Abstract

Objective To assess the acceptability of pre-pandemic influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in public hospitals in Hong Kong and the effect of escalation in the World Health Organization’s alert level for an influenza pandemic.

Design Repeated cross sectional studies using self administered, anonymous questionnaires

Setting Surveys at 31 hospital departments of internal medicine, paediatrics, and emergency medicine under the Hong Kong Hospital Authority from January to March 2009 and in May 2009

Participants 2255 healthcare workers completed the questionnaires in the two studies. They were doctors, nurses, or allied health professionals working in the public hospital system.

Main outcome measures Stated willingness to accept pre-pandemic influenza vaccination (influenza A subtypes H5N1 or H1N1) and its associating factors.

Results The overall willingness to accept pre-pandemic H5N1 vaccine was only 28.4% in the first survey, conducted at WHO influenza pandemic alert phase 3. No significant changes in the level of willingness to accept pre-pandemic H5N1 vaccine were observed despite the escalation to alert phase 5. The willingness to accept pre-pandemic H1N1 vaccine was 47.9% among healthcare workers when the WHO alert level was at phase 5. The most common reasons for an intention to accept were “wish to be protected” and “following health authority’s advice.” The major barriers identified were fear of side effects and doubts about efficacy. More than half of the respondents thought nurses should be the first priority group to receive the vaccines. The strongest positive associating factors were history of seasonal influenza vaccination and perceived risk of contracting the infection.

Conclusions The willingness to accept pre-pandemic influenza vaccination was low, and no significant effect was observed with the change in WHO alert level. Further studies are required to elucidate the root cause of the low intention to accept pre-pandemic vaccination.

Introduction

In 2005 the World Health Organization recommended its member states to revise or construct a preparedness plan for pandemic influenza. The WHO also set up a system of influenza pandemic alert levels. Phases 1-3 include capacity development and response planning, while phases 4-6 signify the need for response and mitigation efforts.1 By August 2008, 47 countries had prepared such a plan.2 The recent spread of infection with a novel influenza A virus (H1N1 subtype) of swine origin (“swine flu”) has prompted governments to review and carry out their pandemic responses, including vaccination strategies.

Modelling studies have shown that vaccination is an effective measure to reduce infection, hospitalisation, mortality and morbidity.3 Since the supply of vaccines will be limited at the beginning of the influenza pandemic, prioritisation in the administration of the vaccines has been one of the major components in pandemic preparedness. Governments in different countries have issued consultation documents outlining their proposed vaccination policies.4 5 In nearly all countries with a preparedness plan, healthcare workers are listed as the priority group for mass vaccination.6 7

The American College of Physicians position statement supports measures to increase the supply of influenza vaccine and antiviral drugs in the strategic national stockpile.8 Pre-pandemic H5N1 vaccine is now ready and stockpiled by many countries. The first batch of H1N1 vaccine is expected to be available by the end of 2009 or early 2010.9 More than 30 governments have placed their orders.9 For example, Hong Kong has decided to buy five million doses for its population of seven million, and the UK Department of Health has ordered 130 million doses of vaccine for its population of 61 million. However, healthcare workers’ acceptance of the H5N1 and H1N1 vaccines is unknown. A survey conducted in May, when the pandemic level was already at phase 5, revealed that the general public in Hong Kong did not perceive swine flu (H1N1 influenza) as a threatening disease and did not think an outbreak to be highly likely.10

The uptake of pre-pandemic vaccination among healthcare workers is a concern as the uptake of seasonal influenza vaccine is often low. In most studies, fewer than 60% of healthcare workers were vaccinated against seasonal influenza in various clinical settings. The most common barriers were fear of side effects, uncertainty about the vaccine’s efficacy, and misconceptions about the vaccination and the infection.11 12 13 14 15

One study in the UK of 520 participants found that 57.7% of healthcare workers expressed willingness to accept vaccination with the stockpiled H5N1 vaccine. Willingness was associated with perceived risk and benefits, and previous seasonal vaccination.16

The aim of our study was to investigate the stated acceptability of pre-pandemic vaccination (H5N1 or H1N1 vaccine) and its associated factors among public hospital based healthcare workers in the departments of accident and emergency medicine, internal medicine, and paediatrics in Hong Kong. We also investigated the effect of escalation of the WHO pandemic influenza alert level on the acceptability of pre-pandemic vaccination.

Methods

The first survey was conducted from January 2009 to March 2009. The WHO influenza pandemic alert level assigned to H5N1 during that period was phase 3. Phase 3 signifies an animal or human-animal influenza reassortant virus that has caused sporadic cases or small clusters of disease in people but has not resulted in human to human transmission sufficient to sustain community level outbreaks. Limited human to human transmission may occur under some circumstances, such as when there is close contact between an infected person and an unprotected carer. However, limited transmission under such restricted circumstances does not indicate that the virus has gained the level of transmissibility among humans necessary to cause a pandemic.

