Abstract

Purpose

Comprehension deficits associated with right hemisphere brain damage (RHD) have been attributed to an inability to use context, but there is little direct evidence to support the claim. This study evaluated the effect of varying contextual bias on predictive inferencing by adults with RHD.

Method

Fourteen adults with no brain damage (NBD) and 14 with RHD read stories constructed with either high predictability or low predictability of a specific outcome. Reading time for a sentence that disconfirmed the target outcome was measured and compared with a control story context.

Results

Adults with RHD evidenced activation of predictive inferences only for highly predictive conditions, whereas NBD adults generated inferences in both high- and low-predictability stories. Adults with RHD were more likely than those with NBD to require additional time to integrate inferences in high-predictability conditions. The latter finding was related to working memory for the RHD group. Results are interpreted in light of previous findings obtained using the same stimuli.

Conclusions

RHD does not abolish the ability to use context. Evidence of predictive inferencing is influenced by task and strength of inference activation. Treatment considerations and cautions regarding interpreting results from one methodology are discussed.

Keywords: cognitive communication, stroke, language comprehension

It is widely accepted that right hemisphere brain damage (RHD) can cause difficulty with discourse comprehension. The underlying source of the comprehension deficits is not clear. One factor that has been implicated is the ability to use contextual cues. Adults with RHD are reported to have difficulty using context to generate inferences (Beeman, 1993; Purdy, Belanger, & Liles, 1992), predict upcoming events (Rehak et al., 1992), interpret connotative meanings (Schmitzer, Strauss, & DeMarco, 1997), and identify main ideas (Hough, 1990). However, other results suggest that adults with RHD can use context to assign pronouns (Leonard, Waters, & Caplan, 1997a, 1997b), generate inferences (Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005; Brownell, Potter, Bihrle, & Gardner, 1986; Lehman-Blake & Tompkins, 2001; Tompkins, Bloise, Timko, & Baumgaertner, 1994), interpret denotative meanings (Schmitzer et al., 1997), and identify direct and indirect requests (Stemmer, Giroux, & Joanette, 1994).

In a series of studies, Leonard and colleagues (Leonard & Baum, 1998, 2005; Leonard, Baum, & Pell, 2001; Leonard et al., 1997a, 1997b) examined whether or not adults with RHD were sensitive to semantic context. All studies included a group of individuals with RHD and a control group of adults with no brain damage (NBD). In the first two studies (Leonard et al., 1997a, 1997b), results indicated that adults with RHD were able to use semantic context to determine the antecedent for an ambiguous pronoun. Patterns of group performance did not differ between the RHD and control groups. A third study used a word-monitoring task to measure the effect of semantic context. Participants listened to either semantically normal sentences (e.g., “They were relieved to find that a store was near”) or semantically anomalous sentences (e.g., “They were impressed to feel that a store was gradual”). The RHD group demonstrated typical context effects, in which response times to target words (e.g., “store”) were faster for semantically normal sentences compared with anomalous sentences. The most recent two studies demonstrated that adults with RHD were sensitive to semantic context even under cognitively demanding conditions, such as compressed rate of speech (Leonard et al., 2001) and divided attention (Leonard & Baum, 2005). The studies in this series consistently support the idea that RHD does not abolish the ability to use contextual cues in sentences or two-sentence discourse stimuli.

The heterogeneity across research studies may be a key factor in the conflicting results. It is difficult to compare results across studies that differ in terms of (a) the type of language process examined (e.g., assigning pronouns, inferencing, interpreting nonliteral meanings); (b) the type of stimuli (including variable length, content, and complexity); and (c) the tasks, which may vary in terms of metacognitive, attentional, and memory demands.

Although use of context has long been used as a post hoc explanation of comprehension deficits, it has not often been specifically controlled or tested. The few studies that have directly manipulated context suggest that adults with RHD can use contextual cues to facilitate performance. Tompkins (1991) examined the ability to identify emotional inferences from short vignettes. In one condition, the vignettes contained two cues biasing toward a specific emotion. The other “redundant” condition contained the two cues plus a synonym of the target emotion, creating a strong contextual bias. Adults with RHD were more accurate at making emotional and prosodic judgments for the redundant versions than for the two-cue condition. Thus, they were able to use the additional contextual cue to facilitate performance. Nicholas and Brookshire (1995) also reported facilitation of comprehension with redundancy. Their Discourse Comprehension Test (Brookshire & Nicholas, 1993) measures comprehension of both details and main ideas. Details are defined as items mentioned only once within a story, whereas main ideas are defined as items that are repeated or elaborated upon several times within a story. The authors reported that adults with RHD, as well as those with brain damage due to traumatic brain injury or left hemisphere strokes, exhibited better performance on comprehension questions that targeted main ideas as opposed to details. As in Tompkins’ study, the presence of multiple cues facilitated performance.

Leonard and colleagues (1997b) manipulated contextual bias by using either strongly preferred or likely preferred referents for ambiguous pronouns. For example, in the stimulus “John spoke at a meeting while Henry drove to the beach. He brought his surfboard,” the strongly preferred referent for he is Henry. If the second sentence was changed to “He knocked over the water,” John would be the likely preferred referent for he. Adults with RHD demonstrated the same pattern as the NBD group, with faster reaction times for strongly than for likely preferred referents, indicating sensitivity to context.

Another controlled manipulation of context was used by Rehak and colleagues (1992), who examined generation of predictive inferences by adults with RHD. In their “suspense” story condition, a main cue that suggested a specific outcome appeared prior to the target event (e.g., an inspector did not conduct a trial run of a roller coaster even though it had been making suspicious noises the day before; on the first run, the roller coaster track broke). In the “surprise” version, the main cue appeared only after the event (e.g., later, after the accident, it was found that the inspector had not done the trial run). Rehak and colleagues reported that adults with RHD were able to predict specific outcomes that were supported by the suspense context and that the number of accurate predictions decreased when the supportive context was removed in the surprise versions. So yet again, the presence of contextual cues facilitated performance.

