Abstract

Objective

This paper is aimed at establishing infrared spectral patterns for the different tissue types found in, and for different stages of disease of squamous cervical epithelium. Methods for the unsupervised distinction of these tissue types are discussed.

Methods

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) maps of the squamous and glandular cervical epithelium, and of the cervical transformation zone, were obtained and analyzed by multivariate unsupervised hierarchical cluster methods. The resulting clusters are correlated to the corresponding stained histopathological features in the tissue sections.

Results

Multivariate statistical analysis of FTIR spectra collected for tissue sections permit an unsupervised method of distinguishing tissue types, and of differentiating between normal and diseased tissue. By analyzing different spectral windows and comparing the results with histology, we found the amide I and II region (1740–1470 cm−1) to be very important in correlating anatomical and histopathological features in tissue to spectral clusters. Since an unsupervised, rather than a diagnostic, algorithm was used in these efforts, no statistical analysis of false-positive/false-negative results is reported at this time.

Conclusions

The combination of FTIR micro-spectroscopy and multivariate spectral processing provides important insights into the fundamental spectral signatures of individual cells and consequently shows potential as a diagnostic tool for cervical cancer.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, Fourier transform infrared micro-spectroscopy, Unsupervised hierarchical clustering

Introduction

Until the early 1990s, cervical cancer was the most frequent neoplastic disease among women in developing countries, before breast cancer became the predominant cancer site [1]. Each year, over 400,000 new cases of invasive cervical cancer are diagnosed world wide, representing nearly 10% of all cancers in women [2]. Currently, screening for cervical disease is carried out via the Papanicolaou (PAP) smear test, in which squamous and glandular epithelial cells are exfoliated with a Cytobrush™ or Ayre spatula from the cervical transformation zone, fixed in ethanol, and stained with the Papanicolou stain. A definitive diagnosis is obtained by cervical biopsy and examination of the stained tissue. The predictive value of a biopsy is higher than that of the PAP test because the anatomical arrangement is preserved allowing evaluation of pathological features in relation to histological architecture.

Cervical disease is classified using the two-tier Bethesda system for PAP smears [3] (low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions, LSIL and HSIL), and the three-tier cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN I, II and III) system for surgical samples. Samples diagnosed as CIN II and CIN III have a higher risk of proceeding to carcinoma in situ (CIS). More recently, the presence of high-risk human papilloma virus (HPV) genotypes has been associated with cervical dysplasia and its progression to cancer [4–6,15]. This is now being used as an adjunct to detect cervical lesions in conjunction with the PAP smear [7–9].

The PAP test has reduced the mortality of invasive cervical cancer by up to 70% [10,11]. Despite its success, cytological screening has limitations, the most important being false-negative results. Reported false-negative rates for the PAP smear vary widely; from as low as 1% to as high as 93% [12–14]. The Consensus Development Conference of Cancer of the Cervix, convened by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), concluded that about half of the false-negative PAP tests are due to inadequate specimen collection, with the other half due to failure of identifying or interpreting the specimens correctly. Alternative techniques, aimed at eliminating subjective diagnoses by cytological screeners, have been pursued. One approach to minimize the error rate in cervical cytology has been to use automated image analysis systems coupled with artificial neural networks (ANNs) to reduce the labor and time necessary to rescreen for false-negatives [16,17]. Another approach has been to improve the quality of slide preparation through the implementation of liquid-based or “thin-prep” methods [18–20]. While automated image analysis systems have fallen out of favor, liquid-based cytological methods have gained a stronger presence in cytology laboratories [21].

The infrared alternative

The previous decade has witnessed the evolution of Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy as an independent modality to discriminate between diseased and normal tissue. Several comprehensive books and articles outline the field [22–25]. One area that has received considerable attention was the application of the FTIR technique to the diagnosis of cervical neoplasia [26–35]. Early studies reported spectral differences between exfoliated cells from patients diagnosed normal and dysplastic by cytological [26,27] and histological methods [28,30]. The essential differences were related to changes in glycogen, nucleic acid, and protein content. Upon further study, it became apparent that the spectral changes observed between normal and diseased samples might not be related to the presence of dysplastic cells per se, but rather to non-specific factors such as localized inflammation effects [31,36], the cell type being measured [32], and the non-specific depletion of cytoplasmic glycogen. These studies demonstrated that a detailed understanding of the spectral features of the cell types, and spectral variations resulting from differentiation, maturation, and cell cycle stages, is a pre-requisite before interpreting the spectral differences between normal and dysplastic cytological diagnosed samples [25]. Other factors that needed to be addressed were the effects of potential confounding variables such as mucin, erythrocytes, leukocytes, and other debris that can obscure diagnostic regions of the spectra [31,36–38]. A study of samples collected at different stages of the menstrual cycle revealed dramatic changes due to variations in glycogen concentration [39].

Since the majority of cervical neoplasia is believed to arise in the transformation zone [40,41], an in-depth spectroscopic investigation into cytological “normal” cells of the cervical transformation zone needed to be carried out. This is best achieved by FTIR mapping or imaging of actual cervical tissue sections obtained by punch biopsies or hysterectomies and comparing the FTIR maps and/or images with the corresponding stained sections.

This report presents preliminary results obtained from the analysis of nearly 750,000 FTIR spectra obtained for cervical biopsy samples. While the aim of this study was to demonstrate that unsupervised multivariate statistical methods can differentiate between tissue types found in cervical biopsies, and distinguish normal from dysplastic and neoplastic tissue areas, this study was not intended to develop a diagnostic algorithm to analyze tissue sections. However, the clusters of spectra produced during this study are being used as input data for the development of a diagnostic algorithm, based on an Artificial Neural Network, to be reported at a later stage.