We recruited healthcare workers only in public hospitals in this study because 94% of secondary and tertiary healthcare services in Hong Kong are provided by these hospitals. Pandemic influenza patients will be primarily treated in these hospitals—as occurred in the outbreak of SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), when public healthcare workers were at the highest risk for contracting infection.

All department heads (42 departments with 8508 doctors and nurses) of emergency medicine, internal medicine, and paediatrics units under the Hong Kong Hospital Authority were contacted through emails, invitation letters, or telephone calls to obtain approval to send the questionnaires to their staff. These departments were chosen as their staff are at the highest risk of exposure to patients with influenza. We also sent invitation letters to the physiotherapy and occupational therapy departments under the Hospital Authority.

Self administered, anonymous questionnaires were used in both surveys. The questionnaire consisted of five sections with 17 questions: (1) demographics, patient contact, and history of seasonal influenza vaccination in 2008-9; (2) willingness to accept pre-pandemic vaccination with H5N1 vaccine; (3) willingness to accept pandemic vaccination with H1N1 vaccine (the second survey only); (4) perception of risk and seriousness of the pandemic influenza; and (5) suggestions on deployment of duties during pandemic flu, opinion on mandatory vaccination, and the possible ways of disposal for nearly expired vaccines. The participants were requested to send the completed questionnaires via internal mail.

The second survey was conducted in May 2009 when the WHO pandemic influenza alert level assigned to H1N1 influenza (swine flu) was phase 5. Phase 5 signifies human to human spread of the virus into at least two countries within one WHO region. Although most countries are not affected at this stage, the declaration of phase 5 is a strong signal that a pandemic is imminent and that the time to finalise the organisation, communication, and implementation of the planned mitigation measures is short.1 During this phase 5 period, we repeated our questionnaires in the three specialties in one hospital. All questionnaires were collected within two weeks, before the announcement of phase 6 by the WHO.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed. Using cross tabulations, we analysed univariate associations between intention to accept vaccine and the following variables: sex, age (≤30 v >30 years), specialty, job title, years working in health services, work site, weekly number of contacts with patients, whether the respondents had seasonal flu vaccination in 2008-9, how likely they thought they were to get flu if there was a pandemic, and how seriously they thought a pandemic would affect their lives. We tested the statistical significance of the associations using Pearson’s χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, or trend tests where appropriate. Trend tests were used to test associations between one binary and one ordinal variable, and for two ordinal variables if a trend was apparent in the data. Multiple logistic regression was used to evaluate independent predictors of intention to accept vaccine. Demographic variables and variables on vaccination history and attitudes were tried in the models. A flexible modelling approach was adopted, and variables were retained in the model if they had P<0.1.

We compared the results in the second survey with the results from the same hospital in the first survey to assess the effect of escalation in pandemic alert level on the willingness to accept vaccination. Differences in characteristics between the two surveys were evaluated using Fisher’s exact test.

Results

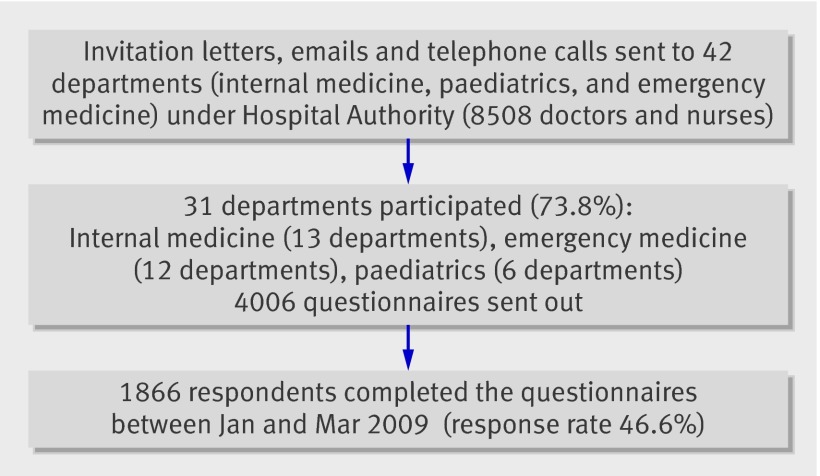

Of the 4006 questionnaires distributed for the first survey, 1866 were completed and returned, giving a response rate of 46.6%. Of the 42 targeted units, 31 (73.8%) participated (including emergency medicine, internal medicine, and paediatrics units), representing 20% of all doctors and nurses working in these units in Hong Kong. Each geographical cluster had participating hospitals, and each hospital had at least one participating department. The number of paediatrics departments participating were significantly less than the other two specialties. Details of the response to the first survey are shown in figure 1. Nurses accounted for 71.1% of the respondents, and doctors accounted for 19.3%. The distribution of the doctors and nurses was not significantly different from the overall distribution of the human resources in these units. Most (75%) of the respondents were women, because of female dominance in the nursing profession.

