Abstract

Objective

We sought to determine whether individuals with schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes who smoke were being monitored and treated for modifiable risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease.

Methods

Cross-sectional analysis of 100 patients with schizophrenia and 99 without serious mental illness (SMI), with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

Results

Individuals with schizophrenia were nearly twice as likely to be smokers compared to those without SMI (62% vs. 34%). Among smokers, those with schizophrenia were significantly less likely to receive blood pressure exams, lipid profiles, or treatment with ACE inhibitors or statins compared to those without SMI. Both groups were equally likely to receive smoking cessation counseling.

Conclusions

Smokers with type 2 diabetes and schizophrenia are significantly less likely to receive services and treatments known to improve cardiovascular outcomes. Efforts to increase awareness and improve delivery of services to this vulnerable group of patients are warranted.

Background

Individuals with diabetes and severe mental illness (SMI) are at high risk for cardiovascular events.[1] Previous research suggests that those with diabetes and SMI are significantly less likely to receive recommended cardiovascular risk-reducing pharmacotherapy[2] and may receive lower quality of diabetes care [3-5]. Considering that smoking increases the risk for cardiovascular mortality among those with diabetes, [6] and those with SMI smoke at rates twice that of the general population [7;8] we sought to determine whether individuals with schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes who smoke were being monitored and treated for modifiable risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease.

Methods

Study Setting and Sample

Our data were collected as part of a larger cross-sectional investigation of individuals with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes which has been previously described.[9] The institutional review boards of the University Of Maryland School Of Medicine and of each participating facility approved the study.

Assessments have been previously described [9] but include demographic characteristics, medical service utilization and diabetes-related medical factors among others.

Outcome Measures

Cardiovascular care indicators

Medical charts were reviewed to assess whether participants received lipid assessment and blood pressure monitoring in the past year. Smokers were defined as participants who were currently smoking and smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Smokers were also asked if they received smoking cessation counseling from the diabetes provider.

Cardioprotective pharmacotherapy

Chart abstraction was used to document use of medications including cholesterol-lowering HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins), and blood pressure lowering agents--angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin-receptor blocking (ARB) agents.

Statistical Analysis

After stratifying individuals by current smoking status and diagnosis, indicators of quality of care for cardiovascular risk factors were examined. Services assessed included smoking cessation counseling, blood pressure and lipid monitoring, and prescription of ACEI or ARB agents and statins. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine the adjusted odds-ratios and 95% confidence intervals associated with the dependent variables listed above. Due to insufficient cell sizes, we were unable to perform logistic regression analyses for the blood pressure exam outcomes and we were unable to evaluate interactions. Statistical analyses were completed using SAS system (8.02). All reported p-values are two-sided.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The average age was 51 years, the majority were male, non-white, and had a high school education or greater. On average, the sample had elevated hemoglobin A1C's and were obese. Those with schizophrenia were significantly more likely to be a current smoker compared to those without SMI (61% vs. 34%, p=0.0003). Overall, 95% of the sample received blood pressure examinations, and 85% received lipid profiles. Twenty-seven percent reported being on a statin and 37% reported being on an ACE or ARB agent. Among those who smoked, 64% received smoking cessation counseling. (Table 1)

Table 1. Comparison of Demographic Characteristics, Cardioprotective Quality of Care Factors, and Medications Stratified by Smoking Status Among Those With Type 2 Diabetes With and Without Schizophrenia.

| Schizophrenia Non-Smokers (N=39) | Schizophrenia Smokers (N=61) | Non-SMI Non-Smoker (N=65) | Non-SMI Smokers (N=34) | Comparison between Schizophrenia Smokers and Schizophrenia Non- Smokers P-Value | Comparison between Schizophrenia Smokers and Non-SMI Smokers P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and Diabetes Related Factors | ||||||

| Age (Years±SD) | 48.1 (9.4) | 48.6 (8.7) | 54.8 (8.67) | 49.9 (8.4) | 0.76 | 0.49 |