This report does not “search for distinct cancer markers” to diagnose cancerous areas of a biopsy, but utilizes mathematical procedures, which analyze subtle spectral differences in the entire spectra, to differentiate normal from diseased tissue. Thus, a progression from mild to severe cervical disease will not necessarily be manifested by a progressive change in a spectral parameter. This paper demonstrates, however, that these subtle differences exist, and that normal and diseased areas of tissue can be distinguished spectroscopically.

Since a previous study demonstrated that patient-to-patient variations of spectral patterns are smaller than those encountered between different tissue types and stages of disease [42], a relatively small set of 10 samples was selected for an initial study. The spectral characteristics of normal cervical tissue sections had been reported previously [33]; consequently, the 10 samples reported here were evenly divided between mild and severe dysplasia.

Methodology

Sample preparation

This study was carried out between October and December 2001, under an IRB approval (# 7XM, dated 5/15/2001) from Hunter College. Cervical samples from 10 patients obtained by either cone biopsy or hysterectomy were selected from the cervical tissue data bank at Bellevue Hospital (New York). The samples included five cases originally diagnosed by cytology with HSIL and five with LSIL.

Samples for spectral imaging were prepared as follows. A 4-μm tissue section was cut from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks, mounted on a glass slide, and stained with hematoxylin/eosin (H&E). Up to four adjacent sections (4-μm apart) were re-hydrated and mounted on Ag/SnO2 coated infrared reflective slides (Kevley Technologies) for FTIR mapping. The stained slide is used as a template to identify normal, low-and high-grade dysplastic areas and other interesting anatomical features including inflammation (leukocyte proliferation), erythrocytes, blood vessels, and keratin pearls. For all tissue sections, FTIR maps were collected for glandular and squamous epithelium, and of the cervical transformation zone. Multiple images were recorded on all four adjacent sections. Once the FTIR imaging was completed for all four sections, the IR reflective slide was stained with H&E, and the imaged areas were photographed so that the infrared image could be directly correlated with the morphology. This procedure ascertains that the exact same tissue features are present in the photomicrographs and the IR images.

The stained slides were read by two histopathologists whose comments form the basis of the discussion of each of the pseudo-color maps and photomicrographs. In addition, the original cytological diagnosis (LSIL/HSIL), which was used to select the patients for biopsy, and the original diagnosis of this biopsy, are incorporated in the discussion.

Data acquisition

Spectra were collected with a Bruker IRscope II IR microscope (Bruker Optics Inc., Billerica, MA) equipped with a liquid nitrogen cooled HgCdTe (MCT) detector, and a 36× IR objective. The IRscope II is coupled to a Bruker Vector 22 FTIR spectrometer, controlled by a personal computer (Gateway 2000) incorporating a 200-MHz Pentium processor running under OS/2 Warp. Data collection was carried out using Bruker’s proprietary OPUS (version 3.0) software. The IRScope II and FTIR spectrometer were continually purged with dry air from self-contained air purifiers (Whatman, Inc.).

For FTIR mapping the rectangular aperture was set at 20 × 20 μm2 (accurate to about ±3 μm). These settings provided good signal-to-noise while maintaining excellent spatial resolution. The IR mapping data were collected in reflection mode by scanning the computer-controlled microscope stage in a raster pattern in increments of 10 μm. Interferograms were collected double sided at a resolution of 6 cm−1. At each data point (pixel), eight interferograms were co-added and Fourier transformed using a Happ-Genzel apodization function, and a zero-filling factor of 4.

Data processing/computational procedures

From a biomedical perspective, histopathological diagnosis depends on visualization of the sample morphology. In spectral diagnosis, additional and objective spectroscopic data intrinsic to an area of tissue is collected while maintaining the histopathological information. Thus, spectral data sets contain thousands of individual spectra, where each spectrum consists of wavelength and intensity information and is associated with distinct x and y spatial coordinates. This raw data set is called a spectral “hypercube”, and often contains hundreds of megabytes of data.

Each spectrum in the hypercube provides qualitative and quantitative chemical information. To enable a visual inspection of the chemical information contained in these enormous amounts of data, the individual spectra are converted into a two-dimensional pseudo-color representation. This can be accomplished by uni- or multivariate methods. In univariate analyses, a spectral property for each spectrum (e.g., intensity, integrated intensity, or intensity ratio at two wavelengths) is color coded, and represented as a function of spatial coordinates to yield a two-dimensional pseudo-color map. Different color hues represent different values of the displayed spectral property.

However, the availability of thousands of FTIR spectra in each hypercube also offers the possibility of applying multivariate methods to analyze the data. In multivariate methods, the information of the entire spectrum is used to create a visualization of the data. In this study, we employ an unsupervised clustering approach to investigate cervical tissue. The unsupervised clustering approach is well described in the literature [43–45] and only a brief overview is given below.

In cluster analysis, a matrix is calculated that expresses the similarity, or “distance”, between each spectrum and all other spectra of the data. For two spectra S and R in the data hypercube, this distance is defined as the correlation coefficient CSR according to

| (1) |

Here, the spectra S and R are represented by 1-dimensional vectors of M absorbance values, and S̄ and R̄are the mean values for each vector. The resulting CSR matrix, also known as the covariance matrix, contains N2 entries, where N is the total number of spectra within the data set. However, since the matrix is symmetric, only N(N − 1)/2 spectral distance elements CSR need to be computed.

Subsequently, the two most similar spectra in the hypercube are merged into a “cluster”, and a new distance matrix column is calculated for the new cluster and all existing spectra. The process of merging spectra or clusters into new clusters is repeated, and the CSR is recalculated until all spectra have been combined into a few clusters. This process combines the most similar spectra into the same cluster, while keeping track of which spectra have been incorporated into each cluster. Pseudo-color maps based on cluster analysis are created by assigning a color to each spectral cluster, and displaying this color at the coordinates at which each spectrum was collected. The mean spectra were extracted for all clusters and used for the interpretation of the chemical or biochemical differences between clusters.

