Abstract

Pylephlebitis, a rare complication of acute appendicitis, is defined as thrombophlebitis of the portal venous system. Pylephlebitis usually occurs due to secondary infection in the region drained into the portal system. We report a case of pylephlebitis caused by acute appendicitis. The patient was transferred from a private clinic 1 wk after appendectomy with the chief complaints of high fever and abdominal pain. He was diagnosed with pylephlebitis of the portal vein and superior mesenteric vein by CT-scan. The patient was treated with antibiotics and anticoagulation therapy, and discharged on the 25th day and follow-up CT scan showed a cavernous transformation of portal thrombosis.

Keywords: Acute appendicitis, Pylephlebitis, Antibiotics, Anti-coagulation therapy

INTRODUCTION

Pylephlebitis is defined as thrombophlebitis of the portal venous system associated with intraperitoneal septic conditions, such as colonic diverticulitis, acute appendicitis, and cholangitis. Pylephlebitis is considered a seriously lethal condition.

Recent advances in antibiotic therapy have made the occurrence of pylephlebitis very rare. However, the mortality rate remains high because non-specific symptoms and low index of suspicion usually delay the diagnosis of pylephlebitis. The early use of optimal diagnostic modalities and surgical interventions are essential to ensure the survival of patients.

We describe a case of thrombophlebitis of the portal vein and superior mesenteric vein as a complication of acute appendicitis, which was successfully treated with antibiotics and anticoagulation therapy.

CASE REPORT

A 26-year-old man was transferred to the emergency department with the complaints of high fever and severe abdominal pain for 4 d. He underwent appendectomy for acute appendicitis 1 wk earlier. During the hospital stay, he had persistent fever up to 40°C and diarrhea, and was treated with antibiotics, fluids and anti-pyretics.

On arrival, he had an elevated temperature of 39.7°C and complained of severe epigastric pain. His blood pressure was 140/80 mmHg, his pulse rate was 114/min, and the respiration rate was 24/min. Physical examination noted epigastric pain and tenderness, but could not find rebound tenderness and muscle guarding. Laboratory results showed mild leukocytosis (11500/mm3), anemia (9.9 g/dL hemoglobin), and elevated bilirubin (1.6/0.9 mg/dL total/direct bilirubin), alkaline phosphatase (213 U/L), and γ-GT (73 U/L).

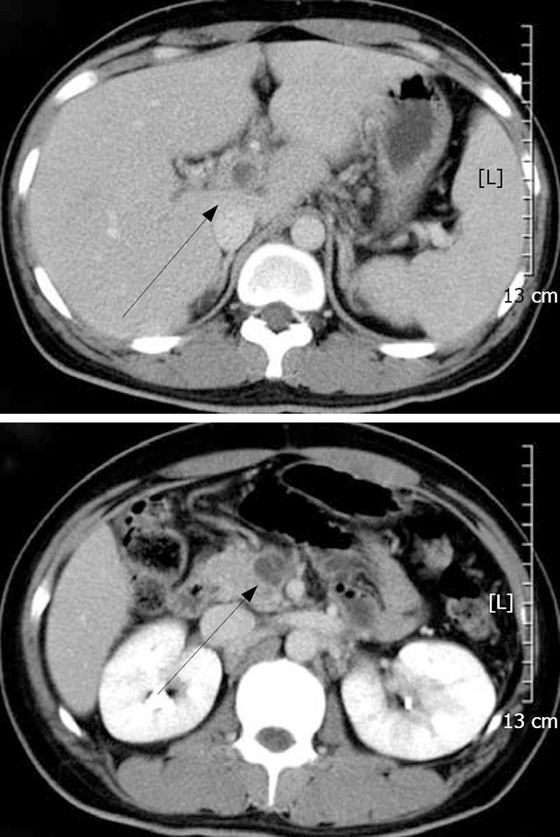

Abdominal CT scan demonstrated thrombus formation in the portal vein extending from the superior mesenteric vein (SMV; Figure 1). He was admitted to the intensive care unit and treated with systemic IV antibiotics (the 3rd generation cephalosporin and metronidazole, chosen by empirical therapy) and anticoagulation therapy (a subcutaneous injection of low molecular heparin, 1 mg/kg every 12 h). He was given nothing by mouth and parenteral nutrition was initiated to decrease the portal blood flow from the mesenteric vein.

