Abstract

Imaging of the mammalian cardiac right ventricle (RV) is particularly challenging, especially when a two-dimensional method such as conventional histology is used to evaluate the morphology of this asymmetric, crescent-shaped chamber. MRI may improve the characterization of mutants with RV phenotypes by allowing analysis of the samples in any plane and by facilitating three-dimensional image reconstruction. MRI was used to examine the conditional knockout Cx43-PCKO mouse line known to have RV malformations. To help delineate the cardiovascular system and facilitate identification of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT), embryonic day (E) 17.5 embryos were perfusion fixed through the umbilical vein followed by a gadolinium-based contrast agent mixed in 7% gelatin. Micro-MRI experiments were performed at 7 T and followed by paraffin embedding of specimens, histological sectioning and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Imaging of up to four embryos simultaneously allowed for higher throughput than traditional individual imaging techniques, while intravascular contrast afforded excellent signal-to-noise characteristics. All control embryos (n=4) and heterozygous Cx43 knockout embryos (n=4) had normal-appearing right ventricular outflow tract contours by MRI. Obvious abnormalities in the RVOT, including abnormal bulging and infiltration of contrast into the wall of the RV, were seen in three out of four Cx43-PCKO mutants with MRI. Furthermore, three-dimensional reconstruction of MR images with orthogonal projections as well as maximum-intensity projection allowed for visualization of the relationship of infundibular bulging segments to the pulmonary trunk in Cx43-PCKO mutant hearts. The addition of MRI to standard histology in the characterization of RV malformations in mutant mouse embryos aids in the assessment and understanding of morphologic abnormalities. Flexibility in the viewing of MR images, which can be retrospectively sectioned in any desired orientation, is particularly useful in the investigation of the RV, an asymmetric chamber that is difficult to analyze with two-dimensional techniques.

Keywords: embryo, transgenic, cardiac, development, phenotype, mouse, micro-MRI, ex vivo

INTRODUCTION

The cardiac right ventricle (RV) is a crescent-shaped, asymmetric chamber that is located ventrally and caudally to the left ventricle (LV). Inflow into the RV from the right atrium via the tricuspid valve occurs at the right dorsal aspect of the heart, while the RV outflow tract (OT) is situated ventrally and cranially. The complicated structure of the RV stands in contradistinction to that of the LV, which is a more symmetric and thicker-walled muscular chamber. Consequently, assessing the RV chamber with standard techniques that limit investigation to a two-dimensional plane, such as conventional histology, is a difficult proposition that may result in loss of important three-dimensional structural data. While standard histology provides superb spatial resolution and ultrastructural information, histological examination is limited to the plane of sectioning. Three-dimensional reconstruction of histological images is time consuming and severely limited by problems of registration (1,2). Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging may be an ideal complementary modality to histology for the examination of mutant phenotypes that primarily affect RV morphogenesis (3).

Image sets obtained using MRI can be sectioned and resectioned non-destructively in any orientation of interest. MR images can be used to generate three-dimensional projections, without the registration issues that histological sectioning can introduce. Furthermore, with the addition of intravascular contrast, the internal contour of the RV can be examined even on magnets with modest field strength, thereby facilitating the characterization of complicated RV morphologic phenotypes. Indeed, MR imaging has proven to be a superb imaging technique for evaluating abnormalities of the RV in conditions such as arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (4,5) and complex congenital heart disease (6), as well as in the evaluation of experimental models of heart disease (7).

Previous studies using MR to analyze the cardiac phenotype of germline Cx43 knockout embryos were performed with custom-made coils and a high field strength (9.4 T) (8). Investigations with field strengths in excess of 11 T have been used to describe the normal embryonic development of the mouse (9), to characterize the effect of teratogens on the mouse embryo (10) and to increase throughput by imaging multiple genetically manipulated embryos simultaneously (11–15). With their 7 T MR system, a widely available field strength for animal research purposes (16,17), the present authors wished to investigate whether it was possible to analyze developmental phenotypes of the RV while improving throughput compared with conventional MRI experiments.

To investigate the ability of MR imaging with intravascular contrast enhancement to evaluate mutant RV phenotypes, embryonic day (E) 17.5 mouse embryos with neural tube-specific loss of the connexin43 gap junction protein (‘Cx43-PCKO’ mice) were chosen for examination. At this stage, these mutant mice have aberrant development of the RVOT consisting of a grossly bulging appearance of the myocardium above the area of the outflow tract with associated ‘conotruncal pouching’ and trabecular in-growth into the outflow tract (18). The phenotype of the Cx43-PCKO mice is similar to that of the germline Cx43 knockout, which has been previously analyzed by µMRI using a field strength of 9.4 T and individual imaging of each embryo (8).

In the Cx43-PCKO mouse line the aim was to characterize RVOT morphology using the 7 T system while simultaneously imaging four embryos at an imaging resolution of 50µm. It was found that imaging with MR after injection of intravascular contrast agents accentuated the anatomy of cardiac chambers and the outflow tract and afforded excellent visualization of the abnormally bulging infundibular segment in mutant embryos. By providing for the interrogation of image sets in multiple planes of orientation, MR allowed for a precise characterization of how bulging infundibular segments affected the overall integrity of the outflow tract. Differences in OT morphology between mutant and control hearts were also observed at an imaging resolution of 100µm, which could substantially reduce the imaging time. Thus, MR imaging with intravascular contrast injection is of substantial value in the evaluation of a mutant phenotype that affects primarily the RV.

METHODS

Mouse model

Mice harboring a Cx43 gene locus flanked by LoxP sites (‘Cx43 floxed mice’) (19) were crossed with P3pro-Cre transgenic mice (20,21) to generate a mutant line with P3pro-Cre-mediated conditional knockout of Cx43 (Cx43-PCKO) (18). P3pro-Cre transgenic mice were obtained courtesy of Dr. J. A. Epstein (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). The P3pro-Cre trans-gene is driven by the proximal 1.6 kb of the Pax3 promoter. Cx43-PCKO mice have abnormal cardiac morphogenesis characterized grossly by infundibular bulging similar to that of the germline Cx43 KO mouse, but Cx43-PCKO mice are easier to breed than the germline mutants (22,23). Cx43-PCKO mice carried one allele in which the Cx43 open reading frame was deleted, or ‘floxed-out’, in the germline. Mice that were wild type at the Cx43 locus or that did not carry the Cre transgene and a ‘floxed-out’ allele were used as controls. Heterozygous Cx43 knockout embryos served as an additional study group.

