Abstract

In the era of antiretroviral therapy, non-AIDS complications such as kidney disease are important contributors to morbidity and mortality.

Objective

To estimate the impact of hepatitis C co-infection on the risk of kidney disease in HIV patients.

Design/ Methods

Two investigators identified English-language citations in MEDLINE and Web of Science from 1989 through July 1, 2007. References of selected articles were reviewed. Observational studies and clinical trials of HIV-related kidney disease and antiretroviral nephrotoxicity were eligible if they included at least 50 participants and reported hepatitis C status. Data on study characteristics, population, and kidney disease outcomes were abstracted by two independent reviewers.

Results

After screening 2,516 articles, twenty-seven studies were eligible and 24 authors confirmed or provided data. Separate meta-analyses were performed for chronic kidney disease outcomes (n=10), proteinuria (n=4), acute renal failure (n=2), and indinavir toxicity (n=5). The pooled incidence of chronic kidney disease was higher in patients with hepatitis C co-infection (6.2% versus 4.0%; RR 1.49, 95% CI 1.08–2.06). In meta-regression, prevalence of black race and the proportion of patients with documented hepatitis C status were independently associated with the risk of chronic kidney disease. The relative risk associated with hepatitis C co-infection was significantly increased for proteinuria (1.15; 95% CI 1.02–1.30) and acute renal failure (1.64; 95% CI 1.21–2.23), with no significant statistical heterogeneity. The relative risk of indinavir toxicity was 1.59 (95% CI 0.99–2.54) with Hepatitis C co-infection.

Conclusions

Hepatitis C co-infection is associated with a significant increase in the risk of HIV-related kidney disease.

Introduction

Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) affects more than 30 million people worldwide 1. In the era of effective antiretroviral therapy, progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is less common, and non-AIDS complications such as kidney disease have become significant contributors to morbidity and mortality 2 3. From 1999–2003, there were more than 4,000 new cases of end-stage renal disease attributed to HIV in the United States 4, primarily in African-Americans 5,6. With improvements in the survival of HIV-infected dialysis patients 7 and increasing prevalence of HIV infection among African-Americans, the prevalence of HIV-related end-stage renal disease continues to rise 8. The increased recognition of kidney disease as an important non-AIDS complication is evident in the recent publication of consensus guidelines for the detection and management of chronic kidney disease in patients with HIV 9.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) co-infection is another increasingly important cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV 2 10, and affects approximately 30% of HIV-infected individuals. 11 Studies have demonstrated that co-infection with HIV and HCV translates into higher morbidity and mortality related to end-stage liver disease. 12 Definitive studies of the impact of HIV-HCV co-infection on kidney disease are lacking, although expert guidelines include HCV co-infection as a possible risk factor for kidney disease 9. In the general population, studies of the impact of HCV infection on the risk for kidney disease have produced inconsistent results. Data from the United States Veterans Affairs Medical System support an association between HCV infection and risk for end-stage renal disease.13 In contrast, nationally representative data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) suggest a negative association between HCV infection and early declines in kidney function, and only a weak association between HCV infection and increased risk for proteinuria. 14 While some smaller cohorts have demonstrated an increased risk of kidney disease outcomes associated with HIV-HCV co-infection, 15 16 others have failed to find a significant association, 17 18 or have even suggested a decreased risk in co-infected patients. 19 20

Both HIV and HCV have been implicated in the pathogenesis of specific glomerular diseases 21, and both viruses have been associated with immune dysregulation 22 and diabetes mellitus 23 24 25, which may contribute to the development of comorbid kidney disease. In addition, complex antiviral regimens for HIV and HCV often include medications with nephrotoxic potential. 9 26 27 With the disproportionate burden of HIV-HCV coinfection in minority populations at increased risk of kidney disease, 11 identification of HCV co-infection as a risk factor for kidney disease would have significant implications for public health and for clinical care. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify studies of kidney disease in HIV-infected patients with known HCV status, and performed a meta-analysis of available data to estimate the impact of HCV co-infection on the risk of kidney disease in patients with HIV.

Methods

This work was performed in accordance with published guidelines for systematic review, analysis, and reporting for meta-analyses of observational studies. 28

Literature Review and Study Selection

Two authors independently reviewed English-language citations from the MEDLINE database from 1989 through July 1, 2007, using the search terms “HIV” or “AIDS” and “renal” or “kidney” or “nephropathy.” Data on HCV status were not available prior to 1989, when the first assay for HCV antibodies was described. 29 An additional search was conducted to identify studies of renal adverse events associated with antiretroviral therapy, using the search terms “antiretroviral” or “indinavir” or “tenofovir” and “renal” or “kidney” or “toxicity.” MEDLINE searches were limited to human studies. A second database search was performed via the Science Citation Index Expanded on the Web of Science, and the references of all selected articles were reviewed to identify any additional studies.

Observational studies of kidney disease in HIV-infected patients were selected for further review if the study included at least 50 subjects and collected data on HCV status. Clinical trials and observational studies of the antiretroviral agents indinavir and tenofovir were included if data on renal adverse events and HCV status were reported. Nephrology referral cohorts and biopsy series were excluded unless they described kidney disease prevalence in the source population or included data on kidney disease progression. Because of the low prevalence of HCV infection in children, pediatric studies were not included. Unpublished studies and abstracts were not considered for inclusion in this meta-analysis. Data on study design, study period, patient characteristics, HCV prevalence, and kidney disease outcomes were abstracted by two independent reviewers. All authors of selected articles were contacted to obtain missing data and to confirm published results. Authors were asked to confirm or provide data on the age of the study population, the proportion with documented HCV status and the method used to determine HCV status (HCV antibody or RNA testing), the prevalence of black race, and the distribution of kidney disease endpoints among subjects with and without HCV co-infection, including only those subjects with documented HCV status.

