Abstract

Objectives

Based on a life-course risk-chain framework, we examined whether (1) residual associations between childhood SES and adult obesity and BMI would be observed in women, but not men after adjusting for adult SES; (2) adult Big Five personality traits would be associated with adult body mass in both genders, and (3) personality would explain unique variation in outcomes beyond child and adult SES.

Design

National survey (Midlife Development in the US study; N = 2922).

Main Outcome Measures

BMI and obesity.

Results

(1) in both genders, association between childhood SES and adult obesity were accounted for entirely by adult SES, but its effect on adult BMI was observed only in women. (2) Higher Conscientiousness was associated with lower obesity prevalence and BMI in both genders, though more strongly in women. In men, greater obesity prevalence was associated with higher Agreeableness and Neuroticism. (3) Personality explained unique outcome variation in both genders.

Conclusions

Early social disadvantage may affect adult weight status more strongly in women owing to gender differences in the timing and nature of weight-management socialization. Personality may enhance or detract from risks incurred by childhood or adulthood SES in either gender, necessitating the consideration of dispositional differences in prevention and intervention programs.

Keywords: Obesity, BMI, socioeconomic status, personality, gender differences, Midlife Development in the US

Obesity is a major public health problem in industrialized societies (Cope & Allison, 2006; McLaren, 2007), resulting in levels of morbidity nearly comparable to smoking and poverty (Sturm & Wells, 2001). Although the direction and strength of social gradients in obesity may vary depending a country's level of industrialization and age cohort, in many countries, social inequalities in body mass appear relatively early in life (McLaren, 2007; van der Horst et al., 2007) and endure through adulthood. Importantly, individuals born into higher childhood socioeconomic status (SES) show lower rates of adult obesity (Sarlio-Lahteenkorva, 2007). A major question, however, is whether associations between lower childhood SES and adult obesity can be explained by adult SES (Drewnowski & Specter, 2004; Klohe-Lehman et al., 2006). If the effects of childhood SES on adult weight status are mediated entirely through adult SES, then prevention and intervention resources altering the path from childhood social disadvantage to adult social disadvantage may have a substantial impact on reducing weight-related morbidity in adulthood. If, on the other hand, childhood SES effects on adult weight status can be only partially explained by adult SES, then other paths from social early social disadvantage to adult weight problems exist, requiring additional consideration in prevention and intervention efforts.

Some reports indicate that adult SES completely mediates associations between childhood SES and adult obesity (Lawlor et al., 2005; Regidor, Gutierrez-Fisac, Banegas, Lopez-Garcia, & Rodriguez-Artalejo, 2004), while others indicate substantial residual effects for childhood SES after adult SES has been controlled (Laaksonen, Sarlio-Lahteenkorva, & Lahelma, 2004; Langenberg, Hardy, Kuh, Brunner, & Wadsworth, 2003). However, associations between obesity and both adult SES (Zhang & Wang, 2004) and childhood SES appear stronger in women (Case & Menendez, 2007; Laaksonen et al., 2004). This raises the possibility that potential residual childhood SES risk for unhealthy adult weight is gender-specific.

However, weight status in adulthood is a function not only of social gradients in the distribution of wealth and resources, but also of individual differences in behavioral tendencies and psychological factors (Cope & Allison, 2006; Glass & McAtee, 2006). A second question therefore is whether the associations of childhood social class and adult weight status can also be explained to some extent by individual personality characteristics in adulthood. The “Big Five” phenotypic personality traits of Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness comprise the major axes of dispositional behavioral variation in humans (Goldberg, 1993), and constitute “intermediate phenotypes” reflecting a joint expression of both genetic and social environmental factors influencing health (Institute of Medicine, 2006). Three traits have been implicated directly in weight gain in adulthood (Brummett et al., 2006): lower Extraversion (or low levels of positive mood, energy, and sociability) in men, higher Neuroticism (or high levels of or stress reactivity and general negative mood) in women, and lower Conscientiousness (or low levels of or reliability, achievement striving, and self-discipline) in both genders.

How do personality and socioeconomic forces work in conjunction to influence adult weight status? Life course epidemiology (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002; Kuh, Ben-Shlomo, Lynch, Hallqvist, & Power, 2003) provides at least three conceptual models. First, a risk chain model with triggering effects suggests that lower childhood SES influences adult weight status entirely through lower adult SES, and/or personality traits. In other words, the initial risk of early social disadvantage triggers later risks, such as lower adult SES and low Conscientiousness, that are proximally tied to obesity. Some studies provide support for such a model, documenting complete mediation of childhood SES by adult SES (Lawlor et al., 2005; Regidor et al., 2004). However, when substantial residual associations between childhood SES adult obesity are observed after adjusting for adult SES (Laaksonen et al., 2004; Langenberg et al., 2003), the risks of childhood SES work through additional pathways, suggesting a second risk chain model of partial mediation.

A third risk accumulation model with independent additive effects suggests that the association of early exposures, such as childhood social disadvantage, with adult obesity is essentially unmediated by adult personality. The latter may independently add to (exacerbate) and/or subtract from (compensate for) the risk conferred by childhood and adult SES. If such a model prevails, the risk conferred by disadvantaged childhood SES may be offset by protective traits in adulthood such as high Conscientiousness, or the benefit of childhood advantage may be erased by personality traits linked to obesity and higher BMI. In this case, adult personality traits would be useful for explaining heterogeneity in weight status among individuals of similar childhood or adult SES, constituting an important “individual” level adjunct to societal factors, such as socioeconomic gradients, which influence weight status (Cope & Allison, 2006).

