Abstract

We report a rare case of duodenal perforation caused by an ingested 12-cm long toothbrush handle. A 22-year-old female presented with intermittent epigastric pain for 6 d after swallowing a broken toothbrush. The swallowed toothbrush could not be removed from the second portion of the duodenum by endoscopy. Laparotomy revealed a perforation in the anterior wall of the duodenal bulb. The toothbrush was removed via the perforation which was debrided and closed. There were no postoperative complications.

Keywords: Duodenum, Endoscopy, Laparotomy, Perforation, Toothbrush

INTRODUCTION

Ingestion of various types of foreign bodies, such as toothpicks, fish or meat bones, screws, coins, metal clips, teeth, dental prosthesis, and spoon handles, has been reported[1–3]. Most ingested foreign bodies pass through the gastrointestinal tract spontaneously without causing untoward effects. However, sometimes these foreign bodies cause obstruction or perforation of the gastrointestinal tract necessitating surgical intervention[2–5]. Here, we report a rare case of duodenal perforation resulting from an ingested toothbrush.

CASE REPORT

A 22-year-old female presented with intermittent epigastric pain for 6 d. Eight days prior to hospitalization, she experienced nausea and foreign body sensation in the throat. She attempted to induce vomiting by irritating the pharynx with the distal end of a toothbrush handle. The toothbrush broke at the junction of the handle and the brush head. Unfortunately, she accidentally swallowed the handle of the broken toothbrush, which was 12 cm long. She had no passage of tarry noted after swallowing the foreign body. However, she experienced epigastralgia 2 d after ingesting the toothbrush. Endoscopy was performed twice at another hospital. However, the swallowed toothbrush could not be removed. The patient denied any history of excessive alcohol consumption or illicit drug use. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

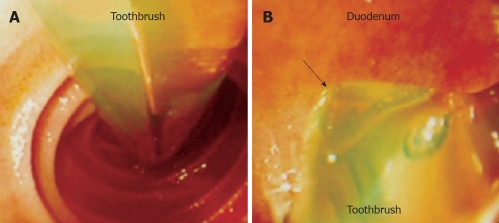

Upon admission, the patient was afebrile, and her vital signs were normal. Mild tenderness but no rebound pain was noted in the upper abdomen. Laboratory values were as follows: 10.0 g/dL hemoglobin, 30.5% hematocrit, 7100/mm3 white blood cells (WBC), 30 U/L aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 32 U/L alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and 72 U/L alkaline phosphatase. Chest and plain abdominal X-ray examinations were unremarkable. Endoscopic examination revealed a broken toothbrush handle in the second portion of the duodenum (Figure 1A). The blunt end of the toothbrush faced distally and the broken end, proximally against the duodenal wall (Figure 1B). There was an ulcer on the anterior wall of the duodenal bulb. Endoscopic removal of the toothbrush was reattempted but failed.

Figure 1.

A toothbrush handle found in the second portion of the duodenum (A) and the pointed broken end (arrow) of the toothbrush handle impinged on the wall of the duodenal bulb (B).

Surgery was performed on the second day of hospitalization. Laparotomy revealed a perforation in the anterior wall of the first portion of the duodenum. The perforation had necrotic edges and was sealed off by the infundibulum of the gallbladder. The toothbrush was removed through this perforation which was debrided and then closed primarily with interrupted silk sutures reinforced with an omental patch. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful. The patient resumed oral intake on the fourth postoperative day and was discharged from the hospital 7 d after surgery.

DISCUSSION

Several factors are associated with the ingestion of foreign bodies. Children usually swallow foreign bodies because of carelessness. In adults, poor vision, mental disease, drug addiction, wearing of dentures, and rapid eating have been implicated as the etiologic factors of foreign body ingestion[2–5]. In addition, excessive alcohol intake and extremely cold fluids may dull the sensitivity of the palatal surface and increase the risk of swallowing foreign bodies[6]. The majority of ingested foreign bodies pass uneventfully through the gastrointestinal tract[2–5]. However, in some patients, the ingested foreign body may cause impaction, perforation, or obstruction. Perforation of the gastrointestinal tract may be associated with a considerably high mortality and morbidity. Gastrointestinal tract perforation may cause peritonitis, abscess formation, inflammatory mass formation, obstruction, fistulae, and hemorrhage[2,6]. In addition, foreign body perforation of the gastrointestinal tract may involve adjacent structures such as the kidneys, psoas muscle, and inferior vena cava[7,8]. Rare cases of foreign body migration to the pleura, heart, kidneys, or liver have been reported[9–12]. Most deaths in patients with foreign body perforation of the gastrointestinal tract are due to fulminant sepsis[2,13,14]. Therefore, efforts should be made to remove the ingested foreign bodies if they cannot pass through the gastrointestinal tract spontaneously.

