Abstract

AIMS

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors were marketed aggressively and their rapid uptake caused safety concerns and budgetary challenges in Canada and Australia. The objectives of this study were to compare and contrast COX-2 inhibitors and nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (ns-NSAID) use in Nova Scotia (Canada) and Australia and to identify lessons learned from the two jurisdictions.

METHODS

Ns-NSAID and COX-2 inhibitor Australian prescription data (concession beneficiaries) were downloaded from the Medicare Australia website (2001–2006). Similar Pharmacare data were obtained for Nova Scotia (seniors and those receiving Community services). Defined daily doses per 1000 beneficiaries day−1 were calculated. COX-2 inhibitors/all NSAIDs ratios were calculated for Australia and Nova Scotia. Ns-NSAIDs were divided into low, moderate and high risk for gastrointestinal side-effects and the proportions of use in each group were determined. Which drugs accounted for 90% of use was also calculated.

RESULTS

Overall NSAID use was different in Australia and Nova Scotia. However, ns-NSAID use was similar. COX-2 inhibitor dispensing was higher in Australia. The percentage of COX-2 inhibitor prescriptions over the total NSAID use was different in the two countries. High-risk NSAID use was much higher in Australia. Low-risk NSAID prescribing increased in Nova Scotia over time. The low-risk/high-risk ratio was constant throughout over the period in Australia and increased in Nova Scotia.

CONCLUSIONS

There are significant differences in Australia and Nova Scotia in use of NSAIDs, mainly due to COX-2 prescribing. Nova Scotia has a higher proportion of low-risk NSAID use. Interventions to provide physicians with information on relative benefits and risks of prescribing specific NSAIDs are needed, including determining their impact.

Keywords: COX-2 inhibitors, drug utilization, international comparison, NSAIDs, prescribing

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors were marketed aggressively and their rapid uptake caused safety concerns and budgetary challenges in Canada and Australia.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The study showed that there were similarities in the anti-inflammatory prescribing pattern between Australia and Nova Scotia; however, volumes of both ns-NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors prescribed were higher in Australia in the study period. The remarkable increase observed in Australia in NSAIDs use was essentially due to the much higher COX-2 inhibitor use. Differences in regulatory and marketing practices, as well as cultural and historical differences might be some of the reasons for differences in the NSAID prescribing between Australia and Nova Scotia.

Introduction

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been used to decrease pain and inflammation for rheumatological and other conditions for decades [1, 2]. However, their use is not free from side-effects, including gastrointestinal (GI) disorders (from minor dyspepsia through to major ulcers, bleeding and perforation), kidney effects (leading to a variety of problems, such as increased blood pressure or heart failure) and cardiovascular effects [3–5]. The GI adverse effects have been proposed to be related to inhibition of one type of enzyme, cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1); and COX-2 inhibitors were developed to be selective in the inhibition of the ‘inducible’ form associated with inflammation, COX-2 [4]. COX-2 inhibitors were introduced in both Australia and Canada with a recommendation to limit use to those patients at high risk of GI complications or those not responding to traditional NSAID therapy [6, 7]. Nevertheless, after the launch on the market of this new class of drugs, a very rapid take up was observed [8, 9]. However, COX-2 inhibitors have not been as free from adverse effects as might have been predicted [5, 10]. Safety became a major concern, culminating in the worldwide withdrawal of rofecoxib, one of the COX-2 inhibitors (September 2004) due to concerns about cardiovascular adverse effects [4]. In 2006, lumiracoxib, another COX-2 inhibitor, started to be subsidized in Australia, after approval on the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS), the Australian medicines subsidy list, and in Canada. Lumiracoxib's withdrawal was recently announced (August 2007 in Australia and October 2007 in Canada), due to concerns about liver toxicity.

There is a need to improve the safe, appropriate, cost-effective prescribing of drugs in both Canada and Australia [11–15]. However, limited information exists in Canada, or in Australia, evaluating the use, and the uptake of use, of the newer, more expensive medications such as COX-2 inhibitors, and opportunities to learn from experiences in different countries are limited.

Cross-national drug utilization studies can provide information on differences in the effects of access to drug programmes, the effects of formulary policies, the influences on physician prescribing, and the influences on patients' demands (education interventions, marketing activities, etc). Exploration of similarities and differences in usage can lead to planning for policy, for education, and other interventions involving health professionals, patients, and decision makers. Differences in prescribing of nonselective (ns)-NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors between the two jurisdictions had not previously been explored.

Australia and Canada have different healthcare systems, including different reimbursement schemes, different ways of educating health professionals and different lists of subsidized medicines. Both the Australian and Canada's national health insurance programmes are designed to ensure that all residents have reasonable access to medically necessary hospital and physician services. The 10 provinces and three territories of Canada share specific basic standards and common features of coverage as determined by the Canada Health Act, while pharmaceuticals coverage is excluded except in hospitals, and plans are provided by provinces, territories, specific federal programmes (e.g. for veterans and First Nations) or the private sector [16]. Provincial and territorial healthcare plans can vary significantly in terms of drug subsidized, patient contributions and beneficiary subgroups (e.g. children, seniors or social assisted recipients) [16]. In contrast, Australia has a national scheme for medical services and pharmaceuticals.

The objective of this study was to compare and contrast the use of the COX-2 inhibitors and ns-NSAIDs in Nova Scotia (Canada) and Australia in the period 2001–2006. In the longer term, this analysis will be used to develop ways to influence more rational use of these medicines in the two jurisdictions by exchange of ideas and practices.

