Abstract

Objective

To compare the relation between mortality and income inequality in Canada with that in the United States.

Design

The degree of income inequality, defined as the percentage of total household income received by the less well off 50% of households, was calculated and these measures were examined in relation to all cause mortality, grouped by and adjusted for age.

Setting

The 10 Canadian provinces, the 50 US states, and 53 Canadian and 282 US metropolitan areas.

Results

Canadian provinces and metropolitan areas generally had both lower income inequality and lower mortality than US states and metropolitan areas. In age grouped regression models that combined Canadian and US metropolitan areas, income inequality was a significant explanatory variable for all age groupings except for elderly people. The effect was largest for working age populations, in which a hypothetical 1% increase in the share of income to the poorer half of households would reduce mortality by 21 deaths per 100 000. Within Canada, however, income inequality was not significantly associated with mortality.

Conclusions

Canada seems to counter the increasingly noted association at the societal level between income inequality and mortality. The lack of a significant association between income inequality and mortality in Canada may indicate that the effects of income inequality on health are not automatic and may be blunted by the different ways in which social and economic resources are distributed in Canada and in the United States.

Introduction

A large body of research reports an association between income distribution and health1–14 and a range of hypotheses articulates possible mechanisms operating between income inequality and poor health outcomes.15,16 Among American states, mortality is more weakly correlated with mean or median state income than it is with various measures of how that income is shared within a state.5,6 US metropolitan areas with greater income inequality also have significantly higher mortality than metropolitan areas with more equal income distributions, independent of the median income of the metropolitan area.8

Collectively these studies point to the conclusion that populations in areas where there is an unequal income distribution have higher mortality than populations in more homogeneous areas. While some have claimed that the relation between income inequality and mortality is an artefact of the non-linear relation between income and mortality at the individual level,17 Wolfson and colleagues18 and others reporting findings from multilevel analyses19–22 provide substantial evidence for a non-artefactual explanation.

We compared income inequality and age grouped mortality in Canada and the United States. We considered two levels of geographic aggregation: state/provincial and metropolitan area. The comparison of states/provinces and US metropolitan areas is compelling in that it has the potential to highlight characteristics and policies specific to particular social contexts that could affect health. While the product of similar economic, social, and cultural forces,23 Canada and the United States also have some major differences, especially with regard to social policy and racial divisions. US metropolitan areas differ greatly from Canadian metropolitan areas in terms of the degree of economic and social inequality they generate and the ways in which unequal material circumstances and social relations are institutionalised through policy and urban political structure.24,25 While economic segregation and social polarisation are less pronounced in Canadian cities, some studies have suggested that they increased in the last decade of the 20th century.26,27

Incomes at the bottom of the distribution are higher in Canada than in the United States, and while inequality in net income rose between 1985 and 1995 in the United States it actually fell slightly in Canada because of the redistributive effects of Canadian taxation and transfer policies.28 Furthermore, since the 1980s, pay inequality in Canada has widened much less than in the United States.28,29 In the United States, labour market prospects for low skilled workers have been poor over the past two decades. Hypotheses such as the growing skill requirements of a global economy, deindustrialisation, relocations of employers to suburban areas, and racial discrimination have been offered to explain these trends.30

Methods

Associations between income inequality and mortality were studied in the 50 US states and the 10 Canadian provinces, as well as in 282 US and 53 Canadian metropolitan areas with populations greater than 50 000 (as of 1990 in the United States and 1991 in Canada). All mortalities were age standardised to the Canadian population in 1991. The associations were examined separately by the following age and sex groupings for the states and provinces: infants (less than 1 year), children and youth (1 to 24 years), working age men (25 to 64 years), working age women (25 to 64 years), elderly men (65 years and older), and elderly women (65 years and older). Age groupings were the same for metropolitan areas but breakdowns by sex were unavailable.

Inequality was operationalised as the proportion of total household income accruing to the less well off 50% of households within an area (that is, the “median share” of income). In a setting of perfect equality, the bottom half of the income distribution receives 50% of the total income and the area then has a median share value of 0.50. The indicator has recently been used in similar studies on inequality and mortality,5,8 and thus allowed for comparability of results. Moreover, tests with a range of other measures of inequality and polarisation suggested that this choice did not substantially affect the results.

US data

Mortality data for the 50 US states came from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Wonder website. Mortalities by state, sex, and age were averaged over three years (1989-91) to improve the stability of the estimates. State median share proportions and the median income values were generated from the 1990 US census and have appeared in a previous paper by Kaplan and colleagues.5 Metropolitan area mortalities and median share proportions were from the work of Lynch and colleagues.8

Canadian data

The income inequality data for Canada came from a micro data file of the 1991 census of Canada. The income definition used in the Canadian calculations, like that for the United States, included income from wages and salaries, net income from self employment, government transfers, and investment income. Canadian mortality data were based on three year averages (1990-2) by province, sex and age group, and by metropolitan area and age group.

