Abstract

We investigated whether the human placenta plays a role in embryonic and fetal hematopoietic development. Two cell populations—CD34++CD45low and CD34+CD45low—were found in chorionic villi. CD34++CD45low cells display many markers that are characteristic of multipotent primitive hematopoietic progenitors and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Clonogenic in vitro assays showed that CD34++CD45low cells contained colony-forming units-culture (CFU-C) with myeloid and erythroid potential and differentiated into CD56+ NK cells and CD19+ B cells in culture. CD34+CD45low cells were mostly enriched in erythroid- and myeloid-committed progenitors. The number of CD34++CD45low cells increased throughout gestation in parallel with placental mass. However, their density (cells per gram of tissue) reached its peak at 5–8 weeks, decreasing more than sevenfold from the ninth week onward. In addition to multipotent progenitors, the placenta contained intermediate progenitors, indicative of active hematopoiesis. Together, these data suggest that the human placenta is potentially an important hematopoietic organ, opening the possibility of banking placental HSCs along with cord blood for transplantation.

Keywords: Human placenta, Embryonic and fetal hematopoiesis, Multipotent hematopoietic progenitor

INTRODUCTION

Human hematopoiesis initiates around 16–18.5 days of development in the extraembryonic niche provided by the yolk sac.1 The hematopoietic output of the yolk sac is gradually replaced by sequential intraembryonic sites, such as the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM), which is generated from the para-aortic splanchnopleure region,2 and, later on, by the embryonic liver. Cells resembling primitive hematopoietic progenitors, which co-express the cell surface antigens CD34 and CD45, are first detected in the human AGM at day 27,3 and the population quickly expands until their disappearance by day 40. The embryonic liver is the next hematopoietic tissue to become active, around 5–6 weeks of gestation,4 with output peaking around the end of the second trimester and gradually diminishing throughout the remainder of fetal development. Finally, the fetal bone marrow (BM) develops hematopoietic activity at the start of the second trimester.5

During the last decade, no other extra- or intraembryonic hematopoietic region was identified to be part of the orchestrated and site-specific hematopoiesis occurring during the embryonic and fetal phases of human development. In the current model of developmental hematopoiesis, intraembryonic hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), presumably generated in the AGM region, establish definitive hematopoiesis. However, this theory is weakened by the observation that the AGM region, which contains a limited number of HSCs, is active for only a very short period in both humans and mice. Possible explanations include either an extremely rapid and efficient migration of AGM-derived HSCs to the liver or the existence of another hematopoietic niche that has yet to be identified.

The observation that the mouse placenta contains transplantable hematopoietic cells was reported some 40 years ago by Till and McCullough6 and, later on, by Dancis et al.7 The placental hematopoietic progenitors reconstituted recipients similarly to BM cells and their repopulating activity did not depend on the organ’s blood supply,8 suggesting the existence of an endogenous HSC population. In 1979, Melchers showed that the murine placenta contains hematopoietic progenitors before the fetal liver is hematopoietically active.9 Two independent groups recently reported that the mid-gestation mouse placenta is a rich hematopoietic organ that contains high-proliferative-potential colony-forming cells of fetal origin that demonstrate both myeloid and erythroid cell potential in vitro10 and fully reconstitute the hematopoietic systems of adult, lethally irradiated recipient mice.11 Furthermore, the hematopoietic activity of the mouse placenta is present before the placental circulation is established, prior to chorio-allantoic fusion, demonstrating that the placenta is not only a niche but also a source of hematopoietic cells that functions during the same time period as the AGM.12,13 These recent reports support to an expansion of the current model of embryonic hematopoiesis to include the placenta as a contributing site.10, 11, 14.

The hematopoietic potential of the human placenta is presently unknown. In previous reports, CD235a+ (glycophorin A) CD34−CD45− erythroblast cells, but not CD34+CD45+ progenitors, have been identified in first and second trimester placentas.15, 16 Recently, a multipotent cell population expressing markers of mesenchymal and embryonic stem cells was described in crude preparations of term placental cells 17, 18 and in association with the amniotic epithelium.19 However, the hematopoietic potential of these placental cell populations was not been investigated, a gap in knowledge that this study was designed to fill. The full report of the study has been recently published.20

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of placental hematopoietic progenitors

