Abstract

A principal component analysis (PCA) based on the sign of the second derivative of the surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) spectrum obtained on in-situ grown Au cluster covered SiO2 substrates results in improved reproducibility and enhanced specificity for bacterial diagnostics. The barcode generated clustering results are systematically compared to those obtained from corresponding spectral intensities, first derivatives and second derivatives for the SERS spectra of closely related cereus group Bacillus strains. PCA plots and corresponding hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) dendrograms illustrate the improved bacterial identification resulting from the barcode spectral data reduction. Supervised DFA plots result in slightly improved group separation but show more susceptibility to false positive classifications than the corresponding PCA contours. In addition, this PCA treatment is used to highlight the enhanced bacterial species specificity observed for SERS as compared to normal bulk (non-SERS) Raman spectra. The identification algorithm described here is critical for the development of SERS microscopy as a rapid, reagentless, portable diagnostic of bacterial pathogens.

Introduction

The atomistic specificity of vibrational Raman spectral signatures provides a powerful and effective method for chemical identification of both simple molecular species and as well as more complex biological structures. This property, in conjunction with the Raman scattering amplification resulting from the well-known surface enhancement effect observed for molecules in close proximity to nanostructured metal surfaces, has often be exploited for bioanalytical applications.1 For example, recently reported applications of surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) include glucose level monitoring2, viral cell identification3 and cancer gene sequence signaling.4 Motivated by both clinical applications and heightened biothreat concerns in this decade, several research groups have demonstrated SERS to be a potential experimental approach for the detection and identification of whole bacterial cells with species and strain specificity.5–19

SERS offers unique advantages with respect to other optical and non-optical techniques as a diagnostic method for bacterial infectious disease medicine. The enormous Raman signal enhancement permits the acquisition of SERS spectra from single bacterial cells on a time scale of seconds without the need for sample amplification by growth or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods and without the need for extrinsic labeling.11–13 Consequently, SERS-based bacterial identification can be achieved rapidly by minimally trained personnel and is less subject to contamination or amplification inhibitory factors than PCR approaches which rely on sample amplification. Only low incident laser power (1 – 5 mw) is required for SERS data acquisition due to the large Raman cross-section enhancement thus enabling the development of low cost, portable SERS platforms for point-of-care diagnostics. The near diffraction limited spatial resolution afforded by microscopy allows SERS sensitivity and specificity to be applicable for the analysis of bacterial mixtures. Given the micron scale size of bacterial cells, specific Raman signatures can be acquired for single organisms placed on strongly enhancing SERS substrates.11 Finally, the fluorescence “quenching”11 and enhanced bacterial specificity resulting from the substrate to scatterer distance dependence of the SERS effect are added advantages relative to non-SERS Raman spectroscopy.11 Thus, rapid, reagentless (SERS substrate aside) bacterial diagnostics acquired with minimal sample handling appears achievable via a SERS methodology.

A key component of any SERS based bacterial diagnostic platform is a data reduction protocol for accurate species/strain identification. Cluster based multivariate data analysis techniques have been exploited previously to demonstrate the potential for SERS9,10,14,19 and non-SERS Raman, and FTIR vibrational spectra20–28 to provide unique signatures for bacterial identification. These methods allow the reproducibility and the specificity of a given spectroscopic assay to be quantified and permit the determination of spectral classification within a priori library reference groups. Typically, principal component analysis (PCA) is employed to dramatically reduce the dimensionality of the large spectral arrays, maximize the spectral variances resulting from these input data arrays and provide a basis for subsequent supervised group identification procedures. PCA plots (2D and 3D), and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) dendrograms are convenient representations showing naturally occurring group memberships via these objective classification methods. Supervised techniques, such as discriminant function analysis (DFA) or linear discriminant analysis (LDA), which use PC clusters as inputs, have frequently been employed for bacterial identification schemes, particularly for non-SERS Raman analysis.24–28 Model training techniques based on genetic algorithm29 or artificial neural network30 approaches have been used much less frequently for vibrational bacterial specificity analysis. In previous multivariate analysis of SERS bacterial signatures,9,10,14,19 distinct species specific clusters were obtained by PCA although in some cases significant averaging was required to observe reliable differentiation via PCA/DFA treatments of SERS spectra probably arising from the heterogeneity of the enhancing SERS medium.9,10,14

In nearly all reported vegetative bacterial SERS studies, bacteria are pre-mixed with a Ag colloidal solution and then spotted or dried onto inert (glass) surface or bacteria are deposited onto a freshly precipitated Ag colloidal solution.5,6,9,10,14–19 The requirement of freshly prepared Ag colloidal solution limits the potential applications of a SERS based bacterial diagnostic employing such substrates. In contrast, we have shown that strongly enhanced, reproducible SERS spectra are obtained when bacterial cells are placed on an in situ grown, gold nanoparticle covered SiO2 substrate.11–13 A doped sol-gel hydrolysis procedure results in aggregates of gold 80 nm particles covering the outer surface of the SiO2 matrix. Currently, these substrates can be stored for more than three months without performance degradation thus enabling a portable SERS platform employing these substrates for rapid, point-of-care, pathogen diagnostics.

In our previous studies, we qualitatively demonstrated that SERS provides detailed species-specific spectra for a wide range of bacteria grown in laboratory media, suspended in water, and placed on the sol-gel grown SERS substrate.11–13 As a further step toward evaluating the performance of this substrate for use in a SERS based bacterial diagnostic platform, we describe in this report a method for bacterial identification via PCA, HCA or DFA multivariate statistical analyses. A second derivative based clustering approach, combined with the reproducibility provided by the in situ grown Au nanoparticle covered substrates, is shown here to result in excellent species and strain level clusters for bacterial identification in a group of closely related bacteria. Such a quantitative treatment also allows the diagnostic capabilities resulting from different SERS substrates to be compared. In addition, potential problems associated with the use of supervised DFA clusters leading to false positive identifications are illustrated.

Analysis of the SERS spectra of members of the cereus group of Bacillus bacteria, in particular B. anthracis (Sterne and Ames), B. thuriengensis and B. cereus, is the primary focus in this study. Interest in this group of closely related species derives from the effort to develop novel methods for the detection and identification of potential biothreat agents. In contrast to the often lethal consequences in humans resulting from infections with B. anthracis, B. cereus is a commonly found soil bacterium that can result in food poisoning and B. thuringiensis produces a protein toxic to insect larvae and is thus widely used as a biological pesticide. The capability of distinguishing between avirulent B. anthracis strains; B. anthracis Sterne, and B. anthracis Ames, and the genetically closely related B. cereus and B. thuringiensis species is demonstrated here. Despite the range of pathological effects manifested by these bacteria, genetic evidence has been used to argue that these organisms constitute a single species, attesting to the similarity and phylogenic proximity of these species.31 Thus, the ability to rapidly distinguish between these organisms, as well as between strains within this group, is a minimum requirement for a bacterial diagnostic testing for the causative agent of anthrax and should serve as a good test of the SERS specificity resulting from the Au nanostructured substrates and the multivariate data processing protocols employed here.

