ABSTRACT

Objective: We report cases of central or atypical skull base osteomyelitis and review issues related to the diagnosis and treatment. Methods: The four cases presented, which were drawn from the Oxford, United Kingdom, skull base pathology database, had a diagnosis of central skull base osteomyelitis. Results: Four cases are presented in which central skull base osteomyelitis was diagnosed. Contrary to malignant otitis externa, our cases were not preceded by immediate external infections and had normal external ear examinations. They presented with headache and a variety of cranial neuropathies. Imaging demonstrated bone destruction, and subsequent microbiological analysis diagnosed infection and prompted prolonged antibiotic treatment. Conclusion: We concluded that in the diabetic or immunocompromised patient, a scenario of headache, cranial neuropathy, and bony destruction on imaging should raise the possibility of skull base osteomyelitis, even in the absence of an obvious infective source. The primary goal should still be to exclude an underlying malignant cause.

Keywords: Skull base, osteomyelitis, cranial neuropathies, otitis externa

Skull base osteomyelitis (SBO) is a serious, life-threatening condition seen most commonly in elderly diabetic or immunocompromised patients. Usually, it is a complication of otitis externa when repeated episodes fail to resolve with topical medications and aural toilet. Pain may become worse, granulation tissue is seen within the auditory canal, the bone of the external auditory canal becomes involved, and cranial neuropathies may arise. This malignant otitis externa (MOE) can be difficult to treat, but it is a reasonably well recognized clinical entity that should be a straightforward diagnosis in the ears, nose, and throat (ENT) setting. The terminology for the condition is varied, and MOE is also referred to as necrotizing otitis externa as well as SBO.

However, this is not the only pattern of presentation for SBO. Although the patient population most at risk remains the same, an initial history of otitis externa is not always apparent. Whereas MOE primarily affects the temporal bone, central or atypical SBO can be seen affecting the sphenoid and occipital bone, often centered on the clivus, and can be considered a variant of MOE. It can present with headache and a variety of cranial neuropathies, often a combination of VI and lower cranial nerve (CN) neuropathies. The imaging findings are of particular concern because they frequently mimic malignancy, which makes accurate histological diagnosis all the more important. However, once diagnosed and treated with appropriate antibiotics, it is one of the few times when CN palsies can be seen to resolve. The greatest challenge, however, remains in differentiating SBO from skull base malignancy.

METHODS

The Department of Otolaryngology at the John Radcliffe Hospital is the regional tertiary referral center for skull base pathology. It is managed in a multidisciplinary way with, among others, neurosurgeons, neuroradiologists, infectious disease/microbiologists, oncologists, speech and language therapists, and dieticians. A database is kept of all patients seen with skull base pathology (any pathology involving the cranial base), irrespective of how the patient is subsequently managed. It was from this database that the cases discussed here were identified.

Inclusion criteria were cases of skull base bony infection, as suggested by radiological, histological, and microbiological findings, where there was no immediate temporal relationship to a case of otitis externa.

A review of the (MEDLINE, searching 1950 to June 2008) made for other case reports of central or atypical skull base osteomyelitis. Cases that had a clear temporal relationship to an ear infection were excluded because these were assumed to fall under the category of more typical SBO or MOE.

Case 1

A 74-year-old type II diabetic man presented with a 2-month history of progressive dysphagia, weight loss, and breathy voice. Flexible nasoendoscopy revealed left vocal cord palsy and pooling of saliva in the pyriform fossae. Neurological assessment revealed reduced elevation of the right soft palate, fasciculation of the left side of the tongue, wasted right side of the tongue, and weak left sternocleidomastoid muscle action. Bilateral CN palsies were present (left, X, XI; right, IX, X, XII). Ear examination was unremarkable and the patient had no preceding history of otitis externa. Blood tests demonstrated a raised white cell count (WCC) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Panendoscopy was unremarkable. While on barium swallow, the patient was unable to coordinate swallowing, and aspiration was demonstrated.

