Abstract

Objective

“Teachable moments” have been proposed as events or circumstances which can lead individuals to positive behavior change. However, the essential elements of teachable moments have not been elucidated. Therefore, we undertook a comprehensive review of the literature to uncover common definitions and key elements of this phenomenon.

Methods

Using databases spanning social science and medical disciplines, all records containing the search term “teachable moment*” were collected. Identified literature was then systematically reviewed and patterns were derived.

Results

Across disciplines, ‘teachable moment’ has been poorly developed both conceptually and operationally. Usage of the term falls into three categories: 1) “teachable moment” is synonymous with “opportunity” (81%); 2) a context that leads to a higher than expected behavior change is retrospectively labeled a ‘teachable moment’ (17%); 3) a phenomenon that involves a cueing event that prompts specific cognitive and emotional responses (2%).

Conclusion

The findings suggest that the teachable moment is not necessarily unpredictable or simply a convergence of situational factors that prompt behavior change but suggest the possible creation of a teachable moment through clinician-patient interaction.

Practice Implications

Clinician-patient interaction may be central to the creation of teachable moments for health behavior change.

Keywords: teachable moment, health behavior, motivation, smoking cessation

1. Introduction

A large body of health care research and practice has been focused on the various strategies and contexts by which healthy behaviors can be promoted and unhealthy behaviors can be discouraged. One such strategy is the “teachable moment.” Teachable moments have been advocated for promoting health behavior change in a variety of settings.(1–12) Often described as a particular event or set of circumstances which leads individuals to alter their health behavior positively, the teachable moment has been intuitively accepted as an important focus for both clinicians and researchers interested in promoting health and wellness.(7, 10, 13, 14) However, empirical support for the effectiveness of health interventions based on the teachable moment is noticeably absent.(3) Moreover, the teachable moment for health behavior change is inadequately developed as a concept and is therefore unlikely to form a solid foundation for either research or practice.(15) Given the limitations of current health science research on the teachable moment concept, we cast a very broad net to examine potential insights from a range of disciplines. We systematically investigated the uses, descriptions and theoretical underpinnings of the teachable moment across a range of scholarly disciplines in order to explore the essential elements and evidence-base for this phenomenon.

2. Methods

Using databases covering a variety of scholarly fields, records containing the search term “teachable moment*” in any of the records’ fields were collected. All years contained in the following databases were searched: AltHealth Watch, AltaReligion, Business Premier, CINAHL, Communication and Mass Media Complete, ERIC, Professional Development Collection, PsychInfo, PubMed, Social Sciences Index, Social Work Abstracts, SocIndex, and Sociological Abstracts. Articles from non-English journals were excluded. Results were stratified into numbered lists according to their source database, and a sample of 20% of each stratum was selected using a random number generator. For databases with fewer than 10 records, all records were included in the final sample. A total of 404 articles were identified; 93 unique references were randomly selected, and 81 articles were successfully retrieved for review. Each article was read and reviewed for all uses of the term “teachable moments.” An annotated bibliography was created for each reference that consisted of an abstract for the article, a description of how the term “teachable moment” was used within the article, and complete text and citation for all uses of the term “teachable moment.” Uses of the term ‘teachable moment’ were categorized through repeated reading, sorting and identification of common usage patterns. Emergent categories were discussed by the authors and final descriptive criteria were derived for each category. All articles were sorted into these categories by the first author, and were then independently re-sorted by the second author. A very high level of inter-rater reliability was achieved, kappa =0.92.

3. Results

While the use of the teachable moment concept is widespread across a variety of scholarly disciplines and can be found frequently in popular media, its usage is far from standardized. Our extensive review of the literature revealed three categories into which the majority of usages fell. Table 1 provides a description of each category, the frequency of use and examples of each category type. In the first category, the term teachable moment is used more or less synonymously with the term opportunity. Of the 81 articles retrieved and reviewed, 66 fell into this category.(1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 11, 14, 16–45) (46–73) In the second category, the teachable moment is suggested as a particular context or event that is associated with a greater likelihood of the preferred outcome. Fourteen of the 81 articles reviewed describe the teachable moment in this way.(3, 5, 7, 9, 12, 13, 74–81) The third and least frequent usage suggests essential elements of the teachable moment and further offers theoretical models for its behavior changing effects. Only one article (82) discussed the teachable moment to this extent. In order to locate additional examples of this type of usage all 85 references from the PubMed database were reviewed, as were the references cited from all previously reviewed articles; one additional reference (83) was identified and included in this category.