A clustering analysis is also used here to illustrate a crucial attribute of SERS as compared to other optical approaches for bacterial identification. Based on observed spectral differences, we have previously demonstrated that the spectral distinction between bacterial species derived from FTIR and normal Raman spectra is generally much smaller than the specificity obtained from SERS vibrational signatures.11–13 This effect is fundamentally attributable to the distance dependence of the mechanisms for SERS activity. Thus, PC cluster bacterial identification methods based on SERS spectra should exhibit enhanced specificity, as well as sensitivity, compared to FTIR or normal Raman spectra fingerprinting schemes. This additional important advantage of SERS for bacterial diagnostics is readily demonstrated by use of the clustering analysis described here and serves to highlight the effectiveness of SERS for microorganism detection and identification via optical approaches.

Experimental

Bacterial strains

The bacterial strains used in these studies, their sources and additional relevant genotypic descriptions are summarized in Table 1. Bacterial strains were grown in ~ 15 mL of LB (Sigma) broth, harvested during the log growth phase by centrifugation and washed five times with deionized Millipore water. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in 0.25 mL of water and 1μL of the resulting ~109/mL bacterial suspension was pipeted directly onto the SERS substrate for purposes of the data analysis described here. SERS measurements were made after about two minutes when nearly all the water had evaporated. Signal acquisition during this one to two minute period results in variable SERS signal intensities due to bacterial mobility and reduced bacteria-substrate surface interactions. In order to obtain non-SERS Raman spectra of bulk bacterial samples, bacteria were placed on KBr plates.

Table 1.

Summary of bacterial strains investigated by SERS

| Species | Strain ID | Relevant Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus thuringiensis | ATCC 35646 | Wild-type environmental isolate | ATCC |

| Bacillus cereus | ADL#830 | Strain T, wild-type prototrophic | A. Driks, Loyola U. Med. Ctr. |

| Bacillus anthracis | Sterne | pXO2− | Colorado Serum Co. |

| Bacillus anthracis | Ames 33 | pXO1− pXO2− | S. Leppla, NIAID35 |

| Bacillus anthracis | Ames 35 | pXO2− | S. Leppla, NIAID36 |

| Bacillus licheniformis | ATTC 9945 | Wild-type environmental isolate | ATCC37 |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis | ATCC 35797 | Wild-type strain 1717 | ATCC |

| Mycobacterium fortuitum | ATCC 35754 | TMC 1530; clinical isolate from human sputum | ATCC |

| Escherichia coli | ATCC 12435 | A lambda- derivative of E. coli laboratory strain K-12 | ATCC |

| Salmonella typhimurium | ATCC 14028 | Wild-type isolated from animal tissue | ATCC |

SERS substrate

All SERS spectra reported here were obtained using the in-situ grown, aggregated Au nanoparticle covered SiO2 substrate developed in our laboratory previously.11 Details concerning the production of these SERS active chips and the characterization of their performance for providing reproducible SERS spectra of bacteria have already been described.11–13 Briefly, a two stage reduction of a metal doped sol-gel results in small (2 – 15 particles) aggregates of monodispersed ~80 nm Au nanoparticles covering the outer layer of ~1mm2 SiO2 substrate. The slowest step in this production scheme is the second reduction step in very dilute NaBH4 which requires about 24 hours for the in situ growth of the Au nanoparticle clusters. The shelf life of these sol-gel based substrates is currently in excess of 90 days. Thus this SERS substrate combines attributes of the chemically produced colloids which result in large enhancement factors11–13 (104 –105 per bacterium) with solid state ease of use and reproducibility.

Data Acquisition

All of the spectra shown here were acquired with the RM-2000 Renishaw Raman microscope employing a 50x objective and excited at 785 nm. SERS spectra were obtained with incident laser powers in the 1 – 3 mw range in ~10 seconds of illumination time. The observed spectra resulted from ~10 – 20 bacterial cells within the field of view (~100 μm2). Spectral resolution was set to 3 cm−1 although the minimum width for an observed bacterial spectral feature was 5 cm−1 (FWHH). The 520 cm−1 band of a silicon wafer was used for frequency calibration. Non-SERS spectra of bacteria were acquired with 60 seconds of 300 mw of incident 785 nm power.

Data Analysis

Initially, an automated curvature-based procedure was applied to eliminate spurious cosmic ray contributions to the SERS spectral signatures. For purposes of bacterial identification, all SERS spectra were subsequently Fourier filtered to remove high frequency noise components from the observed spectra. The multivariate data analysis was carried out with MatLab software subroutines. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on normalized spectra, first derivative spectra and second derivative spectra in the 500 cm−1 to 1600 cm−1 range. Input arrays were splined to 1 intensity value per cm−1. In another cluster method employed here, binary barcodes based on the sign of the second derivative of the spectrum were generated as input to the PCA clustering algorithms. A minimum value, typically at ~10% of the maximum second derivative value, was used as a threshold for the zero (one) assignment. This cutoff value was determined empirically and used without change throughout these studies. Mean centering the input spectral data did not affect the outcome of the clustering results described here. The PCA reduced data sets were used as inputs to hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) procedures. Both Ward’s algorithm and squared distances were used to evaluate the member dissimilarity for the HCA procedure. HCA results were summarized by corresponding dendrograms. Dendrograms shown here were constructed using member distances directly in order to display the large dynamic range of branching points resulting from the branching of the well separated tightly packed groups. The resulting principal components were inputs to a discriminant function analysis (DFA) as well. The Discriminant Partial Least Squares 2 (DPLS2) algorithm was used in creating the discriminant functions.32 Since the DFA space results from a rotation of the selected PCA subspace, each DF is simply a linear combination of these inputed PCs. Only the PCs carrying the most significant variance of a given data set, typically up to 98%, were used in the DFA treatments discussed here.

