Abstract

Alternative splicing of the first intracellular loop differentially targets plasma membrane calcium ATPase (PMCA) isoform 2 to the apical or basolateral membrane in MDCK cells. To determine if the targeting is affected by lipid interactions, we stably expressed PMCA2w/b and PMCA2z/b in MDCK cells, and analyzed the PMCA distribution by confocal fluorescence microscopy and membrane fractionation. PMCA2w/b showed clear apical and lateral distribution, whereas PMCA2z/b was mainly localized to the basolateral membrane. A significant fraction of PMCA2w/b partitioned into low-density membranes associated with lipid rafts. Depletion of membrane cholesterol by methyl-β-cyclodextrin resulted in reduced lipid raft association and a striking loss of PMCA2w/b from the apical membrane, whereas the lateral localization of PMCA2z/b remained unchanged. Our data indicate that alternative splicing differentially affects the lipid interactions of PMCA2w/b and PMCA2z/b and that the apical localization of PMCA2w/b is lipid raft-dependent and sensitive to cholesterol depletion.

Keywords: alternative splicing, apical membrane, lipid raft, membrane targeting, plasma membrane calcium ATPase, PMCA2

Introduction

Plasma membrane calcium ATPases (PMCAs) are present in all eukaryotic cells and are responsible for the expulsion of Ca2+ from the cell interior to the extracellular environment [1]. Mammalian PMCAs are encoded by four genes yielding PMCA isoforms 1–4, and alternative RNA splicing at two sites (A and C) can generate over 20 different PMCA isoforms [2]. Splicing at site A affects the first intracellular loop of the PMCA and is especially complex in PMCA2. Exclusion of all optional exons results in splice variant 2z, whilst inclusion of all three optional exons leads to splice variant 2w (Fig. 1A). This splice occurs only in PMCA2 and leads to a pump protein with a total of 45 “extra” amino acid residues in the first intracellular loop. The functional effect of splicing at site A in the PMCAs is not clear, but recent evidence has shown that the large w-insert is important for directing PMCA2 to the apical membrane in polarized MDCK and in cochlear hair cells [3–5]. By contrast, splicing at site C affects the regulatory properties of the pumps, notably those by calmodulin [6]. The resulting splice variants, named “a” and “b”, arise from the inclusion or exclusion, respectively, of conserved exon sequences within the calmodulin-binding region [2].

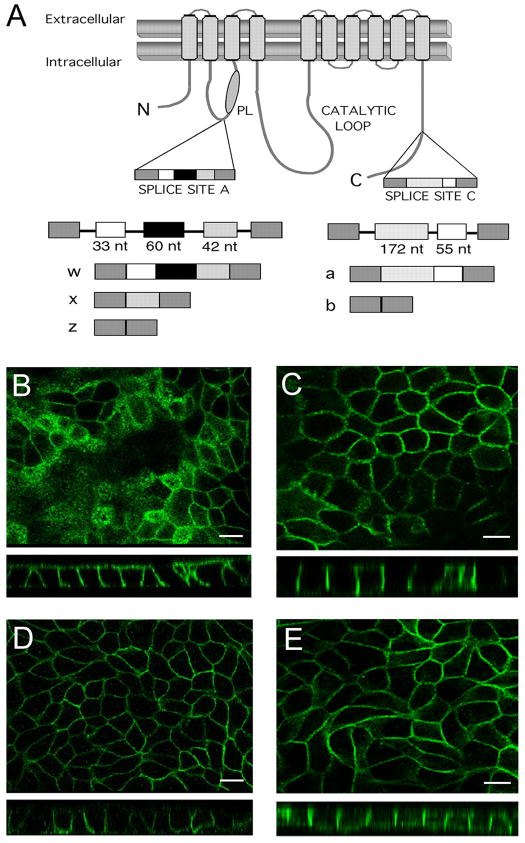

Fig. 1. Differential membrane localization of PMCA2w/b and PMCA2z/b in stably transfected MDCK cells.