Table 1.

Categories of usage for the term “teachable moment”

| Category Definition | n (%) | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Category 1 Teachable moment is an opportunity |

||

| The teachable moment is used to mean ‘opportunity’ or a particularly useful time to facilitate some sort of change. The concept use borders on self-evident truism. |

66 (81%) | “Here is your teachable moment—your opportunity to talk about the importance of parental role modeling as a tool for teaching children and the potential he and his wife have for sustaining a life-altering head injury” (Lassman 2001:172). |

| “So, the hoax offers a teachable moment—a chance to remind readers, viewers and listeners that not all information is journalism” (Cross 2005:18). |

||

| Category 2 Teachable moment as specific events or contexts |

||

| The teachable moment is a particularly useful time to facilitate some sort of change. Evidence is proffered whereby a teachable moment is retrospectively inferred because of a greater rate of behavior change associated with a context or situation. Mechanisms by which change may be enhanced during that time might be described. It is often suggested as the time to implement some from of intervention. |

14 (17%) | “Stone and colleagues demonstrated that coupling education about a “less effective” intervention while a patient underwent a more accepted one produced positive effects. So acceptance of a less desired, yet proved, intervention may be improved if coupled with education around a better accepted one, an event often referred to as a ‘teachable moment’” (Carlos et al 2005:221). |

| “These data suggest that providing health behavior advice during an illness visit for which a diagnosis relevant to the target behavior is present is associated with a 2- to 4-fold increase in the recall of the discussion, independent of the duration of the advice. Thus, choosing ‘teachable moments’ that link health behavior to current illnesses takes advantage of a unique opportunity for linking illness care with promoting healthy behavior” (Flocke and Stange 2004:346). |

||

| Category 3 Modeling the teachable moment |

||

| The teachable moment is a particularly useful time to facilitate some sort of change. This group goes beyond evidence provided in Category 2 and presents a theory of how the teachable moment operates to motivate an individual. Hypotheses are proposed, but are not tested. |

2 (2%) | “Cancer diagnosis and the cascade of associated events and interactions with the healthcare system have been described as “teachable moments” (TMs) for smoking cessation. Our work suggests that whether a cueing event such as a cancer diagnosis is significant enough to be a TM for smoking cessation depends on the extent to which the event: (1) increases perceptions of personal risk and related expectations of positive or negative outcomes, (2) prompts a strong emotional response, and (3) redefines self-concept or social role” (McBride and Ostroff 2003:330). |

3.1 Teachable Moment is an Unpredictable Opportunity

In the first usage, the term “teachable moment” is used to mean “opportunity,” and the concept is treated as a self-evident truism bordering on cliché or tautology. Here the teachable moment is an opportune moment for instruction and/or learning, but the psychological, or social interactional mechanisms by which it can be differentiated from any other moment are not acknowledged. In sources where this type of colloquial usage was prominent, a number of key patterns were noted. In many usages of this type, the teachable moment is a serendipitous event or constellation of factors that are regrettably unpredictable and therefore cannot be counted upon to facilitate learning or teaching.(44)

The spontaneity of teachable moments is also highlighted in discussions which draw attention to educators’ and counselors’ need for preparation or support to exploit the teachable moment effectively. Stubblefield suggests that, for a teachable moment to be successfully utilized, additional assistance or resources may be required, and in the absence of appropriate assistance, the teachable moment may not lead to a successful outcome. Stubblefield (69) states “For a person to move forward at a teachable moment requires a support system” (p. 240). Similarly, Fabiano suggests preparation, supervision and support for peer-health educators so that they can “deal effectively with these unexpected and fortuitous ‘teachable moments’ when their peers seek them out for assessment of risk for HIV” (p. 297).(29) In this example, both the spontaneity of the teachable moment and its need for support are articulated, although the nature of the support is not clear.

