fewer distinctive features (e.g., long neck, big beak). Also typical examples have a number of shared/intercorrelated features with other typical examples (e.g., small and hops are shared by sparrow, robin, wren, finch, see Figure 1). Therefore, these features carry less weight within the category as they are shared by a number of other typical examples (see Hampton, 1993; 1995; Kiran & Allison, 2005). In contrast, atypical examples such as ostrich and penguin also contain the core features of the category (e.g., has wings, has beak); however, they have fewer prototypical features (e.g., flies, lives in trees). Atypical examples, instead, possess more distinctive features shared by fewer examples in the category (e.g., long legs, long neck, runs) that emphasize the variation of features that are permissible in the category, and hence, carry more weight in the representation of these examples than typical examples within the category (Hampton, 1993; Kiran & Allison, 2005). That is, ostrich still has a beak, lays eggs, but does not fly or live in trees. Instead, an ostrich can run, has long legs, and a long neck. It should be noted here that these feature descriptions are not restricted to birds but are applicable to other natural categories as shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical model of category representation in terms of semantic attributes illustrates typical examples represented at the center of semantic space and atypical examples represented at the periphery of this space. The center of this space represents the core of the category and surrounding it are the prototypical features. Typical examples (e.g., robin, sparrow) primarily consist of prototypical features whereas atypical examples (e.g., penguin, ostrich) primarily consist of distinctive features.

Table 1. Examples of stimuli and semantic features used for birds, clothing and vegetable categories.

| Bird | Typical | Atypical |

|---|---|---|

| Examples: | Robin, Sparrow, Wren | Ostrich, Penguin, Vulture |

| Core features | Lays eggs, has wings, has beak | |

| Prototype features | Small, hops, flies, lives in trees | |

| Distinctive features | Long legs, webbed feet, long neck | |

| Clothing | Typical | Atypical |

| Examples: | Shirt, Suit, Blouse | Apron, Suspenders, Bib |

| Core features | Worn on body, made of fabric | |

| Prototype features | Has buttons, zippers | |

| Distinctive features | Decorative accessory, protective covering | |

| Vegetable | Typical | Atypical |

| Examples: | Cucumber, Carrot, Radish | Garlic, Pumpkin, Parsley |

| Core features | Found in grocery store, nutritious | |

| Prototype features | Eaten fresh, put in salad | |

| Distinctive features | Eaten cooked, strong smell | |

Given these differences in the featural detail of items within a category, a semantic complexity hierarchy can be derived. Atypical items are arguably more complex than typical items, because the features of typical items are in a subset relation to that of atypical items. This is because atypical examples entail core features (e.g., lays eggs, has beak), distinctive features (e.g., runs, long legs, long neck), as well as occasional prototypical features (e.g., flies, lives in trees) and thereby necessarily consist of a wider range of features than do typical examples (see Table 1). In contrast, typical examples mostly consist of core and prototypical features. This hierarchy also is supported by the extensive evidence of longer reaction times for atypical examples compared to typical examples during category verification tasks as discussed above (Hampton, 1979; Kiran & Thompson, 2003b; Kiran et al., 2005; Larochelle & Pineu, 1994; McCloskey & Glucksberg, 1978; Rips et al., 1973; Smith et al., 1974). These data suggest that atypical examples are inherently more difficult to judge than typical examples as being members of a category, presumably because they represent a wider network of features than typical examples (for an analogous proposal equating processing time with complexity see Gennari & Poeppel, 2003).

To summarize, atypical examples are more complex than typical examples because: (a) atypical examples consist of core and more distinctive features (and therefore exert more weight) compared to typical examples which consist of core and shared prototypical features (resulting in lesser weights) and fewer distinctive features, (b) as a group features of typical examples comprise a subset of the features of atypical examples, and (c) atypical examples are represented further away (in time and space) from the category prototype and typical examples within a multidimensional vector space representing the category.

Semantically based naming treatment

Numerous researchers have examined recovery of naming in individuals with aphasia (Maher & Raymer, 2004; Nickels 2002). Several of these studies have manipulated semantic variables of target stimuli (Davis & Pring, 1991; Greenwald, Raymer, Richardson, & Rothi, 1995; Howard, Patterson, Franklin, Orchid-Lisle, & Morton, 1985; Marshall, Pound, White-Thomson, & Pring, 1990; Marshall, Robson, Pring, & Chiat, 1998; Nickels & Best, 1996; Pring, Hamilton, Harwood, & McBride, 1993). However, many of these studies have found little generalization to untrained items. Notably, studies focused on strengthening the semantic attributes of target items have been more successful at facilitating generalization to untrained items (Boyle, 2004; Boyle & Coehlo, 1995; Coehlo, McHugh, & Boyle, 2000; Drew & Thompson, 1999; Kiran & Thompson, 2003a; Lowell, Beeson, & Holland, 1995). Whereas some of these studies have focused on generalization to items within a superordinate category (Drew & Thompson, 1999), others have also observed generalization to items across semantic categories (Boyle, 2004; Boyle & Coehlo, 1995; Coehlo et al., 2000; Lowell et al., 1995).