Fig 1 Response rate to first questionnaire survey of healthcare workers in Hong Kong hospital departments

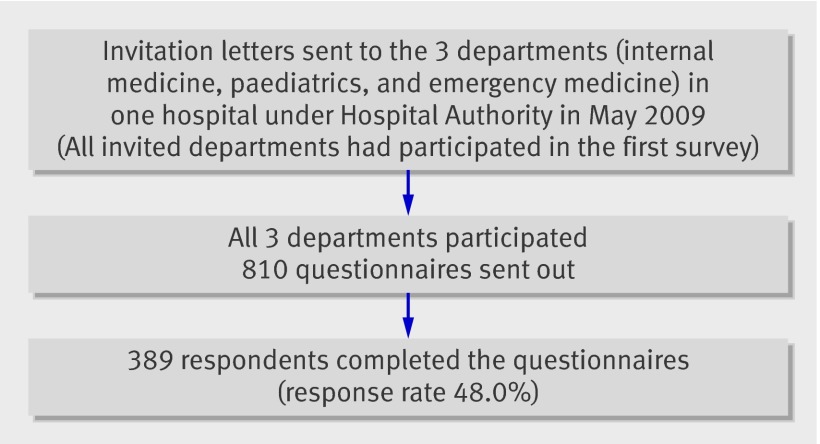

Of the 810 questionnaires distributed in the second survey, 389 were completed and returned. The response rate was 48.0%. Details of the second survey are shown in figure 2. All three invited departments had also participated in the first survey. The age and sex distribution of respondents were similar to those of the respondents in the same hospital in the first survey. Demographics of all respondents in both surveys are shown in table 1.

Fig 2 Response rate to second questionnaire survey of healthcare workers in Hong Kong hospital departments

Table 1.

Characteristics of the respondents. Values are numbers (percentages) of respondents

| Characteristic | First survey | Second survey |

|---|---|---|

| Sex: | ||

| Men | 467 (25) | 71 (18.3) |

| Women | 1399 (75) | 318 (81.8) |

| Age (years): | ||

| ≤30 | 595 (35.9) | 118 (40.1) |

| >30 | 1061 (64.1) | 176 (59.9) |

| Department: | ||

| Internal medicine | 1008 (54.1) | 200 (51.2) |

| Accident and emergency | 227 (12.2) | 23 (5.9) |

| Paediatrics | 415 (22.3) | 162 (41.3) |

| Government outpatient clinic | 3 (0.2) | 6 (1.5) |

| Physiotherapy | 99 (5.3) | — |

| Occupational therapy | 19 (1) | — |

| Non-clinical | 4 (0.2) | — |

| Administration | 3 (0.2) | — |

| Others | 85 (4.6) | — |

| Work site: | ||

| Private | 17 (0.9) | 6 (1.5) |

| Public | 1846 (99.1) | 384 (98.5) |

| Job title: | ||

| Doctor | 361 (19.3) | 47 (12.1) |

| Allied health | 125 (6.7) | 4 (1.0) |

| Nurse | 1338 (71.7) | 307 (78.9) |

| Administration | 15 (0.8) | 6 (1.5) |

| Other | 28 (1.5) | 25 (6.4) |

| Years of work in health services: | ||

| ≤5 | 416 (22.3) | 82 (21.1) |

| 6-10 | 404 (21.7) | 94 (24.2) |

| 11-20 | 714 (38.3) | 152 (39.2) |

| >20 | 332 (17.8) | 60 (15.5) |

| No of patient contacts per week: | ||

| 0 | 36 (1.9) | 12 (3.1) |

| 1-25 | 265 (14.3) | 57 (14.6) |

| 26-50 | 443 (24) | 95 (24.3) |

| >50 | 1103 (59.7) | 227 (58.1) |

| Seasonal flu vaccination in 2008-9: | ||

| Yes | 612 (32.9) | 120 (30.7) |

| No | 1251 (67.1) | 271 (69.3) |

The overall intention to accept pre-pandemic vaccination (H5N1 vaccine) was only 28.4% for the first survey, which was conducted at WHO influenza pandemic alert phase 3. The level of intention to accept increased to 34.8% in the second survey, when the WHO alert phase was level 5. Responses from three departments in the hospital where both surveys were conducted are shown in table 2. No significant changes in the level of intention to accept pre-pandemic vaccination (H5N1 vaccine) was observed, despite the escalation to phase 5 because of the wide spread of H1N1 virus (swine flu).

Table 2.

Comparison of the intention to accept vaccination with H5N1 vaccine in one hospital at two different WHO influenza pandemic alert phases

| Intention to accept vaccination | No (%) of respondents | Relative risk (95% confidence interval) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First survey (alert phase 3) | Second survey (alert phase 5) | |||

| Yes | 137 (31.2) | 134 (34.8) | 1.12 (0.92 to 1.36) | 0.30 |

| No | 302 (68.8) | 251 (65.2) | ||

The proportion of healthcare workers intending to accept pre-pandemic vaccination (H1N1 vaccine) was 47.9% when the WHO alert level was at phase 5. The respondents who were willing to accept H5N1 vaccines were more likely to accept H1N1 vaccines as well (91%); in contrast only 23.6% of those who declined H5N1 vaccination expressed an intention to accept H1N1 vaccination (P<0.0001).