PCR and Southern blotting of yolk sac DNA was used to establish genotypes. All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the New York University School of Medicine and the Veterans Administration New York Harbor Healthcare Medical Center (New York, NY).

Perfusion-fixation and injection of intravascular contrast agent

Preparation for MR microimaging was carried out in a similar manner to that described by Smith et al. (24–26). Conceptuses at E17.5 were removed from euthanized pregnant females and placed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. Individually, conceptuses were placed on a glass dish lined with Sylgard 184 silicone elastomer base (Dow Corning, Midland, MI), moistened with phosphate-buffered saline and warmed to 37°C. The yolk sac was removed from around the embryo, carefully separated from the placenta and processed for genotyping. Under a dissecting microscope, the umbilical vessels were incised and the umbilical vein was cannulated with a glass micropipette attached via a length of tubing to an IPC peristaltic pump (Ismatec SA, Glattbrugg, Switzerland). Phosphate-buffered saline with heparin (5000 U/L) was infused through the umbilical vein to clear the vasculature of blood, followed by perfusion with 2% glutaraldehyde/1% formalin and lastly a gadolinium-based MR contrast agent (BSA-DTPA-Gd; Sigma-Aldrich) mixed in 7% gelatin. Food coloring (McCormick & Co., Inc., Hunt Valley, MD) was added to the fixative and contrast agent to verify perfusion. The umbilical vessels were then ligated and the embryo was stored in 2% glutaraldehyde/1% formalin at 4°C.

Magnetic resonance imaging of mutant embryos

MR microimaging experiments were performed using a 7 T, 200mm horizontal bore, superconducting magnet (Magnex, Abingdon, UK) with an actively shielded gradient coil (120mm ID, 250 mT/m gradient strength, 200µs rise time). A recirculating water-cooled chiller (Neslab, Newington, NH) was used to prevent over-heating of the gradient insert while achieving the highest duty cycle by setting the temperature to 10°C. A quadrature litz coil (Doty Scientific, Columbia, SC) designed for mouse head imaging (ID=25 mm; length L=22 mm) and tuned to 301MHz was used to incorporate a 30 cc syringe (24mm outer diameter, 20.5mm inner diameter; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). To increase throughput, up to four E17.5 embryos were glued into place (Krazy Glue; Elmer’s Products, Inc., Columbus, OH) in the 30 cc syringe, one in each quadrant of the plunger. The mouse embryo samples were then embedded in 3% low-melt agarose (SeaPlaque®; Rockland, Maine, USA) to prevent dehydration during long image acquisition times.

Imaging was performed overnight with a 3D T1-weighted gradient echo (echo time TE=5 ms; repetition time TR=50 ms; flip angle FA=35°; FOV=25.6 mm; matrix size=5123; isotropic resolution =50µm; number of averages Nav=4; total imaging time=14 h, 35 min) to provide adequate spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The SNR was defined as the average signal intensity of the sample divided by the standard deviation of the background signal from air. Based on prior experience, the goal was to maintain an SNR of greater than 30 (27,28). In order further to optimize image quality and more easily identify the vascular structures while maintaining myocardial delineation, a contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) of greater than 5 was aimed for. The goal for CNR was based on Rose’s criterion for the minimum ratio that permits the visibility of an object image in a homogeneous background (29). The CNR was assessed as the difference in SNR between intravascular signal and myocardial tissue in the embryos using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Four of the embryos were also imaged at an isotropic resolution of 100µm (identical sequence parameters; matrix size=2563), adding two additional hours to the total imaging time. The 100µm image dataset was sub-sequently zero filled to 5123 matrix size to provide an isotropic resolution of 50µm.

For three-dimensional rendering of the embryo vasculature, MR images were reconstructed using three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection (MIP). Image quality of three-dimensional datasets was adjusted by thresholding prior to MIP and contrast refinement. All image analysis and visualization was performed using Analyze 5.0 software (Analyze; Biomedical Imaging Resource, Mayo Foundation, Rochester, MN).

Preparation of whole-mount hearts

To aid in the visual interpretation of three-dimensional reconstructions of MR data, neonatal control and Cx43-PCKO hearts were excised, rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline and imaged using a Leica MZ12.5 stereomicroscope equipped with a DEI-750D video camera (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Images of whole-mount neonatal control and Cx43-PCKO hearts are presented in tandem with three-dimensional reconstructed MR images from E17.5 embryos with matching genotypes.

Histological assessment of perfused embryos

After MR imaging, specimens were dehydrated in ethanol, embedded in paraffin blocks and sectioned at a thickness of 5 µm. Selected sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using a Zeiss HMS series programmable slide stainer.

RESULTS

Improved throughput with excellent signal-to-noise characteristics in MR imaging of multiple embryos with injected intravascular contrast agent