Typicality in treatment of naming

The potential relevance of semantic complexity to treatment was first shown in a connectionist simulation by Plaut (1996). A connectionist network with four layers-orthographic, intermediate, semantic and clean up was utilized. The training set consisted of 100 artificial “words” (set of binary values). To generate the semantic features, a semantic prototype was created by randomly setting a set of semantic features (or binary values) with a high probability of becoming active. The representation of individual words was then generated by randomly changing some of the features of the prototype. Therefore, typical words shared most of the features of the prototype and atypical words shared far fewer features with the prototype. After the network was trained to recognize words, it was lesioned by removing some randomly selected proportions of connections. The retraining procedure indicated greater generalization of typical words when atypical words were trained, whereas retraining of typical words generalized only to other typical words, and performance of atypical words deteriorated.

Results from two studies, one investigating animate categories (Kiran & Thompson, 2003a) and another preliminary study investigating inanimate category examples (Kiran, Ntourou, Eubank, & Shamapant, 2005) extend Plaut's findings to treatment for lexical retrieval deficits in participants with fluent aphasia. Each study individually examined the effects of item typicality on naming in either animate categories (e.g., birds, vegetables) or inanimate categories (e.g., clothing, furniture) as there is sufficient evidence to suggest that animate and inanimate categories are processed differently. As discussed above, there exists a difference in the semantic attributes accessed for the predominantly form-based animate categories (e.g., has legs) compared to the predominantly function-based inanimate categories (e.g., used for cutting) (Devlin et al., 2002). This has significant implications for naming treatments that are based on semantic features.

In both experiments, individuals with aphasia presenting with naming deficits participated in a semantically based naming treatment program. Treatment focused on improving either typical or atypical items within two semantic categories, and generalization was tested for untrained items of the category. The Kiran and Thompson study also used stimuli of intermediate typicality that consisted of examples with typicality ratings in between those of typical and atypical examples. The order of typicality and category trained was counterbalanced across participants in each experiment. For instance, in the Kiran and Thompson study (2003a), two participants (MB and MR) received treatment for atypical examples and demonstrated generalization to untrained intermediate and typical examples in both categories. Two other participants (AJ and JH) received treatment for typical items and demonstrated improvements on the trained typical items, but improvements on the untrained intermediate and atypical examples were not observed until those items were directly trained.

For participant JH, the treatment design was modified to further illustrate the effects of the item typicality. Specifically, this participant, first trained on typical examples of birds, which resulted in no generalization to untrained intermediate and atypical examples was subsequently trained on atypical examples of the second category (e.g., vegetables) which resulted in improvements on the trained atypical examples as well as on the untrained intermediate and typical examples.

The same procedure was employed in another study recently completed in our laboratory focused on inanimate categories (Kiran et al., 2005b), including clothing and furniture. Five participants, three individuals with fluent aphasia, and two individuals with nonfluent aphasia/apraxia participated in the experiment. As in the previous study, the order of typicality and category were counterbalanced across the five participants. In general, the participants with fluent aphasia responded better to treatment than those with nonfluent aphasia. As shown in Table 2, in three participants (ML, RC, and GG), generalization from trained atypical examples to untrained typical examples was observed. Likewise, in four participants (ML, KO, RC, and BL), generalization did not occur from trained typical examples to untrained atypical examples.

Table 2. Summary of participant demographic information and the resulting generalization patterns observed across two experiments. WAB AQ refers to the Western Aphasia Battery Aphasia Quotient (Kertesz, 1982).

| Participant | Age (years) | Pre tx WAB AQ | Time post onset CVA (months) | Aphasia Type | Category Trained | Generalization trends | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animate categories | |||||||