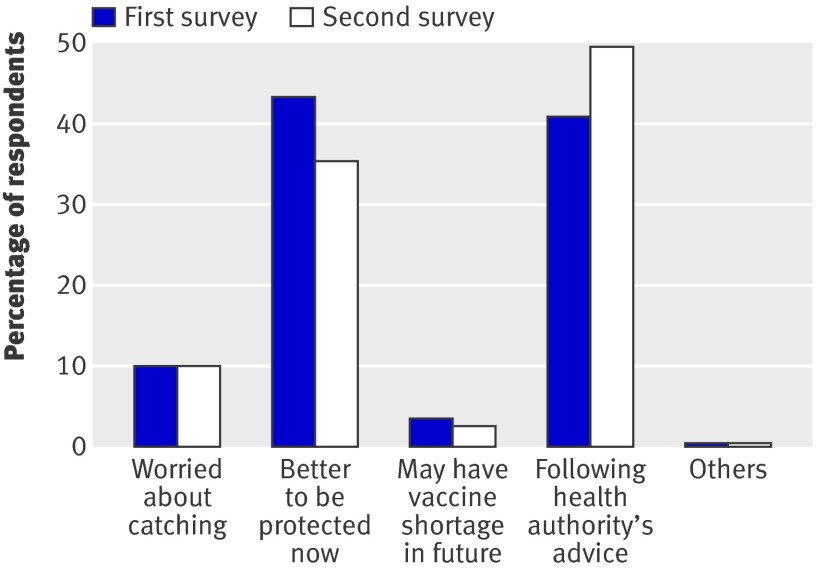

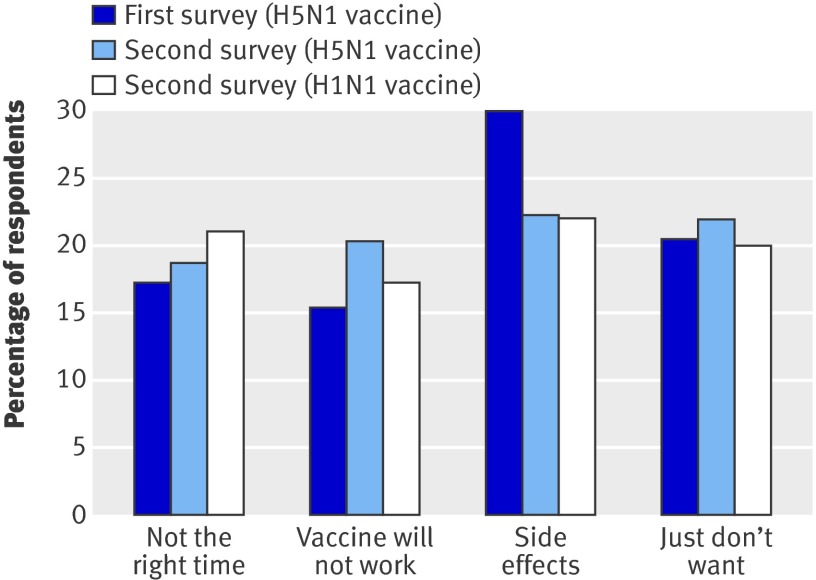

The most common reasons for intending to accept vaccination were “wish to be protected” and “following Health Authority’s advice” (fig 3). The most common reason for refusal was “worry about side effects,” and other reasons included “query on the efficacy of the vaccine,” “not yet the right time to be vaccinated,” and “simply did not want the vaccine” (fig 4). More than half of the respondents thought that nurses should be the first priority group to receive the vaccines, followed by doctors and allied health professions, and then similar ratings for non-clinical and administrative staff. About half of the respondents (52.2% in the first survey and 56.0% in the second) wanted their family members to receive the vaccines as well. All the above responses remained constant in the different WHO alert phase levels.

Fig 3 Reasons of healthcare workers in Hong Kong hospital departments for intention to accept pre-pandemic influenza vaccination

Fig 4 Reasons of healthcare workers in Hong Kong hospital departments for intention to decline pre-pandemic influenza vaccination

Univariate associations between intention to accept H5N1 vaccination and other variables at WHO alert phase 3 are shown in table 3. Male sex, working in a specialty other than internal medicine, being a doctor, having fewer years of work in the health services, having received seasonal influenza vaccination in 2008-9, and perceptions that they were likely to contract the influenza and that a pandemic would seriously affect their lives were all significantly associated with greater intention to accept vaccination. In multiple logistic regression models for intention to accept vaccination (table 4), all of these variables remained significant except for specialty, which became marginally significant.

Table 3.