This study was approved by the University of California at San Francisco Committee on Human Research. We used the basic method that our group devised for isolating human placental cells21 (n=70, from 5.4 to 39.5 weeks of gestation) with a few modifications that significantly improved the recovery of hematopoietic cells. In particular, we modified the technique by adding a final enzymatic digestion treatment of the placental cell preparations with 181 U/ml collagenase I-A, 0.12 mg/ml DNase I, 0.70 mg/ml hyaluronidase type I-S, and 1 mg/ml BSA in PBS at 37°C. Digestion continued for various periods of time (5 minutes to 1 hour) until total cellular dissociation was observed. Then the cells were centrifuged over Nycoprep (1.077 g/ml; Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC) for 30 minutes (25°C) at 600 × g. Further purification of CD34++CD45low or CD34+CD45low cells was achieved by staining the cell suspensions with directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): anti-CD34-allophycocyanin (APC) (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) and anti-CD45-phycoerythrin (PE) (Invitrogen/Caltag, Carlsbad, CA), and sorting with a FACSDiva or a FACSAria (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Isolation of hematopoietic progenitors from umbilical cord blood (UCB) and fetal BM

Samples were processed immediately after they were obtained by sieving through a 200-µm sieve mesh (fetal BM) or diluting 1:1 with PBS (full-term UCB) before centrifugation over Nycoprep. The resulting light-density cell suspension of fetal BM or UCB was used for phenotypic analyses, fluorescence in situ hybridization, or cell-sorting experiments as described below for placental cells. At least three different preparations of each type were analyzed.

Monoclonal antibodies

Isotype-matched control IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b and IgG3 were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA), and IgM was obtained from Invitrogen/Pharmingen. They were conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), PE or APC as indicated in the figure legends. Propidium iodide (PI) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. and used at a final concentration of 1 µg/ml. The antibodies that were used for cell separation and immunofluorescence included anti-CD34-PE (8G12, IgG1, Invitrogen/Caltag), anti-CD34-APC (581, IgG1, Beckman Coulter), anti-CD45-FITC, -PE, and -APC (HI30, IgG1, Invitrogen/Caltag), anti-CD38-PE (HB-7, IgG1, BD Biosciences), anti-CD56-FITC (C5.9, IgG2b, Exalpha, Inc., Boston, MA), anti-HLA-DR-PE (L243, IgG1, BD Biosciences), anti-CD33-PE (P67.6, IgG1, BD Biosciences), anti-CD13-PE (L138, IgG1, BD Biosciences), anti-CD38-PE (HIT2, IgG1, BD Biosciences), anti-CD4-PE (SK3, IgG1, BD Biosciences), anti-CD8a-FITC or -PE (HIT8a, IgG1, BD Biosciences), anti-CD235a-FITC or -PE (11E4B7.6, IgG1, Beckman Coulter), anti-erythropoietin receptor (EpoR)-FITC or -PE (38409, IgG2b, R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN), anti-CD117-PE (YB5.B8, IgG1, BD Biosciences), anti-CD133-PE or -APC (AC133, IgG1, Milteny Biotec, Inc., Auburn, CA), anti-CD31-PE (WM-59, IgG1, BD Biosciences), anti-CD41-PE (HIP8, IgG1, BD Biosciences), anti-CD14-FITC, -PE, or -APC (MΦII9, IgG2b, BD Biosciences, IgG2b, BD Biosciences), anti-CD15-FITC (MMA anti-Leu-M1, IgM, BD Biosciences), anti-VEGFR2-PE (89106, IgG1, R&D Systems), anti-Tie2-PE and -APC (83715, IgG1, R&D Systems), and anti-CD3-FITC, -PE, or -APC (SK7, anti-Leu-4, IgG1, BD Biosciences).

Cytokines

Recombinant human stem cell factor (SCF), Flt-3/Flk-2 ligand (FL), interleukin (IL)-3, IL-6, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), thrombopoietin (TPO), IL-7, IL-15, and erythropoietin (Epo) were purchased from R&D Systems. All these factors were used at 20 ng/ml, except SCF (50 ng/ml), FL (100 ng/ml), and Epo (10 U/ml), concentrations that generated the maximal number of colonies in colony-forming units-culture (CFU-C) assays and optimal growth in liquid cultures.22

Hematopoietic progenitor assays

To enumerate CFU-C, we set up methylcellulose clonal cultures of sorted CD34++CD45low and CD34+CD45low placental cells or UCB at a density of 5 × 102/plate (35 mm, BD Falcon, BD Biosciences) in either Methocult GF H4435 (StemCell Technologies, Inc. Vancouver, BC, Canada) containing 30% FBS and supplemented with 50 ng/ml SCF, 20 ng/ml GM-CSF, 20 ng/ml G-CSF, 10 U/ml Epo, 20 ng/ml IL-3, and 20 ng/ml IL-6, or serum-deprived medium (SDM),23 supplemented with 1.2% 4000 centipoises methyl cellulose (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co.) and the same cytokine combination. In some experiments, characterized FBS (Hyclone) was added to SDM at the concentrations indicated in the figures. Colonies containing red cells were scored as burst-forming unit erythroid (BFU-E) after 3–4 weeks of growth at 37°C, in 5% CO2 in air. CFU-granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM) colonies that expressed CD14 and CD15 (myeloid progeny) were identified by colony morphology and flow cytometry.22 CFU-mix colonies contained both granulocyte-macrophage and erythroid progenitors.