Methods

Australian data

Medicare Australia is responsible for payment to community pharmacists for prescriptions reimbursed by the PBS. All dispensing of reimbursable prescribed drugs is recorded in a database, with aggregated, de-identified data publicly accessible through a website (http://www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/provider/pbs/stats.jsp). The reimbursement system covers all permanent residents in Australia (PBS beneficiaries). However, there are two classes of PBS beneficiaries: general and concession. Concession beneficiaries consist of those Australian residents eligible for the Commonwealth Seniors Health Card, Health Care Card and Pensioner Concession Card (pensioners, single parents, low-income families and other social security benefit recipients). Concession beneficiaries contribute with a low co-payment (currently AUD$5.30), general beneficiaries contribute with higher co-payments (currently AUD$32.20). Items below the general beneficiary co-payment amount are not captured by the dispensing reimbursement database.

The numbers of eligible concession beneficiaries for Australia were obtained by request from Centrelink (the government agency responsible for social services for the Australian community).

The numbers of prescriptions for concession beneficiaries dispensed during the period January 2001 to December 2006 in Australia, for ns-NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors (Table 1) were downloaded from the Medicare Australia website. The generic compounds were classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system 2006 [17].

Table 1.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs subsidized in Australia and Nova Scotia (M01A) and relative risk categorization for gastrointestinal adverse effect

| AUS | NS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Celecoxib | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Diclofenac | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Etodolac | ✗ | ✓ | |

| Fenoprofen | ✗ | ✓ | |

| Flurbiprofen | ✗ | ✓ | |

| Ibuprofen | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Indomethacin | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Ketoprofen | ✓ | ✓ | Low |

| Ketorolac | ✗ | ✗ | Moderate |

| Lumiracoxib | ✓ | ✗ | High |

| Mefenemic acid | ✓ | ✓ | Nonclassified |

| Meloxicam | ✓ | ✓ | COX-2 inhibitors |

| Nabumetone | ✗ | ✓ | |

| Naproxen | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Piroxicam | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Rofecoxib | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Sulindac | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Tenoxicam | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Tiaprofenic AC | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Valdexoxib | ✗ | ✓ |

Ethical approval was not required in Australia, as aggregated data are publicly available through the Medicare Australia website.

Canadian data

The Nova Scotia Government Pharmacare Program is available to all Nova Scotia seniors aged ≥65 years who have a valid Nova Scotia Health Card and do not have private drug coverage (Seniors' Pharmacare Program) and to those receiving income assistance through the Department of Community Services (Community Services Pharmacare Programs) [18]. Eligible Pharmacare beneficiaries are required to pay a yearly premium plus 33% of the total cost of each prescription from a minimum of CAD$3 to a maximum of CAD$30 per prescription as a co-payment [17]. The Pharmacare drug plans reimburse only a portion of the cost of COX-2 inhibitors (maximum allowable cost, based on cost of selected ns-NSAIDs); the difference has to be paid by the patients, thus creating a price signal to consumers, as the price they pay for COX-2 inhibitors is greater than the price they pay for ns-NSAIDs [18].

Nova Scotia data were obtained as quantity dispensed and number of beneficiaries in each time period for each reimbursable drug from the Population Health Research Unit of the Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, Dalhousie University (http://www.phru.dal.ca/, accessed on 27 November 2007). All data extraction was carried out on secure computer systems using encrypted, unique beneficiary identifiers to maintain patient confidentiality; data were provided in aggregate form as monthly and yearly usage of each drug.

The study obtained ethical approval from Dalhousie University Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Board (May 2007) in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Seniors and community services data from the province of Nova Scotia, Canada were collected for NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors for the period January 2001 to December 2006.

Data analysis

Ns-NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors subsidized in Australia and Nova Scotia during the study period and classified according to M01A ATC classification system were considered (Table 1) [19].

The number of defined daily doses (DDD, 2006 version) per 1000 eligible beneficiaries per day were calculated for all ns-NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors, as described previously [20]. Percentages of COX-2 inhibitors use as a proportion of overall NSAIDs usage were calculated for Australia and Nova Scotia. COX-2 inhibitors available in Australia (celecoxib, rofecoxib, and lumiracoxib) and Nova Scotia (celecoxib, rofecoxib, and valdecoxib) were analysed. Meloxicam has been analysed independently. The Food and Drug Administration classifies meloxicam as a ns-NSAID [21]. However, in Australia meloxicam is classified by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and PBS as a COX-2 inhibitor.

Ns-NSAIDs have been classified by the Gastroenterological Society of Australia into groups of compounds for low, moderate and high risk for GI side-effects (used in usual doses) [22]. This classification is in agreement with other sources in the international literature [23–26]. Using these published criteria, ibuprofen and diclofenac were classified as low risk, aspirin, sulindac, naproxen and indomethacin as moderate risk, and ketoprofen and piroxicam as high risk for GI side-effects. This classification does not include COX-2 inhibitors, nor does it classify for cardiovascular risk.

Drug utilization 90% (DU90%) was calculated. DU90% includes those drugs responsible for 90% of the prescribing within the group of medicines being studied [27]. DU90% is a tool for assessing the overall trends in prescribing over a defined period of time that was introduced by Bergman et al. [27].

DDD calculations were completed using Microsoft Office Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Graphs were obtained using OriginLab (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

As there are differences in the drugs subsidized in the two countries, the WHO/ATC classification of those drugs included in this study are shown in Table 1.

Results

The Australian concession beneficiaries numbered 4938 601 in December 2006, accounting for approximately 24% of the whole population. Older Australians concession beneficiaries, those >65 years old, represented approximately 40% of the concession beneficiaries. In Nova Scotia, eligible beneficiaries numbered 185 864 (20% of the whole population of Nova Scotia), and approximately 60% of those were aged ≥65 years (seniors).