Virtually no studies have reported on the extent to which childhood social disadvantage affects standing on adult personality traits. However, a model of independent additivity for personality and SES would appear consistent with a recent report that adult temperament and childhood SES exerted largely independent effects on adult waist-circumference (Sovio, King, Miettunen, Ek, Laitinen, Joukamaa, et al., 2007). Other findings have documented independent associations between adult BMI and childhood temperament, independent of childhood SES (Pulkki-Råback, Elovainio, Kivimäki, Raitakari, & Keltikangas-Järvinen, 2005) and BMI and childhood Big Five traits, independent of education (Hampson, Goldberg, Vogt, & Dubanoski, 2006). To the extent that childhood personality is associated with adult personality, these studies provide further clues about the possible independent additivity of adult personality.

We examined the joint influences of childhood SES, adult SES, and adult personality traits on obesity and BMI in a United States cohort with rich data on both the Big Five and SES in childhood and adulthood. Based on previous findings (Laaksonen et al., 2004; Zhang & Wang, 2004), we hypothesized that residual effects of childhood SES on adult weight status would be observed for women, but not men. This corresponds to different life course epidemiologic risk chain models in which childhood SES effects are partially mediated by adult SES in women, but completely mediated or triggered by adult SES in men.

We further hypothesized that adult personality would be associated with weight status independently of SES, explaining additional variation in BMI and obesity (Sovio et al., 2007). Specifically, we expected low Extraversion in men, high Neuroticism in women, and low Conscientiousness in both genders to be associated with higher adult body mass (Brummett et al., 2006). From the perspective of life-span epidemiologic models, we thus expected independent additive risks for adult personality vis-à-vis SES in both genders, though we suspected that the particular traits associated with weight status would differ in men and women.

METHOD

Study Population

The Midlife Development in the US (MIDUS) study was a national survey conducted in 1995 by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation which has been described extensively elsewhere (Brim, O.G., Ryff, C.D., & Kessler, R.C., 2004). Approved by ethical oversight boards, the study recruited non-institutionalized, English-speaking adults aged 25-74 years (younger [25-39] and older [61-75] individuals included for comparison purposes to midlife persons [40-60; Brim et al., 2004]) using random-digit dialing, and examined numerous social, behavioral, and psychological factors associated with health through a phone interview and mailed questionnaire. The overall response rate for the telephone portion of the study was 70%, and another 86.8% of these persons completed the mail-in survey (Brim et al., 2004). Of the 4242 individuals completing at least the phone interview, 2992 (71%) had complete data on all variables of interest in the present analyses, which came from both the telephone and survey portions. The greatest percentage of missing single variables were observed for survey questions on personality traits (14%) and employment (28%) or household income (16%). Multivariate logistic regression examining demographic differences between those with and without complete data on variables of interest revealed that the current analysis sample did not differ from the larger sample in terms of race or gender, but the analysis sample was about half a year older (i.e., 46.5 vs. 46, z = 2.58, p = .01) and had a higher proportion of more educated persons (i.e., 8.4% had less than high-school education, 26.7% had high school, 30.6% had some college, and 34.3% had college or greater, compared with 18.4%, 27.2%, 29.8%, and 24.5%, respectively, among those with incomplete data; X2 = 109.48, df = 3, p < .001).

Study Measures

Body mass index (BMI) was assessed via survey questions asking respondents to report their height and weight. Obesity was classified as BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above. Some studies have reported high correlations between self-reported and measured weight (Lowe, Miller-Kovach, & Phelan, 2001), while others suggest that self-reported height and weight may underestimate actual BMI (Taylor, Dal Grande, Gill, Chittleborough, Wilson, Adams, Grant, Phillips, Appleton, Ruffin, 2006).

Childhood SES was measured using Duncan's Socioeconomic Index (SEI) of respondents' parents' occupational prestige (highest of mother and father), for respondent's report of their parents' occupation when the respondent was 12-18 years old (Stevens & Cho, 1985). Focusing on the 12-18 year time period captures parental promotions or occupational advances, occurring after early childhood, during the formative adolescent years. Parental SEI was standardized to a mean of 0 and SD of 1 according to the MIDUS sample in order to facilitate interpretation. Thus, a one unit increase reflects a 14.46 SEI increase, roughly the difference between a milling machine operator (SEI 21.86) and a construction inspector (SEI 36.38). Standardized scores of -1 (i.e., taxi cab driver, SEI 22.46), 0 (i.e., rail road yard master, SEI 36.47), and 1 (i.e. air traffic controller, SEI 50.11) also provide a rough index of low, average, and high parental occupational status.

Adult SES was assessed by a comprehensive set of indicators, consistent with both indicators implicated in recent reviews on obesity (McLaren, 2007), and the importance of implementing a wide range of SES indices (Galobardes et al., 2006a, b.) These were: 1) education (indicator variables for high school, some college, or college and higher against a reference category of less than high school), 2) annual household income (scaled in $10,000 increments); and 3) respondents' adult SEI (current job, or most recent job for those unemployed or retired, standardized to mean of 0 and SD of 1); and 4) an indicator for non-retirement related unemployment (vs. employed). As both marriage and retirement are factors significantly tied to adult social and economic resources, we also included 5) an indicator for married (vs. single, divorced, widowed) and 6) an indicator for retired (vs. not retired). Other adult demographic covariates included age, an indicator variables for female (vs. male), and African American and other race/ethnicity (against Caucasian reference category).

Big Five phenotypic personality traits were assessed via the Midlife Development Inventory Big Five scales (Lachman & Weaver, 1997), which asked respondents how well each of four to seven trait markers for each of the Big Five (Goldberg, 1992) described them, using a four point Likert scale from “A lot” to “Not at all.” Cronbach's alpha estimates of internal consistency reliability for each scale were: Neuroticism, .74; Extraversion, .78; Openness to Experience, .77; Agreeableness, .80; and Conscientiousness, .58. Scores were standardized to a mean of 0 and an SD of 1 based on the complete MIDUS sample to facilitate interpretation.