Lymphoid- and myelo-erythroid-megakaryocyte differentiation in liquid cultures

After sorting, CD34++CD45low cells were counted, washed in PBS containing 0.5% BSA, and cultured at 5 × 103 to 7.5 × 103 cells/ml in 48-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) in the presence of SDM supplemented with 50 ng/ml SCF, 100 ng/ml FL, 20 ng/ml IL-15, 20 ng/ml IL-7, 20 ng/ml GM-CSF, 20 ng/ml IL-3 (lymphoid-permissive conditions22), or a combination of 50 ng/ml SCF, 100 ng/ml FL, 20 ng/ml IL-15, 20 ng/ml GM-CSF, 20 ng/ml IL-3, 20 ng/ml TPO, and 10 U/ml Epo (myelo-erythroid-megakaryocytic-permissive conditions24). Medium was refreshed twice a week by changing half the volume and adding fresh cytokines. After 21–23 days in culture, cells were harvested, washed with PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA, and stained with directly conjugated mAbs before flow cytometric analyses.

Immunofluorescence and flow cytometry

Cell surface phenotypic analyses were performed as previously described25 using a two-laser FACSCalibur or LSR II cytometer (BD Biosciences) and CellQuest (BD Biosciences) or FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR) software.

RESULTS

The placenta contains hematopoietic progenitor populations that are fetal in origin

The placenta is a sizable, but transient, fetal organ that develops in advance of the embryo, which it supports by performing a myriad of transport functions. Because of its multiple functions, the placenta is a complex organ comprised of many cell types 26: mononuclear cytotrophoblast (CTB), multinucleated syncytiotrophoblasts, hematopoietic (CD45+) cells, endothelial cells, mesenchymal cells, fibroblast among others. To investigate the possibility that the placenta supports hematopoietic development, the first step was to adapt our current method of enzymatic dissociation of the placenta 21 to serve our needs of obtaining a maximum number of hematopoieic progenitors. We stained freshly isolated placental cellular suspensions obtained by different methods (enzymatic vs. mechanical disruption) with mAbs against cell-surface antigens displayed by hematopoietic progenitor populations present in embryonic and fetal tissues, followed by flow cytometric analyses. The enzymatic digestion of placenta was a superior method compared with mechanical disruption to obtain higher numbers of CD34++CD45+ cells. While an incubation of the placental tissue with collagenase I followed by digestion with trypsin sufficed for the optimal isolation of CTB, in our experience a third enzymatic digestion with collagenase rendered an optimal recovery of hematopoietic progenitors. FACS analyses performed on the sequential fractions obtained at the different steps of the preparation indicated that the number of hematopoietic progenitors (defined by CD34++CD45low cell surface phenotype) obtained with the three-enzymatic digestion method was significantly increased when compared the cells obtained by the classical CTB two-step dissociation method. We detected 0.26–0.38% of CD34++CD45low cells with the double enzymatic digestion method vs. 0.48–1% obtained with the triple enzymatic digestion method, in placentas ranging from 7 to 9 wks of gestation (n=3), suggesting that the hematopoietic progenitor compartment is located deep within the placental tissue. Once that the dissociation method was optimized, the placenta samples included in this study ranged from 5.4 to 39.5 weeks of gestation and all the samples were processed and analyzed in identical manner. We searched for hematopoietic progenitors in the human placenta at different gestational ages by using flow cytometry and monoclonal antibodies that specifically react with several markers expressed by early hematopoietic progenitors and HSCs. We focused on cells that expressed both CD34 and CD45 cell surface markers,27 which allowed discrimination of the hematopoietic population from endothelial lineages with a CD34+CD45− phenotype. Two populations were observed at various frequencies within the ranges indicated: CD34+CD45low (2.86–20.91%) and CD34++CD45low (0.03–1.2%) (n=59) (Fig.1A). To determine the phenotypic profile of the placental hematopoietic populations, we investigated their expression of antigens displayed by multipotent progenitors and HSCs. As shown in Fig. 1B, the majority of CD34++CD45low and CD34+CD45low cells were phenotypically comparable to the equivalent populations isolated from fetal liver and BM, with some of these cells displaying expression of CD133, CD90 (Thy-1), HLA-DR, low levels of CD117 (c-kit), CD33 and high levels of CD31 (PECAM-1). Neither CD34++CD45low nor CD34+CD45low cells expressed detectable levels of CD41, CD4 (Fig. 1B), CD38, CD95 or CXCR4 (data not shown).