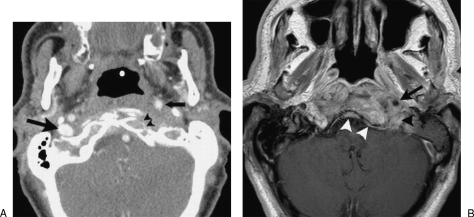

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1A) demonstrated cortical bone erosion of the left side of the clivus and left occipital condyle as well as occlusion of the left internal jugular vein and anterior displacement of the left internal carotid artery just below the skull base. There was opacification of the left middle ear and mastoid air cells but no evidence of bone erosion of the external ear canal. A subsequent gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the skull base (Fig. 1B) showed diffuse soft tissue swelling and pathological contrast enhancement in the prevertebral and carotid space below the skull base, in continuity with pathological enhancement of bone marrow in the central skull base, including the basiocciput, left occipital condyle, and left petrous apex. Thickening and enhancement of the dura in the region of the clivus was also evident. On the basis of the imaging findings, it was not possible to distinguish with certainty between a neoplastic and an infectious process.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the skull base (A) shows erosion of the anterior cortex of the left occipital condyle (arrowheads) as well as anterior displacement of the left internal carotid artery (small arrow). The right internal jugular vein is normal (large arrow), whereas the left internal jugular vein is completely occluded. Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the skull base (B) shows pathological contrast enhancement in the clivus extending into the soft tissues surrounding the left internal carotid artery (arrow) and jugular foramen (black arrowhead). There is thickening and enhancement of the clival dura (white arrowheads).

A subsequent chest infection (bibasal pneumonia) was thought likely to be due to aspiration. Antibiotic treatment saw a temporary improvement in the WCC and CRP that rose again once the chest infection had resolved. Diabetic control proved difficult, requiring use of an insulin sliding scale, although oral intake continued to improve as CN palsy compensation was observed.

An initial examination under anesthesia (EUA) and transnasal endoscopic biopsy of the clivus showed histological features consistent with an infective or inflammatory process only, and no dysplastic or malignant cells. Microbiology grew Pseudomonas species and Entamoeba coli. Sensitivities were established, and 1 month of intravenous meropenem was prescribed. One month after the initial admission, a left VI nerve palsy presented as diplopia. A repeat MRI suggested that this was due to inflammatory tissue at the petrous apex/cavernous sinus. By this stage, CNs IX and X showed some improvement with good and symmetrical palatal elevation and increased sternocleidomastoid muscle strength and tongue movements (fasciculations were gone). Also, XI and XII functions were improving. Left recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy remained, although the voice was improved by compensation from the contralateral cord. After 1 week of meropenem, the WCC and CRP had normalized; clinically, the patient had improved but was continued on oral antibiotic therapy for several months.

Case 2

A 79-year-old immunosuppressed man was referred from Neurology with a 3-month history of headache, several weeks of hoarse voice, dysphagia, and 1 week of diplopia on looking to the left. He had recently completed chemotherapy for bladder cancer. Cranial nerve palsies were left-sided VI, IX, X, and possible early XII. He also had reduced corneal reflex yet normal facial sensation. Ear canal examination was normal, although middle ear effusion was noted. There was no preceding history of otitis externa.

A CT scan showed a soft tissue mass at the left skull base, adjacent to the petrous apex of the temporal bone and involving the jugular foramen on its medial aspect with bony destruction. The lesion was thought to represent a malignant process; however, antibiotics were commenced in the hope they would help if it were an infective process. Biopsy was taken from abnormal tissue found at the jugular bulb. Frozen section at the time of surgery suggested a highly cellular tumor, but without forming a particular pattern and with some suboptimal appearance due to processing problems. Some areas had a dense acute inflammatory infiltrate. Although subsequent histological analysis failed to show any evidence of tumor, microbiology grew Pseudomonas species; therefore, appropriate treatment for this was started. A supplementary pathology report concluded that the appearances were consistent with an inflammatory lesion with a dense fibrous component. Swallowing improved back to near normal over a period of months. Parenteral antibiotic treatment continued for 9 months. The patient's raised CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were both seen to normalize over the course of treatment.