Univariate association of variables affecting the intention to accept pre-pandemic influenza vaccination in the first survey of Hong Kong healthcare workers (phase 3 of WHO influenza pandemic alert). Values are numbers (percentages) of respondents unless stated otherwise

| Variable | Total | Intention to accept vaccination | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P value of difference* | ||

| Sex: | ||||

| Men | 467 (25) | 164 (36) | 291 (64) | 0.0003 |

| Women | 1399 (75) | 366 (27.2) | 982 (72.8) | |

| Hospital department: | ||||

| Medical | 1008 (54.1) | 256 (26.3) | 718 (73.7) | 0.014 |

| Accident and emergency | 227 (12.2) | 82 (37.3) | 138 (62.7) | |

| Paediatrics | 415 (22.3) | 125(31.2) | 276(68.8) | |

| General outpatient clinic | 3 (0.2) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Physiotherapy | 99 (5.3) | 28 (28.9) | 69 (71.1) | |

| Occupational therapy | 19 (1) | 4 (23.5) | 13 (76.5) | |

| Non-clinical | 4 (0.2) | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | |

| Administration | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | |

| Others | 85 (4.6) | 30 (37) | 51 (63) | |

| Work site: | ||||

| Private | 17 (0.9) | 2 (14.3) | 12 (85.7) | 0.26 |

| Public | 1846 (99.1) | 529 (29.6) | 1258 (70.4) | |

| Job title: | ||||

| Doctor | 361 (19.3) | 166 (47.3) | 185 (52.7) | <0.0001 |

| Allied health | 125 (6.7) | 36 (29.3) | 87 (70.7) | |

| Nurse | 1338 (71.7) | 323 (25) | 969 (75) | |

| Administration | 15 (0.8) | 1 (8.3) | 11 (91.7) | |

| Other | 28 (1.5) | 4 (15.4) | 22 (84.6) | |

| Years of work in health services: | ||||

| ≤5 | 416 (22.3) | 148 (36.1) | 262 (63.9) | 0.001 |

| 6-10 | 404 (21.7) | 113(28.6) | 282 (71.4) | |

| 11-20 | 714 (38.3) | 194 (28.4) | 489 (71.6) | |

| >20 | 332 (17.8) | 76 (24.1) | 239 (75.9) | |

| No of patient contacts per week: | ||||

| 0 | 36 (1.9) | 9 (26.5) | 25 (73.5) | 0.14 |

| 1-25 | 265 (14.3) | 65 (25.6) | 189 (74.4) | |

| 26-50 | 443 (24) | 125 (29.3) | 301 (70.7) | |

| >50 | 1103 (59.7) | 326 (30.4) | 745 (69.6) | |

| Seasonal influenza vaccination in 2008-9: | ||||

| Yes | 612 (32.9) | 303 (50.9) | 292 (49.1) | <0.0001 |

| No | 1251 (67.1) | 228 (18.9) | 979 (81.1) | |

| Perceived risk of contracting pandemic flu: | ||||

| Very likely | 225 (12.2) | 75 (35) | 139 (65) | <0.0001 |

| Likely | 1115 (60.3) | 357 (32.9) | 727 (67.1) | |

| Unlikely | 470 (25.4) | 90 (19.9) | 362 (80.1) | |

| Very unlikely | 38 (2.1) | 8 (21.1) | 30 (78.9) | |

| Perceived severity of effect of flu to own life: | ||||

| Very serious | 362 (19.6) | 133 (38.1) | 216 (61.9) | <0.0001 |

| Serious | 980 (53) | 291 (30.8) | 655(69.2) | |

| Little serious | 476 (25.7) | 101 (21.9) | 360 (78.1) | |

| Not serious | 32 (1.7) | 5 (15.6) | 27 (84.4) | |

*χ2 test.

Table 4.

Multiple logistic regression model for intention to accept pre-pandemic influenza vaccination (H5N1 vaccine) in the first and second surveys of Hong Kong healthcare workers (at phases 3 and 5 of WHO influenza pandemic alert)

| Variable | Phase 3 | Phase 5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age (years): | |||||

