Abstract

Background: Extracapsular tumor spread (ECS) has been identified as a possible risk factor for breast cancer recurrence, but controversy exists regarding its role in decision making for regional radiotherapy. This study evaluates ECS as a predictor of local, axillary, and supraclavicular recurrence.

Patients and methods: International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial VI accrued 1475 eligible pre- and perimenopausal women with node-positive breast cancer who were randomly assigned to receive three to nine courses of classical combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil. ECS status was determined retrospectively in 933 patients based on review of pathology reports. Cumulative incidence and hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated using methods for competing risks analysis. Adjustment factors included treatment group and baseline patient and tumor characteristics. The median follow-up was 14 years.

Results: In univariable analysis, ECS was significantly associated with supraclavicular recurrence (HR = 1.96; 95% confidence interval 1.23–3.13; P = 0.005). HRs for local and axillary recurrence were 1.38 (P = 0.06) and 1.81 (P = 0.11), respectively. Following adjustment for number of lymph node metastases and other baseline prognostic factors, ECS was not significantly associated with any of the three recurrence types studied.

Conclusions: Our results indicate that the decision for additional regional radiotherapy should not be based solely on the presence of ECS.

Keywords: axillary recurrence, breast cancer, extracapsular spread, extranodal invasion, loco-regional relapse

introduction

The results of trials from Denmark [1, 2] and British Columbia [3] have revived not only the discussion about postmastectomy radiotherapy but also about additional regional irradiation as these trials used comprehensive treatment fields that included the draining lymph nodes. A recent survey on the current radiotherapeutic management of invasive breast cancer in North America and Europe found marked differences in physician opinions, e.g. internal mammary chain irradiation was offered more often by European than North American radiation oncologists, whereas those from North America were more likely to irradiate the supraclavicular fossa and axilla [4]. Marked differences have also been reported by an informal survey within participating centers of the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG; formerly the Ludwig group); this survey has shown that in several centers, postmastectomy radiation therapy was given to patients with one to three positive lymph nodes only in the presence of additional risk factors; furthermore, these risk factors, especially extracapsular tumor spread (ECS) of axillary lymph nodes, also influenced the decision about regional irradiation (Radiation Oncology Task Force, IBCSG, unpublished data, April 2002).

ECS in axillary lymph node metastases is often associated with locoregional failure (LRF) in breast cancer [5]. In a previous report from our group, premenopausal patients with ECS experienced a higher LRF rate as well as a worse disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) [6]. These worse outcomes were statistically significant in univariable analyses, but not after adjusting for the number of positive nodes. In contrast, ECS with an extent of ≥2 mm was a significant predictor of increased risk of LRF in uni- and multivariable analyses, overall and in the subgroup of T1/T2 tumors with one to three positive nodes in another report [5].

There is still controversy about the necessity of regional irradiation in general, as well as in the presence of ECS, as only a few publications have evaluated the prognostic role of ECS and even fewer reports have dealt with the different sites of relapse in these patients. The purpose of this retrospective analysis is to evaluate the prognostic impact of ECS on the risk of local, axillary, and supraclavicular recurrence in node-positive premenopausal breast cancer patients treated within one large randomized trial.

materials and methods

patients and treatments

From July 1986 to April 1993, 1475 eligible pre- and perimenopausal women with node-positive breast cancer were randomly assigned to receive three to nine courses of classical combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil (CMF) in a 2 × 2 factorial design: (i) CMF for six consecutive courses on months 1–6; (ii) CMF for six consecutive courses on months 1–6 plus three single courses of reintroduction CMF given on months 9, 12, and 15; (iii) CMF for three consecutive courses on months 1–3; (iv) CMF for three consecutive courses on months 1–3 plus three single courses of reintroduction CMF given on months 6, 9, and 12 (IBCSG Trial VI) [7]. At 10 years' median follow-up, there were no significant differences in DFS or OS among or between the four treatment groups in the eligible patient population. All patients had a histologically proven node-positive unilateral breast cancer, classified as T1a, T1b, T2a, T2b or T3a, pN1 M0 [International Union Against Cancer (UICC) 1987], with either estrogen receptor (ER)-positive or ER-negative status known. Surgery of the primary tumor was defined in the protocol as either a total mastectomy with axillary clearance and no radiotherapy or a breast-conserving procedure (quadrantectomy or lumpectomy) with axillary lymph node dissection and subsequent local radiotherapy. For women treated with breast-conserving surgery, radiotherapy was postponed until the end of the initial phase of chemotherapy (three or six courses). Details of eligibility, follow-up, patient characteristics, and outcome for Trial VI have been previously reported [7].

ascertainment of ECS

Whether ECS was present or not was not asked on the trial case report forms. This information was obtained retrospectively by reviewing the protocol-required pathology reports for the 1475 eligible cases. Determination of the presence or absence of ECS was on the basis of the reported tumor–node–metastasis (TNM) category (UICC 1987) or, if the TNM classification was not provided or not decisive (e.g. pN1biv), by a clear statement in the pathology report about the presence or absence of ECS. If the lymph node capsule was infiltrated but not penetrated, this was considered ECS absent. Any penetration of the capsule was rated as ECS present. It was not possible to determine the extent of ECS as this information was seldom available. The ECS status could be determined for 933 patients (63%), and these patients form the basis for this report. The role of ECS on LRF, DFS, and OS was recently published [6].

statistical analysis

This analysis considered the following three types of locoregional recurrences: local, axillary, and supraclavicular. Local recurrence included chest wall or mastectomy scar for patients whose definitive surgery was mastectomy or ipsilateral breast recurrence for those who received a breast-conserving procedure. Axillary recurrence included ipsilateral axillary nodes and/or soft tissue of the axilla. Only the first documented recurrence was considered, but the recurrence may have been in combination with other sites. Internal mammary recurrence was also considered; however, only one such event was recorded in the database, so this end point was not analyzed.