Case 3

An 82-year-old, non–insulin-dependent diabetic man presented with left XII and VI CN palsies. Further questioning revealed a prolonged period of prior treatment to control an episode of otitis externa on the same side ~4 months earlier, although this had apparently been successful and the patient was symptom-free in the interim. The ear examination was normal at presentation. A CT scan that had been performed during the course of the otitis externa failed to demonstrate any bony erosion or evidence of malignant otitis externa.

Further imaging was arranged on his admission, and a destructive lesion with bony erosion was noted at the skull base on CT. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed an extensive soft tissue lesion occupying the infratemporal fossa bilaterally and erosion of the occipital bone at the left anterior margin of the foramen magnum extending toward the petrous apex on that side, which enhanced with contrast. This was considered to represent a primary malignant process; however, a metastatic malignancy or inflammatory disorder such as osteomyelitis of the skull base could not be excluded. Parenteral antibiotic treatment was started, and it resolved the temperature and improved the inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP) that had been raised.

Analysis of an endoscopic transnasal biopsy of the clivus (via the sphenoid) showed a diffuse inflammatory infiltrate, but no evidence of malignancy. Microbiology analysis demonstrated a coagulase negative Staphylococcus. Antibiotic therapy was adjusted because initially antipseudomonal treatment had been used. After several months of treatment, CN function improved to near normal. Antibiotics were continued for 6 months. Follow-up serial MRI showed resolution.

Case 4

A 68-year-old nondiabetic man presented with increasing headache and left XII palsy. He developed subsequent transient ischemic attacks and left Horner's syndrome; VII and X palsies also developed. Again, a past history of a prolonged period of otitis externa was recorded that had been successfully treated several months earlier, with a normal ear examination on presentation.

Computed tomography scanning demonstrated a mass in the medial part of the temporal bone and skull base eroding into the clivus. Middle ear and mastoid findings on the left were felt to be in keeping with eustachian tube obstruction rather than a primary disease process of the middle ear and mastoid. Involvement of the left internal carotid artery (causing additional intermittent neurological symptoms related to cerebro-vascular insufficiency) was seen. Magnetic resonance imaging suggested the appearances to be most in keeping with an advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base involvement.

A nasopharyngeal biopsy demonstrated a chronic inflammatory infiltrate only. This was repeated twice due to the continued concern that on imaging this lesion appeared to be a malignancy. (The last biopsy was performed via a midfacial degloving approach to gain adequate tissue for analysis.) Subsequent cultures grew Pseudomonas species and a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Appropriate antibiotic treatment led to clinical improvement and reduction in the inflammatory markers, which had been raised. Intravenous antibiotics (vancomycin and meropenem) were given for 6 weeks, then oral antibiotics for a further planned 6 weeks. This was shortened to 2 weeks due to apparent clinical resolution.

Four months later the patient was re-referred with a left-sided VI palsy. Antibiotic treatment was administered for a further 6 weeks intravenously, then 6 weeks orally. Follow-up with further imaging showed an improving clinical situation over the next year and reparative bone changes along the skull base.

DISCUSSION

Other case reports have been written on unique presentations of central skull base infection similar to those presented here.1,2,4,6,7,9,11,12 The specific details of an individual case can be expected to vary, given the rarity of the condition. The region in which this condition arises is an anatomical “minefield,” and presenting symptoms will vary according to the precise location of infection. However, there are common findings among the different cases that should raise the possibility of this diagnosis (Table 1). These cases also highlight the problem of differentiating inflammatory pathology from a malignant cause. Inclusion in this table satisfies the inclusion criteria for the report, such that there was no immediate temporal relationship to an episode of otitis externa, with a reported prior history in only 2 out of 20 cases.

Table 1.