Fig. 1. Phenotypic characterization of placental hematopoietic progenitors.

Freshly isolated light-density cell suspension from a second trimester (20 wk in A) and a first trimester (12 wk in B) placentas were stained with the indicated mAbs and PI, the exclusion of which identifies dead cells. (A) The forward versus side scatter profile of 105 cells is shown, and an electronic gate was set to exclude PI+ cells (not shown). Isotype-matched negative controls are included. 2 × 105 cells were acquired using a FACSCalibur and analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson); the percentages of positive cells are indicated. (B) Staining of a 12 wk placental preparation with mAbs against markers expressed by hematopoietic progenitors is shown. The results are representative of 16 experiments (10 of first trimester and 6 of second trimester placental cellular suspensions).

To confirm the fetal origin of the placental cells, we isolated CD34++CD45low population by cell sorting from a placenta obtained at 19 weeks of gestation from a pregnancy in which the fetus was male; the equivalent population sorted from BM of the same sample served as a positive control. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analyses were performed using probes that hybridized to specific repeat sequences on either the X or the Y chromosome. Sorted placental hematopoietic progenitors and the fetal BM cells carried both an X and a Y chromosome, showing that the CD34++CD45low population was fetal in origin (data not shown).

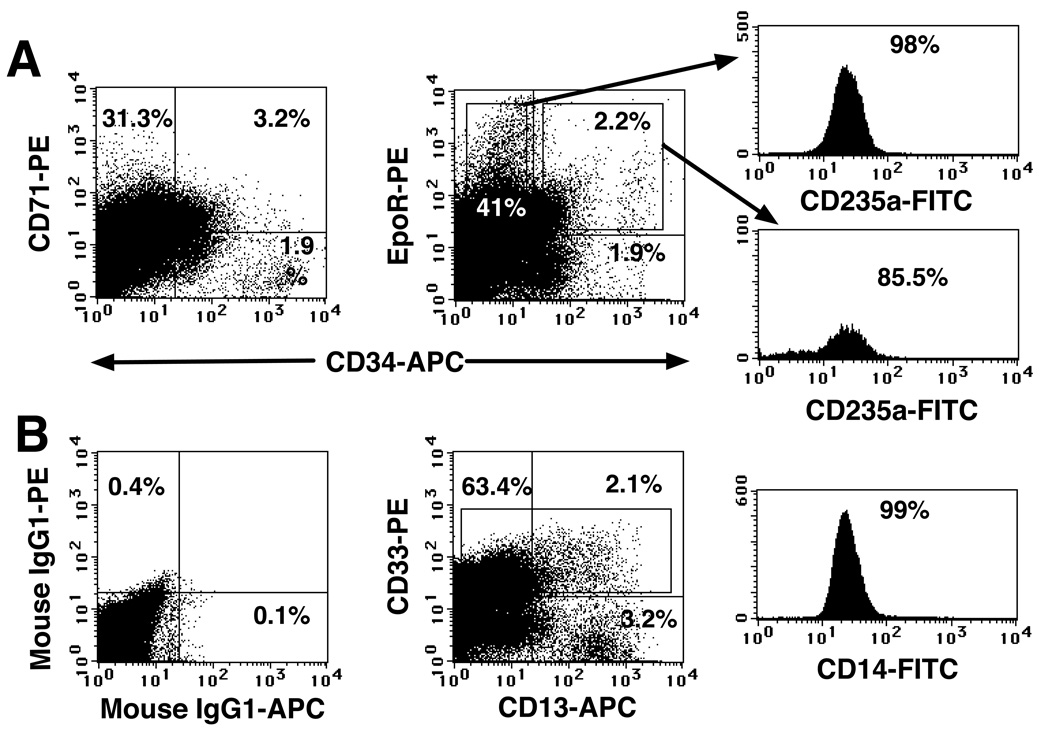

The placenta contains erythroid- and myeloid-committed progenitors

We investigated whether the placenta is an active hematopoietic niche by searching for progenitors committed to several hematopoietic lineages at different stages of development. These experiments focused on antigens that are expressed by cells differentiating along specific hematopoietic pathways, such as CD71, EpoR, and CD235a (glycophorin A), which mark erythroid commitment28, 29 and CD13, CD33 and CD14, which mark the myeloid lineage Fig. 2A shows the abundance of CD71 and EpoR expression among CD34+CD45low population. Many of these cells did not express the mature erythrocyte marker CD235a, suggesting that they comprise early erythroid precursors. The four-color flow cytometric analyses also indicated an abundance of CD235a+ cells that expressed EpoR and CD71 and variable levels of CD34, suggesting the presence of intermediate- (CD34+) and late-stage (CD34−) erythroid precursors in the placenta.