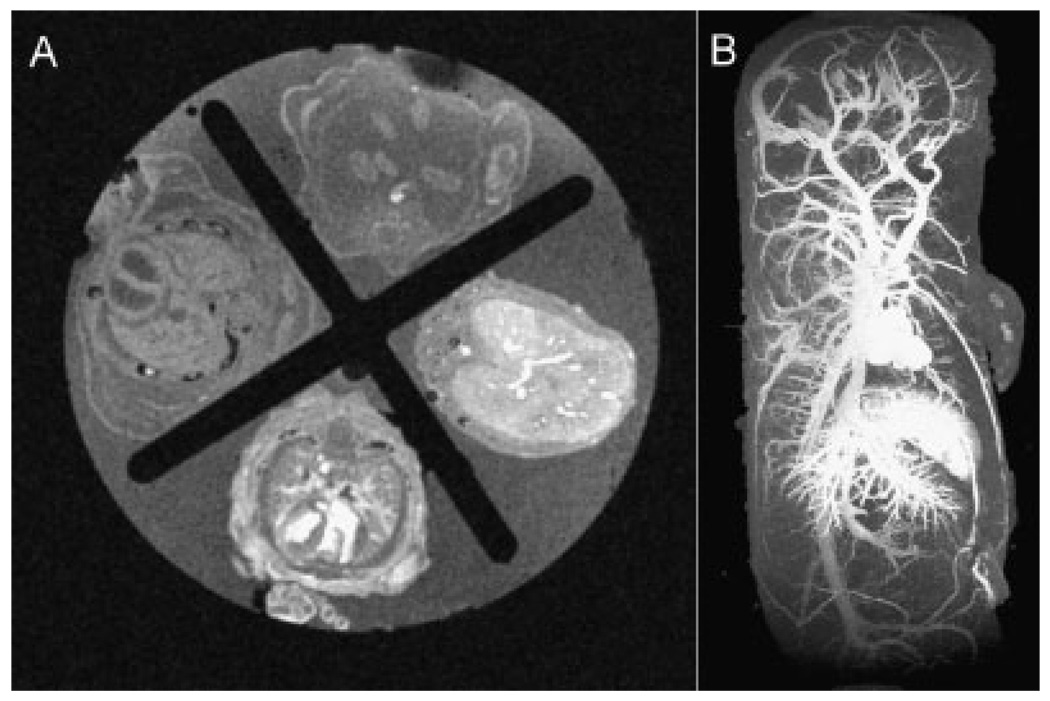

To improve the throughput of the present imaging technique over traditional imaging of individual embryos, four embryos at a time were embedded in 3% low-melt agarose using a 30 cc syringe as a mold for simultaneous imaging of multiple embryos with a variety of genotypes [Fig. 1(A)]. In addition to improving throughput, simultaneous imaging of multiple embryos reduced variability of image acquisition among individual embryos. Furthermore, injection of contrast agent afforded excellent SNR characteristics in the intravascular space. The mean SNR for the contrast-enhanced intravascular space was almost twice as high as that calculated for the myocardial tissue. Nonetheless, myocardial tissue had a sufficiently high SNR to enable distinction of the heart muscle from background noise.

Figure 1.

MR imaging of embryonic vasculature. (A) Axial section of a simultaneous four-embryo imaging set-up using a 30 cc syringe enabling a higher throughput and a more robust comparative study with less variability among littermates. (B) Highly detailed vascular enhancement (50µm isotropic resolution) of an E17.5 embryo perfused and fixed through the umbilical vein after maximum-intensity projection image post-processing.

In addition to a high SNR, images were optimized to maintain a high CNR between the intravascular space and myocardium, allowing highly detailed imaging of cardiovascular structures [Fig. 1(B) and Table 1]. For the purpose of comparison, the leftmost embryo in Fig. 1(A) was not injected with contrast agent. Thus, simultaneous MR imaging of multiple embryos with injected intravascular contrast enhanced throughput while maintaining excellent SNR and CNR characteristics of the resulting images.

Table 1.

Summary of signal-to-noise ratio and contrast-to-noise ratio measurements from intravascular space and myocardial muscle

| Signal-to-noise ratio |

Contrast-to-noise ratio |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region of interest | Intravascular space | Myocardial muscle | Intravascular space to myocardium |

| Mean | 35 | 16 | 19 |

| Standard deviation | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Number of samples | 8 | 8 | 8 |

