Abstract

Cholecystocolonic fistula (CF) is an uncommon type of internal biliary-enteric fistulas, which comprise rare complications of cholelithiasis and acute cholecystitis, with a prevalence of about 2% of all biliary tree diseases. We report a case of a spontaneous CF in a 75-year-old diabetic male admitted to hospital for the investigation of chronic watery diarrhea and weight loss. Massive pneumobilia demonstrated on abdominal ultrasound and computerized tomography, along with chronic, bile acid-induced diarrhea and a prolonged prothrombin time due to vitamin K malabsorption, led to the clinical suspicion of the fistula. Despite further investigation with barium enema and magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography, diagnosis of the fistulous tract between the gallbladder and the hepatic flexure of the colon could not be established preoperatively. Open cholecystectomy with fistula resection and exploration of the common bile duct was the preferred treatment of choice, resulting in an excellent postoperative clinical course. The incidence of biliary-enteric fistulas is expected to increase due to the parallel increase of iatrogenic interventions to the biliary tree with the use of endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography and the increased rate of cholecystectomies performed. Taking into account that advanced imaging techniques fail to demonstrate the fistulas tract in half of the cases, and that CFs usually present with non-specific symptoms, our report could assist physicians to keep a high index of clinical suspicion for an early and valid diagnosis of a CF.

Keywords: Cholecystocolonic fistula, Cholecystocolonic fistula, Bilioenteric fistula, Pneumobilia

INTRODUCTION

Internal biliary-enteric fistulas (IBFs) are very rare, comprising 0.4%-1.9% of all biliary tract diseases[1–3]. IBFs are detected in only 0.2%-0.9% of all biliary tract operations[4–6]. Depending on the site of communication with the extrahepatic biliary tree, several types of fistulas are recognized (cholecystoduodenal, choledochoduodenal, cholecystogastric, cholecysto-choledochal, cholecystocolonic, cholecystoduodenocolic)[1,2]. Peptic ulcer and malignancies of the stomach, gallbladder, pancreas, duodenum, colon and bile ducts have been identified as etiologic factors, with cholelithiasis being the predisposing factor[2]. Iatrogenesis may be responsible for an increasing incidence of IBFs in the near future[2], as the use of endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) and the rate of cholecystectomies performed annually increase.

A cholecystocolonic (otherwise cholectystocolonic) fistula (CF) is an uncommon type of IBF, which forms a communication between the gallbladder and the hepatic flexure of the transverse colon (Figure 1)[7]. Theoretically, fistula formation was part of the natural history of acute cholecystitis prior to the era of cholecystectomy and antibiotics[8]. Its frequency among other types of IBF ranges between 8% and 13.6%[1,9,10]. CFs are associated with several severe complications, such as acute cholangitis, biliary peritonitis and biliary cirrhosis[3,11,12], leading to a global mortality rate between 10% and 15%[4,9,10].

Figure 1.

Schematic demonstration of a cholecystocolic fistula (modified from Benage et al[7]). GB: Gallbladder; CBD: Common bile duct; RHD: Right hepatic duct; PD: Pancreatic duct; CF: Cholecystocolic fistula.

Since Courvoisier first discussed spontaneous biliary fistulas in 1890[3], several authors have described interesting case-reports of CF in the literature[13–38]. However, diagnosis still remains a challenge, mainly because: (1) CF presents with varying and non-specific symptoms; (2) CF is very rare and is kept last in differential diagnosis; and (3) even advanced imaging techniques fail to demonstrate the fistulas tract in almost half of the cases[1,2,13].

In this paper, we report a case of a spontaneous CF and review the literature. The aim of this paper is to elaborate on the clinical manifestation of a CF and describe the pathophysiological mechanisms. In conclusion, we suggest that the triad of pneumobilia, chronic diarrhea and malabsorption of vitamin K could assist physicians to keep a high index of clinical suspicion for CF, leading to an early and valid diagnosis.