Manuscript quality was assessed using criteria adapted from Hayden et al. 30 Eligible studies were included in the meta-analysis if adequate data on renal outcomes were available from published results or provided by the study author. Only data from subjects with known HCV status were included in the meta-analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We assessed several kidney disease outcomes in patients with HIV-HCV co-infection compared to outcomes in patients with HIV alone in stratified 2×2 contingency tables. We pooled outcomes based on clinical and biological grounds; for example, doubling of serum creatinine in a longitudinal study was considered a “chronic kidney disease” outcome. Overall results for each type of outcome were mathematically pooled using techniques that accounted for within and between study heterogeneity (random effects method of DerSimonian and Laird). 31 We formally assessed heterogeneity of treatment effects among studies with the Cochran Q and the I2 statistics. 32 To examine the association of study-level characteristics and treatment effect, we fitted random-effects meta-regression models to the natural logarithm of the relative risks by using the PROC GLM procedure in SAS statistical software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). We performed subgroup analyses of the factors that were significantly associated with the risk of renal outcomes in the meta-regression models. Publication bias was assessed by examination of funnel plots. All meta-analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta Analysis 1.0.25 (Englewood, NJ).

Results

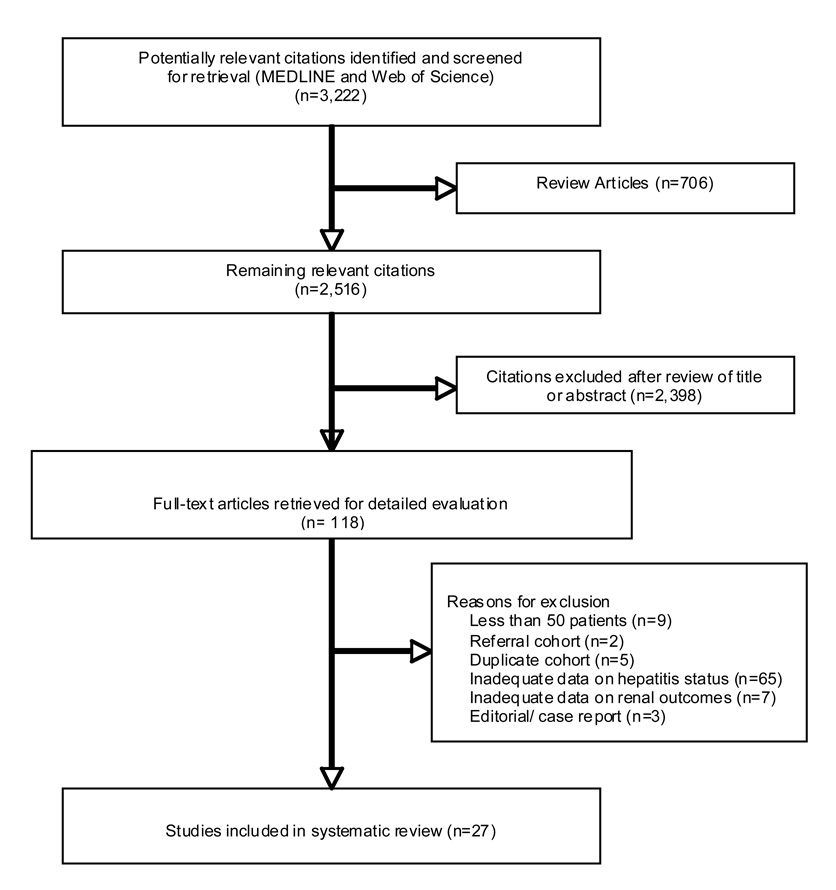

We identified 3,219 citations meeting our MEDLINE search criteria. After excluding review articles, 2,513 abstracts were evaluated, and 121 articles were selected for further review (Figure 1). Twenty-seven articles met our criteria for inclusion in the summary table, including 22 articles with adequate data for inclusion in our meta-analysis. 33 19 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 17 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 20 49 50 51 15 52 53 18 54 Two of the eligible papers reported outcomes from the same cohort 40 41; therefore, a total of 21 studies were included in the pooled analyses (Table 1–Table 2). Only 18 studies provided a clear definition of HCV co-infection, and only one study required HCV RNA testing for diagnosis. 53 Thirteen of 20 longitudinal studies did not include any information on patient attrition, and only one described the characteristics of patients lost to follow-up. Fifteen studies reported data on age, race, antiretroviral use, and CD4 cell count, although only five studies accounted for all four important potential confounders in their analyses.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of studies of HIV-related kidney disease considered for inclusion.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Studies of HIV-Related Kidney Disease Outcomes

| Source | Country | # of patients | Years of enrollment | Study type | Age, years | HCV % Known | HCV % Positive | Black race, % | Male, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahuja et al 1999 | United States | 557 | 1998 | CS | 37 | 100 | 23.3 | 50.0 | 79.7 |

| Bagnis et al, 2006 | France | 1219 | 2001 | CS | 42 | 78.8 | 14.2 | NA | 76.1 |

| Becker et al, 2004 | United States | 6022 | 1997–2003 | PC | 43 | NA | 11.4 | 14.9 | 90.9 |