Not surprisingly, a number of authors suggest preparing teachers and other professionals to capitalize on the surprising situation of the teachable moment when it arises. Baker suggests that preparing faculty in business management programs to open dialog more ably around potentially challenging topics can allow them to take advantage of teachable moments when they occur in the classroom.(16) Brick argues for training teachers to respond effectively to the questions and behaviors of students that create teachable moments in classroom.(4) Other authors suggest that the unpredictability of the teachable moment is something that can be overcome through the implementation of specific curricular activities. In an essay on health education in the classroom, Kittleson describes a suicide prevention program that seeks to create a teachable moment in the classroom.(44) Nagoshi argues for the use of standardized patients in the training of physicians stating, “[Standardized patients] allow ‘teachable moments’ to be created, rather than waited for” (p. 323).(53) These authors implicitly construct the teachable moment as an effective technique for teaching and learning by arguing that it could and should actively be created. However, the mechanisms or ways in which a teachable moment could be actively created are not well articulated.

3.2 Teachable Moments as Specific Events or Contexts

In a second usage common in our literature search, the teachable moment is a specific event or context marked by an increased capacity for some sort of change. Fonarow(8) asserts that hospitalization for a cardiac event is a teachable moment that physicians should use to begin statin therapy. Carlos and Fendrick(5) argue that currently accepted screening procedures are teachable moments that can be used as vehicles to promote other, less-accepted, screening procedures. Similarly, Esler and Bock(6) assert that patients visiting the emergency department for non-cardiac chest pain are more likely to be motivated to make health behavior changes for stress reduction “during key times when their attention is focused on their health” (p. 267). Often, this second type of teachable moment is identified as a deviation from an expected outcome. Glasgow et al(13) demonstrate that smoking cessation occurs at a statistically higher rate among those smokers who had been hospitalized than would be predicted among the general population. From this, the authors conclude “hospitalization presents a teachable moment and an opportune setting in which to prompt cessation” (p. 32).(13)

In many cases in which deviations are presented as evidence for possible teachable moments, authors speculate about specific aspects of the context that may produce the observed anomaly. Flocke and Stange(7) assert that teachable moments may occur during visits with primary care doctors when a potential health behavior change is made more salient by a related illness. They report that patients are twice as likely to recall health behavior advice in the presence of a behavior related illness.(7) This is also suggested by Glasgow who proposes that hospitalization creates a temporary disruption in smoking behavior and represents a “window of opportunity” (p. 29) for deploying interventions that promote permanent cessation.(13) After an analysis of sustained weight loss, Gorin et al. conclude that medical triggers might enhance motivation to succeed in weight loss by increasing the saliency of the risks posed by obesity.(9) While all of the articles in this category suggested factors that may indeed be contributors to the phenomenon of a teachable moment, none explicitly tested or provided detailed discussions of those factors.

3.3 Modeling the Teachable Moment

The third and least frequent usage attempts to specify essential elements of the teachable moment and suggest theoretical models for its effects on behavior change. Only one article in our random sample contained any significant discussion of the mechanisms by which the teachable moment might have an impact on behavior or learning.(82) A more exhaustive search of all other references in our sample uncovered one additional article.(83) McBride and Ostroff argue that cancer diagnosis and treatment can be an important teachable moment for smoking cessation for both patients with cancer and their families.(82) In a more complete elaboration of their model of a teachable moment, McBride, Emmons and Lipkus assert that a cueing event is considered a teachable moment for smoking cessation insofar as it a) increases perceptions of risk and positive or negative outcome expectations, b) produces a strong emotional response, and c) causes a redefinition of an individual’s self-concept or social role.(83) This conception of the teachable moment relies significantly on the Health Belief Model(84) which emphasizes ‘cues to action,’ which influence the perceived threat of a negative outcome and may prompt an alteration of health behavior. Furthermore, the model for the teachable moment proposed by McBride, Emmons and Lipkus(85) also integrates aspects of Social Cognitive Theory(86) by focusing attention on the ways teachable moments might alter an individual’s expectancies and judgments about the outcome of a particular behavior on their health. They also suggest that events with strong emotional components (negative or positive) will result in those events becoming more significant and meaningful to an individual and will therefore be more likely to be teachable moments for health behavior change. Finally, the authors argue that teachable moments are more likely to arise when life events alter an individual’s self-concept or when individuals experience a change in their social role.(85) These new normative role obligations may be incompatible with current behavior. Thus, McBride et al. point to a cueing event with particular characteristics as the essential element of a teachable moment.(85)

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Discussion

Theorizing those aspects of the teachable moment that may cause behavior change is an important step in developing the utility of the teachable moment for research and intervention. Yet more is required. Barnett et al. (3) argue that there is insufficient evidence to determine whether or not particular events promote greater change among patients, whether interventions undertaken at those times produce greater change, or whether interventions implemented at such times would be as effective if undertaken at some other time. These empirical questions about the relationship between triggering events and possible outcomes remain uninvestigated. Despite a roadmap of recommendations for the study of the cognitive concepts proposed by the teachable moment model of McBride et al.,(85) little work has been reported.(87) Both observational and interventional research could advance our understanding of the teachable moment phenomenon and the impact it has on prompting behavior change.