Blake and Lesniewicz (2005) addressed the impact of contextual bias on predictive inferencing using stimuli with varying contextual bias. The researchers employed a thinking-out-loud method to gather data about inferencing processes. Thinking-out-loud protocols have been used in the cognitive psychology literature to examine comprehension and other cognitive processes, including inferencing (Ericsson & Simon, 1980; van den Broek, Lorch, Linderholm, & Gustafson, 2001; Whitney, Ritchie, & Clark, 1991). The procedure involves asking participants to verbalize their thoughts while completing a task. The process places minimal extra cognitive demands upon participants and is thought to illuminate normal thought processes (Ericsson & Simon, 1980; Olson, Duffy, & Mack, 1984). The thinking-out-loud procedure allowed examination of several different aspects of inferencing including generation, maintenance, and likelihood of inferences (Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005). These factors were assessed in high-predictability texts that strongly suggested a single target outcome and in low-predictability texts in which several outcomes (including the target) were possible. Additionally, information about alternative predictions (other than the target inference) was collected. The results suggested that adults with RHD were able to use contextual cues to generate, maintain, and indicate the likelihood of inferences. Readers (both with and without RHD) were more likely to generate target predictive inferences in high-predictability than in low-predictability contexts. Similarly, the number of repetitions of a specific outcome (inference maintenance) and the likelihood of the inference (e.g., “He will steal the ring” vs. “He might steal the ring”) also varied logically according to contextual bias. Interestingly, the adults with RHD had difficulty using contextual cues to moderate inferencing processes: The RHD group generated the same number of alternatives for both high- and low-predictability contexts. Thus, in the high-predictability stories, they stated that one outcome was likely to occur and repeated that outcome several times but also generated multiple alternative predictive inferences. The authors concluded that although adults with RHD were able to use contextual cues to some extent, these individuals were not as effective at using context as were healthy older adults.

Tompkins and colleagues’ suppression deficit hypothesis (Tompkins, Baumgaertner, Lehman, & Fassbinder, 2000; Tompkins, Lehman-Blake, Baumgaertner, & Fassbinder, 2001; Tompkins, Lehman-Blake, Baumgaertner, & Fassbinder, 2002) provides a partial explanation for the findings from the thinking-out-loud study (Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005). This hypothesis suggests that adults with RHD are able to generate multiple possible interpretations licensed by a context but have difficulty suppressing those that are less appropriate, to allow efficient selection of the one most likely interpretation. The participants with RHD in Blake and Lesniewicz’s study clearly demonstrated the ability to generate multiple alternatives, and this was apparent for both high- and low-predictability stories. Examination of the thinking-out-loud responses indicates that in the high-predictability condition, NBD adults used contextual cues to prevent generation (or verbal expression) of alternative outcomes, whereas participants with RHD continued to generate alternatives in the presence of an increasing number of cues that supported the target outcome. Thus, it appears that there was a lack of integration of contextual cues to restrict continued generation of alternatives and not necessarily an inefficient suppression of those that were active (although the inefficient processes are not mutually exclusive).

The current study was designed to further evaluate effects of contextual bias on the generation of predictive inferences by adults with RHD. Although the previous thinking-out-loud study (Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005) provided some information, the nature of the task may have biased the results. First, the results were dependent on the participants’ verbal responses. Little or no information was obtained from the participants who did not verbalize all of their thoughts. Second, the instructions may have biased the results in the opposite direction. Participants were instructed to “talk about what you think will happen in the story.” Given those specific instructions, readers (with and without RHD) may have generated more predictions than they would during normal comprehension (Allbritton, 2004; Calvo, Castillo, & Schmalhofer, 2006). The current study used the same stimuli but with an online reading time task, in which inferencing was measured implicitly and participants were not specifically instructed to think about outcomes or predictions.

The reading time task was designed to elicit a contradiction effect. This effect is well established in the cognitive psychology literature as an indicator of inference generation (Albrecht & O’Brien, 1993; Fincher-Kiefer & D’Agostino, 2004; Klin, 1995; Klin, Murray, Levine, & Guzman, 1999). To elicit the effect, one sentence in the experimental stories contradicted or disconfirmed the intended predictive inference. For example, in a story that suggests that a man might steal a ring, the disconfirming sentence stated that he bought the ring. If readers generate a target inference, then reading times on a disconfirming sentence will be slowed as the readers attempt to integrate the conflict between the predicted outcome and the actual outcome. In a variety of studies, slowed reading has been reported on (a) target (disconfirming) sentences and (b) a sentence that immediately follows: the posttarget sentence (Albrecht & O’Brien, 1993; Calvo, 2000; Calvo & Castillo, 1996; Huitema, Dopkins, Klin, & Myers, 1993). The latter is referred to as a spill-over effect. There are several explanations of the source of spill-over effects (see detailed explanations in the companion article, this issue [Blake, 2009]). Briefly, the three explanations are (a) slowed inference generation, in which elaborative inferences (including predictive inferences) may take some time to be fully generated or instantiated (Calvo, 2000; Calvo & Castillo, 1996); (b) slowed selection or reactivation, in which target inferences are generated and instantiated earlier in a story but then are backgrounded by other information in the text and require some time to be selected or reactivated (see Blake, 2009); and (c) slowed/continued integration, in which target inferences are generated but some time is needed to integrate conflicting information into a mental model (Albrecht & O’Brien, 1993; Huitema et al., 1993).