| ≥30* | 1 | 0.17 | 1 | 0.053 | |

| <30 | 0.76 (0.52 to1.11) | 1.72 (0.99 to 3.03) | |||

| Job title: | |||||

| Doctor* | 1 | <0.0001 | 1 | 0.81 | |

| Nurse | 0.51 (0.38 to 0.68) | 0.76 (0.33 to 1.74) | |||

| Other | 0.13 (0.03 to 0.59) | 0.80 (0.22 to 2.91) | |||

| Department: | |||||

| Internal medicine* | 1 | 0.056 | 1 | 0.090 | |

| Paediatrics | 1.34 (0.98 to 1.83) | 0.61 (0.33 to 1.12) | |||

| Emergency medicine | 1.69 (1.16 to 2.46) | 1.80 (0.61 to 5.33) | |||

| No of patient contacts per week: | |||||

| ≤25* | 1 | 0.079 | |||

| 26-50 | 1.56 (0.62 to 3.93) | ||||

| >50 | 2.40 (1.07 to 5.40) | ||||

| Years of work in health services: | |||||

| ≤5* | |||||

| 6-10 | 0.78 (0.53 to 1.16) | 0.012 | |||

| 11-20 | 0.56 (0.36 to 0.88) | ||||

| >20 | 0.42 (0.25 to 0.73) | ||||

| Seasonal influenza vaccination in 2008-9: | |||||

| No* | 1 | <0.0001 | 1 | <0.0001 | |

| Yes | 4.00 (3.13 to 5.12) | 7.43 (4.20 to 13.16) | |||

| Perceived risk in contracting pandemic flu: | |||||

| Very unlikely/unlikely* | 1 | 0.012 | 1 | 0.16 | |

| Likely | 1.40 (0.52 to 3.78) | 2.15 (0.95 to 4.89) | |||

| Very likely | 1.20 (0.43 to 3.40) | 1.26 (0.63 to 2.52) | |||

| Perceived severity of effect of flu to own life: | |||||

| Not serious* | 1 | 0.015 | |||

| Little serious | 0.93 (0.32 to 2.72) | ||||

| Serious | 1.33 (0.46 to 3.79) | ||||

| Very serious | 1.70 (0.58 to 4.94) | ||||

*Reference variable.

At WHO alert phase 5, only having received seasonal influenza vaccination in 2008-9 and younger age were found as significant associated factors for intention to accept H5N1 vaccination in multiple logistic regression (table 4).

For H1N1 vaccination, the factors showing a significant association with intention to accept at WHO alert phase 5 after adjustment by multiple logistic regression included younger age; having received seasonal influenza vaccination in 2008-9, and the perception that they were more likely to contract the pandemic influenza. The results are shown in table 5.

Table 5.

Multiple logistic regression model for intention to accept pandemic influenza vaccination (H1N1 vaccine) in the second survey of Hong Kong healthcare workers (at phase 5 of WHO influenza pandemic alert)

| Variables | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years): | ||

| ≥30* | 1 | 0.034 |

| <30 | 2.44 (1.08 to 5.56) | |

| Job title: | ||

| Doctor* | 1 | 0.084 |

| Nurse | 0.54 (0.23 to 1.23) | |

| Other | 1.51 (0.40 to 5.63) | |

| No of patient contacts per week: | ||

| ≤25* | 1 | 0.53 |

| 26-50 | 1.64 (0.70 to 3.82) | |

| >50 | 1.35 (0.64 to 2.88) | |

| Years of work in health services: | ||

| ≤5* | 1 | 0.35 |

| 6-10 | 0.69 (0.29 to 1.63) | |

| 11-20 | 0.98 (0.35 to 2.73) | |

| >20 | 0.52 (0.16 to 1.68) | |

| Seasonal influenza vaccination in 2008-9: | ||

| No* | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 4.40 (2.42 to 8.00) | |

| Perceived risk in contracting pandemic flu: | ||

| Very unlikely/unlikely* | 1 | 0.005 |

| Likely | 4.36 (1.76 to10.80) | |

| Very likely | 2.21 (1.12 to 4.34) | |

| Perceived severity of effect of flu to own life: | ||

| Not serious/little serious* | 1 | 0.14 |

| Serious | 1.02 (0.41 to 2.51) | |

| Very serious | 1.73 (0.98 to 3.08) |

*Reference variable.

Discussion

The surveys conducted at WHO pandemic alert phases 3 and 5 found a consistently low level of willingness to accept pre-pandemic influenza vaccination among hospital based healthcare workers, especially in those working in the allied health professions. This is particularly surprising in a city where the SARS outbreak had such a huge impact. The intention to accept vaccination against H1N1 influenza (swine flu) in our study was less than 50% even at WHO alert phase 5. On 21 May 2009, the WHO stated that 41 countries had officially reported 11 034 cases of swine flu, including 85 deaths.17 This was the time when our survey was conducted. It was surprising that neither this information nor the escalated WHO alert phase affected the intention to accept pre-pandemic vaccination. Vaccination is one of the potentially effective measures that can reduce mortality and morbidity from pandemic influenza. On 13 July 2009, the WHO also recommended that all countries should immunise their healthcare workers as a first priority to protect the essential health infrastructure.18 However, the effectiveness of this measure depends heavily on the uptake rate in those groups assigned high priority. Therefore, the low potential acceptance of this vaccine warrants our attention, with a view to improving acceptance.

Health belief model

The factors with the strongest association with intention to accept pre-pandemic or pandemic vaccine were history of seasonal influenza vaccination and perceived risk of contracting the infection. The strong association between acceptance of seasonal and pre-pandemic vaccination also suggests similar barriers exist for both vaccines. Efforts to improve the uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination by healthcare workers should therefore be a part of the pandemic preparedness plan, as disseminating correct information may be more difficult at time of crisis, and the health belief model could be applied to improve the acceptance of pre-pandemic vaccine as in seasonal influenza vaccination.19

The major barriers to vaccination we identified were fear of side effects and questions about its efficacy. This suggests that public and hospital health agencies need to provide more information to staff, especially to those with higher levels of anxiety and doubt.