Time to recurrence was determined as the number of years from randomization until the first proven recurrence. If no recurrence was documented, then time to recurrence was censored at the last follow-up time. Statistical methods for competing risks were used including cumulative incidence and competing risks regression analysis [8–10]. Analysis for each type of recurrence was carried out separately. For each type of recurrence, all other types (and death) were considered competing risks. When evaluating a particular recurrence type, only those other types of recurrence not in combination with the type of interest were considered competing risks. Comparisons of cumulative incidence curves were based on a K-sample test procedure [9]. All statistical tests based on competing risks regression were Wald tests [10]. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The analysis considered the following covariates: ECS, randomized treatment group, type of surgery, age, ER status, number of involved lymph nodes, number of lymph nodes examined, tumor size, and vessel invasion, grouped as shown in Table 1. In descriptive analysis, number of positive nodes was classified into five groups (1, 2–3, 4–6, 7–9, or 10+), while in regression analysis, two groups were used (1–3 or 4+). In descriptive analysis, number of nodes examined was classified into seven groups (1–4, 5–7, 8–10, 11–15, 16–20, 21–30, or 31+), while in regression analysis, patients were divided into quartiles.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Total | ECS | No ECS | P value | |

| Number (%) |

||||

| Total | 933 (100) | 462 (100) | 471 (100) | |

| Age, years | ||||

| <40 | 181 (19) | 81 (18) | 100 (21) | 0.15 |

| ≥40 | 752 (81) | 381 (82) | 371 (79) | |

| Estrogen receptor status | ||||

| Negative | 269 (29) | 132 (29) | 137 (29) | 0.86 |

| Positive | 664 (71) | 330 (71) | 334 (71) | |

| No. of positive nodes | ||||

| 1 | 303 (32) | 84 (18) | 219 (46) | <0.0001 |

| 2–3 | 301 (32) | 135 (29) | 166 (35) | |

| 4–6 | 159 (17) | 102 (22) | 57 (12) | |

| 7–9 | 84 (9) | 67 (15) | 17 (4) | |

| ≥10 | 86 (9) | 74 (16) | 12 (3) | |

| No. of nodes examined | ||||

| 1–4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.19 |

| 5–7 | 18 (2) | 5 (1) | 13 (3) | |

| 8–10 | 113 (12) | 53 (11) | 60 (13) | |

| 11–15 | 271 (29) | 146 (32) | 125 (27) | |

| 16–20 | 271 (29) | 134 (29) | 137 (29) | |

| 21–30 | 204 (22) | 101 (22) | 103 (22) | |

| ≥31 | 56 (6) | 23 (5) | 33 (7) | |

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≤2 cm | 404 (43) | 189 (41) | 215 (46) | 0.34 |

| > 2 cm | 515 (55) | 266 (58) | 249 (53) | |

| Unknown | 14 (2) | 7 (2) | 7 (1) | |

| Vessel invasion | ||||

| No | 444 (48) | 211 (46) | 233 (49) | 0.17 |

| Yes | 302 (32) | 163 (35) | 139 (30) | |

| Unknown | 187 (20) | 88 (19) | 99 (21) | |

| Surgery | ||||

| Mastectomy | 643 (69) | 329 (71) | 314 (67) | 0.13 |

| Breast conserving | 290 (31) | 133 (29) | 157 (33) | |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| CMF × 6 | 239 (26) | 125 (27) | 114 (24) | 0.71 |

| CMF × 6 + 3 | 238 (26) | 113 (24) | 125 (27) | |

| CMF × 3 | 225 (24) | 113 (24) | 112 (24) | |

| CMF × 3 + 3 | 231 (25) | 111 (24) | 120 (25) | |

ECS, extracapsular tumor spread.

results

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the 933 patients with ECS information. Results are shown for the overall patient sample and for those with and without ECS. ECS is strongly correlated with number of positive lymph nodes. Patients with ECS tended to have higher numbers of positive nodes (P < 0.0001). ECS was not significantly associated with any of the other risk factors considered (Table 1).

The median follow-up is 14 years, with a maximum follow-up of 20 years. A total of 139 local failures were observed. The numbers of axillary and supraclavicular failures were 30 and 77, respectively. For patients with and without ECS, the respective 10-year cumulative incidence rates were 14.6% and 11.6% for local failure, 4.1% and 2.1% for axillary failure, and 9.8% and 5.8% for supraclavicular failure. Most relapses were observed during the first 5 years of follow-up (72% of local, 80% of axillary, and 77% of supraclavicular failures).