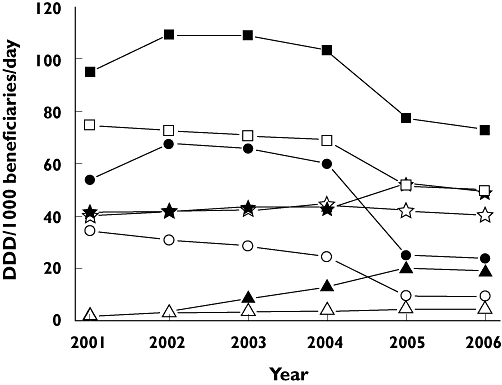

Overall NSAID, ns-NSAID and COX-2 inhibitor dispensing data, over the period 2001–2006, are shown in Figure 1. Overall, NSAID use in Australia was higher over the period; however, the profile over time was similar in the two geographical areas. From 2003, overall NSAID prescribing decreased in both countries (from approximately 103 to 72 DDD per 1000 concession beneficiaries day−1 in Australia, and from approximately 69 to 50 DDD per 1000 concession beneficiaries day−1 in Nova Scotia) (Figure 1). Ns-NSAID use was similar in Australia and Nova Scotia throughout the period. In Australia, an increase in COX-2 inhibitor use was initially observed. In contrast, in the same period COX-2 inhibitor use decreased in Nova Scotia (Figure 1). However, COX-2 inhibitor use subsequently decreased in both jurisdictions, dropping to 25 DDD per 1000 beneficiaries day−1 in Australia and to 9 DDD per 1000 beneficiaries day−1 in Nova Scotia. In Nova Scotia rofecoxib prescribing decreased constantly throughout the period, while increasing in Australia until 2003 (Table 2). Celecoxib prescribing was much higher in Australia throughout the period. Valdecoxib was introduced only in Nova Scotia and its use was very small. Lumiracoxib was marketed in Australia in August 2006. In the last quarter of 2006, a usage of approximately 4 DDD per 1000 beneficiaries day−1 was observed (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Overall nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), nonselective (ns)-NSAID, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor and meloxicam use in Australia and Nova Scotia between 2001 and 2006. COX-2 inhibitors NS (—○—); COX-2 inhibitors AUS ( ); ns-NSAIDs NS (—⋆—); ns-NSAIDs AUS (—⋆—); meloxicam NS (—▵—); meloxicam AUS (—▴—); All NSAIDs NS (—□—); All NSAIDs AUS (

); ns-NSAIDs NS (—⋆—); ns-NSAIDs AUS (—⋆—); meloxicam NS (—▵—); meloxicam AUS (—▴—); All NSAIDs NS (—□—); All NSAIDs AUS ( )

)

Table 2.

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors and meloxicam utilization in Australia and Nova Scotia for the years 2001 to 2006

| Celecoxib | Rofecoxib | Lumiracoxib | Valdecoxib | Meloxicam | COX-2/all NSAIDs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDD per 1000 beneficiaries day−1 | % | |||||||||

| Year | AUS | NS | AUS | NS | AUS | NS | AUS | NS | AUS | NS |

| 2001 | 39 | 21 | 16 | 13 | NA | NA | – | 1 | 57 | 46 |

| 2002 | 43 | 20 | 24 | 11 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 62 | 43 |

| 2003 | 38 | 18 | 27 | 10 | NA | NA | 8 | 3 | 60 | 40 |

| 2004 | 38 | 17 | 22 | 7 | NA | >1 | 13 | 4 | 58 | 36 |

| 2005 | 25 | 10 | – | – | NA | >1 | 20 | 5 | 32 | 18 |

| 2006 | 20 | 9 | – | – | 4 | NA | 19 | 4 | 33 | 19 |

AUS, Australia; NA, not applicable; NS, Nova Scotia.

The percentage of COX-2 inhibitors in the total non steroidal anti-inflammatory usage was different in the two countries (Table 2). In Nova Scotia, it was approximately 46% in 2001 and decreased constantly over the period, going down to 18% (Table 2). In Australia, COX-2 inhibitor prescription percentage reached 62% of total NSAID prescribing (2002). It went down to 32 and 33% in 2005 and 2006, respectively (Table 2).