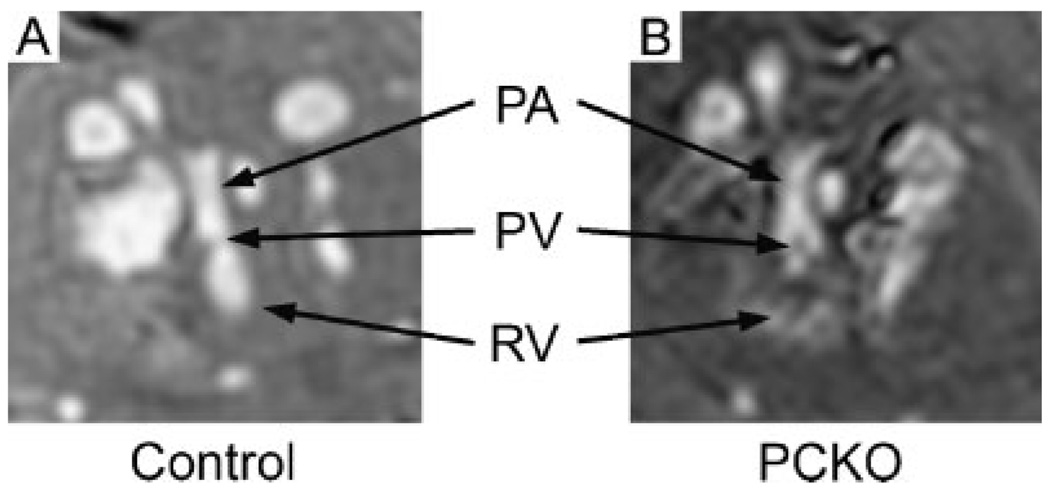

Abnormal RVOT contour is well delineated by MR in the Cx43-PCKO mutants

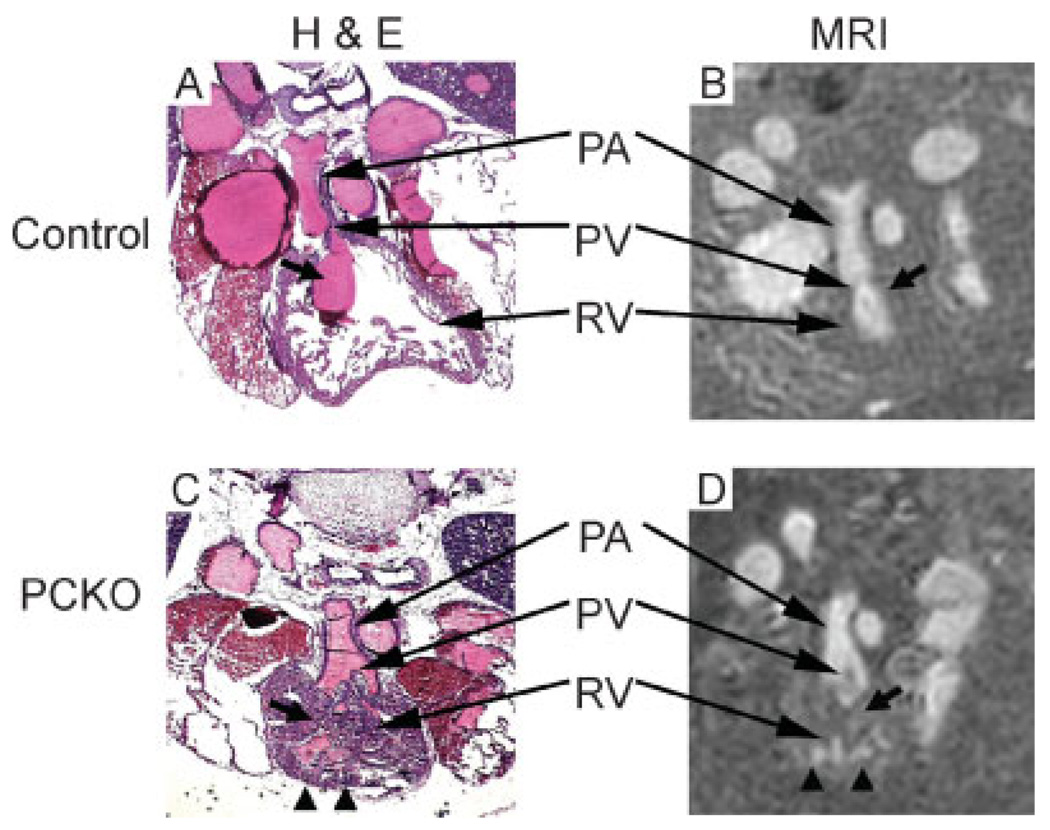

To characterize the right ventricular abnormalities of Cx43-PCKO hearts, initial focus was on the RVOT, which develops abnormal trabeculation and dilatation in neonatal Cx43-PCKO and germline Cx43-null mice. MR images of the RVOT in all control hearts (n=4) and heterozygous Cx43 knockout hearts (n=4) demonstrated a smooth luminal contour that was surrounded by a thick, muscular cuff of right ventricular tissue. Histologically, as on MR images, the lumen of the RVOT in the control hearts was free of obstructive trabeculation [small arrows in Figs 2(A) and (B)]. In contrast to control hearts, histological and MR images of the Cx43-PCKO heart demonstrated dense trabeculations projecting into the lumen of the RVOT [small arrows in Figs 2(C) and (D)], potentially obstructing the flow of blood out of the heart and into the pulmonary trunk. The RV tissue appeared less homogeneous in MR images of Cx43-PCKO hearts than the RV wall in control hearts, a difference likely due to infiltration of contrast into the wall of the RV [arrowheads in Figs 2(C) and (D)]. Infiltration of contrast material deep into the wall of the RV in the mutant hearts was consistent with extensive blind-ended lacunae and sinusoidal cavities observed previously in the Cx43-null RVOT (30). Morphologic abnormalities of the RVOT were apparent in three of the four mutant embryos on MR images. Therefore, MR imaging and intravascular injection of contrast could be used to identify morphologic abnormalities of the embryonic RVOT.

Figure 2.

Histological and (50µm)3 MR imaging of right ventricular outflow tracts (RVOT) of control and mutant (Cx43-PCKO) mice. The RVOT of a control embryo has a discrete smooth contour without trabeculation that is clearly evident in histological (A) and MR images (B). Histological and MR imaging of the mutants [(C) and (D) respectively] shows clear differences from the controls, including extensive trabeculation in the RVOT (small arrows) and infiltration of contrast into the wall of the RV (arrowheads). Note that in histological sections residual MR contrast material is seen [pink intravascular substance in (A) and (C)]. Incomplete deposition of residual contrast material is likely an artifact of processing of the histological specimens. PA, pulmonary artery; PV, pulmonic valve; RV, right ventricle.