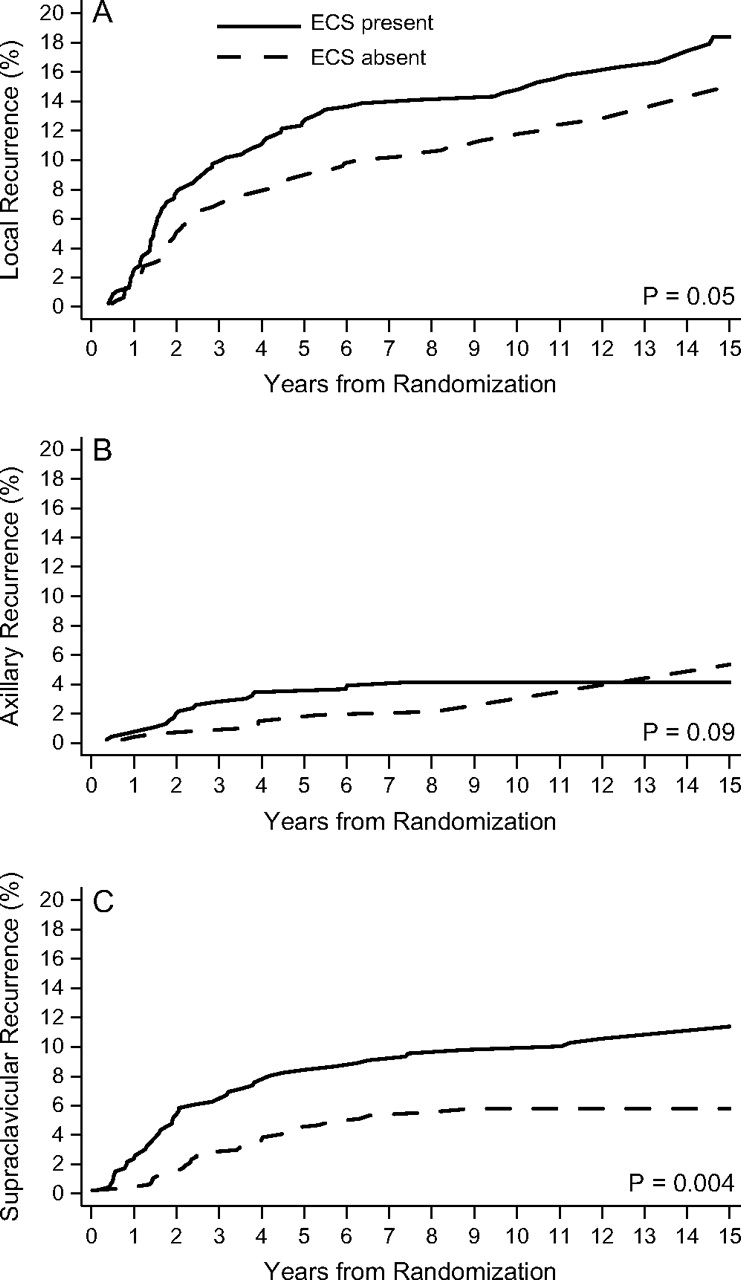

Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence of each failure type according to ECS status. For supraclavicular recurrences, the presence of ECS was associated with a higher cumulative incidence (P = 0.004). For local recurrences, ECS tended to be associated with higher cumulative incidence (P = 0.05). ECS was also moderately associated with higher cumulative incidence of axillary recurrence (P = 0.09).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence functions for 933 premenopausal patients with node-positive breast cancer randomized among four groups that differed according to duration and timing of classical combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil according to presence (solid line) or absence (dashed line) of extracapsular spread (ECS) for local recurrence (A), axillary recurrence (B), and supraclavicular recurrence (C).

Multivariable methods were used to evaluate the association between ECS and failure type after adjustment for all the other risk factors. Table 2 shows the hazard ratio (HR) for each type of recurrence derived from competing risks regression analysis without adjustment for any other risk factors. These results are consistent with those shown in Figure 1; however, the P values differ slightly because different test procedures were used. In particular, ECS is strongly and significantly associated with a higher risk for supraclavicular recurrences. It is moderately, though not statistically significantly, associated with the risk of local recurrence and the risk of axillary recurrence. After adjustment for all covariates, ECS was no longer a significant predictor (Table 2). Table 3 shows the HR estimates from the multivariable competing risks regression models for local, axillary, and supraclavicular recurrences, respectively. It is noteworthy that the type of local treatment (mastectomy versus BCS + RT) did not significantly influence the pattern of locoregional recurrence. After removal of nonsignificant predictors (except for ECS) using a backward elimination approach, the estimated HRs for ECS were similar to those shown in Table 3. Patients with ECS had a higher risk of local failure [adjusted HR = 1.22; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85–1.76]; however, it was not statistically significant (P = 0.28). Significant predictors for supraclavicular recurrence (Table 3) were adjuvant CMF treatment regimen and the number of positive lymph nodes. For axillary recurrences, no significant predictors were found.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratiosa for ECS relative to no ECS based on competing risks regression analysis

| Failure type | Unadjusted hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value | Adjusted hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value |

| Local | 1.38 | 0.99–1.94 | 0.06 | 1.22 | 0.85–1.76 | 0.28 |

| Axillary | 1.81 | 0.87–3.78 | 0.11 | 1.48 | 0.65–3.37 | 0.35 |

| Supraclavicular | 1.96 | 1.23–3.13 | 0.005 | 1.54 | 0.92–2.56 | 0.10 |

Hazard ratios are for ECS relative to no ECS and are based on competing risks regression analysis with the following adjustment factors: treatment group, age, estrogen-receptor status, number of positive nodes (1–3, ≥4), quartile of number of nodes examined, tumor size, vessel invasion and type of surgery.

ECS, extracapsular tumor spread.

Table 3.

Multivariable competing risks regression models for local, axillary and supraclavicular recurrence

| Predictor | Local recurrence |

Axillary recurrence |

Supraclavicular recurrence |

||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| ECS | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | — | 0.28 | 1.00 | — | 0.35 | 1.00 | — | 0.10 |

| Yes | 1.22 | 0.85–1.76 | 1.48 | 0.65–3.37 | 1.54 | 0.92–2.56 | |||

| Treatment group | |||||||||

| CMF × 6 | 1.00 | — | 0.35 | 1.00 | — | 0.35 | 1.00 | — | 0.05 |

| CMF × 6 + 3 | 0.78 | 0.47–1.30 | 0.63 | 0.24–1.67 | 1.66 | 0.85–3.25 | |||

| CMF × 3 | 1.24 | 0.79–1.92 | 0.36 | 0.12–1.12 | 2.07 | 1.09–3.91 | |||

| CMF × 3 + 3 | 0.96 | 0.60–1.53 | 0.72 | 0.28–1.83 | 0.97 | 0.46–2.07 | |||

| Age, years | |||||||||

| <40 | 1.00 | — | <0.0001 | 1.00 | — | 0.99 | 1.00 | — | 0.13 |

| 40+ | 0.46 | 0.32–0.67 | 0.99 | 0.39–2.54 | 0.66 | 0.38–1.13 | |||

| Estrogen receptor status | |||||||||

| Negative | 1.00 | — | 0.05 | 1.00 | — | 0.53 | 1.00 | — | 0.27 |

| Positive | 1.52 | 0.99–2.31 | 1.32 | 0.56–3.11 | 0.75 | 0.45–1.25 | |||

| Number of positive nodes | |||||||||

| 1–3 | 1.00 | — | 0.03 | 1.00 | — | 0.18 | 1.00 | — | 0.01 |

| 4+ | 1.52 | 1.05–2.19 | 1.76 | 0.78–4.00 | 1.94 | 1.15–3.25 | |||

| Number of nodes examined | |||||||||

| 1–11 | 1.00 | — | 0.009 | 1.00 | — | 0.68 | 1.00 | — | 0.41 |

| 12–15 | 0.50 | 0.30–0.82 | 1.07 | 0.36–3.18 | 1.09 | 0.58–2.05 | |||

| 16–20 | 0.74 | 0.47–1.16 | 1.10 | 0.40–3.03 | 0.67 | 0.33–1.36 | |||

| 21+ | 0.49 | 0.30–0.79 | 0.61 | 0.19–1.96 | 0.78 | 0.40–1.51 | |||

| Tumor sizea | |||||||||

| ≤2 cm | 1.00 | — | 0.39 | 1.00 | — | 0.52 | 1.00 | — | 0.17 |

| >2 cm | 1.24 | 0.85–1.82 | 1.35 | 0.55–3.29 | 1.68 | 0.97–2.91 | |||

| Unknown | 0.53 | 0.08–3.51 | — | — | 1.10 | 0.13–9.01 | |||

| Vessel invasion | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | — | 0.03 | 1.00 | — | 0.16 | 1.00 | — | 0.60 |