Statistical Analysis

Because our hypotheses were driven by prior findings of strong gender differences in the associations of SES and personality with weight status, all analyses were stratified a priori by gender. This could be done with preservation of relatively equal power, because the sampling scheme of MIDUS assured relatively equal numbers of men and women. However, because stratified analyses reveal only whether effects are significant or not in each gender, analyses also tested for differences in the magnitude of significant effects across gender with interaction terms.

Preliminary analyses examined the associations of childhood SES with 1) adult SES and 2) personality factors. The reason was that if adult SES was not associated with childhood SES, the former could not mediate the effect of the latter. If one or both types of SES factors were too strongly linked to personality, the possibility of independent additivity for personality traits would be diminished. We examined these relationships using seemingly unrelated regression (SUR; Greene, 2003), which estimates associations between a set of predictors and several dependent variables (DVs) simultaneously, accounting for correlated error terms among the outcomes that may arise from unobserved factors which affect all the outcomes, such as response sets operating across personality scales, or macro-economic conditions influencing a number of measures of SES. Childhood SES effects on unemployment, marital status, and retirement were modeled in separate logistic regressions.

Primary analyses consisted of a series of nested generalized linear models. As obesity rates (21%) exceeded the rare-disease threshold (10%) for which logistic regression odds ratios accurately approximate relative risk (RR), we estimated obesity RRs (which are prevalence ratios [PRs] in cross-sectional studies) using a modified Poisson approach with sandwich-estimated standard errors. This form of relative risk regression provides more accurate RR estimates and confidence intervals than post-hoc transformation of odds ratios (Greenland, 2004; McNutt, Wu, Xue, & Hafner, 2003; Zou, 2004). BMI was modeled with robust linear regression.

The nested models consisted of a base model (Model 1) containing parental SEI and covariates gender, age, and race/ethnicity. The next model assessed whether parental SEI effects were mediated by adult SES by adding respondent education, household income, and adult SEI, as well as adult marital status, unemployment, and retirement. Finally, model 3 added the Big Five. Changes in PR or regression coefficient for childhood SES were examined at each step to determine if adult SES factors diminished associations of parental SEI, or if personality factors diminished associations of childhood or adult SES factors models 1 or 2.

We examined linearity assumptions for continuous personality and SES terms in all models using quadratic and cubic terms. To investigate whether the slightly greater measurement error in for the Conscientiousness scale biased results toward the null as would be expected, we fit regression calibration measurement error models (Carroll, Ruppert, & Stefanski, 1995). To evaluate whether the addition of adult SES and personality factors improved multivariate model fit for obesity, we examined changes in pseudo R2 values in prevalence ratio models (significance determined with likelihood ratio tests) and changes in adjusted R2 values in linear regressions (significance determined with generalized F tests). Finally, as reviews (Zhang & Wang, 2004) have suggested different gender-specific associations of SES indicators and obesity in persons of black race/ethnicity, secondary analyses refit models in Caucasians only, as low minority participation rate precluded stratified analysis. Analyses were conducted in Stata 10 Special Edition (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the sample as a whole and stratified by BMI categories. SUR models revealed that parental SEI was associated with a number of adult SES indicators (accounting for 4-17% of their variance), and minimally associated with adult personality traits of interest (accounting for 1-5% of their variance). Thus, adult SES factors met criteria for potential mediation, and adult personality traits for potential additive independence.

Table 1.

Sample Descriptives by Weight Category

| Non-Obese (n = 2367) | Obese (n = 625) | Overall (N = 2922) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or % | |

| BMI | 24.6 (3.1) | 34.8 (4.6) | 26.7 (5.4) |

|

| |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age (Years) | 46.0 (13.4) | 48.2 (11.9) | 46.5 (13.1) |

| Black | 5% | 10% | 6% |

| Other Race | 5% | 4% | 5% |

| Female | 48% | 52% | 49% |

|

| |||

| Socioeconomic Factors | |||

| Parental SEI | 39.0 (13.9) | 35.8 (12.9) | 38.3 (13.8) |

| Adult SEI | 40.5 (14.4) | 37.9 (13.8) | 40.0 (14.3) |

| < High School Education | 8% | 11% | 8% |

| High School Education | 25% | 33% | 27% |

| Some College Education | 30% | 31% | 31% |

| College or Greater Education | 37% | 25% | 34% |

| Median Household Income | $52,000 | $47,500 | $51,000 |

| Married | 64% | 66% | 65% |

| Retired | 10% | 8% | 10% |

| Unemployed | 11% | 14% | 12% |

Note: Means (SD) or %.

Nested models comprising the primary analyses for obesity are presented in Table 2. A one SD increase in parental SEI amounted to a 14% reduction in obesity risk in each gender, but this effect was explained completely by adult SES factors in both men and women. Marriage was associated with higher obesity prevalence in men only. Retirement and college education were both associated with lower obesity prevalence in men. Personality traits did not appear to appreciably diminish the association of SES factors with obesity in either gender, and greater Neuroticism was associated with lower obesity prevalence in men, but not women. Greater Conscientiousness was associated with lower obesity prevalence in both genders.

Table 2.