Model building and general linear testing

Multiple regression analyses were conducted only on the metropolitan area data because of the small number of Canadian provinces. Given that the reliability of the estimated mortality is related to the populations of metropolitan areas we used weighted regression with population size as the weight. Use of these weights ensures that the regression line goes through the mean mortality of the entire population under study. Furthermore, the use of such a weighted regression allows for the unobserved differences in mortality between Canada and the United States, potentially because of differences in social structure, to be taken into account through the use of a dummy variable.31

The regression analyses proceeded in four steps. Firstly, models specific for age group were fitted for the 282 US metropolitan areas with median share of total metropolitan area household income as an explanatory variable. Secondly, median income for the US metropolitan areas was added as an explanatory variable. Thirdly, the 53 Canadian metropolitan areas were added. In the combined models, metropolitan median household income for the Canadian cities was adjusted downwards by a factor of 0.8 (this is Statistics Canada's purchasing power parity rate, applied to personal final expenditure, for 199523) to achieve purchasing power parity between the two countries. We also included a dummy variable to indicate whether the metropolitan area was Canadian or American to adjust for the mortality differentials between the two countries.32 Finally, we tested whether the relation between income inequality and mortality in Canada differed significantly from the US relation and whether the coefficients for median share for Canada differed significantly from zero. The approach involved specifying full models, including all two way interactions, and then specifying reduced models with the effect of interest removed (the multicollinearity present in the fully fitted models made it difficult to assess the slope differences; the approach comparing the error sum of squares of the full and reduced models circumvents the problem). The test statistic entailed a comparison of the error sum of squares of each model and followed an F distribution.33

Results

States and provinces

The median share values ranged from 0.17 (least equal) in Louisiana to 0.23 (most equal) in New Hampshire for the US states, while the range for the Canadian provinces was 0.22 (least equal) for Saskatchewan to 0.24 (most equal) for Prince Edward Island. The median proportion of income received by the less well off half was 0.21 for US states, while for Canadian provinces it was 0.23. There was little overlap between US states and Canadian provinces in regard to income inequality with only Wisconsin, Vermont, Utah, and New Hampshire sharing similar income distributions to the Canadian provinces.

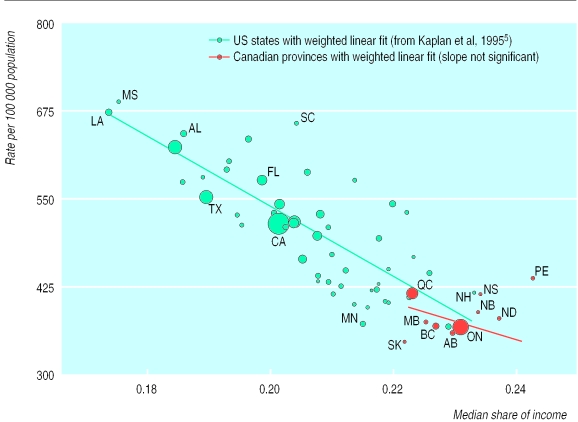

Median share of income was correlated (P<0.01) with infants (r=m-0.69), children/youth (r=−0.62), working age men (r=−0.81), working age women (r=−0.81), elderly men (r=−0.44), elderly women (r=−0.42), and all age (r=−0.68) mortality in combined US states and Canadian provinces calculations. Figure 1 shows a weighted linear fit (the areas of the circles are proportional to the population size) between income inequality and mortality for working age men at the state/provincial levels. The strongest relation with inequality was for working age populations. The Canadian provinces seem almost like a more equitable extension of the US data, by having lower mortality and lower inequality. Within Canada, however, the slope of the weighted regression line was in the expected direction but was not significantly different from zero.

Figure 1.