| Yes | 1.64 | 1.12–2.40 | 1.30 | 0.53–3.19 | 1.31 | 0.77–2.25 | |||

| Unknown | 1.46 | 0.93–2.29 | 2.38 | 0.98–5.78 | 1.19 | 0.64–2.22 | |||

| Surgery | |||||||||

| Breast conserving | 1.00 | — | 0.87 | 1.00 | — | 0.21 | 1.00 | — | 0.26 |

| Mastectomy | 0.97 | 0.65–1.43 | 1.89 | 0.69–5.19 | 0.74 | 0.43–1.26 | |||

For axillary recurrence, unknown tumor size was combined with ≤2 cm because of small numbers.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECS, extracapsular tumor spread.

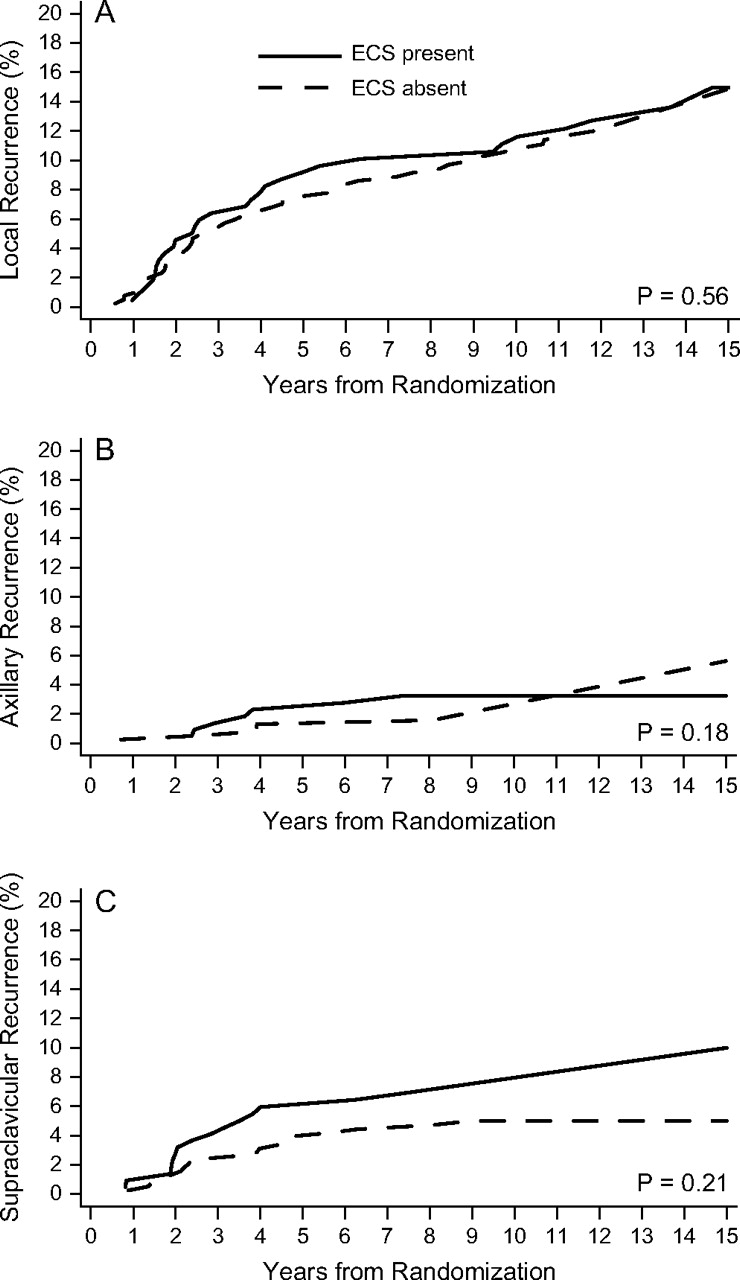

Analyses were also carried out on the subgroups of one to three and four or more positive lymph nodes (Table 4). Among patients with one to three positive nodes, ECS was present in 219 of 604 patients (36%) and was significantly associated with the number of positive lymph nodes. Eighty-four of 303 patients with one positive node (28%) were ECS positive versus 135 of 301 with two to three positive nodes (45%), P < 0.0001. For patients with and without ECS, the respective 10-year cumulative incidence rates were 11.1% and 10.5% for local failure, 3.2% and 1.6% for axillary failure, and 6.9% and 5.0% for supraclavicular failure. In this patient cohort, ECS was not statistically significantly associated with risk of local (unadjusted HR 1.13; 95% CI 0.71–1.80, P = 0.59), axillary (unadjusted HR 1.88; 95% CI 0.67–5.28, P = 0.23), and supraclavicular failure (unadjusted HR 1.52; 95% CI 0.78–2.96, P = 0.22). Cumulative incidence in this group of patients is shown in Figure 2.

Table 4.

