Abstract

After an outbreak in 2000 of eosinophilic meningitis in tourists to Jamaica, we looked for Angiostrongylus cantonensis in rats and snails on the island. Overall, 22% (24/109) of rats harbored adult worms, and 8% (4/48) of snails harbored A. cantonensis larvae. This report is the first of enzootic A. cantonensis infection in Jamaica, providing evidence that this parasite is likely to cause human cases of eosinophilic meningitis.

Key words: Angiostrongylus cantonensis, rats, snails, Jamaica

Angiostrongylus cantonensis is the most common infectious cause of eosinophilic meningitis worldwide (1). Although human infections with A. cantonensis are traditionally associated with Southeast Asia and the Pacific Basin, sporadic cases have been reported in several countries outside this region (1,2). In the Caribbean, eosinophilic meningitis has not been commonly reported, although A. cantonensis has been found in rats from Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic (3–5).

A case of eosinophilic meningitis was described in 1994 in an adult Jamaican who had never traveled outside the country (6,7). In the absence of confirmatory histology or serology, the question of the endemicity of A. cantonensis in Jamaica at that time was raised (6,7). In May 2000, 12 persons in a group of 23 U.S. tourists who visited Jamaica for a week met the clinical definition for eosinophilic meningitis within 6-30 days (median 11) of returning home. Nine persons required hospitalization; there were no deaths. There was serologic evidence of exposure to A. cantonensis in eight persons who had eaten salad at the same restaurant, a common exposure that might account for all cases.

Since A. cantonensis has not been documented in Jamaica and many restaurants in Jamaica’s tourist areas serve imported vegetables, the source of contamination of the vegetables was not necessarily on the island. We investigated whether A. cantonensis occurs naturally in the wild rat and snail populations of Jamaica.

The Ministry of Health collected 109 rats through the rat control program run by the Public Health Department. Rats were collected in eight sites across the island (Table) and sent to the Parasitology Research Laboratories at the University of the West Indies, where the cardiopulmonary system was dissected to determine infection status. In addition, staff from University of the West Indies and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collected snails from four sites (Table) and examined them for infection.

Table. Recovery of Angiostrongylus cantonensis from rats and snails, Jamaica, 2000.

| Location | Host | No. infected/no. examined (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Rats | ||