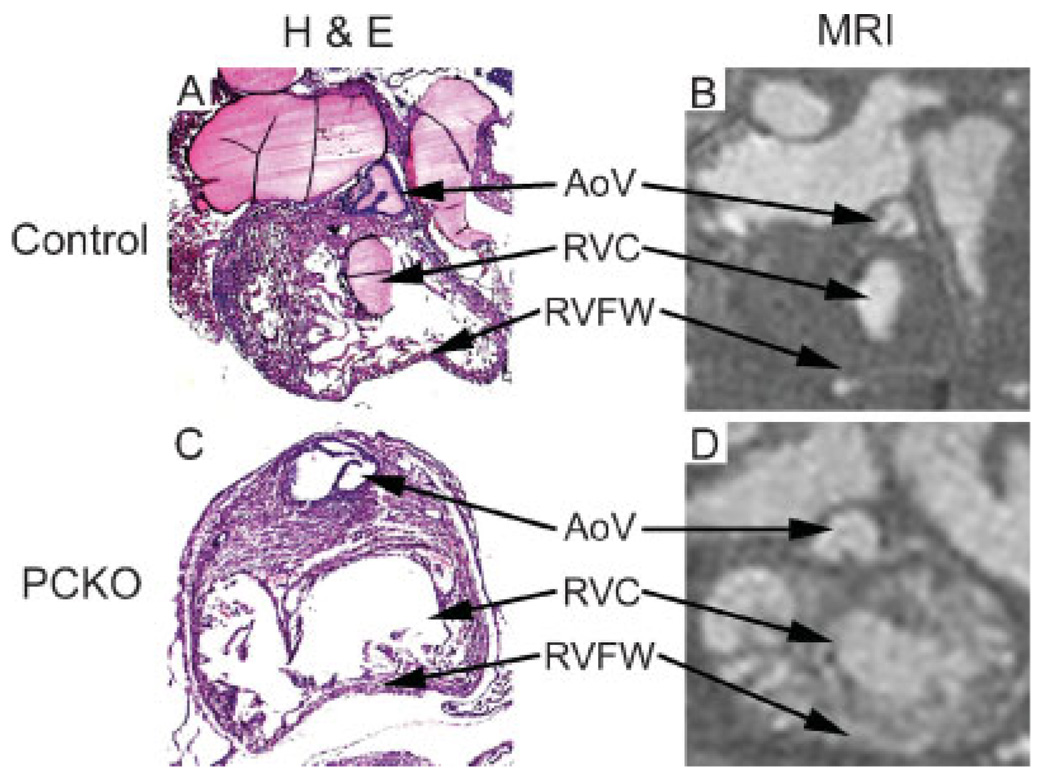

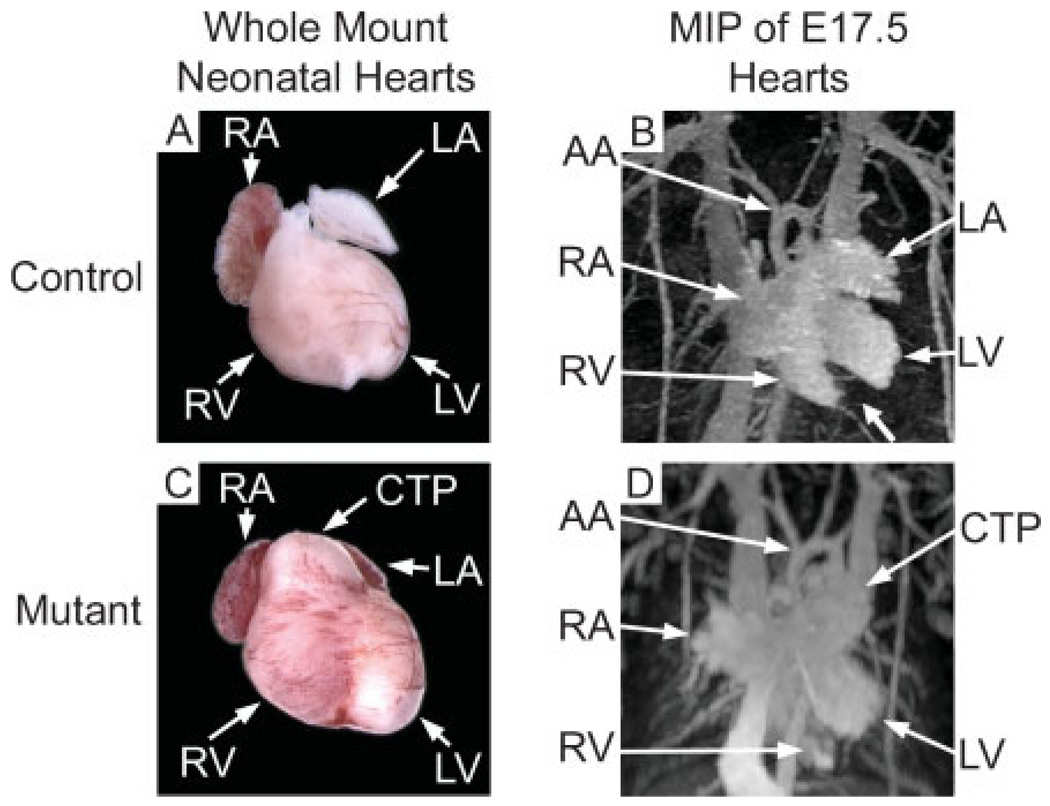

MR images provide excellent characterization of the Cx43-PCKO infundibulum

The infundibulum, or muscular portion of the RV that leads into the OT, is the region of the Cx43-PCKO and germline Cx43-null hearts that is most obviously and grossly affected by the mutant phenotype (Fig. 3). The infundibulum in these Cx43 mutant lines develops large bulging segments bilaterally, termed ‘conotruncal pouches’ (31), that grossly disrupt the contour of the heart. MR images of Cx43-PCKO hearts at the level of the infundibulum showed important differences between the mutant and control hearts. While the control infundibulum had a smooth lumen encircled by a thick muscular layer [Fig. 3(B)], the Cx43-PCKO infundibulum had bulging, thin-walled aneurysmal segments and extensive extravasation of contrast into the RV wall [Fig. 3(D)]. Thus, as observed with imaging at the level of the pulmonic valve, MR yields excellent images detailing morphologic abnormalities of the infundibulum.

Figure 3.

Histological and MR sectioning through the RV infundibulum in control and Cx43-PCKO hearts. Control and mutant hearts appear similar on histological sectioning at this level [(A) and (C) respectively], but MR images show important differences. MR images demonstrate the solid, muscular wall of the RV at this level in controls (B), whereas in the mutant the RV wall has an aneurysmal segment with extensive mural infiltration of contrast (D). Residual MR contrast material is seen in the histological section in (A). AoV, aortic valve; RVC, right ventricular chamber; RVFW, right ventricular free wall.

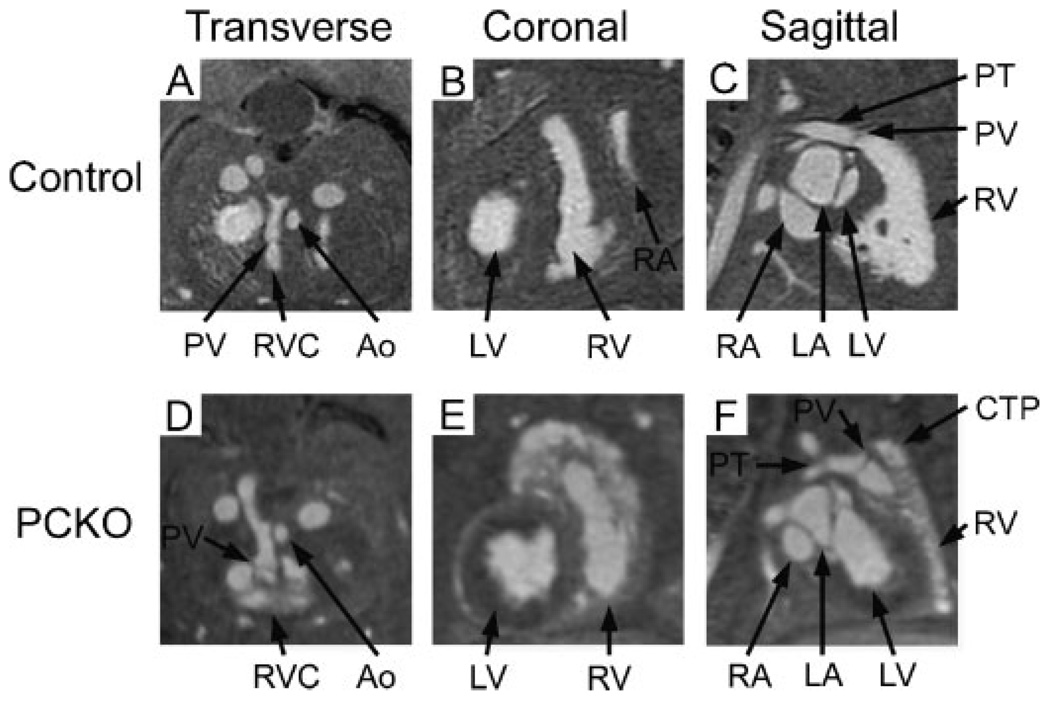

Orthogonal MR images define the extent of infundibular bulging and the relationship to RVOT