Results and Discussion

Cluster Analysis of Cereus Group SERS signatures

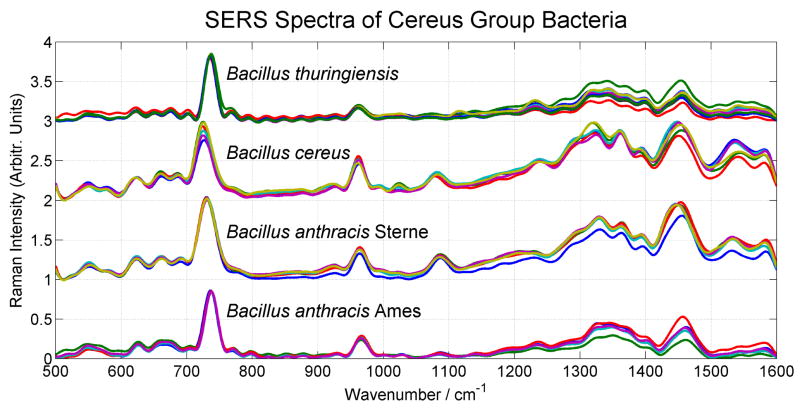

Multiple SERS spectra of four strains of the cereus group of Bacillus bacteria, B. anthracis Sterne, B. anthracis Ames 33, B. cereus and B. thuringiensis, in the 500 cm−1 to 1600 cm−1 range, normalized by the largest spectral intensity of each spectrum, are shown in Fig. 1. The degree of spectral (intensity, frequency and band shape) variability for a given species due to both SERS substrate and the bacterial cell inhomogeneities, is evident in this figure. Spectra for a given species were acquired on different in situ grown Au nanoparticle covered SiO2 substrates for a given isolate. As noted previously11, SERS spectra of bacteria on the gold nanoparticle covered substrates exhibit very similar and often analogous spectral features, such as the strong bands at ~730 cm−1, 960 cm−1, 1090 cm−1, and 1450 cm−1. The pattern of these vibrational bands is qualitatively similar in all the SERS spectra of these closely related cereus group bacteria and constitutes a rigorous test of multivariate data reduction methods for species/strain specific bacterial diagnosis. The SERS spectra of B. anthracis Sterne and B. cereus appear to be nearly homologous while the B. thuringiensis and B. anthracis Ames 33 SERS spectra appear to be very similar. Interestingly the empirical differences between the two anthracis strains (Ames 33 and Sterne) SERS spectra are more evident than those between the SERS spectra of different species within this set of spectral data (See Fig. 1). Much of B. anthracis virulence is extracellular and is controlled by genes on two plasmids, pX01 (encoding the secreted proteins protective antigen, lethal factor end endema factor) and pX02 (encoding the cell surface poly-D-glutamic acid capsule).33 As summarized in Table 1, the two B. anthracis strains studied here each contain different complements of the two virulence plasmids.

Figure 1.

Normalized SERS spectra of four members of the cereus group of bacillus bacteria: B. cereus, B. thuringensis, B. anthracis Sterne and B. anthracis Ames 33 acquired on a Au nanopaticle covered SiO2 substrate.

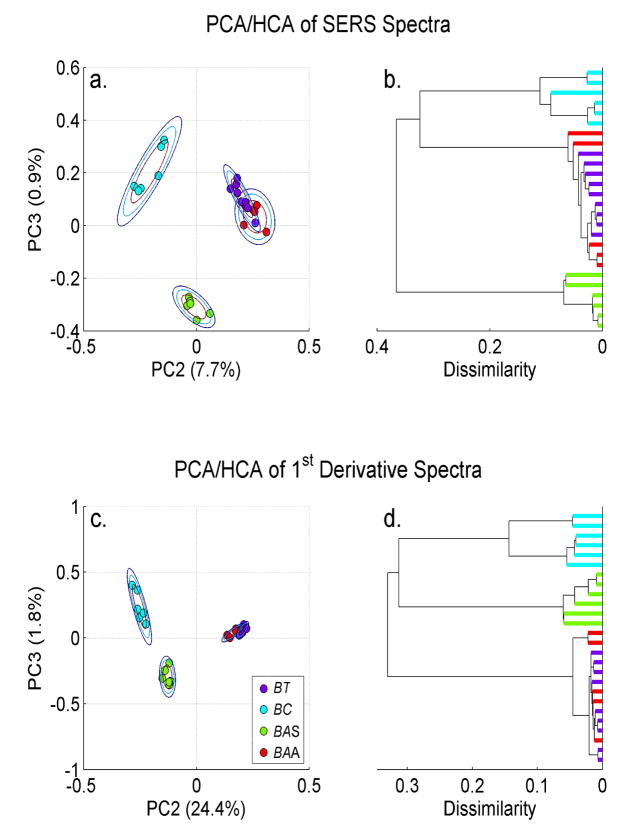

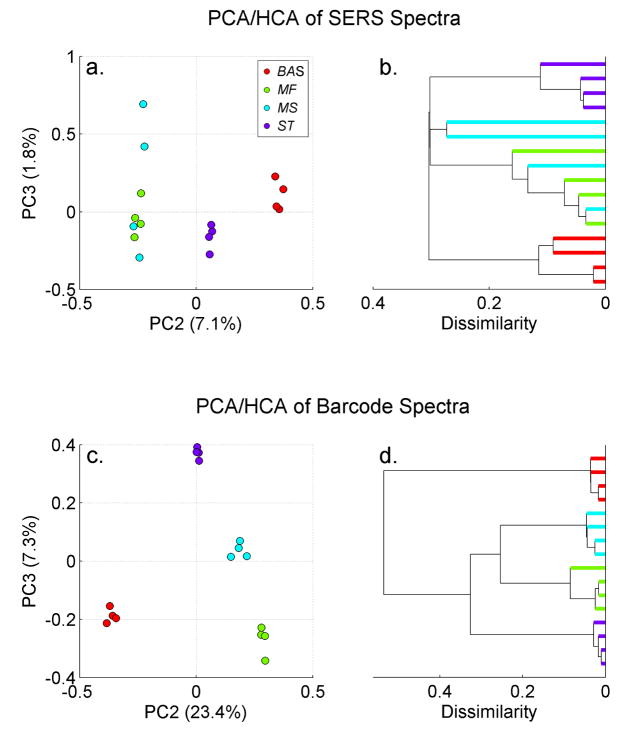

A series of PCA plots and the corresponding HCA dendrograms, resulting from different treatments of the cereus group SERS spectra shown in Fig. 1 are compared in Figs. 2a–2d and 3a –3d. For all the PCA results shown here we have plotted PC3 vs. PC2. This is generally the 2D contour in PC space that exhibits the greatest cluster separation at the highest level of significance. The percent variance captured by each of these principal components is indicated in parenthesis along the corresponding PCA axis. In addition, for each clustered species, three two-dimensional Gaussians have been drawn centered on the average value of a clustered group. Each resulting ellipse corresponds to a standard deviation for the PCA values of that distribution. These rings are a representation of the reproducibility of the data and offer a quantitative measure of the significance of the distance between clusters of different species/strains. In principle such standard deviation rings can be used as one measure of the diagnostic specificity offered by different substrates or alternative multivariate clustering strategies.

Figure 2.

PCA plots (PC2 vs. PC3) and the dendrograms corresponding to a HCA treatment of these PCA clustering results for the indicated cereus group bacterial SERS spectra based on: a. (b.) spectral intensities, c. (d.) first derivative spectra. Each cluster ring is a two dimensional standard deviation.

Figure 3.