| JH | 64 | 43.4 | 99 | Fluent | Birds | Typical ≠› Atypical | |

| Vegetables | Atypical => Typical | ||||||

| MB | 63 | 50.9 | 13 | Fluent | Birds | Atypical => Typical | |

| Vegetables | Atypical => Typical | ||||||

| AJ | 72 | 70 | 9 | Fluent | Vegetables | Typical ≠› Atypical | |

| MR | 75 | 46.4 | 14 | Fluent | Vegetables | Atypical => Typical | |

| Birds | Atypical => Typical | ||||||

| Inanimate categories | |||||||

| ML | 55 | 56.7 | 9 | Fluent | Clothing | Atypical => Typical | |

| Furniture | Typical ≠› Atypical | ||||||

| KO | 77 | 72.5 | 7 | Fluent | Furniture | Typical ≠› Atypical | |

| RC | 47 | 46.4 | 9 | Nonfluent | Clothing | Typical ≠› Atypical | |

| Furniture | Atypical => Typical | ||||||

| BL | 63 | 62.2 | 7 | Fluent | Furniture | Atypical ≠› Typical | |

| Clothing | Typical ≠› Atypical | ||||||

| GG | 50 | 37 | 8 | Nonfluent | Furniture | Atypical => Typical | |

Note: => indicates generalization noted, ≠› indicates no generalization observed

All participants demonstrated notable improvements on standardized language measures that were conducted prior to and after treatment. All of these participants with the exception of MB and RC demonstrated improvements of 8-10 points on the Western Aphasia Battery Aphasia Quotient (WAB AQ, Kertesz, 1982), reflecting a general improvement in language processing and production skills. Further, specific improvements (5% changes or more) were also observed in auditory comprehension and semantic processing abilities, both of which were directly addressed in treatment. One process all participants underwent during treatment was making explicit judgments about semantic features that were both imageable (e.g., does it have wings, is it green in color?) and nonimageable (e.g., is it a predator, is it nutritious? (see Table 3, step 3&4)). Therefore, improvements observed during treatment resulted in the ability to perform analogous semantic judgments on novel semantic tasks.

Table 3. Hypothesized component processes involved for each of the steps in the treatment.

| Step | Description | Processes involved |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Naming picture | See the picture of ostrich and name it | Visual processing, lexical access, phonological encoding |

| 2. Sorting pictures by target category | Sort 60 examples into three categories, birds, animals, musical instruments | For each category, employ a criteria for acceptable/unacceptable members of the category |

| 3. Selection of six semantic features of target item | For ostrich, select runs, has legs, reject flies | Active manipulation of semantic features of the target item; select features that are applicable to target example and reject those that are applicable to the category but not the example |

| 4. Answering 15 Yes/No questions | Five features belong to the target example, five belong to the category but not applicable to example, five not applicable to category | Active manipulation of semantic features of the target item through the auditory modality. Also requires participants to reject features not belonging to category |

| 5. Naming picture | See the picture of ostrich and name it | Lexical access following reinforcement of semantic features |

An explanation of the complexity effect

Why does training more complex, atypical, category items result in generalization to typical items, but the converse training arrangement (training less complex, typical items) does not influence production of atypical items? To explain the potential mechanisms underlying the effect of typicality treatment, it is worthwhile to briefly review theoretical models of word retrieval. Most theoretical models of naming agree that lexical access can be broadly divided into two processes, namely, semantic and phonological processes. These models, however, fall along a continuum when addressing the details pertaining to the relative timing of lexical access.

One view of naming proposes two sequential components to lexical access, lexical selection followed by phonological encoding (Butterworth, 1989, 1992; Levelt, 1989, Levelt, Roelofs, & Meyer, 1999). A different view of naming assumes that lexical access can have two levels but not necessarily two stages (Dell, 1986; Humphreys, Riddoch, & Quinlan, 1988). Therefore, activation of a word during naming involves at least two closely interacting levels, activation of the semantic representation as well as activation of the phonological form of the target word (and perhaps an intermediate, lexeme level). In general, the distinction between these models is significant when distinguishing between types of naming errors shown by participants with aphasia. The implications for these models in terms of semantic treatment have similar consequences as both models can account for the effects of improved word retrieval.