CASE REPORT

A 75-year-old male patient was referred to our university hospital for the investigation of chronic diarrhea and weight loss. The patient reported suffering from watery diarrhea of 3-4 bowel movements daily, lasting longer than 18 mo, and weight loss of 15 kg. The patient reported having no fever, nausea, vomiting, jaundice or abdominal pain. Medical history revealed the presence of mild diabetes mellitus type 2, which was controlled by diet, and a long-lasting smoking habit. The patient had already been subjected to colonoscopy prior to his admittance. Biopsies, including the terminal ileum, had been unrevealing. Routine laboratory tests of total white blood cell (WBC) count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), aminotransferase levels and electrolytes had also been found within normal.

On admission, the patient was afebrile. No pathological signs were found on physical examination. Laboratory investigation demonstrated alkaline phosphatase of 228 IU/L (normal range 35-120 IU/L), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase of 120 IU/L (normal: 10-45 IU/L), C-reactive protein of 6.51 mg/dL (normal: 0-0.5 mg/dL) and a prolonged prothrombin time (PT) of 20.3 s (normal: 12.2 s), that was returned to normal after parenteral administration of vitamin K (10 mg subcutaneously). Total and differential WBC counts, haemoglobulin, platelet count, ESR, aminotransferase levels, bilirubin, total protein, albumin and electrolytes ranged within normal values. Fecal examination included negative stool culture and negative examination of stool for ova and parasites. Stool examination for fat was negative, but fat determination of 24 h stool was unavailable.

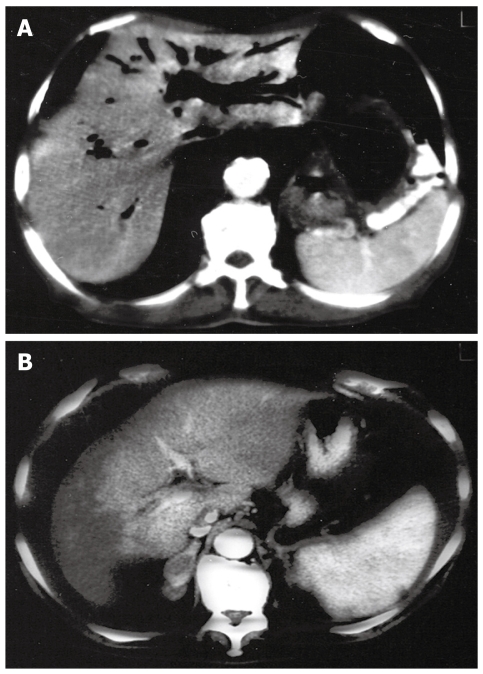

Ultrasonographic examination of the liver and the extrahepatic biliary tree demonstrated pneumobilia and moderate dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts, with a normal common bile duct and a thick-walled gallbladder (Figure 2). Enhanced CT of the abdomen confirmed massive pneumobilia and absence of common bile duct dilatation (Figure 3A). Furthermore, the presence of air was detected in the gallbladder, which was neighboured to the hepatic flexure of the colon (Figure 3B). Neither the following barium enema nor the MR cholangio-pancreatography were able to detect any fistulous tract between the gallbladder and the colon.

Figure 2.

Ultrasonographic examination revealing pneumobilia and moderate dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts, with a normal common bile duct and a thick-walled gallbladder.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography scan. A: Massive pneumobilia (“air cholangiogram”); B: Presence of air detected in the gallbladder.

The patient was subsequently referred to surgery for diagnostic laparotomy. During surgery a fistulous tract from the fundus of the gallbladder to the hepatic flexure of the colon was detected, along with an impacted large gallstone near Vater’s villa. Cholecystectomy with fistula resection and bilio-enteric anastomosis after gallstone removal was undertaken. The patient had an excellent postoperative clinical course. Diarrhea stopped, and he regained his weight within a 6 mo period.

DISCUSSION

We report a case of a spontaneous CF in a male diabetic patient, due to asymptomatic cholelithiasis. A combined triad of strong clues (pneumobilia, chronic, bile acid-induced diarrhea and malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamin K) provided high clinical suspicion for a CF, which was only confirmed during diagnostic laparotomy.