PCA plots (PC2 vs. PC3) and the dendrograms corresponding to a HCA treatment of these PCA clustering results for the indicated cereus group bacterial SERS spectra based on: a. (b.) second derivative spectra and c. (d.) second derivative based barcodes (see text for details). DFA plot and HCA dendrogram corresponding to barcode treatment the four cereus group SERS data. (DF1 = 0.0336PC1 − 0.9953PC2 + 0.0138PC3 − 0.0902 PC4 + 0.5941PC5; DF2 = 0.1083PC1 − 0.1000PC2 − 0.7869PC3 + 0.0026PC4 − 0.0783PC5)

As evident in the PC3 vs. PC2 plots shown in Fig. 2, the PCA analysis based on the normalized spectral intensities (Fig. 2a) or the first derivative (Fig. 2c) of the SERS spectra of these four strains, show well-separated distinct B. anthracis Sterne and B. cereus clusters, but B. anthracis Ames 33 and B. thuringiensis are substantially overlapped. The corresponding distance based HCA dendrograms (Figs. 2b and 2d) convey this same assignment difficulty in the grouping of the B. anthracis Ames 33 and B. thuringiensis for the SERS spectra of the intensity and first derivative spectra. Ames 33 and thuringiensis cannot be separately classified in these HCA dendrograms. Again, it is interesting to note that within this data set the two B. anthracis strains (Ames 33 and Sterne) are judged to be more distinct than the B. anthracis Ames and B. thuringiensis species on the basis of these SERS fingerprints. The results imply that that the latter pair shares a greater similarity of cell surface features than does the former pair of strains.

In contrast, when the SERS spectra second derivatives, which highlights the shape of the peaks and troughs of the spectra, are used as input vectors for the correlation coefficients of the PCA treatment, improved cluster separation is obtained for this group of species in the PC2 vs. PC3 plane, as seen in Fig. 3a. The correct identification grouping of these spectra is evident in the corresponding HCA dendrogram (Fig. 3b) as well. These SERS derived input vectors Thus, the shape of the peaks and valleys of this SERS signature appears to offer a more bacteria-specific fingerprint than that due to either the peak intensities (Fig. 2a) or slopes (Fig. 2c) of the spectral features.

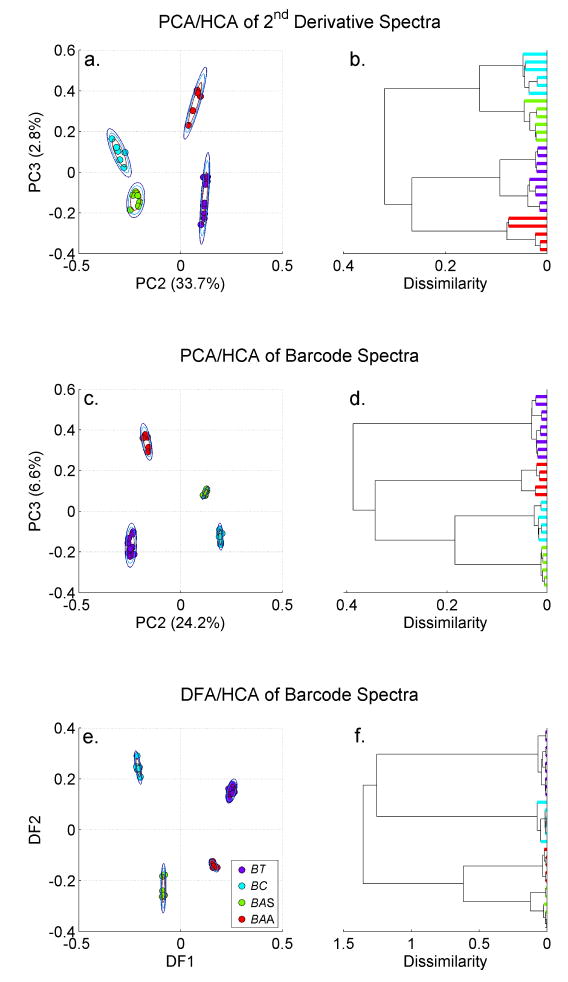

However, the best clustering results derived from the SERS bacterial spectra are consistently obtained when second derivative based barcodes are used as input vectors for the PCA treatment. As described above, when barcodes are assigned on the basis of the second derivative sign, i.e. +1 for upward curvature, (positive second derivatives) and 0 for downward curvature (negative second derivatives), each species is represented by a frequency dependent binary fingerprint. A threshold for zero, usually set at about 10% of the maximum value of the second derivative, is used to determine a minimum value for a 0 bit assignment for this barcode. This threshold helps discriminate against residual noise components. Such second derivative barcodes for the four Bacillus species of interest here are shown in Fig. 4. As seen in this figure, averaged barcodes for each of the species of interest here exhibit a unique SERS based signature. The resulting barcode PCA plot for these closely related Bacillus strains is shown in Fig. 3c. PC clusters corresponding to each of the four Cereus group bacteria derived from the second derivative barcode reduced SERS spectra data are well defined and separated from one another. The intragroup distances are minimized and the intergroup separations are maximized via this barcode PCA treatment relative to intensity, first or second derivative based PCA results. (Compare Figs. 2a, 2c, 3a, 3c.) Furthermore, the two-dimensional Gaussian contours shown in Fig. 3c reveal that many standard deviations (> 10) separate the four species in the barcode based PCA plot (Fig. 3c). In an alternative display of the specificity afforded by this barcode approach normalized spectra, (range) normalized first and second derivative spectra and barcodes of the four Bacillus strains were subject to a PCA clustering treatment. (See Supplementary Information.) In this normalized data test the barcode-reduced SERS spectra are shown to provide widely separated classification clusters at the highest levels of significance as compared to comparably normalized spectra or derivative spectra.

Figure 4.

Averaged barcodes derived from the SERS spectra shown in Fig. 1 for each of the indicated bacterial samples. For second derivatives < .007 the array spectral point is assigned a value of +1; otherwise the array point is 0 for the shown barcode. Averaged spectra are overlayed with the corresponding barcode.

Dendrogram derived from HCA calculations (Fig. 3d) also illustrates the success of this barcode approach as compared to the clustering derived from intensity, first derivative or second derivative based spectra (Figs. 2b, 2d, 3b). Not only are all the spectra properly classified according to species/strain in the barcode based HCA dendrogram (Fig. 3d), but the branching point for the members of a given species/strain type consistently occurs at smaller dissimilarity scores while the dissimilarity score is a maximum for the different strains in this dendrogram as compared to the other PCA derived dendrograms for this same initial set of SERS spectra (Figs 2b, 2d, 3b). The HCA dedrograms given here are based on distances in the PC3 vs. PC2 plane only. However, more dimensions (up to the PC dimensionality) could in principle be used to construct dendrograms for identification purposes. Using a convenient unsupervised strategy, all the PCs weighted by their significance were used to construct dendrograms for the data sets employed here. Due to the relatively small number of groups (4) and the quality of the PC3 vs. PC2 clustering results, the weighted PC dendrogram did not result in superior cluster differenctiation for the dat sets considered here. (See Supplementary Information.)