Association Between Adult Obesity and Childhood and Adult SES and Personality

| Men (n = 1537) | Women (n =1455) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Age | 1.01 [1.00,1.01] | 1.01** [1.01,1.02] | 1.01** [1.01,1.02] | 1.01** [1.00,1.02] | 1.01** [1.00,1.02] | 1.01** [1.00,1.02] |

| Black | 1.36 [0.91,2.04] | 1.32 [0.89,1.95] | 1.27 [0.87,1.86] | 1.95*** [1.50,2.53] | 1.88*** [1.43,2.48] | 1.82*** [1.38,2.42] |

| Other Race | 1.11 [0.72,1.72] | 1.19 [0.77,1.83] | 1.17 [0.76,1.79] | 0.86 [0.50,1.50] | 0.88 [0.51,1.52] | 0.86 [0.50,1.47] |

| Parental SEI | 0.86* [0.77,0.97] | 0.94 [0.83,1.07] | 0.94 [0.83,1.06] | 0.86** [0.78,0.96] | 0.91 [0.81,1.02] | 0.92 [0.82,1.03] |

|

| ||||||

| Adult SEI | 1.04 [0.92,1.19] | 1.03 [0.90,1.17] | 0.96 [0.85,1.10] | 0.97 [0.86,1.10] | ||

| Unemployed | 0.85 [0.57,1.26] | 0.81 [0.56,1.19] | 1.09 [0.85,1.39] | 1.05 [0.82,1.34] | ||

| Retired | 0.45*** [0.28,0.72] | 0.46** [0.29,0.74] | 0.74 [0.51,1.07] | 0.71 [0.50,1.02] | ||

| High School Education | 1.14 [0.80,1.62] | 1.15 [0.81,1.63] | 0.95 [0.68,1.32] | 1.06 [0.75,1.49] | ||

| Some College Education | 0.97 [0.67,1.41] | 0.97 [0.66,1.41] | 0.88 [0.62,1.25] | 0.99 [0.70,1.42] | ||

| College or Greater Education | 0.63* [0.41,0.96] | 0.63* [0.41,0.96] | 0.78 [0.50,1.24] | 0.95 [0.59,1.52] | ||

| Married | 1.48** [1.14,1.93] | 1.51** [1.16,1.98] | 0.94 [0.76,1.17] | 0.95 [0.76,1.17] | ||

| 10Ks of Household Income | 1.00 [0.98,1.02] | 1.00 [0.98,1.02] | 0.99 [0.96,1.01] | 0.99 [0.97,1.01] | ||

|

| ||||||

| Neuroticism | 0.88* [0.79,0.98] | 0.98 [0.89,1.09] | ||||

| Extraversion | 0.89 [0.78,1.02] | 0.95 [0.84,1.08] | ||||

| Openness | 1.09 [0.95,1.25] | 0.93 [0.83,1.04] | ||||

| Agreeableness | 1.20** [1.06,1.37] | 1.14 [0.98,1.32] | ||||

| Conscientiousness | 0.81*** [0.73,0.90] | 0.80*** [0.72,0.89] | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Pseudo R2 | .0307 | .0516 | .0638 | .0583 | .0630 | .0737 |

Notes: Prevalence Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals).

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

Personality and SEI scores standardized (Mean = 0 SD = 1). Model 1 = demographic factors and childhood SES only; Model 2 = Model 1 + adult SES; Model 3 = Model 2 + adult personality.

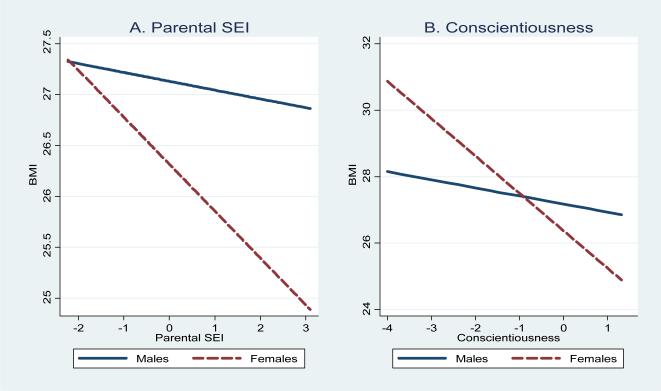

Linear regressions revealed persisting residual effects of parental SEI on BMI in women, but not men (Table 3). The left panel of Figure 1 shows the regression slopes for residual effects of parental SEI in each gender after full adjustment for adult SES and personality. In women, greater household income was also associated with lower BMI. Marriage was significantly associated with higher BMI in men, but not women. Higher Agreeableness was associated with higher BMI in men, but not women. Finally, greater Conscientiousness was associated with lower BMI in both genders, but the effect was much more pronounced in women (p < .001). The right panel of Figure 1 depicts gender differences in adjusted regression slopes.

Table 3.

Association between Adult BMI and Childhood and Adult SES and Personality

| Men (n = 1537) | Women (n =1455) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Age† | 0.03** (0.01) | 0.04*** (0.01) | 0.04*** (0.01) | 0.06*** (0.01) | 0.06*** (0.01) | 0.07*** (0.01) |

| Black | 0.59 (0.63) | 0.48 (0.62) | 0.47 (0.61) | 3.79*** (0.77) | 3.74*** (0.78) | 3.54*** (0.79) |

| Other Race | 0.29 (0.65) | 0.46 (0.65) | 0.42 (0.65) | -0.33 (0.64) | -0.23 (0.64) | -0.30 (0.63) |

| Parental SEI | -0.38** (0.12) | -0.19 (0.13) | -0.17 (0.12) | -0.58*** (0.15) | -0.34* (0.17) | -0.34* (0.17) |

|

| ||||||

| Adult SEI | -0.13 (0.13) | -0.11 (0.13) | -0.21 (0.21) | -0.19 (0.20) | ||

| Unemployed | -0.58 (0.44) | -0.69 (0.44) | 0.64 (0.48) | 0.48 (0.48) | ||

| Retired | -1.46*** (0.41) | -1.45*** (0.41) | -0.94 (0.62) | -1.11 (0.59) | ||

| High School Education | 0.54 (0.45) | 0.63 (0.45) | 0.39 (0.62) | 0.83 (0.62) | ||