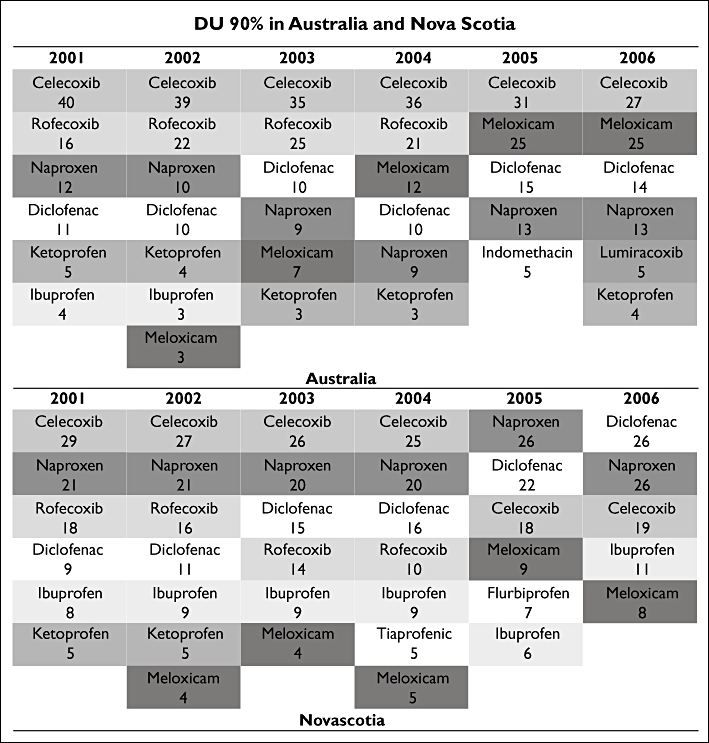

DU90% analysis showed that the most significant difference between the two jurisdictions was due to meloxicam uptake (Figure 2). In Australia, meloxicam entered into the DU90% soon after its launch on the market (2002), and its use increased constantly over the years accounting for 3% in 2002 and 25% in 2005 and 2006. In Nova Scotia, meloxicam prescriptions varied from 4% of total anti-inflammatory prescribing (2002) to 9% in 2005 (Figure 2). The number of items included in the DU90% was similar in the two countries. In some years the five NSAIDs accounted for 90% of the drugs used in that class, in other years the top 90% of drug use was spread over seven drugs both in Australia and Nova Scotia (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) drug utilization 90% (DU90%) in Australia and Nova Scotia between 2001 and 2006

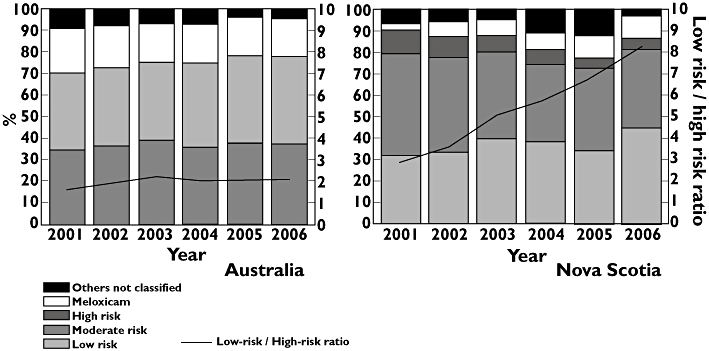

High-risk NSAID use was much higher in Australia; however, it decreased over the years (Figure 3). In contrast, low-risk NSAID prescribing increased in Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia registered a higher usage of those NSAIDs not classified according their relative risk as GI adverse effect (Figure 3). Differences in low-risk/high-risk NSAID use ratios were observed between Australia and Nova Scotia (P≤ 0.05). Low-risk/high-risk ratio was approximately 2 all over the period in Australia. In Nova Scotia, the low-risk/high-risk ratio increased (from 3 to 8).

Figure 3.

Nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (ns-NSAID) utilization by risk for gastrointestinal (GI) side-effects (blocks, left axis) and low/high risk ratio (lines, right axis) in Australia and Nova Scotia between 2001 and 2006. others not classified ( ); meloxicam (

); meloxicam ( ); high risk (

); high risk ( ); moderate risk (

); moderate risk ( ); low risk (

); low risk ( ); Low-risk / High-risk ratio (

); Low-risk / High-risk ratio ( )

)

Discussion

This study has confirmed that comparison of NSAID and COX-2 inhibitor utilization between Australia and Nova Scotia was feasible and provided some interesting contrasts. There were similarities in the anti-inflammatory prescribing pattern in the two countries. However, volumes of both ns-NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors prescribed were higher in Australia throughout the period.

The remarkable increase observed in Australia in NSAIDs use was essentially due to a change in meloxicam prescription consequent to rofecoxib withdrawal. When rofecoxib was withdrawn in Australia, it appeared that patients were most likely to be switched to meloxicam.

Differences in ns-NSAID prescribing between the two jurisdictions were also highlighted by ns-NSAID use stratified for risk of GI effects. In Australia, the percentage of ns-NSAIDs with higher risk of GI bleeding was much higher than in Nova Scotia, and the use of low-risk ns-NSAIDs decreased in Australia, whereas this increased in Nova Scotia. The low-/high-risk ratio continuously improved (increased) in Nova Scotia, whereas it was steady in Australia. By the end of 2006, in Australia the unclassified items (mostly meloxicam) accounted for approximately 40% of overall ns-NSAID utilization, fourfold higher then in Nova Scotia.

In Australia, celecoxib and rofecoxib uptake reached values that were two- to threefold higher than in Nova Scotia. There was a cost signal to consumers operating in Nova Scotia, with a higher co-payment required for COX-2 inhibitors, likely to have decreased demand. The co-payment for consumers in Australia was the same for all NSAIDs.

The DU90% prescribing indicator was also useful in this study to demonstrate how quickly COX-2 inhibitors penetrated the market and to highlight the differences between the two countries. The DU90% drew attention to the changes in choice of drug that occurred in each jurisdiction when rofecoxib was withdrawn.

Differences in regulatory and marketing practices, including the price differential to consumers, as well as cultural and historical differences might explain some of differences in NSAID prescribing between Australia and Nova Scotia [28]. The differences in the prescription pattern in meloxicam use, observed between Australia and Nova Scotia, seem to be attributable to the different influences on health professionals achieved by specialists, pharmaceutical company marketing or continuing medical education. Bower et al. conducted a study to explore the factors that influence the choice of medications for osteoarthritis (OA) in seniors in Nova Scotia [29]. According to Bower et al., advertising did not appear to be particularly influential in the choice of OA medications in general [29]. In contrast, in Australia media sources created high expectation in patients and, as a consequence, COX-2 inhibitor uptake immediately after their launch appeared to be very high [20, 30]. In Australia, meloxicam was introduced and advertised as a COX-2 inhibitor [31, 32]. The TGA explicitly referred to meloxicam as a COX-2 inhibitor presenting it together with celecoxib. Consequently, meloxicam in Australia penetrated the market and was perceived by prescribers as COX-2 selective [31–33]. In Canada, announcements and publications were more inconsistent [34–37]. Publications issued by Canadian institutions referred to meloxicam as either a COX-2 inhibitor or a ns-NSAID [34–37]. In Nova Scotia clinicians appear to have been educated about meloxicam nonselectivity [38]. However, some discrepancies emerged from the literature. Early clinical trials such as a 12-week, double-blind, multiple-dose, placebo-controlled trial suggested that meloxicam might have had some advantages in favour of GI toxicity [39]. In contrast, a meta-analysis conducted by Richy et al. showed that meloxicam had a better GI profile when compared with naproxen and diclofenac, but no differences were observed when compared with ibuprofen [24]. On the other hand, Singh et al. showed that meloxicam was not different from naproxen in terms of GI toxicity [40].