The PCA generated clusters were also employed in a supervised classification algorithm. The results of a discriminant function analysis (DFA) based on PCs derived in the barcode clustering procedure are shown in Fig. 3e. Only the PCs of greatest significance were retained for this DF1 vs. DF2 plot. For the data shown here, these discriminant functions consisted of linear combinations of the first five PCs and were dominated by the contribution of a single PC (See Fig. 3 caption for detailed DF1, DF2 description.) Due to the high quality of the unsupervised PCA results, only a very modest improvement in the cluster grouping is seen the in the resulting DFA results. Species/strain cluster separation is slightly larger in the DFA plot (Fig. 3e) than in the corresponding PCA result (Fig. 3c) and the dissimilarity scores are nearly all smaller in the HCA dendrograms derived from the DFA results (Fig. 3f) as compared to the corresponding PCA HCA results (Fig. 3d).

The specificity and reproducibility that typically results from the use of the barcode representation of the SERS bacterial data acquired on the gold nanoparticle covered substrates is additionally demonstrated in Fig. 5. A PCA plot of SERS spectra and the corresponding second derivative barcode representation of the SERS spectra are contrasted in this figure for four bacterial species; M. fortuitum, M. smegmatis, S. typhimurium and B. anthracis Sterne. The dramatically improved clustering and interspecies cluster distance enhancement resulting from the use of the barcode treatment of the SERS data is evident in this figure (compare Fig. 5a and b with Fig. 5c and d). These results and the more extensively described Cereus group analysis described above, are typical for the SERS bacterial spectra acquired on the gold nanocluster covered SERS substrates and thus indicate that a PCA/DFA scheme based on the barcode reduced SERS signatures provides the best analysis protocol for bacterial identification, at least compared to the other input vector strategies discussed here.

Figure 5.

PC2 vs. PC3 PCA contour for the SERS spectra of Bacillus anthracis Sterne, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium smegmatis and Salmonella typhimurium. Each cluster ring is a two dimensional standard deviation.

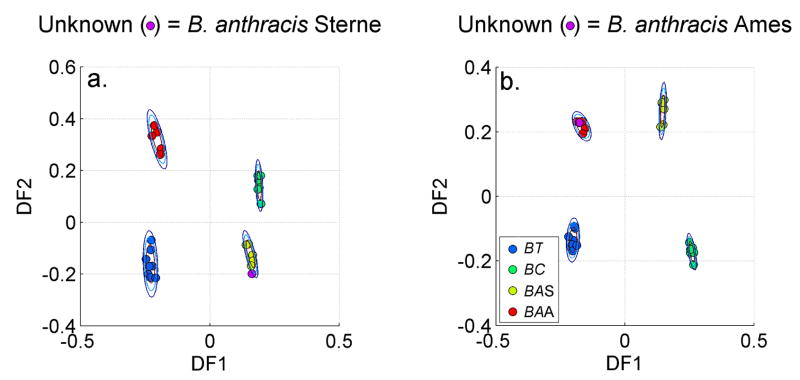

Examples of bacterial identification: in-class and out-of-class membership

Given the high quality of the PCA-DFA plots based on the second derivative sign, the identification of in-class membership demonstrated with a leave-one-out strategy employing the PCA or DFA vectors derived from the barcode data training set is virtually assured for the SERS data shown in Fig. 1. Two examples of positive identification using a B. anthracis Ames 33 and a B. anthracis Sterne SERS spectrum are demonstrated by the results shown in Fig. 6. DFA training sets derived from the n-1 spectral signatures are given in Figs. 6a and b (n is the total number of spectra in Fig. 1). The above-described second derivative based barcodes are used as input vectors for the PCA data reduction. When the PCs determined from the barcodes of the unknowns are projected into the DFA space they each fall in the correct Bacillus anthracis strain cluster for their identification. Note that the DFA plots are slightly different for these two examples (Figs. 6a and 6b) because the training sets differ by one member.

Figure 6.

Positive identification of a. B. anthracis Stern and b. B. anthracis Ames SERS signature is demonstrated via DFA plots of the cereus group SERS barcode training set.

Perhaps the more rigorous test of this clustering based procedure for bacterial identification is the ability to discriminate against out-of-class species or false positive bacterial classifications. Clearly avoiding such misclassifications is just as significant for the success of an identification scheme as a correct positive identification grouping. In Figs. 7, we contrast the ability of the PCA and DFA cereus group clustering results discussed above to discriminate against 3 different out-of-class unknowns: E. coli, B. licheniformis and B. anthracis Ames 35. This group tests the ability of the PCA/DFA clusters of B. anthracis Sterne, B. anthracis Ames 33, B. cereus and B. thuringiensis to demonstrate out-of-class or non-members from another genus, the same genus and another closely related strain. In Figs. 7a, 7c and 7e the PCA PC2 vs. PC3 plots are shown resulting from inclusion of each of these unknowns: E. coli, B. licheniformis and B. anthracis Ames 35, respectively. In each case the unknown does not find a match with any of the known clusters displayed. The unknowns are more than 10 standard deviations away from any group cluster mean coordinates for these PCA contours. Interestingly, the Ames 35 SERS spectrum has the same PC3 value as Sterne but the same PC2 as Ames 33 (Fig. 7e). Ames 35 is a descendent of the Ames genotype but is missing the same virulence plasmids as Sterne does (see Table 1). The PCA SERS plot for this strain seems to reflect these genetic factors.

Figure 7.

Out-of-group membership, i.e. false positives, are demonstrated for barcode based PCA and DFA plots of the four cereus group bacteria (B. anthracis Sterne, B. anthracis Ames 33, B. cereus and B. thuringiensis). The out-of-group unknowns are: a. (b.) E. coli; c. (d.) B. licheniformis; and e. (f.) B. anthracis Ames 35.

In Figs. 7b, 7d and 7f the results of projecting the PCs for the unknown into the DFs generated by the training set that does not include the unknown, are displayed in DF1 vs. DF2 plots. The most significant observations is that the B. licheniformis spectrum nearly clusters with the B. anthracis Sterne grouping (Fig. 7d). The DFA vectors which are linear combinations of the selected PCs, have been determined in order to maximize the distance between different groups and minimize the distance between intragroup members. In contrast, the unsupervised PCA treatment maximizes the variance between all the members of the input data set. Consequently, the rotation of PCs that results in DFs, may coincidently result in a linear combination of PCs that locates an unknown in an incorrect cluster. Clustering that is dependent on supervised methods such as DFA in order to achieve reliable specificity runs the risk of false positive identifications as shown here. Thus, unsupervised multivariate approaches which result in well-clustered groupings seems to offer the best chance for avoiding potential false positive identifications.