The research question guiding the current study was whether adults with RHD can generate predictive inferences in high- and low-predictability contexts. The existing literature provides some direction for hypothesizing outcomes. Consistent with the results from Blake and Lesniewicz (2005) and previous work indicating that adults can generate elaborative inferences in the presence of a strong contextual bias (Blake, 2009; Lehman-Blake & Tompkins, 2001; Rehak et al., 1992) or multiple cues (Nicholas & Brookshire, 1995; Tompkins, 1991), it was expected that adults with RHD would generate inferences in the high-predictability contexts. Results from the previous thinking-out-loud study (Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005) indicated that adults with RHD generated target predictive inferences in low-predictability contexts. However, it was not known whether activation of the target inferences would be strong enough to be detected with the online measure. For example, if the reader generated three potential outcomes that were all considered equally likely, the target inference may or may not be activated strongly enough to make it stand out from the other inferences and be detected with the reading time measure (Linderholm, 2002).

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited for this study in combination with a study on maintenance of inferences. Readers can refer to the text and tables in the companion article (this issue; Blake, 2009) for details about the participants and recruitment procedures.

Stimuli

Stimuli were four short (10–15 sentences) stories that were written to have either high or low predictability of a specific outcome (the predictive inference). A sample is provided in the Appendix. The stimuli originally were used by Klin and colleagues (Klin et al., 1999) with young NBD adults. The stories were modified and validated for use with older adults (see Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005, for details). The target predictive inferences were “motivational” forward inferences such that they predicted an upcoming action but also provided a cause for a prior action. This type of predictive inference has been suggested to be more reliably generated by comprehenders without brain damage than predictive inferences that do not provide a causal link (Campion & Rossi, 2001; Klin et al., 1999).

Appendix.

Sample stimulus stories

|

HIGH predictability version (inference = steal) Brad was wandering through a department store, looking for a present for his wife’s birthday. He wanted to find something special for her. He had been laid off from his job three months ago and he couldn’t afford to buy anything nice. In the jewelry department he saw a beautiful ruby ring sitting in a display on the counter. The ring would thrill his wife, but there was no way he could pay for it. After making sure no one was watching, he quietly stepped closer to the counter. He smiled as he paid for the beautiful ring. It was going to be the perfect gift. Brad had decided to purchase the ring with a credit card. |

|

LOW predictability version Matt was wandering through a department store, looking for a present for his wife’s birthday. He wanted to find something special for her. He had just started a new job but had not received his first paycheck so he wasn’t sure he could buy anything nice. In the jewelry department, he saw a beautiful gold ring sitting in a display on the counter. The ring would thrill his wife, but he wasn’t sure he could pay for it. Not seeing any salespeople around, he quietly made his way closer to the counter. He smiled as he paid for the beautiful ring. It was going to be the perfect gift. Matt had decided to purchase the ring with a credit card. |

|

Control version Jeff was wandering through a department store, looking for a present for his wife’s birthday. He wanted to find something special for her. He recently received a big raise so he felt that he could afford to buy something nice. In the jewelry department, he saw a stunning ring sitting in a display on the counter. Knowing the ring would thrill his wife, Jeff wasn’t concerned about the price. In order to get a better view, he quietly stepped closer to the counter. He smiled as he paid for the beautiful ring. It was going to be the perfect gift. Jeff’s wife was thrilled with the ring. |

Note. Target (disconfirming) sentences are in bold; posttarget sentences are in italics.

There were three versions of each story: A high-predictability (HIGH) condition that suggested only one likely outcome (e.g., stealing a ring); a low-predictability (LOW) version in which the intended outcome (stealing) was one possible outcome but in which other outcomes were also possible (e.g., he would buy something other than a ring); and a control version that did not suggest any specific predictive inference.

The three versions of the stories across conditions contained the same number of sentences and had similar sentence structure. Names and other nonessential information varied across conditions to reduce the similarities between stories, as all participants read all versions of each story. The modifications were designed to lessen the chance that participants would make inferences based on another version of a story that they read in a previous session. Word frequency and familiarity differences across versions were minimized by repeating words or phrases that could trigger the target inference in different versions of a story (e.g., the phrases “have enough money,” “a ring sitting on the counter,”and “stepped quietly closer to the counter,”appear in each version of the story). Only one version of a story was presented in each testing session to reduce confusion among the versions. Participants were told that stories often sounded similar but were not exactly the same.

For the HIGH and LOW versions, the third-to-last sentence (target sentence) of each story disconfirmed the expected outcome to elicit the contradiction effect. The posttarget sentence of the experimental stories was neutral in regard to the predictive inference, neither confirming nor disconfirming the outcome. The purpose of the posttarget sentence was to assess the presence of a spill-over effect. The final sentence provided an explanation for the apparent contradiction.

Target and posttarget sentences were identical across the three versions of each stimulus to allow direct reading time comparisons. Thus, slowing was defined as reading the target/posttarget sentence in an experimental (HIGH or LOW) story more slowly than reading the same sentence in the control condition story.

Fifteen filler stories were interspersed with the experimental and control texts. The filler stories ended with a confirmed prediction. Taken together, 60% of the stimuli (fillers and control stories) contained no contradiction, whereas a contradiction appeared in the remaining 40% of the stimuli (HIGH/LOW conditions). To encourage participants to read for comprehension, two questions that probed details of the story were presented after all of the filler stories and after some experimental stories.