| Freeport | Rattus norvegicus R.rattus | 6/10 (60) 0/0 |

| Mandeville | R. norvegicus R. rattus | 10/17 (59) 0/0 |

| Black River | R. norvegicus R.rattus | 2/11 (18) 1/4 (25) |

| Kingston | R. norvegicus R.rattus | 1/12 (8) 1/11 (9) |

| Lucea | R. norvegicus R.rattus | 1/15 (7) 0/0 |

| Montego Bay | R. norvegicus R.rattus | 0/0 1/12 (8) |

| Port Antonio | R. norvegicus R.rattus | 0/8 0/3 |

| Lime Hall | R. norvegicus R.rattus | 0/1 1/1 (100) |

| Snails | ||

| Mandeville | Thelidomus asper | 4/10 (40) |

| Brown’s Town | Orthalicus jamaicensis Dentellaria sloaneana | 0/27 0/2 |

| Yallahs | Orthalicus jamaicensis | 0/6 |

| Scott’s Pass | Orthalicus jamaicensis | 0/3 |

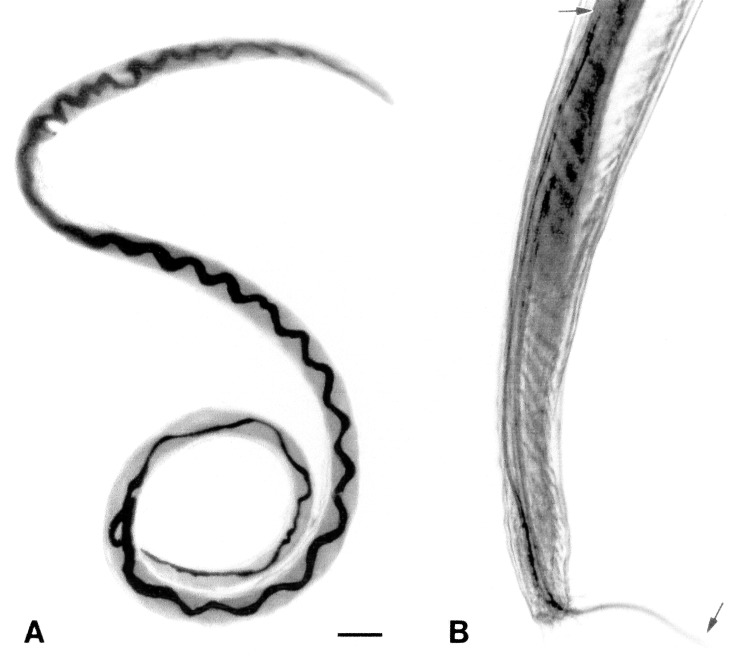

Adult worms were recovered from the cardiopulmonary systems of 24 rats (20/78 Rattus norvegicus; 4/31 R. rattus) (Table). These worms had features characteristic of Angiostrongylus, including size (males measured 14-15 mm in length; females 24-26 mm in length), body shape, and prominent dark intestine (Figure 1A). The long copulatory spicules in the male worms, which measured approximately 1.2 mm (Figure 1B), are diagnostic for A. cantonensis, as the spicules of other species in the genus are generally <0.5 mm long (8).

Figure 1.

Adult Angiostrongylus cantonensis recovered from rat lungs. A. Adult female worm with characteristic barber-pole appearance (anterior end of worm is to the top). Scale bar = 1 mm. B. Tail of adult male, showing copulatory bursa and long spicules (arrows). Scale bar = 85 μm.

Overall, 22% of the rats were infected with A. cantonensis. Infection rates did not differ significantly between R. rattus and R. norvegicus (chi square 2.10; p=0.148). The mean number of worms recovered per infected rat was 17±3.5 (range 3-27).

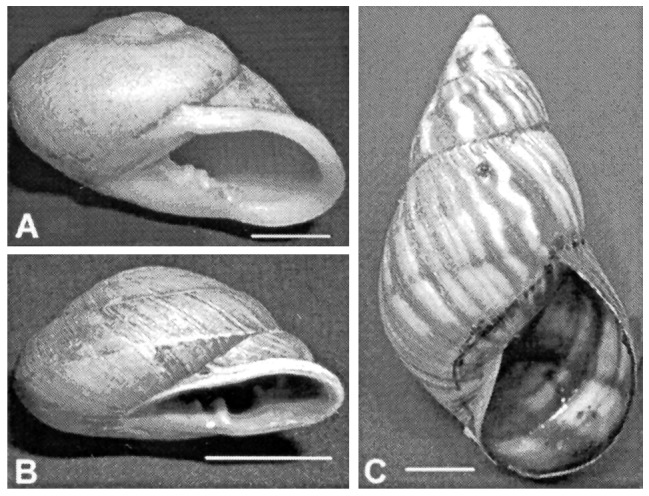

Land snails (Figure 2) were collected by hand from small farms and residential gardens and sent to the Division of Parasitic Diseases laboratory, CDC, Atlanta. A portion of the muscular head-foot region was excised from each surviving snail, cut into smaller fragments, and placed in separate dishes containing digestion fluid (0.01% pepsin in 0.7% v/v aqueous HCl [9]). Dishes were examined for nematode larvae at 4-5 hours and 24 hours after digestion.

Figure 2.

Three species of land snails collected in Jamaica and examined for Angiostrongylus larvae. A. Thelidomus asper. B. Orthalicus jamaicensis. C. Dentellaria sloaneana. Scale bar = 1 cm.

Four of 10 Thelidomus asper collected in Mandeville were found positive for A. cantonensis larvae, but neither Orthalicus jamaicensis (n=36) nor Dentellaria sloaneana (n=2) were infected (Table). Living larvae digested from Thelidomus were easily recognized and recovered because they retained motility in the digestion fluid. Larvae were examined microscopically, and the morphologic features compared with those in published reports (10) and reference A. cantonensis larvae to confirm identification. Two species of lungworm (metastrongyles) larvae were recovered. Most larvae were Angiostrongylus cantonensis (375 to 420 [mean 402] µm in length after fixation in hot alcohol), but a small number of Aelurostrongylus abstrusus (400 to 440 [mean 427] µm in length after fixation in hot alcohol), a lungworm of cats, were also observed. Typical of lungworm larvae, the two species were similar in size and the presence of characteristic sclerotized rhabdions at the anterior end of the larvae. The larvae were easily distinguished, however, by the shape of the tip of the tail; A. cantonensis had a constriction near the end of the tail and ended in a fine point, while A. abstrusus terminated in a knob (10,11).