Species specificity of SERS vs. NonSERS Raman

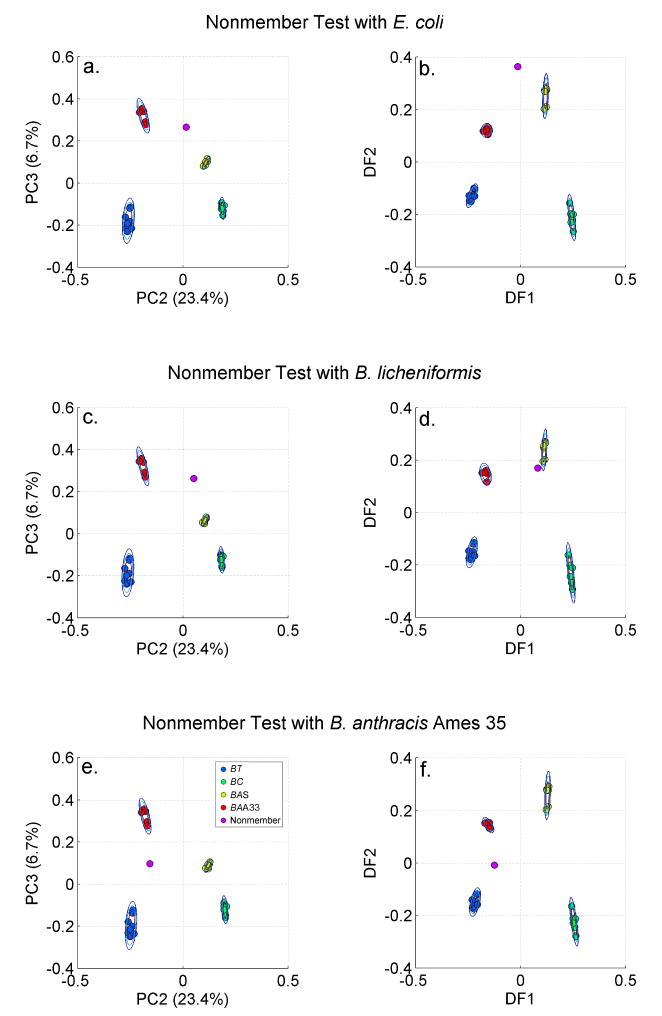

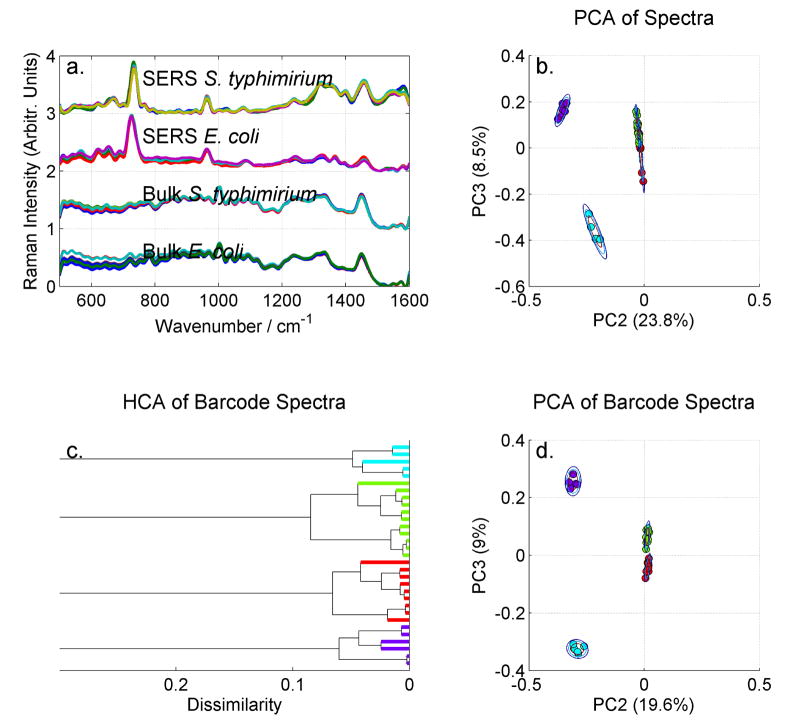

Having established the specificity afforded by the barcode reduction of SERS spectra for multivariate data analysis, we will use this approach to highlight an essential attribute of SERS for microorganisms identification. Aside from the advantages resulting from the Raman cross section enhancement, such as reduced data collection time, single cell level sensitivity and reduced incident laser power requirements (thus enabling portable and remote (SERS) Raman detection instrumentation) a somewhat more subtle but important attribute for bacterial identification derives essentially from the distance and orientation dependence of the SERS enhancement mechanisms. We previously noted that SERS spectra of E. coli and S. typhimurium were more spectrally distinct that their corresponding nonSERS (bulk) Raman spectra based on qualitative spectral comparison and first derivative difference spectra.11,13 Non-SERS or bulk Raman spectra of bacterial species often exhibit only very subtle spectral differences even for bacteria from different genera although these distinction can be discerned in PCA analysis.