In our study younger staff and staff whose working experience was less than five years were more willing to accept vaccination. This again implies that the experience of the SARS outbreak did not enhance the willingness to accept the vaccination.

Comparison with another study

The willingness of Hong Kong healthcare workers to be vaccinated against H5N1 virus is very low when compared with the study done in a UK NHS trust, where more than half of the staff were willing to accept pre-pandemic vaccination when surveyed at a similar WHO alert level (phase 3).16 The uptake rates for seasonal influenza vaccine were higher among our participants than in the UK study (32.9% for Hong Kong and 15.6% for UK healthcare workers), whereas the proportion willing to be vaccinated against H5N1 influenza in the UK study (57.7%) was double that in our survey (28.4%). Whether this higher willingness to accept was only temporary as a result of the well publicised H5N1 outbreak at a poultry farm in the UK when the survey was started remains to be explored.

Seasonal influenza vaccine uptake

The uptake rate for seasonal influenza vaccine in Hong Kong varies among the target groups. A previous study on patients attending a general outpatient clinic, of whom half had chronic illnesses, found a vaccination rate of 27%, but without correlation with sex, occupation, or household income.20 The uptake rate among elderly people aged >65 years living in the community was also low (26.9-36.4%).21 In contrast, more than 90% of elderly people living in institutions received influenza vaccine, which was delivered on site.22 The overall vaccination rate for elderly people in Hong Kong could be within the range reported from surveys in the UK, Italy, France, Germany, and Spain conducted from 2003 to 2007 (41.3-78.1%).23 As for healthcare workers, both Hong Kong and European countries face a low uptake rate. The 32.9% vaccination recorded in the current study is close to the ranges reported for the UK (15.9-25.2%), Italy (13.3-23.2%), Spain (20.5-28.9%), Germany (22.0-27.5%), and France (15.8-22.2%).23

The Department of Health in Hong Kong provides a comprehensive immunisation programme from birth to 12 years old. There seems to be no major generic barrier to vaccination in Hong Kong, as the uptake for childhood immunisation programmes is high (84.7-99.6%),24 and a recent survey indicates a high level of willingness (88%) to accept human papillomavirus vaccine,25 similar to that recorded in the UK (89%).26

While cultural differences could affect the acceptance of vaccines in general, we believe there are common barriers to influenza vaccination that exist across geographical regions and racial groups.27 The findings of this study can therefore serve as a reference for other countries that are planning to offer the H1N1 vaccine to their healthcare workers.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

To our knowledge, this is the largest study conducted to assess the willingness of healthcare workers to accept pre-pandemic influenza vaccination, and it provides important information on barriers to vaccination. Campaigns to promote vaccination should consider addressing the knowledge gap of staff and the specific target groups for intervention. Our study also captured the effects of change in WHO alert level on people’s perception and willingness to accept vaccination.

The main limitation of this study is the response rate of below 50%. The low response rate may have resulted in a biased sample. Another caveat is the lack of details for the non-responders. Nevertheless, the characteristics of the participants matched the overall staff profile, and the participating specialty departments represented over 70% of our target population. An additional limitation is that the study only documented what people said they would do and thus may not reflect the actual vaccine uptake rates. A follow-up study will be needed to capture the true uptake rates and factors associated with vaccine uptake when it is available. Further qualitative studies such as focus group discussion or semi-structured interviews could help to consolidate and supplement the findings.

Conclusions and policy implications

We believe this information can assist governments to design their pandemic vaccination plan for healthcare workers, taking into account their opinions on these contentious issues. A successful vaccination strategy does not just protect the health of healthcare workers but also can limit the transmission between the health sector and the community, a lesson from the SARS outbreak. Qualitative studies are being conducted by our group to explore barriers faced by healthcare workers in the uptake of vaccination. With the reported low level of willingness to accept pre-pandemic vaccination in this study, future work on intervention to increase vaccination uptake is warranted.

What is already known on this topic

The WHO recommended that healthcare workers in all countries should get top priority for vaccination against the influenza A H1N1 virus of swine origin

The acceptance of seasonal influenza vaccination in healthcare workers worldwide is low. One study conducted at WHO alert phase 3 showed 57.7% of UK healthcare workers would accept the pre-pandemic H5N1 vaccine

What this study adds

The willingness to accept vaccination against both influenza A subtypes H5N1 and H1N1 among hospital based healthcare workers in Hong Kong was low

Neither the change in WHO pandemic alert levels nor the experience of the SARS outbreak affected the potential acceptance of the vaccines

Barriers identified include fear of side effects and doubts about the efficacy of the vaccines

The strongest associations with the intention to accept vaccination were a history of seasonal influenza vaccination and perceived likelihood of being infected

We thank Dr Ian Stepheson for his invaluable advice and experience in constructing the questionnaires and generous support from the chiefs of service in the participating departments. We also thank Ms Kate TC Ng for organising the questionnaire administration.