| Brodie et al, 1998 | United States | 79 | 1995–1997 | RC | NA | 93.7 | 34.2 | NA | 60.8 |

| Dieleman et al, 2003 | Netherlands | 184 | 1998–2000 | PC | 41 | 41.8 | 6.0 | NA | 81.3 |

| Duval et al, 2004 | France | 1155 | 1997–1999 | PC | 36 | 90.4 | 23.7 | NA | 77 |

| Franceschini et al, 2006 | United States | 705 | 2000–2002 | PC | 40 | 100 | 22.7 | 61.0 | 68.7 |

| Gallant et al, 2005 | United States | 658 | 2001–2003 | RC | 38 | NA | 36.9 | 73.7 | 71.6 |

| Gardner et al, 2003a | United States | 885 | 1993–2000 | PC | NA | 98.8 | 56.3 | 60.8 | 0 |

| Gardner et al, 2003b | United States | 885 | 1993–2000 | PC | NA | 98.8 | 56.3 | 60.8 | 0 |

| Gupta et al, 2004 | United States | 487 | 1990–1998 | RC | 34 | 52.4 | 13.6 | 52.4 | 81.5 |

| Jung et al, 2004 | Germany | 214 | 2001–2002 | PC | 42 | 100 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 89.7 |

| Krawczyk et al, 2004 | United States | 394 | 1992–2002 | CC | 43 | 100 | 21.1 | 48.0 | 82.2 |

| Kulkarni et al, 2003 | United States | 828 | 1993–1998 | RC | 31 | 62 | 58.1 | 23.8 | 100 |

| Lopes et al, 2007 | Portugal | 97 | 2002–2006 | RC | 43 | 100 | 20.6 | 28.9 | 79.4 |

| Lucas et al, 2004 | United States | 3976 | 1989–2001 | PC | 37 | 74.5 | 52 | 77.0 | 70 |

| Malavaud et al, 2001 | France | 112 | 1998 | CC | 40 | 100 | 11.6 | NA | 73.2 |

| Meraviglia et al, 2002 | Italy | 555 | 1997 | PC | 38 | 100 | 46.1 | 1.4 | 77.1 |

| Mocroft et al, 2007 | Europe | 4474 | 2004–2005 | CS | 43 | 84.9 | 20.6 | 14.5* | 76.1 |

| Padilla et al, 2005 | Spain | 316 | 2001–2003 | CC | 40 | 54.7 | 32.0 | 1.3 | 76.0 |

| Reisler et al, 2003 | United States | 2947 | 1996–2001 | PC | 39 | 55.2 | 9.9 | 44.8 | 83.0 |

| Shahinian et al, 2000 | United States | 389 | 1992–1997 | CS | 40 | 47.8 | 20.6 | 54.0 | 93.1 |

| Szczech et al, 2002 | United States | 2057 | 1994–1999 | PC | 37 | 100 | 41.5 | 55.5 | 0 |

| Szczech et al, 2004 | United States | 89 | 1995–2001 | RC | 42¶ | 92.1 | 47.2 | 88.8 | 82.0 |

| Szczech et al, 2007 | United States | 760 | 1999 | CS | 44 | 100 | 23.2 | 44.0 | 73.7 |

| Tedaldi et al, 2003 | United States | 823 | 1996–2001 | PC | 37¶ | 100 | 32.4 | 64.3* | NA |

| Winston et al, 2006 | Australia | 948 | 2005 | PC | 45¶ | NA | 7.1 | NA | 95.8 |

Abbreviations CS, Cross-sectional, PC, Prospective cohort, RC, Retrospective cohort, CC, case control, HCV, Hepatits C virus status, NA, Not available

weighted average

Non-white race; all percentages represent the proportion of the total study population

Table 2.

Kidney Disease Outcomes in Patients with HIV and HIV-Hepatitis C Co-Infection.

| Outcomes, % | Reported Effect Size | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Outcome Definition | Length of f/u | HCV | No HCV | Univariate | Adjusted | Attrition |

| Ahuja et al | Proteinuria > 1.5g/day | … | 3.9 | 2.3 | 1.7 (0.4–5.5) | NA | … |

| Bagnis et al | ↑creatinine | … | 2.9 | 4.0 | ↓creatinine | NA | … |

| Becker et al | Hemolytic uremic syndrome | Median 4.1 yrs | 0.7 | 0.2 | NA | NA | 13% |

| Brodie et al | Nephrolithiasis (IDV) | 2 yrs | 37.0 | 12.8 | 4.0 (1.1–15.5) | 4.0 | NA |

| Dieleman et al | Pyuria (IDV) | Median 48 wks | 18.2 | 20.0 | NS | NA | NA |

| Duval et al | Renal SAE (PI) | Median 1.9 yrs | 4.0 | 2.2 | NA | NA | NA |

| Franceschini et al | Acute renal failure | 2 yrs | 15.0 | 8.3 | * | * | NA |

| Gallant et al | Δ creatinine clearance (TDF) | Median 1 yr | Δ −9% | Δ −8% | NS | NA | NA |

| Gardner et ala | ↑creatinine or proteinuria | 21 mos | 25.1 | 16.9 | NA | NA | NA |

| Gardner et alb | Renal hospitalization | 21 mos | 9.4 | 3.5 | NA | 1.7 (.05–5.5) | 13% |

| Gupta et al | Doubling of creatinine | 5 years | 7.6 | 2.1 | 3.8 (0.8–19.6) | NA | NA |

| Jung et al | Persistent proteinuria | 12–15 mos | 28.6 | 12.1 | NS | NA | 17% |