Fig. 2. Erythroid and myeloid progenitors were present in the placenta throughout gestation.

(A) A freshly isolated light-density cell suspension from a 20 wk placenta was stained with the indicated mAbs against erythroid markers, and three-color FACS was performed and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. (B) Four-color FACS analysis (FITC, PE, APC and PI) of a 22 wk light-density placental cell suspension using mAbs that recognized myeloid progenitors. In all the analyses, 1 × 105 to 2 × 105 viable cells were acquired and analyzed. The results are representative of five experiments.

We investigated the presence of myeloid precursors among CD34+CD45low cells by staining placental cell preparations with mAbs against cell surface markers CD33 and CD13, displayed by the myeloid progenitors, as well as CD14, which is expressed by mature myeloid cells. Four-color FACS results (Fig. 2B) indicated that about half of the CD13+ cells displayed CD33, as well as CD14, indicating that half of the CD13+ cells belong to the myeloid lineage. The remaining CD13+CD33−CD14− cells, possibly mesenchymal, were nonhematopoietic, since they lacked CD45 expression (data not shown). CD14 expression on CD13+CD33+ cells is accompanied by a loss of CD34 (data not shown); therefore, they are mature myeloid cells. CD14+ cells are an abundant cell population in the chorionic villi, composed of specialized resident macrophages (Hofbauer cells) that can be found from 4 weeks of gestation until term,30 constituting the first mature leukocyte population in the placenta.

The placenta is richer in hematopoietic progenitors in the embryonic phase of development than in the fetal phase

Since the frequency of CD34++CD45low cells (0.03–1.2%) varies during gestation, we estimated the number of hematopoietic progenitors in this compartment at various times by analyzing a large set of samples (n=59) and expressing the results as the number of CD34++CD45low cells isolated per gram of tissue. The total number of CD34++CD45low cells steadily increased as the placenta grew (Fig. 3A). However, the highest numbers per gram of tissue were recovered during the embryonic period (Fig. 3B). Specifically, the frequency of CD34++CD45low cells was about 7 times higher at 5 to 8 weeks (n=18) than at 9 to 12 weeks (n=15), after which time the values remained relatively constant. This finding was statistically significant (P < 0.001) as determined by an unpaired t-test.

Fig. 3. The hematopoietic compartment of the placenta changes during gestation.

(A) Data represent the median of total CD34++CD45low placental cells grouped by gestational age (in weeks, n=59). (B) A plot of the median number of CD34++CD45low cells per gram of tissue, also grouped by gestational age. The width of the boxes is proportional to the sample size (5–8 wks, n=18; 9–12 wks, n=15; 13–16 wks, n=9; 17–20 wks, n=7; 21–24 wks, n=7 and 38–40 wks, n=3).

CD34++CD45low and CD34+CD45low placental populations contain multipotent hematopoietic progenitors

Clonogenic hematopoietic progenitor assays were performed with sorted CD34++CD45low and CD34+CD45low cells and regardless of gestational age, both populations produced mostly myeloid progenitor colonies (CFU-GM), with a small number of mixed colonies that contained both myeloid and erythroid cells (Fig. 4A). No colonies that were entirely erythroid in origin (BFU-E) were observed in any experiment. The myeloid and erythroid nature of the colonies was assessed both by visualization of the colonies’ morphology and by FACS, for which we stained individually plucked colonies with mAbs against CD45, CD14 and CD15 (Fig. 4B). These findings suggested that both CD34++CD45low and CD34+CD45low cells from the human placenta contained multipotent hematopoietic progenitors that were able to generate both myeloid and erythroid colonies.

Fig. 4. Colony-forming activity of placental hematopoietic progenitors.

(A) Sorted populations from the placentas at the indicated gestational ages were plated in Methocult medium (StemCell Technologies) and scored at 3.5 wk of culture. Cells were plated at a density of 500 cells/plate in 1 ml of medium/plate using 35-mm plates (8–11 replicates and 4 experiments). CFU-GM refers to myeloid colonies (in solid bars), and CFU-mix refers to colonies containing both myeloid and erythroid cells (in striped bars). (B) Individual colonies generated from CD34++CD45+ cells sorted from the 16 wk placenta depicted in panel A were plucked and then stained with the indicated directly conjugated mAbs and PI. Viable cells (104) were acquired and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Colony 1 was visually identified as a CFU-mix, while colonies 2, 3 and 4 were identified as CFU-GM. The results are representative of two experiments where a total of 22 colonies were analyzed.