The primary insight gained from this cross-disciplinary examination of literature is that the teachable moment phenomenon is not necessarily unpredictable or a simple convergence of contextual factors that prompt behavior change. A teachable moment could be created. More importantly, a teachable moment could be viewed as an event that is co-created through interaction. This is particularly relevant for dynamic and socially constructed interactions like medical encounters where the contents of that encounter ultimately depend on clinician and patient communication actions.(88) Moreover, these communication actions are shaped jointly by the goals, perceptions, knowledge and emotions of both interactants in response to each other.(88–91)

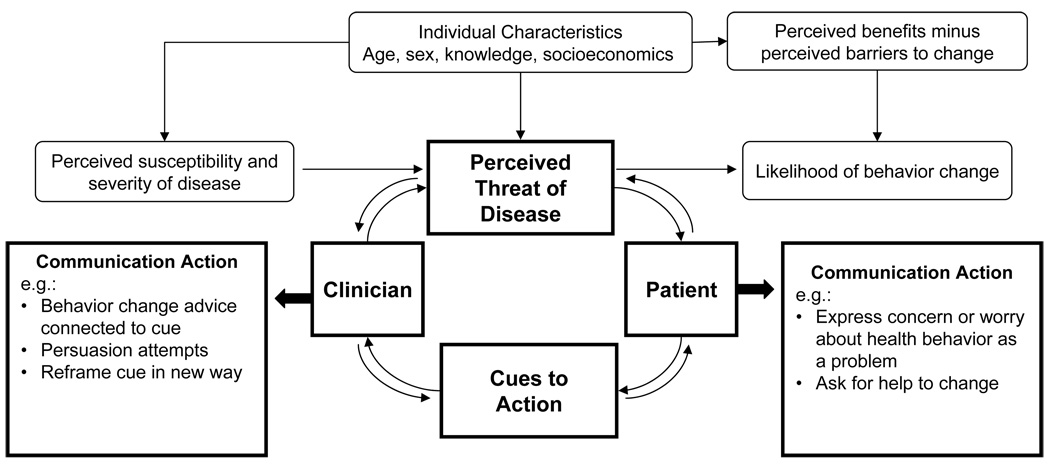

Conceptualizing a teachable moment as something that is created through interaction opens several new avenues for investigation. Prior work has focused on the influence of the sentinel event on patient perceptions or change. An interaction-based framework allows for the clinician’s perceptions, cognitions and motivations to be influenced by cues to action, as well. Thus, the components of the Health Belief Model: a cue to action, an increase in the perceived threat of disease for the patient, a belief in the significant benefit of behavior change for the patient, or a perception that barriers to change may be low for the patient, can also prompt role-specific action in the form of communication from the clinician. Figure 1 depicts an elaboration of the Health Belief Model which proposes that cues to action, perceived threat and benefit, and communication action can affect and be affected by both clinician and patient. Within this framework, communication actions such as: a clinician’s suggestion of a health behavior change as an effective therapy for a specific condition, the presentation of a worrisome symptom or test result potentially related to a patient’s unhealthy behavior, or a patient’s expression of difficulty in making or sustaining a health behavior change, could shape the perception of threat, benefit, or barriers to change for both the patient and clinician. Furthermore, this proposed framework highlights the potential for the co-creation of a teachable moment through clinician-patient communication as cues to action are generated and acted upon interactively.

Figure 1.