(A) Scheme of PMCA2 and its major splice variants. The model on top shows the PMCA with its membrane-spanning segments indicated by gray boxes and the lipid bilayer as two horizontal bars. The two major splice sites A and C are indicated. N and C, NH2- and COOH-terminus, respectively; PL, phospholipid-sensitive region in the first intracellular loop. The alternatively spliced exons are shown as separate boxes, and their sizes in nucleotides (nt) are indicated in a scheme of the genomic organization on the bottom. The exon configuration and nomenclature of the major human PMCA2 splice variants are also shown. (B)–(E) Localization of PMCA2 in stably transfected MDCK cells expressing PMCA2w/b (B and C) or PMCA2z/b (D and E) as determined by confocal fluorescence microscopy. In (C) and (E), cells were treated with 5 μM lovastatin for 48 h followed by 50 mM MβCD for 1h to deplete membrane cholesterol. En face views are shown in the top panels and the corresponding stacked z-sections in the bottom panels. In control cells, PMCA2w/b shows predominant apical distribution in addition to basolateral staining (B). Apical localization is abolished upon cholesterol depletion and all PMCA2w/b is now present in the (baso)lateral membranes (C). By contrast, PMCA2z/b is mainly localized in the basolateral membrane in control cells (D) and this membrane distribution is not affected by cholesterol depletion (E). Scale bar = 20 μm.

PMCA2 is a major isoform in neurons where it is concentrated in specific compartments such as dendritic spines and presynaptic boutons [7, 8]. PMCA2 is also highly expressed in specialized epithelial cells such as those of lactating mammary glands [9]. In mammary and in sensory epithelial cells (e.g., cochlear hair cells), PMCA2 is highly enriched in the apical membrane and the splice type invariably corresponds to the w-form. The molecular mechanism of the apical targeting of PMCA2w is not known, as the pump does not display apical sorting elements such N- or O-glycosylation or linkage to a GPI anchor [10].

Lipid rafts are lipid-protein microdomains of the plasma membrane that are enriched in cholesterol and glycosphingolipids [11]. Lipid rafts appear to be instrumental in targeting proteins to the apical membrane and have been implicated in regulating the trafficking and clustering of membrane-associated proteins as well as their associated intracellular signaling molecules [10, 12].

To investigate the membrane partitioning of the PMCA2w/b and PMCA2z/b splice variants in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, we used stably transfected cells for biochemical fractionation and immunocytochemical localization studies. To determine if apical targeting of the PMCA2w splice form is lipid raft-dependent, we also altered the lipid composition of the membranes through cholesterol and glycosphingolipid depletion in the presence of lovastatin (an inhibitor of cholesterol synthesis) and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD). We found that apical localization of PMCA2w/b is highly sensitive to cholesterol depletion, suggesting that the targeting of PMCA2 isoforms varying in the alternatively spliced intracellular loop is dependent on their different lipid interactions.

Materials and methods

Generation of stably transfected cells and cell culture

Stably transfected MDCK cells expressing PMCA2w/b and PMCA2z/b were generated following a protocol used previously to generate MDCK cell lines expressing PMCA4b [13]. Full-length constructs for PMCA2z/b and PMCA2w/b have been described [3]. Cells were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine and antibiotics (1% penicillin and 1% streptomycin, G418 (500 μg/ml)).

Cholesterol depletion

Depletion of cholesterol from MDCK cells expressing PMCA2w/b and PMCA2z/b was performed by incubating the cells at 37°C for 48 h in complete DMEM with 5 μM lovastatin followed by 1 h in 50 mM MβCD, which is the concentration required to efficiently deplete cholesterol from this cellular system [14–16]. After the above incubation, cells were used for confocal immunostaining and sucrose floatation gradient centrifugation.