Several authors have reported their own experience of CFs[2,7,9,13–38]. Table 1 summarizes patients’ demographics, etiological factors, clinical presentation, presence of pneumobilia, means of fistula visualization and treatment option preferred. CF occurs mostly in the elderly, with a female preponderance[3,9]. In our case and in more than 90% of all cases, cholelithiasis is the main etiologic factor. Cholelithiasis may cause either recurrent episodes of acute cholecystitis/cholangitis or asymptomatic chronic calculous cholecystitis. The sequence of events that lead to the formation of the fistula include gallbladder inflammation, mechanical erosion by gallstones and gangrenous changes of both the gallbladder wall and the wall of the adjacent colon[14,17,39]. The gallstone found in the common bile duct in our patient could have affected the formation of the fistula by increasing the pressure in the biliary tree and thus enhancing the mechanical erosion of the gallbladder by another gallstone or gallstones that could easily have escaped through the fistulous tract.

Table 1.

Systematic review of cases of cholecystocolic fistulas reported in the literature

| Author (yr) | No. pts | Age (yr) | Etiology | Main clinical manifestation | Presence of pneumobilia | Means of fistula visualization | Treatment option preferred |

| Chatzoulis et al[14] (2007) | 1M | 52 | Cholelithiasis (mirizzi syndrome type IV) | Diarrhea, RUQ pain, fever | + (US, CT) | MRCP, ERCP | Cholecystectomy, fistula excision, Roux-en-Y bilio-enteric anastomosis |

| Wang et al[15] (2006) | 1F | 63 | Gallbladder and CBD stone | RUQ pain | + | ERCP | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, fistula closure |

| Singh et al[16] (2004) | 1F | 92 | Gallstones | Melena | + | - | Conservative |

| Arvanitidis et al[17] (2003) | 1M | 72 | Acute obstructive cholecystitis | Unexplained pneumobilia, history of RUQ pain | + (US) | ERCP | Open cholecystectomy, fistula resection, exploration of CBD |

| Hussien et al[18] (2003) | 1M | 63 | Xanthogra-nulomatous cholecystitis | Fever due to extraperitoneal abscesses | - | - | Cholecystectomy, fistula excision, closure of colon defect |

| Velayos Jiménez et al[9] (2003) | 1F | 79 | Cholelithiasis | Chronic diarrhea, steatorrhea (?) | + (US, CT) | BE | Conservative (antibiotics, vitamins) |

| De Keuleneer et al[19] (2002) | NR | NR | Cholelithiasis (Mirizzi syndrome type I) | Obstructive jaundice | - | ERCP | Cholecystectomy with Roux-en-Y hepato-enteric anastomosis |

| Ramos-De la Medina et al[20] (2002) | 1F | 48 | Cholelithiasis | Lower gastro-intestinal bleeding | - | - | Open surgery |

| 1F | 60 | Gallbladder malignacy | Multiple hepatic abscesses | - | - | ||

| Dutta et al[21] (2002) | 1F | 65 | NR | Diarrhea, weight loss, malabsorption (?) | + | BE, ERCP | Fistulectomy, cholecystectomy |

| Schoeters et al[22] (2002) | 1F | 81 | NR | Incidental pneumobilia, RUQ pain | + (PAF, US) | ERCP | NR |

| Fujitani et al[23] (2001) | 1F | 58 | Cholelithiasis, chronic cholecystitis | RUQ pain | - | Intraoperatively | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and fistula resection |

| Sam et al[24] (2001) | 1F | 75 | Incidental (Crohn’s disease?) | Diarrhea | - (Air in gallbladder) | BE, Tc-99m chole-scintigraphy | NR |

| Inal et al[2] (1999) | 1F | 72 | Chronic cholecystitis | Diarrhea, weight loss | + (US) | BE | Open cholecystectomy, repair of the fistula |

| Kuo et al[25] (1999) | 1F | 65 | Chronic cholecystitis | Diarrhea, fever, RUQ, jaundice | + (PAF) | BE, ERCP | Cholecystectomy, fistulas division |