| Male | 61.5% | 54.1% | 52.3% | 52.9% | 0.46 | 0.91 |

| White | 48.7% | 24.6% | 35.4% | 23.5% | 0.01 | 0.90 |

| HS Education | 74.4% | 62.3% | 63.1% | 73.5% | 0.21 | 0.27 |

| Duration of Illness | 6.7 (6.4) | 9.8 (8.5) | 7.4 (7.62) | 7.3 (6.8) | 0.05 | 0.14 |

| Hemoglobin A1C | 7.7 (2.1) | 7.9 (2.4) | 8.53 (2.33) | 8.9 (2.6) | 0.67 | 0.09 |

| BMI (kg/m2±SD) | 33.9 (6.4) | 32.0 (7.0) | 36.0 (6.86) | 32.8 (5.8) | 0.16 | 0.60 |

| History of Heart Problems | 23.1% | 22.9% | 28.8% | 18.2% | 0.99 | 0.56 |

| Use of Any Antipsychotic Medication | 98.4% | 97.4% | --N/A-- | --N/A-- | 0.75 | --N/A-- |

| Quality of care | ||||||

| Smoking Cessation Counseling | --N/A-- | 62.1% | --N/A-- | 79.4% | --N/A-- | 0.08 |

| Blood Pressure Exam | 100% | 86% | 96.7% | 100% | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Lipid Profile | 89.7% | 67.4% | 91.5% | 96.7% | 0.03 | 0.002 |

| Medication | ||||||

| Statins | 25.6% | 9.8% | 43.1% | 32.4% | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| ACE Inhibitors | 25.6% | 14.8% | 58.5% | 50% | 0.18 | <0.01 |

Cardiovascular Care Indicators

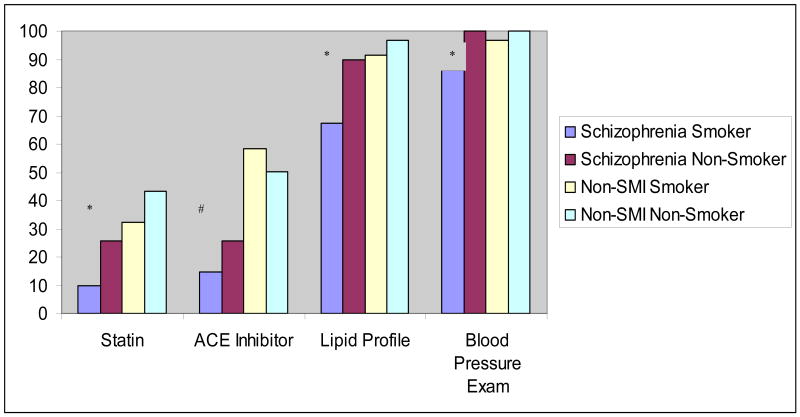

Those with schizophrenia who smoke were significantly less likely to have had blood pressure exams or lipid profiles compared to smokers without SMI as well as compared to non-smokers with schizophrenia (Figure 1). After adjusting for race, smokers with schizophrenia had 93% less the odds of a lipid profile compared to smokers without SMI (AOR [95% CI]; 0.07 [0.01-0.57]) and had 74% less the odds of a lipid profile compared to non-smokers with schizophrenia (AOR [95% CI]; 0.26 [0.07-1.00]).

Figure 1. Bar Graph Comparing Percent of Prescription for Statins and ACE inhibitors, as well as Reported Lipid and Blood Pressure Exams Stratified by Smoking Status among Those With Type 2 Diabetes With and Without Schizophrenia.

*= p<0.05 (X2 test) for comparisons between schizophrenia smokers and schizophrenia non- smokers as well as comparisons between schizophrenia smokers and non-SMI smokers.

#= p<0.05 (X2 test) for comparison between schizophrenia smokers and non-SMI smokers.

There was a trend toward those with schizophrenia being less likely to receive smoking cessation counseling compared to smokers without SMI (OR [95% CI]; (0.43 [0.12-1.12]), P=0.08).