Discrepancies in prescribing between countries can also emerge from differences in formulary and drugs made available in each jurisdiction. In Australia, lumiracoxib obtained approval to be listed on the PBS in August 2006. Lumiracoxib was never subsidized in Nova Scotia. In contrast, in Nova Scotia valdecoxib was available, but not in Australia.

Differences between Australia and Nova Scotia in reimbursement policies may also have led to the divergences observed in the pattern of NSAID prescribing. In Australia, patients holding a concession card that receive a prescription for a COX-2 inhibitor are required to contribute with a co-payment of only AUD$5.30 per script. In Nova Scotia patients are required to pay 33% of the total cost of each prescription, and more if it is above the maximum allowable cost, as COX-2 inhibitors are. This policy in Nova Scotia might have been one of the reasons for the much lower COX-2 inhibitor use. Kephart et al., in a study conducted in Nova Scotia, showed that the introduction of a CAD$3 co-payment reduced the use of H2 blockers and oral antihyperglycaemics [41]. Other studies had demonstrated that cost-sharing policies can decrease drug utilization internationally [42–44]. Similarly in Quebec in 2003 in patients >65 years old, 70% of all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use was due to COX-2 inhibitors because of lack of formulary restriction policies on their use [45].

Finally, use and implementation of guidelines and educational programmes could have been the reason for different patterns in NSAID prescribing in Australia and Nova Scotia. A number of intervention strategies (academic detailing [46–48], distribution of newsletters [49, 50], prescriber feedback [51, 52], visual and audio aids, posters, brochures or fliers [53]) have been described and considered successful in influencing health behaviour [54–56].

In Nova Scotia, a province-wide academic detailing programme on OA was implemented in 2002 (Osteoarthritis Management in 2002) [38]. In Australia, similar programmes were implemented in 2003 and 2006 by the National Prescribing Service (NPS). In 2003, the NPS started an educational programme known as ‘Optimizing safe and effective use of analgesics in musculoskeletal pain’, and in August 2006 an academic detailing programme on the same topic was repeated (‘Analgesic choices in persistent pain, focusing on best practice analgesic treatment in persistent, non-cancer pain’). The programmes intended to reinforce key messages about efficacy and safety of the different anti-inflammatories available, respectively, in Australia and Nova Scotia. Our analysis did not highlight any particularly sharp decline after the programme implementation [57]. Similarly, in Australia, it was not possible to establish whether the prescription trend observed from 2003 or from 2006 had any correlation with the programme implemented by the NPS. Lumiracoxib was withdrawn from the Australian market in August 2007, and at the time of its withdrawal lumiracoxib prescribing was still growing rapidly.

The trends in prescription and changes in the distribution of NSAIDs in our analysis have confirmed findings from other studies [58–62]. In the Norwegian population, COX-2 utilization was reported to have decreased by approximately 80% after rofecoxib was withdrawal [59]. Similarly, in Germany, over 71 million DDDs month−1 were dispensed for COX-2 before the withdrawal and only approximately 10 million DDDs month−1 were dispensed after rofecoxib withdrawal [61]. Also, meloxicam prescribing increased in Germany (+46%), Scotland (+95%) and in the USA (+167%) in the 12 months following rofecoxib withdrawal in 2004 [60, 63, 64]. Also, it has been reported that in 2005 meloxicam sales increased by 118% in the USA [62].

The study has some limitations. There were differences in demographics and population characteristics. Australian concession beneficiaries and Nova Scotia seniors represent a similar proportion of the total population (10% in Australia and 12% in Nova Scotia). However, the elderly (>65 years) represent 40% of the eligible beneficiaries in Australia (40% of 24%) compared with 60% in Nova Scotia (60% of 20%). Nevertheless, the advantage in selecting Australian concession beneficiaries is that all claims processed will be captured, as the costs of all medications are above co-payment and also this population segment (seniors, welfare recipients) is most comparable to other countries that subsidise prescription medicines only for this limited population, as happens in Nova Scotia.

It could be argued that comparing a whole country (Australia) with one province of Canada (Nova Scotia) is not valid. However, Canadian provinces all have different pharmaceutical reimbursement schemes, and it is not possible to draw conclusions about influences on medication use across the whole of Canada as it is across Australia, which has just one national scheme. Kasman and Badley have conducted a comparative analysis within five different provinces of Canada (British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Saskatchewan and Alberta). The study revealed that all the provinces showed similar patterns in ns-NSAID prescribing [65]. As soon as COX-2 inhibitors were released onto the Canadian market (1999), ns-NSAID prescribing declined whereas COX-2 inhibitor use increased quickly [65]. However, COX-2 inhibitor use varied widely in the different provinces, as would be expected from the different policies for subsidy of these medicines [66]. An extremely low rate of COX-2 inhibitor prescribing was observed in British Columbia [65]. In British Columbia COX-2 inhibitors can be prescribed only under ‘exceptional circumstances’ (only available through special authority to certain patients). Similarly, in Saskatchewan individuals could receive COX-2 inhibitors only if coverage was requested by a physician and had prior approval by the provincial drug plan (before 2000) [65]. It is more useful in the present study to use one province of Canada and compare that one system with the one system existing in Australia.