Procedures

Procedures for this study were similar to those used in the companion study (see Blake, 2009) and thus only a brief description and differences will be discussed here. Participants read stories one line at a time from a laptop computer screen. In the initial testing session, all participants completed at least 20 practice items. The extensive practice was provided to ensure that the participants were able to quickly read and progress through the stories so that the response times would accurately reflect reading times. Thus, for the first set of 10 practice stories, they were instructed to focus on pressing a response button “as soon as you finish reading each line.” The remaining practice items included comprehension questions to ensure that the participants comprehended the stories and were not simply moving through them quickly without understanding them. In subsequent sessions, participants completed 5 practice items as a reminder of the procedure and as a “warm-up.” The remaining procedures, including administration of ancillary tasks, are reported in the companion article (see Blake, 2009).

Results

Data Analysis

The study was conducted as a mixed design, with story condition (HIGH/LOW) and sentence type (target/posttarget) as a within-subjects factor and group (RHD/NBD) as the between-subjects factor. The dependent variables were reading time ratios for target and post-target sentences in experimental versus control conditions. Ratios were computed by subtracting control condition reading times from experimental condition reading times and then dividing by the control reading times (e.g., [Experimental – Control]/Control). The ratios were designed to reduce the effect of basic reading time on the results, given that the RHD group was generally slower than the NBD group. Positive ratios obtained from longer reading times for experimental than control versions indicated that inferences were generated in the experimental conditions. Higher ratios indicated greater slowing on experimental versus control conditions. Average reading times and ratios for each group are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean reading times (in seconds) and reading time ratios for two groups

| Condition and sentence type | NBD | RHD |

|---|---|---|

| Mean reading time (SD) | ||

| HIGH target | 2.87 (0.79) | 3.25(1.49) |

| HIGH posttarget | 2.28 (0.62) | 2.69(1.43) |

| LOW target | 2.58 (0.62) | 3.03(1.37) |

| LOW posttarget | 2.16(0.53) | 2.54(1.44) |

| Control target | 2.33 (0.46) | 2.88(1.37) |

| Control posttarget | 2.19(0.50) | 2.48(1.21) |

| Mean reading time ratioa (SD) | ||

| HIGH/Control target | .262 (0.246) | .122 (0.161) |

| HIGH/Control posttarget | .056 (0.113) | .095 (0.125) |

| LOW/Control target | .124 (0.149) | .048 (0.160) |

| LOW/Control posttarget | −.004 (0.095) | .054 (0.151) |

Note. NBD = no brain damage; RHD = right hemisphere brain damage; HIGH = high predictability; LOW = low predictability.

Calculated for individual participants as (Experimental − Control)/Control reading time.

A review of data was conducted to identify outlying data points and to examine comprehension. Reading times for target or posttarget sentences that were either two standard deviations above an individual’s mean reading time or less than 500 ms were deleted. This resulted in the loss of less than 1% of the data, spread approximately evenly across groups. Additionally, 1 NBD and 1 RHD participant were excluded from analyses due to reading times that were consistently greater than three standard deviations above their respective group mean. It was felt that these consistently long reading times may not accurately reflect initial reading processes but could also include rereadings or integration processes. Accuracy on the comprehension questions also was examined. To be included in the analyses, participants had to meet an a priori criterion of 80% accuracy. All participants met the criterion, with average accuracy of 95.5% for the NBD group (range = 90%–100%) and 90.4% for the RHD group (range = 81%–98%). Comprehension accuracy was not used in any other analyses.

Preliminary analyses were conducted to explore potential effects of extraneous variables. There was no effect of order of presentation, F(5, 23) < 1.0, p > .60, or of gender, t(27) < 1.6, p > .12. Thus, these variables were not considered further.

Group Analyses

A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with one between-subject factor and two within-subject factors was conducted on the ratio data. The between-subjects factor was group (NBD, RHD), and the within-subjects factors were condition ratios (HIGH/Control, LOW/Control) and sentence type (target, posttarget). Significant main effects were found for condition, F(1, 24) = 8.02, p =.009, η2 =.25; sentence type, F(1, 24) = 5.46, p =.028, η2= .19; and group, F(1, 26) = 27.47, p < .001, η2= .51. These results indicated that participants had higher reading time ratios (i.e., more slowing on experimental vs. control conditions) for HIGH (M = 0.13) than LOW (M = 0.06) conditions and higher ratios for target (M = 0.14) versus posttarget (M = 0.05) sentences. Additionally, the NBD group had higher ratios overall (M = 0.11) compared with the RHD group (M = 0.08).

There was a significant Group × Sentence type interaction, F(1, 24) = 4.32, p = .048, η2= .15, such that the NBD group had a large discrepancy between target and posttarget sentence ratios (target M =.19, posttarget M = .05), whereas the RHD group exhibited a minimal difference in ratios for sentence types (target M = .08, posttarget M = .07). The Group × Condition interaction was nonsignificant, F(1, 24) = 0.55, p = .46, η2= .02, as was the three-way Group × Condition × Sentence interaction, F(1, 24) = 0.24, p = .63, η2= .01.

Based on the research questions, four contrasts of interest were examined per group. To control for Type I errors in the within-group comparisons, the alpha level (p = .05) was divided by 4, so that significant results were defined as those with p values of less than .0125. Results indicated that for HIGH predictability stories, the NBD group evidenced slowed reading for the target sentences, t(12) = 3.85, p < .002, d = 2.2, but not for the post-target sentences, t(12) = 1.79, p = .10, d = 1.0. For the RHD group, results did not reach significance using the corrected p value for either the target sentences, t(12) = 2.72, p = .019, d = 1.6, or the posttarget sentences, t(12) = 2.76, p = .017, d = 1.6. However, the effect sizes for the RHD group were over 1.5, suggesting large effects. For the LOW predictability stories, the NBD group evidenced slowed reading for the target sentences, t(12) = 3.0, p = .011, d = 1.7, but not for the posttarget sentences, t(12) = −0.14, p = .90, d = −0.08. In contrast, the RHD group did not exhibit slowed reading for either the target sentences, t(12) = 1.07, p = .31, d = 0.61, or the posttarget sentences, t(12) = 1.3, p = .22, d = 0.75.

