Abstract

Background

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force requested a decision analysis to inform their update of the recommendations for colorectal cancer screening.

Objective

To assess life-years gained and colonoscopy requirements for colorectal cancer screening strategies and identify a set of recommendable screening strategies.

Design

Decision analysis using 2 colorectal cancer microsimulation models from the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network.

Data Sources

Derived from the literature.

Target Population

U.S. average-risk 40-year-old population.

Perspective

Societal.

Time Horizon

Lifetime.

Interventions

Fecal occult blood tests (FOBTs), flexible sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy screening beginning at age 40, 50, or 60 years and stopping at age 75 or 85 years, with screening intervals of 1, 2, or 3 years for FOBT and 5, 10, or 20 years for sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy.

Outcome Measures

Number of life-years gained compared with no screening and number of screening tests required.

Results of Base-Case Analysis

Beginning screening at age 50 years was consistently better than at age 60. Decreasing the stop age from 85 to 75 years decreased life-years gained by 1% to 4%, whereas colonoscopy use decreased by 4% to 15%. Assuming equally high adherence, 4 strategies provided similar life-years gained: colonoscopy every 10 years, annual Hemoccult SENSA (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, California) testing or fecal immunochemical testing, and sensitive FOBT every 2 to 3 years with 5-yearly sigmoidoscopy. Hemoccult II and flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years alone were less effective.

Results of Sensitivity Analysis

The results were most sensitive to beginning screening at age 40 years.

Limitations

The stopping age for screening was based only on chronological age.

Conclusions

The findings support colorectal cancer screening with the following: colonoscopy every 10 years, annual screening with a sensitive FOBT, or high sensitivity FOBT every 2 to 3 years with5-yearly flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years. from ages 50 to 75 years.

Despite recent declines in both incidence and mortality (1), colorectal cancer remains the second most common cause of cancer death in the United States (2). Screening for colorectal cancer reduces mortality by allowing physicians to detect cancer at earlier, more treatable stages, as well as to identify and remove adenomatous polyps (asymptomatic benign precursor lesions that may lead to colorectal cancer). Many tests are available for screening, such as fecal occult blood tests (FOBTs), flexible sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy. Screening with FOBT (Hemoccult II, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, California) has been shown to reduce colorectal cancer mortality by 15% to 33% in randomized, controlled trials (3--5), and screening with more sensitive FOBTs, flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, or combinations of these tests may reduce the burden of colorectal cancer even more (6, 7). In the absence of adequate clinical trial data on several recommended screening strategies, microsimulation modeling can provide guidance on the risks, benefits, and testing resources required for different screening strategies to reduce the burden of colorectal cancer.

In July 2002, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concluded that there was sufficient evidence to recommend strongly that all average-risk adults 50 years of age and older should be offered colorectal cancer screening (8). However, the logistics of screening, such as the type of screening test, screening interval, and age at which to stop screening, were not evaluated in terms of the balance of benefits and potential harms. The USPSTF has again addressed recommendations for colorectal cancer screening with a systematic review of the evidence (9) on screening tests. For this assessment, the USPSTF requested a decision analysis to project expected outcomes of various strategies for colorectal cancer screening. Two independent microsimulation modeling groups from the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET), funded by the National Cancer Institute, used a comparative modeling approach to compare life-years gained relative to resource use of different strategies for colorectal cancer screening.

Methods

We used 2 microsimulation models, MISCAN (MIcrosimulation Screening Analysis) (10--12) and SimCRC (Simulation Model of Colorectal Cancer) (13), to estimate the life-years gained relative to no screening and the colonoscopies required (that is, an indicator for resource use and risk for complications) for different colorectal cancer screening strategies defined by test, age at which to begin screening, age at which to stop screening, and screening interval. We aimed to identify a set of recommendable strategies with similar clinical benefit and an efficient use of colonoscopy resources. Using 2 models (that is, a comparative modeling approach) adds credibility to the results and serves as a sensitivity analysis on the underlying structural assumptions of the models, particularly pertaining to the unobservable natural history of colorectal cancer.

Microsimulation Models

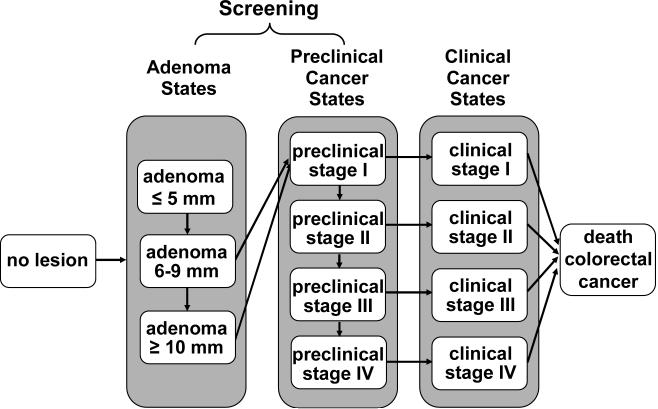

The Appendix, available at www.annals.org, describes the MISCAN and SimCRC models, and standardized model profiles are available at http://cisnet.cancer.gov/profiles/. In brief, both models simulate the life histories of a large population of individuals from birth to death. As each individual ages, there is a chance that an adenoma will develop. One or more adenomas can occur in an individual, and each adenoma can independently develop into preclinical (that is, undiagnosed) colorectal cancer (Figure 1). The risk for developing an adenoma depends on age, sex, and baseline individual risk. The models track the location and size of each adenoma; these characteristics influence disease progression and the chance of the adenoma's being found by screening. The size of adenomas can progress from small (≤5 mm) to medium (6 to 9 mm) to large (≥10 mm). Some adenomas eventually become malignant, transforming to stage I preclinical cancer. Preclinical cancer has a chance of progressing through stages I to IV, and may be diagnosed by symptoms at any stage. Survivorship after diagnosis depends on the stage of disease.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of natural history of disease as modeled by MISCAN and SimCRC models. The opportunity to intervene in the natural history through screening is noted.

The natural history component of each model was calibrated to 1975--1979 clinical incidence data (14) and adenoma prevalence from autopsy studies in the same period (15--24). We used this period because incidence rates and adenoma prevalence had not yet been affected by screening. We corrected the adenoma prevalence for studies of non-U.S. populations by using standardized colorectal cancer incidence ratios. The models use all-cause mortality estimates from the U.S. life tables and stage-specific data on colorectal cancer survival from the 1996--1999 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program (14). Table 1 compares outcomes from the natural history components of the models.

Table 1.

Comparison of the Natural History Outcomes from the MISCAN and SimCRC Models*

| Outcome | MISCAN, by Age, %* |

SimCRC, by Age, %* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 y | 50 y | 60 y | 40 y | 50 y | 60 y | |

| Adenoma prevalence | 10.9 | 28.7 | 36.7 | 10.2 | 18.3 | 29.5 |

| Size distribution of adenoMas | ||||||

| ≤5 mm | 60.9 | 64.8 | 52.6 | 59.3 | 53.9 | 51.1 |

| 6-9 mm | 20.9 | 19.0 | 25.3 | 31.6 | 34.4 | 35.8 |

| ≥10 mm | 18.2 | 16.2 | 22.1 | 9.1 | 11.7 | 13.0 |

| Location of adenomas | ||||||

| Proximal | 34.3 | 34.3 | 34.3 | 62.0 | 62.4 | 62.8 |

| Distal | 34.5 | 34.5 | 34.5 | 30.5 | 30.4 | 30.3 |

| Rectum | 34.3 | 34.3 | 34.3 | 7.5 | 7.2 | 6.8 |

| Cumulative CRC incidence | ||||||

| 10-y | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.4 |

| 20-y | 0.9 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 3.4 |

| Lifetime | 7.3 | 7.1 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 5.3 |

| Stage distribution of CRC cases | ||||||

| Stage I | 16.6 | 21.1 | 19.3 | 24.0 | 21.9 | 19.4 |

| Stage II | 23.0 | 28.3 | 31.4 | 39.6 | 35.1 | 34.8 |

| Stage III | 33.7 | 26.3 | 26.1 | 20.0 | 22.2 | 22.6 |

| Stage IV | 26.7 | 24.4 | 23.2 | 16.4 | 20.7 | 23.2 |

CRC = colorectal cancer

Because of rounding, not all percentages add to 100%

The effectiveness of a screening strategy is modeled through a test's ability to detect lesions (that is, adenomas or preclinical cancer). Once screening is introduced, a simulated person who has an underlying lesion has a chance of having it detected during a screening round depending on the sensitivity of the test for that lesion and whether the lesion is within the reach of the test. Screened persons without an underlying lesion can have a false-positive test result and undergo unnecessary follow-up colonoscopy. Hyperplastic polyps are not modeled explicitly, but their detection is reflected in the specificity of the screening tests. The models incorporate the risk for fatal complications associated with perforation during colonoscopy. Both models have been validated against the long-term reductions in incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer with annual FOBT reported in the Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study (3, 25, 26) and show good concordance with the trial results.

Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening

In consultation with the USPSTF, we included the following basic strategies: 1) no screening, 2) colonoscopy, 3) FOBT (Hemoccult II, Hemoccult SENSA [Beckman Coulter], or fecal immunochemical test), 4) flexible sigmoidoscopy (with biopsy), and 5) flexible sigmoidoscopy combined with Hemoccult SENSA. For each basic strategy, we evaluated start ages of 40, 50, and 60 years and stop ages of 75 and 85 years. For the FOBT strategies, we considered screening intervals of 1, 2, and 3 years, and for the sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy strategies we considered intervals of 5, 10, and 20 years. These variations resulted in 145 strategies: 90 single-test strategies, 54 combination-test strategies, and 1 no-screening strategy. The stop age reflects the oldest possible age at which to screen, but the actual stopping age is dictated by the start age and screening interval.

In the base case, we assumed 100% adherence for screening tests, follow-up of positive findings, and surveillance of persons found to have adenomas. Individuals with a positive FOBT result or with an adenoma detected by sigmoidoscopy were referred for follow-up colonoscopy. For years in which both tests were due for the combined strategy, the FOBT was performed first; if the result was positive, the patient was referred for follow-up colonoscopy. In those years, flexible sigmoidoscopy was done only for patients with a negative FOBT result. If findings on the follow-up colonoscopy were negative, the individual was assumed to undergo subsequent screening with colonoscopy with a 10-year interval (as long as results of the repeated colonoscopy were negative) and did not return to the initial screening schedule, as is the recommendation of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force and American Cancer Society (7, 27). All individuals with an adenoma detected were followed with colonoscopy surveillance per the Multi-Society guidelines (27, 28). The surveillance interval depended on the number and size of the adenomas detected on the last colonoscopy; it ranged from 3 to 5 years and was assumed to continue for the remainder of the person's lifetime.

We estimated the test characteristics of colorectal cancer screening from a review of the available literature (Table 2) (29). We conducted this review independently of and parallel in time with the systematic evidence review performed for the USPSTF (9).

Table 2.

Test Characteristics used in the MISCAN and SimCRC Models*

| Test Characteristic | Base-Case Value, % | Sensitivity Analysis, % |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Best-Case Value | Worst-Case Value | ||

| Hemoccult II | |||

| Specificity | 98.0 | 99.0 | 95.0 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas ≤ 5 mm† | 2.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas 6-9 mm | 5.0 | 13.7 | 5.0 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas ≥ 10 mm | 12.0 | 27.5 | 8.9 |

| Sensitivity for cancer | 40.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 |

| Reach | Whole colorectum | Not varied | Not varied |

| Mortality rate | 0 | Not varied | Not varied |

| Hemoccult SENSA | 92.5 | 95.0 | 90.0 |

| Specificity | 7.5 | 5.0 | 10.0 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas ≤ 5 mm† | 12.4 | 26.2 | 10.0 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas 6-9 mm | 23.9 | 49.4 | 17.7 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas ≥ 10 mm | 70.0 | 87.0 | 50.0 |

| Sensitivity for cancer | Whole colorectum | Not varied | Not varied |

| Reach | 0 | Not varied | Not varied |

| Mortality rate | 92.5 | 95.0 | 90.0 |

| Fecal immunochemical test | |||

| Specificity | 95.0 | 98.0 | 92.5 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas ≤ 5 mm† | 5.0 | 2.0 | 7.5 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas 6-9 mm | 10.1 | 24.0 | 7.5 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas ≥ 10 mm | 22.0 | 48.0 | 16.0 |

| Sensitivity for cancer | 70.0 | 87.0 | 50.0 |

| Reach | Whole colorectum | Not varied | Not varied |

| Mortality rate | 0 | Not varied | Not varied |

| Sigmoidoscopy (within reach) | |||

| Specificity | 92.0 | Not varied | Not varied |

| Sensitivity for adenomas ≤ 5 mm | 75.0 | 79.0 | 70.0 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas 6-9 mm | 85.0 | 92.0 | 80.0 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas ≥ 10 mm | 95.0 | 99.0 | 92.0 |

| Sensitivity for cancer‡ | 95.0 | 99.0 | 92.0 |

| Reach | 80 (to sigmoid-descending junction), | 100 (to sigmoid-descending junction), | 60 (to sigmoid-descending junction), |

| Mortality rate | 0 | Not varied | Not varied |

| Colonoscopy (within reach) | |||

| Specificity | 90.0 | Not varied | Not varied |

| Sensitivity for adenomas ≤ 5 mm | 75.0 | 79.0 | 70.0 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas 6-9 mm | 85.0 | 92.0 | 80.0 |

| Sensitivity for adenomas ≥ 10 mm | 95.0 | 99.0 | 92.0 |

| Sensitivity for cancer | 95.0 | 99.0 | 92.0 |

| Reach | 95 (to end of cecum), remaining 5 between | Not varied | Not varied |

| Mortality rate | 1 per 10 000 | Not varied | Not varied |

Data obtained from reference 29.

We assume that small adenomas do not bleed and cannot be detected by fecal occult blood tests (FOBTs). The sensitivity of FOBTs for adenomas ≤ 5 mm is based on the false-positive rate (that is, 1 - specificity).

The sensitivity of sigmoidoscopy for colorectal cancer over the whole colorectum is 72% with MISCAN and 61% with SimCRC

Evaluation of Outcomes

Determination of Efficient Strategies

The most effective strategy was defined as the one with the greatest life-years gained relative to no screening. However, it is important to consider the relative intensity of test use required to achieve those gains. The more effective strategies tended to be associated with more colonoscopies on average in a person's lifetime, which translated into an increased risk for colonoscopy-related complications. We used an approach that mirrors that of cost-effectiveness analysis (30) to identify the set of efficient, or dominant, strategies within each test category. A strategy was considered dominant when no other strategy or combination of strategies provided more life-years with the same number of colonoscopies. We conducted this analysis separately for each of the 5 basic screening strategies because the number of noncolonoscopy tests differed by strategy. We then ranked the efficient screening strategies by increasing effectiveness and calculated the incremental number of colonoscopies (ΔCOL) per 1000, the incremental life-years gained (ΔLYG) per 1000, and the incremental number of colonoscopies necessary to achieve a year of life (ΔCOL/ΔLYG) relative to the next less effective strategy, which we call the “efficiency ratio.” The line connecting the set of efficient strategies is called the (efficient) frontier. We also identified “near-efficient” strategies—strategies that yielded life-years gained within 98% of the efficient frontier.

Determination of Recommendable Strategies at a Certain Level of Effectiveness

We further considered only efficient or near-efficient strategies. We assumed that the set of recommendable strategies would have the same start and stop age because recommending different start and stop ages by test may be confusing for patients and practitioners. We looked at the incremental number of colonoscopies relative to the life-years gained to determine what would be reasonable start and stop ages. For a given start and stop age we selected a colonoscopy strategy; the default was the generally recommended 10-year screening interval. From the other test categories we selected strategies with a screening effectiveness most similar to that of colonoscopy, and with a lower efficiency ratio than that for colonoscopy. This was because strategies with more intensive use of tests other than colonoscopy should have a lower efficiency ratio than strategies with less intensive (or no) use of noncolonoscopy tests (that is, this ratio would be higher if other tests were included in the numerator). Alternative sets of recommendable strategies for colorectal cancer screening were obtained with different colonoscopy strategies selected as the initial comparator.