| Krawczyk et al | Confirmed diagnosis of CKD | 4–5.1 yrs | 21.7 | 20.0 | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | NS | … |

| Kulkarni et al | Documented renal diagnosis | 6 yrs | 4.8 | 3.1 | NA | NA | NA |

| Lopes et al | Acute renal failure in ICU | Admission | 65.0 | 42.9 | NA | 3.4 (1.1–10.9) | NA |

| Lucas et al | Clinical or histologic HIVAN | 11,732 pyrs | 3.6 | 1.8 | 2.0 (1.2–3.4) | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) | 10% |

| Malavaud et al | Nephrolithiasis (IDV) | … | 46.2 | 21.2 | NS | NA | … |

| Meraviglia et al | Renal colic (IDV) | 24 mos | 24.2 | 23.1 | NS | NA | … |

| Mocroft et al | Creatinine clearance < 60 | … | 3.5 | 4.7 | NA | NA | … |

| Padilla et al | Graded creatinine (TDF) | Median 48 wks | 2.0 | 2.8 | NS | NA | … |

| Reisler et al | Renal adverse event | Median 21 mos | 1.7 | 0.5 | NS | NA | NA |

| Shahinian et al | Biopsy diagnosis of HIVAN | … | NA | NA | NS | NA | … |

| Szczech et al | Proteinuria Doubling of creatinine |

5 yrs | 35.3 3.1 |

30.8 1.5 |

NA NA |

1.3 (1.2–1.4) * |

19% |

| Szczech et al | Time to ESRD | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2.6 (1.3–5.4) | NA |

| Szczech et al | Microalbuminuria | … | 11.4 | 10.8 | NA | NA | … |

| Tedaldi et al | Documented kidney disease | 2.7–3.1 yrs | 6.0 | 3.1 | 2.0 (1.0–3.8) | 1.8 (0.9–3.6) | 13% |

| Winston et al | Δ creatinine clearance (TDF) | NA | NA | NA | NS | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: IDV, indinavir, PI, protease inhibitor, TDF, tenofovir, ICU, intensive care unit, yrs, years, pyrs, patient years, …, not applicable, NA, not available, f/u, follow-up, CKD, chronic kidney disease, NS, no significant association

data available for subgroups

Study and patient characteristics from the selected articles are summarized in Table 1. The majority of studies were performed in the United States or Western Europe. Several different study designs are represented, most commonly prospective (n=14) and retrospective cohort studies (n=6). Sixteen studies were performed after the widespread introduction of effective combination antiretroviral therapy in 1996, and 11 studies spanned the years before and after 1996. Among the 19 studies that provided complete data on race, the prevalence of black race ranged from 1%–89%. The prevalence of documented HCV co-infection ranged from 3%–58.1% across studies.

The most frequently measured kidney disease outcomes (Table 2) included longitudinal measures of progression (time to end-stage renal disease, doubling of serum creatinine, decline in creatinine clearance) and cross-sectional measures of laboratory abnormalities (microalbuminuria, proteinuria, or elevated serum creatinine). Other studies analyzed the incidence of treatment-associated renal adverse events, the prevalence of documented acute or chronic kidney disease, and the incidence or prevalence of specific kidney diseases (HIV-associated nephropathy and hemolytic uremic syndrome). One study evaluated the frequency of hospitalization for kidney disease. Several studies contributed data on more than one kidney disease outcome, 15 40,41 48 but each cohort was only represented once in any meta-analysis. The authors of 24 studies provided additional information and/or confirmed abstracted data, including age of the study population, the proportion with documented HCV status, the method used to determine HCV status, the prevalence of black race, and the distribution of kidney disease endpoints among subjects with and without HCV co-infection.