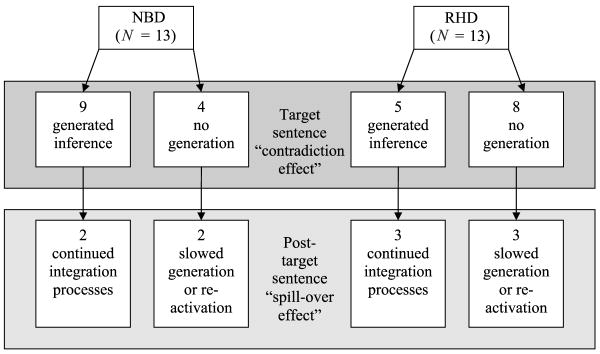

Individual Analyses

Individual analyses were conducted to examine how many participants followed their respective group pattern. Results are presented in Figures 1 and 2. Slowing was conservatively defined as reading times that were at least 5% slower for experimental versus control condition sentences (Lehman-Blake & Tompkins, 2001). Using this criterion, for the HIGH predictability stories, 12 of 13 participants in the NBD group and 9 of 13 participants with RHD evidenced slowed reading on the target sentence. Of those, 5 individuals with NBD and 6 with RHD exhibited continued slowing on the post-target sentence. The NBD results matched well with the significant effects from the within-group analyses, which indicated slowed reading only on the target sentences. For the RHD group, the results reflected the observed effect sizes from the within-groups comparisons, such that the majority of RHD participants (69%) demonstrated slowed reading on the HIGH predictability stories, and a majority of those (67%) also exhibited slowing (a spillover effect) on posttarget sentences for the HIGH predictability condition.

Figure 1.

Patterns of inference generation for two participant groups in a HIGH predictability condition. NBD = no brain damage; RHD = right hemisphere brain damage.

Figure 2.

Patterns of inference generation for two participant groups in a LOW predictability condition.

For the LOW predictability stimuli, 9 individuals with NBD and 5 with RHD evidenced slowed reading on the target sentence, which was consistent with the group analyses indicating an effect only for the NBD group on LOW predictability stimuli. Two individuals with NBD and 3 with RHD exhibited a spill-over effect, with continued slowing onto the posttarget sentence. Of those individuals without slowing on the target sentence, approximately half in each group (2 of 4 NBD and 3 of 8 RHD) exhibited slowing only on the posttarget sentence. Again, these results matched well with the within-group analyses, which indicated no significant slowing on posttarget sentences in the LOW predictability condition in either group.

Inferencing Correlates

To examine possible relationships between inferencing processes, working memory, and discourse comprehension, Pearson correlation coefficients were computed. Previous work has reported relationships for RHD but not NBD groups on correlates of performance (Tompkins et al., 1994, 2001); thus, separate correlations were computed for each group. Dependent variables were reading time ratios, working memory recall error scores, and Discourse Comprehension Test (DCT; Brookshire & Nicholas, 1993) total error scores. Prior to the analyses, visual inspection of the data revealed two outlying values for the DCT error scores. These 2 individuals (both with RHD) were excluded from the comprehension/inferencing correlations. For the NBD group, no meaningful or significant correlations were obtained (all rs < .5, all ps > .07). For the RHD group, there were no meaningful or significant correlations between inferencing and general comprehension (all rs < .4, all ps > .2). However, working memory recall was related to the slowed reading on the HIGH predictability condition posttarget sentences (r = .56, p = .04).

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate effects of contextual bias on adults with RHD, specifically to determine whether generation of predictive inferences would be affected by strength of contextual bias. Results indicated evidence of activation of target predictive inferences (slowed reading times) for high-predictability stories and for target sentences. Overall, the NBD group evidenced greater slowing than the RHD group. The within-group and individual participant analyses indicated that NBD participants activated target predictive inferences in both high- and low-predictability contexts. Some of these individuals required extra time to integrate an outcome that contradicted a highly predictive outcome. Adults with RHD evidenced activation of predictive inferences only in highly predictable contexts. Those with RHD who did generate inferences were likely to need extra integration time when faced with an outcome that contradicted the target outcome for both high-and low-predictability contexts.

Spill-Over Effects

The interpretation of the underlying source of spillover effects is addressed first, because these effects shed light on the primary inferencing processes and will facilitate the discussion of the influence of context. Spillover effects are obtained when participants are slow to read the posttarget sentence, indicating processing that either begins after or extends beyond the target sentence. As mentioned earlier, there are three proposed explanations of the spill-over effect: (a) slowed inference generation or instantiation, (b) slowed reactivation, and (c) slowed/continued integration. The first explanation, slowed inference generation, is not consistent with the data. In this account, slowing would be expected to occur in both high- and low-predictability contexts. Indeed, previous research suggests that the slowing should be more pronounced in low-predictability contexts, in which there is less support for a specific inference (Calvo, 2000; Calvo & Castillo, 1996). The current results show the opposite effect, however; individual analyses indicated that participants were more likely to demonstrate the spillover effect in the HIGH predictability conditions than in the LOW. Thus, the effect is not likely due to slowed generation or instantiation of predictive inferences.

The slowed reactivation explanation (see Blake, 2009) for spill-over effects purports that slowing should occur only on the posttarget sentence. This was seen only in 1 adult with RHD for the HIGH condition but was more common in the LOW condition. It is possible that in the LOW condition, individuals generated the target inference but also generated multiple others (similar to the findings reported by Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005). Then when the target sentence appeared, it took some time to reactivate the target inference, and thus the slowing was apparent only on the posttarget sentence. Slowed reactivation may be less likely to occur when contexts suggest a specific outcome (see Blake, 2009), precisely because there are few plausible alternative outcomes.