10-Year cumulative incidence percent (standard error)

| Recurrence type | ECS | No ECS |

| All patients | ||

| Local | 14.6 (1.6) | 11.6 (1.5) |

| Axillary | 4.1 (0.9) | 2.1 (0.7) |

| Supraclavicular | 9.8 (1.4) | 5.8 (1.1) |

| Patients with one to three positive nodes | ||

| Local | 11.1 (2.1) | 10.5 (1.6) |

| Axillary | 3.2 (1.2) | 1.6 (0.6) |

| Supraclavicular | 6.9 (1.7) | 5.0 (1.1) |

| Patients with four or more positive nodes | ||

| Local | 17.7 (2.5) | 16.3 (4.0) |

| Axillary | 4.9 (1.4) | 4.7 (2.3) |

| Supraclavicular | 12.4 (2.1) | 9.3 (3.2) |

ECS, extracapsular tumor spread.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence functions for 604 premenopausal patients with one to three positive lymph nodes according to presence (solid line) or absence (dashed line) of extracapsular spread (ECS) for local recurrence (A), axillary recurrence (B), and supraclavicular recurrence (C).

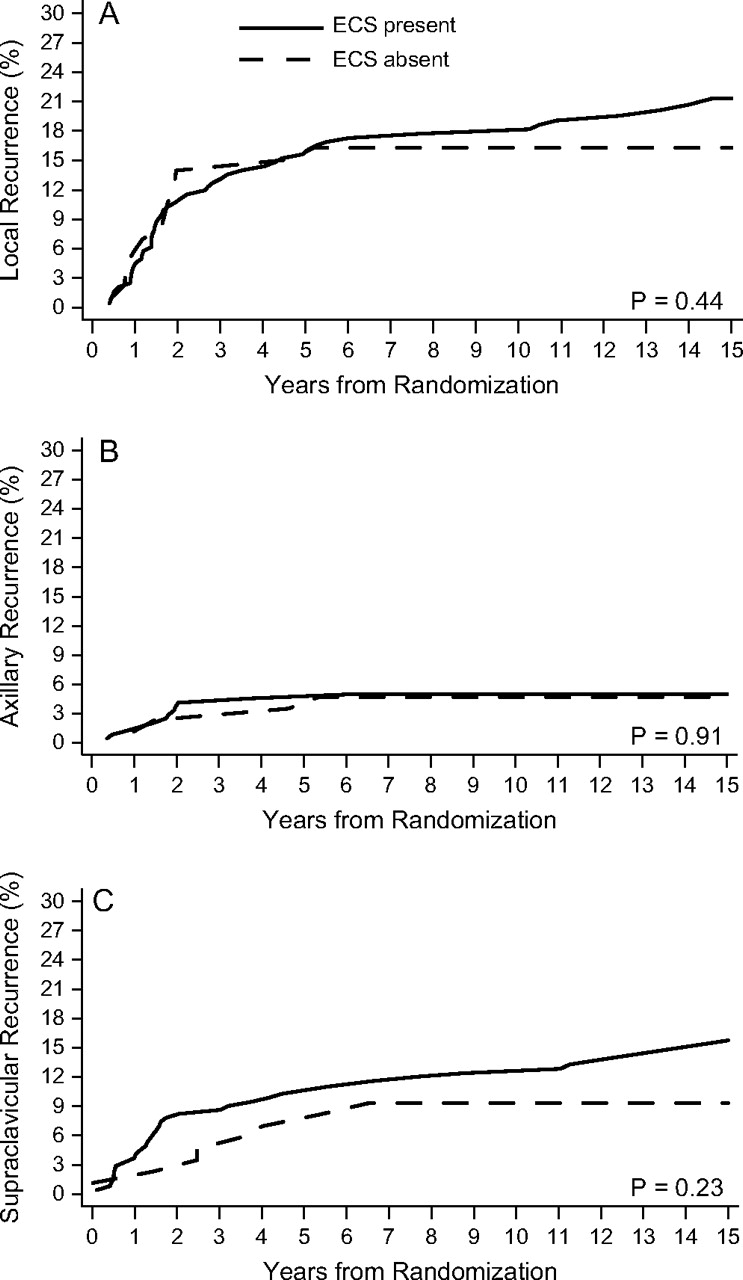

Among patients with four or more positive nodes, ECS was present in 243 of 329 patients (74%) and was significantly associated with the number of positive lymph nodes (data not shown). For patients with and without ECS, the respective 10-year cumulative incidence rates were 17.7% and 16.3% for local failure, 4.9% and 4.7% for axillary failure, and 12.4% and 9.3% for supraclavicular failure. In this patient cohort, ECS was not statistically significantly associated with risk of local (unadjusted HR 1.27; 95% CI 0.69–2.30, P = 0.44), axillary (unadjusted HR 1.07; 95% CI 0.35–3.29, P = 0.91) and supraclavicular failure (unadjusted HR 1.56; 95% CI 0.73–3.36, P = 0.25). Cumulative incidence in this group of patients is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence functions for 329 premenopausal patients with four or more positive lymph nodes according to presence (solid line) or absence (dashed line) of extracapsular spread (ECS) for local recurrence (A), axillary recurrence (B), and supraclavicular recurrence (C).

discussion

In the literature, ECS is documented in the range of 24%–60% of breast cancer cases [5, 6, 11–21]. Furthermore, in the era of the sentinel node (SN) technique, several studies have shown that the presence of ECS of the SN metastasis is a strong predictor of non-SN tumor involvement in the axilla [22, 23]. The likelihood of ECS rises with the number of positive lymph nodes [6], which makes determining an independent prognostic role difficult. The first reports showing an association of ECS with poorer outcome were published ∼30 years ago [24, 25] and were confirmed by almost every subsequent study [12–14, 17, 26–28], but not in all [15, 18]. The interpretation of these studies is difficult as they all differ in patient selection and the use of radiotherapy and systemic treatments. Katz et al. [5] retrospectively analyzed the impact of ECS in pre- and postmenopausal women with node-positive breast cancer treated with mastectomy and anthracycline-containing systemic therapies without radiotherapy in five randomized trials at the MD Anderson Cancer Center between 1975 and 1994. ECS with an extent of ≥2 mm was a significant predictor of increased risk of LRF in univariable and multivariable analyses, overall and in the subgroup of T1/T2 tumors with one to three positive nodes. Interestingly, patients with ‘ECS < 2 mm’ or ‘ECS not otherwise specified’ experienced similar LRF rates compared with patients without ECS [5]. In a previous report of our group encompassing the patient cohort of the current study, the impact of ECS was evaluated in regard to LRF overall, DFS and OS [6]. At 10 years, 14% [±2% (standard error)] of patients without ECS experienced LRF versus 18% (±2%) of patients with ECS. The corresponding rates for LRF with or without distant failure were 19% (±2%) versus 27% (±2%). These differences (DFS, OS, LRF, LRF with or without distant failure) were statistically significant in univariable analyses. However, the differences were no longer significant after adjusting for the number of positive nodes [6].