Mortality in working age men by proportion of income belonging to the less well off half of households, US states (1990) and Canadian provinces (1991). Mortality standardised to Canadian population in 1991. State abbreviations: LA-Louisiana; MS-Mississippi; AL-Alabama; SC-South Carolina; FL-Florida; TX-Texas; CA-California; AR-Arkansas; NH-New Hampshire; MN-Minnesota. Province abbreviations: QC-Quebec; NS-Nova Scotia; NB-New Brunswick; ND-Newfoundland; PE-Prince Edward Island; ON-Ontario; AB-Alberta; BC-British Columbia; MB-Manitoba; SK-Saskatchewan

Metropolitan areas

The populations of the 282 metropolitan areas in the United States ranged from 56 735 (Enid, Oklahoma) to 18 087 251 (New York city) with a median size of 242 847. The populations of the 53 metropolitan areas in Canada ranged from 50 193 (Saint-Hyacinthe, Quebec) to 3 893 046 (Toronto, Ontario) with a median size of 116 100. The median share values ranged from 0.15 (least equal) in Bryan, Texas, to 0.25 (most equal) in Jacksonville, North Carolina, for the United States while the range in Canada was 0.22 (least equal) for Montreal, Quebec, to 0.26 (most equal) for Barrie, Ontario. The median proportion of income received by the less well off half of households for US metropolitan areas was 0.21 while for the Canadian metropolitan areas it was 0.23.

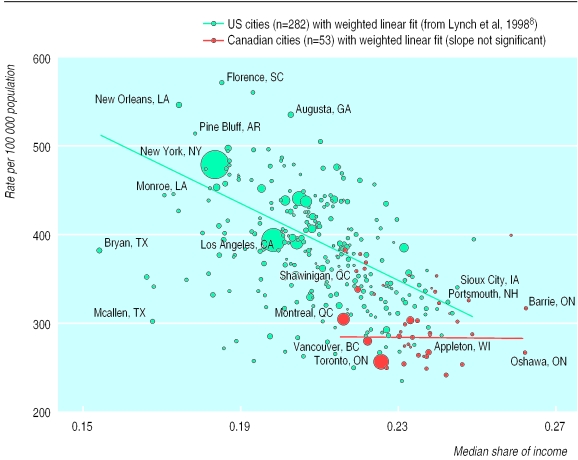

There were significant correlations (P<0.01) between median share and mortality for infants (r=−0.37), children and youth (r=−0.38), the working age population (r=−0.55), the elderly population (r=−0.25), and all ages combined (r=−0.43) for the pooled 335 metropolitan areas in the United States and Canada. Within Canada, however, there was no statistical relation between inequality and mortality at the metropolitan area level as evidenced by the weighted linear fit (dashed line) to the Canadian data points for working age mortality in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mortality in all working age people by proportion of income belonging to the less well off half of households, US (1990) and Canadian metropolitan areas (1991). Mortality standardised to Canadian population in 1991. State abbreviations: LA-Louisiana; GA-Georgia; AR-Arkansas; SC-South Carolina; NY-New York; TX-Texas; CA-California; IA-Iowa; NH-New Hampshire; WI-Wisconsin. Province abbreviations: QC-Quebec; ON-Ontario; BC-British Columbia

In the first set of multiple regression models, the median share was a significant explanatory variable for all but the model of mortality in elderly people for the 282 US metropolitan areas (table). The largest effect was in mortality in working age people, where a 1% increase in the share of household income to the poorer half of the income distribution was associated with a decline in mortality of nearly 22 deaths per 100 000. In general, the size of the effect of the median share variable changed little with the addition of the median state income variable, the second set of regressions. The inclusion of the 53 Canadian metropolitan areas, the third set of regressions, improved the explanatory significance of the models with, for example, the adjusted R2 (squared multiple correction) increasing from 0.02 to 0.27 for infants and from 0.33 to 0.51 for the working age population. The country dummy variable was significant in each of the models and may be interpreted as the difference in mortality between the two countries after adjustment for the distribution of household income and median household income. Thus there were 91 fewer deaths per 100 000 in Canadian metropolitan areas than in US metropolitan areas after adjustment for median share and median income.

Finally, the general linear testing indicated that the slope of the relation between median share and mortality for Canadian metropolitan areas was significantly different than the US slope for children and youth (F1,329=5.98, P<0.05), working age populations (F1,329=8.79, P<0.01), and all age groups combined (F1,329=6.22, P<0.05). In all cases, however, after the three main effects variables (median share, median income, and the dummy country indicator) and all two way interactions in the Canada and US models were accounted for, the slope of the relation between median share and mortality in Canada was not significantly different from zero.