Details of Previously Reported Central or Atypical Skull Base Osteomyelitis Cases

| Reference | Age (y)/Sex/Comorbidity | Presenting Complaint | CN Palsies/Recovery with Treatment? | Blood Results at Presentation | Organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN, cranial nerve; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; WCC, white cell count; sp, species; DM, diabetes mellitus, CRP, C-reactive protein. | |||||

| Magliulo12 | 75/m/no | Headache, dysphagia | IX, X/no | High ESR, WCC | Pseudomonas sp |

| Rowlands4 | 77/m/DM | Dysphonia, dysphagia | X/no | High ESR, CRP | Pseudomonas sp |

| Cavel1 (6 cases) | 54–76/5 m, 1 f/DM (6 of 6) | Headache | VII, IX, X (2/6); VI, IX, X (1 of 6)/yes (2/3) | High ESR (5 of 6), CRP (3 of 6), WCC (2 of 6) | Pseudomonas sp (1 of 6), unreported (5 of 6) |

| Kulkani2 | 76/m/no | Headache, dysphagia, dysphonia | VI, X/yes | − | Pseudomonas sp |

| Huang7 | 47/m/no | Headache, dysarthria, dysphagia | IX, X, XI, XII/yes | High ESR, CRP | Proteus mirabilis |

| Grobman11 (3 cases) | 58/f/DM | Headache, hoarseness, dysphagia | IX, X, XI, XII/partial (IX only) | High ESR | Pseudomonas sp |

| 44/f/no | Headache, diplopia | II, IV, VI/partial | High ESR, WCC | Pseudomonas sp | |

| 57/f/DM | Headache, weight loss | IX, XII/yes | − | Pseudomonas sp, Staphylococcusaureus | |

| Malone9 | 34/m/no | Headache, diplopia, ‘thick’ tongue | VI, XII/yes | High ESR, WCC | Coagulase negative |

| Staphylococcus | |||||

| Chang6 (6 cases) | 50/m/DM | Headache (6 of 6), diplopia (5 of 6), dysphagia (3 of 6) | VI, IX, X, XII/partial | High ESR (5 of 6), WCC (2 of 6) | Eikenella corrodens |

| 13/m/DM | V(1,2), VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII | Staphylococcus aureus | |||

| 38/m/HIV + ve | VI, VII | Aspergillus | |||

| 72/m/DM | IX, X | Pseudomonas sp. | |||

| 33/m/no | VI | Group C streptococci | |||

| 35/m/DM | II, VI, VII, IX, X, XII | Streptococcus milleri | |||

It is widely reported that elderly, diabetic, predominantly male patients are most at risk.1 Case reports on this subject mainly describe diabetic or immunocompromised patients (17 of 24). Severe infection can adversely affect diabetic control, and there may well be need to use a sliding scale of insulin to achieve this. Of the 24 cases referenced, including the four cases presented here, the average age was 58 years and the sex distribution was 5:1 (M:F). An initial complaint of headache, often intractable, with symptoms related to individual CN palsies, is common to almost all cases. Involvement of both CN VI and the lower CNs (IX, X, XI) should in particular raise the suspicion of clival pathology.2 Ophthalmoplegia (most often sixth nerve paresis) and paresis of CN XII has been considered in the past to be pathognomonic of a malignant neoplasm of the nasopharynx. Although it is now clear that this combination is not exclusive to nasopharyngeal carcinoma, malignant tumors of some sort, often metastases, are still the most common cause reported in other series.3

Blood tests consistently demonstrate elevated acute-phase reactants, in particular the ESR (reported in 18 of 24 cases), whereas leucocytosis is less reliable (as is a lack of fever), although often seen at least to a moderate degree. One would not expect elevated acute-phase reactants with malignancy, so, given the potentially similar radiological findings, this may be a useful discriminator. Monitoring of the ESR is one of the key investigations that can help to guide how long antibiotic therapy is continued, and its normalization would appear to be a good indicator that the infection has resolved.