| Some College Education | 0.34 (0.47) | 0.49 (0.47) | 0.25 (0.63) | 0.73 (0.64) | ||

| College or Greater Education | -0.46 (0.48) | -0.26 (0.49) | -0.42 (0.72) | 0.20 (0.74) | ||

| Married | 0.92*** (0.26) | 0.89*** (0.26) | 0.38 (0.36) | 0.40 (0.35) | ||

| 10Ks of Household Income | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) | -0.08** (0.03) | -0.07* (0.03) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Neuroticism | -0.15 (0.12) | -0.15 (0.16) | ||||

| Extraversion | -0.06 (0.15) | -0.21 (0.21) | ||||

| Openness | -0.24 (0.15) | -0.08 (0.19) | ||||

| Agreeableness | 0.44*** (0.12) | 0.23 (0.25) | ||||

| Conscientiousness† | -0.32 (0.12) | -1.05*** (0.21) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Adjusted R2 | .0138 | .0373 | .0460 | .0521 | .0628 | .0855 |

Note: Linear regression coefficients (standard errors).

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Coefficient differs by gender, p < .05.

Personality and SEI scores standardized (Mean=0 SD=1). Model 1 = demographic factors and childhood SES only; Model 2 = Model 1 + adult SES; Model 3 = Model 2 + adult personality.

Figure 1.

Fully Adjusted Relationship of Parental SEI and Conscientiousness to BMI in Men and Women

Finally, of demographic covariates, Black race/ethnicity was significantly associated with obesity prevalence and higher BMI in women only, while greater age was associated with higher BMI in both genders, but showed a stronger effect in women (p = .027). A quadratic effect for income was also observed in men, such that higher income was associated with higher BMI up to roughly $100,000, but with lower BMI beyond $100,000. However, this effect appeared due to a relatively small proportion of men with incomes over $200,000, so it was not included in final models. No other non-linearities were apparent, and secondary analyses using only Caucasian respondents revealed nearly identical findings. Regression calibration analyses revealed that measurement error in the Conscientiousness scale biased the observed effect toward the null.

Adjusted and pseudo-R2 values suggested that the addition of adult SES indicators improved explanatory power for both obesity in men (Δ pseudo-R2 = .0209, X2 (8) = 33.65, p < .001) but not women, and improved explanatory power for BMI in both genders (Δ Adj R2 = .0235, F (8, 1524) = 5.68, p < .001 for men, Δ Adj R2 = .0107, F (8, 1442) = 3.07, p = .002 in women). Personality improved explanatory power in both genders for obesity (Δ pseudo-R2 = .0022, X2 (8) = 19.42, p = .002 for men, Δ pseudo-R2 = .0107, X2 (5) = 18.32, p = .003 for women) and BMI (Δ R2 = .0087, F (5, 1519) = 3.75, p = .002 for men, Δ R2 = .0227, F (5, 1437) = 8.14, p < .001 in women). At each step, models explained more overall variation in obesity and BMI in women (i.e., for final model, pseudo-R2 = .0737 and Adj R2 = .0855), compared to men (pseudo-R2 = .0638 and Adj R2 = .0460). The proportion of explained variance attributable to personality was 19% and 19% for obesity and BMI, respectively, in men, and 15% and 27% for obesity and BMI, respectively, in women.

CONCLUSIONS

After controlling for demographics, SES and personality in adulthood, lower childhood SES exerted no residual effects upon adult obesity in either gender, but remained associated with adult BMI in women. Higher Conscientiousness was associated with lower obesity prevalence and BMI in both genders, though more strongly so for women's BMI. Higher Agreeableness and lower Neuroticism signaled greater obesity prevalence, and higher Agreeableness higher BMI, in men. For each outcome, personality explained additional unique variation. These results extend previous findings on childhood SES gradients in obesity in three ways.

First, some European studies report no association between childhood SES and obesity after accounting for adult socioeconomic indicators (Lawlor et al., 2005; Regidor et al., 2004), while others report substantial residual effects, particularly in women (Laaksonen et al., 2004). Our findings resemble both types of studies, in that childhood SES exerted no residual effect on adult obesity in either gender, but did show persisting associations with BMI in women. This suggests that the social circumstances of one's upbringing confer no residual risk for crossing the threshold of obesity—a relatively high level of BMI—but do exert a long-lasting effect when the entire spectrum of body mass is considered as a continuum in US women.

Consideration of weight status as obese or non-obese represents a useful and convenient designation for clinical and public health purposes, but relinquishes more nuanced information present in dimensional body mass. As a result, associations between various risk factors and the general body mass continuum may be masked, raising two possibilities. First, conflicting findings in prior studies focusing on childhood SES and obesity per se might be interpreted as evidence that some residual association between childhood SES and dimensional adult body mass exists at the population level, but is found only inconsistently when BMI is dichotomized. Second, childhood SES may indeed show residual associations with the BMI spectrum, but not with obesity itself. In other words, childhood SES shows persisting effects across the lower ranges of the BMI gradient, but these effects diminish in the upper ranges of BMI. We may have lacked power to detect subtle non-linearities in specific regions of the BMI continuum.

The apparent tendency for childhood SES to exert residual effects on adult weight status in women, but not men, may be because attention to body shape and size begins at an earlier age in women and may be relatively more intense than for boys (Brownwell, 1991). While adolescent boys' body-cognitions appear to involve concern for muscularity, those of girls are focused on obesity (Wang, Houshyar, & Prinstein, 2006). Greater societal expectations arising at an earlier age may magnify the influence of dietary, exercise, weight-regulatory behaviors, or weight norms arising from childhood SES. In men, elimination of the association between childhood SES and adult obesity as well as BMI by adjustment for adult SES suggests that the timing of SES influences on weight management is later and/or weaker. Another possibility raised by recent investigations of gender differences in the childhood SES—adult weight phenomenon is that the biological changes faced by young women, such as puberty, may be somehow implicated in the persisting effects of childhood disadvantage upon adult weight status (Case & Menendez, 2007). Gender-differential genetic contributions to obesity have also been reported (Allison, Heshka, Neale, Lykken, & Heymsfield, 1994), though sources of potential gender-differential gene-environment interactions remain unknown. Clearly, research is needed to identify the remaining pathways through which childhood SES exerts its effects.