To define the extent of the infundibular bulging segment and its relationship to the RVOT, orthogonal views of the MR images were interrogated. Starting from the transverse projection [Figs 4(A) and (D)], the RVOT was identified and coronal and sagittal projections through the same point were examined. This simplified the identification of various structures, such as the infundibular segment, on each projection. In the coronal view, the mutant infundibulum extended cranially to the left ventricle and to the left of the pulmonary trunk, thus displacing the left atrial appendage [compare Figs 4(B) and (E)]. The mutant infundibulum could be seen extending ventrally and cranially relative to the RVOT in the sagittal image [Fig. 4(F)]. The corresponding view in a control embryo demonstrated a narrower infundibulum that tapers into the pulmonic valve and pulmonary trunk [Fig. 4(C)]. By allowing the RVOT from individual mutants to be viewed in multiple sectioning planes, MR imaging improved the understanding of the PCKO RV malformation.

Figure 4.

Orthogonal images of control and mutant hearts demonstrate the relationship of bulging infundibular segments to the RVOT. Transverse, coronal and sagittal views of MR images show that in comparison with the control [(A), (B) and (C) respectively] the contour of the mutant RVOT and infundibulum is substantially altered [(D), (E) and (F)]. PV, pulmonic valve; RVC, right ventricular chamber; Ao, aorta; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; PA, pulmonary artery; LAA, left atrial appendage; DAo, descending aorta; CTP, conotruncal (infundibular) pouch.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of MR images shows gross structural changes in the Cx43-PCKO heart

To investigate how altered RV architecture in the Cx43-PCKO heart affected the gross structural status of the mutant heart, three-dimensional MIP reconstruction of MR images was performed (Fig. 5). As a guide to orientation, MR images are presented in juxtaposition to whole-mount control [Fig. 5(A)] and mutant hearts [Fig. 5(C)]. In MR images of a control heart viewed in the left anterior oblique projection [Fig. 5(B)], both ventricles were distinctly visible and clearly separated by the interventricular septum (small arrow). The aortic arch was seen to be cranial to the heart and the left atrium projected just cranially and to the left of the OT. In contrast, the relationship of the right to left ventricle in the MR images of the mutant heart was altered such that the interventricular septum was no longer visible from the left anterior oblique projection [Fig. 5(D)]. The grossly enlarged infundibulum and RVOT in the mutant heart extended cranially and to the left of the heart, nearly obstructing the view of the aortic arch and displacing the left atrium. Three-dimensional reconstruction of MR images was particularly valuable for visualizing the altered architecture of the RV and its relationship to neighboring structures in a non-destructive manner.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection MR images of control and Cx43 mutant hearts. To aid in orientation, whole-mount neonatal control (A) and Cx43 mutant hearts (C) are presented adjacent to maximum-intensity projection MR images of separate E17.5 control and Cx43 mutant embryos (the whole-mount neonatal heart shown in (C) is a germline Cx43-null mutant shown for illustrative purposes). The aortic arch (AA) is easily visible and unobstructed in three-dimensional MR images of the control heart (B). In contrast, the mutant heart (D) has a prominent conotruncal (infundibular) pouch (CTP) that extends cranially almost to the level of the aortic arch, partially obstructing it from view and displacing the left atrium. Additionally, while the interventricular septum is clearly visible in MR images of control hearts [small arrow in (B)], the misshapen mutant RV partially blocks the septum from view (D). SVC, superior vena cava; IVC, inferior vena cava; V, ventricle.

MR imaging at an isotropic resolution of (100µm)3 demonstrates RVOT abnormalities in the mutant hearts

To determine whether RVOT abnormalities could be detected in the Cx43-PCKO hearts with a shorter imaging time, the embryos were studied at an isotropic resolution of (100µm)3. In spite of a reduction in total imaging time for this experimental protocol to 2 h, abnormal phenotypic features of the mutant RVOT such as infundibular bulging were clearly apparent when compared with control hearts. In addition, mural extravasation of contrast in the RVOT was seen in the mutant hearts, but not in the controls (Fig. 6). As a result of injection of intravascular contrast and the flexibility afforded by MR image processing, determining the phenotype of mutants with morphologic abnormalities of the RV could be accomplished in multiple embryos in as little as 2 h.

Figure 6.

MR images of control and mutant embryos acquired in 2 h at (100 µm)3 isotropic resolution. Control (A) and mutant hearts (B) were imaged for 2 h at an isotropic resolution of (100µm)3. Sections at the level of the RVOT demonstrate loss of tissue integrity in the mutant RV wall. PA, pulmonary artery; PV, pulmonic valve; RV, right ventricle.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the versatile and detailed nature of MR characterization of RV abnormalities in embryos from the mutant Cx43-PCKO line. To investigate RV morphologic abnormalities in a mutant line, features from published MR imaging protocols such as simultaneous imaging of multiple embryos (11–13) and injection of intravascular contrast to facilitate visualization of cardiac chambers and vascular structures (24) were combined. MR imaging has been used previously to examine the cardiac phenotype of the germline Cx43 knockout mouse, but this study of E14.5 embryos utilized a magnet with a field strength of 9.4 T, as well as custom-made coils (8). By using an 11.5 T magnet, Schneider et al. obtained excellent images of the embryonic mouse heart without the use of intravascular contrast (11–13). Since resources are limited and many academic centers do not have magnets with field strengths of 9.4 T and above, the present authors endeavored to design a protocol that would enable MR imaging of the mutant embryonic mouse heart with their 7 T MR system and a commercially available coil. By imaging multiple embryos simultaneously and by using intravascular contrast, it was possible to maintain adequate throughput and obtain excellent CNR characteristics between the intravascular space and the myocardium with the 7 T magnet and ‘off-the-shelf’ equipment.