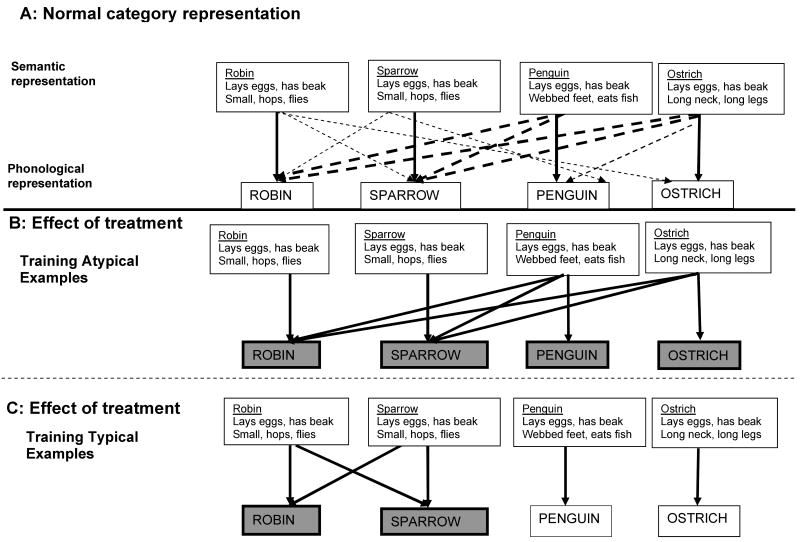

Together with the previously described category structure theories (e.g., Lambon-Ralph et al., 1999; Tyler et al., 2000), the aforementioned lexical access models provide a theoretical framework upon which the effect of typicality as a treatment variable to facilitate lexical access can be constructed. As shown in Figure 2, atypical examples consist of core and distinctive features that carry more weight in their representation within the category. In contrast, typical examples consist of core and prototypical features that carry less weight in their representation within the category. Typicality treatment enhances access to target semantic representations as well as semantically related neighbors which consequently, results in activation of corresponding phonological representations. Because atypical examples (e.g., penguin, ostrich) and their features (e.g., lays eggs, has beak, webbed feet, eats fish, long legs, long neck) exert greater weight than typical examples (represented by bold dashed lines in Figure 2), treatment of atypical examples also reinforces features relevant to more central typical examples (e.g., lays eggs, has beak), thereby facilitating phonological access for those examples as well as shown in Figure 2b. As shown in Figure 2c, because typical examples and their features exert lesser weight, training of these examples only strengthens central semantic features (e.g., lays eggs, has beak, small, hops, flies) and the corresponding typical phonological representations. Consequently, atypical semantic representations (e.g., webbed feet, eats fish, long legs, long neck) remain unaffected and their corresponding phonological representations are not successfully accessed until directly targeted in treatment.

Figure 2.

The semantic complexity hierarchy illustrating semantic and phonological representations within a sample category (bird): (a) atypical examples consist of core and distinctive features (and therefore exert more weight, represented by bold dashed lines) than typical examples which consist of core and shared prototypical features (resulting in less weight, represented by unbold dashed lines). The application of the typicality treatment (b) during treatment of atypical examples, strengthening the features for those examples also reinforces features relevant to more central typical examples, thereby facilitating phonological access for typical examples also (represented by bold solid lines), (c) training atypical features does not exert any weights on the untrained atypical examples. Consequently, access to atypical examples is not facilitated.

Factors Influencing the Effects of Typicality in Treatment

Patient variables influencing treatment outcome

Given these preliminary treatment data, it is worthwhile to discuss various factors that may influence the outcome of this treatment. Some of these factors include age, time post onset of stroke and aphasia subtype (see Table 2). All participants receiving treatment so far have ranged between 47 to 77 years of age, suggesting that clinically relevant recovery trends may indeed be possible even in older participants. This preliminary observation clearly needs to be examined in greater detail. Also, as shown in Table 2, time post the stroke onset does not appear to be a significant predictor of participants' performance thus far. Further, all participants in the Kiran & Thompson study (2003a) were diagnosed with fluent aphasia and concurrent naming, auditory comprehension and semantic processing impairments. For these participants, reinforcing semantic attributes of categories and their examples through both auditory and visual modalities was ostensibly beneficial in facilitating lexical access. In the second study, two additional participants with nonfluent aphasia/apraxia were recruited, who were less responsive to treatment than the three participants with fluent aphasia. Nevertheless, these participants also showed the expected patterns once the treatment protocol was modified to accommodate for errors caused by apraxia.

Stimulus/task specific variables influencing treatment outcome

The treatment effects observed when training atypical or semantically complex items appears to be dependent on at least three stimuli/task specific factors: (a) the typical/atypical stimuli chosen for treatment, (b) the nature of semantic features, and (c) the nature of the protocol followed in treatment. First, the selection of atypical and typical examples for treatment is an important variable in determining treatment outcome. In the above described experiments, several norming procedures were employed to ensure that atypical examples selected were indeed members of that category despite being less representative of the category. Typicality of items was determined based on generation of category exemplars by a group of 20 normal young and elderly participants, followed by collection of average typicality ratings (converted to z scores) for each example in a category by a separate group of 20 normal young and elderly participants. A rating of 1 corresponded to the item being a very good example or fit of the category; a rating of 7 indicated that item was considered a very poor example; a rating of 4 indicated a moderate fit. For treatment, typical examples were selected as the top 10-15 examples with the lowest z scores, whereas atypical examples were chosen as the lowest 10-15 examples with the highest z scores. Moreover, examples selected through this procedure are substantiated by other published norms for typical and atypical examples of categories (Hampton & Gardiner, 1983; Rosch, 1975; Uyeda & Mandler, 1980).

In addition to rated typicality, there are other factors that may influence lexical access. The aforementioned stimuli were also controlled for frequency and familiarity (e.g., kale, escarole are less frequent and familiar) of usage, and homophones (e.g., duck). It may be recalled that typical examples in general, share a number of intercorrelated features (e.g., finch, wren, sparrow share features such as small, hops, chirps, and lives in trees) that can be less distinctive than features of atypical examples. This dimension, while being advantageous in speeding up category verification and feature verification, slows down the lexical access time of individual examples (Kiran & Allison, 2005). This finding is not true of all categories, however; in categories like clothing or vegetables, typical examples are named faster than atypical examples. Hence, an important criterion for selection of typical and atypical examples is that they differ only in their inherent representation of typicality.