| Hida et al[26] (1999) | 1F | 61 | Cholelithiasis | Incidental finding (BE screening), RUQ pain | - | BE | Laparoscopic stampling technic |

| Holst et al[27] (1999) | 1F | 76 | Gallstone disease | Diarrhea, RUQ pain | - | BE | Open cholecystectomy, fistula resection |

| Reddy et al[28] (1998) | 1F | 72 | History of acute cholecystitis | Incidental finding during laparoscopic cholecystectomy | - | - | Laparoscopic approach, tube caecostomy |

| Bornet et al[29] (1998) | NR | NR | Gallstone disease | Colonic gallstone obstruction | + (CT) | CT? | None |

| Hession et al[13] (1996) | 1F | 70 | Acute or chronic cholecystitis | Diarrhea | - | BE | NR |

| 1F | 78 | Diarrhea | - | BE | |||

| 1F | 69 | Diarrhea | - | BE | |||

| 1F | 73 | Diarrhea | - | BE | |||

| 1F | 77 | Colon ileus | + | BE | |||

| 1F | 85 | RUQ pain, diarrhea | + | BE | |||

| 1M | 43 | Melena | - | ERCP | |||

| Pérez Morera et al[30] (1996) | 2F | NR | Gallstone disease | Colonic gallstone obstruction | + | BE (postoperatively) | Repair of the fistula at a later stage |

| Ibrahim et al[31] (1995) | 1F | 68 | Cholelithiasis | Incidental finding during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, RUQ pain, diarrhea | - | Operative cholecystogramm | Laparoscopic approach |

| Gentileschi et al[32] (1995) | NR | NR | Gallstone disease | Severe diarrhea | - | BE | Laparoscopic approach |

| Prasad et al[33] (1994) | 1F | 67 | NR | Incidental finding during laparoscopic cholecystectomy | - | Operative cholangiography | Laparoscopic approach |

| Swinnen et al[34] (1994) | NR | NR | Gallstone disease | Colonic gallstone obstruction | + (US) | Colonoscopy & contrast fistulography | NR |

| Benage et al[7] (1990) | 1F | 78 | Gallstone obstruction of CBD | Malabsorption (steatorrhea, osteomalacia, hypocalcemia) | - | ERCP | Open cholecystectomy, repair of the fistula, calcium & D3 supplementation |

| Sing et al[35] (1990) | 1M | 80 | Cholelithiasis, CBD obstruction, (Billroth II?) | Diarrhea, weight loss, fat malabsorption | + (US) | ERCP | Open cholecystectomy, fistula resection, T-tube in CBD |

| Caroli-Bosc et al[36] (1990) | 2 | Gallstones | Steatorrhea | - | ERCP | Open surgery | |

| Jaundice, fever | - | ERCP, cholescintigram | ERCP sphincterotomy | ||||

| Patel et al[37] (1989) | 1F | NR | Gallstone disease | Colonic gallstone obstruction | - | ? | ? |

| Anseline et al[38] (1981) | 1F | 90 | Gallstone disease | Colonic gallstone obstruction | + (X-ray contrast) | Intraoperatively | None |

M: Male; F: Female; NR: Not reported; RUQ: Right upper quadrant; CBD: Common bile duct; PAF: Plain abdominal film; BE: Barium enema; US: Ultrasound examination; CT: Computed tomography; MRCP: MR cholangio-pancreatography; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

CF usually has a benign clinical course, remaining asymptomatic for a long time, and can only be found incidentally[24,26,28] or be suspected by the presence of unexplained pneumobilia in patients with a history of episodes of right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain[17,22]. In other cases, varying symptoms are identified like fever, nausea and vomiting, attacks of abdominal pain localized mainly in the RUQ and jaundice[15,19,23,36]. These symptoms are non-specific and cannot be directly attributable to the fistula but rather to the main etiologic factor, cholelithiasis. In these cases, clinical presentations of acute cholecystitis, cholangitis or acute/chronic pancreatitis predominate.