A second important feature of these findings is that different adult SES factors were associated with obesity rates and BMI in men and women. This parallels the conclusion of comprehensive reviews (McLaren, 2007). For men, obesity prevalence was much lower with a college or greater education compared to those with less than high school education. Education associations with obesity and BMI were non-significant in women, in whom higher household income was associated with lower BMI instead. The protective effect of retirement against obesity, and the risk conferred by marital status, were both restricted to men. Thus, “conventional” measure of SES—household income, for women's BMI, and education, for men's obesity prevalence—showed expected associations in both genders, but in men, SES factors tied to life transitions such as marriage and retirement appeared to be additional correlates.

These findings are consistent with observed gender-differential changes in food consumption patterns associated with marriage, such as the transition from cooking relatively infrequently and/or poor-tasting food, as a bachelor, to greater availability and quality of food prepared by one's wife, which may lead to significant weight gain in men two years after marriage (Jeffrey & Rick, 2002). Married men are also more likely to be overweight than nevermarried, divorced, separated, or widowed men (Hanson, Sobal, & Frongillo, 2006). Marital status appears such a powerful determinant of weight status in men that, other than age, it is the strongest predictor of obesity for men in Poland (Lipowicz, Gronkiewicz, & Malina, 2002). Gender differences in typical post-retirement activities may also exist, such as participation by men in hobbies requiring greater energy expenditure like golfing or carpentry.

Third, and perhaps most important, was the finding that personality contributed additively and largely independently to outcome variation in both men and women. In both genders, higher Conscientiousness was associated with lower obesity prevalence and BMI, but the effect for BMI was stronger in women, consistent with prior longitudinal findings (Brummett et al., 2006). Higher Conscientiousness involves greater self-discipline with respect to diet and exercise (Goldberg & Strycker, 2002; Roberts, Walton, & Bogg, 2005), and the effects of self-restraint may be potentiated in women by the culturally-induced focus on body weight. More Agreeable men also appeared to have a higher prevalence of obesity and higher BMI. Agreeableness involves compliance, trust, acquiescence, and interpersonal deference (Goldberg, 1993), and it is possible that such characteristics may raise susceptibility to overeating by reducing adaptive skepticism to marketing campaigns for high-caloric foods, increasing food consumption out of social obligation, or enhancing susceptibility to interpersonal influence and social contagion encouraging overeating (Christakis & Fowler, 2007). More Agreeable men may be more sensitive to interpersonal stressors or threats, which can increase daily snacking (O'Connor, Jones, Conner, McMillan, & Ferguson, 2008). A non-significant prevalence ratio only slightly less in magnitude was observed for higher Agreeableness in women, and secondary analyses indicated that the small difference in magnitude was not statistically significant. Thus, this may have been one case in which the slight difference in sample sizes resulted in less power to detect a similar-sized effect in women, so we caution against premature of dismissal of the possibility that Agreeableness is associated with weight status in women.

A final personality finding of note was that higher Neuroticism was significantly associated with lower, rather than higher obesity prevalence in men, and unassociated with obesity (with the non-significant estimate suggesting higher prevalence) in women. These findings are consistent with the possibility that Neuroticism can reflect adaptive concern over health (Friedman, 2000), at least in men, while the hint of an opposing effect in women was consistent with prior speculation that the trait is linked to maladaptive coping strategies such as overeating and inactivity in females (Brummett et al., 2006). Another intriguing complexity was that Neuroticism was not associated with BMI in either gender. This may mean that in men, the health concern signaled by Neuroticism is less likely to produce weight control behaviors at levels of BMI below the obesity threshold, but becomes sufficiently activated at higher BMI to prevent passage over the obesity threshold. In other words, being only a little overweight may not activate men's health anxiety enough to reveal protective benefits, but when one's weight approaches more obviously and severely unhealthy levels, dispositional worry serves an adaptive function. Such possibilities warrant future consideration.

Overall, findings are consistent with life-course epidemiologic risk-chain models in which the effect of childhood SES on adult weight status is only partially mediated by adult SES in women, and completely mediated by adult SES factors in men. The role of personality in the risk chain would appear to be additive and independent in both genders. Two important conceptual implications exist. First, the residual effects of childhood (dis)advantage in women suggest remaining pathways to adult weight status which require additional investigation. Second, the largely independent effects of SES and personality mean that an adaptive adult personality profile may to some degree offset the risk of lower childhood SES, or a risky personality profile may wash out the protective effects of early life advantage.

At the level of primary prevention early in the life course, our findings support the need for careful consideration of educational and prevention programs in lower SES girls (Kaplan, 2000). Results also suggest attention to individual personality traits across the adult life course in prevention and intervention programs for both sexes. Dispositional psychological factors affect attention and response to preventive health messages (Dutta-Bergman, 2003; Kreuter, & Wrat, 2003), possibly explaining why media-based public health campaigns yield variable results at the level of the individual. An intriguing avenue for future inquiry might be to examine whether public health obesity education campaigns tailored to the personality characteristics associated with obesity in each gender are more effective than those not tailored in this way. However, in the absence of more definitive data, this is best regarded as a topic of translational research rather than an area for current policy implementation.