A second factor influencing the outcome of typicality treatment is the selection of a diverse set of semantic features that includes both the prototypical features and the distinctive features of the category. In the Kiran and Thompson study (2003a), about 35–40 features were selected that were applicable to at least one example within the category. Of these 8-10 were core features of the category, those that determined category inclusion. The remaining features were distinctive features either more relevant to typical examples or to atypical examples (see Table 1). Semantic features were also controlled for the type of information conveyed. Specifically, equal number of physical (e.g., is red in color, has feathers), functional (e.g., is made into pie, is a predator), characteristic (e.g., is juicy, lays eggs) or contextual attributes (e.g., found in a grocery store, lives near water) were selected. It is notable that these attributes are generally consistent with other normative studies on attribute generation (Barr & Caplan, 1987; Garrard et al., 2001). These carefully selected features were a central component of the typicality treatment, because the main difference between training typical examples and atypical examples involves the variation of semantic features that were manipulated in treatment. As proposed by the complexity account of treatment efficacy (CATE; Thompson et al., 2003), training less semantically complex, typical examples strengthened only the core and shared prototypical features, whereas training more semantically complex atypical examples illustrated the variation of defining, prototypical and distinctive semantic features within the category.

Finally, the protocol employed during treatment likely impacted the treatment effects noted (see Table 3). An important factor influencing the outcome of this treatment, and presumably most treatment approaches, seems to be the extent to which a participant engages in focused semantic processing activities (as shown in Table 3, see processes involved). Therefore, it could be argued that generalization may not be as robust if treatment were focused on traditional cued naming. Regardless of whether participants received treatment for typical or atypical examples, they were exposed to the same set of semantic attributes (N = 30), and were required to select six semantic attributes that were relevant for the target example (See Table 3, step 3). In this process, all participants accepted core features (e.g., lays eggs, has beak). Importantly, when participants were trained on atypical examples (e.g., ostrich), they were required to explicitly process and reject some prototypical features (e.g., flies, lives in trees) while accepting other distinctive features (e.g., long legs, long neck). In contrast, when participants were trained on typical features, they were required to accept prototypical features (e.g., flies, lives in trees) but reject features (e.g., long legs, long neck) associated with atypical examples. In accordance with the semantic complexity hierarchy based on typicality, accepting features relevant to typical examples should be easier and faster than accepting features relevant to atypical examples.