A more specific symptom of a CF is chronic diarrhea[2,9,13,14,21,24,27,32,35]. CFs alter the normal enterohepatic circulation of bile acids, leading to chronic watery diarrhea. This is a type 1, bile acid-induced diarrhea, which results from the stimulation of colonic mucosa by bile acids and the subsequent colonic secretion of water and electrolytes[35,40,41]. In other cases, especially when hepatic synthesis of bile acids is reduced, bypass of the distal ileum allows bile acids to escape absorption, leading to steatorrhea[7,9,35,36]. Bile salts are needed for micelle formation and subsequent absorption of fat and fat-soluble vitamins, while protein absorption is not affected. Fat malabsorption resulting from impaired micelle formation is not as severe as malabsorption resulting from pancreatic lipase deficiency, because fatty acids and monoglycerides can form lamellar structures, which to a certain extent can be absorbed[42]. Theoretically, malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, K and E) may be marked, because micelle formation is required for their absorption. However, malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins A and E has never been reported in the literature, while malabsorption of vitamin D has only been described in one female patient with CF and osteoporosis/osteomalacia[7]. The deficiency of those vitamins has to be marked to provide clinical symptoms, and laboratory evaluation is difficult and outside routine clinical practice. On the other hand, vitamin K deficiency can easily be detected by a prolonged PT and can be fixed with parenteral administration.

Rare complications of CF reported in the literature are ectopic gallstone in the colon with obstruction[29,30,34,37,38] or hemorrhage of the lower gastrointestinal tract[20], and extraperitoneal abscess with sepsis due to ascending contamination by colon bacteria[18,20,43].

Barium enema[2,9,13,21,24,26,27,32], 99mTc scintigram[24,43], CT[29,44], MRCP and ERCP[7,13–15,17,19,21,22,35,36] have all been used in order to demonstrate the fistula. However, non-visualization of the fistulous tract occurs in almost half of the cases[1,2,13,44], and, subsequently, patients are subjected to exploratory laparotomy. The presence of pneumobilia, detected by plain abdominal films, abdominal ultrasound or CT, may provide presumptive evidence for the existence of a biliary-enteric fistula, but it is non-specific[2,45]. Other radiological features include a small atrophic gallbladder adherent to neighboring organs or a shrunken thick-walled gallbladder around gallstones[2,44].

Open cholecystectomy with fistula resection and exploration of the common bile duct is the treatment of choice mostly preferred in order to avoid attacks of cholecystitis and/or cholangitis. However, successful cases using the laparoscopic approach are increasingly reported in the literature[15,23,26,28,31–33]. In non-surgical patients, either conservative treatment with antibiotics and supplementation of fat-soluble vitamins[9,16], or ERCP sphincterotomy[36,46] to reduce biliary pressure are suggested.

In conclusion, especially in patients with a history of gallstone disease, the presence of chronic watery diarrhea and vitamin K malabsorption, combined with the radiological finding of pneumobilia, form a pathognomonic triad. Either internists/gastroenterologists or surgeons should keep a high clinical index for a valid preoperative diagnosis of CFs.

Peer reviewers: Salvatore Gruttadauria, MD, Assistant Professor, Abdominal Transplant Surgery, ISMETT, Via E. Tricomi, 190127 Palermo, Italy; Chifumi Sato, Professor, Department of Analytical Health Science, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Graduate School of Health Sciences, 1-5-45 Yushima, Bunkyoku, Tokyo 113-8519, Japan