Cardioprotective Pharmacotherapy

Those with schizophrenia who smoke were significantly less likely to receive a statin agent or an ACE inhibitor compared to smokers without SMI (Figure 1). After adjusting for race, smokers with schizophrenia had 77% reduction in the odds of receiving a statin compared to smokers without SMI (AOR [95% CI]; 0.23 [0.08-0.69]), 85% reduction in the odds of receiving an ACEI or ARB agent compared to smokers without SMI (AOR [95% CI]; 0.15 [0.06-0.43]), and a 72% reduction in the odds of receiving a statin compared to non-smokers with schizophrenia (AOR [95% CI]; 0.28 [0.09-0.89]).

Discussion

In our sample of adults with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes receiving diabetes care in community health care settings, we found that those individuals with type 2 diabetes and schizophrenia who smoke were significantly less likely to receive services and treatments known to improve cardiovascular outcomes. Other studies have shown disparities in diabetes care among those with diabetes and mental illness in VA populations [5], and in community clinics[3;4] as well as lack of metabolic monitoring in patients with schizophrenia receiving antipsychotics; [10] however, ours is the first to evaluate the potential additional impact of smoking. Smoking may affect delivery of medical care at the patient (e.g., non-adherence)[11], provider (e.g., competing demands) or system level.

This study has several limitations. First, because this is a cross-sectional study, we are limited to discussing associations rather than causality. Second, we were unable to determine whether or not patients actually received the prescribed medication. Third, we use chart diagnoses of schizophrenia. Fourth, we were not able to confirm actual diagnoses for hypertension or hypercholesterolemia. However, if there were prevalence differences among these disorders in our sample, we believe that those with schizophrenia would have a greater likelihood of having these disorders and suggest that our results may in fact underestimate the reported differences. Fifth, we did not quantify smoking using biological measures. Finally, the small sample sizes limited our ability to test interactions and may have put us at risk for a type 2 error particularly with respect to detecting a difference in receipt of smoking cessation counseling.

Previous research has shown that persons with schizophrenia have a life expectancy that is approximately 20% lower than the general population[12], with mortality rates attributed to cardiovascular disease more than any other cause [9;13;14]. Considering that smoking increases the risk for cardiovascular mortality among those with diabetes, and those with schizophrenia smoke at rates that are twice the general population, efforts to increase awareness and improve delivery of services to this vulnerable group of patients are warranted.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(8):e149–e161. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hippisley-Cox J, Parker C, Coupland C, Vinogradova Y. Inequalities in the primary care of patients with coronary heart disease and serious mental health problems: a cross-sectional study. Heart. 2007;93(10):1256–1262. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.110171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreyenbuhl J, Dickerson FB, Medoff DR, Brown CH, Goldberg RW, Fang L, et al. Extent and management of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes and serious mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(6):404–410. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000221177.51089.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg RW, Kreyenbuhl JA, Medoff DR, Dickerson FB, Wohlheiter K, Fang LJ, et al. Quality of diabetes care among adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(4):536–543. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frayne SM, Halanych JH, Miller DR, Wang F, Lin H, Pogach L, et al. Disparities in Diabetes Care: Impact of Mental Illness. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(22):2631–2638. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Leon J, Diaz FJ. A meta-analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking behaviors. Schizophr Res. 2005;76(23):135–157. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Himelhoch S, Daumit G. To whom do psychiatrists offer smoking cessation counseling? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2228–2230. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon LB, Kreyenbuhl JA, Dickerson FB, Donner TW, Brown CH, Wohlheiter K, et al. A comparison of type 2 diabetes outcomes among persons with and without severe mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(8):892–900. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissman EM, Zhu CW, Schooler NR, Goetz RR, Essock SM. Lipid monitoring in patients with schizophrenia prescribed second-generation antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(9):1323–1326. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shuter J, Bernstein SL. Cigarette smoking is an independent predictor of nonadherence in HIV-infected individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(4):731–736. doi: 10.1080/14622200801908190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman SC, Bland RC. Mortality in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia: a record linkage study. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;36:239–245. doi: 10.1177/070674379103600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osby U, Correia N, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Sparen P. Mortality and causes of death in schizophrenia in Stockholm county, Sweden. Schizophr Res. 2000;45(12):21–28. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212–217. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.3.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]