Applications and Extensions of the Semantic Complexity Hypothesis

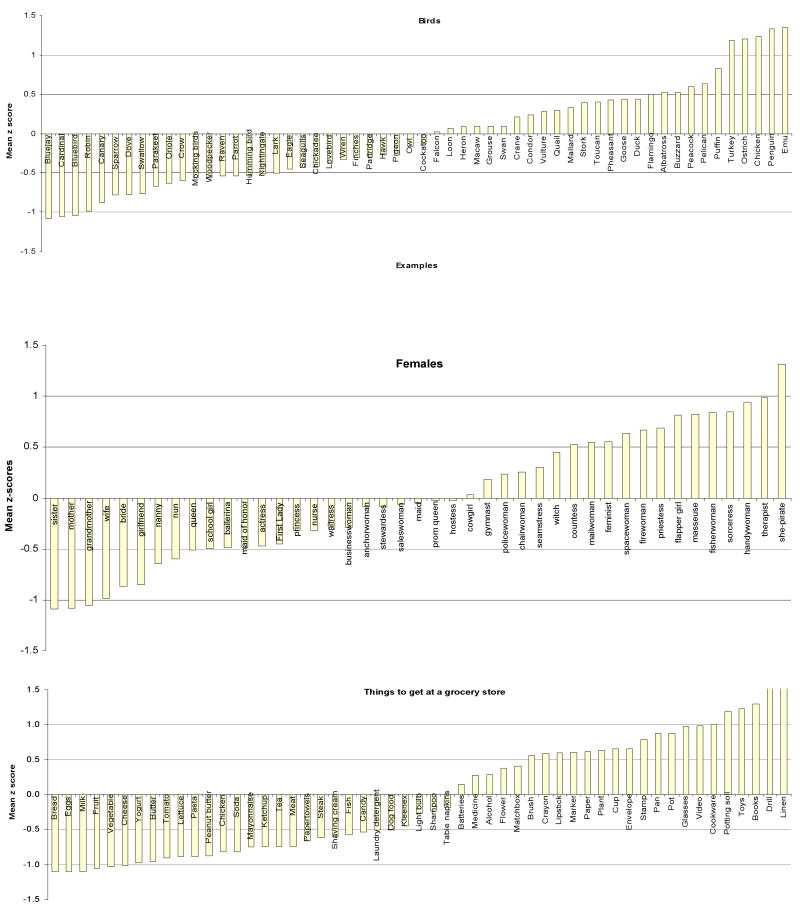

A direct application of the semantic complexity hierarchy involves its realization in treatment of natural categories such as birds and clothing. Typicality is also relevant to other types of categories, including well-defined categories such as female and shapes which have clear definitions and items with equal membership requirements (Armstrong, Gleitman, & Gleitman, 1983). Specifically, mother is considered more typical of the category female than cowgirl, presumably because it is more representative of basic feminine qualities intrinsic to the category female. Further, typicality effects have also been shown in such well-defined categories (e.g., females, shapes, body parts) that are similar to those shown in natural language categories (see Figure 3; Armstrong et al., 1983; Johnson, 2004). Specifically, when frequency and familiarity are controlled, typical examples (e.g., nanny) are named more accurately than atypical examples (e.g., firewoman; Johnson, 2004). Whereas both typical and atypical examples contain core features of the category (e.g., female anatomy), typical examples contain more prototypical attributes (e.g., maternal, protective), and atypical examples contain more distinctive attributes (e.g., requires a special skill; aggressive).

Figure 3.

Typicality ratings for a sample animate category (birds), well defined category (females) and ad hoc category (things to get a grocery store). The mean z score averages are similar for three categories even though the categories are very different in their representation (see text for a detailed discussion).

Typicality hierarchies can also be adapted for more functional stimuli

Specifically, the typicality effect has been demonstrated in ad hoc categories (Barsalou, 1983, 1985; Barsalou & Ross, 1985). Ad hoc categories (or goal derived categories) (e.g., a grocery list) do not have rigid features that constitute category membership; instead, category members follow a loosely combined thread of common features. Although a complexity effect is more difficult to define in such categories, preliminary work in our laboratory has shown that common scripts are also organized in a graded fashion (see Figure 3 for similiarities in typicality ratings between natural language categories such as birds, well-defined categories and adhoc categories). Specifically, typical examples (e.g., bread) are more illustrative of the central goal of the category (e.g., a grocery list) than atypical examples (e.g., table linen). It may be that core features in goal derived categories are restricted to the goal (e.g., can be purchased as a grocery store), but typical examples are still predicted to consist of shared prototypical features (e.g., in the produce section, widest selection available) and atypical examples consist of distinctive features (e.g., seasonal, expensive).

Clinical Relevance

Generalization to naming of untrained items is a constant focus of most treatment studies examining the effectiveness of naming treatments. Indeed, generalization to untrained structures is an essential clinical outcome to successful treatment, particularly in the current healthcare climate that limits the duration of aphasia treatment to a few sessions (Thompson, 2001). Notably, in our treatment study (Kiran & Thompson, 2003a), participants needed fewer sessions to name all items of a category when trained on atypical examples (e.g., participant JH: 8 sessions) compared to typical examples (participant JH: 26 sessions). As noted above, all participants who underwent this treatment also showed changes in their general language processing abilities (measured by improvements on their Aphasia Quotient) following treatment. From the perspective of the individual with aphasia, the ability to retrieve novel items and not just those trained facilitates that individual's return to their normal communicative ability.

Conclusions

This paper has explored the Complexity Account of Treatment Efficacy (CATE; Thompson et al., 2003) in the lexical semantic domain and presented a complexity hierarchy based on typicality. As stated in the introduction, the manifestation of complexity in the semantic domain is less transparent than in syntactic or phonology domains. However, conceptualization of semantic categories as multidimensional vector spaces represented by a network of intercorrelated features allows complexity hierarchies to be developed. Further, although counterintuitive we have demonstrated that complexity impacts recovery of naming in aphasia; that is, training atypical, complex category items results in generalization to simpler typical examples but not vice versa. These findings indicate that the Complexity Account of Treatment Efficacy (CATE; Thompson et al., 2003) can be extended to treatment of lexical semantic deficits by considering the typicality of category items. While this approach to treatment can be potentially applied to most individuals with aphasia presenting with naming deficits, the success of the treatment seemingly relies on the stringent selection of typical/atypical examples and on highlighting the variation of semantic features of the trained category as part of the treatment protocol.

Further research is needed to investigate complexity in the semantic domain. In addition to typicality, other indices of semantic complexity, (e.g., the number of meanings of a particular word), may be equally worthy for translation into treatment hierarchies for naming. To this end, experimental work is required to ascertain normal behavioral correlates of semantic complexity and their effect on language recovery patterns in individuals with aphasia.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr. Cindy Thompson for her valuable input at various stages of this manuscript. The author would also like to thank Jeannette Hoit, Argye Hillis, Mary Boyle and an anonymous reviewer for comments that have strengthened the manuscript. Portions of the work reported here were supported by a grant from NIDCD R03 DC6359 awarded to the author.