An additional limitation was ecological fallacy. Data gathered for this study described groups of individuals (ecological study) assuming that all members of the populations studied shared the same potential for exposure to NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors. However, there may be differences between population subgroups [66]. Nevertheless, Australian concession beneficiaries and Nova Scotia seniors and community health beneficiaries have been shown in previous studies to be suitable for international comparison purposes [67, 68].

An additional limitation is that over-the-counter medications are not captured in Australia and Nova Scotia. Therefore, it is possible that we underestimated the volume of ns-NSAID utilization. Moreover, in Australia, prescription data are not linked to other data sources (e.g. medical services or hospitalizations). Hence, it was not possible to establish if the drug prescription was appropriate, if indication and regimen was correct (e.g. correct dosage and/or duration); neither was it possible to complete any analysis of comorbidity and/or co-prescription use, or investigate whether health outcomes were in fact different and associated with differential use of NSAIDs.

Many approaches to attempt to provide safer and cost-effective therapies have been identified [2–6]. Our study seemed to suggest that policy implemented in Nova Scotia (higher patient contributions toward the cost of COX-2 inhibitor prescription) may have been a contributor to more limited prescribing in Nova Scotia.

Implementing specific strategies may assist future costs and volumes of prescriptions [15, 69–73]. Gleason et al., in a study evaluating the effects of a COX-2 inhibitor prior authorization programme, have shown that the plan implementation assisted in cost containment [74]. Similarly, Siracuse et al., in a study to explore the impact of the prior authorization programme on Medicaid pharmacy expenditures and utilization of NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors, showed that the overall expenditures on COX-2 inhibitors for Nebraska Medicaid dropped by 50% [75]. Also, the study showed that the overall pharmacy expenditures for those patients who switched from a COX-2 inhibitor to an NSAID or other pain reliever declined by approximately 35% [75].

No formal restriction on COX-2 inhibitor prescribing exists in Australia; it is possible that a stricter limitation to COX-2 inhibitor prescribing may have prevented such rapid and high uptake, with perhaps a price signal to consumers being a useful component.

In conclusion, the current study has shown that overall NSAID prescribing was much higher in Australia in the period 2001–2006. COX-2 inhibitor prescribing appeared to have influenced markedly NSAID prescribing both in Australia and Nova Scotia by increasing total NSAID use. Total NSAID use dropped only after rofecoxib withdrawal, confirming that prescribers, most likely, perceived the safety concerns reported with rofecoxib as a class effect, reducing COX-2 inhibitor prescribing. However, meloxicam prescribing continued to increase in both countries, and sharply in Australia where it is considered a COX-2 inhibitor. Thus, the use of COX-2 inhibitors in Australia is still a concern.

Further studies to better understand the adherence to prescribing guidelines and policies and the divergences observed in the two countries, in particularly in COX-2 inhibitor use, may be useful.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the funding of Green Shield Canada for the extraction of the Nova Scotia data. The opinions of the authors expressed are their own and not those of Green Shield Canada. I.S. holds a Canadian Health Services Research Foundation/Canadian Institutes of Health Research Chair in Health Services Research, cosponsored by Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation (Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada). Nova Scotia data were obtained from the Population Health Research Unit, Dalhousie University. At the time of this work, N.B. was a visiting PhD student at the College of Pharmacy, Dalhousie University, funded by the Graduate School Research Travel Grant from the University of Queensland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hawkins C, Hanks G. The gastoduodenal toxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:140–51. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones R. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug prescribing: past, present, and future. Am J Med. 2001;110:4S–7S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tannenbaum H, Davis P, Russell AS, Atkinson MH, Maksymowych W, Huang SH, Bell M, Hawker GA, Juby A, Vanner S, Sibley J. An evidence-based approach toprescribing NSAIDs in musculoskeletal disease: a Canadian consensus. Can Med Assoc J. 1996;155:77–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermann M, Ruschitzka F. Coxibs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiovascular risk. Intern Med J. 2006;36:308–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kearney P, Baignent C, Godwin J, Halls H, Emerson J. Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2006;332:1302–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7553.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tannenbaum H, Bombardier C, Davis P, Russell A, Group TCCC. An evidence-based approach to prescribing nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Third Canadian Consensus Conference. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Therapeutic Guidelines: Rheumatology Writing Group. Therapeutic Guidelines: Rheumatology. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barozzi N, Tett S. Use of non selective non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, COX-2 inhibitors and Paracetamol. In: APSA-ASCPT. Melbourne; 2005.

- 9.Mamdani M, Juurlink DN, Kopp A, Naglie G, Austin PC, Laupacis A. Gastrointestinal bleeding after the introduction of COX 2 inhibitors: ecological study. BMJ. 2004;328:1415–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38068.716262.F7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Logan R. Risk of adverse gastrointestinal outcomes in patients taking cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors or conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: population based nested case–control analysis. BMJ. 2005;331:1310–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7528.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Pharmacists Association. Submission to the Romanov Commission on the Future of Health Care Canada. CphA; 2001. Available at http://www.pharmacists.ca/content/about_cpha/whats_happening/government_affairs/pdf/romanow.pdf (last accessed 27 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Office of the Auditor General Canada. Management of Federal Drug Benefit Programs. OAG; 2004. Available at http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/domino/reports.nsf/html/20041104ce.html (last accessed 5 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health Canada. National Pharmaceuticals Strategy. Health Canada; 2005. Available at http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/media/nr-cp/2005/2005_96bk2_e.html (last accessed 25 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Prescribing Service. Minimising the risk of using analgesic for musculoskeletal pain. NPS Newsletter 2003; 28.