Figure 1.

CT scan showing total occlusion of the portal vein with a thrombus (arrow) extending to the superior mesenteric vein.

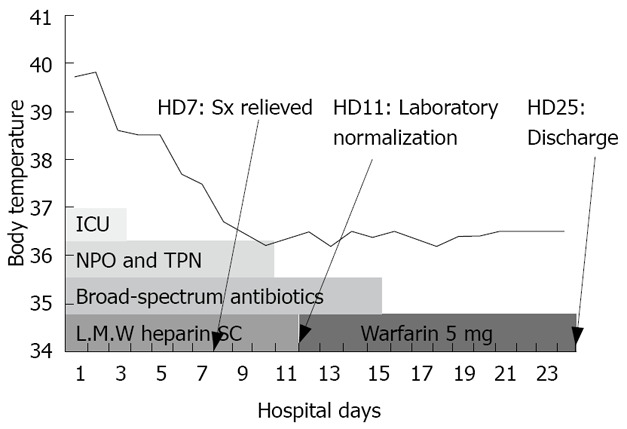

By the 3rd hospital day, his symptoms were gradually improved and the liver dysfunction and leukocytosis were normalized on the 11th day. Thereafter, oral feeding was started. No microorganisms were identified in his blood culture specimen. On the 12th hospital day, low molecular heparin was replaced with warfarin (5 mg/d) and continued until one month after discharge (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinical progress and treatment course of the patient. ICU: Intensive care unit; NPO: Non per os; TPN: Total parenteral nutrition; HD: Hospital day; L.M.W. heparin SC: Low molecular weight heparin subcutaneous injection.

The follow-up CT scan taken 2 wk after admission showed a cavernous transformation of portal vein thrombus and improved SMV thrombosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Arrow indicates the cavernous transformation of the portal vein on follow-up CT scan.

The patient was discharged on the 25th day without complications. A follow-up CT scan after 6 mo showed a slightly increased cavernous transformation of the portal vein and marked improvement of the SMV thrombosis. He appeared healthy and had no clinical and laboratory abnormalities on follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Although pylephlebitis is a rare complication derived from septic conditions of the portal drainage area most commonly caused by colonic diverticulitis, it occurs in association with acute appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease, suppurative pancreatitis, acute cholangitis, bowel perforation, and pelvic infection[1–3].

This disease entity occurred in 0.4% of patients with acute appendicitis before 1950, but it has become very rare due to major advances in antibiotic therapy and surgical treatment[4]. However, the reported mortality rate of pylephlebitis is 30%-50%, partly due to a delay in diagnosis from its atypical clinical findings and a low index of suspicion[1,5].

Reported cases of pylephlebitis are mainly young children, with a mortality rate of up to 50%[4,6–8]. Children are particularly at a great risk of appendiceal perforation because the diagnosis is delayed. As a result, young children are prone to develop pylephlebitis.

The clinical features of pylephlebitis are non-specific. High fever, chills, malaise, right upper quadrant pain, and tenderness are the initial clinical manifestations. Balthazar and Gollapudi[9] reported that only 30% of patients with pylephlebitis present with localizing clinical signs of a primary source of sepsis. Laboratory findings, such as leucocytosis and mild abnormalities of liver function tests, are usually non-specific, but jaundice is rare except in case of multiple liver abscesses[4,5,7,10]. Our patient was treated conservatively for epigastric pain, high fever, and diarrhea after appendectomy in a private clinic, as there was no suspicion of pylephlebitis.

Blood cultures revealed no microorganisms in our case. Baril et al[5] reported that bacteremia is present in less than one-half of patients, whereas Balthazar and Gollapudi[9] reported that up to 80% of patients have positive blood cultures, and Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterobacter spp. are the most common microorganisms isolated[4,7,9,10].

Modern diagnostic imaging techniques help the early diagnosis of acute phase pylephlebitis. The sensitivity and specificity of CT scans for pylephlebitis are not known. However, CT scans could simultaneously detect the primary source of infection, extent of pylephlebitis, and intrahepatic abnormalities, such as liver abscesses. Thus, CT scan is the most reliable initial diagnostic choice[9–11]. Air bubbles or thrombi of the portal venous system are the critical CT findings of pylephlebitis[9]. Ultrasound scan with color flow Doppler is also a sensitive test for confirming partial patency of the portal vein and portal vein thrombosis[7].