References

- Armstrong SL, Gleitman LR, Gleitman H. What some concepts might not be. Cognition. 1983;13:263–308. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(83)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr RA, Caplan LJ. Category representations and their implications for category structure. Memory & Cognition. 1987;15(5):397–418. doi: 10.3758/bf03197730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou L. Ad hoc categories. Memory and Cognition. 1983;11(2):211–227. doi: 10.3758/bf03196968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou L. Ideals, Central tendency, and frequency of instantiation as determinants of graded structure in categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory & Cognition. 1985;11:629–649. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.11.1-4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou L, Ross Daniel R. Contrasting the representation of scripts and categories. Journal of Memory and Language. 1985;24(6):646–665. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M. Semantic feature analysis treatment for anomia in two fluent aphasia syndromes. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology. 2004;13(3):236–249. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2004/025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M, Coehlo C. Application of semantic feature analysis as a treatment for aphasic dysnomia. American Journal of Speech –Language Pathology. 1995;4:94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth B. Lexical access in speech production. In: Marslen Wilson W, editor. Lexical representation and process. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1989. pp. 108–235. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth B. Disorders of phonological encoding. Cognition. 1992;42:261–286. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(92)90045-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramazza A, Hillis A, Rapp B, Romani R. The multiple semantic hypothesis: Mutliple Confusions? Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1990;7:161–189. [Google Scholar]

- Casey PJ. A re-examination of the roles of typicality and category dominance in verifying category membership. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory & Cognition. 1992;18(4):823–34. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.12.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coehlo C, McHugh R, Boyle M. Semantic feature analysis as a treatment for aphasic dysnomia: A replication. Aphasiology. 2000;14:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Davis A, Pring T. Therapy for word finding deficits: more on the effects of semantic and phonological approaches to treatment with anomic patients. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 1991;1:135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Dell GS. A spreading activation theory of retrieval in sentence production. Psychological Review. 1986;92:283–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin JT, Russell RP, Davis MH, Price CJ, Moss HE, Fadili J, Tyler LK. Is there an anatomical basis for category specificity? Semantic memory studies in PET and fMRI. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:54–75. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew RL, Thompson CK. Model based semantic treatment for naming deficits in aphasia. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 1999;42(4):972–990. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4204.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde EM, Humphreys GW. Category specific recognition impairments: A review of important case studies and influential theories. Aphasiology. 1999;13(1):169–193. [Google Scholar]

- Garrard P, Lambon Ralph MA, Hodges J, Patterson K. Prototypicality, distinctiveness and intercorrelation: Analysis of the semantic attributes of living and nonliving concepts. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 2001;18(2):125–174. doi: 10.1080/02643290125857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennari S, Poeppel D. Processing correlates of lexical semantic complexity. Cognition. 2003;89:B 27–B41. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(03)00069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald M, Raymer AM, Richardson ME, Rothi LG. Contrasting treatments for severe impairments of picture naming. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 1995;5:17–49. [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Perecman E, Kellar L, Brown J. Lexical knowledge in anterior and posterior aphasics. Brain and Language. 1980;10:318–330. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(80)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M. The aphasics identification of a superordinate's referents with basic level and subordinate level terms. Cortex. 1980;16:459–469. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(80)80046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M. A bird is a bird: Making references within and without superordinate categories. Brain and Language. 1981;12:313–331. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(81)90022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton JA. Polymorphous concepts in semantic memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal behavior. 1979;18:441–461. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton JA. Prototype models of concept representation. In: Van Mechelen, Hampton JA, Michlanski RS, Theuns P, editors. Categories and Concepts: Theoretical views and inductive data analysis. London, UK: Academic Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton JA. Testing the prototype theory of concepts. Journal of Memory and Language. 1995;34:686–708. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton JA, Gardiner MM. Measures of internal category structure: A correlational analysis of normative data. British Journal of Psychology. 1983;74:491–516. [Google Scholar]

- Hart J, Moo L, Segal J, Adkins E, Kraut M. The neural substrates of semantic memory. In: Hillis A, editor. Handbook of Adult Language Disorders. Taylor and Frances; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Howard D, Patterson K, Franklin S, Orchid-Lisle V, Morton J. The facilitation of picture naming in aphasia. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1985a;2:49–80. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys GW, Riddoch MJ, Quinlan PT. Cascade processes in picture identification. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1988;5:67–103. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L. Typicality effects on naming accuracy in well-defined categories Unpublished masters thesis. University of Texas; Austin: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A. The Western Aphasia Battery. Philadelphia: Grune and Stratton; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Thompson CK. The role of semantic complexity in treatment of naming deficits: training semantic categories in fluent aphasia by controlling examplar typicality. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2003a;46(4):773–87. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/061). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Thompson CK. Effect of typicality on online category verification of animate category exemplars in aphasia. Brain and Language. 2003b;85:441–450. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(03)00064-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Ntourou K, Eubank M. Effects of typicality on category verification in inanimate categories in aphasia. Manuscript submitted for publication 2005a [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Ntourou K, Eubank M, Shamapant S. Typicality of inanimate category exemplars in aphasia: Further evidence for the semantic complexity effect. Brain and Language. 2005b;95:178–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Allison K. Effect of typicality on lexical processing of feature based and perceptually based categories. Manuscript submitted for publication 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu LK. Recent views of conceptual structure. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(3):500–526. [Google Scholar]