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were cultured on coverslips in 12 well culture plates seeded at 1.0 × 106 cells/well. Cells were cultured for 7 days and the medium was changed every other day until well-polarized monolayers were formed. The cells were washed in PBS plus Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline, DPBS), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, rinsed twice in DPBS and further permeabilized with 100% ice-cold methanol for 10 min at −20°C. The washed cells were then blocked in blocking buffer (DPBS containing 5% (v/v) normal goat serum and 2mg/ml bovine serum albumin) for 1 h at room temperature followed by incubation with affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-PMCA2 primary antibody NR-2 (1:500 in blocking buffer) for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with DPBS, the cells were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies coupled to Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes) diluted 1:600 in blocking buffer. After final washing, coverslips were mounted in Prolong mounting media (Molecular Probes). Confocal micrographs were taken on a Zeiss LSM510 microscope using an Apochromat 63x oil immersion objective and captured using LSM510 software version 2.8 (Zeiss). Images were imported and edited using Adobe Photoshop 5.0.

Detergent lysis and sucrose flotation gradients

Stably transfected MDCK cells expressing PMCA2w/b and PMCA2z/b were seeded on 100 mm-diameter cell culture dishes at 1×107 cells/dish and cultured for 10 days until well-polarized monolayers were formed. After rinsing with cold MBS (25 mM MES, pH 6.5, 150 mM NaCl), the cells were scraped into 2 ml cold MBS supplemented with 1% Triton X-100 and a protease inhibitor cocktail for use with mammalian cell and tissue extracts (Sigma-Aldrich). In all subsequent steps, solutions and samples were kept at 4°C. Membrane fractionation was performed as described [17–20] with some modifications. Briefly, cells were homogenized by using a loose fitting Dounce homogenizer (20 strokes) followed by 5 passages through a 21-gauge needle, and finally a bath sonicator (three 20-s bursts). The homogenates were placed at the bottom of ultracentrifuge tubes (Beckman) and brought to 40% sucrose by mixing with an equal volume of 80% sucrose (w/v) in MBS. The homogenate was then overlaid with 6 ml of 30% sucrose and 4 ml of 5% sucrose in MBS, and centrifuged at 39,000 rpm for 20 h at 4°C in a Beckman SW41 rotor. After centrifugation, twelve fractions of 1 ml each were collected from the top of the gradient. The lipid raft-containing light-scattering band just above the 5–30% sucrose interface was mainly collected in fraction 5. Gradient fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot-analysis.

Detergent-free flotation gradients

The procedure was performed as described [17, 21] with slight modifications. Briefly, polarized monolayer cells were scraped into 2 ml of 500 mM Na2CO3, pH 11.0. Homogenization was carried out as above using a loose fitting Dounce homogenizer (20 strokes), 21-gauge needle (5 passages) and a sonicator (three 20-s bursts). The homogenate was then adjusted to 40% sucrose by addition of 2 ml of 80% sucrose prepared in MBS and loaded into the bottom of ultracentrifuge tubes. A 30 to 5% discontinuous sucrose gradient was formed by overlaying 6 ml of 30% sucrose and 4 ml of 5% sucrose and centrifugation at 39,000 rpm in a Beckman SW41 rotor for 20 h at 4°C. After centrifugation, 1 ml fractions were collected from the top to the bottom and were subjected to Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis

20 μl (1:1 with 20 μl loading buffer) lipid raft gradient samples were electrophoresed on 4–12% Criterion Precast Gels (BioRad) and transferred to pure nitrocellulose membrane. Blots were blocked in TBST (20 mM Tris base, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.4) with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. Affinity-purified polyclonal anti-PMCA2 primary antibody NR-2 was diluted (1:1000) in the above blocking buffer. Secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase was purchased from Sigma and used at 1:2000 dilution in the above blocking buffer. Incubation with primary and secondary antibodies, washing, and detection of the signals was done as described previously [22]. Affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody against caveolin-1 [23], a known marker of triton-insoluble low-density lipid domains, was used to identify the fractions containing the cholesterol-enriched membranes, and was a kind gift from Dr. Mark A. McNiven (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN).

Measurement of protein and cholesterol contents

The cholesterol contents in gradient fractions were measured using the Amplex Red choleassay kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s direction. Fluorescence was measured on a Tunable microplate reader using excitation at 545 nm and emission at 570 nm. The protein concentrations of the gradient samples were determined spectrophotometrically by using the BCA™ Protein Assay Kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s procedure.