Interventions may also benefit from tailoring according to patients' trait profiles (Noar, Benac, & Harris, 2007). Individuals lower in Conscientiousness are likely to require extremely gradual change in diet and exercise regimens or treatments that are less dependent on daily adherence, because their tendencies toward disorganization, unreliability, and poor self-discipline may lead to failures in “one size fits all” treatments. Agreeable individuals may need to develop a more skeptical attitude toward the mass-marketing of high-caloric food choices, while also developing social skills that enable them to resist and/or assertively refuse social pressures that may enhance obesity risk. Men low in Neuroticism who are approaching BMIs of 30 may benefit from the induction of health anxiety, to reduce risk of passage into obesity. A final implication for research is the necessity of considering both obesity and BMI in further studies, as each may be sensitive to different factors which ultimately influence body weight.

Findings must be qualified by several limitations. Because the MIDUS survey was cross-sectional, we lacked data on personality and BMI in childhood and could not assess temporal relationships between variables, limiting our ability to ascertain causal sequences. For instance, in the US, low social class continues to be associated with childhood overweight/obesity, and as many as 80 percent of overweight children become obese adults (Wang & Beydoun, 2007). We were unable to examine the role of childhood obesity as a pathway for the enduring effects of childhood SES in women (Wang & Beydoun). The time-frame used to assess parental SEI also may not have captured respondents' childhood SES during earlier periods, or changes in SES over the course of their childhood and adolescence, and the influence of such variability on childhood SES predictive power bears future investigations. Also, although Duncan's SEI captures promotions to higher occupational titles (i.e., construction foreman versus construction worker) that may occur with greater time on a job, it does not capture increasing prestige that may accrue with greater time in a single occupational title, and may not be sensitive to increasing socioeconomic standing from longer job tenure. As well, personality exhibits both stable and changing elements and may be influenced by environmental factors over time (Caspi & Roberts, 2001), so it is difficult to know the extent to which adult personality effects can be accounted for by personality and temperament in childhood (Hampson et al., 2006; Pulkki-Råback et al., 2005), or the extent to which traits are themselves shaped by obesity. For instance, obese men may show elevated Agreeableness as an adaptation to offset the interpersonal stigma attached to their weight. Addressing such important questions will require additional investigations. The Conscientiousness scale contained greater measurement error than other personality scales. However, regression calibration analyses confirmed that this attenuated its associations with weight status, meaning that our reported estimates of the protective role of Conscientiousness are conservative. Additionally, although the MIDUS study tried to recruit as representative a US sample as possible, individuals of higher education and Caucasian race/ethnicity were overrepresented in sampling (Brim et al. 2004), with our analysis sample yet higher in education. We were not powered to examine race/ethnicity differences, such as the frequently reported finding that increasing SES is associated with lower obesity prevalence in Black men, but with increasing obesity prevalence in Black women (Wang & Beydoun). Classification of obesity was based on self-report of weight and BMI; if anything, this is likely to result in underclassification of obesity to some extent (Taylor, Dal Grande, Gill, Chittleborough, Wilson, Adams, et al., 2006), although the use of continuous BMI meant that truly obese people were still likely to fall in the upper reaches of the continuum. Future work may wish to also use waist circumference in conjunction with measured height and weight (Wang & Beydoun 2007). Accuracy of recall of childhood social class is also moderate (Batty, Lawlor, Macintyre, Clark, & Leon, 2005) but likely to underestimate rather than overestimate associations with adult health.

Strengths of the study were the conjoint estimation of childhood SES and adult SES and personality associations, rarely possible because epidemiologic surveys usually do not include personality assessments and personality studies rarely involve national samples or include comprehensive assessment of SES (Krueger, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2000). Coverage of the majority of the adult life course ensured that findings of childhood social class effects were not based only on adults in their 20s and 30s. Comprehensive sets of personality and SES factors ensured complete and non-arbitrary coverage of phenotypic traits and SES indicators (Galobardes, Shaw, Lawlor, Lynch, & Smith, 2006a, b). Finally, to our knowledge, this study represents the first attempt of which we are aware to contextualize the links between adult body mass and childhood SES and adult SES and personality factors in the life course risk-chain theoretical framework.

Obesity affects all strata of society (Cope & Allison, 2006): although there is evidence for BMI gradients associated with childhood SES in women, not everyone who experienced childhood disadvantage develops a high body mass, and not everyone who experienced advantage enjoys a healthy weight. Personality traits in adulthood may substantially add to or detract from childhood and adult SES risks in both men and women, and bear further investigation in life course risk-accumulation models for other health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The first author's work was support in part by PHS grants T32MH073452 and by K08AG031328

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/hea/

References

- Allison DB, Heshka S, Neale MC, Lykken DT, Heymsfield SB. A genetic analysis of relative weight among 4,020 twin pairs, with an emphasis on sex effects. Health Psychology. 1994;13:362–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.4.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty GD, Lawlor DA, Macintyre S, Clark H, Leon DA. Accuracy of adults' recall of childhood social class: Findings from the aberdeen children of the 1950s study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005;59:898–903. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.030932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: Conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC. The MIDUS national survey: An overview. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well being at midlife. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2004. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brownwell K. Dieting and the search for the perfect body: Where physiology and culture collide. Behavior Therapy. 1991;22:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brummett BH, Babyak MA, Williams RB, Barefoot JC, Costa PT, Siegler IC. NEO personality domains and gender predict levels and trends in body mass index over 14 years during midlife. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:222–236. [Google Scholar]