In this case, the broken toothbrush handle was entrapped in the duodenal sweep and resulted in perforation of the duodenum. Intestinal injury resulting from an ingested foreign body tends to occur in areas of acute angulation but it may occur in all segments of the gastrointestinal tract[6]. The retroperitoneal, relatively immobile, and rigid nature of the duodenum as well as its deep transverse rugae and sharp angulations make it a common site for the entrapment of long and sharp-ended objects. Furthermore, the properties of foreign bodies determine the degree of complications caused by them. Thin and sharp foreign bodies such as chicken and fish bones, toothpicks, and straightened paperclips carry a higher risk of perforation. Long, slender, sharp-ended items have difficulty in traversing the tortuous gastrointestinal tract[2,3]. In a review of 31 cases of toothbrush ingestion, no episodes of spontaneous passage were reported[15]. Complications related to pressure necrosis, including gastritis, mucosal tears, and perforations, occurred in several of these cases.

Although a conservative approach toward foreign body ingestion is justified, early endoscopic removal of the ingested foreign body from the stomach is recommended[2,4,15]. Ertan et al[16] reported the first case of successful removal of a swallowed toothbrush. Other authors found the endoscopic approach unsuccessful due to the size and shape of the ingested toothbrush[17,18]. Esophageal perforation during the endoscopic extraction of a toothbrush has been reported[6]. In addition, objects longer than 6-10 cm have difficulty in passing the duodenal sweep[19]. Therefore, in cases of unsuccessful removal of gastric foreign bodies that are longer than 6.0 cm, surgical removal of them should be considered. Wishner and Rogers[18] reported a case of successful laparoscopic removal of a toothbrush from the stomach. Laparotomy in this case is justified because it is difficult to remove a toothbrush from the duodenum via a laparoscopic approach.

In conclusion, an ingested toothbrush cannot pass spontaneously through the gastrointestinal tract. Early removal of the ingested toothbrush is advised to avoid impaction of the toothbrush at the duodenum and to minimize morbidity. Endoscopic removal should be performed by a skilled endoscopist. If this is not possible or unsuccessful, a surgical approach is recommended.

Peer reviewer: Manfred V Singer, Professor, Department of Medicine II, University Hospital at Mannheim, Theodor- Kutzer-Ufer 1-3, Mannheim 68167, Germany

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.McCanse DE, Kurchin A, Hinshaw JR. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies. Am J Surg. 1981;142:335–337. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(81)90342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velitchkov NG, Grigorov GI, Losanoff JE, Kjossev KT. Ingested foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract: retrospective analysis of 542 cases. World J Surg. 1996;20:1001–1005. doi: 10.1007/s002689900152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webb WA. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: update. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:39–51. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosca S, Manes G, Martino R, Amitrano L, Bottino V, Bove A, Camera A, De Nucci C, Di Costanzo G, Guardascione M, et al. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: report on a series of 414 adult patients. Endoscopy. 2001;33:692–696. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ginsberg GG. Management of ingested foreign objects and food bolus impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:33–38. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selivanov V, Sheldon GF, Cello JP, Crass RA. Management of foreign body ingestion. Ann Surg. 1984;199:187–191. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198402000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Justiniani FR, Wigoda L, Ortega RS. Duodenocaval fistula due to toothpick perforation. JAMA. 1974;227:788–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nigri GR, Di Giulio E, Di Nardo R, Pezzoli F, D'Angelo F, Aurello P, Ravaioli M, Ramacciato G. Duodenal perforation and right hydronephrosis due to toothpick ingestion. J Emerg Med. 2008;34:55–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloch DB. Venturesome toothpick. A continuing source of pyogenic hepatic abscess. JAMA. 1984;252:797–798. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyns BP, Faveere BC, Van de Werf FJ, Dotremont G, Daenen WJ. Constrictive pericarditis due to ingestion of a toothpick. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57:489–490. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)91031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaffer RD. Subcutaneous emphysema of the leg secondary to toothpick ingestion. Arch Surg. 1969;99:542–545. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1969.01340160122029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jenson AB, Fred HL. Toothpick pleurisy. JAMA. 1968;203:988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budnick LD. Toothpick-related injuries in the United States, 1979 through 1982. JAMA. 1984;252:796–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bee DM, Citron M, Vannix RS, Gunnell JC, Bridi G, Juston G Jr, Kon DV. Delayed death from ingestion of a toothpick. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:673. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903093201019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirk AD, Bowers BA, Moylan JA, Meyers WC. Toothbrush swallowing. Arch Surg. 1988;123:382–384. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400270122020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ertan A, Kedia SM, Agrawal NM, Akdamar K. Endoscopic removal of a toothbrush. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:144–145. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(83)72564-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilcox DT, Karamanoukian HL, Glick PL. Toothbrush ingestion by bulimics may require laparotomy. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1596. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wishner JD, Rogers AM. Laparoscopic removal of a swallowed toothbrush. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:472–473. doi: 10.1007/s004649900393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisen GM, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, Faigel DO, Goldstein JL, Johanson JF, Mallery JS, Raddawi HM, Vargo JJ 2nd, Waring JP, et al. Guideline for the management of ingested foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:802–806. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]