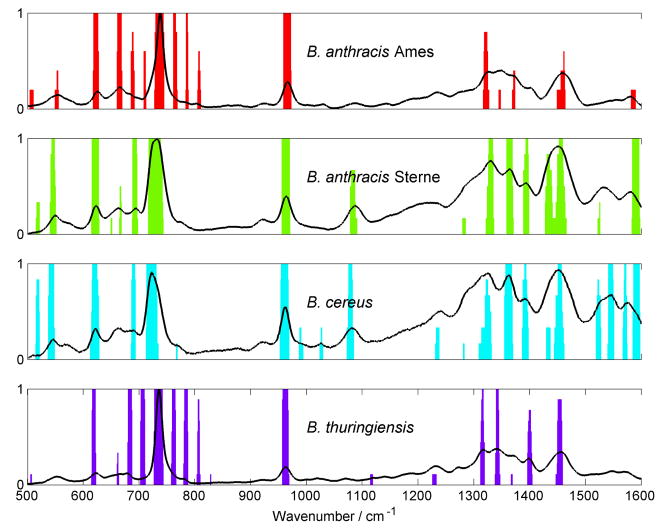

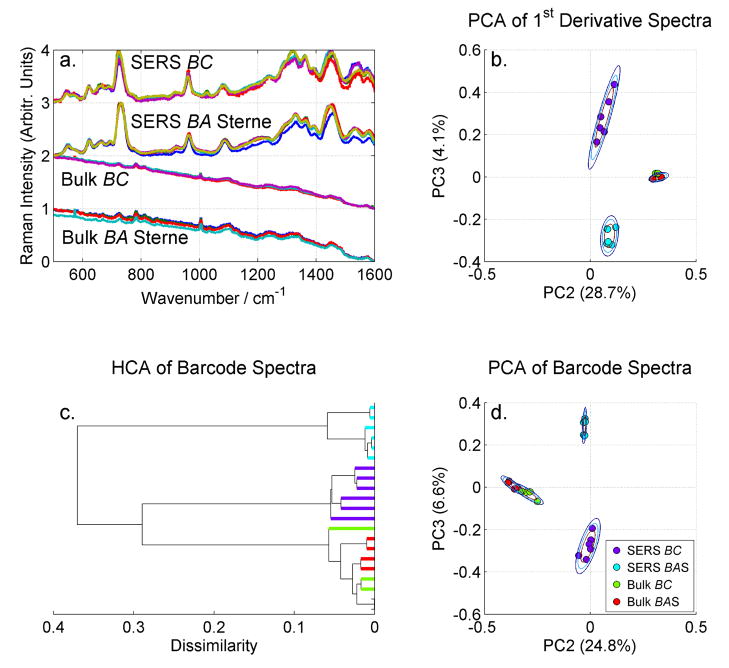

The results of a PCA treatment of SERS and bulk Raman signatures are displayed in Figs. 8 and 9 which dramatically illustrate the enhanced bacterial specificity afforded by SERS vibrational signatures as compared to bulk Raman data. A PC clustering analysis was carried out for bulk (nonSERS) and SERS spectra of S. typhimurium and E. coli displayed in Fig. 8a. The corresponding first derivative spectra were used as input vectors to the clustering algorithm resulting in the PC2 vs. PC3 plot displayed in Fig. 8b. When the first derivative spectra are used the SERS spectra form separate clusters while the non-SERS spectra significantly overlap. When the PCA of the second derivative barcodes is carried out for these two species, well-separated clusters of S. typhimurium and E. coli SERS spectra are obtained again but only slightly separated clusters corresponding to the non-SERS (bulk) Raman signatures are evident (Fig. 8d). This same result is represented in the HCA dendrogram (Fig. 8c) resulting from this barcode PCA treatment. The branch point indicating discrimination between the two groups of SERS spectra occurs at a much larger dissimilarity score (~.35) than that of the corresponding bulk spectra (~.025). The use of this multivariate data analysis approach highlights how much more distinct the SERS spectral signatures are compared to the normal bulk Raman spectra.

Figure 8.

a. SERS and non-SERS bulk spectra of S. typhimurium (ST) and E. coli (EC). b. PCA plot of the corresponding first derivative SERS and non-SERS spectra. c. HCA dendrogram of SERS and non-SERS PCA clusters resulting from the barcode treatment of the spectra shown in a. d. PCA barcode clustering of SERS and bulk ST and EC spectra.

Figure 9.

a. SERS and non-SERS bulk spectra of B. cereum (BC) and B. anthracis Sterne (BA Sterne). b. PCA plot of the corresponding first derivative SERS and non-SERS spectra. c. HCA dendrogram of SERS and non-SERS PCA clusters resulting from the barcode treatment of the spectra shown in a. d. PCA barcode clustering of SERS and bulk ST and EC spectra.

The analogous results are shown in Fig. 9 for SERS and non-SERS spectra of B. cereus and B. anthracis Sterne. As discussed previously11 a broad fluorescent background is observed in the 785 nm excited emission of the bulk bacillus bacteria (Fig. 9a). The PCA plots clearly show how the SERS spectra of these two closely related species form widely separated clusters and properly identified groupings in the HCA barcode-based dendrogram. In contrast, the non-SERS spectra of B. cereus and B. anthracis Sterne are not well separated and are incorrectly grouped in the HCA dendrogram resulting from the barcode PCA treatment. An additional contributing factor for the greater difficulty in HCA classification may be the lower signal to noise of the nonSERS spectra as compared to the SERS spectra due to the large fluorescence background exclusively observed in the bulk Raman emission.

These results illustrate an important property of the SERS optical approach for bacterial identification in addition to the attributes of sensitivity, speed, ease of use and portability. Due to the distance dependence of the SERS enhancement mechanisms, only the outer layer of bacterial cells contributes to these SERS spectra. Non-SERS Raman (and IR) vibrational spectra of bacteria have spectral intensities generated by all cellular components; the cytoplasm, where most of the biomass resides, as well as the outer wall layers. Due to the relative number density of these components the cytoplasm contributions will significantly overwhelm the outer layer components in these non-SERS spectra. That the outer layers of bacteria are more chemically distinct than their corresponding cytoplasm components and hence bacterial SERS spectra more species/strain specific than non-SERS, appears consistent with the view that closely related species, such as the cereus group of Bacillus bacteria, have successfully evolved to occupy different environmental niches while maintaining nearly the same cytoplasmic composition. Thus, they are most distinct where they interact with the outside world and SERS spectral analysis fortuitously, is based on these distinctions, which enhances its diagnostic specificity.

Conclusion

In order to fully exploit the sensitivity and selectivity that SERS offers for bacterial identification rapid, robust spectral analysis protocols employing reference library information must be optimized. Multivariate procedures are required to achieve accurate diagnosis and maximized selectivity based on these vibrational fingerprints. PCA algorithms based on the sign of the second derivative of bacterial SERS spectra observed on the Au nanoparticle covered SiO2 substrates developed in this laboratory11 are shown to result in clusters that show high selectivity and improved reproducibility as compared to spectral intensity, first or second derivative based inputs. Both excellent species and strain specificity is obtained with these SERS spectral based barcodes in PCA, HCA or DFA clustering approaches. Furthermore, clustering analysis allows the observed SERS bacterial reproducibility and specificity achievable due to the sol-gel in situ grown gold nanoparticle substrate and the data reduction methodology to be compared with prior SERS studies as judged by the intragroup and intergroup distances respectively. The second derivative based barcode analysis shown here provides enhanced specificity and reproducibility compared to previously reported SERS bacterial multivariate analyses9,10,14,19 as judged by these distance criteria.

The success of the second derivative barcodes argues firstly that relative intensities and slowly varying background corrections contribute non-essential variances to the data analysis of these SERS spectra. The consistent trend we observe, as the examples shown here demonstrate, is that clustering improves as the input vectors to the bacterial PCA analysis progress from SERS spectral intensities, to first derivative spectra, second derivative spectra and finally to simply upward (0/1) or downward (1/0) curvature as a function of scattered frequency. The sign of the second derivative spectrum, i.e. the location of peaks and valleys, is found to be an extremely robust identification feature, subject to minimal variability, for the SERS spectra of bacteria acquired on the sol-gel substrate used here. First derivative spectra avoid contributions resulting from fluctuations in spectral background, but are still apparently sensitive to SERS vibrational intensity fluctuations. Second derivative spectra similarly minimizes background variability and tend to further reduce sensitivity to intensity fluctuations as shown here. Further bacterial SERS spectral reduction to the binary second derivative representation (barcodes) eliminates even further signal fluctuations due all the sources of intensity variations contributing to these spectra.

Developing SERS for rapid and reagentless bacterial identification by use of a reference library of bacterial spectral data is inherently a supervised multivariate analysis technique since it uses a priori knowledge and thus, an inherently supervised approach such as DFA would seem most appropriate for this classification procedure. However, the standard DFA algorithms used to enhance the ratio of between group to intragroup variance may inadvertently enhance false positive rates, as demonstrated here. In other words, the rotation of PCs that results in improved classification of identified groups in DFA treatments does not necessarily result in DF coordinates that maximize the variance for nongroup member PCs. Unsupervised clustering algorithms, which just characterize the variance in a given training set, are less sensitive to such false positive classifications. Thus, the results demonstrated here indicate the potential for false positive bacterial diagnosis due to such simple supervised multivariate protocols.