Sensitivity Analyses

The primary sensitivity analysis was the comparison of findings across the 2 independently developed microsimulation models. We also performed sensitivity analyses on test characteristics in which we used all of the least favorable values in a worst-case analysis and all of the most favorable values in a best-case analysis (Table 2). For colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy, we used the confidence intervals reported in the meta-analysis by van Rijn (31) as the range tested. For FOBT, we used the ranges reported in the literature (9, 29). To assess the relative effect of decreased adherence, we explored the impact of overall adherence rates of 50% and 80%. We incorporated correlation of screening behavior within an individual by assuming that the population comprises 4 groups: those who are never screened and those with low, moderate, and high adherence; 10% of the population was in the never-screened group and 30% were in each of the other groups. For both overall screening adherence assumptions (that is, 50% and 80%), we assumed that adherence with follow-up and surveillance was 75%, 85%, and 95% for those with low, moderate, and high adherence, respectively. We assumed that individuals remain in their screening behavior group.

Role of the Funding Source

The National Cancer Institute supported the infrastructure for the CISNET models. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded this work and provided project oversight and review. The authors worked with 4 USPSTF members to specify the overall questions, select the strategies, and resolve methodologic issues during the conduct of the review. The draft decision analysis was reviewed by 3 external peer reviewers (listed in the acknowledgments) and was revised for the final version. The authors have sole responsibility for the models and model results.

Institutional Review Board

This research did not include patient-specific information and was exempt from institutional review board review.

Results

Table 3 presents the life-years gained, the number of colonoscopies, and the efficiency ratio for each efficient and near-efficient colonoscopy strategy for both models. Similar results for the other tests can be found in the Appendix Table, available at www.annals.org. For illustration, Figure 2 presents the life-years gained relative to the number of colonoscopies and the efficient frontier for all colonoscopy strategies.

Table 3.

Efficient and Near-Efficient Strategies for Colonoscopy Screening*

| Strategy Test, Age Begin-Age Stop, Interval† | Outcomes per 1000 Persons |

ΔCOL/ΔLYG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL | LYG | ΔCOL | ΔLYG | ||

| MISCAN | |||||

| COL, 60-75, 20 | 2175 | 156 | - | - | - |

| COL, 50-75, 20 | 3325 | 203 | 1150 | 47 | 24.7 |

| COL, 50-75, 10 | 4136 | 230 | 811 | 27 | 29.6 |

| COL, 50-85, 10 | 4534 | 236 | 398 | 5 | 72.9 |

| COL, 50-75, 5 | 5895 | 254 | 1362 | 18 | 74.8 |

| COL, 50-85, 5 | 6460 | 257 | 565 | 4 | 156.1 |

| SimCRC | |||||

| COL, 60-75, 20 | 1780 | 165 | - | - | - |

| COL, 50-75, 20 | 2885 | 246 | 1106 | 82 | 13.5 |

| 3756 | 271 | 871 | 25 | 34.7 | |

| COL, 50-85, 10 | 4114 | 273 | 358 | 2 | Near-efficient‡ |

| COL, 50-75, 5 | 5572 | 281.6 | 1816 | 10 | 178.8 |

| COL, 50-85, 5 | 6031 | 282.1 | 459 | 0.5 | 975.7 |

COL = colonoscopy; LYG = life-years gained compared with no screening; ΔCOL = incremental number of colonoscopies compared with the next-best nondominated strategy; ΔLYG = incremental number of life-years gained compared with the next-best nondominated strategy. Bold indicates recommendable strategy.

Age and intervals expressed as years.

Strategy yields life-years gained within 98% of the efficient frontier.

Appendix Table.

Efficient and Near-Efficient Strategies*

| Strategy Test, Age Begin-Age Stop, Interval† | Outcomes per 1000 Persons |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL | Non-COL Tests | LYG | ΔCOL | ΔLYG | ΔCOL/ΔLYG‡ | |