Imaging of the RV using standard histology is complicated by the asymmetric structure of the RV. Unlike the RV, the left ventricle is a concentrically shaped, thick-walled chamber, and assumptions about its three-dimensional shape can be made on the basis of a two-dimensional image. Since the RV is a thin-walled chamber that is shaped like a crescent, it is more difficult to image reliably and reproducibly using a two-dimensional technique such as histology since the perceived shape of the RV chamber is dependent on the plane of sectioning. The difficulties in visualizing the RV are ameliorated with MR imaging, since orthogonal projections can be used to standardize views of the RV for a more robust comparison. Furthermore, maximum-intensity projections of MR images can improve the visualization of RV malformations by demonstrating the relationship of segmental abnormalities to other structures of the heart in three dimensions. The combination of intravascular contrast with MR imaging is particularly important for cardiac phenotyping of mutant mice, since it allows for the non-destructive three-dimensional data visualization of the heart in its vascular context. This enables the investigator to determine the precise orientation for subsequent histological sectioning of the embryo and whether vascular abnormalities are present without dissecting the embryo.

Injection of intravascular contrast via the umbilical vein can function to emphasize aneurysmal segments of the RV by expanding weakened regions under positive pressure. Thus, the thinned infundibulum of the Cx43-PCKO becomes maximally expanded and easily visualized when subjected to positive pressure during the fixation and contrast injection procedure. This process may actually result in overexpansion of the infundibulum, artifactually displacing the trabeculae in the RV chamber away from the RVOT, where they may otherwise obstruct blood flow during systole (32). In contrast, thinned RV infundibular tissue, like that seen in some of the Cx43-PCKO samples, may contract and collapse when dehydrated and processed prior to embedding for histological analysis. Most likely for these reasons, infundibular abnormalities were detected more readily by MR imaging than by histological analysis in this series of Cx43-PCKO embryos.

Advances in image processing software and three-dimensional reconstruction have improved the ability to characterize RV abnormalities by MR. Previously, RVOT dilatation was demonstrated in Cx43-null embryos using MR imaging (8). In the present study, images of mutant hearts revealed more subtle but important findings in addition to altered RVOT contour, including the ingrowth of trabeculae into the RV cavity and extravasation of contrast into the RV wall. Extensive trabeculation, changes in the shape of the RVOT and loss of integrity of the RV wall were apparent even in images acquired with an isotropic resolution of (100 µm)3. These images were acquired in 2 h, a considerable improvement over the 14.5 h total imaging time necessary to obtain an isotropic resolution of (50 µm)3. Alternatively, to increase throughput further, a larger RF coil may be used to accommodate a greater number of embryos while compensating SNR loss through averaging over longer imaging times. Thus, the present protocol is particularly appropriate for use by investigators studying cardiac phenotypes in mutant mice at centers with core facilities that have a magnet with limited field strength (<9.4 T) and where imaging time is in high demand.

Clinically, MR imaging provides critical complementary data in the work-up of patients with congenital malformations involving the RV (6). MR is the preferred non-invasive imaging technique in the diagnosis and evaluation of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy, a fibro-fatty replacement and thinning of the RV myocardial tissue that provides a pathognomonic MR appearance (4,5). Furthermore, MR imaging is particularly useful in the evaluation of RV size and function in genetically altered mice and experimental mouse models of heart disease (7,33).

The Cx43-PCKO line was chosen for this study specifically because the most obvious characteristic of the mutant phenotype is gross deformation of the RV. This mutant line provided an opportunity to examine the ability of MR imaging to characterize morphologic abnormalities in the RV. The present authors have previously shown that Cx43-PCKO mice, in which Cx43 expression is conditionally ablated in the thoracic neural tube, develop abnormalities of the RV infundibulum (with approximately 90% penetrance) that appear similar to those of the germline Cx43 KO. Neural tube-specific loss of Cx43 in the Cx43-PCKO line results in an aberrant migratory population of neuroepithelium-derived cells, some of which infiltrate the OT of the heart, presumably with a deleterious impact on the structural integrity of the infundibulum (18). The Cx43-PCKO line was chosen instead of the germline Cx43-null line because breeding of the Cx43-PCKO line is considerably easier.

In conclusion, an MR imaging protocol has been developed using widely accessible technology and commercially available equipment that maintains acceptable throughput and signal-to-noise characteristics. RV abnormalities in the Cx43-PCKO embryos, such as abnormal RVOT bulging, trabecular in-growth and extravasation of contrast into the RV wall, can be reliably visualized with this MR imaging protocol. MR imaging, by enabling three-dimensional visualization and non-destructive sectioning in any plane of interest, provides an important complement to standard histology in the characterization of RV malformations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants HL081336 (DEG) and HL078665 (DHT) and a Grant-in-Aid from the American Heart Association (DEG). The authors thank Dr Bradley R. Smith for advice and initial training in the embryo perfusion and gadolinium-enhanced MRI protocols. They also thank Ms Fang-yu Liu and Ms Jie Zhang for technical assistance with embryo perfusion.