Due to the lack of information in the literature, the aim of the current analysis was to determine the relationship of ECS status and different sites of locoregional relapses. There is still controversy among radiation oncologists whether these patients may benefit from regional irradiation.

In general, axillary failure rates are low [29], and in the presence of ECS, 0%–5% of patients relapse in the axilla without axillary irradiation: 1/122 (0.8%) [15], 1/43 (2.3%) [26], 1/20 (5%) [13], 1/27 (3.7%) [17], and 0/6 (0%) [18]. As the lower part of the axillary region is often encompassed by the tangential chest/breast fields, series with no irradiation are more appropriate for failure rate definition, but even then axillary relapses were uncommon: 0/62 (0%) [27], 2/28 (7.1%) [26], 6/82 (7%) [11], 0/43 (0%) [28], 1/85 (1.2%) [19], and 5/293 (1.7%) [30]. In our study, we observed axillary failures in 4% of patients with ECS compared with 2% in the absence of ECS, which was of borderline statistical significance in univariable analysis. However, no independent role could be documented after adjustment for other risk factors. It is interesting to note that for axillary failure, no significant parameter could be found in multivariable analysis, which is consistent with a recent analysis from the MD Anderson Cancer Center [30]. After dissection of level I/II, axillary failure rates were low and irradiation of the axilla was not indicated. The presence of ECS did not modify the author's recommendation.

There is even less data concerning the association of ECS with supraclavicular failure. In the MD Anderson study, 20 of 142 patients with gross extranodal extension experienced periclavicular failure. The 10-year actuarial failure rate was 19%, whereas the corresponding numbers were 11% in the presence of focal ECS and 6% in its absence [30]. In subgroup analyses (one to three positive nodes, four or more positive nodes, T1/T2 and one to three positive nodes), the risk of periclavicular failure was still higher for patients with gross ECS, but none of these analyses was statistically significant. Nevertheless, the authors recommend radiation to undissected regions (supraclavicular fossa/axillary apex) in addition to the chest wall in patients with gross extranodal extension regardless of the number of positive lymph nodes [30]. Unfortunately, details about multivariable analyses were not given and patients with ECS not otherwise specified were pooled together with focal ECS [30].

We did not find a significant impact of ECS on supraclavicular failure overall and in the subgroups of patients with one to three or four or more positive nodes. We can, therefore, not support irradiation of the periclavicular region/axillary apex solely based on the finding of ECS. A limitation of the current report is that the extent of ECS (focal versus gross) was not reliably available in the pathology reports, and one cannot exclude that significant differences could be detected if analyses were restricted to gross ECS.

In conclusion, the current series reports by far the largest evaluation of ECS in premenopausal patients prospectively treated in one single randomized trial in which all patients received the same chemotherapeutic agents. We are unable to confirm an independent prognostic significance of ECS on local, axillary, or supraclavicular failure. The decision for additional regional radiotherapy should not be based solely on the presence of ECS.

funding

Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research; Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation; The Cancer Council Australia; Australian New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group; National Cancer Institute (CA-75362); Swedish Cancer Society; Cancer Association of South Africa; Foundation for Clinical Research of Eastern Switzerland; OncoSuisse/Cancer Research Switzerland.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients, physicians, nurses, and data managers who participate in the International Breast Cancer Study Group trials. We thank Rita Hinkle for data management. Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

Appendix of Participants in IBCSG Trial VI

| Scientific Committee | A. Goldhirsch, A.S. Coates (Co-Chairs) | |

| Foundation Council | R. Stahel (President), A. S. Coates, M. de Stoppani, R. D. Gelber, A. Goldhirsch, M. Green, A. Hiltbrunner, D. K. Hossfeld, P. Karlsson, I. Kössler, I. Láng, B. Thürlimann, A. Veronesi | |

| Coordinating Center, Bern, Switzerland | M. Castiglione (Study Chair), A. Hiltbrunner (Director); G. Egli, M. Rabaglio, R. Maibach, R. Studer, B. Ruepp, D. Bärtschi | |

| Statistical Center, Harvard School of Public Health and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA | R. Gelber (Group Statistician), K. Price, B. Cole, M. Regan, Z. Sun, S. Gelber, A. Giobbie-Hurder, M. Dasgupta, L. Nickerson | |

| Data Management Center, Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation, Amherst, NY, USA | L. Blacher (Director), R. Hinkle, J. Celano, T. Scolese | |

| Pathology Office | B. Gusterson, G. Viale, E. Mallon | |

| Centro di Riferimento Oncologico, Aviano, Italy | A. Veronesi, D. Crivellari, S. Monfardini, E. Galligioni, M. D. Magri, A. Buonadonna, S. Massarut, C. Rossi, E. Candiani, A. Carbone, R. Volpe, M. Roncadin, M. Arcicasa, F. Coran, S. Morassut | |

| Spedali Civili and Fondazione Beretta, Brescia, Italy | E. Simoncini, G. Marini, P. Marpicati, L. Lucini, P. Grigolato, L. Morassi, R. Farfaglia, A. M. Bianchi | |

| Groote Schuur Hospital and University of Cape Town, Republic of South Africa | E. Murray, D. M. Dent, A. Gudgeon, I. D. Werner, A. Hacking, A. Tiltman, E. McEvoy, J. Toop | |