| Colonoscopy screening | ||||||

| MISCAN | ||||||

| 1 COL, 60-75, 20 | 2175 | 0 | 156 | - | - | - |

| 2 COL, 50-75, 20 | 3325 | 0 | 203 | 1150 | 47 | 24.7 |

| 3 COL, 50-75,10 | 4136 | 0 | 230 | 811 | 27 | 29.6 |

| 4 COL, 50-85, 10 | 4534 | 0 | 236 | 398 | 5 | 72.9 |

| 5 COL, 50-75, 5 | 5895 | 0 | 254 | 1362 | 18 | 74.8 |

| 6 COL, 50-85, 5 | 6460 | 0 | 257 | 565 | 4 | 156.1 |

| SimCRC | ||||||

| 1 COL, 60-75, 20 | 1780 | 0 | 165 | - | - | - |

| 2 COL, 50-75, 20 | 2885 | 0 | 246 | 1106 | 82 | 13.5 |

| 3 COL, 50-75, 10 | 3756 | 0 | 271 | 871 | 25 | 34.7 |

| 4 COL, 50-85, 10 | 4114 | 0 | 273 | Near-efficient | ||

| 5 COL, 50-75, 5 | 5572 | 0 | 281.6 | 1,816 | 10 | 178.8 |

| 6 COL, 50-85, 5 | 6031 | 0 | 282.1 | 459 | 0.5 | 975.7 |

| Hemoccult II | ||||||

| MISCAN | ||||||

| 1 Hemoccult II, 60-75, 3 | 681 | 4435 | 89 | - | - | - |

| 2 Hemoccult II, 60-75, 2 | 854 | 5784 | 105 | 172 | 16 | 10.6 |

| 3 Hemoccult II, 50-75, 3 | 1033 | 6834 | 121 | Near-efficient | ||

| 4 Hemoccult II, 50-75, 2 | 1335 | 9510 | 149 | 482 | 44 | 11.0 |

| 5 Hemoccult II, 50-85, 2 | 1513 | 11 162 | 158 | Near-efficient | ||

| 6 Hemoccult II, 50-75, 1 | 1982 | 16 232 | 194 | 647 | 45 | 14.3 |

| 7 Hemoccult II, 50-85, 1 | 2186 | 18 409 | 202 | 203 | 8 | 25.5 |

| SimCRC | ||||||

| 1 Hemoccult II, 60-75, 3 | 425 | 4291 | 75 | - | - | - |

| 2 Hemoccult II, 50-75, 3 | 699 | 6941 | 129 | 275 | 54 | 5.1 |

| 3 Hemoccult II, 50-75, 2 | 921 | 9422 | 162 | 221 | 33 | 6.7 |

| 4 Hemoccult II, 50-75, 1 | 1456 | 16 239 | 218 | 536 | 56 | 9.6 |

| 5 Hemoccult II, 50-85, 1 | 1712 | 18 262 | 223 | 256 | 5 | 47.9 |

| Hemoccult SENSA | ||||||

| MISCAN | ||||||

| 1 Hemoccult SENSA, 60-75, 3 | 1363 | 3824 | 134 | - | - | - |

| 2 Hemoccult SENSA, 60-75, 2 | 1647 | 4732 | 149 | Near-efficient | ||

| 3 Hemoccult SENSA, 50-75, 3 | 2121 | 5596 | 181 | 758 | 47 | 16.0 |

| 4 Hemoccult SENSA, 50-75, 2 | 2584 | 7014 | 205 | 463 | 24 | 19.5 |

| 5 Hemoccult SENSA, 50-85, 2 | 2801 | 7679 | 211 | Near-efficient | ||

| 6 Hemoccult SENSA, 50-75, 1 | 3350 | 9541 | 230 | 766 | 25 | 30.9 |

| 7 Hemoccult SENSA, 50-85, 1 | 3538 | 9904 | 232 | 188 | 2 | 80.6 |

| SimCRC | ||||||

| 1 Hemoccult SENSA, 60-75, 3 | 934 | 3735 | 123 | - | - | - |

| 2 Hemoccult SENSA, 50-75, 3 | 1587 | 5554 | 201 | 653 | 78 | 8.4 |

| 3 Hemoccult SENSA, 50-75, 2 | 1957 | 7006 | 228 | 370 | 28 | 13.3 |

| 4 Hemoccult SENSA, 50-75,1 | 2654 | 9573 | 259 | 698 | 31 | 22.9 |

| 5 Hemoccult SENSA, 50-85, 1 | 2996 | 9918 | 262 | 341 | 3 | 128.2 |

| Fecal immunochemical test | ||||||

| MISCAN | ||||||

| 1 FIT, 60-75, 3 | 1158 | 4037 | 129 | - | - | - |

| 2 FIT, 60-75, 2 | 1403 | 5098 | 144 | Near-efficient | ||

| 3 FIT, 50-75, 3 | 1769 | 6089 | 173 | 611 | 44 | 14.0 |

| 4 FIT, 50-75, 2 | 2184 | 7916 | 198 | 415 | 25 | 16.5 |

| 5 FIT, 50-85, 2 | 2396 | 8895 | 206 | Near-efficient | ||

| 6 FIT, 50-75, 1 | 2949 | 11 773 | 227 | 765 | 30 | 25.9 |

| 7 FIT, 50-85, 1 | 3155 | 12 582 | 231 | 206 | 4 | 49.1 |

| SimCRC | ||||||

| 1 FIT, 60-75, 3 | 772 | 3943 | 118 | - | - | - |

| 2 FIT, 50-75, 3 | 1286 | 6047 | 193 | 514 | 75 | 6.9 |

| 3 FIT, 50-75, 2 | 1614 | 7908 | 222 | 327 | 29 | 11.3 |

| 4 FIT, 50-75, 1 | 2295 | 11 830 | 256 | 681 | 35 | 19.7 |

| 5 FIT, 50-85, 1 | 2623 | 12 587 | 260 | 328 | 3 | 95.7 |

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy | ||||||

| MISCAN | ||||||

| 1 FSIG, 60-75, 20 | 1047 | 917 | 114 | - | - | - |

| 2 FSIG, 60-75, 10 | 1311 | 1531 | 140 | Near-efficient | ||

| 3 FSIG, 60-75, 5 | 1491 | 2617 | 159 | Near-efficient | ||

| 4 FSIG, 50-75, 10 | 1685 | 2339 | 177 | Near-efficient | ||

| 5 FSIG, 50-75, 5 | 1911 | 4139 | 203 | 864 | 89 | 9.7 |

| 6 FSIG, 50-85, 5 | 1996 | 4745 | 207 | 85 | 4 | 22.3 |

| SimCRC | ||||||

| 1 FSIG, 60-75, 20 | 438 | 889 | 94 | - | - | - |

| 2 FSIG, 50-75, 20 | 662 | 1662 | 147 | 224 | 53 | 4.2 |

| 3 FSIG, 50-85, 20 | 674 | 1661 | 147 | Near-efficient | ||

| 4 FSIG, 50-75, 10 | 808 | 2455 | 176 | 146 | 29 | 5.0 |

| 5 FSIG, 50-75, 5 | 995 | 4483 | 199 | 187 | 22 | 8.4 |

| 6 FSIG, 50-85, 5 | 1064 | 5088 | 201 | 68 | 2 | 38.5 |

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy plus Hemoccult SENSA | ||||||

| MISCAN | ||||||

| 1 FSIG + SENSA, 60-75, 20, 3 | 1817 | 4142 | 163 | - | - | - |

| 2 FSIG + SENSA, 60-75, 10, 3 | 1933 | 4497 | 171 | Near-efficient | ||

| 3 FSIG + SENSA, 60-75, 5, 3 | 2031 | 5220 | 179 | 213 | 15 | 14.0 |

| 4 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 20, 3 | 2658 | 6192 | 213 | Near-efficient | ||

| 5 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 10, 3 | 2756 | 6573 | 221 | Near-efficient | ||

| 6 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 5, 3 | 2870 | 7685 | 230 | 839 | 52 | 16.3 |

| 7 FSIG + SENSA, 50-85, 5, 3 | 3042 | 8380 | 233 | 172 | 3 | 60.7 |

| 8 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 5, 2 | 3142 | 8588 | 235 | 100 | 2 | 62.3 |

| 9 FSIG + SENSA, 50-85, 10, 2 | 3245 | 8350 | 232 | Near-efficient | ||

| 10 FSIG + SENSA, 50-85, 5, 2 | 3321 | 9267 | 237 | 179 | 2 | 74.3 |

| 11 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 20, 1 | 3558 | 9590 | 236 | Near-efficient | ||

| 12 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 10, 1 | 3591 | 9738 | 237 | Near-efficient | ||

| 13 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 5, 1 | 3635 | 10 279 | 239 | 314 | 2 | 139.8 |

| 14 FSIG + SENSA, 50-85, 20, 1 | 3734 | 9915 | 238 | Near-efficient | ||

| 15 FSIG + SENSA, 50-85, 10, 1 | 3768 | 10 081 | 239 | Near-efficient | ||

| 16 FSIG + SENSA, 50-85, 5, 1 | 3808 | 10 611 | 240 | 172 | 1 | 154.5 |

| SimCRC | ||||||

| 1 FSIG + SENSA, 60-75, 20, 3 | 956 | 7763 | 152 | - | - | - |

| 2 FSIG + SENSA, 60-75, 10, 3 | 999 | 11 104 | 161 | 44 | 9 | 4.7 |

| 3 FSIG + SENSA, 60-75, 5, 3 | 1045 | 10 064 | 169 | 45 | 8 | 5.5 |

| 4 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 10, 3 | 1621 | 12 485 | 246 | Near-efficient | ||

| 5 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 5, 3 | 1655 | 11 623 | 257 | 611 | 88 | 7.0 |

| 6 FSIG + SENSA, 50-85, 5, 3 | 1908 | 9484 | 260 | Near-efficient | ||

| 7 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 5, 2 | 1994 | 12 265 | 265 | 338 | 8 | 41.7 |

| 8 FSIG + SENSA, 50-85, 5, 2 | 2298 | 9895 | 268 | Near-efficient | ||

| 9 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 20, 1 | 2647 | 10 214 | 270 | Near-efficient | ||

| 10 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 10, 1 | 2653 | 14 403 | 271 | Near-efficient | ||

| 11 FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 5, 1 | 2666 | 13 593 | 274 | 673 | 9 | 75.7 |

| 12 FSIG + SENSA, 50-85, 20, 1 | 2981 | 7133 | 272 | Near-efficient | ||

| 13 FSIG + SENSA, 50-85, 10, 1 | 2987 | 5794 | 274 | Near-efficient | ||

| 14 FSIG + SENSA, 50-85, 5, 1 | 2996 | 10 875 | 276 | 330 | 2 | 154.4 |

COL = colonoscopy; FSIG = flexible sigmoidoscopy; LYG = life-years gained compared with no screening; SENSA = Hemoccult SENSA; ΔCOL = incremental number of colonoscopies compared with the next-best nondominated strategy; ΔLYG = incremental number of life-years gained compared with the next-best nondominated strategy. Bold indicates recommendable strategy

Age and intervals expressed as years.

Near-efficient strategies yield life-years gained within 98% of the efficient frontier.

Additional appendix tables and figures are available at www.ahrq.gov

Figure 2.

Colonoscopies and life-years gained (compared with no screening) for a cohort of 1,000 40-year-olds for 18 colonoscopy screening strategies that vary by start age, stop age and screening interval. The solid line represents the frontier of efficient strategies.