To further investigate the hematopoietic multipotency of placental CD34++CD45low cells, we performed in vitro differentiation assays in liquid culture conditions that support multilineage differentiation, including generation of lymphoid cells.22, 31 In three experiments, sorted CD34++CD45low cells were simultaneously cultured in lymphoid-permissive (Fig. 5A) or myelo-erythroid-megakaryocytic-permissive (Fig. 5B) conditions, in the absence of serum and stroma, and in the presence of a defined mixture of recombinant cytokines and SDM. After 21 days in culture the cells were harvested, counted, and stained with the mAbs indicated. CD34++CD45low cells generated a low level (1–6%) of CD56+ lymphoid cells that coexpressed CD45 (data not shown) in cultures supported by lymphoid-permissive conditions (SCF+FL+IL-15+IL-7+IL-3+GM-CSF, Fig. 5A).22 In addition, a minor population of CD19+ cells (0.2–2%), indicative of B-cell development, was detected. These cells did not express CD20 or surface bound IgM, but they expressed the lymphoid progenitor marker CD10 (data not shown), suggesting that they were pre-B cells that did not complete the differentiation process. The progeny of CD34++CD45low cells also contained a high number of CD33 myeloid cells, but did not express CD235a, which characterizes cells belonging to the erythroid lineage. Most of the CD33+ cells displayed markers of dendritic cells, such as CD83 and CD86 (not shown). When CD34++CD45low cells were cultured for the same period of time in myelo-erythroid-permissive conditions (SCF+FL+IL-3+GM-CSF+Epo+TPO, Fig. 5B),22, 32 the phenotypic characterization of their progeny demonstrated that the cells could differentiate along these lineages, while unable to generate CD56+ or CD19+ lymphoid cells. Differentiation of CD34++CD45low cells along the erythroid lineage was observed, since CD235a was expressed by 50–75% of the progeny. Myeloid differentiation was apparently incomplete, as only 1–5% of CD33+ cells expressed the mature monocyte marker CD14 (not shown).

Fig. 5. CD34++CD45+ placental cells have multilineage hematopoietic potential.

Sorted CD34++CD45low cells from a 19 week placenta were cultured at 5 × 103 cells/ml in 48-well plates in lymphoid-permissive conditions (SDM supplemented with SCF+FL+IL-7+IL-15+GM-CSF+IL-3) (A) or in myelo-erythroid permissive conditions (SDM supplemented with SCF+FL+Epo+GM-CSF+TPO) (B). After 21 days in culture, cells were harvested, counted, and stained with the indicated mAbs and PI. Viable cells (5 × 104) were acquired and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The results are representative of three experiments.

The detection of 0.1–0.3% of CD34++CD45low cells in full-term placentas led us to investigate their hematopoietic potential in clonogenic methylcellulose assays. The total number of sorted CD34++CD45low and CD34+CD45low cells recovered was higher than that from samples of first or second trimester placentas (2.6 × 104 to 8 × 104 CD34++CD45low cells and 1.6 × 104 to 1.8 × 104 CD34+CD45low cells, n=2). However, the CD34++CD45low population failed to produce CFU-C, and the more mature CD34+CD45low cells generated very low numbers of CFU-GM (0.3–1.3/500 plated cells) and CFU-mixed (0.5–1.4/500 plated cells). Interestingly, CD34+CD45low cells isolated from term placentas produced low numbers of pure erythroid colonies (BFU-E; 0.7–0.8/500 plated cells), whereas the hematopoietic populations isolated from first or second trimester placentas did not. This suggests a qualitative difference in the functional capacity of the early as compared to the term placental hematopoietic progenitors.

DISCUSSION

In this study we show that the human placenta contains hematopoietic progenitors at different stages of development, including multipotent and lineage-committed cells that are undergoing in situ erythropoiesis and myelopoiesis. Our findings suggest that this organ supplements the output of other intraembryonic hematopoietic sites, such as the AGM and/or the fetal liver. Because of the transient nature of embryonic and fetal hematopoietic niches, the density of these cells begins to decline at the onset of the fetal phase of development. Simultaneously, cytotrophoblast invasion of the uterus and remodeling of its vasculature diverts maternal blood flow to the placenta, a critical transition in pregnancy when oxygen tension at the maternal-fetal interface rises from ~2 to 8%.33 We have previously showed that the relatively hypoxic environment of the chorionic villi during the embryonic period stimulates proliferation of trophoblast progenitors,33 which differentiate as oxygen levels rise. Placental hematopoietic progenitors and HSCs might undergo a similar process. The relative importance of the contribution from this site, in terms of timing and numbers of cells generated, is not yet known. In the mouse, the hematopoietic activity of the placenta manifests before the liver, occurs simultaneously with the AGM, and peaks around mid-gestation.10