Results and discussion

Apical and basolateral distribution of PMCA2w/b and 2z/b

The localization of the PMCA2w/b and 2z/b in the stably transfected MDCK cells was assessed by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. PMCA2w/b was prominently found in the apical membrane in addition to lateral staining (Fig. 1B), whereas PMCA2z/b was mainly localized to the basolateral membrane (Fig. 1D), as best illustrated by the stacked Z-axis sections (bottom panels in Fig. 1B and 1D). This differential distribution of the w- and z-splice forms of PMCA2 corresponds to the pattern seen when these pumps are transiently expressed in polarized MDCK cells [3] and confirms earlier observations showing that the w-insert of PMCA2 is important for directing the pump to the apical membrane in inner ear hair cells [4, 5] and lactating mammary epithelial cells [9].

A fraction of PMCA2w/b is associated with lipid raft membranes

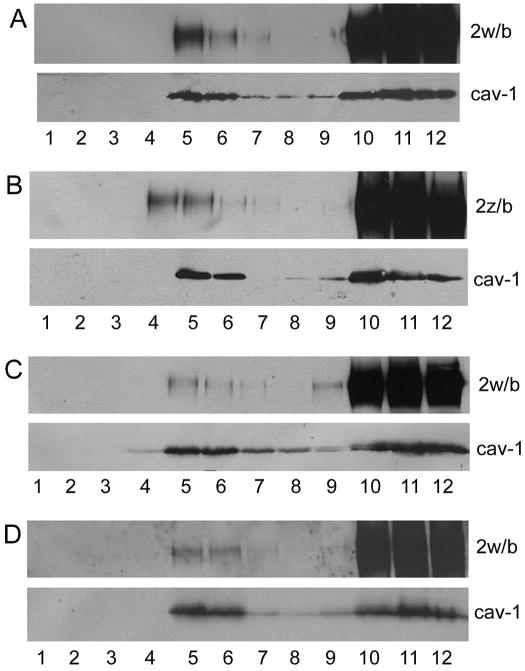

To examine whether the two PMCA2b splice variants differentially associate with cell membrane lipid rafts, PMCA2w/b- and 2z/b-expressing MDCK cells were solubilized in Triton X-100 at 4°C and rafts isolated by sucrose density gradient centrifugation followed by Western blot analysis. The results in Fig. 2A demonstrate that a significant amount of PMCA2w/b was present in the low-density fractions (fractions 5 and 6) corresponding to detergent-resistant raft membranes as determined by an enrichment in the lipid raft marker protein caveolin-1. Less PMCA2z/b appeared to be in the low-density fractions (Fig. 2B). However, for both PMCA2w/b and PMCA2z/b the majority of the pump (over 95%) was found in the high-density fractions 10–12 (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). This result is in agreement with an earlier study by Sepúlveda et al. [24] who showed that the majority of PMCA2 was in the non-raft fraction in synaptosomal membranes from pig cerebellum, but contrasts with a study by Jiang et al. [25] who reported more than 50% of the total PMCA2 in raft membranes from rat cortical neurons. Although these studies did not differentiate among the splice forms of PMCA2, they indicate that significant differences exist in the raft versus non-raft partitioning of PMCA2 depending on the tissue/cell type. To further confirm the presence of a subfraction of PMCA2w/b in lipid rafts and compare the PMCA2w/b partitioning in raft membranes isolated by different procedures, we used a detergent-free flotation gradient method that is based on sonication of the membranes under alkaline pH (see Materials and methods). Under these conditions, a similar pattern of PMCA2w/b distribution was observed as with the detergent extraction method, although the amount of PMCA2 associated with raft fractions 5 and 6 was reduced (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. PMCA2 partially associates with lipid rafts and is sensitive to cholesterol depletion.