Age at Which To Begin Screening

The results from the MISCAN and SimCRC models were consistent in evaluating strategies with age to begin screening of 50 or 60 years, with the start age of 50 predominating among the efficient or near-efficient strategies (Table 3, Appendix). However, the SimCRC model showed favorable results for the strategies in which screening begins at age 40, but these results were not corroborated by the MISCAN model. To illustrate this difference, Figure 2 shows the efficient frontier with age 40 included for colonoscopy (“Frontier 40, 50, 60y”) and without age 40 (“Frontier 50, 60y”). Similar results were found for the other tests (results not shown). Because the evidence for both adenoma prevalence at age 40 and the duration of the adenoma--carcinoma sequence is weak, we restricted further analysis to start ages of 50 and 60.

Age at Which To Stop Screening

For both models and all tests, decreasing the stopping age from 85 to 75 yielded small reductions in life-years gained relative to large reductions in the number of colonoscopies required (Appendix Table). For example, stopping screening at age 75 instead of 85 for colonoscopy every 10 years would decrease the number of life-years gained with colonoscopy screening by 5 per 1000 individuals for MISCAN and by 2 per 1000 individuals for SimCRC, but would substantially decrease the number of colonoscopies by 398 and 358 per 1000 individuals for MISCAN and SimCRC, respectively (Table 3). This is illustrated by the substantial reduction in the efficiency ratio for these 2 strategies, from 73 to 30 for MISCAN and 179 to 35 for SimCRC.

Screening Interval

In general, strategies with longer intervals provided fewer life-years gained than did strategies with shorter intervals. For all single test strategies, the currently recommended intervals of annual FOBT, flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years, and colonoscopy every 10 years provided a reasonable ratio of incremental colonoscopies per life-year gained (10--35) for ages 50 to 75 (Appendix Table). The results from both models showed that the current recommendation for the combination of flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years with a high-sensitivity FOBT annually had a high efficiency ratio, and that moving to a strategy of sigmoidoscopy every 5 years with FOBT every 3 years would minimally decrease the number of life-years gained with combination screening (by 9 per 1000 individuals for MISCAN and by 17 per 1000 individuals for SimCRC) and would substantially decrease the number of colonoscopies (by 765 per 1000 individuals for MISCAN and by 1011 per 1000 individuals for SimCRC for ages 50 to 75) (Appendix Table). This would substantially reduce the incremental colonoscopies required for an additional life-year gained from 155 to 16 for MISCAN and from 154 to 7 for SimCRC.

Identifying a Set of Recommendable Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening

In the preceding analysis, we found that a start age of 50 and a stop age of 75 were most reasonable when we considered both benefit and resource use. For those start and stop ages, we first selected the colonoscopy strategy with 10-year intervals because this has been the recommended interval; shortening the interval resulted in a marked increase in efficiency ratio (from 75 to 30 for MISCAN and 179 to 35 for SimCRC) (Table 3). The noncolonoscopy strategies were then chosen to have the same start and stop ages and a lower efficiency ratio, while saving similar life-years as that for colonoscopy (Table 4). The sensitive annual FOBT strategies (Hemoccult SENSA and fecal immunochemical test) were similar to colonoscopy every 10 years in terms of life-years gained. The less sensitive FOBT (Hemoccult II) performed annually did not have effectiveness similar to that of the other FOBTs or to that of colonoscopy. Flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years, although showing a reasonable efficiency ratio, did not have effectiveness similar to that of the other strategies. The combination of flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years with Hemoccult SENSA every 3 years had a reasonable efficiency ratio (lower than that of colonoscopy and the sensitive FOBTs) and had relatively similar life-years gained. Had we selected the 20-year interval for colonoscopy as the comparator strategy instead of the 10-year interval, the set of strategies would include biennial screening for sensitive FOBT, annual screening for Hemoccult II, and screening with sigmoidoscopy every 10 years in combination with FOBT every 3 years. The life-years gained for this set of screening strategies is approximately 8% to 12% lower than that shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Outcomes for the Recommendable Set of Efficient Screening Strategies*

| Strategy Test, Age Begin-Age Stop, Interval | Outcomes per 1000 Persons |

Efficiency Ratio† | Incidence Reduction, % | Mortality Reduction, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL | Non-COL Tests | LYG | ||||

| MISCAN | ||||||

| COL, 50-75, 10 | 4136 | 0 | 230 | 29.6 | 51.9 | 64.6 |

| Hemoccult SENSA, 50-75, 1 | 3350 | 9541 | 230 | 30.9 | 49.7 | 66.0 |

| FIT, 50-75, 1 | 2949 | 11 773 | 227 | 25.9 | 47.2 | 64.6 |

| Hemoccult II, 50-75, 1 | 1982 | 16 232 | 194 | 14.3 | 37.1 | 55.3 |

| FSIG, 50-75, 5 | 1911 | 4139 | 203 | 9.7 | 46.8 | 58.5 |

| FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 5, 3 | 2870 | 7685 | 230 | 16.3 | 51.2 | 65.7 |

| SimCRC | ||||||

| COL, 50-75, 10 | 3756 | 0 | 271 | 34.7 | 80.6 | 84.4 |

| Hemoccult SENSA, 50-75, 1 | 2654 | 9573 | 259 | 22.9 | 73.2 | 81.2 |

| FIT, 50-75, 1 | 2295 | 11 830 | 256 | 19.7 | 70.8 | 80.0 |

| Hemoccult II, 50-75,1 | 1456 | 16 239 | 218 | 9.6 | 56.6 | 69.0 |

| FSIG, 50-75, 5 | 995 | 4483 | 199 | 8.4 | 59.0 | 62.2 |

| FSIG + SENSA, 50-75, 5, 3 | 1655 | 11 623 | 257 | 7.0 | 72.2 | 79.3 |

COL = colonoscopy; FIT = fecal immunochemical test; FSIG = flexible sigmoidoscopy; LYG = life-years gained compared with no screening.

Efficiency ratio corresponds with ΔCOL/ΔLYG in the Appendix Table and represents the relative burden per unit of benefit achieved.

Sensitivity Analysis

Our overall conclusions did not change with variations in test characteristics. As expected, results for the worst-case analysis showed fewer life-years gained than results for the base case, and the best-case analysis had more life-years gained. For strategies that remained on the efficient frontier, the incremental number of colonoscopies per life-year gained was typically greater than the base-case value with the best-case assumption, and lower with the worst-case assumption.

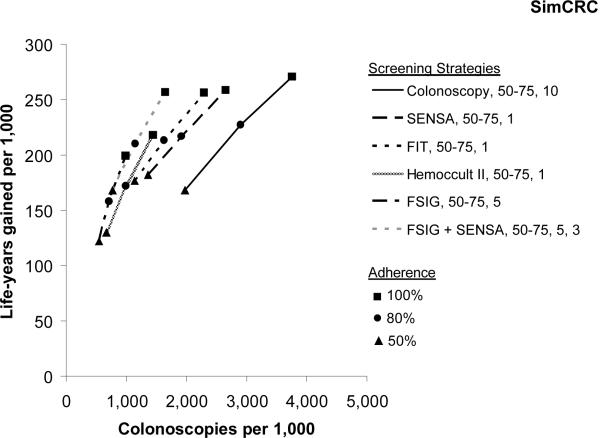

Figure 3 shows the expected number of colonoscopies and life-years gained for adherence of 50%, 80%, and 100% for the recommended strategies shown in Table 4. When adherence was relatively high at 80%, the colonoscopy strategy (that is, screening every 10 years from ages 50 to 75) was the most effective in term of life-years gained; Hemoccult SENSA, fecal immunochemical test, and the combination strategies all provided life-years gained within 8% of those of the colonoscopy strategy. When overall adherence was only 50%, the colonoscopy strategy was no longer the most effective, and Hemoccult SENSA, fecal immunochemical test, and the combination strategies had life-years gained greater or equivalent to those of the colonoscopy strategy. Annual Hemoccult II and flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years remained the least attractive alternatives in terms of life-years gained across different adherence levels.

Figure 3.