Discussion

Our analysis of data from Canada and the United States has shown that variations in the equality of the income distribution are associated with mortality. The relation was strongest for working age populations but was much weaker in elderly populations. Other research has suggested that differential working age mortality across populations may be a more powerful measure of relative disadvantage than the traditionally studied infant mortality differential.20,34,35 As for the attenuation seen in elderly populations, current household income may not be a useful measure for this group given that income levels before retirement or measures of wealth better reflect their social position.36

There were no significant asociations between income inequality and mortality in Canada at either the provincial or metropolitan area levels, whereas such associations were apparent in the United States. The absence of an effect within Canada may indicate that the relation between income inequality and mortality is non-linear (that is, at higher levels of equality there is a diminishing effect on health) or that the relation between income inequality and mortality is not universal but instead depends on social and political characteristics specific to place. The first explanation suggests that reducing income inequality would be beneficial for population health. The latter explanation suggests that specific policies can be implemented to buffer the health effects of income inequality.15

The juxtaposition of Canadian and US policies in these analyses raises questions about differences in the social and material conditions of the two countries that mute (in Canada) and exaggerate (in the United States) the relation of inequality to mortality. One plausible difference is the greater degree of economic segregation in large US cities.20Such segregation can create a spatial mismatch between workers and jobs and large inequalities in provision of public goods and services (for example, schools, transportation, health care, policing, housing, etc) because of concentrations of people with high social needs in municipalities with low tax bases.37 The population health effects of inequalities in provision of these public goods and others like parks, libraries, and recreation facilities need to be the focus of future research.15,38

Another major difference between the two countries is the way in which resources such as health care and high quality education are distributed. In the United States these resources tend to be distributed by the marketplace so their utilisation tends to be associated with ability to pay; in Canada they are publicly funded and universally available. As a consequence, in the United States an individual's income, in both a relative and absolute sense, is a much stronger determinant of life chances and, in turn, “health chances” than in Canada.

These comments underscore the point that observations of contexts in which income inequality has health consequences and those in which it does not provide opportunities to examine the role of variations in economic and social policy which structure the availability of resources and demands placed on individuals. Collectively, these resources and demands modify the day to day experiences of individuals thereby creating different patterns of health and disease in different places.

What is already known on this topic

Income inequality has been shown to be associated with mortality when countries, US states, and US metropolitan areas have been compared

What this study adds

Data from Canada have been added to the research on the relation between income inequality and mortality, thus providing a more complete picture for North America

Income inequality is strongly associated with mortality in the United States and in North America as a whole, but there is no relation within Canada at either the province or metropolitan area level

Overall, the comparison between Canada and the United States suggests that policies directed toward evening out the income distribution may reduce the effects of inequality on health

Table.

Metropolitan area regression results for US only models (n=282) and combined Canada and US models (n=335)

| Age group and model | Intercept | Median share (%) | Median income (US$1000) | Country dummy | Adjusted R2* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | |||||

| US only | 1341† | −19.73† | — | — | 0.03 |

| US only with income | 1386† | −19.35† | −1.6 | — | 0.02 |

| US-Canada with dummy | 1358† | −18.18† | −1.5 | −280† | 0.27 |

| Child/youth | |||||

| US only | 110† | −2.49† | — | — | 0.11 |

| US only with income | 116† | −2.43† | −0.20† | — | 0.11 |

| US-Canada with dummy | 113† | −2.26† | −0.30† | −18† | 0.35 |

| Working age | |||||

| US only | 848† | −21.71† | — | — | 0.33 |

| US only with income | 838† | −21.80† | 0.40 | — | 0.34 |

| US-Canada with dummy | 826† | −20.92† | 0.20 | −67† | 0.51 |

| Elderly | |||||

| US only | 5255† | −20.58 | — | — | 0.01 |

| US only with income | 5547† | −18.03 | −10.50† | — | 0.03 |

| US-Canada with dummy | 5490† | −14.16 | −11.20† | −399† | 0.16 |

| All ages | |||||

| US only | 1110† | −15.09† | — | — | 0.13 |

| US only with income | 1141† | −14.82† | −1.10 | — | 0.12 |

| US-Canada with dummy | 1127† | −13.84† | −1.30† | −91† | 0.34 |

Squared multiple correction.

P<0.05.