Contributors: JSY Chor and PKS Chan designed the study, interpreted the findings, and wrote the manuscript; KLK Ngai collated the survey data; WB Goggins and SYS Wong performed statistical analyses; MCS Wong, N Lee, TF Leung, TH Rainer administered the survey; S Griffiths supervised the study. All authors, external and internal, had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This study did not receive any external funding.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Data sharing: no additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b3391

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global alert and response (GAR). Current WHO phase of pandemic alert. www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/phase/en/index.html.

- 2.Jennings LC, Monto AS, Chan PK, Szucs TD, Nicholson KG. Stockpiling prepandemic influenza vaccines: a new cornerstone of pandemic preparedness plans. Lancet Infect Dis 2008;8:650-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nuno M, Chowell G, Gumel AB. Assessing the role of basic control measures, antivirals and vaccine in curtailing pandemic influenza: scenarios for the US, UK and the Netherlands. J R Soc Interface 2007;4:505-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Technical report. Expert advisory groups on human H5N1 vaccines. 2007.

- 5.Ministry of Health NZ. H5N1 pre-pandemic vaccine consultation document. 2007. www.moh.govt.nz.

- 6.Traynor K. United States issues draft guidance for pandemic flu vaccination. Am J Health-System Pharmacy 2007;64:2412-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Straetemans M, Buchholz U, Reiter S, Haas W, Krause G. Prioritization strategies for pandemic influenza vaccine in 27 countries of the European Union and the Global Health Security Action Group: a review. BMC Public Health 2007;7:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Physicians. The health care response to pandemic influenza. Ann Int Med 2006;145:135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.msnbc. First batch of swine flu vaccine produced. 2009. www.msnbc.msn.com/id/31269066/ns/health-swine_flu/.

- 10.Lau JT, Griffiths S, Choi KC, Tsui HY. Are the public prepared for H1N1? Community responsiveness from day 7 to 9 since the identification of the first confirmed case. J Infect Dis (in press).

- 11.Christini AB, Shutt KA, Byers KE. Influenza vaccination rates and motivators among healthcare worker groups. Infect Control Hosp Epidem 2007;28:171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollmeyer H, Hayden F, Poland G, Buchholz U. Influenza vaccination of health care workers in hospital - A review of studies on attitudes and predictors. Vaccine (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Qureshi AM, Hughes NJ, Murphy E, Primrose WR. Factors influencing uptake of influenza vaccination among hospital-based health care workers. Occupational Medicine (Oxford) 2004;54:197-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van den Dool C, Van Strien AM, den Akker IL, Bonten MJ, Sanders EA, Hak E. Attitude of Dutch hospital personnel towards influenza vaccination. Vaccine 2008;26:1297-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opstelten W, van Essen GA, Ballieux MJ, Goudswaard AN. Influenza immunization of Dutch general practitioners: vaccination rate and attitudes towards vaccination. Vaccine 2008;26:5918-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pareek M, Clark T, Dillon H, Kumar R, Stephenson I. Willingness of healthcare workers to accept voluntary stockpiled H5N1 vaccine in advance of pandemic activity. Vaccine 2009;27:1242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Global alert and response (GAR). Influenza A(H1N1)—update 35. www.who.int/csr/don/2009_05_21/en/.

- 18.World Health Organization. Global alert and response (GAR). WHO recommendations on pandemic (H1N1) 2009 vaccines. www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/notes/h1n1_vaccine_20090713/en/.

- 19.Goldstein AO, Kincade JE, Gamble G, Bearman RS. Policies and practices for improving influenza immunization rates among healthcare workers. Infect Control Hospital Epidem 2004;25:908-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mok E, Yeung SH, Chan MF. Prevalence of influenza vaccination and correlates of intention to be vaccinated among Hong Kong Chinese. Public Health Nursing 2006;23:506-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau JT, Kim JH, Choi KC, Tsui HY, Yang X. Changes in prevalence of influenza vaccination and strength of association of factors predicting influenza vaccination over time-Results of two population-based surveys. Vaccine 2007;25:8279-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health Hong Kong SAR. Communicable Diseases Watch. 2005;2:101. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blank PR, Schwenkglenks M, Szucs TD. Influenza vaccination coverage rates in five European countries during season 2006/07 and trends over six consecutive seasons. BMC Public Health 2008;8:272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leung CW. Immunization. HK J Paediatr 1999;4:59-62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwan TT, Chan KK, Yip AM, Tam KF, Cheung AN, Lo SS, et al. Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccination among Chinese women: Concerns and implications: BJOG 2009:116:501-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Marlow LA, Waller J, Evans RE, Wardle J, Marlow LAV, Waller J, et al. Predictors of interest in HPV vaccination: A study of British adolescents. Vaccine 2009;27:2483-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz KL, Neale AV, Northrup J, Monsur J, Patel DA, Tobar Jr R, et al. Racial similarities in response to standardized offer of influenza vaccination: A MetroNet study. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:346-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]