Membranes from MDCK cells expressing PMCA2w/b and 2z/b were fractionated on sucrose gradients, and aliquots of each fraction were tested by Western blotting for the presence of PMCA2 (top panels) and the lipid raft marker caveolin-1 (bottom panels). (A) and (B) Fractionation of detergent-solubilized membranes from cells expressing PMCA2w/b and 2z/b, respectively. (C) Detergent-free membrane fractionation of cells expressing PMCA2w/b. (D) Fractionation of detergent-solubilized membranes from cholesterol-depleted cells expressing PMCA2w/b.

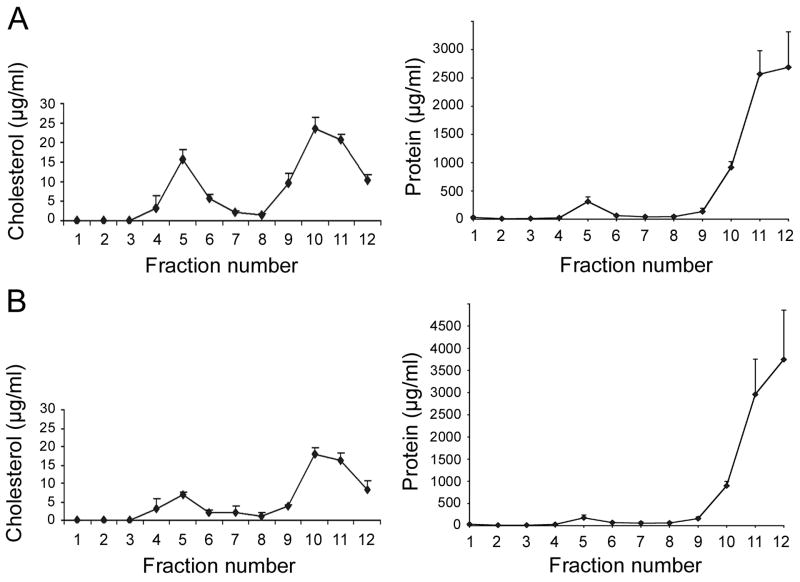

Fig. 3. Effects of cholesterol depletion on the cholesterol and protein content in membrane fractions from MDCK cells expressing PMCA2w/b.

(A) Cholesterol (left panel) and total protein contents (right panel) were determined in each sucrose gradient fraction of detergent-solubilized membranes from MDCK cells expressing PMCA2w/b. Note the high content of cholesterol relative to protein in the raft fractions 4–6. (B) Cholesterol (left panel) and total protein (right panel) content in the sucrose gradient fractions of cholesterol-depleted MDCK cells expressing PMCA2w/b. Note the pronounced decrease in cholesterol in raft fractions 4–6 compared to untreated cells. Data are presented as means + SE.

Cholesterol depletion abolishes apical membrane localization of PMCA2w/b

We determined the cholesterol and total protein concentration in each fraction of the sucrose density gradient from PMCA2w/b expressing MDCK cells. As expected, the low-density lipid raft fractions (peak in fraction 5) were highly enriched in cholesterol relative to the protein content (Fig. 3A). To investigate whether the lipid raft and apical membrane localization of PMCA2w/b was cholesterol-dependent, we treated PMCA2w/b expressing MDCK cells with lovastatin and MβCD, a drug widely used to deplete cholesterol from cell membranes. The treatment resulted in >50% reduction of the cholesterol content in the raft fractions 5 and 6 (Fig. 3B) and a concomitant decrease in the amount of PMCA2w/b in these fractions (Fig. 2D). Most strikingly, the apical localization of PMCA2w/b was completely lost and instead, all of the PMCA2w/b was now found in the basolateral membrane (Fig. 1C). By contrast, cholesterol depletion in MDCK cells expressing PMCA2z/b did not result in a relocalization of the pump, which remained basolateral as in untreated cells (Fig. 1D).

Our results suggest that differential partitioning in lipid microdomains is an important determinant of the apical versus basolateral localization of the PMCA2w and 2z splice variants. PMCA2w/b and 2z/b only differ in the size of the insert in the first intracellular loop, and this may impart an altered transmembrane conformation to the two pumps. The length and physicochemical properties of the transmembrane domain of a resident membrane protein are thought to match the lipid bilayer characteristics [26]: the specific properties of apical membranes may thus be a preferred match for the PMCA2w variant.