The imaging findings are of particular interest. The bone erosion and marrow infiltration of the basiocciput and/or petrous apex, as well as mass-like soft tissue swelling below the skull base, often raise concern that there is an underlying malignant process such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma or skull base metastases. This can lead to a delay in diagnosis because tissue samples from surgical biopsies may be sent for histology only and yield nondiagnostic results. Because of the dramatic imaging findings, an initial negative biopsy may be put down to sampling error. An important lesson is to always send biopsy material for microbiological analysis (including fungal and mycobacterial cultures) as well as histology; ultimately, this may lead to the correct diagnosis (and obviously dictate the antibiotic treatment regime).

Different imaging modalities may be helpful in the assessment of these patients, although MRI is probably the most important. Computed tomography findings may be lacking initially but may later demonstrate clear bony erosion. In one of our cases, and in a patient described by Rowlands et al,4 an initial CT scan failed to demonstrate bony destruction. Seabold et al found no CT evidence of bone erosion in 13 out of 35 patients with biopsy-confirmed cranial osteomyelitis.5 When present, the findings may fail to resolve for a long time after treatment is finished, so the use of CT for follow-up is questioned. Magnetic resonance imaging is a better soft tissue discriminator, offering good imaging of soft tissue planes around the skull base and abnormalities of the medullary cavity of bone.6 Malone et al6 describe typical findings of SBO to include marrow T1 hypointensity and T2 hyperintensity, although these are not specific. Clival enhancement (as is evident in Fig. 1B) can be seen both with SBO and malignant processes but is never normal. In terms of the differential diagnoses, the primary concern is of a malignant process, be it primary or secondary. Squamous cell carcinoma, lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and hematogenous metastases may all have similar MRI findings to those described for SBO. Also, non-neoplastic conditions such as Wegener's granulomatosis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, fibrous dysplasia, and Paget's disease can have similar MRI findings—the appearance on CT can help make the differentiation (particularly for the latter two conditions). Given that neither test is diagnostic, nor are these cases common, we advocate the use of both imaging modalities to get as much information as possible.

Various nuclear medicine imaging techniques have been advocated in suspected SBO including gallium-67 scintigraphy, indium-111 white blood cell scans, technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate (MDP) bone scans, and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). The latter two techniques may have an advantage over CT and MRI in detecting postoperative osteomyelitis and may be more useful in the follow-up of patients on antibiotics because marrow signal change may persist for up to 6 months after successful treatment.5 Although some centers advocate monitoring disease progression by the use of these scans, this is not currently the policy in our department. There is currently no imaging technique to replace the role of biopsy for microbiological culture in cases of suspected SBO.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most common pathogen implicated in osteomyelitis secondary to malignant otitis externa.7 This too seems true for central SBO, although other organisms have been reported, including Aspergillus,8 Gram-positive organisms,6 mycobacterium, and Candida.9 Given that antibiotic treatment for SBO is often required for prolonged periods, microbiological advice is recommended. Culture sensitivities will guide the choice of antibiotics, influenced by local prescribing policies. The length of time antibiotics are administered is variable among the cases reported, but in each case treatment was given for at least 1 month and up to 6 months. The Bone Infection Unit in Oxford, United Kingdom, often recommends up to 6 weeks of intravenous treatment followed by 6 to 12 months of oral medication, guided by clinical response. Adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen may also provide benefit. In cases of MOE, this may improve successful treatment by reversing tissue hypoxia, enhancing phagocytic killing of aerobic microorganisms, and stimulating neomicroangiogenesis.10 However, the very limited availability of this treatment modality makes it impractical for widespread consideration.