Abbreviations used

- AA

aortic arch

- Ao

aorta

- AoV

aortic valve

- CTP

conotruncal infundibular pouch

- Cx43

connexin43

- Cx43-PCKO

P3pro-Cre-mediated conditional knockout of Cx43

- Dao

descending aorta

- E

embryonic day

- IVC

inferior vena cava

- LA

left atrium

- LAA

left atrial appendage

- LV

cardiac left ventricle

- MIP

maximum-intensity projection

- OT

outflow tract

- PA

pulmonary artery

- PV

pulmonic valve

- RV

cardiac right ventricle

- RVC

right ventricular chamber

- RVFW

right ventricular free wall

- RVOT

right ventricular outflow tract

- SVC

superior vena cava

- V

ventricle

Footnotes

This research was presented, in part, at the 14th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA, 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arsigny V, Pennec X, Ayache N. Polyrigid and polyaffine transformations: a novel geometrical tool to deal with non-rigid deformations - application to the registration of histological slices. Med. Image Anal. 2005;9:507–523. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Streicher J, Weninger WJ, Muller GB. External marker-based automatic congruencing: a new method of 3D reconstruction from serial sections. Anat. Rec. 1997;248:583–602. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199708)248:4<583::AID-AR10>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari VA, Fisher SA. Imaging the embryonic heart: how low can we go? How fast can we get? J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:141–143. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(02)00306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tandri H, Saranathan M, Rodriguez ER, Martinez C, Bomma C, Nasir K, Rosen B, Lima JA, Calkins H, Bluemke DA. Noninvasive detection of myocardial fibrosis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy using delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005;45:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tandri H, Friedrich MG, Calkins H, Bluemke DA. MRI of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2004;6:557–563. doi: 10.1081/jcmr-120030583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davlouros PA, Niwa K, Webb G, Gatzoulis MA. The right ventricle in congenital heart disease. Heart. 2006;92 Suppl. 1:i27–i38. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.077438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiesmann F, Frydrychowicz A, Rautenberg J, Illinger R, Rommel E, Haase A, Neubauer S. Analysis of right ventricular function in healthy mice and a murine model of heart failure by in vivo MRI. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;283:H1065–H1071. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00802.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang GY, Wessels A, Smith BR, Linask KK, Ewart JL, Lo CW. Alteration in connexin 43 gap junction gene dosage impairs conotruncal heart development. Dev. Biol. 1998;198:32–44. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhenain M, Ruffins SW, Jacobs RE. Three-dimensional digital mouse atlas using high-resolution MRI. Dev. Biol. 2001;232:458–470. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugimoto M, Manabe N, Morita M, Tanaka T, Okamoto R, Imanishi S, Miyamoto H. Availability of NMR microscopic observation of mouse embryo disorder: examination in malformations induced by maternal administration of retinoic acid. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2002;64:427–433. doi: 10.1292/jvms.64.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider JE, Bamforth SD, Farthing CR, Clarke K, Neubauer S, Bhattacharya S. High-resolution imaging of normal anatomy, and neural and adrenal malformations in mouse embryos using magnetic resonance microscopy. J. Anat. 2003;202:239–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider JE, Bamforth SD, Farthing CR, Clarke K, Neubauer S, Bhattacharya S. Rapid identification and 3D reconstruction of complex cardiac malformations in transgenic mouse embryos using fast gradient echo sequence magnetic resonance imaging. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:217–222. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(02)00291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider JE, Bamforth SD, Grieve SM, Clarke K, Bhattacharya S, Neubauer S. High-resolution, high-throughput magnetic paragraph sign resonance imaging of mouse embryonic paragraph sign anatomy using a fast gradient-echo sequence. Magma. 2003;16:43–51. doi: 10.1007/s10334-003-0002-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider JE, Bhattacharya S. Making the mouse embryo transparent: identifying developmental malformations using magnetic resonance imaging. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today. 2004;72:241–249. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider JE, Bose J, Bamforth SD, Gruber AD, Broadbent C, Clarke K, Neubauer S, Lengeling A, Bhattacharya S. Identification of cardiac malformations in mice lacking Ptdsr using a novel high-throughput magnetic resonance imaging technique. BMC Dev. Biol. 2004;4:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-4-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapon C, Franconi F, Roux J, Marescaux L, Le Jeune JJ, Lemaire L. In utero time-course assessment of mouse embryo development using high resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Anat. Embryol (Berl) 2002;206:131–137. doi: 10.1007/s00429-002-0281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogers B, Gross D, Lehmann V, Zick K, De Groot HJ, Gitten-berger-De Groot AC, Poelmann RE. Magnetic resonance microscopy of mouse embryos in utero. Anat. Rec. 2000;260:373–377. doi: 10.1002/1097-0185(20001201)260:4<373::AID-AR60>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, Liu F, Schneider AE, St Amand T, Epstein JA, Gutstein DE. Distinct cardiac malformations caused by absence of connexin 43 in the neural crest and in the non-crest neural tube. Development. 2006;133:2063–2073. doi: 10.1242/dev.02374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutstein DE, Morley GE, Tamaddon H, Vaidya D, Schneider MD, Chen J, Chien KR, Stuhlmann H, Fishman GI. Conduction slowing and sudden arrhythmic death in mice with cardiac-restricted inactivation of connexin43. Circ. Res. 2001;88:333–339. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein JA, Li J, Lang D, Chen F, Brown CB, Jin F, Lu MM, Thomas M, Liu E, Wessels A, Lo CW. Migration of cardiac neural crest cells in Splotch embryos. Development. 2000;127:1869–1878. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.9.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Chen F, Epstein JA. Neural crest expression of Cre recombinase directed by the proximal Pax3 promoter in transgenic mice. Genesis. 2000;26:162–164. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<162::aid-gene21>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ackert CL, Gittens JE, O’Brien MJ, Eppig JJ, Kidder GM. Intercellular communication via connexin43 gap junctions is required for ovarian folliculogenesis in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 2001;233:258–270. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roscoe WA, Barr KJ, Mhawi AA, Pomerantz DK, Kidder GM. Failure of spermatogenesis in mice lacking connexin43. Biol. Reprod. 2001;65:829–838. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.3.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith BR, Johnson GA, Groman EV, Linney E. Magnetic resonance microscopy of mouse embryos. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:3530–3533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith BR. Magnetic resonance imaging analysis of embryos. Methods Mol. Biol. 2000;135:211–216. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-685-1:211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith BR. Magnetic resonance microscopy in cardiac development. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2001;52:323–330. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20010201)52:3<323::AID-JEMT1016>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson G, Wadghiri YZ, Turnbull DH. 2D multislice and 3D MRI sequences are often equally sensitive. Magn. Reson. Med. 1999;41:824–828. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199904)41:4<824::aid-mrm23>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wadghiri YZ, Johnson G, Turnbull DH. Sensitivity and performance time in MRI dephasing artifact reduction methods. Magn. Reson. Med. 2001;45:470–476. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200103)45:3<470::aid-mrm1062>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brandan ME, Ramirez RV. Evaluation of dual-energy subtraction of digital mammography images under conditions found in a commercial unit. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006;51:2307–2320. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/9/014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker DL, Vacha SJ, Kirby ML, Lo CW. Connexin43 deficiency causes dysregulation of coronary vasculogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2005;284:479–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lo CW, Wessels A. Cx43 gap junctions in cardiac development. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 1998;8:264–269. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(98)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reaume AG, de Sousa PA, Kulkarni S, Langille BL, Zhu D, Davies TC, Juneja SC, Kidder GM, Rossant J. Cardiac malformation in neonatal mice lacking connexin43. Science. 1995;267:1831–1834. doi: 10.1126/science.7892609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Souza AP, Cohen AW, Park DS, Woodman SE, Tang B, Gutstein DE, Factor SM, Tanowitz HB, Lisanti MP, Jelicks LA. MR imaging of caveolin gene-specific alterations in right ventricular wall thickness. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2005;23:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]