Once a diagnosis of pylephlebitis is established, appropriate treatment should be initiated as soon as possible.

The principal of treatment for pylephlebitis is to remove the source of infection and eradicate the toxic microorganisms using appropriate antibiotics. Immediate surgical intervention is necessary in most cases, but Stitzenberg et al[8] reported that interval laparoscopic appendectomy can be performed 3 mo after treatment with antibiotics and anticoagulants. Regarding the treatment of portal thrombosis, Nishimori et al[11] reported that surgical thrombectomy can be performed through the ileocolic vein using a Fogarty catheter, but most reported cases are treated with systemic antibiotics and anticoagulants. A minimum of 4 wk of antibiotic therapy is usually recommended and patients presenting with a hepatic abscess should receive at least 6 wk of antibiotic therapy[7,10].

The effectiveness of anticoagulants in the treatment of pylephlebitis is still controversial. We administered low molecular heparin for 11 d initially and warfarin for 1.5 mo. Condat et al[12] recommended early anticoagulants therapy because the recanalization of the portal system was significantly higher in the anticoagulation group compared to the control group. Baril et al[5] insisted that anticoagulants should be considered carefully because complications could present in 20% of patients, and it is not necessary in patients with thrombus isolated to the portal vein, but could be used for prevention of intestinal ischemia in patients with involvement of the superior or inferior mesenteric vein. Lim et al[10] recommended anticoagulation for the prevention of septic pulmonary embolism from infected portal thrombi.

In summary, pylephlebitis is a rare, but fatal complication of acute appendicitis. Therefore, when pylephlebitis is suspected, immediate CT scan and antibiotic therapy, with or without surgical intervention, should be started to ensure the survival of patients.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Mercedes Susan Mandell, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Leprino Office Building, 12401 E. 17th Ave, B113, Aurora 80045, United States

S- Editor Zhong XY L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Yin DH

References

- 1.Plemmons RM, Dooley DP, Longfield RN. Septic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein (pylephlebitis): diagnosis and management in the modern era. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1114–1120. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.5.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuliano CT, Zerykier A, Haller JO, Wood BP. Radiological case of the month. Pylephlebitis secondary to unsuspected appendiceal rupture. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143:1099–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baddley JW, Singh D, Correa P, Persich NJ. Crohn's disease presenting as septic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein (pylephlebitis): case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:847–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang TN, Tang L, Keller K, Harrison MR, Farmer DL, Albanese CT. Pylephlebitis, portal-mesenteric thrombosis, and multiple liver abscesses owing to perforated appendicitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:E19. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.26401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baril N, Wren S, Radin R, Ralls P, Stain S. The role of anticoagulation in pylephlebitis. Am J Surg. 1996;172:449–452; discussion 452-453. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slovis TL, Haller JO, Cohen HL, Berdon WE, Watts FB Jr. Complicated appendiceal inflammatory disease in children: pylephlebitis and liver abscess. Radiology. 1989;171:823–825. doi: 10.1148/radiology.171.3.2655006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vanamo K, Kiekara O. Pylephlebitis after appendicitis in a child. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1574–1576. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.27052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stitzenberg KB, Piehl MD, Monahan PE, Phillips JD. Interval laparoscopic appendectomy for appendicitis complicated by pylephlebitis. JSLS. 2006;10:108–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balthazar EJ, Gollapudi P. Septic thrombophlebitis of the mesenteric and portal veins: CT imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:755–760. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200009000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim HE, Cheong HJ, Woo HJ, Kim WJ, Kim MJ, Lee CH, Park SC. Pylephlebitis associated with appendicitis. Korean J Intern Med. 1999;14:73–76. doi: 10.3904/kjim.1999.14.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishimori H, Ezoe E, Ura H, Imaizumi H, Meguro M, Furuhata T, Katsuramaki T, Hata F, Yasoshima T, Hirata K, et al. Septic thrombophlebitis of the portal and superior mesenteric veins as a complication of appendicitis: report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34:173–176. doi: 10.1007/s00595-003-2654-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Condat B, Pessione F, Helene Denninger M, Hillaire S, Valla D. Recent portal or mesenteric venous thrombosis: increased recognition and frequent recanalization on anticoagulant therapy. Hepatology. 2000;32:466–470. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.16597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]