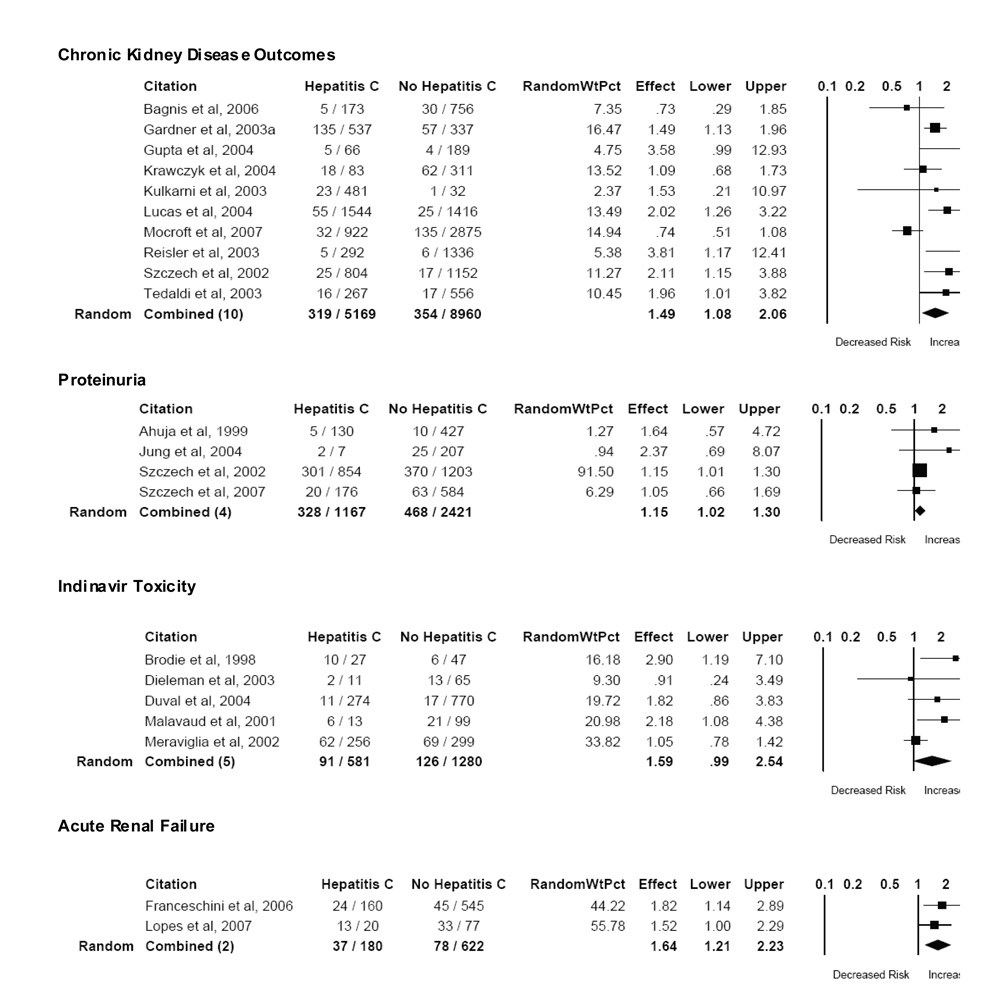

Chronic Kidney Disease

Twelve studies provided data on the prevalence, incidence, or progression of chronic kidney disease in patients with HCV co-infection, including HIV-associated nephropathy. 19 40 17 43 44 46 20 50 51 15 52 18 Ten studies with adequate data were included in the meta-analysis, representing more than 14,000 individuals with HIV infection (Figure 2). The definition of chronic kidney disease varied among studies, but was most commonly based on an elevation in serum creatinine or a decrease in creatinine clearance (n=4). One additional study described a combined endpoint of elevated serum creatinine or proteinuria, and 4 studies described the prevalence or incidence of a documented renal diagnosis. A single study of incident HIV-associated nephropathy was also included in this group. The absolute incidence of chronic kidney disease in patients without HCV co-infection ranged from < 1% to 16.9% (pooled incidence 4.0%) and in patients with HCV co-infection ranged from 1.7 to 25.1% (pooled incidence 6.2%). The pooled relative risk of chronic kidney disease in patients with HIV-HCV co-infection compared to those without HCV co-infection was 1.49 (95% CI 1.08–2.06), with some evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Q=24.0, P=0.004, I2 = 62.5%).

Figure 2.

Pooled Analysis of Kidney Disease Outcomes

Only three studies provided adjusted estimates of the chronic kidney disease outcomes in patients with HCV co-infection (Table 2). One study reported age-adjusted estimates, 18 while two studies adjusted for age, race, antiretroviral use, and severity of HIV disease. 46 52 The association between HCV co-infection and progression of chronic kidney disease remained highly significant in one study (adjusted HR 2.6; 95% CI 1.26–5.37), 52 which was not included in meta-analysis because of unavailable data. In the other two cohorts, there was a strong trend towards an association between HCV co-infection and chronic kidney disease in adjusted analyses.

Proteinuria

Four studies reported the prevalence of proteinuria in patients with HIV-HCV co-infection, totaling 3,588 individuals with HIV infection. Two studies defined proteinuria by standard dipstick urinalysis, one study described the prevalence of microalbuminuria, and one study defined significant proteinuria as a 24-hour urine protein excretion of at least 1.5 grams. The pooled prevalence of proteinuria in patients without HCV co-infection was 19.3%, compared to 28% in patients with HCV co-infection (Figure 2). The pooled relative risk of proteinuria in patients with HIV-HCV co-infection compared to those without HCV co-infection was 1.15 (95% CI 1.02–1.30). There was no evidence of substantial statistical heterogeneity (Q=1.9, P=0.59, I2 = 0%). Only one study reported an adjusted odds ratio for HCV co-infection. After adjusting for age, race, antiretroviral use, and CD4 cell count, HCV co-infection remained associated with a modest increase in the odds of proteinuria in that study (adjusted OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.16–1.35). 15

Antiretroviral nephrotoxicity

Eight studies addressed nephrotoxic or urologic complications of antiretroviral agents, primarily tenofovir (n=3) 39 49 54 and indinavir (n=4). 35 36 37 47 48 One study evaluated the incidence of adverse drug events in patients initiating therapy containing any protease inhibitor, and data on renal adverse events were provided by the authors 37. Additional data were provided for two studies of tenofovir toxicity; 39,49 however, adequate data for meta-analysis were only available for one study. 49 None of the three studies demonstrated an association between HCV co-infection and increased risk for tenofovir nephrotoxicity (Table 2), although pooled analysis was not possible.

Data were available for meta-analysis for all five studies involving indinavir or other protease inhibitors (Figure 2). 35,36,47,48 The absolute incidence of renal or urologic complications in patients without HCV co-infection ranged from 2 to 21% (pooled incidence 9.8%) and in patients with HCV co-infection ranged from 4 to 46% (pooled incidence 15.7%). The pooled relative risk of indinavir toxicity in patients with HIV-HCV co-infection compared to those without HCV co-infection was 1.59 (95% CI 0.99–2.54). There was some evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Q=8.2, P=0.08, I2 = 51.3%).