The number of clusters was adjusted such that good correspondence with the pathological images was obtained. Reasonable noise in the spectral data does not affect clustering process. In this respect, cluster analysis is much more stable than other methods of multivariate analysis such as principal component analysis (PCA), in which an increasing amount of noise is accumulated in the less relevant clusters. This present study may be viewed as an effort to detect spectral differences by cluster analysis that, subsequently, may be analyzed via ANNs.

Cluster analysis was performed by importing data hypercubes, in Bruker OPUS 3.0 format, into the CytoSpec™ FTIR imaging software package [46]. The maps were processed on a personal computer equipped with a 1.6-GHz Athlon processor and 1.5 GByte of RAM. The first step in the data processing was the removal of pixels with too high or too low absorbance values, or with poor signal/noise ratio from the data set. The remaining spectra are then cut to include only values between 1800 and 800 cm−1, smoothed or derivatized using a Savitsky–Golay algorithm, and base line corrected within this region. All spectra that pass the quality test are subsequently vector normalized between 1800 and 800 cm−1. Chemical (or functional group) maps were created from these spectra by plotting various spectral parameters (e.g., absorbance of the vsym(PO2 −) band intensity, the amide I band at 1653 cm−1, or ratios of integrated intensities) as a function of x–y pixel position.

Unsupervised cluster analysis was performed on three main spectral regions (1800–800, 1740–1570, 1200–1000 cm−1). It took between 15 and 20 min to calculate both the distance and hierarchical cluster matrices, depending on the number of spectra. In most maps, up to 10 clusters were selected corresponding to the major anatomical features. For each cluster map, the mean spectrum for each individual cluster was extracted for comparison with those from different clusters.

After FTIR analysis, the tissue section was stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E). Photomicrographs were recorded of the H&E-stained sections using a digital camera fitted to an Olympus microscope. The digitized photographs were rotated and cropped to size using Microsoft Photo-Editor (2000).

Results

In this study over 90 spectral maps (comprising approximately 750,000 spectra) were recorded from 52 different regions of tissue from 10 different patients. This represents an enormous data bank for multivariate analysis. The data presented below are representative of the 10 samples investigated and show general spectral features that characterize the cervical transformation zone and cervical epithelium highlighting anatomical and histopathological features. Further analysis of these data, including one that utilizes an algorithm trained to recognize tissue abnormalities, will be reported at a later stage.

Normal cervical transformation zone

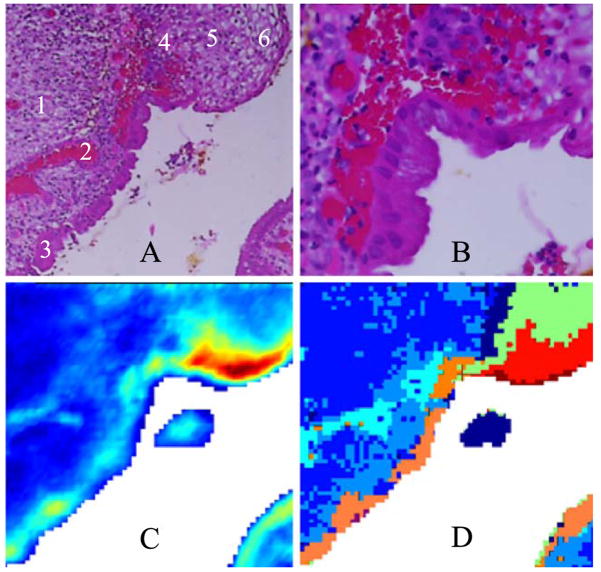

Figs. 1A and 1B show photomicrographs of the transformation zone stained with H&E. The low magnification photomicrograph (1A) shows a 500 × 500 Am area of the ectocervical and endocervical epithelium and the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) along with red blood cells underlying the epithelium. The high magnification photomicrograph in Fig. 1B of the SCJ clearly shows columnar cells, squamous cells, and red blood cells (see figure caption for detail). Fig. 1C shows a spectral map based on univariate analysis by displaying the relative intensity of the 1024-cm−1 band. This band is due to glycogen, but glycoproteins in mucous also contribute at this wave number. The spectra of pure glycogen and glycoproteins were reported in the literature previously [25,33,47,48]. In the 1000- to 1200-cm−1 region, the glycogen spectrum exhibits three prominent peaks at ca. 1151, 1078 and 1028 cm−1. These features are visible as three distinct peaks in the blue traces in Fig. 2E. The squamous region (red) predictably shows high concentration of glycogen whereas the glandular epithelium (bottom left, in light blue/yellow) shows contributions due to glycoproteins.

Fig. 1.

(A) Photomicrograph of a 500 × 500 μm section of cervical tissue (H&E stain). Tissue was stained and photographed after FTIR data acquisition. (1) Connective tissue, (2) blood, (3) glandular epithelium, (4) basal layer of squamous epithelium, (5) intermediate layer, (6) superficial layer. (B) High magnification of the same section showing distinct squamous ectocervical cells, columnar endocervical cells and red blood cells. (C) Univariate map of the tissue section, based on the intensity of the 1024 cm−1 band. Red hues indicate regions of high glycogen concentration, while blue indicates low concentration. (D) 7-cluster map of the tissue section based on the entire 1800–800 cm−1 spectral region.

Fig. 2.