Footnotes

Funding: Statistics Canada, Canadian Population Health Initiative, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (postdoctoral fellowship No 756-98-0194), University of Michigan Initiative on Inequalities in Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Ben-Shlomo Y, White IR, Marmot M. Does the variation in the socioeconomic characteristics of an area affect mortality? BMJ. 1996;312:1013–1014. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7037.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davey Smith G, Egger M. Commentary: understanding it all—health, meta-theories, and mortality trends. BMJ. 1996;313:1584–1585. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7072.1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiscella K, Franks P. Poverty or income inequality as predictors of mortality: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 1997;314:1724–1728. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7096.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flegg A. Inequality of income, illiteracy, and medical care as determinants of infant mortality in developing countries. Popul Stud. 1982;36:441–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan GA, Pamuk E, Lynch JW, Cohen RD, Balfour JL. Income inequality and mortality in the United States: analysis of mortality and potential pathways. BMJ. 1996;312:999–1003. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7037.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy BP, Kawachi, Prothrow-Stith D. Income distribution and mortality: cross sectional ecological study of the Robin Hood index in the United States. BMJ. 1996;312:1004–1007. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7037.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Grand J. Inequalities in health: some international comparisons. Eur Econ Rev. 1987;31:182–191. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Pamuk ER, Cohen RD, Heck KE, Balfour JL, et al. Income inequality and mortality in metropolitan areas of the United States. Am J Public Health 1998;1074-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Rodgers GB. Income and inequality as determinants of mortality: an international cross-section analysis. Popul Stud. 1979;33:343–351. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldmann RJ. Income distribution and infant mortality. Q J Econ. 1992;107:1283–1302. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wennemo I. Infant mortality, public policy and inequality—a comparison of 18 industrialised countries 1950-85. Sociol Health Illness. 1993;15:429–446. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkinson RG. Income and mortality. In: Wilkinson RG, editor. Class and health: research and longitudinal data. London: Tavistock; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkinson RG. Income distribution and life expectancy. BMJ. 1992;304:165–168. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6820.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson M, Daly M. Life expectancy, economic inequality, homicide, and reproductive timing in Chicago neighbourhoods. BMJ. 1997;314:1271–1274. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7089.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynch JW, Davey Smith G, Kaplan GA, House J. Income inequality and health: a neo-material interpretation. BMJ (in press).

- 16.Wilkinson RG. Unhealthy societies: the afflictions of inequality. London: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gravelle H. How much of the relation between population mortality and unequal distribution of income is a statistical artefact? BMJ. 1998;316:382–385. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfson MC, Kaplan G, Lynch J, Ross NA, Backlund E. The relationship between income inequality and mortality is not a statistical artefact: an empirical assessment. BMJ. 1999;319:953–957. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7215.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daly M, Duncan G, Kaplan GA, Lynch JW. Macro-to-micro linkages in the inequality-mortality relationship. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1998;76:315–339. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waitzman NJ, Smith KR. Separate but lethal: the effects of economic segregation on mortality in metropolitan America. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1998;76:341–373. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy BP, Kawachi I, Glass R, Prothrow-Stith D. Income distribution, socioeconomic status, and self rated health in the United States: multilevel analysis. BMJ. 1998;317:917–921. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7163.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soobader M-J, LeClere FB. Aggregation and the measurement of income inequality: effects on morbidity. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:733–744. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeates M. The North American city. 4th ed. New York: Harper and Row; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg M, Mercer J. The myth of the North American city. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Badcock B. Unfairly structured cities. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bourne LS. Social inequalities, polarization, and the redistribution of income within cities: a Canadian example. In: Badcock BA, Browett MH, editors. Developing small area indicators for policy research in Australia. Adelaide: National Key Centre for Social Applications of Geographical Information Systems, University of Adelaide; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murdie RA. The welfare state, economic restructuring, and immigrant flows: impacts on socio-spatial segregation in urban Toronto. In: Musterd S, Ostendorf W, editors. Urban segregation and the welfare state. New York: Routledge; 1998. pp. 64–93. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfson MC, Murphy BB. New view on inequality trends in Canada and the United States. Monthly Labor Rev. 1998;April:3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy KM, Riddell WC, Romer P. Wages, skills and technology in the United States and Canada. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER); 1998. (working paper No 6638). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holzer H. What employers want. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Connell JM. The relationship between health expenditures and the age structure of the population in OECD countries. Health Econ. 1996;5:573–578. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(199611)5:6<573::AID-HEC231>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Statistics Canada. Report on the demographic situation in Canada 1997. Ottawa, ON: Minister of Industry; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neter J, Wasserman W, Kutner MH. Applied linear statistical models: regression, analysis of variance, and experimental designs. 3rd ed. Boston, MA: Irwin; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guest AM, Almgren G, Hussey JM. The ecology of race and socioeconomic distress: infant and working-age mortality in Chicago. Demography. 1998;35:23–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marmot MG, Fuhrer R, Ettner SL, Marks NF, Bumpas LL, Ryfe CD. Contribution of psychosocial factors to socioeconomic differences in health. Milbank Q. 1998;76:403–448. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfson MC, Rowe G, Gentleman JF, Tomiak M. Career earnings and death: a longitudinal analysis of older Canadian men. J Gerontol. 1993;48:S167–S179. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.s167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orfield M. Metropolitics: a regional agenda for community and stability. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press and the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lynch JW, Kaplan GA. Understanding how inequality in the distribution of income affects health. J Health Psychol. 1997;2:297–314. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]