Elaboration of the Health Belief Model: A Dynamic Interaction of Cues to Action and Perceived Threat during Clinician and Patient Interaction

For example, a patient presenting with a severe flare-up of asthma could increase the clinician’s perception of the threat posed by the patient’s tobacco smoking. The clinician may communicate the potential lethality of severe asthma for the patient thereby raising the patient’s perception of the threat. Additionally, the clinician may highlight the potential benefit of smoking cessation for recovering from this acute episode and for avoiding future episodes. Seen this way, the relationship of perceived threat and benefit may affect how the health behavior is portrayed by the clinician and thus may affect the content and the intensity of persuasion for change that occurs during subsequent discussions of health behavior change. The frequency and types of cues present during typical encounters, if and how those cues are used by clinicians and patients to prompt discussion of health behavior change, and the effect of this communication on the likelihood of patient health behavior change are important areas for future research to illuminate the teachable moment.

Finally, it is important to recognize that clinician-patient communication during medical encounters is not co-constructed solely within an isolated, interpersonal interaction. Other systemic features such as the particulars of the medical practice setting, the organization of the local, regional and national health care system and the broad range of cultural experiences and expectations of the interactants will shape the communication as well.(88) Thus, examining the communication actions of clinicians and patients while attending to the salient contextual features that might impede or facilitate the construction of a teachable moment during a medical encounter is a worthwhile goal.

4.2 Conclusion

Though widely used across a variety of scholarly disciplines, the concept of the teachable moment remains largely untested and under-theorized. Research to date has predominately focused on the retrospective identification of circumstances associated with an increased likelihood of health behavior change. Examining how a teachable moment is created interactionally is ripe for investigation and likely to advance understanding of this phenomenon.

4.3 Practice Implications

Next steps should focus on the development of a model of the communication elements of a teachable moment for health behavior change. Understanding phenomena created through interaction and communication is best accomplished by analyzing audio and video-recorded clinician-patient interactions and pairing these analyses with data on subsequent patient outcomes. Although time and resource intensive, analyses of clinician-patient communication data could elucidate how a teachable moment occurs naturally in interaction and identify the contextual factors that enhance or impede the approach. Development of an interaction-based model could guide further research evaluating the feasibility of the teachable moment across practice settings and the effect on behavior change outcomes, and could guide clinician training.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the Case Department of Family Medicine writing workgroup and particularly Mary Step, PhD and David Litaker, MD, PhD for the valuable feedback at various stages of writing this manuscript.

Role of Funding

This study was funded by a research grant to Susan Flocke by the National Cancer Institute(#R01 CA 105292). The funding source had no involvement in the study design, or the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; nor did it affect the writing of the report or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

Neither author has any actual or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence, or be perceived to influence, this work.