The patient may have a history of previous otitis externa, which was treated with apparent success, yet have no obvious activity at the time that SBO is present. None of our cases showed evidence of active otitis externa or granulations in the external ear canal. Where the two infections occur sequentially, the diagnosis would be considered sequelae of malignant otitis externa, and would therefore have been excluded from the patient group under discussion here. In the case described by Rowlands et al,4 resolution seemed apparent several months before the development of CN palsies and SBO. We, too, found this in two of our cases. It may well be that the initial otitis externa still represents the focus of infection, which could have lain quiescent within the temporal bone until later reactivated. Other authors conclude that the infection of central SBO may originate from paranasal sinus inflammatory disease or be hematogenous in origin.6

We report cases in which CN function has returned to a greater or lesser extent. Analyzing this can be difficult because function may return due to compensation of the contralateral side rather than true resolution of the affected side. The literature implies that this recovery is variable, and certainly not universal.6,11 However, this potential is relevant when counseling the patient and in aiding therapy (such as speech and language therapy) involved in the aftercare of the patient.

Some authors have advocated that with typical clinical picture and imaging findings together with a positive response to ciprofloxacin, the diagnosis can be made without the need for biopsies.1 However, we feel that even in a tertiary referral setting, this situation arises rarely and in varied form, such that it is not easy to diagnose clinically, and because the imaging findings can be so alarming, biopsy is inevitably required to ensure both the absence of malignancy and to aid subsequent microbiological advice. Clival biopsies can be taken endoscopically via the nose, the technique for which is well described.1

This is a serious condition, with potential for serious complication including the CN palsies with which it may present, cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningeal and brain extension, and death.

CONCLUSION

Cranial nerve palsies in the elderly diabetic or immunocompromised patient, with imaging findings of a lesion causing bony destruction in the central skull base, should raise the concern of a diagnosis of central SBO as well as of malignancy, and investigation for each should be concurrent. A past history of otitis externa, even if apparently resolved before the onset of the presenting symptoms, should further raise suspicion of an underlying infective cause. Prompt commencement of antibiotic therapy is desirable to lower the risk of potential sequelae, which can prove to be fatal. The length of time that this therapy is continued should be guided by clinical findings, normalization of inflammatory markers, and resolution on MRI. Surgery has limited but very important roles: (1) providing tissue that helps exclude a neoplastic pathology and (2) allowing reliable culture of the microorganism responsible.

REFERENCES

- Cavel O, Fliss D M, Segev Y, Zik D, Khafif A, Landsberg R. The role of the otorhinolaryngologist in the management of central skull base osteomyelitis. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21(3):281–285. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Lee A, Lee J H. Sixth and tenth nerve palsy secondary to pseudomonas infection of the skull base. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(5):918–920. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane J R. Combined VIth and XIIth cranial nerve palsies: A clival syndrome. Neurology. 2000;54:1540–1541. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.7.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands R G, Lekakis G K, Hinton A E. Masked pseudomonal skull base osteomyelitis presenting with a bilateral Xth cranial nerve palsy. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116:556–558. doi: 10.1258/002221502760132700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seabold J E, Simonson T M, Weber P C, et al. Cranial osteomyelitis: diagnosis and follow-up with In-111 white blood cell and Tc-99m methylene diphosphonate bone SPECT, CT, and MR imaging. Radiology. 1995;196:779–788. doi: 10.1148/radiology.196.3.7644643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone D G, O'Boynick P L, Ziegler D K, Batnitzky S, Hubble J P, Holladay F P. Osteomyelitis of the skull base. Neurosurgery. 1992;30(3):426–431. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199203000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K-L, Lu C-S. Skull base osteomyelitis presenting as Villaret's syndrome. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2006;15:255–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kountakis S E, Kemper J V, Jr, Chang C Y, DiMaio D J, Stiernberg C M. Osteomyelitis of the base of skull secondary to Aspergillus. Am J Otolaryngol. 1997;18:19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(97)90043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang P C, Fischein N J, Holliday R A. Central skull base osteomyelitis in patients without otitis externa: imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1310–1316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J C, Gates G A, Lerner C, Davis M G, Jr, Mader J T, Dinesman A. Adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen in malignant external otitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:89–93. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880010093022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobman L R, Ganz W, Casiano R, Goldberg S. Atypical osteomyelitis of the skull base. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:671–676. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198907000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magliulo G, Varacalli S, Ciofalo A. Osteomyelitis of the skull base with atypical onset and evolution. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:326–330. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]