- Lambon-Ralph MA, Patterson K, Hodges JR. The relationship between naming and semantic knowledge for different categories in dementia of Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35(9):1251–1261. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larochelle S, Pineu H. Determinants of response time in the semantic verification task. Journal of Memory and Language. 1994;33:796–823. [Google Scholar]

- Levelt WJM. Speaking: From intention to articulation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Levelt WJ, Roelofs A, Meyer AS. A theory of lexical access in speech production. Brain and Behavioral Sciences. 1999;22:1–75. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99001776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell S, Beeson PM, Holland AL. The efficacy of semantic cueing procedure on naming performance of adults with aphasia. American Journal of Speech –Language Pathology. 1995;4(4):109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Maher LM, Raymer AM. Management of anomia. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2004;11(1):10–21. doi: 10.1310/318R-RMD5-055J-PQ40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J, Robson J, Pring T, Chiat S. Why does monitoring fail in jargon aphasia: Comprehension, judgment and therapy evidence. Brain and Language. 1998a;63 doi: 10.1006/brln.1997.1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JC, Pound C, White-Thompson M, Pring T. The use of picture matching tasks to assist in word retrieval in aphasic patients. Aphasiology. 1990;4(2):167–184. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Rae K, de Sa VR, Seidenberg MS. On the nature and scope of featural representations in word meaning. Journal of Experimental Psychology General. 1997;126:99–130. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.126.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey ME, Glucksberg S. Natural categories. Well defined or fuzzy sets? Memory & Cognition. 1978;6:462–472. [Google Scholar]

- Mervis CB, Catlin J, Rosch E. Relationships among goodness of example, category norms, and word frequency. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 1976;7:283–284. [Google Scholar]

- Moore CJ, Price CJ. A functional neuroimaging study of the variables that generate category specific processing object differences. Brain. 1999;122:943–962. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.5.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickels L. Therapy for naming disorders: Revisiting, revising and reviewing. Aphasiology. 2002;16(1011):935–979. [Google Scholar]

- Nickels L, Best W. Therapy for naming disorders (Part I): principles, puzzles and progresses. Aphasiology. 1996a;10(1):21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Plaut DC. Relearning after damage in connectionists networks: Toward a theory of rehabilitation. Brain and Language. 1996;52:25–82. doi: 10.1006/brln.1996.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Keele SW. On the genesis of abstract ideas. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1968;77:353–363. doi: 10.1037/h0025953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pring T, Hamilton A, Harwood A, McBride L. Generalization of naming after picture/word matching tasks: only items appearing in therapy benefit. Aphasiology. 1993;7(4):383–394. [Google Scholar]

- Rips LJ, Shoben EJ, Smith EE. Semantic distance and the verification of semantic distance. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1973;12:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rosch E. On the internal structure of perceptual and semantic categories. In: Moore TE, editor. Cognitive development and the acquisition of language. New York: Academic Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Rosch E. Cognitive representation of semantic categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1975;104:192–233. [Google Scholar]

- Rosch E, Mervis C. Family resemblances: Studies in the internal structure of categories. Cognitive Psychology. 1975;7:573–604. [Google Scholar]

- Saffran E, Scwartz M. Of cabbages and things: Semantic memory from a neuropsychological perspective. In: Meyer D, Cornblum S, editors. International Symposium on Attention and Performance. XV. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sartori G, Lombardi L. Semantic Relevance and semantic disorders. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16(3):439–442. doi: 10.1162/089892904322926773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EE, Shoben EJ, Rips LJ. Structure and process in semantic memory: A featural model of semantic association. Psychological Review. 1974;81:214–241. [Google Scholar]

- Storms G, De Boek P, Ruts W. Prototype and exemplar based information in natural language categories. Journal of Memory and Language. 2000;42:51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CK. Treatment of underlying forms. In: Chapey R, editor. Language Intervention and Strategies in Aphasia and Related Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Fourth. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 605–626. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CK, Shapiro LP, Kiran S, Sobecks J. The role of syntactic complexity in treatment of sentence deficits in agrammatic aphasia: The complexity account of treatment effects (CATE) Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2003;46:607. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/047). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler LK, Durrant-Peatfield MR, Levy JP, Voice JK, Moss HE. Distinctiveness and correlations in the structure of categories- behavioural data and connectionist model. Brain and Language. 1996;55:89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler LK, Moss HE, Durrant-Peatfield MR, Levy JP. Conceptual structure and the structure of concepts: A distributed account of category specific deficits. Brain and Language. 2000;75:195–231. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler LK, Moss HE. Towards a distributed account of conceptual knowledge. Trends Cogn Sci. 2001;5(6):244–252. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01651-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyeda KM, Mandler F. Prototypicality norms for 28 semantic categories. Behavior Research Methods and Instrumentation. 1980;12(6):587–595. [Google Scholar]