| West Swedish Breast Cancer Study Group, Göteborg, Sweden | C. M. Rudenstam, S. B. Holmberg, P. Karlsson, A. Wallgren, S. Ottosson-Lönn, R. Hultborn, G. Colldahl-Jädeström, E. Cahlin, J. Mattsson, O. Ruusvik, L. G. Niklasson, S. Dahlin, G. Karlsson, B. Lindberg, A. Sundbäck, S. BergegÂrdh, O. Groot, L. O. Dahlbäck, H. Salander, C. Andersson, M. Heideman, A. Nissborg, A. Wallin, G. Claes, T. Ramhult, J. H. Svensson, P. Liedberg, A. Nilsson, G. Oestberg, S. Persson, J. Matusik | |

| The Institute of Oncology, Ljubljana, Slovenia | J. Lindtner, D. Erzen, T. Cufer, E. Majdic, B. Stabuc, R. Golouh, J. Lamovec, J. Jancar, I. Vrhovec, M. Kramberger, J. Novak, M. Naglas, M. Sencar, J. Cervek, S. Sebek, O. Cerar, A. Plesnicar, B. Zakotnik | |

| Madrid Breast Cancer Group, Madrid, Spain | H. Cortès-Funes, C. Mendiola, C. Gravalos, Colomer, M. Mendez, F. Cruz Vigo, P. Miranda, A. Sierra, F. Martinez-Tello, A. Garzon, S. Alonso, A. Ferrero, C. Vargas | |

| Australian New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group (ANZ BCTG) Operations Office, University of Newcastle | J. F. Forbes, D. Lindsay | |

| Statistical Center, NHMRC CTC, University of Sydney: | R. J. Simes, E. Beller, C. Stone, V. Gebski | |

| The Cancer Council Victoria (formerly Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria), Melbourne, Australia | J. Collins, R. Snyder, E. Abdi, R. Basser, R. Bennett, P. Briggs, P. Brodie, W. I. Burns, M. Chipman, J. Chirgwin, R. Drummond, P. Ellims, D. Finkelde, P. Francis, J. Funder, T. Gale, M. Green, P. Gregory, J. Griffiths, G. Goss, L. Harrison, S. Hart, M. Henderson, V. Humenuik, P. Jeal, P. Kitchen, G. Lindeman, B. Mann, J. McKendrick, R. McLennan, R. Millar, C. Murphy, S. Neil, I. Olver, M. Pitcher, A. Read, D. Reading, R. Reed, G. Richardson, A. Rodger, I. Russell, M. Schwarz, L. Sisely, R. Stanley, M. Steele, J. Stewart, C. Underhill, J. Zalcberg, A. Zimet | |

| Flinders Medical Centre, Bedford Park, South Australia | S. Birrell, M. Eaton, C. Hoffmann, B. Koczwara, C. Karapetis, T. Malden, W. McLeay, R. Seshadri | |

| Calgary Mater Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia, Gold Coast Hospital, Queensland, Australia | J. F. Forbes, J. Stewart, D. Jackson, R. Gourlay, J. Bishop, S. Cox, S. Ackland, A. Bonaventura, C. Hamilton, J. Denham, P. O'Brien, M. Back, S. Brae, A. Price, R. Muragasu, H. Foster, D. Clarke, R. Sillar, I. MacDonald, R. Hitchins | |

| Royal Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide, Australia | I. N. Olver, D. Keefe, M. Brown, P. G. Gill, A. Taylor, A. Robertson, P. G. Gill, M. L. Carter, P. Malycha, E. Yeoh, G. Ward, A. S. Y. Leong, J. Lommax-Smith, D. Horsfall, R. D'Angelo, E Abdi, J. Cleary, F. Parnis | |

| Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, Australia | E. Bayliss | |

| Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Nedlands, Western Australia | M. Byrne, G. van Hazel, J. Dewar, M. Buck, D. Ingram, G. Sterrett, P. M. Reynolds, H. J. Sheiner, K. B. Shilkin, R. Hahnel, S. Levitt, D. Kermode, H. Hahnel, D. Hastrich, D. Joseph, F. Cameron | |

| University of Sydney, Dubbo Base Hospital and Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia | M. H. N. Tattersall, A. Coates, F. Niesche, R. West, S. Renwick, J. Donovan, P. Duval, R. J. Simes, A. Ng, D. Glenn, R. A. North, J. Beith, R. G. O'Connor, M. Rice, G. Stevens, J. Grassby, S. Pendlebury, C. McLeod, M. Boyer, A. Sullivan, J. Hobbs, R. Fox, D. Hedley, D. Raghavan, D. Green, T. Foo, T. J. Nash, J. Grygiel, D. Lind | |

| Prince of Wales, Randwick, NSW, Australia | C. Lewis, M. Friedlander | |

| Auckland Breast Cancer Study Group, Auckland, New Zealand | R. G. Kay, I. M. Holdaway, V. J. Harvey, C. S. Benjamin, P. Thompson, A. Bierre, M. Miller, B. Hochstein, A. Lethaby, J. Webber, M. F. Jagusch, L. Neave, B. M. Mason, B. Evans, J. F. Carter, J. C. Gillman, D. Mack, D. Benson-Cooper, J. Probert, H. Wood, J. Anderson, L. Yee, G. C. Hitchcock, A. Lethaby, J. Webber, D. Porter | |

| Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand | I. Kennedy, G. Round, J. Long | |

| SAKK (Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research) | ||

| Inselspital, Bern, Switzerland | M. F. Fey, S. Aebi, M. Castiglione-Gertsch, E. Dreher, K. Buser, J. Ludin, G. Beck, J. M. Lüthi, H. J. Altermatt, M. Nandedkar | |

| Kantonsspital, St Gallen, Switzerland | H. J. Senn, B. Thürlimann, Ch. Oehlschlegel, G. Ries, M. Töpfer, U. Lorenz, A. Ehrsam, B. Späti, E. Vogel | |

| Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland Ospedale San Giovanni, Bellinzona, Switzerland | F. Cavalli, O. Pagani, H. Neuenschwander, C. Sessa, M. Ghielmini, E. Zucca, J. Bernier, E. S. Pedrinis, T. Rusca, E. Passega,, L. Bronz, P. Rey, M. Galfetti, W. Sanzeni, T. Gyr, L. Leidi, G. Pastorelli, M. Varini, S. Longhi, C. Cafaro-Greco, R. Graffeo, A. Goldhirsch | |