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Yamashita H, Chijiiwa K, Ogawa Y, Kuroki S, Tanaka M. The internal biliary fistula--reappraisal of incidence, type, diagnosis and management of 33 consecutive cases. HPB Surg. 1997;10:143–147. doi: 10.1155/1997/95363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inal M, Oguz M, Aksungur E, Soyupak S, Börüban S, Akgül E. Biliary-enteric fistulas: report of five cases and review of the literature. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:1145–1151. doi: 10.1007/s003300050810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LeBlanc KA, Barr LH, Rush BM. Spontaneous biliary enteric fistulas. South Med J. 1983;76:1249–1252. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198310000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atli AO, Coşkun T, Ozenç A, Hersek E. Biliary enteric fistulas. Int Surg. 1997;82:280–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angrisani L, Corcione F, Tartaglia A, Tricarico A, Rendano F, Vincenti R, Lorenzo M, Aiello A, Bardi U, Bruni D, et al. Cholecystoenteric fistula (CF) is not a contraindication for laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1038–1041. doi: 10.1007/s004640000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glenn F, Mannix H Jr. Biliary enteric fistula. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1957;105:693–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benage D, O'Connor KW. Cholecystocolonic fistula: malabsorptive consequences of lost bile acids. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;12:192–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teo M, Robets-Thomson IC. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: cholecystoenteric fistulae. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:344. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.t01-1-02759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velayos Jiménez B, Gonzalo Molina MA, Carbonero Díaz P, Díaz Gutiérrez F, Gracia Madrid A, Hernández Hernández JM. Cholecystocolic fistula demonstrated by barium enema: an uncommon cause of chronic diarrhoea. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2003;95:811–812, 809-810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stagnitti F, Mongardini M, Schillaci F, Dall'Olio D, De Pascalis M, Natalini E. [Spontaneous biliodigestive fistulae. The clinical considerations, surgical treatment and complications] G Chir. 2000;21:110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gullino D, Giordano O, Cardino L, Chiarle S. [Complication of spontaneous internal biliary fistulae (experiences in 46 cases)] Minerva Chir. 1977;32:1221–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benhamou G, Opsahl S, Le Goff JY. Can gallstones be left in the peritoneal cavity? Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1452. doi: 10.1007/s004649900883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hession PR, Rawlinson J, Hall JR, Keating JP, Guyer PB. The clinical and radiological features of cholecystocolic fistulae. Br J Radiol. 1996;69:804–809. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-69-825-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatzoulis G, Kaltsas A, Danilidis L, Dimitriou J, Pachiadakis I. Mirizzi syndrome type IV associated with cholecystocolic fistula: a very rare condition--report of a case. BMC Surg. 2007;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang WK, Yeh CN, Jan YY. Successful laparoscopic management for cholecystoenteric fistula. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:772–775. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i5.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh AK, Gervais D, Mueller P. Cholecystocolonic fistula: serial CT imaging features. Emerg Radiol. 2004;10:301–302. doi: 10.1007/s10140-004-0353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arvanitidis D, Anagnostopoulos GK, Tsiakos S, Margantinis G, Kostopoulos P. Cholecystocolic fistula demonstrated by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:526. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2003.012955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussien M, Gardiner K. Omental and extraperitoneal abscesses complicating cholecystocolic fistula. HPB (Oxford) 2003;5:194–196. doi: 10.1080/13651820310001315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Keuleneer R, Maassarani F, Lallemand B. Mirizzi syndrome with a double biliary fistula. Acta Chir Belg. 2002;102:345–347. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2002.11679331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramos-De la Medina A, Medina-Franco H. [Biliary-colonic fistulas. Analysis of 2 cases and literature review] Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2002;67:207–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutta U, Nagi B, Kumar A, Vaiphei K, Wig JD, Singh K. Pneumobilia--clue to an unusual cause of diarrhea. Trop Gastroenterol. 2002;23:138–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoeters P, Fierens H, Colemont L, Van Moer E. A cholecystocolic fistula demonstrated by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 2002;34:595. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujitani K, Hasuike Y, Tsujinaka T, Mishima H, Takeda Y, Shin E, Sawamura T, Nishisyo I, Kikkawa N. New technique of laparoscopic-assisted excision of a cholecystocolic fistula: report of a case. Surg Today. 