- 15.National Prescribing Service. Proton Pump Inhibitors: Too Much of a Good Thing? Sydney: NPS; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Government of Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia's Health Insurance Plan. Government of Nova Scotia; 2006. Available at http://www.gov.ns.ca/health/msi/ (last accessed 24 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Government of Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia Pharmacare Programs. The Nova Scotia Seniors' Pharmacare Program. Government of Nova Scotia; 2007. Available at http://gov.ns.ca/heal/pharmacare/pubs/Seniors_Information_Booklet_2007.pdf (last accessed 30 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Government of Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia Pharmacare Formulary. Government of Nova Scotia; 2007. Available at http://www.gov.ns.ca/health/Pharmacare/formulary.asp (last accessed 31 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC Index with Ddds

- 20.Barozzi N, Tett S. What happened to the prescribing of other COX-2 inhibitors, paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs when rofecoxib was withdrawn in Australia? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:1184–91. doi: 10.1002/pds.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis C, Langley CA, Marriott JF, Wilson KA. A comparison of antibiotic prescribing indicators and medicines management scoring in secondary care. Int J Pharm Pract. 2003;11:R54. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gastroenterological Society of Australia. NSAID Therapy – Maximizing the Benefit, Minimizing the Risk. GESA; 2004. Available at http://www.gesa.org.au/ (last accessed 4 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laine L. Gastrointestinal effects of NSAIDs and coxibs. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:S32–40. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00629-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richy F, Bruyere O, Ethgen O, Rabenda V, Bouvenot G, Audran M, Herrero-Beaumont G, Moore A, Eliakim R, Haim M, Reginster JY. Time dependent risk of gastrointestinal complications induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use: a consensus statement using a meta-analytic approach. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:759–66. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.015925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gabriel SE, Jaakkimainen L, Bombardier C. Risk for serious gastrointestinal complications related to use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs – a meta analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:787–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-10-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiroli S, Chinellato A, Didoni G, Mazzi S, Lucioni C. Utilisation pattern of nonspecific nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and COX-2 inhibitors in a local health service unit in northeast Italy. Clin Drug Investig. 2003;23:751–60. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200323110-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergman U, Popa C, Tomson Y, Wettermark B, Einarson T, Aberg H, Sjögvist F. Drug utilization 90% – a simple method for assessing the quality of drug prescribing. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:113–8. doi: 10.1007/s002280050431. PMID: 9626914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor D. Medicine in Europe – prescribing in Europe – Forces for change. BMJ. 1992;304:239–42. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6821.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bower K, Frail D, Twohig P, Putnam W. What influences seniors' choice of medications for osteoarthritis? Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:342–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiropractic & Osteopathic College of Australasia. Celebrex Controversy. Chiropractic & Osteopathic College of Australasia; 2001. Available at http://www.coca.com.au/newsletter/2001/MAR0109a.htm (last accessed 5 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department of Health and Aging TGA. Status of Action on Products Containing Meloxicam. Department of Health and Aging TGA; 2005. Available at http://www.tga.gov.au/media/2005/050415-meloxicam.htm (last accessed 27 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Prescribing Service. Elevated Cardiovascular Risk with NSAIDs? RADAR; 2005. Available at http://www.npsradar.org.au/site.php?page=1&content=/npsradar/content/nsaids.html (last accessed 27 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Department of Health and Ageing. Regulator Takes Tough Action on Arthritis Drugs (*Amended) Therapeutic Good Administration; 2005. Available at http://www.tga.gov.au/media/2005/050225_cox2.htm (last accessed 19 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health Canada. Safety and Regulatory Information Regarding Celebrex® (Celecoxib), Bextra™ (Valdecoxib), and Meloxicam Subsequent to the Withdrawal of Vioxx® (Rofecoxib) Health Canada; 2004. Available at http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/media/advisories-avis/_2004/2004_50bk1_e.html (last accessed 16 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Health Ontario. Drugs Details. Health Ontario; 2007. Available at http://www.healthyontario.com/DrugDetails.aspx?brand_id=1963&brand_name=ratio-Meloxicam (last accessed 27 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.RxCC Rx Care Canada. Prescription Drugs. RxCC Rx Care Canada; 2004. Available at http://www.rxcarecanada.com/mobicox.asp?prodid=2030 (last accessed 27 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Arthritis Society. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) The Arthritis Society; 2006. Available at http://www.arthritis.ca/tips%20for%20living/understanding%20medications/non%20steroidal/default.asp?s=1 (last accessed 27 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dalhousie Continuing Medical Education. Academic Detailing Service Resources. Osteoarthritis Management in 2002. Dalhousie Continuing Medical Education; 2002. Available at http://cme.medicine.dal.ca/ad_resources.htm#OA (last accessed 12 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yocum D, Fleischmann R, Dalgin P, Caldwell JR, Hall D, Roszko P. Safety and efficacy of meloxicam in the treatment of osteoarthritis: a 12-week, double-blind, multiple-dose, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2947–54. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.19.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh G, Lanes S, Triadiafalopulos G. Risk of serious upper gastrointestinal and cardiovascular thromboembolic complications with meloxicam. Am J Med. 2004;11:100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, Kephart GC, Skedgel C, Sketris I, Grootendorst I, Hoar J, Sommers E. The Effect of Changes in Co-payment and Premium Policies on the Use of Prescription Drugs in the Nova Scotia Seniors' Pharmacare Program. 2003.

- 42.Blustein J. Drug coverage and drug purchases by medicare beneficiaries with hypertension. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000;19:219–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huttin C. The use of prescription charges. Health Policy. 1994;27:53–73. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lundberg L, Johannesson M, Isacson DGL, Borgquist L. Effects of user charges on the use of prescription medicines in different socio-economic groups. Health Policy. 1998;44:123–34. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(98)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Health Canada. Comments on the Report from Expert Advisory Panel on the Safety of COX-2 Selective Non-Steroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs (NSAIDS) 19 May 2006.