The PCA analysis of the bacterial SERS and non-SERS vibrational fingerprints of a given species results in clusters which demonstrate the enhanced specificity as well as sensitivity obtained from the SERS approach. The outer layers of bacteria, which contribute the dominant character of SERS signatures owing to the distance dependence of the SERS enhancement mechanisms, are evidently more chemically distinct than the cytoplasm. Characteristics such as drug resistance, some of which depends on the presence of particular surface features, thus should be amenable to SERS identification even for very closely related strains.

The molecular origin of the bacterial SES fingerprints observed here is still a largely unresolved. For example, the generally most intense vibrational band which is seen at about 730 cm−1 is one of the most ubiquitous features of bacterial SERS spectra. However, it’s molecular origin has variously been assigned to adenosine ring stretch,7,19 or glucosidic ring in NAG/NAM, components of the cell surface polysaccharide layer.9,14 Recently, we observed a large (~10 cm−1) downsshift when Bacillus anthracis is fed nitrogen-15 labeled culture broth consistent with the assignment of a C-N stretching feature to this band.34 Thus, even the assignment of this most intense feature has not been fully established yet. Establishing the molecular origins of these bands arising from cell surface components will be useful for exploiting SERS as a probe of cell surface structures in general and the differences between closely related strains with corresponding different virulence factors in particular.

Acknowledgments

The support of the Army Research Laboratory (Cooperative Agreement DAAD19-00-2-0005) and the National Institute of Health (Grant # AI066641) are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Vo-Dinh T, Yan F, Stokes DL. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;300:255–83. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-858-7:255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yonzon CR, Haynes CL, Zhang X, Walsh JT, Jr, Van Duyne RP. Anal Chem. 2004;76:78–85. doi: 10.1021/ac035134k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanmukh S, Jones L, Zhao YP, Driskell JD, Tripp RA, Dluhy RA. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-1851-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pal A, Isola NR, Alarie JP, Stokes DL, Vo-Dinh T. Faraday Discuss. 2006;132:293–301. doi: 10.1039/b506341h. discussion 309–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Efrima S, Bronk BV, Czege J. Proceed SPIE. 1999;3602:164–171. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeiri L, Bronk BV, Shabtai Y, Czege J, Efrima S. Colloid Surf A. 2002;208:357. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guzelian AA, Sylvia JM, Janni J, Clauson SL, Spenser KM. Proceed SPIE. 2002;4577:182–192. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fell NF, Jr, Smith AGB, Vellone M, Fountain AW., III Proceed SPIE. 2002;4577:174–181. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarvis RM, Goodacre R. Anal Chem. 2004;76:40–7. doi: 10.1021/ac034689c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarvis RM, Brooker A, Goodacre R. Anal Chem. 2004;76:5198–202. doi: 10.1021/ac049663f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Premasiri WR, Moir DT, Klempner MS, Krieger N, Jones G, II, Ziegler LD. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:312–320. doi: 10.1021/jp040442n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Premasiri WR, Moir DT, Ziegler LD. Proceed SPIE. 2005;5795:19–29. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Premasiri WR, Moir DT, Klempner MS, Ziegler LD. Surface enhanced Raman scattering of microorganisms. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarvis RM, Brooker A, Goodacre R. Faraday Discuss. 2006;132:281–92. doi: 10.1039/b506413a. discussion 309–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahraman M, Yazici MM, Sahin F, Bayrak OF, Culha M. Appl Spectrosc. 2007;61:479–85. doi: 10.1366/000370207780807731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahraman M, Yazici MM, Sahin F, Culha M. Langmuir. 2008 doi: 10.1021/la702240q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laucks ML, Sengupta A, Junge K, Davis EJ, Swanson BD. Appl Spectrosc. 2005;59:1222–8. doi: 10.1366/000370205774430891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sengupta A, Laucks ML, Davis EJ. Appl Spectrosc. 2005;59:1016–23. doi: 10.1366/0003702054615124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guicheteau J, Christesen SD. SPIE. 2006;6218:62180G-1–62180G-8 . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naumann D, Helm D, Labischinski H. Nature. 1991;351:81–2. doi: 10.1038/351081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naumann D, Keller S, Helm D, Schultz C, Schrader B. J Mol Struct. 1995;347:399–406. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirschner C, Maquelin K, Pina P, Ngo Thi NA, Choo-Smith LP, Sockalingum GD, Sandt C, Ami D, Orsini F, Doglia SM, Allouch P, Mainfait M, Puppels GJ, Naumann D. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1763–70. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.5.1763-1770.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maquelin K, Kirschner C, Choo-Smith LP, van den Braak N, Endtz HP, Naumann D, Puppels GJ. J Microbiol Methods. 2002;51:255–71. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(02)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maquelin K, Choo-Smith LP, Endtz HP, Bruining HA, Puppels GJ. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:594–600. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.2.594-600.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maquelin K, Kirschner C, Choo-Smith LP, Ngo-Thi NA, van Vreeswijk T, Stammler M, Endtz HP, Bruining HA, Naumann D, Puppels GJ. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:324–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.324-329.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutsebaut D, Maquelin K, De Vos P, Vandenabeele P, Moens L, Puppels GJ. Anal Chem. 2004;76:6274–81. doi: 10.1021/ac049228l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang WE, Griffiths RI, Thompson IP, Bailey MJ, Whiteley AS. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4452–8. doi: 10.1021/ac049753k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maquelin K, Choo-Smith LP, van Vreeswijk T, Endtz HP, Smith B, Bennett R, Bruining HA, Puppels GJ. Anal Chem. 2000;72:12–9. doi: 10.1021/ac991011h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarvis RM, Goodacre R. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:860–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Udelhoven T, Naumann D, Schmitt J. Appl Spectrosc. 2000;54:1471–1479. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Helgason E, Okstad OA, Caugant DA, Johansen HA, Fouet A, Mock M, Hegna I, Kolsto Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2627–30. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.6.2627-2630.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alsberg BK, Kell DB, Goodacre R. Anal Chem. 1998;70:4126–4133. doi: 10.1021/ac980506o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mock M, Fouet A. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:647–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Premasiri WR, Moir DT, Ziegler LD. J Phys Chem B. (in preparation) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pomerantsev AP, Kalnin KV, Osorio M, Leppla SH. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6591–606. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6591-6606.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green BD, Battisti L, Koehler TM, Thorne CB, Ivins BE. Infect Immun. 1985;49:291–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.291-297.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLean RJ, Beauchemin D, Clapham L, Beveridge TJ. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3671–3677. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.12.3671-3677.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]