This is the first report of enzootic A. cantonensis infection in Jamaican rats and snails; our data show that the range of the parasite extends to another Caribbean country outside Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico (3–5). The occurrence of the parasite at high rates in rats and in specific groups of snails, earlier findings of eosinophilic meningitis in a resident, and the recent outbreak of A. cantonensis-associated eosinophilic meningitis in visitors to the island suggest that autochthonous transmission to humans is probable in Jamaica. These studies are being extended to determine the full distribution of the parasite and the species of snails involved in its transmission. Furthermore, serologic tests need to be developed to confirm infections in persons in the Caribbean.

Public health officials, clinical parasitologists, and travel medicine practitioners should consider A. cantonensis as a causative agent of eosinophilic meningitis in Jamaican residents and travelers to the island.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Smikle, H. McDaniel, C. McLean, P.N. Levett, Laura Redmond, Adriana Lopez, and the staff of the Jamaican Ministry of Health for their contributions to the study. We also thank Lawrence Ash, who kindly provided preserved A. cantonensis larvae for morphologic comparison with larvae collected in Jamaica.

Biography

Dr. Lindo is a senior lecturer in the Department of Microbiology at the University of the West Indies and consultant parasitologist to the University Hospital of the West Indies in Kingston, Jamaica. His primary research interest is the epidemiology of helminth infections.

Footnotes

Suggested citation: Lindo JF, Waugh C,* Hall J, Cunningham-Myrie C, Ashley D, Eberhard ML, et al. Enzootic Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Rats and Snails after an Outbreak of Human. Emerg Infect Dis. [serial on the Internet]. 2002 Mar [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol8no3/01-0316.htm

References

- 1.Kliks MM, Palumbo NE. Eosinophilic meningitis beyond the Pacific Basin: the global dispersal of a peridomestic zoonosis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the nematode lungworm of rats. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:199–212. 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90097-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.New D, Little MD, Cross J. Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection from eating raw snails. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1105–6. 10.1056/NEJM199504203321619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aguair PH, Morera P, Pasqual J. First record of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Cuba. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30:963–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen E, Gubler DJ, Sorensen K, Beddard J, Ash LR. First report of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Puerto Rico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985;35:319–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vargas M, Gomes Perez JD, Malek EA. First record of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in the Dominican Republic. Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;43:253–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrow KO, St Rose A, Lindo JF. Eosinophilic meningitis: Is Angiostrongylus cantonensis endemic in Jamaica? West Indian Med J. 1996;45:70–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slom TJ, Cortese MM, Gerber SI, Jones RC, Holtz TH, Lopez AS, et al. An outbreak of eosinophilic meningitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis in travelers returning from the Caribbean. N Engl J Med. 2002. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhaibulaya M. Morphology and taxonomy of major Angiostrongylus species of Eastern Asia and Australia. In: Cross JH, editor. Studies on Angiostrongylus in Eastern Asia and Australia. Taipei, Taiwan: US Naval Medical Research Unit #2, 1979. p. 4-13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graeff-Teixeira C, Morera P. Metodo de digestao de moluscos em acido cloridrico para isolamento de larvas de metastrongilideos. Biociencias, Porto Alegre. 1995;3:85–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ash LR. Diagnostic morphology of the third-stage larvae of Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Angiostrongylus vasorum, Aelurostrongylus abstrusus, and Anafilaroides rostratus (Nematoda: Metastrongyloidea). J Parasitol. 1970;56:249. 10.2307/3277651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhaibulaya M. Comparative studies on the life history of Angiostrongylus mackerrasae Bhaibulaya, 1968 and Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Chen, 1935). Int J Parasitol. 1975;5:7–20. 10.1016/0020-7519(75)90091-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]