Human placental hematopoietic progenitors display phenotypic and functional characteristics of their counterparts in other locations, such as the AGM, fetal liver, and fetal BM.2, 3, 34 CD34++CD45low cells from first and second trimester placentas expressed markers that typify multipotent hematopoietic progenitors, e.g., CD133, CD90, CD117, CD33, and HLA-DR. The functional characterization of placental CD34++CD45low cells demonstrated their hematopoietic potential, i.e. the ability to generate both myeloid and erythroid colonies. However, neither CD34++CD45low nor CD34+CD45low cells isolated from first or second trimester tissues produced BFU-E in standard methylcellulose cultures that support the generation of erythroid colonies. In contrast, progenitors isolated from term placentas produced BFU-E in low but measurable numbers. We interpret these differences as an indication that the placental niche is unique as compared to other hematopoietic environments and that the molecular components change as the placenta, a rapidly growing but transient organ, matures. Preliminary experiments using both conventional immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy showed that that cells co-expressing CD34 and CD45 reside in primarily two locations: near placental blood vessels of all sizes and within the mesenchymal compartment of the villous cores. Regardless of their location, these cells were frequently found in close contact with either endothelial CD34+CD45− cells or vimentin+ mesenchymal cells. Future experiments will address the nature of the placental hematopoietic niche.

Definitive multipotent hematopoietic progenitors and HSCs are able to generate cells that contribute to all the blood lineages. Are the human placental progenitors embryonic in nature (with exclusive myelo-erythroid potential) or are they capable of establishing definitive hematopoiesis (myelo-erythroid and lymphoid potential)? Our data indicate that CD34++CD45low placental cells generate multilineage progeny, including CD56+ and CD19+ lymphoid cells, in very restricted cell culture conditions (in the absence of serum and stroma) and myelo-erythroid progeny. The discrepancy between the relatively incomplete myeloid differentiation of CD34++CD45low placental cells in liquid cultures (Fig.5B) versus the full differentiation into CD14+ and/or CD15+ mature myeloid cells in methylcellulose cultures (Fig4B) could be due to slight differences in time and culture conditions. Overall our data suggest that, as in the mouse, human placental progenitors can be categorized as definitive progenitors.

In summary, our findings not only invite many questions regarding human developmental hematopoiesis during the embryonic and fetal phases, but they could also open the potential clinical use of placentas as a possible source of additional human progenitors with hematopoietic potential. Future functional studies will better define the placental hematopoietic niche, its contribution in the embryo/fetus as a source of HSCs, and the full potential of placental hematopoietic progenitors in engraftment assays.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Ms. Tara Rambaldo (Laboratory of Cell Analysis, UCSF) for the cell sorting of placental, bone marrow and UCB samples and Ms. Jean Perry (RN MS NP, UCSF Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences) for her assistance in obtaining full-term placental and UCB samples. We also thank Drs. Olga Genbacev, Joseph M. McCune and Yuet W. Kan for their helpful comments and suggestions in all aspects of the project.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Sandler Family Foundation (UCSF Innovations in Basic Sciences Award), NIH/DK068441, NIH/R21HD055328 and Blood Systems Inc.

Contributor Information

Alicia Bárcena, Email: Alicia.Barcena@ucsf.edu.

Marcus O. Muench, Email: mmuench@bloodsystems.org.

Mirhan Kapidzic, Email: Mirhan.Kapidzic@ucsf.edu.