Colonoscopies and life-years gained by adherence level for the recommendable set of screening strategies. SENSA = Hemoccult SENSA; FIT = fecal immunochemical test; FSIG = flexible sigmoidoscopy

Discussion

We used 2 independent microsimulation models to evaluate different strategies for colorectal cancer screening defined by screening test, age at which to begin screening, interval to repeat screening, and age at which to stop screening. Our goal was to provide the USPSTF with information that synthesizes and translates multiple sources of data, such as screening test characteristics, into projections of clinical benefit and resource utilization for multiple screening options. We found several screening strategies (colonoscopy every 10 years, high-sensitivity FOBT performed annually, and flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years with Hemoccult SENSA every 2 to 3 years) that provide similar gains in life-years—if there is equally high adherence for all aspects of the screening process. Our analysis also found that annual FOBT with a lower-sensitivity test (for example, Hemoccult II) and flexible sigmoidoscopy alone resulted in fewer life-years gained relative to other strategies. Our analysis confirmed the current recommendation to begin screening at age 50 in an asymptomatic general population and showed that stopping at age 75 after consecutive negative screenings since age 50 provides almost the same benefit as stopping at age 85, but with substantially fewer colonoscopy resources and risk for complications.

Our decision analysis represents the first time that the USPSTF has included simulation modeling to help inform their decision on recommendations. The USPSTF had previously recommended screening for all asymptomatic persons beginning at age 50 but did not recommend one test over another or an age at which to stop screening (6). Although randomized, controlled trials are the preferred method for establishing effectiveness of (screening) interventions, they are expensive, require long follow-up, and can address only a limited number of comparison groups. However, well-validated microsimulation models may be used to highlight the tradeoff between clinical benefit and resource utilization from different screening policies and inform decision making with standardized comparisons of net benefits and risks. The process with which our analysis was conducted represents an important advancement from evidence-based to evidence-informed medicine, and the use of more than one model, as advocated by CISNET, adds credibility when model results agree.

We found that colorectal cancer screening with high-sensitivity FOBT (Hemoccult SENSA or fecal immunochemical test) provided similar life-years gained as colonoscopy, even though the individual test characteristics were substantially better for colonoscopy (Table 2). This finding was partially due to the fact the FOBT must be performed every year compared with every 10 years for colonoscopy, and the test characteristics are assumed to remain unchanged with each subsequent screening. For example, if an adenoma was missed by a screening test in one cycle, then the chance that it would be missed again on the next examination is still based on the false-negative rate (1 - sensitivity for adenomas). There is little evidence on whether test sensitivity varies with increasing rounds of testing. In addition, a substantial percentage of individuals on annual FOBT screening will eventually have a false-positive screening test with referral for colonoscopy. Once confirmed to be negative by colonoscopy they are then place on colonoscopy screening every 10 years, as per guidelines. For example, with a specificity of 92.5% for Hemoccult SENSA, the percentage of people in a colonoscopy screening program is about 54% after 10 FOBTs and about 79% after 20 FOBTs.

There has been no recommended stopping age for colorectal cancer screening (7, 27). However, our results indicate that continued screening in 75-year-old persons after consecutive negative screenings since age 50 will add little benefit. Individuals with continuous negative findings by age 75 are unlikely to have a missed adenoma at their last screening or to develop an adenoma that progresses to cancer and subsequent cancer death after their last screening. Surveillance colonoscopies for patients with adenomas detected are continued without a stopping age. We note that our analysis used chronologic age rather than comorbidity-adjusted life expectancy and that the decision to stop screening in practice should consider the age and health of the patient. As a guide, life expectancy at age 75 is 10.5 for men and 12.5 years for women, respectively (32).

A few findings can be explained by model differences. Both models incorporate assumptions about the adenoma--carcinoma sequence (that is, the development of colorectal cancer from adenomas), for which limited data are available to estimate the time that it takes (on average) for an adenoma to develop into preclinical cancer. For example, in the MISCAN model, the average time from adenoma development to colorectal cancer diagnosis is 10 years among individuals with colorectal cancer diagnosed (that is, dwell time), whereas in the SimCRC model this value is about 22 years. The implications of these differences were more life-years gained with screening in general, and more favorable results for beginning screening at age 40, with the SimCRC model. The former implication had minimal effect on our conclusions because the relative findings were consistent across models. The latter implication resulted in eliminating the start age of 40 from consideration. Another difference between the models is the distribution of adenomas in the colorectal tract (see the Appendix and Table 1). In the MISCAN model, adenomas are assumed to have the same distribution as colorectal cancers, while the SimCRC model is calibrated to the distribution of adenomas from autopsy studies. As a result, the MISCAN model found strategies involving sigmoidoscopy to be more effective than did the SimCRC model because a larger proportion of adenomas are within the reach of the sigmoidoscope. Despite this difference, both model results found that the strategy of sigmoidoscopy every 5 years was not as effective as annual screening with a sensitive FOBT or with colonoscopy every 10 years.

There are several limitations and caveats to consider. First, we evaluated only colorectal cancer strategies requested by the USPSTF on the basis of their review of the evidence in 2002 (8), and we did not include newer screening tests, such as computed tomographic colonography or the DNA stool test (9, 27). Second, because we were not asked to provide a cost-effectiveness analysis, we used the number of colonoscopies as a proxy for resource utilization, as well as nonfatal adverse effects from screening. However, this does not capture all resources required per scenario, although we report the numbers of non-colonoscopy tests (that is, FOBT or flexible sigmoidoscopy) required for each strategy. Third, we assumed 100% adherence with screening, follow-up (that is, chance of undergoing diagnostic colonoscopy if a screening test result is positive), and surveillance for all scenarios to provide outcomes associated with the strategies as they were specified. In practice, adherence is much lower than 100% and varies across type of screening test. We conducted a sensitivity analysis that varied overall adherence but not differentially across strategies. We chose to evaluate strategies assuming equivalent adherence because it is uncertain whether adherence will be higher with noninvasive but more frequent testing, or invasive but less frequent testing. Because we considered 3 different adherence scenarios in Figure 3, readers can compare different adherence levels themselves. We emphasize that in practice adherence is critical and that ultimately the best option for a patient is the one that he or she will attend (7, 27). In addition, issues pertaining to the implementation of a screening program, including endoscopy capacity (33--35), professional qualification (36, 37), insurance coverage, shared decision making, and how to increase adherence with colorectal cancer screening (38), are important considerations for implementing recommendations in practice.

In conclusion, our results support colorectal cancer screening with colonoscopy every 10 years, a sensitive FOBT annually, or high sensitive FOBT every 2 to 3 years with a -yearly flexible sigmoidoscopy from ages 50 to 75 years. Our findings in general support the 2002 USPSTF recommendations for colorectal cancer screening, with a few exceptions. First, while there is currently no recommended stopping age for colorectal cancer screening, we found that continuing screening after age 75 in individuals who have had regular, consistently negative screenings since age 50 provides minimal benefit for the resources required. Second, we found that screening with Hemoccult II annually and flexible sigmoidoscopy alone every 5 years does not provide effectiveness similar to that of screening annually with a sensitive FOBT or every 10 years with colonoscopy. Finally, if a sensitive FOBT is used, the FOBT screening interval can be extended to 3 years when used in combination with flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years. These conclusions were corroborated by 2 independent microsimulation models.

From Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York; Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; and University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following for helpful comments and review of earlier versions of this paper: Mary Barton, MD, MPH, and William Lawrence, MD, MSc, of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Steve Teutsch, MD, Diana Petitti, MD, Michael Lefevre, MD, and George Isham, MD, of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; Eric (Rocky) Feuer, PhD, of the National Cancer Institute; Evelyn Whitlock, Ph.D. the Oregon Evidence Based Practice Centerand Laura Seeff, MD, David Ransohoff, MD, and Carolyn Rutter, PhD.

Grant Support: By the National Cancer Institute (U01-CA-088204, U01-CA-097426, and U01-CA-115953) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HHSP233200700350P, HHSP233200700210P, and HHSP233200700196P).