| Kantonsspital, Basel, Switzerland | R. Herrmann, C. F. Rochlitz, J. F. Harder, O. Köchli, U. Eppenberger, J. Torhorst | |

| Hôpital des Cadolles, Neuchâtel, Switzerland | D. Piguet, P. Siegenthaler, V. Barrelet, R.P. Baumann | |

| Kantonsspital, Zürich, Switzerland | B. Pestalozzi, C. Sauter, U. Haller, U. Metzger, P. Huguenin, R. Caduff | |

| Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Lausanne, Switzerland | L. Perey, K. Zaman, S. Leyvraz, P. De Grandi, W. Jeanneret-Sozzi, R. Mirimanoff, J. F. Delaloye | |

| Hôpital Cantonal, Geneva, Switzerland | M. Nobahar, P. Alberto, H. Bonnefoi, P. Schäfer, F. Krauer, M. Forni, M. Aapro, R. Egeli, R. Megevand, E. Jacot-des-Combes, A. Schindler, B. Borisch, S. Diebold | |

| Kantonsspital Graubünden, Chur, Switzerland | F. Egli, A. Willi, R. Steiner. J. Allemann, T. Rüedi, A. Leutenegger, U. Dalla Torre | |

References

- 1.Overgaard M, Hansen PS, Overgaard J, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in high-risk premenopausal women with breast cancer who receive adjuvant chemotherapy: Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group 82b Trial. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:949–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Overgaard M, Jensen MB, Overgaard J, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in high-risk postmenopausal breast-cancer patients given adjuvant tamoxifen: Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group DBCG 82c randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1641–1648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ragaz J, Jackson SM, Le N, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy in node-positive premenopausal women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:956–962. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ceilley E, Jagsi R, Goldberg S, et al. Radiotherapy for invasive breast cancer in North America and Europe: results of a survey. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz A, Strom EA, Buchholz TA, et al. Locoregional recurrence patterns after mastectomy and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy: implications for postoperative irradiation. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2817–2827. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.15.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruber G, Bonetti M, Nasi ML, et al. Prognostic value of extracapsular tumor spread for locoregional control in premenopausal patients with node-positive breast cancer treated with classical cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil: long-term observations from International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial VI. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7089–7097. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The International Breast Cancer Study Group. Duration and reintroduction of adjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive premenopausal breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1885–1894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox DR. Regression models and lifetables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher BJ, Perera FE, Cooke AL, et al. Extracapsular axillary node extension in patients receiving adjuvant systemic therapy: an indication for radiotherapy? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:551–559. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)89483-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahlert S, Boettcher B, Lebeau A, et al. Prognostic impact of extended extracapsular component in involved lymph nodes in primary breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:S89. Abstr 292. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonard C, Corkill M, Tomkin J, et al. Are axillary recurrence and overall survival affected by axillary extranodal tumor extension in breast cancer? Implications for radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:47–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ragaz J, Jackson S, Le N, et al. Postmastectomy radiation outcome in node positive breast cancer patients among N1–3 versus N4+ subset: Impact of extracapsular spread—update of the British Columbia Randomized Trial. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1999;18:73a. Abstr 274. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hetelekidis S, Schnitt SJ, Silver B, et al. The significance of extracapsular extension of axillary lymph node metastases in early-stage breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:31–34. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veronesi U, Rilke F, Luini A, et al. Distribution of axillary node metastases by level of invasion: an analysis of 539 cases. Cancer. 1987;59:682–687. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870215)59:4<682::aid-cncr2820590403>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierce LJ, Oberman HA, Strawderman MH, et al. Microscopic extracapsular extension in the axilla: is this an indication for axillary radiotherapy? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33:253–259. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vicini FA, Horwitz EM, Lacerna MD, et al. The role of regional nodal irradiation in the management of patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 199739:1069–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00555-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fodor J, Toth J, Major T, et al. Incidence and time of occurrence of regional recurrence in stage I–II breast cancer: value of adjuvant irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44:281–287. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jager JJ, Volovics L, Schouten LJ, et al. Loco-regional recurrences after mastectomy in breast cancer: prognostic factors and implications for postoperative irradiation. Radiother Oncol. 1999;50:267–275. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(98)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gruber G, Menzi S, Forster A, et al. Sites of failure in breast cancer patients with extracapsular invasion of axillary lymph node metastases no need for axillary irradiation?! Strahenther Onkol. 2005;181:574–579. doi: 10.1007/s00066-005-1367-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stitzenberg KB, Meyer AA, Stern SL, et al. Extracapsular extension of the sentinel lymph node metastasis: a predictor of nonsentinel node tumor burden. Ann Surg. 2003;237:607–612. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000064361.12265.9A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapur U, Rubinas T, Ghai R, et al. Prediction of nonsentinel lymph node metastasis in sentinel node-positive breast carcinoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2007;11:10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher ER, Palekar AS, Gregorio RM, et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (protocol No. 4), III: the significance of extranodal extension of axillary metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976;65:439–444. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/65.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mambo NC, Gallager S. Carcinoma of the breast: the prognostic significance of extranodal extension of axillary disease. Cancer. 1977;39:2280–2285. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197705)39:5<2280::aid-cncr2820390548>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bucci JA, Kennedy CW, Burn J, et al. Implications of extranodal spread in node positive breast cancer: a review of survival and local recurrence. Breast. 2001;10:213–219. doi: 10.1054/brst.2000.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donegan WL, Stine SB, Samter TG. Implications of extracapsular nodal metastases for treatment and prognosis of breast cancer. Cancer. 1993;72:778–782. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930801)72:3<778::aid-cncr2820720324>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mignano JE, Zahurak ML, Chakravarthy A, et al. Significance of axillary lymph node extranodal soft tissue extension and indications for postmastectomy irradiation. Cancer. 1999;86:1258–1262. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991001)86:7<1258::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallgren A, Bonetti M, Gelber RD, et al. Risk factors for locoregional recurrence among breast cancer patients: results from International Breast Cancer Study Group trials I through VII. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1205–1213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strom EA, Woodward WA, Katz A, et al. Clinical Investigation: regional nodal failure patterns in breast cancer patients treated with mastectomy without radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:1508–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]