Susan J. Fisher, Email: Sfisher@cgl.ucsf.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Luckett WP. Origin and differentiation of the yolk sac and extraembryonic mesoderm in presomite human and rhesus monkey embryos. Am J Anat. 1978;152:59–97. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001520106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tavian M, Coulombel L, Lutton D, San Clemente H, Dieterlen-Lièvre F, Péault B. Aorta-associated CD34+ hematopoietic cells in the early human embryo. Blood. 1996;87:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tavian M, Hallais MF, Peault B. Emergence of intraembryonic hematopoietic precursors in the pre-liver human embryo. Development. 1999;126:793–803. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miglicaccio G, Miglicaccio AR, Petti S, et al. Human embryonic hemopoiesis. Kinetics of progenitors and precursors underlying the yolk sac→liver transition. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:51–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI112572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charbord P, Tavian M, Humeau L, Peault B. Early ontogeny of the human marrow from long bones: an immunohistochemical study of hematopoiesis and its microenvironment. Blood. 1996;87:4109–4119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Till JE, McCulloch EA. A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiat Res. 1961;14:213–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dancis J, Jansen V, Gorstein F, Douglas GW. Hematopoietic cells in mouse placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1968;100:1110–1121. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(15)33411-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dancis J, Jansen V, Brown GF, Gorstein F, Balis ME. Treatment of hypoplastic anemia in mice with placental transplants. Blood. 1977;50:663–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melchers F. Murine embryonic B lymphocyte development in the placenta. Nature. 1979;277:219–221. doi: 10.1038/277219a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez-Silva M, Belo-Diabangouaya P, Salaun J, Dieterlen-Lievre F. Mouse placenta is a major hematopoietic organ. Development. 2003;130:5437–5444. doi: 10.1242/dev.00755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ottersbach K, Dzierzak E. The murine placenta contains hematopoietic stem cells within the vascular labyrinth region. Dev Cell. 2005;8:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeigler BM, Sugiyama D, Chen M, Guo Y, Downs KM, Speck NA. The allantois and chorion, when isolated before circulation or chorio-allantoic fusion, have hematopoietic potential. Development. 2006;133:4183–4192. doi: 10.1242/dev.02596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corbel C, Salaun J, Belo-Diabangouaya P, Dieterlen-Lievre F. Hematopoietic potential of the pre-fusion allantois. Dev Biol. 2007;301:478–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gekas C, Dieterlen-Lievre F, Orkin SH, Mikkola HK. The placenta is a niche for hematopoietic stem cells. Dev Cell. 2005;8:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Challier JC, Carbillon L, Kacemi A, et al. Characterization of first trimester human fetal placental vessels using immunocytochemical markers. Cell Mol Biol. 2001;47 Online Pub:OL79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Challier JC, Galtier M, Cortez A, Bintein T, Rabreau M, Uzan S. Immunocytological evidence for hematopoiesis in the early human placenta. Placenta. 2005;26:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukuchi Y, Nakajima H, Sugiyama D, Hirose I, Kitamura T, Tsuji K. Human placenta-derived cells have mesenchymal stem/progenitor cell potential. Stem Cells. 2004;22:649–658. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-5-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yen BL, Huang HI, Chien CC, et al. Isolation of multipotent cells from human term placenta. Stem Cells. 2005;23:3–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miki T, Lehmann T, Cai H, Stolz DB, Strom SC. Stem cell characteristics of amniotic epithelial cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1549–1559. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bárcena A, Kapidzic M, Muench MO, et al. The human placenta conatins early multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. 2008 (submitted for publication) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher SJ, Cui TY, Zhang L, et al. Adhesive and degradative properties of human placental cytotrophoblast cells in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:891–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.2.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muench MO, Bárcena A. Broad distribution of colony-forming cells with erythroid, myeloid, dendritic cell, and NK cell potential among CD34(++) fetal liver cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:4902–4909. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bárcena A, Park SW, Banapour B, Muench MO, Mechetner EB. Expression of Fas/CD95 and bcl-2 in primitive hematopoietic progenitors in the human fetal liver. Blood. 1996;88:2013–2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muench MO, Bárcena A. Megakaryocyte growth and development factor is a potent growth factor for primitive hematopoietic progenitors in the human fetus. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:1050–1056. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000127020.00090.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bárcena A, Muench MO, Galy AHM, et al. Phenotypic and functional analysis of T-cell precursors in the human fetal liver and thymus. CD7 expression in the early stages of T-and myeloid-cell development. Blood. 1993;82:3401–3414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Red-Horse K, Zhou Y, Genbacev O, et al. Trophoblast differentiation during embryo implantation and formation of the maternal-fetal interface. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:744–754. doi: 10.1172/JCI22991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lansdorp PM, Sutherland HJ, Eaves CJ. Selective expression of CD45 isoforms on functional subpopulations of CD34+ hemopoietic cells from human bone marrow. J Exp Med. 1990;172:363–366. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olweus J, Terstappen LW, Thompson PA, Lund-Johansen F. Expression and function of receptors for stem cell factor and erythropoietin during lineage commitment of human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1996;88:1594–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lammers R, Giesert C, Grunebach F, Marxer A, Vogel W, Buhring HJ. Monoclonal antibody 9C4 recognizes epithelial cellular adhesion molecule, a cell surface antigen expressed in early steps of erythropoiesis. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:537–545. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00798-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castelucci M, Kaufmann P. Hofbauer cells. In: Benirscke K, Kaufmann P, editors. Pathology of the Human Placenta. 2nd edition. New York: Springer; 1992. pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muench MO, Humeau L, Paek B, et al. Differential effects of interleukin-3, interleukin-7, interleukin 15, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in the generation of natural killer and B cells from primitive human fetal liver progenitors. Exp Hematol. 2000;28:961–973. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00490-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bárcena A, Muench MO, Song KS, Ohkubo T, Harrison MR. Role of CD95/Fas and its ligand in the regulation of the growth of human CD34++CD38− fetal liver cells. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:1428–1439. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ. Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science. 1997;277:1669–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muench MO, Cupp J, Polakoff J, Roncarolo MG. Expression of CD33, CD38, and HLADR on CD34+ human fetal liver progenitors with a high proliferative potential. Blood. 1994;83:3170–3181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]