Appendix : Model Descriptions

We used the MISCAN and SimCRC models from the National Cancer Institute's Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) to compare colorectal cancer (CRC) screening strategies that vary by the age to begin screening, the age to end screening, and screening interval. The use of two models (i.e., a comparative modeling approach) provides a sensitivity analysis on the model structure. While the models were developed independently, they were calibrated to the same data on adenoma prevalence and CRC incidence and they use the same assumptions regarding the sensitivity, specificity, and reach of the various screening tests. Accordingly, differences in findings across models may be attributed to differences in model structure and the assumptions about the natural history of CRC. Brief descriptions of the MISCAN and SimCRC model are provided below.

MISCAN Model

MISCAN overview. MISCAN-COLON is a semi-Markov microsimulation program to simulate the effect of screening and other interventions on colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and mortality. With microsimulation we mean that each individual in the population is simulated separately. The model is semi-Markov in the sense that:

- distributions other than exponential are possible in each disease state

- transitions in one state can depend on transitions in earlier states,

- transitions can be age and calendar time dependent

All events in the model are discrete, but the durations in each state are continuous. Hence, there are no annual transitions in the model.

MISCAN simulation of the natural history of CRC

The development of CRC in the model is assumed to occur according to the adenoma carcinoma sequence. This means that adenomas arise in the population, some of which eventually develop into CRC. We assume that there are two types of adenomas: progressive and non-progressive adenomas. Non-progressive adenomas can grow in size, but will never develop into a cancer. Progressive adenomas have the potential to develop into cancer, if the person in whom the adenoma develops lives long enough.

All adenomas start as a small (≤ 5 mm) adenoma. They can grow in size to medium (6-9 mm) and large (≥ 10 mm) adenoma. Progressive medium and large adenomas can transform into a malignant cancer stage I, not yet giving symptoms (preclinical cancer). The cancer then progresses from stage I (localized) eventually to stage IV (distant metastasis). In each stage there is a probability of the cancer giving symptoms and being clinically detected. An adenoma is assumed to take on average 20 years to develop into CRC and become detected by symptoms. However, because many adenomas do not progress to CRC before the person dies of other causes, the average time a lesion has been present before it is diagnosed as CRC is approximately 10 years. After clinical detection a person can die of CRC, or of other causes based on the survival rate. The survival from CRC is highly dependent on the stage in which the cancer was detected.

MISCAN simulation of an individual. Appendix Figure 1.1 shows how the model generates an individual life history. First MISCAN-COLON generates a time of birth and a time of death of other causes than CRC for an individual. This is shown in the top line of Appendix Figure 1.1. This line constitutes the life history in the absence of CRC. Subsequently, MISCAN-COLON generates adenomas for an individual. For most individuals no adenomas are simulated, for some multiple. In this example MISCAN-Colon has generated two adenomas for the individual. The first adenoma occurs at a certain age and grows in size from small to medium and large adenoma. However this is a non-progressive adenoma, so this adenoma will never transform into cancer. The second adenoma is a progressive adenoma. After having grown to 6-9 mm, the adenoma transforms into a malignant carcinoma, causing symptoms and eventually resulting in an earlier death from CRC.

Appendix Figure 1.1.

MISCAN and SimCRC Modeling Natural History into Life History

The life history without CRC and the development of the two adenomas are combined into a life history in the presence of CRC. This means that the state a person is in is the same as the state of the most advanced adenoma or carcinoma present. If he dies from CRC before he dies from other causes, his death age is adjusted accordingly. The combined life history with CRC is shown in the bottom line of Appendix Figure 1.1.

MISCAN simulation of screening. The complete simulation of an individual life history in Appendix Figure 1.1 is in a situation without screening taking place. After the model has generated a life history with CRC but without screening, screening is overlaid. This is shown in Appendix Figure 1.2. The first three lines show the combined life history with CRC and the development of the two adenomas from Appendix Figure 1.1. At the moment of screening both adenomas are present, detected and removed. This results in a combined life history for CRC and screening (bottom line), where the person is adenoma-carcinoma free after the screening intervention. Because the precursor lesion has been removed this individual does not develop CRC and will therefore not die of CRC. The moment of death is delayed until the moment of death of other causes. The benefit of screening is equal to the difference between life-years lived in a situation with screening and the situation with screening.

Appendix Figure 1.2.

MISCAN and SimCRC Modeling of Screening into Life History

Many other scenarios could have occurred. A person could have developed a third adenoma after the screening moment and could still have died of CRC. Another possibility would have been that one of the adenomas was missed, but in the presented example the individual really benefited from the screening intervention.

The effectiveness of screening depends on the performance characteristics of the test performed: sensitivity, specificity and reach. In the model, one minus the specificity is defined as the probability of a positive test result in an individual irrespective of any adenomas or cancers present. For a person without any adenomas or cancers, the probability of a positive test result is therefore equal to one minus the specificity. In individuals with adenomas or cancer the probability of a positive test result is dependent on the lack of specificity and the sensitivity of the test for the present lesions. Sensitivity in the model is lesion-specific, where each adenoma or cancer contributes to the probability of a positive test result.

The model provides the opportunity to consider the possibility of systematic test results.

SimCRC Model

SimCRC overview

The SimCRC model of CRC was developed to evaluate the impact of past and future interventions on CRC incidence and mortality in the U.S. The model is population-based, meaning that it simulates the life histories of multiple cohorts of individuals of a given year of birth. These cohorts can be aggregated to yield a full cross-section of the population in a given calendar year. For this analysis, we simulated the life histories of only one cohort—those aged 40 years in 2005. SimCRC is a hybrid model, specifically it is a cross between a Markov model and a discrete event simulation. While annual (often age-specific) probabilities define the likelihood of transitioning through a series of health states, the model does not have annual cycles. Instead, the age at which a given transition takes place for each simulated individual is drawn from a cumulative probability function.

SimCRC simulation of the natural history of CRC

The SimCRC natural history model describes the progression of underlying colorectal disease (i.e., the adenoma-carcinoma sequence) among an unscreened population. Each simulated individual is assumed to be free of adenomas and CRC at birth. Over time, he is at risk of forming one or more adenomas. Each adenoma may grow in size from small (≤ 5 mm) to medium (6-9 mm) to large (≥ 10 mm). Medium and large adenomas may progress to preclinical CRC, although most will not in an individual's lifetime. Preclinical cancers may progress in stage (I-IV) and may be detected via symptoms, becoming a clinical case. Individuals with CRC may die from their cancer or from other causes.

The SimCRC model allows for heterogeneity in growth and progression rates across multiple adenomas within an individual. While all adenomas have the potential to develop into CRC, most will not. The likelihood of adenoma growth and progression to CRC is allowed to vary by location in the colorectal tract (i.e., proximal colon vs. distal colon vs. rectum). Appendix Figure 1.1 shows how the SimCRC model constructs an individual's life history in the absence of screening for CRC.

SimCRC simulation of screening

The screening component of the SimCRC model is superimposed on the natural history model. It allows for the detection and removal of adenomas and the diagnosis of preclinical CRC (Appendix Figure 1.2). In a screening year, a person with an underlying (i.e., undiagnosed) adenoma or preclinical cancer faces the chance that the lesion is detected based on the sensitivity of the test for adenomas by size or for cancer and the reach of the test. Individuals who do not have an underlying adenoma or preclinical cancer also face the risk of having a positive screening test (and undergoing unnecessary follow-up procedures) due to the imperfect specificity of the test. While the model does not explicitly simulate non-adenomatous polyps, they are accounted for through the specificity of the test. Additionally, individuals with false-negative screening tests (i.e., individuals with an adenoma or preclinical cancer that was missed by the screening test) may be referred for follow-up due to the detection of non-adenomatous polyps. The model incorporates the risk of fatal and non-fatal complications associated with various screening procedures. It also accounts for the fact that not all individuals are adherent with CRC screening guidelines and that adherence patterns are correlated within an individual.