Acute Renal Failure

Two studies focused on the incidence of acute renal failure in patients with HIV (Figure 2). Both studies used criteria based on an acute rise in serum creatinine relative to baseline values. The absolute incidence of acute renal failure in patients without HCV co-infection was 8% in an ambulatory cohort 38 and 43% in critically ill patients 45 (pooled incidence 12.5%), and risk of acute renal failure in patients with HCV co-infection was 15% and 65%, respectively (pooled incidence 20.6%). The pooled relative risk of acute renal failure in patients with HIV-HCV co-infection compared to those without HCV co-infection was 1.64 (95% CI 1.21–2.23; Q=0.37, P=0.54, I2 = 0%). In both studies, the association between HCV co-infection and acute renal failure remained significant in multivariate analysis (Table 2).

Meta-regression and Subgroup Analyses

Meta-regression was used to identify study-level factors that may have contributed to the statistical heterogeneity observed in pooled analyses of chronic kidney disease and indinavir-related outcomes. For studies examining chronic kidney disease, two study-level factors were significantly associated with the relative risk of chronic kidney disease. These factors were the percentage of individuals with confirmed HCV status (p=0.01) and the percentage of black patients in the cohort (p=0.004). For studies examining indinavir-related toxicity, no study-level factor was associated with the demonstrated effect.

We performed two subgroup analyses based on the results of our meta-regression. Only three studies exploring chronic kidney disease outcomes documented HCV status in 100% of subjects. 43 15 18 The pooled relative risk in these 3 studies was 1.59 (95% CI 0.98–2.57), with less statistical heterogeneity compared to the pooled analysis of all 10 studies (Q=3.68, p=0.16, I2 =46%). Pooled analysis of the studies without universal documentation of HCV status yielded a similar point estimate (pooled RR 1.37, 95% CI 0.8–2.37; Q=16.32, p=0.006). For the second study-level factor, the regression line demonstrated that there was an increased relative risk of chronic kidney disease in studies with more than 25% black subjects. A separate meta-analysis including the 7 studies with a higher prevalence of black race (>25%) demonstrated a pooled relative risk of 1.72 for chronic kidney disease in patients with HCV co-infection (95% CI 1.33–2.23; Q=8.6, p=0.2, I2 = 30%). In contrast, HCV co-infection was not associated with increased risk of chronic kidney disease in pooled analysis of the three studies with a lower prevalence of black race (pooled RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.53–1.07; Q=0.51, p=0.77).

Discussion

The results of the current meta-analysis suggest that HIV-HCV co-infection is associated with an increased risk of kidney disease compared to HIV infection alone. In pooled analyses of data from more than 18,000 HIV infected patients, HCV co-infection was associated with an increased risk of chronic kidney disease by nearly 50%, proteinuria by 15%, and acute renal failure by 64%, and with an increased risk for urologic and nephrotoxic complications of the antiretroviral agent indinavir. These findings have important implications for clinical care and for global public health, and they may provide a new impetus for pathogenic studies of kidney disease in patients with HIV and HCV.

The demonstrated association between HCV co-infection and risk for acute and chronic kidney disease supports existing guidelines for the diagnosis and management of kidney disease in patients with HIV. 9 These consensus guidelines consider HCV co-infection a risk factor for kidney disease, and recommend increased frequency of screening for proteinuria and decline in glomerular filtration rate. Timely recognition of kidney disease may allow targeted therapy to delay progression, and is essential to guide selection and dosing of antiretroviral medications. The impact of HCV co-infection on the risk for antiretroviral nephrotoxicity has not been well described, in part because data on HCV status have not been routinely reported in clinical trials of the relevant agents. Available data do not suggest an increased risk for tenofovir nephrotoxicity in patients with HCV co-infection, although future studies should be encouraged to collect and report data on HCV status. 39,49,54 The results of the current meta-analysis demonstrate a trend towards increased risk of nephrotoxic/urologic complications of indinavir in patients with HIV-HCV co-infection. Although indinavir has been largely replaced by newer protease inhibitors in the United States and Western Europe, it is still commonly used in Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe, regions with increased HCV seroprevalence. 55 Since the prevalence of HIV-HCV co-infection varies widely based on the primary mode of HIV transmission,11 the local prevalence of HCV co-infection may be an important consideration in the choice of appropriate antiretroviral regimens for use in resource-limited settings.

While this is the first quantitative review to address this important clinical question, systematic reviews have a number of inherent limitations. Most importantly, this review is limited by heterogeneity in the design and quality of the available studies. The majority of longitudinal studies did not adequately describe study attrition, and the inclusion of cross-sectional studies limits the ability to establish temporal relationships. The prevalence and impact of important potential confounders were not reported in all studies; in particular, data on race were missing from six studies, primarily from studies conducted in Europe and Australia. The prevalence of black race is likely to be lower in these study populations, which may significantly decrease the background risk of kidney disease 20 5,6,56. A sensitivity analysis excluding studies with a prevalence of black race below 25% yielded qualitatively similar results, with noticeably less statistical heterogeneity. In addition to the variability in race, there was also significant variability in the kidney disease outcomes measured in the individual studies, and it is possible that HCV co-infection has heterogeneous effects. For example, black race is strongly associated with HIV-related chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease 6 4 5, but does not appear to be a risk factor for acute renal failure in patients with HIV 16,57. HCV co-infection may also have heterogeneous effects on different renal outcomes, including the diverse endpoints considered together as chronic kidney disease in the current analysis. Of interest, the effect size was similar for studies of chronic kidney disease and acute renal failure, although this conclusion is limited by the inclusion of only 2 studies of acute renal failure. Another important limitation of the current study involves the assessment of HCV status. The proportion of study subjects with documented HCV status ranged from 42%–100% across studies, with universal documentation of HCV status in fewer than half of the studies. Although only data from subjects with known HCV status were included in the current meta-analysis, the lack of universal HCV screening may have biased our study population. Comparisons between subjects with and without documented HCV status were not possible based on study-level data.