- 46.O'Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, Forsetlund L, Bainbridge D, Freemantle N, Davis D, Haynes RB, Harvey E. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2. CD000409. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gjelstad S, Fetveit A, Straand J, Dalen I, Rognstad S, Lindbaek M. Can antibiotic prescriptions in respiratory tract infections be improved? A cluster-randomized educational intervention in general practice – The Prescription Peer Academic Detailing (Rx-PAD) Study [ NCT00272155. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hennessy S, Leonard CE, Yang W, Kimmel SE, Townsend RR, Wasserstein AG, Ten Have TR, Bilker WB. Effectiveness of a two-part educational intervention to improve hypertension control: a cluster-randomized trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1342–7. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.9.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Horn FE, Mandryk JA, Mackson JM, Wutzke SE, Weekes LM, Hyndman RJ. Measurement of changes in antihypertensive drug utilisation following primary care educational interventions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:297–308. doi: 10.1002/pds.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor-Davis S, Smiciklas-Wright H, Warland R, Achterberg C, Jensen GL, Sayer A, Shannon B. Responses of older adults to theory-based nutrition newsletters. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:656–64. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(00)00193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roughead E, Pratt N, Peck R, Gilbert A. Improving medication safety: influence of a patient-specific prescriber feedback program on rate of medication reviews performed by Australian general medical practitioners. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:797–803. doi: 10.1002/pds.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zwar N, Henderson J, Britt H, McGeechan K, Yeo G. Influencing antibiotic prescribing by prescriber feedback and management guidelines: a 5-year follow-up. Fam Pract. 2002;19:12–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lambert MF, Masters GA, Brent SL. Can mass media campaigns change antimicrobial prescribing? A regional evaluation study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:537–43. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ioannidis G, Papaioannou A, Thabane L, Gafni A, Hodsman A, Kvern B, Johnstone D, Plumley N, Baldwin A, Doupe M, Katz A, Salach L, Adachi JD. Canadian Quality Circle pilot project in osteoporosis – rationale, methods, and feasibility. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:1694–700. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCabe MP, Davison TE, George K. Effectiveness of staff training programs for behavioral problems among older people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11:505–19. doi: 10.1080/13607860601086405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Monette J, Miller MA, Monette M, Laurier C, Boivin JF, Sourial N, Le Cruquel JP, Vandal A, Cotton-Montpetit M. Effect of an educational intervention on optimizing antibiotic prescribing in long-term care facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1231–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Graham S, Hartzema A, Sketris I, Winterstein A. Effect of an academic detailing intervention on the utilization rate of cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:749–56. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Furu K, Skurtveit S, Slørdal L. Use of selective COX-2 inhibitors in Norway before and after the Withdrawal of rofecoxib – Norwegian Prescription Database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(Suppl. 1):S243–4. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoebert J, Stolk P, Belister S, Leufkens H, Martins A. The impact of the withdrawal of rofecoxib on the use of other analgesics and proton pump inhibitors – a time series analysis in Portugal. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(Suppl. 1):S166. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schussel K, Schulz M. Prescribing of COX-2 inhibitors in Germany after safety warnings and market withdrawals. Pharmazie. 2006;61:878–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Teeling M, Bennett K, O'Connor H, Feely J. How did the withdrawal of rofecoxib impact on prescribing of non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:637–8. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verispan VONA. Top 200 Brand-name Drugs by Retail Dollars in 2005. Verispan; 2006. Available at http://drugtopics.modernmedicine.com/drugtopics/data/articlestandard//drugtopics/082006/309440/article.pdf (last accessed 22 February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Williams D, Singh M, Hind C. The effect of the withdrawal of rofecoxib on prescribing patterns of COX-2 inhibitors in Scotland. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:366–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun SX, Lee KY, Bertram CT, Goldstein JL. Withdrawal of cox-2 inhibitor rofecoxib and valdecoxib: impact on NSAID and PPI prescriptions and expenditures. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;8:1859–66. doi: 10.1185/030079907X210561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kasman N, Badley E, Health Canada . Arthritis in Canada. An Ongoing Challenge. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2003. Arthritis-related prescription medicines. Available at http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/ac/ac_9e-eng.php (last accessed 4 April 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coggon D, Rose G, Barker D. Ecological studies. 2008. Available at http://www.bmj.com/epidem/epid.6.html (last accessed 19 March.

- 67.Cooke C, Nissen L, Sketris I, Tett S. Quantifying the use of the statin antilipemic drugs: comparisons and contrasts between Nova Scotia, Canada, and Queensland, Australia. Clin Ther. 2005;27:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tett S, Smith AJ, Sketris I, Cooke C, Gardner DM, Kisely S. A comparison of benzodiazepine and related drug use in Nova Scotia, Canada and Australia. 4th Annual Canadian Therapeutics Congress; Halifax Nova Scotia. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Prontuario Farmaceutico Nazionale

- 70.PharmaCare. BCPharmaCare Newsletter. 2005;5:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nova Scotia Department of Community Services. Proton Pump Inhibitors – Policy changes. May Bulletin 2003.

- 72.National Prescribing Service. GORD and non-ulcer dyspepsia. NPS Newsletter 2001; 14.

- 73.National Prescribing Service. Proton Pump Newsletter Inhibitors. NPS 2006; 46.

- 74.Siracuse MV, Vuchetich PJ. Impact of Medicaid prior authorization requirement for COX-2 inhibitor drugs in Nebraska. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:435–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.LaPensee K. Analysis of a prescription drug prior authorization program in a Medicaid health maintenance organization. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9:36–44. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]