(A) Photomicrograph of a section of cervical squamous epithelium from patient diagnosed with LSIL. The section was stained (H&E) after FTIR data acquisition. (1) Connective tissue, (2) basal layer, (3) parabasal layer, (4) intermediate layer, (5) superficial layer. (B) 9-cluster maps using the entire mid-IR spectral range (1800–800 cm−1). (C) 9-cluster maps using the “protein region” (1740–1470 cm−1). (D) 9-cluster maps using the “glycogen/nucleic acid region” (1200–1000 cm−1). (E) Mean cluster spectra from six of the seven clusters color coded to enable correlation with 2C. Note: the individual colors in panels B–D are assigned by the algorithm for each data set and are not transferable between separate analyses.

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering provides a more useful image because it enables the identification of similar spectral profiles and “clusters” them according to a similarity criterion based on the relative distances of the spectra in multivariate space. This approach yields maps that highlight regions of similar spectra that can be readily compared to anatomical features observed in H&E-stained sections. Fig. 1D depicts a pseudo-color map obtained from unsupervised hierarchical analysis of the 1800–800 cm−1 region. An inspection of Fig. 1D reveals excellent agreement between the cluster demarcations, and the visually observable tissue features, including the superficial layer of squamous epithelium shown in red, the intermediate layer (green) and the basal/parabasal layer (dark blue), as well as columnar cells (orange). The medium blue regions correspond to stromal (connective) tissue, and the light blue areas to red blood cells.

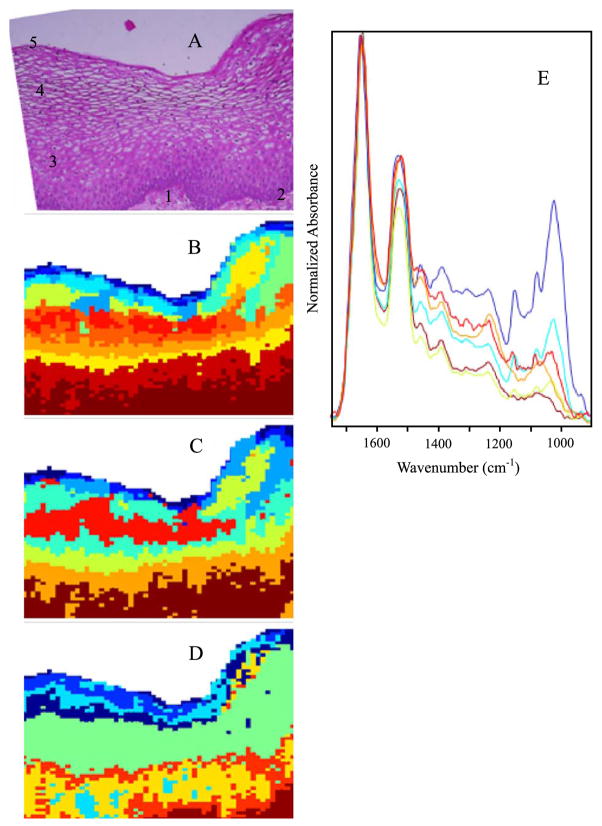

Ectocervical epithelium

Fig. 2 depicts results for cervical squamous epithelium from a patient diagnosed with LSIL. Panel A depicts a photomicrograph of the tissue, stained and imaged after FTIR data acquisition. The different layers of the squamous epithelium can be seen clearly. Panels B–D illustrate the sensitivity toward chemical composition afforded by cluster analysis in different spectral regions, 1800–800 cm−1, 1740–1470 cm−1, and 1200–1000 cm−1. Cluster analysis performed on the 1740–1470 cm−1 spectral range (Panel 2C) results in a demarcation pattern most sensitive in the superficial region of epithelium, where the glycogen content is uniformly high. Thus, most of the differentiation is due to variations in the protein bands. The 1200–1000 cm−1 spectral range (Fig. 2D) loses some differentiation in the superficial/intermediate layer, but is much better in distinguishing the basal/parabasal layers and the stroma. This is an important result since cervical disease frequently originates in the basal layer of the squamous tissue or at the junction of squamous and columnar epithelium. The map based on the entire spectral range (2C) falls in-between the maps shown in Figs. 2B and 2D in discriminatory ability. However, this holds true only for spectral maps based on original intensities; spectral maps based on second derivative spectra exhibit enhanced sensitivity throughout the spectral range (vide infra).

Several distinct regions in the pseudo-color map of Fig. 2D can be directly correlated with the main tissue layers observed in the H&E-stained section. These include the outer superficial layer (various blue hues), the intermediate layer (green), the parabasal and basal layers (orange and yellow), and the connective tissue (brown). In the maps due to the other spectral ranges, various tissue features may be gained or lost.

Fig. 2E shows some of the mean extracted spectra corresponding to map 2C. The mid-blue and light blue traces in Fig. 2E show typical spectral features of a glycogen-rich superficial layer with strong 1151, 1078, and 1028 cm−1 bands due to coupled C–O and C–C stretching and C–O–H deformations motions of glycogen. Previously, we have shown that there exists an excellent correlation between spectral detection of glycogen via these three marker bands, and histologic demonstration of glycogen via periodic acid-Schiff base stain (PAS) [47,48]. The red spectral trace is indicative of the intermediate layer, the green trace represents the parabasal layer, while the brown trace is characteristic of the connective tissue. The green trace shows a dramatic decrease in the glycogen band intensity and a reduction in the amide II/amide I intensity ratio compared to the other mean extracted spectra. The brown trace, correlating to connective tissue, exhibits a broad relative intense feature centered at 1240 cm−1 from strong collagen bands overlapping nucleic acid phosphate groups and virtually no contributions from glycogen in the 1200–1000 cm−1 region. When more clusters are allowed in the computations, other features such as erythrocytes and sites of inflammation can be differentiated from the resultant maps (vide infra).