The third account of the spill-over effect purports that it is due to additional time needed to integrate or reconcile a contradiction (Albrecht & O’Brien, 1993; Huitema et al., 1993). This may explain results from individuals who demonstrated both activation of inferences on the target sentence and spill-over onto the post-target sentence. A majority of participants with RHD who generated a target inference exhibited continued slowing on the posttarget sentence for both HIGH and LOW predictability conditions. Some individuals in the NBD condition also demonstrated this continued activation but primarily in the HIGH predictability condition, in which the target inference was strongly suggested and strongly activated.

Inferencing and Contextual Bias

Adults without brain damage generated predictive inferences both in contexts that were biased toward one specific outcome and those in which several outcomes were possible. These participants were able to relatively quickly integrate conflicts between an actual outcome and their predicted outcome. A minority (13%) demonstrated slowed retrieval of inferences in LOW predictability conditions, suggesting that these individuals had initially generated the inference but took some time to reactivate it at a later time. These results are consistent with those obtained from the previous thinking-out-loud study (Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005).

Interpretation of the RHD results, based on the large effect sizes and patterns within the group, indicates a slightly different pattern of inferencing processes. Participants with RHD exhibited generation of predictive inferences only in highly predictive contexts. Many of those who generated the inferences required extra time to integrate actual outcomes with predicted outcomes. Some adults with RHD exhibited slowing only on the posttarget sentences, which may indicate reactivation of inferences, particularly in the low-predictability contexts that permitted several potential outcomes. Taken in isolation, the results from this study suggest that adults with RHD generate predictive inferences only in strongly biased contexts. The results appear to support previous accounts purporting that adults with RHD have difficulty using context and may be able to generate predictive inferences only in strongly biasing contexts (e.g., Beeman, 1993; Hough, 1990; Rehak et al., 1992). These conclusions are inconsistent with those reported by Blake and Lesniewicz (2005); this inconsistency was unexpected given that the same stimuli were used in both studies.

To facilitate the discussion of the apparently contradictory findings for the RHD group, a summary of the results from the current and previous studies (Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005) is provided in Table 2. As noted in the table, generation of inferences was measured in both studies. Data regarding integration processes were collected only in the current study. The likelihood of inferences, number of repetitions of a target inference, and number of alternative inferences were measured in the previous study.

Table 2.

Summary of results from two studies of predictive inferencing

|

Blake & Lesniewicz (2005) |

Current study |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | NBD | RHD | NBD | RHD |

| High-predictability stories | ||||

| Generated target inference | yes | yes | yes | yes* |

| Extra integration time needed | no | yes* | ||

| Likelihood of target inference | highly likely | highly likely | ||

| Number of repetitions of target inference | many | many | ||

| Number of alternate inferences generated | few | many | ||

| Low-predictability stories | ||||

| Generated target inference | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Extra integration time needed | no | no | ||

| Likelihood of target inference | somewhat likely | somewhat likely | ||

| Number of repetitions of target inference | some | some | ||

| Number of alternate inferences generated | many | many | ||

Effects were nonsignificant using a corrected alpha level, but effect sizes were large (d = 1.6) and the majority of participants demonstrated the effects.

Integrating findings from the current and previous (Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005) studies, one could paint the following picture: For high-predictability stories, adults with RHD generated target inferences (measured in both thinking-out-loud and reading time tasks). They suggested that the target outcome was highly likely to occur and repeated it several times while reading the story. This repetition served to boost activation of that inference and kept it active in working memory. Therefore, even though they did generate many alternative outcomes, the target inference was activated more strongly than the others due to the higher likelihood and repetition. Other alternatives, although initially generated, may not have remained in working memory, particularly in individuals with a reduced working memory capacity. The target inference, in contrast, was kept active in working memory through repetition.

The picture for low-predictability stories is not as clear. There were some individuals who did evidence target inference generation. The presence of subgroups within the larger RHD group has been reported in previous studies (e.g., Benton & Bryan, 1996; Joanette & Goulet, 1994; Lehman-Blake & Tompkins, 2001). Although the absence of individual analyses in many studies prevents accurate estimates of the extent of this phenomenon, it is likely to be widespread given the heterogeneity of this population. The lack of a cognitive-communication criterion for inclusion in the current study likely contributes to the findings of variability within the larger group. Exploratory analyses were conducted to examine potential effects of clinical or demographic variables, but as in previous studies, no significant results were obtained. However, these analyses were performed on small groups of uneven size, so the results are only tentative.

The more interesting question is what happened with those adults with RHD who did not evidence inference generation in the LOW predictability condition. Although adults with RHD did generate target inferences in the LOW predictability condition when specifically instructed to think about outcomes (Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005), they did not exhibit evidence of activation of those inferences in the reading time task. One explanation is that participants generated predictive inferences in the thinking-out-loud task because they were specifically instructed to do so. In contrast, in the current task, comprehension proceeded in a more natural fashion, which did not necessarily include thinking about potential outcomes. This explanation would require that adults with RHD were able to follow instructions to manipulate their comprehension processes but were not able to use contextual cues to facilitate comprehension. This may be possible if the participants were able to use the explicit instructions but not the implicit contextual cues. Further research is needed to examine this possibility.