Few of the studies included in the current meta-analysis provided adjusted estimates of the risk for kidney disease associated with HCV co-infection. The observed association between HCV co-infection and increased risk for kidney disease could reflect confounding by other factors, such as older age, black race, history of injection drug use, or exposure to nephrotoxic medications. Data on potential mediators such as diabetes, cryoglobulinemia, and end-stage liver disease were also not reported in most studies. In conclusion, HCV coinfection in HIV-positive patients is associated with an increased risk of kidney disease. Health care providers should be aware of this risk, and future studies should investigate the mechanism of the observed association to allow for targeted interventions in susceptible patients. In the interim, patients with HIV-HCV co-infection should be regarded as being at increased risk for acute and chronic kidney disease, regardless of the presence of traditional kidney disease risk factors.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of the investigators who have generously provided or confirmed data from the included studies. Systematic review and data abstraction were performed by CW and CM. All authors participated in the analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript.

Sponsorship: This work was supported in part by NIH grants K23 DK077568 (CW), F32 DK076318 (SC), K23 DK64689 (CP), and P01DK56492-05 (CW, PK).

Footnotes

Disclosures: CMW has received honoraria from Gilead Sciences and research support from the Gilead Foundation. PEK is on the scientific advisory board of Gilead Sciences.

Contributor Information

Christina M. Wyatt, Department of Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY Email: Christina.wyatt@mssm.edu.

Carlos Malvestutto, Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY Email: carlos.malvestutto@mssm.edu.

Steven G. Coca, Department of Medicine, Section of Nephrology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT Email: steven.coca@yale.edu.

Paul E. Klotman, Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY Email: paul.klotman@mssm.edu.

Chirag R. Parikh, Department of Medicine, Section of Nephrology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT Email: chirag.parikh@yale.edu.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. UNAIDS/WHO AIDS Epidemic Update. 2006 December; 2006.