Recent work has shown that apical membranes are enriched in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) and that the lipid composition of the membrane is a major factor in the sorting of apical versus basolateral membrane proteins (reviewed in [27]). Interestingly, PIP2 is a known activator of the PMCA [28]; hence the preferential association of PMCA2w with PIP2-enriched membranes could ensure enhanced apical pump activity. We also note that splice site A is located in the immediate vicinity of a confirmed acidic lipid-binding region in PMCA4b (see Fig. 1A; [29–32]): it is thus likely that the w-insert in PMCA2w directly affects the lipid interaction of the pump.

Raft-associated sorting has been proposed as a mechanism for apical targeting of some membrane proteins [33]. We found that a significant fraction of PMCA2w/b partitioned into cholesterol-rich lipid raft membranes. PMCA2w/b may thus be sorted apically by virtue of its preference for raft lipids. In agreement with an earlier report that cholesterol depletion inhibits apical targeting of many membrane proteins [34], the apical localization of PMCA2w/b was abolished upon cholesterol depletion in MDCK cells. These results lend further support to the hypothesis that intrinsic differences in lipid interactions between the PMCA2w- and z-splice variants regulate their preference for the apical membrane in polarized cells. Future work will be directed at studying the differences in membrane lipid affinity among these PMCA2 splice variants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark A. McNiven for the anti-caveolin-1 antibody. This work was supported by NIH grant R01-NS51769 to EES and by Hungarian Academy of Sciences grants OTKA K49476 and ETT 042/2006 to AE.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carafoli E. Calcium pump of the plasma membrane. Physiol Rev. 1991;71:129–153. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strehler EE, Zacharias DA. Role of alternative splicing in generating isoform diversity among plasma membrane calcium pumps. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:21–50. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chicka MC, Strehler EE. Alternative splicing of the first intracellular loop of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase isoform 2 alters its membrane targeting. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18464–18470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grati M, Aggarwal N, Strehler EE, Wenthold RJ. Molecular determinants for differential membrane trafficking of PMCA1 and PMCA2 in mammalian hair cells. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2995–3007. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill JK, Williams DE, LeMasurier M, Dumont RA, Strehler EE, Gillespie PG. Splice-site A choice targets plasma-membrane Ca2+-ATPase isoform 2 to hair bundles. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6172–6180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0447-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penniston JT, Enyedi A. Modulation of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump. J Membr Biol. 1998;165:101–109. doi: 10.1007/s002329900424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stauffer TP, Guerini D, Celio MR, Carafoli E. Immunolocalization of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump isoforms in the rat brain. Brain Res. 1997;748:21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burette A, Weinberg RA. Perisynaptic organization of plasma membrane calcium pumps in cerebellar cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:1127–1135. doi: 10.1002/cne.21237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinhardt TA, Filoteo AG, Penniston JT, Horst RL. Ca2+-ATPase protein expression in mammary tissue. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C1595–C1602. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.5.C1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanzal-Bayer MF, Hancock JF. Lipid rafts and membrane traffic. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2098–2104. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simons K, Toomre D. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:31–39. doi: 10.1038/35036052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikonen E. Roles of lipid rafts in membrane transport. Curr Op Cell Biol. 2001;13:470–477. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pászty K, Antalffy G, Penheiter AR, Homolya L, Padányi R, Iliás A, Filoteo AG, Penniston JT, Enyedi Á. The caspase-3 cleavage product of the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase 4b is activated and appropriately targeted. Biochem J. 2005;391:687–692. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francis SA, Kelly JM, McCormack J, Rogers RA, Lai J, Schneeberger EE, Lynch RD. Rapid reduction of MDCK cell cholesterol by methyl-beta-cyclodextrin alters steady state transepithelial electrical resistance. Eur J Cell Biol. 1999;78:473–484. doi: 10.1016/s0171-9335(99)80074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipardi C, Nitsch L, Zurzolo C. Detergent-insoluble GPI-anchored proteins are apically sorted in Fischer rat thyroid cells, but interference with cholesterol or sphingolipids differentially affects detergent insolubility and apical sorting. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:531–542. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Röper K, Corbeil D, Huttner WB. Retention of prominin in microvilli reveals distinct cholesterol-based lipid micro-domains in the apical plasma membrane. Nature Cell Biol. 2000;2:582–592. doi: 10.1038/35023524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song SK, Li S, Okamoto T, Quilliam LA, Sargiacomo M, Lisanti MP. Co-purification and direct interaction of Ras with caveolin, an integral membrane protein of caveolae microdomains. Detergent-free purification of caveolae membranes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9690–9697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanagisawa M, Nakamura K, Taga T. Roles of lipid rafts in integrin-dependent adhesion and gp130 signalling pathway in mouse embryonic neural precursor cells. Genes to Cells. 2004;9:801–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pang S, Urquhart P, Hooper NM. N-glycans, not the GPI anchor, mediate the apical targeting of a naturally glycosylated, GPI-anchored protein in polarised epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5079–5086. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butchbach MER, Tian G, Guo H, Lin CLG. Association of excitatory amino acid transporters, especially EAAT2, with cholesterol-rich lipid raft microdomains. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34388–34396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vial C, Fung CYE, Goodall AH, Mahaut-Smith MP, Evans RJ. Differential sensitivity of human platelet P2X1 and P2Y1 receptors to disruption of lipid rafts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sgambato-Faure V, Xiong Y, Berke JD, Hyman SE, Strehler EE. The homer-1 protein Ania-3 interacts with the plasma membrane calcium pump. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:630–637. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao H, Chen J, Awoniyi M, Henley JR, McNiven MA. Dynamin 2 mediates fluid-phase micropinocytosis in epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:4167–4177. doi: 10.1242/jcs.010686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sepúlveda MR, Berrocal-Carrillo M, Gasset M, Mata AM. The plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase isoform 4 is localized in lipid rafts of cerebellum synaptic plasma membranes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:447–453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang L, Fernandes D, Mehta N, Bean JL, Michaelis ML, Zaidi A. Partitioning of the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase into lipid rafts in primary neurons: effects of cholesterol depletion. J Neurochem. 2007;102:378–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McIntosh TJ, Simons SA. Roles of bilayer material properties in function and distribution of membrane proteins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:177–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin-Belmonte F, Mostov K. Regulation of cell polarity during epithelial morphogenesis. Curr Op Cell Biol. 2008;20:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Missiaen L, Raeymaekers L, Wuytack F, Vrolix M, DeSmedt H, Casteels R. Phospholipid-protein interactions of the plasma-membrane Ca2+-transporting ATPase. Biochem J. 1989;263:287–294. doi: 10.1042/bj2630687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zvaritch E, James P, Vorherr T, Falchetto R, Modyanov N, Carafoli E. Mapping of functional domains in the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump using trypsin proteolysis. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8070–8076. doi: 10.1021/bi00487a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filoteo AG, Enyedi A, Penniston JT. The lipid-binding peptide from the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump binds calmodulin and the primary calmodulin-binding domain interacts with lipid. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11800–11805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brodin P, Falchetto R, Vorherr T, Carafoli E. Identification of two domains which mediate the binding of activating phospholipids to the plasma-membrane Ca2+ pump. Eur J Biochem. 1992;204:939–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Tezanos Pinto F, Adamo HP. Deletions in the acidic lipid-binding region of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump. A mutant with high affinity for Ca2+ resembling the acidic lipid-activated enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12784–12789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guerriero CJ, Lai Y, Weisz OA. Differential sorting and golgi export requirements for raft-associated and raft-independent apical proteins along the biosynthetic pathway. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18040–18047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802048200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prydz K, Simons K. Cholesterol depletion reduces apical transport capacity in epithelial Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Biochem J. 2001;357:11–15. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]