The SimCRC model incorporates treatment for invasive cancer such as adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and other improvements in cancer-specific mortality following diagnosis of CRC. Patients who are diagnosed with CRC, either by symptom detection or by a positive colonoscopy result, face a monthly cancer-specific mortality rate that is a function of the stage at diagnosis, age at diagnosis (<75 years, 75 years or greater), time since diagnosis, and We used the MISCAN and SimCRC models from the National Cancer Institute's Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) to compare strategies for colorectal cancer screening that vary by the age at which to begin screening, the age at which to end screening, and screening interval. The use of 2 models (that is, a comparative modeling approach) provides a sensitivity analysis on the model structure. Although the models were developed independently, they were calibrated to the same data on adenoma prevalence and colorectal cancer incidence, and they use the same assumptions regarding the sensitivity, specificity, and reach of the various screening tests. Accordingly, differences in findings across models may be attributed to differences in model structure and the assumptions about the natural history of colorectal cancer. Both models are described below.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: “This is the prepublication, author-produced version of a manuscript accepted for publication in Annals of Internal Medicine. This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The American College of Physicians, the publisher of Annals of Internal Medicine, is not responsible for the content or presentation of the author-produced accepted version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to this manuscript (e.g., correspondence, corrections, editorials, linked articles) should go to www.annals.org or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record.”

Reproducible Research Statement

Models are available to approved individuals with written agreement.

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest: None disclosed.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, Ries LA, Wu X, Jamison PM, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [PMID: 15221985] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts and Figures 2008. Accessed at www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/2008CAFFfinalsecured.pdf on September 15, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, Snover DC, Bradley GM, Schuman LM, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1365–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305133281901. [PMID: 8474513] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, Moss SM, Amar SS, Balfour TW, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348:1472–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [PMID: 8942775] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jørgensen OD, Søndergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996;348:1467–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. [PMID: 8942774] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, Godlee F, Stolar MH, Mulrow CD, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594–642. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.agast970594. [PMID: 9024315] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Gastrointestinal Consortium Panel. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544–60. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [PMID: 12557158] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for colorectal cancer: recommendation and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:129–31. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00014. [PMID: 12118971] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Whitlock in Annals of Internal Medicine, same issue.

- 10.Loeve F, Boer R, van Oortmarssen GJ, van Ballegooijen M, Habbema JD. The MISCAN-COLON simulation model for the evaluation of colorectal cancer screening. Comput Biomed Res. 1999;32:13–33. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1998.1498. [PMID: 10066353] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loeve F, Brown ML, Boer R, van Ballegooijen M, van Oortmarssen GJ, Habbema JD. Endoscopic colorectal cancer screening: a cost-saving analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:557–63. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.7.557. [PMID: 10749911] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Schrag D, Boer R, Winawer SJ, Habbema JD, et al. How much can current interventions reduce colorectal cancer mortality in the U.S.? Mortality projections for scenarios of risk-factor modification, screening, and treatment. Cancer. 2006;107:1624–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22115. [PMID: 16933324] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frazier AL, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS, Kuntz KM. Cost-effectiveness of screening for colorectal cancer in the general population. JAMA. 2000;284:1954–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.15.1954. [PMID: 11035892] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Surveillance Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program ( http://www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER* Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 9 Regs Public-Use, Nov 2003 Sub (1973-2001), National Cancer Institute. DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2004, based on the November 2003 submission.

- 15.Clark JC, Collan Y, Eide TJ, Estève J, Ewen S, Gibbs NM, et al. Prevalence of polyps in an autopsy series from areas with varying incidence of large-bowel cancer. Int J Cancer. 1985;36:179–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910360209. [PMID: 4018911] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blatt LJ. Polyps of the colon and rectum: incidence and distribution. Dis Colon Rectum. 1961;4:277–82. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vatn MH, Stalsberg H. The prevalence of polyps of the large intestine in Oslo: an autopsy study. Cancer. 1982;49:819–25. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820215)49:4<819::aid-cncr2820490435>3.0.co;2-d. [PMID: 7055790] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jass JR, Young PJ, Robinson EM. Predictors of presence, multiplicity, size and dysplasia of colorectal adenomas. A necropsy study in New Zealand. Gut. 1992;33:1508–14. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.11.1508. [PMID: 1452076] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johannsen LG, Momsen O, Jacobsen NO. Polyps of the large intestine in Aarhus, Denmark. An autopsy study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:799–806. doi: 10.3109/00365528909089217. [PMID: 2799283] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bombi JA. Polyps of the colon in Barcelona, Spain. An autopsy study. Cancer. 1988;61:1472–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880401)61:7<1472::aid-cncr2820610734>3.0.co;2-e. [PMID:3345499] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams AR, Balasooriya BA, Day DW. Polyps and cancer of the large bowel: a necropsy study in Liverpool. Gut. 1982;23:835–42. doi: 10.1136/gut.23.10.835. [PMID: 7117903] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rickert RR, Auerbach O, Garfinkel L, Hammond EC, Frasca JM. Adenomatous lesions of the large bowel: an autopsy survey. Cancer. 1979;43:1847–57. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197905)43:5<1847::aid-cncr2820430538>3.0.co;2-l. [PMID: 445371] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CHAPMAN I. Adenomatous polypi of large intestine: incidence and distribution. Ann Surg. 1963;157:223–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196302000-00007. [PMID: 14020146] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arminski TC, McLean DW. Incidence and distribution of adenomatous polyps of the colon and rectum based on 1,000 autopsy examinations. Dis Colon Rectum. 1964;7:249–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02630528. [PMID: 14176135] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, Ederer F, Geisser MS, Mongin SJ, et al. The effect of fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1603–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432203. [PMID: 11096167] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandel JS, Church TR, Ederer F, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer mortality: effectiveness of biennial screening for fecal occult blood. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:434–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.5.434. [PMID: 10070942] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Advisory Group Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [PMID: 18384785] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Fletcher RH, Stillman JS, O'brien MJ, Levin B, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:143–59. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.3.143. quiz 184-5. [PMID: 16737947] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zauber AG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Wilschut J, Knudsen AB, van Ballegooijen M, Kuntz KM. Cost-effectiveness of DNA stool testing to screen for colorectal cancer: report to AHRQ and CMS from the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) for MISCAN and SimCRC Models. Accessed at https://www.cms.hhs.gov/mcd/viewtechassess.asp?from2=viewtechassess.asp&id=212& September 15, 2008. [PubMed]

- 30.Mark DH. Visualizing cost-effectiveness analysis [Editorial] JAMA. 2002;287:2428–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.18.2428. [PMID: 11988064] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Rijn JC, Reitsma JB, Stoker J, Bossuyt PM, van Deventer SJ, Dekker E. Polyp miss rate determined by tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:343–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00390.x. [PMID: 16454841] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arias E. United States life tables, 2003. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2006;54:1–40. [PMID: 16681183] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown ML, Klabunde CN, Mysliwiec P. Current capacity for endoscopic colorectal cancer screening in the United States: data from the National Cancer Institute Survey of Colorectal Cancer Screening Practices. Am J Med. 2003;115:129–33. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00297-3. [PMID: 12893399] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mysliwiec PA, Brown ML, Klabunde CN, Ransohoff DF. Are physicians doing too much colonoscopy? A national survey of colorectal surveillance after polypectomy. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:264–71. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00006. [PMID: 15313742] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seeff LC, Manninen DL, Dong FB, Chattopadhyay SK, Nadel MR, Tangka FK, et al. Is there endoscopic capacity to provide colorectal cancer screening to the unscreened population in the United States? Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1661–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.052. [PMID: 15578502] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, et al. ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:873–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00673.x. [PMID: 16635231] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, Johanson JF, Greenlaw RL. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2533–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055498. [PMID: 17167136] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baron R, Rimer BK, Berkowitz J, Harris K, editors. Increasing Screening for Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Cancers—Recommendations from the Task Force on Community Preventive Services, Methods, Systematic Reviews of Evidence and Expert Commentary. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:A1–4. S1–76. [Google Scholar]