- Carrol RJ, Ruppert D, Stefanski LA. Measurement Error in Nonlinear Models. Chapman & Hall; London: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Menendez A. Evidence from South Africa. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper; 2007. Sex differences in obesity rates in poor countries. # 13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW. Personality development across the life course: The argument for change and continuity. Psychological Inquiry. 2001;12:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(Special Issue):370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope MB, Allison DB. Obesity: Person and population. Obesity. 2006;14:156S–159S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Specter SE. Poverty and obesity: The role of energy density and energy costs. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79:6–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta-Bergman MJ. The linear interaction model of personality effects in health communication. Health Communication. 2003;15:101–115. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1501_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS. Long-term relations of personality and health: Dynamisms, mechanisms, tropisms. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:1089–1107. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Smith GD. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1) Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006a;60:7–12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.023531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Smith GD. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 2) Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006b;60:95–101. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: Extending horizons, envisioning the future. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:1650–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR, Strycker LA. Personality traits and eating habits: The assessment of food preferences in a large community sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;32:49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The development of markers for the big-five factor structure. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist. 1993;48:26–34. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene WH. Econometric Analysis. 5th ed. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. Model-based estimation of relative risks and other epidemiologic measures in studies of common outcomes and in case-control studies. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;160:301–305. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Goldberg LG, Vogt TM, Dubanoski JP. Forty years on: Teachers' Assessments of children's personality traits predict self-reported health behaviors and outcomes at midlife. Health Psychology. 2006;25:57–64. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KL, Sobal J, Frongillo EA. Gender and marital status clarify associations between food insecurity and body weight. The Journal of Nutrition. 2007;137:1460–1465. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.6.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Genes, behavior, and the social environment: Moving beyond the Nature/Nurture debate. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey RW, Rick AM. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between body mass index and marriage related factors. Obesity Research. 2002;10:809–815. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RM. Two pathways to prevention. American Psychologist. 2000;55:382–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klohe-Lehman DM, Freeland-Graves J, Anderson ER, McDowell T, Clarke KK, Hanss-Nuss H, et al. Nutrition knowledge is associated with greater weight loss in obese and overweight low-income mothers. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, WratWray RJ. Tailored and targeted health communications: Strategies for enhancing information relevance. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27(Suppl. 3):227–232. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Epidemiological personology: The unifying role of personality in population-based research on problem behaviors. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:967–998. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, Power C. Life course epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:778–783. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika SK. Obesity treatment in minorities. In: Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, editors. Handbook of obesity treatment. The Guilford Press; New York: pp. 414–446. [Google Scholar]

- Laaksonen M, Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S, Lahelma E. Multiple dimensions of socioeconomic position and obesity among employees: The Helsinki health study. Obesity Research. 2004;12:1851–1858. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The midlife development inventory (MIDI) personaltiy scales: Scale construction and scoring. Brandeis University Psychology Department; MS 062: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Langenberg C, Hardy R, Kuh D, Brunner E, Wadsworth M. Central and total obesity in middle aged men and women in relation to lifetime socioeconomic status: Evidence from a national birth cohort. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:816–822. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor DA, Batty GD, Morton SMB, Clark H, Macintyre S, Leon DA. Childhood socioeconomic position, educational attainment, and adult cardiovascular risk factors: The Aberdeen children of the 1950s cohort study. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1245–1251. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipowicz A, Gronkiewicz S, Malina RM. Body mass index, overweight and obesity in married and never married men and women in Poland. American Journal of Human Biology. 2002;14:468–475. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.10062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe MR, Miller-Kovach K, Phelan S. Weight-loss maintenance in overweight individuals one to five years following successful completion of a commercial weight loss program. Journal of Obesity. 2001;25:325–331. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren L. Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiology Reviews. 2007;29:29–48. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157:940–943. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:673–693. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DB, Jones F, Conner M, McMillan B, Ferguson E. Effects of daily hassles and eating style on eating behavior. Health Psychology. 2008;27:S20–S31. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulkki-Råback L, Elovaino M, Kivimäki M, Raitakari OT, Keltinkangas-Järvinen L. Temperament in childhood predicts body mass in adulthood: The cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Health Psychology. 2005;24:307–315. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regidor E, Gutierrez-Fisac JL, Banegas JR, Lopez-Garcia E, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Obesity and socioeconomic position measured at three stages of the life course in the elderly. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;58:488–494. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Walton KE, Bogg T. Conscientiousness and health across the life course. Review of General Psychology. 2005;9:156–168. [Google Scholar]

- Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S. Determinants of long-term weight maintenance. Acta Paediatrica. 2007;96:26–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sovio U, King V, Miettunen J, Ek E, Laitinen J, Joukamaa M, et al. Cloninger's temperament dimensions, socio-economic and lifestyle factors and metabolic syndrome markers at age 31 years in the northern Finland birth cohort 1966. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12:371–382. doi: 10.1177/1359105307074301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G, Cho JH. Socioeconomic indexes and the new 1980 census occupational classification scheme. Social Science Research. 1985;14:142–168. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R, Wells KB. Does obesity contribute as much to morbidity as poverty or smoking? Public Health. 2001;115:229–235. doi: 10.1038/sj/ph/1900764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AW, Dal Grande E, Gill TK, Chittleborough CR, Wilson DH, Adams RJ, Grant JF, Phillips P, Appleton S, Ruffin RE. How valid are self-reported height and weight? A comparison between CATI self-report and clinic measurements using a large cohort study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2006;30:238–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2006.tb00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Horst K, Oenema A, Ferreira I, Wendel-Vos W, Giskes K, van Lenthe F, et al. A systematic review of environmental correlates of obesity-related dietary behaviors in youth. Health Education Research. 2007;22:203–226. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS, Houshyar S, Prinstein M. Adolescent girls' and boys' weight-related health behaviors and cognitions: associations with reputation- and preference-based peer status. Health Psychology. 2006;25:658–663. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the united states-gender, age, socieconomic, Racial/Ethnic, and geographic characteristics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2007:1–23. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Wang YF. Socioeconomic inequality of obesity in the united states: Do gender, age, and ethnicity matter? Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]