2001;31:740–742. doi: 10.1007/s005950170083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sam JW, Ghesani N, Alavi A, Rubesin SE, Birnbaum BA. The importance of morphine-augmented cholescintigraphy for the diagnosis of a subtle cholecystocolic fistula. Clin Nucl Med. 2001;26:552–554. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200106000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo KK, Sheen PC, Chang SC, Chen JS, Lee KT, Cham CM. Spontaneous multiple cholecystoenteric fistulas--a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 1999;15:674–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hida Y, Morita T, Fujita M, Miyasaka Y, Katoh H. Laparoscopic treatment of cholecystocolonic fistula: report of a case preoperatively diagnosed by barium enema. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 1999;9:217–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holst AK, Faergemann C. [Spontaneous cholecystocolic fistula] Ugeskr Laeger. 1999;161:6790–6791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddy KM, Fiennes AG. Cholecystocolic fistula at laparoscopic cholecystectomy: primary closure and laparoscopic caecostomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8:400–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bornet G, Chiavassa H, Galy-Fourcade D, Jarlaud T, Sans N, Labbé F, Gouzy JL, Railhac JJ. [Biliary colonic ileus: an unusual cause of colonic obstruction] J Radiol. 1998;79:1499–1502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pérez Morera A, Pérez Díaz D, Calvo Serrano M, de Fuenmayor Valera ML, Martín Merino R, Turégano Fuentes F, Trinchet Hernández M, Muñoz Jiménez F. [Acute obstruction of the colon secondary to biliary lithiasis] Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1996;88:805–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibrahim IM, Wolodiger F, Saber AA, Dennery B. Treatment of cholecystocolonic fistula by laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:728–729. doi: 10.1007/BF00187951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gentileschi P, Forlini A, Rossi P, Bacaro D, Zoffoli M, Gentileschi E. Laparoscopic approach to cholecystocolic fistula: report of a case. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1995;5:413–417. doi: 10.1089/lps.1995.5.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prasad A, Foley RJ. Laparoscopic management of cholecystocolic fistula. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1789–1790. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800811226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swinnen L, Sainte T. Colonic gallstone ileus. J Belge Radiol. 1994;77:272–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sing RF, Garberman SF, Frankel AM, Chatzinoff M. Cholecystocolic fistula: an unusual presentation and diagnosis by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Surg Endosc. 1990;4:39–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00591413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caroli-Bosc FX, Ferrero JM, Grimaldi C, Dumas R, Arpurt JP, Delmont J. [Cholecystocolic fistula: from symptoms to diagnosis] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1990;14:767–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel SA, Engel JJ, Fine MS. Role of colonoscopy in gallstone ileus:--a case report. Endoscopy. 1989;21:291–292. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1012973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anseline P. Colonic gall-stone ileus. Postgrad Med J. 1981;57:62–65. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.57.663.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duzgun AP, Ozmen MM, Ozer MV, Coskun F. Internal biliary fistula due to cholelithiasis: a single-centre experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4606–4609. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i34.4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rau WS, Matern S, Gerok W, Wenz W. Spontaneous cholecystocolonic fistula: a model situation for bile acid diarrhea and fatty acid diarrhea as a consequence of a disturbed enterohepatic circulation of bile acids. Hepatogastroenterology. 1980;27:231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sackmann M, Diepolder HM. Images in hepatology: bile acid-induced diarrhea due to a choledochocolic fistula. J Hepatol. 1998;28:727. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80299-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Semrad CE, Powell DW. Chapter 143: Approach to the patient with diarrhea and malabsorption. In: L Goldman, D Ausiello., editors. Cecil Medicine. 23rd ed. Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia; 2008. pp. 1026–1027. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seto H, Watanabe N, Kageyama M, Shimizu M, Nagayoshi T, Kamisaki Y, Kakishita M. Concurrent detection of cholecystocolic fistula and hepatic abscess by hepatobiliary scintigraphy. Ann Nucl Med. 1995;9:93–95. doi: 10.1007/BF03164973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimono T, Nishimura K, Hayakawa K. CT imaging of biliary enteric fistula. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:172–176. doi: 10.1007/s002619900314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schiemann U, Dayyani V, Müller-Lisse UG, Siebeck M. [Aerobilia as an initial sign of a cholecystoduodenal fistula--a case report] MMW Fortschr Med. 2004;146:39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldberg RI, Phillips RS, Barkin JS. Spontaneous cholecystocolonic fistula treated by endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:55–56. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(88)71232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]