The discussion of Fig. 2 demonstrated that the computational procedures, using the original spectral intensities and cluster analysis, can be fine-tuned to reveal and emphasize different tissue features. The use of spectral derivatives of the intensity vs. wave number,

| (2) |

further increases the sensitivity of the cluster procedure, and decreases the dependence of the selected wave number range. Derivative spectra emphasize small differences in spectral band shapes, rather than absolute intensities. Thus, small shifts in band positions, and the absence or presence of shoulders, can be readily detected. This is demonstrated in Fig. 3, which depicts the continuation of the same glandular tissue section shown in Fig. 2, adjacent to the right of Fig. 2A.

Fig. 3.

(A) Photomicrograph of a section of cervical squamous epithelium from patient diagnosed with LSIL. This section is the continuation, to the right, of the one shown in Fig. 2A, and was stained (H&E) after FTIR data acquisition. (B) 9-cluster map, constructed from the second derivative spectra and the entire mid-IR spectral range (1800–800 cm−1).

The cluster map shown in Fig. 3A shows in exquisite detail the different tissue layers, including stroma, basal layer, and the maturation of cells within the parabasal, intermediate and superficial layers. (Note that the colors in Figs. 2 and 3 are not consistent, and may denote different tissue types). Although the spectral differences in the superficial layer are closely associated with increasing glycogen concentration, three areas shown in orange in the top layer correspond to low glycogen content. These areas are found within the thickened parabasal/superficial layer, and may be indications of early stages of parakeratosis (a deposit of keratin in the epithelium). Most interesting is the occurrence of the clusters shown in red in the thickened epithelium. These red clusters correspond to areas of inflammatory response below the keratin deposits. Thus, the spectral methods detect changes in the tissue layers below the parakeratosis.

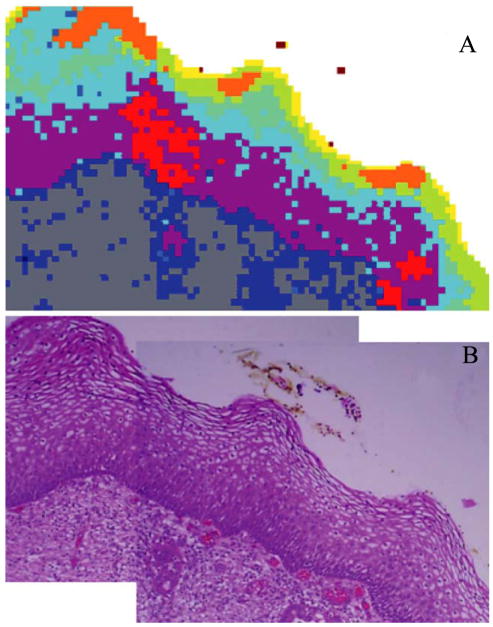

Fig. 4 shows a tissue section from a patient whose PAP diagnosis was HSIL. The tissue diagnosis was CIN II/CIN III. This figure demonstrates clearly that the differentiation of tissue types is due to spectral changes that can be visualized and interpreted, and not due to random noise or other confounding factors. The blue traces (2nd derivative spectra) shown in Panel 4C were selected from the light blue areas on the left side of Panel 4B, whereas the red traces in 4C were from the light and dark red sections of the diseased areas. The obvious spectral differences (band shifts and intensity variations) cause the differentiation into clusters. Fig. 4C also demonstrates why spectral mapping is possible using different spectral windows. The red and blue traces in Panel 4C exhibit concomitant changes in the amide I/amide II band region (1800–1450 cm−1) and the low frequency window between 1200 and 900 cm−1. Since all layers of this tissue were found to be glycogen-free, we may assume that the spectral differences in the low-frequency window are mostly due to vibrations of the phosphate ( ) groups of DNA and RNA.

Fig. 4.

(A) Photomicrograph of glandular epithelium from a patient diagnosed with HSIL, stained (H&E) after FTIR data acquisition. The dark-staining areas are associated with CIN II/CIN III. (B) 9-cluster map, constructed from the second derivative spectra and the entire mid-IR spectral range (1800–800 cm−1). (C) Individual 2nd derivative spectra collected from regions indicated by the ellipses in B. See text for detail.