A second explanation for the lack of a group effect for inferencing in the current LOW predictability condition is related to the strength of activation of inferences and working memory capacity. When reading the low-predictability stories, individuals with RHD generated the target inference, but it was considered only “somewhat likely” and may not have been activated very strongly. If the target inference was considered no more likely than the other many alternatives generated, then no one interpretation would stand out among the rest to create a strong contradiction with the disconfirming sentence (Linderholm, 2002). Additionally, the target inference was not frequently repeated. Without repetition, the activation was not increased. Also, without repetition, the inference may have been purged from working memory to allow room for new inferences. The many alternative inferences took up space in the restricted capacity of working memory, and without strong activation and/or repetition, the target inference was forced out by subsequently generated inferences. This would be consistent with the slowed selection/reactivation process, observed as a spill-over effect. When readers encountered the disconfirming sentence, the actual outcome (buy a ring) led them to reactivate a previously generated inference (steal a ring), if only to reject it or to note that it was erroneous. This could have caused slowing on the post-target sentence. This latter explanation is purely speculative and requires further testing. It is not known whether the actual outcome (in the disconfirming sentence) would stimulate reactivation of a specific previously generated inference, particularly when the actual outcome may also conflict with some of the alternative inferences generated (e.g., buy a card, not a ring).

Inferencing, Working Memory, and Discourse Comprehension

As previously suggested, a restricted working memory capacity may partially explain the results obtained. The correlations indicated that RHD participants with lower working memory scores tended to exhibit more slowing when reading the HIGH predictability condition posttarget sentences. These individuals may not have had enough working memory capacity to retain all of the potential outcomes generated while reading the stories (Linderholm, 2002), and thus the target inference was not active in working memory when the disconfirming sentence was encountered. The absence of a meaningful relationship between inferencing and working memory for the NBD group can be explained by Just and Carpenter’s (1987) capacity theory of comprehension. This account suggests that a certain level of working memory capacity is needed for comprehension processes. As long as that capacity is not exceeded, comprehension can occur with little problem. Thus, the NBD participants who did not exceed their working memory capacity were able to conduct inferencing processes without difficulty.

The absence of meaningful relationships between discourse comprehension and inferencing may be due to a variety of factors, including differences in the types of tasks. In particular, the DCT was not timed, allowing participants to reread the story as necessary until they felt ready to answer the questions. In contrast, speed was emphasized in the experimental task. Additionally, the DCT involves a memory component (remembering the story long enough to answer the questions), whereas the experimental task measured inferencing processes using a relatively online method.

Caveats

There are several caveats that must be taken into consideration in interpreting the current results. Several of these are related to the participants. First, the groups were relatively small, restricting generalization of results. Second, individuals in the RHD group were selected on the basis of a lesion in the right hemisphere and not the presence of cognitive-communication disorders. No formal cognitive-communication test battery was administered. One could conclude that the participants in the RHD group were mildly impaired, as all were living independently in the community, and potential participants were excluded on the basis of neglect due to the visual nature of the stimuli. Despite the assumption that they were mildly impaired, the group as a whole did exhibit typical deficits associated with RHD, including poorer performance (as compared with the control group) on measures of working memory, social inferencing, and comprehension of inferred details in discourse-level material.

Another important factor is that the measure of inferencing was indirect: Generation of the inferences was assumed based on slowed reading time. Although this is an established method of measuring inferencing in the cognitive psychology literature, it is not without its limitations. It is possible that the slowing did not reflect generation of the specific target inferences. The disconfirming sentences were designed to directly contradict the intended inference; however, they may also have conflicted with alternative inferences generated by the participants. Measures that use probe words to test activation of specific inferences, such as lexical decision or naming tasks, may shed more light on this issue.

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

The results of the current study, interpreted in light of the results from the thinking-out-loud study (Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005), suggest that adults with RHD used contextual cues and were sensitive to varying levels of contextual bias. Strong contextual biases lead to strongly activated inferences. Weaker contextual biases lead to more weakly activated inferences that may not be detected over the “noise” of other weakly activated inferences or that may be lost from working memory in individuals with restricted capacities.

One important finding from this study is that conclusions drawn from only one type of methodology must be considered with caution. If results from this study were taken in isolation, one might conclude that adults with RHD do not generate predictive inferences in weakly biasing contexts. However, when the results are combined with those from the previous study (Blake & Lesniewicz, 2005), the conclusions change dramatically: Adults with RHD do generate multiple predictive inferences. Activation of one specific inference may not be detected with online measures if no one interpretation is clearly preferred or considered more appropriate, or if the timing of the measurement does not allow for reactivation of a target inference.

Extending the findings to clinical applications, treatment should begin with the understanding that RHD does not eliminate the ability to use contextual cues or generate inferences. Results from various sources indicate that adults with RHD can and do generate multiple inferences licensed by a context. However, efficiency of inferencing processes may be influenced by working memory capacity and may impact discourse comprehension. Treatment should focus on evaluating contextual cues, determining which ones are relevant and which are not, and integrating multiple cues to arrive at one most plausible interpretation (see Blake, 2007).

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Grant R03-DC00563-01A1 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Kimberly Lesniewicz provided invaluable assistance in collection of the data.