References

- 1.Health observances create 'teachable moment': take advantage of heightened public awareness. Patient Educ Manag. 2000;7:18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson S. From early pregnancy through the postpartum year. Extending the teachable moment. Stanford Nurse. 1994;16:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett NP, Lebeau-Craven R, O'Leary TA, Colby SM, Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Woolard R, Spirito A. Predictors of motivation to change after medical treatment for drinking-related events in adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. 2002;16:106–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brick P. Fostering positive sexuality. Educ Leader. 1991;49:51–53. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlos RC, Fendrick AM. Improving cancer screening adherence: using the "teachable moment" as a delivery setting for educational interventions. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:247–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esler JL, Bock BC. Psychological treatments for noncardiac chest pain: recommendations for a new approach. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:263–269. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flocke SA, Stange KC. Direct observation and patient recall of health behavior advice. Prev Med. 2004;38:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonarow GC. In-hospital initiation of statins: taking advantage of the 'teachable moment'. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70(502):504–506. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.70.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorin AA, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Medical triggers are associated with better short-and long-term weight loss outcomes. Prev Med. 2004;39:612–616. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Having K. Obstetrical sonography: opportunities for "teachable moments" in patient care. J Diagn Med Sonog. 2000;16:242–243. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens VJ, Severson R, Lichtenstein E, Little SJ, Leben J. Making the most of a teachable moment: a smokeless-tobacco cessation intervention in the dental office. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:231. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winickoff J, Hillis V, Palfrey J, Perrin J, Rigotti N. A smoking cessation intervention for parents of children who are hospitalized for respiratory illness: the stop tobacco outreach program. Pediatrics. 2003;111:140–145. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glasgow RE, Stevens VJ, Vogt TM, Mullooly JP, et al. Changes in smoking associated with hospitalization: Quit rates, predictive variables, and intervention implications. Am J Health Promotion. 1991;6:24–29. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hotelling BA. Promoting wellness in lamaze classes. J Perinatal Ed. 2005;14:45–50. doi: 10.1624/105812405X57589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers B, Knafl K. Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker AC. Seizing the moment: talking about the 'undiscussables'. J Management Ed. 2004;28:693–706. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bentley ML. Making the most of the teachable moment: carpe diem. Sci Activit. 1995;32:23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boss S. Teachable moments: for the very young, art opens up a universe of learning. NW Educ. 1999;4:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowling JR. Clinical teaching in the ambulatory care setting: how to capture the teachable moment. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1993;93:235–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Briggs D. Turning conflicts into learning experiences. Educ Leader. 1996;54:60–63. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broughton K, Hunker S, Singer C. Internet Reference Services Q. Vol. 6. 2001. Why use web contact center software for digital reference? pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlson T. The sharing period in first grade. Elementary English. 1966;43:612. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caswell J. (Over) protecting students on campus? Educ Rec. 1991;72:20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chappelle S, Bigman L. Diversity in action. Zip Lines: The Voice for Adventure Education. 1998:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cross A. Journalists, entertainers becoming harder to decipher. Quill. 2005;93:18. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daniels HM. This teachable moment. Reformed Liturgy & Music. 1990;24:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dettlaff AJ, Dietz TJ. Making training relevant: identifying field instructors' perceived training needs (English) Clinical Supervisor. 2004;23:15–32. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dubney LC. Working with the elderly: a one-year internship training progam Combining practice and theory. J Applied Gerontology. 1990;9:118–128. doi: 10.1177/073346489000900110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fabiano P. Peer-based HIV risk assessment: a step-by-step guide through the teachable moment. J Am College Health. 1993;41:297–299. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1993.9936352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenenga MG. We did it this way. Marriage Fam Living. 1961;23:402. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freeman E. Families: teachable moments in school-community practice. Soc Work Educ. 1994;16:139–141. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonya J. Increasing your mathematics and science content knowledge. ENC Focus. 2002;9:46–47. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalez-Espada WJ, Bryan LA, Kang N-H. The intriguing physics inside an igloo. Phys Educ. 2001;36:290–292. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grandinetti D. For these doctors and patients, health means `personal best. '. Med Econ. 1998;75:82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guensburg C. Bully factories? Am Journalism Rev. 2001;23:50. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gunsauley C. Down market provides 'teachable' moments. Employee Benefit News. 2001;15:43. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanson VD. 'Teachable Moments'. National Review. 57:17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Havice A, Clark J. A preliminary survey of health education in Indiana home schools. J School Health. 2003;73:300–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2003.tb06586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hedlund R. Non-traditional team sports--taking full advantage of the teachable moment. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance. 1990;61:76–79. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herman BD. Teacher to teacher. Int J Childbirth Educ. 1990;5:31. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen JW. Dissertation. Utah: 1998. Apr 15, Supervision from six theoretical frameworks. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones L. Clinical vignettes. J of Supervision and Training in Ministry. 1989;11:140–149. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karpiak IE. Beyond competence: continuing education and the evolving self. The Social Worker. 1992;60:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kittleson MJ. Creating a teachable moment in suicide prevention. J Health Educ. 1994;25:110–111. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krueger M. Themes and stories in youthwork practice. Child Youth Serv. 2004;26:xi–93. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lassman J. Teachable moments: a paradigm shift. J Emerg Nurs. 2001;27:171–175. doi: 10.1067/men.2001.113190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lerner M. A teachable moment. Noetic Sciences Review. 2003:6. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Letts N. What do we mean by bad behavior? Teaching PreK-8. 1995;25:60–61. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loeb PR. Kids who care. Parents. 1999;74:104. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marshack EF, Hendricks CO, Gladstein M. The commonality of difference: teaching about diversity in field instruction. J Multicult Soc Work. 1994;3:77–89. [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGuinness T, Lowe D. Facilitating stress management and exercise: suggestions for acute care nurse practitioners and their patients. Nurse Pract Forum. 2001;12:151–154. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller S. Students as agents of classroom change: the power of cultivating positive expectations. J Adolesc Adult Lit. 2005;48:540–546. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nagoshi MH. Role of standardized patients in medical education. Hawaii Med J. 2001;60:323–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nathanson JP. Special Education Services: Outdoor Learning Program for Children with Handicapping Conditions. Kings Park, NY: SCOPE Outdoor Learning Laboratories/BOCES; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nutting PA. Health promotion in primary medical care: problems and potential. Prev Med. 1986;15:537–548. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O'Brien MP. From the editor. Int J Childbirth Educ. 1991;6:2. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palazzo MO. Teaching in crisis. Patient and family education in critical care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2001;13:83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parrott R. Emphasizing "communication" in health communication. J Comm. 2004;54:751–787. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perkin S. Access to books. Natural Life. 1996:20. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Piercy FP, Fontes LA. Teaching ethical decision-making in qualitative research: a learning activity. J Syst Ther. 2001;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reilly K. Ghost games. Coach & Athletic Director. 1998;68:24. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rich M. For a child, every moment is a teachable moment. Pediatrics. 2001;108:179–180. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roth W-M, Lawless DV, Masciotra D. Spielraumand teaching. Curriculum Inq. 2001;31:183. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Russo CJ. Prayer at public school graduation ceremonies: An exercise in futility or a teachable moment? Brigham Young University Education & Law Journal. 1999:1. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salpeter J. Tech forum highlights. Tech Learn. 2005;25:1. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scollay S, Logan JP. The gender equity role of educational administration: where are we? Where do we want to go? J School Lead. 1999;9:97–124. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Silk H, Agresta T, Weber CM. A new way to integrate clinically relevant technology into small-group teaching. Acad Med. 2006;81:239–244. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Fortess EE, Walser BL. Determinants of change in Medicaid pharmaceutical cost sharing: does evidence affect policy? Milbank Q. 1997;75:11–34. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stubblefield JM. An adult teachable moment. In: Stubblefield JM, editor. A church ministering to adults. Nashville, TN: Broadman Press; 1986. pp. 239–255. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tholen EJ. Home Energy Conservation Education. 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tibbetts J, Keeton P. Transitions are here. Is adult education ready? Adult Learning. 993;4:7. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wass H, Corr CA. Childhood and death. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Young JR. A 'Teachable Moment'. Chron High Educ. 2003;50:A30. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carlos RC, Underwood W, 3rd, Fendrick AM, Bernstein SJ. Behavioral associations between prostate and colon cancer screening. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Greene J. Forced abstinence and the 'teachable moment': hospitalization provides a good opportunity to encourage smokers to quit. Hosp Health Netw. 2003;77:30–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gritz ER, Fingeret MC, Vidrine DJ, Lazev AB, Mehta NV, Reece GP. Successes and failures of the teachable moment: smoking cessation in cancer patients. Cancer. 2006;106:17–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kolbe J. The influence of socioeconomic and psychological factors on patient adherence to self-management strategies: lessons learned in asthma. Disease Management & Health Outcomes. 2002;10:551–570. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lando HA. Reflections on 30+ years of smoking cessation research: from the individual to the world. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25:5–14. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Long TG. The funeral: changing patterns and teachable moments. J Preachers. 1996;19:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mitka M. `Teachable moments' provide a means for physicians to lower alcohol abuse. JAMA: J Am Med Assn. 1998;279:1767. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.22.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Welch FC, Tisdale PC. Between parent and teacher. Springfield: Charles C Thomas; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 82.McBride CM, Ostroff JS. Teachable moments for promoting smoking cessation: the context of cancer care and survivorship. Cancer Control : J of Moffitt Cancer Center. 2003;10:325–333. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 2003;18:156–170. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hochbaum GM. Public Participation in Medical Screening Programs: A Sociopsychological Study. Washington, DC: Government Printing office; 1958. PHS publication No. 572. [Google Scholar]

- 85.McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments for motivating smoking cessation. Health Educ Res Quart. 2003;18:156–170. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Boudreaux ED, Baumann BM, Camargo CA, O'Hea E, Ziedonis DM. Changes in smoking associated with an acute health event: theoretical and practical implications. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:189–199. doi: 10.1007/BF02879900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Street RL. Communication in medical encounters: an ecological perspective. In: Thompson TL, Dorsey AM, Miller KI, Parrott R, editors. Handbook of Health Communication. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Epstein RM, Street RL. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promotiong Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. Vol NIH Publication No. 07-6225. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Street RL. Information-giving in medical consultations: the influence of patients' communicative styles and personal characteristics. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:541–548. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90288-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Street RL. Analyzing communication in medical consultations: do behavioral measures correspond with patients' perceptions? Med Care. 1992;30:976–988. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199211000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]