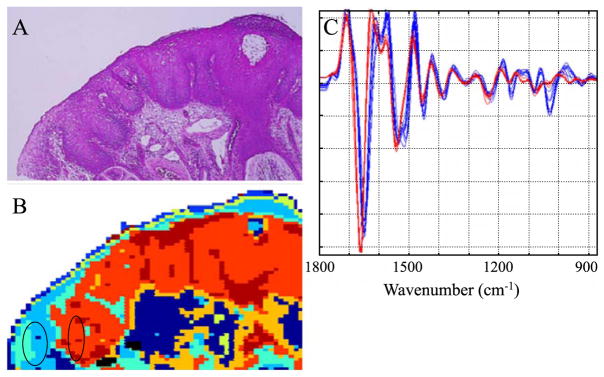

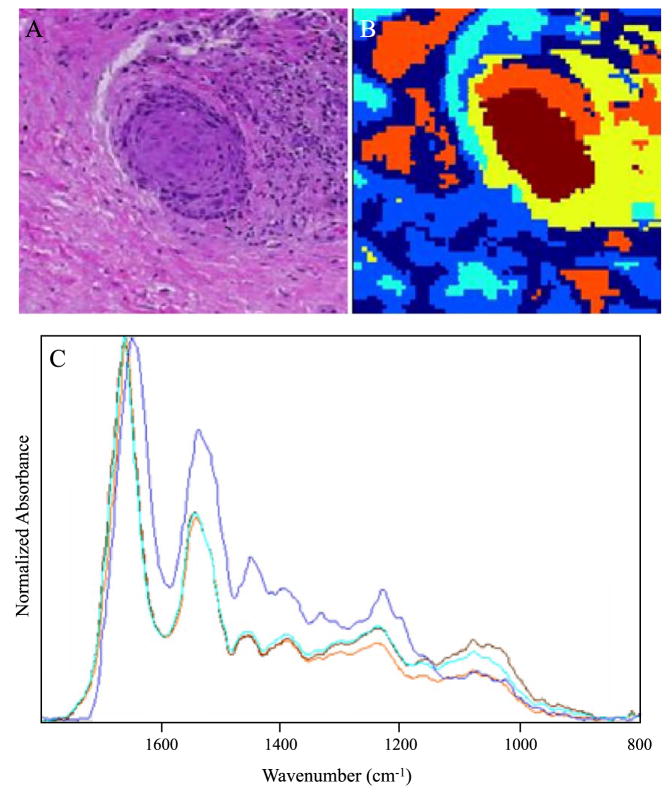

Fig. 5 depicts results from a section of connective tissue from a patient whose PAP results indicated HSIL. Fig. 5A shows a photomicrograph of a small metastasis adjacent to a large area of diseased glandular epithelium (not shown). Fig. 5B depicts the corresponding pseudo–color map, and Fig. 5C shows the extracted mean cluster spectra. The abnormal region of the micro-metastasis appears brown and orange in the cluster map. The light blue cluster highlights a region with many abnormal cells with irregular shaped nuclei varying considerably in size along with some leukocytes. The mid-blue and dark blue colors are indicative of different types of connective tissue. The yellow highlights a region of erythrocytes and lymphocytes in the sample. The spectra representative of the metastasis (brown) exhibit a significant decrease in the amide II/amide I intensity ratio compared to the surrounding tissue matrix. This is indeed interesting and confirms the results of an earlier study [28] investigating FTIR spectra of exfoliated cervical cells with principal components analysis (PCA). In that study, the amide II vibration was identified as an important loading variable to distinguish normal from diseased tissue.

Fig. 5.

(A) Photomicrograph of a metastatic inclusion within the tissue matrix form a patient diagnosed with HSIL, stained (H&E) after FTIR data acquisition. (B) Cluster map of the metastatic inclusion. (C) Mean extracted spectra from the cluster map presented in B.

Other features characteristic of this spectrum include the pronounced symmetric and asymmetric phosphodiester vibrations at 1244 and 1080 cm−1, respectively. This is in agreement with earlier studies [26,27,30] on exfoliated cervical cells, which correlated abnormality with an observed increase in the intensity of phosphodiester vibrations. In general, these bands appear more intense than the methyl and methylene deformation modes (1450–1350 cm−1) in areas of high-grade dysplasia in all samples investigated in this study. The light blue spectrum is representative of abnormal cells and leukocytes adjacent to the metastasis and is very similar to the spectrum of the metastasis in terms of the amide II/amide I ratio and the relative intensity of the phosphodiester bands. This spectrum does differ slightly from the metastasis spectrum in the 1100–1000 cm−1 region, the latter showing a more intense symmetric phosphodiester band at 1080 cm−1. The two clusters corresponding to connective tissue (mid blue and dark blue) are significantly different in terms of the amide II/amide I ratio and the intensity of the methyl and methylene deformation modes (approximately 1400 cm−1) but similar in the phosphodiester region (1200–1000 cm−1).

Discussion

The pursuit of an FTIR-based screening test for cervical dysplasia has been marred by the inherent heterogeneity of exfoliated sample specimens [31,36]. Hitherto, studies to methodically assess this variability have been limited to investigating cultured cell lines [49] or cells that can be isolated from peripheral blood [36]. The combination of FTIR microscopy with multivariate image processing provides a direct method to assess biological variability and thereby add to the discriminating power of any diagnostic algorithm. Because the spectral changes are analyzed by unsupervised multivariate methods, the approach represents a “blind” test of the methodology. Moreover, by directly correlating the spectral maps with the anatomical and histopathological features, the approach is intrinsically validated.

Central to the success of this approach has been the incorporation of Ag/SnO2-coated microscope slides. The slides have several advantages over more conventional infrared substrates such as calcium or barium fluoride, or zinc selenide. These include the low cost of the slides (US$ 1, as compared to approximately hundred dollars for some of the other substrates) and their suitability for routine analysis. Samples on these slides can be inspected microscopically by a cytologist or pathologist without interference from the coating. Furthermore, the resulting spectra do not require any mathematical transformation to remove the specular reflection component inherent in conventional FTIR reflection spectroscopy.

Consequently, a large spectral database could be constructed at low cost, and excellent histopathological correlation was possible. The large database generated permitted a multivariate statistical approach to the data analysis, which resulted in important insights into the spectroscopy of the different tissue types encountered in the histopathological analysis of cervical tissue. By analyzing different spectral regions, it became evident that the correlation between anatomical features observed in stained tissue and the principal demarcations in the cluster maps could be achieved in two separate spectral windows. Since we adopted a vector normalization approach for this study, we negated the dependence on amide I normalization. Consequently, we were able to use the protein amide I and II band features for cluster analysis. The differentiation of tissue types is based on variations of band positions, intensities, and half-widths in the amide II/amide I manifolds. Such differences may indicate changes in protein abundance of the individual cell types, as well as changes in protein secondary structure. The dependence on the amide I and II bands for classification is not surprising given the high protein content of cells (approximately 60% of total dry mass) and the sensitivity of the infrared technique to protein concentration and secondary structure.

The variations in intensity of the asymmetric and symmetric phosphate stretching vibrations in the low-frequency (1200–1000 cm−1) window, coupled with changes in the glycogen concentration, result in a good correlation with anatomical and histopathological features as well, in particular, if second derivative spectra are used. Most of the variation is detected in the superficial layers where the glycogen concentration dramatically decreases approaching the intermediate layer. It is now well established that the variation in glycogen concentration in cervical-exfoliated cells and tissues renders this region almost useless for diagnostic purposes [25,39].