References

- Albrecht JE, O’Brien EJ. Updating a mental model: Maintaining both local and global coherence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1993;19:1061–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Allbritton D. Strategic production of predictive inferences during comprehension. Discourse Processes. 2004;38:309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Beeman M. Semantic processing in the right hemisphere may contribute to drawing inferences from discourse. Brain and Language. 1993;44:80–120. doi: 10.1006/brln.1993.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton E, Bryan K. Right cerebral hemisphere damage: Incidence of language problems. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 1996;19:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake ML. Inferencing processes after right hemisphere brain damage: Maintenance of inferences. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52:359–372. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/07-0012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake ML. Perspectives on treatment for communication disorders associated with right hemisphere brain damage. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2007;16:331–342. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2007/037). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake ML, Lesniewicz K. Contextual bias and predictive inferencing in adults with and without right hemisphere brain damage. Aphasiology. 2005;19:423–434. [Google Scholar]

- Brookshire RH, Nicholas LE. Discourse Comprehension Test. Tucson, AZ: Communication Skill Builders; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell HH, Potter HH, Bihrle AM, Gardner H. Inference deficits in right brain-damaged patients. Brain and Language. 1986;27:310–321. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(86)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo MG. The time course of predictive inferences depends on contextual constraints. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2000;15:293–319. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo MG, Castillo MD. Predictive inferences occur on-line, but with delay: Convergence of naming and reading times. Discourse Processes. 1996;22:57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo MG, Castillo MD, Schmalhofer F. Strategic influence on the time course of predictive inferences in reading. Memory & Cognition. 2006;34:68–77. doi: 10.3758/bf03193387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campion N, Rossi JP. Associative and causal constraints in the process of generating predictive inferences. Discourse Processes. 2001;31:263–291. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson KA, Simon HA. Verbal reports as data. Psychological Review. 1980;87:215–251. [Google Scholar]

- Fincher-Kiefer R, D’Agostino PR. The role of visuospatial resources in generating predictive and bridging inferences. Discourse Processes. 2004;37:205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hough MS. Narrative comprehension in adults with right and left hemisphere brain damage: Theme organization. Brain and Language. 1990;38:253–277. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(90)90114-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huitema JS, Dopkins S, Klin CM, Myers JL. Connecting goals and actions during reading. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1993;19:1053–1060. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.19.5.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joanette Y, Goulet P. Right hemisphere and verbal communication: Conceptual, methodological, and clinical issues. Clinical Aphasiology. 1994;22:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Carpenter PA. The psycholinguistics of reading and language comprehension. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Klin CM. Causal inferences in reading: From immediate activation to long-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1995;21:1483–1494. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.21.6.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klin CM, Murray JD, Levine WH, Guzman A. Forward inferences: From activation to long-term memory. Discourse Processes. 1999;27:241–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman-Blake MT, Tompkins CA. Predictive inferencing in adults with right hemisphere brain damage. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2001;44:639–654. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/052). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CL, Baum SR. On-line evidence for context use by right-bran-damaged patients. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1998;10:499–508. doi: 10.1162/089892998562906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CL, Baum SR. Research note: The ability of individuals with right-hemisphere damage to use context under conditions of focused and divided attention. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2005;18:427–441. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CL, Baum SR, Pell MD. The effect of compressed speech on the ability of right-hemisphere-damaged patients to use context. Cortex. 2001;37:327–344. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70577-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CL, Waters GS, Caplan D. The use of contextual information by right-brain damaged individuals in the resolution of ambiguous pronouns. Brain and Language. 1997a;57:309–342. doi: 10.1006/brln.1997.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CL, Waters GS, Caplan D. The use of contextual information related to general world knowledge by right brain-damaged individuals in pronoun resolution. Brain and Language. 1997b;57:343–359. doi: 10.1006/brln.1997.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linderholm T. Predictive inference generation as a function of working memory capacity and causal text constraints. Discourse Processes. 2002;34:259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas LE, Brookshire RH. Comprehension of spoken narrative discourse by adults with aphasia, right-hemisphere damage, or traumatic brain injury. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 1995;4:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Olson GM, Duffy SA, Mack RL. Thinking-out-loud as a method for studying real-time comprehension processes. In: Kieras DE, Just MA, editors. New methods in reading comprehension research. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1984. pp. 253–286. [Google Scholar]

- Purdy MH, Belanger S, Liles BZ. Right-hemisphere-damaged subjects’ ability to use context in inferencing. Clinical Aphasiology. 1992;21:135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Rehak A, Kaplan JA, Weylman ST, Kelly B, Brownell HH, Gardner H. Story processing in right-hemisphere brain-damaged patients. Brain and Language. 1992;42:320–336. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(92)90104-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitzer AB, Strauss M, DeMarco S. Contextual influences on comprehension of multiple-meaning words by right hemisphere brain-damaged and non-braindamaged adults. Aphasiology. 1997;11:447–460. [Google Scholar]

- Stemmer B, Giroux F, Joanette Y. Production and evaluation of requests by right hemisphere brain-damaged individuals. Brain and Language. 1994;47:1–31. doi: 10.1006/brln.1994.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins CA. Redundancy enhances emotional inferencing by right- and left-hemisphere-damaged adults. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1991;34:1142–1149. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3405.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins CA, Baumgaertner A, Lehman MT, Fassbinder W. Mechanisms of discourse comprehension impairment after right hemisphere brain damage: Suppression and enhancement in lexical ambiguity resolution. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2000;43:62–78. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4301.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins CA, Bloise CGR, Timko ML, Baumgaertner A. Working memory and inference revision in brain-damaged and normally aging adults. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1994;37:896–912. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3704.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins CA, Lehman-Blake MT, Baumgaertner A, Fassbinder W. Mechanisms of discourse comprehension impairment after right hemisphere brain damage: Suppression in inferential ambiguity resolution. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2001;44:400–415. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/033). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins CA, Lehman-Blake M, Baumgaertner A, Fassbinder W. Characterizing comprehension difficulties after right brain damage: Attentional demands of suppression function. Aphasiology. 2002;16:559–572. [Google Scholar]

- van den Broek P, Lorch RF, Linderholm T, Gustafson M. The effects of readers’ goals on inference generation and memory for texts. Memory & Cognition. 2001;29:1081–1087. doi: 10.3758/bf03206376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney P, Ritchie BG, Clark MB. Working-memory capacity and the use of elaborative inferences in text comprehension. Discourse Processes. 1991;14:133–145. [Google Scholar]