The mean cluster spectra extracted for different patients from regions with comparable histopathology are quite similar. This confirms the results by Lasch et al. [44] who reported patient-to-patient variations smaller than those due to different tissue types and pathological diagnoses. The spectra from areas of CIN had several characteristic features including pronounced symmetric and asymmetric phosphate bands at 1078 and 1240 cm−1, a significant reduction in glycogen band intensity and a relatively small amide II/amide I ratio. These spectra were similar to spectra extracted from clusters that correlated well with leukocyte proliferation observed in the stained tissue. Although leukocyte spectra are difficult to discern from CIN spectra by eye, the unsupervised hierarchical clustering approach can easily identify each type by subtle differences in the amide I and II modes. Consequently, a multivariate approach is the best way to distinguish tissue types and to detect disease cervical tissue.

This paper demonstrates the clear potential of FTIR absorption/reflection microscopy and unsupervised hierarchical clustering in the analysis of cervical tissue samples. A significant development in the methodology is the application of Ag/SnO2-coated IR reflective slides, which enable both infrared analysis and light microscopic inspection of the same stained samples. A data bank of all the important cell signatures was retained from samples that were directly re-assessed by pathologists and cytologists to obtain a gold standard for comparison and validation. The results reveal several insights into the spectroscopy of cervical cells, in particular, they point to the importance of the amide bands in cell identification and cytopathology. We plan to continue this study using the mean extracted spectra as inputs to train an ANN to identify various anatomical and histopathological features in cervical tissue.

Acknowledgments

Partial support of this research through grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA 81675 and GM 60654 to MD) is gratefully acknowledged. A “Research Centers in Minority Institutions” award RR-03037 from the National Center for Research Resources of the NIH, which supports the infrastructure of the Chemistry Department at Hunter, is also acknowledged. This work was also supported by a Commonwealth National Health and Medical Research Council Grant (Application Number-236812).

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of 25 major cancers in 1990. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1999;80:827–41. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990315)80:6<827::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campaign CR Cancer of the cervix uteri. Commonwealth research centre; 1995. Fact sheet 12

- 3.Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriary A, O’Connor D, Prey M, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System—Terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287:2114–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiffman MH, Bauer HM, Hoover RN, Glass AG, Cadell DM, Rush BB, et al. Epidemiologic evidence showing that human papilloma virus infection causes most cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:958–64. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.12.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furumoto H, Irahara M. Human papilloma virus (HPV) and cervical cancer. J Invest Med. 2002;49:124–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manos MM, Kinney WK, Hurley LB, Sherman ME, Shieh-Ngai J, Kurman RJ, et al. Identifying women with cervical neoplasia-Using human papillomavirus DNA testing for equivocal Papanicolaou results. JAMA. 1999;281:1605–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.17.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zielinski GD, Snijders PJF, Rozendaal L, Voorhorst FJ, van der Linden HC, Runsink AP, et al. HPV presence precedes abnormal cytology in women developing cervical cancer and signals false negative smears. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:398–404. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elfgren K, Jacobs M, Walboomers JMM, Meijer CJLM. Rate of human papillomavirus clearance after treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:965–71. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaarenstroom KN, Melkert P, Walboomers JMM, Van Den Brule AJC, Van Bommel PFJ, Meyer CJLM, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA and genotypes: prognostic factors for the progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1994;4:73–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.1994.04020073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams GH, Romanowski P, Morris L, Madine M, Mills AD, Stoeber K, et al. Improved cervical smear assessment using antibodies against proteins that regulate DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14932–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larson NS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gay JD, Donaldson LD, Goellner JR. False-negative results in cervical cytologic studies. Acta Cytol. 1985;29:1043–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiBonito L, Falconieri G, Tomasic G, Colautti I, Bonifacio D, Dudine S. Cervical cytopathology. Cancer. 1993;72:3002–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931115)72:10<3002::aid-cncr2820721023>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MMWR. Regulatory closure of cervical cytology laboratories: recommendations for a public health response. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1997. (December 19), [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franco EL, Duarte-Franco E, Ferenczy A. Cervical cancer: epidemiology, prevention and the role of human papilloma virus infection. Can Med Assoc J. 2001;164:1017–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fetterman BJ, Pawlick GF, Koo H, Hartinger JS, Gilbert C, Connell S. Determining the utility and effectiveness of the NeoPath AutoPap 300 QC system used routinely. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:13–21. doi: 10.1159/000330862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mango LJ, Valente PT. Neural Network-assisted analysis and microscopic re-screening in presumed negative cervical cytologic smears. Acta Cytol. 1998;42:227–32. doi: 10.1159/000331551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilbur DC. Location-guided screening of liquid-based cervical cytology specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:399–407. doi: 10.1309/7LRF-DU8Q-8H1W-N7T4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker JJ. Conventional and liquid-based cervico-vaginal cytology: a comparison with clinical and histologic follow-up. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:185–8. doi: 10.1002/dc.10158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ring M, Bolger N, O’Donnell M, Malkin A, Bermingham N, Akpan E, et al. Evaluation of liquid-based cytology in cervical screening of high-risk populations: a split study of colposcopy and genito-urinary medicine populations. Cytopathology. 2002;13:152–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.2002.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartmann KE, Nanda K, Hall S, Myers E. Technologic advances for evaluation of cervical cytology: is newer better? Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2001;56:765–74. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200112000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mantsch HH, Chapman D. Infrared spectroscopy of biomolecules. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wetzel DL, LeVine SM. Biological applications of infrared micro-spectroscopy. In: Gremlich HU, Yan B, editors. Biological applications of infrared micro-spectroscopy. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2001. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaw RA, Mansfield JR, Rempel SP, Low-Ying S, Kupriyanov VV. Analysis of biomedical spectra and images: from data to diagnosis. J Mol Struct (Theochem) 2000;500:129–38. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diem M, Boydston-White S, Chiriboga L. Infrared spectroscopy of cells and tissues: shining light onto a novel subject. Appl Spectrosc. 1999;53:148A–61A. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong PTT, Wong RK, Caputo TA, Godwin TA, Rigas B. Infrared spectroscopy of exfoliated human cervical cells: evidence of extensive structural changes during carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1088–10992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.10988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong PTT, Wong RK, Fung MFK. Pressure tuning FT-IR study of human cervical tissues. Appl Spectrosc. 1993;47:1058–63. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wood BR, Quinn MA, Burden FR, McNaughton D. An investigation into FTIR spectroscopy as a biodiagnostic tool for cervical cancer. Biospectroscopy. 1996;2:143–53. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood BR, Quinn MQ, Tait B, Romeo M, Mantsch HH. A FTIR spectroscopic study to identify potential confounding variables and cell types in screening for cervical malignancies. Biospectroscopy. 1998;4:75–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6343(1998)4:2%3C75::AID-BSPY1%3E3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fung MFK, Senterman M, Eid P, Faught W, Mikael NZ, Wong PTT. Comparison of Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopic screening of exfoliated cervical cells with standard Papanicolou screening. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;66:15–9. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiriboga L, Xie P, Vigorita V, Zarou D, Zakim D, Diem M. Infrared spectroscopy of human tissue: II. A comparative study of spectra of biopsies of cervical squamous epithelium and of exfoliated cervical cells. Biospectroscopy. 1997;4:55–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6343(1998)4:1%3C55::AID-BSPY6%3E3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiriboga L, Xie P, Yee H, Vigorita V, Zarou D, Zakim D, et al. Infrared spectroscopy of human tissue: I. Differentiation and maturation of epithelial cells in the human cervix. Biospectroscopy. 1998;4:47–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6343(1998)4:1%3C47::AID-BSPY5%3E3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiriboga L, Xie P, Yee H, Zarou D, Zakim D, Diem M. Infrared spectroscopy of human cells and tissues: IV. Detection of dysplastic and neoplastic changes in human cervical tissue via infrared microscopy. Cell Mol Biol. 1998;44:219–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohenford MA, Godwin TA, Cahn F, Bhandare P, Caputo TA, Rigas B. Infrared spectroscopy of normal and abnormal cervical smears: evaluation by principal component analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;66:59–65. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohenford MA, Rigas B. Cytologically normal cells from neoplastic cervical samples display extensive structural abnormalities on IR spectroscopy: implications for tumor biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15327–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood BR, Quinn MA, Tait B, Hislop T, Romeo M. FTIR micro-spectroscopic study of cell types and potential confounding cells in screening for cervical malignancies. Biospectroscopy. 1998;4:75–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6343(1998)4:2%3C75::AID-BSPY1%3E3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romeo M, Burden FR, Wood BR, Quinn MA, Tait B, McNaughton D. Infrared micro-spectroscopy and artificial neural networks in the diagnosis of cervical cancer. Cell Mol Biol. 1998;44:179–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romeo M, Wood BR, Quinn MA, McNaughton D. The removal of blood components from cervical smears: implications for cancer diagnosis using FTIR spectroscopy. Vibr Spectrosc. 2002;28:167–75. doi: 10.1002/bip.10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romeo M, Wood BR, McNaughton D. Observing the cyclical changes in cervical epithelium using infrared micro-spectroscopy. Vibr Spectrosc. 2002;28:167–75. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ostor AG. Studies on 200 cases of early squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993;12:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ostor AG, Mulvany N. The pathology of cervical neoplasia. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1996;8:69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lasch P, Naumann D. FT-IR micro-spectroscopic imaging of human carcinoma thin sections based on pattern recognition techniques. Cell Mol Biol. 1998;44:189–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mansfield JR, McIntosh LM, Crowson AN, Mantsch HH, Jackson M. Appl Spectrosc. 1999;53:1323–30. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lasch P, Haensch W, Lewis EN, Kidder LH, Naumann D. Characterization of colorectal adenocarcinoma by spatially resolved FT-IR micro-spectroscopy. Appl Spectrosc. 2002;56:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diem M, Chiriboga L, Yee H. Infrared spectroscopy of human cells and tissue: VIII. Strategies for analysis of infrared tissue mapping data and applications to liver tissue. Biopolymers (Biospectroscopy) 2000;57:282–90. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2000)57:5<282::AID-BIP50>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lasch P. A Matlab based application for infrared imaging. see http://www.cytospec.com for details.

- 47.Chiriboga L, Yee H, Diem M. Infrared spectroscopy of human cells and tissue. Part VI: a comparative study of histopathology and infrared micro-spectroscopy of normal, cirrhotic, and cancerous liver tissue. Appl Spectrosc. 2000;54:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chiriboga L, Yee H, Diem M. Infrared spectroscopy of human cells and tissue. Part VII: FT-IR microscopy of DNAase- and RNAase-treated normal, cirrhotic, and neoplastic liver tissue. Appl Spectrosc. 2000;54:480–5. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boydston-White S, Gopen T, Houser S, Bargonetti J, Diem M. Infrared spectroscopy of human tissue: V. IR spectroscopic studies of myoeloid leukemia (ML-1) cells at different phases of the cell cycle. Biospectroscopy. 1999;5:219–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6343(1999)5:4<219::AID-BSPY2>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]