- 2.Selik RM, Byers RH, Jr, Dworkin MS. Trends in diseases reported on U.S. death certificates that mentioned HIV infection, 1987–1999. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:378–387. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200204010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, Gordin F, Abrams D, Arduino RC, Babiker A, Burman W, Clumeck N, Cohen CJ, Cohn D, Cooper D, Darbyshire J, Emery S, Fatkenheuer G, Gazzard B, Grund B, Hoy J, Klingman K, Losso M, Markowitz N, Neuhaus J, Phillips A, Rappoport C. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2283–2296. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2007 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End- Stage Renal Disease in the United States. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucas GM, Mehta SH, Atta MG, Kirk GD, Galai N, Vlahov D, Moore RD. End-stage renal disease and chronic kidney disease in a cohort of African-American HIV-infected and at-risk HIV-seronegative participants followed between 1988 and 2004. AIDS. 2007;21:2435–2443. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32827038ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi AI, Rodriguez RA, Bacchetti P, Bertenthal D, Volberding PA, O' hare AM. Racial Differences in End-Stage Renal Disease Rates in HIV Infection versus Diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbott KC, Hypolite I, Welch PG, Agodoa LY. Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome- associated nephropathy at end-stage renal disease in the United States: patient characteristics and survival in the pre highly active antiretroviral therapy era. J Nephrol. 2001;14:377–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz EJ, Szczech LA, Ross MJ, Klotman ME, Winston JA, Klotman PE. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and the epidemic of HIV+ end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2412–2420. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005040340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta SK, Eustace JA, Winston JA, Boydstun II, Ahuja TS, Rodriguez RA, Tashima KT, Roland M, Franceschini N, Palella FJ, Lennox JL, Klotman PE, Nachman SA, Hall SD, Szczech LA. Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected patients: recommendations of the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1559–1585. doi: 10.1086/430257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greub G, Ledergerber B, Battegay M, Grob P, Perrin L, Furrer H, Burgisser P, Erb P, Boggian K, Piffaretti JC, Hirschel B, Janin P, Francioli P, Flepp M, Telenti A. Clinical progression, survival, and immune recovery during antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus coinfection: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Lancet. 2000;356:1800–1805. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol. 2006;44:S6–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham CS, Baden LR, Yu E, Mrus JM, Carnie J, Heeren T, Koziel MJ. Influence of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the course of hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:562–569. doi: 10.1086/321909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsui JI, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG, Bertenthal D, Inadomi J, Rodriguez RA, O'Hare AM. Association of hepatitis C seropositivity with increased risk for developing end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1271–1276. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsui JI, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG, O'Hare AM. Relationship between hepatitis C and chronic kidney disease: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1168–1174. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005091006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szczech LA, Gange SJ, van der Horst C, Bartlett JA, Young M, Cohen MH, Anastos K, Klassen PS, Svetkey LP. Predictors of proteinuria and renal failure among women with HIV infection. Kidney Int. 2002;61:195–202. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franceschini N, Napravnik S, Eron JJJ, Szczech LA, Finn WF. Incidence and etiology of acute renal failure among ambulatory HIV-infected patients. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1526–1531. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta SK, Mamlin BW, Johnson CS, Dollins MD, Topf JM, Dube MP. Prevalence of proteinuria and the development of chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected patients. Clin Nephrol. 2004;61:1–6. doi: 10.5414/cnp61001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tedaldi EM, Baker RK, Moorman AC, Alzola CF, Furhrer J, McCabe RE, Wood KC, Holmberg SD. Influence of coinfection with hepatitis C virus on morbidity and mortality due to human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:363–367. doi: 10.1086/345953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isnard Bagnis C, Tezenas Du Montcel S, Fonfrede M, Jaudon MC, Thibault V, Carcelain G, Valantin MA, Izzedine H, Servais A, Katlama C, Deray G. Changing Electrolyte and Acido-Basic Profile in HIV-Infected Patients in the HAART Era. Nephron Physiol. 2006;(103):131–138. doi: 10.1159/000092247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mocroft A, Kirk O, Gatell J, Reiss P, Gargalianos P, Zilmer K, Beniowski M, Viard JP, Staszewski S, Lundgren JD. Chronic renal failure among HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS. 2007;21:1119–1127. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280f774ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson RJ, Gretch DR, Yamabe H, Hart J, Bacchi CE, Hartwell P, Couser WG, Corey L, Wener MH, Alpers CE, et al. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:465–470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302183280703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pawlotsky JM, Roudot-Thoraval F, Simmonds P, Mellor J, Ben Yahia MB, Andre C, Voisin MC, Intrator L, Zafrani ES, Duval J, Dhumeaux D. Extrahepatic immunologic manifestations in chronic hepatitis C and hepatitis C virus serotypes. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:169–173. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-3-199502010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown TT, Cole SR, Li X, Kingsley LA, Palella FJ, Riddler SA, Visscher BR, Margolick JB, Dobs AS. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence and incidence of diabetes mellitus in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1179–1184. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta SH, Brancati FL, Sulkowski MS, Strathdee SA, Szklo M, Thomas DL. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus among persons with hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:592–599. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shintani Y, Fujie H, Miyoshi H, Tsutsumi T, Tsukamoto K, Kimura S, Moriya K, Koike K. Hepatitis C virus infection and diabetes: direct involvement of the virus in the development of insulin resistance. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:840–848. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coca S, Perazella MA. Rapid communication: acute renal failure associated with tenofovir: evidence of drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Am J Med Sci. 2002;324:342–344. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200212000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willson RA. Nephrotoxicity of interferon alfa-ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:89–92. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200207000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuo G, Choo QL, Alter HJ, Gitnick GL, Redeker AG, Purcell RH, Miyamura T, Dienstag JL, Alter MJ, Stevens CE, et al. An assay for circulating antibodies to a major etiologic virus of human non-A, non-B hepatitis. Science. 1989;244:362–364. doi: 10.1126/science.2496467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayden JA, Cote P, Bombardier C. Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:427–437. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-6-200603210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahuja TS, Borucki M, Funtanilla M, Shahinian V, Hollander M, Rajaraman S. Is the prevalence of HIV-associated nephropathy decreasing? Am J Nephrol. 1999;19:655–659. doi: 10.1159/000013537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker S, Fusco G, Fusco J, Balu R, Gangjee S, Brennan C, Feinberg J. HIV-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: an observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39 Suppl 5:S267–S275. doi: 10.1086/422363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brodie SB, Keller MJ, Ewenstein BM, Sax PE. Variation in incidence of indinavir-associated nephrolithiasis among HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 1998;12:2433–2437. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199818000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dieleman JP, van Rossum AM, Stricker BC, Sturkenboom MC, de Groot R, Telgt D, Blok WL, Burger DM, Blijenberg BG, Zietse R, Gyssens IC. Persistent leukocyturia and loss of renal function in a prospectively monitored cohort of HIV-infected patients treated with indinavir. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:135–142. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200302010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duval X, Journot V, Leport C, Chene G, Dupon M, Cuzin L, May T, Morlat P, Waldner A, Salamon R, Raffi F. Incidence of and risk factors for adverse drug reactions in a prospective cohort of HIV-infected adults initiating protease inhibitor-containing therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:248–255. doi: 10.1086/422141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franceschini N, Napravnik S, Finn WF, Szczech LA, Eron JJJ. Immunosuppression, hepatitis C infection, and acute renal failure in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:368–372. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000220165.79736.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gallant JE, Parish MA, Keruly JC, Moore RD. Changes in renal function associated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment, compared with nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1194–1198. doi: 10.1086/428840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gardner LI, Holmberg SD, Williamson JM, Szczech LA, Carpenter CC, Rompalo AM, Schuman P, Klein RS. Development of proteinuria or elevated serum creatinine and mortality in HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:203–209. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200302010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardner LI, Klein RS, Szczech LA, Phelps RM, Tashima K, Rompalo AM, Schuman P, Sadek RF, Tong TC, Greenberg A, Holmberg SD. Rates and risk factors for condition-specific hospitalizations in HIV-infected and uninfected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34:320–330. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200311010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jung O, Bickel M, Ditting T, Rickerts V, Welk T, Helm EB, Staszewski S, Geiger H. Hypertension in HIV-1-infected patients and its impact on renal and cardiovascular integrity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2250–2258. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krawczyk CS, Holmberg SD, Moorman AC, Gardner LI, McGwin GJ. Factors associated with chronic renal failure in HIV-infected ambulatory patients. AIDS. 2004;18:2171–2178. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kulkarni R, Soucie JM, Evatt B. Renal disease among males with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2003;9:703–710. doi: 10.1046/j.1351-8216.2003.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lopes JA, Fernandes J, Jorge S, Neves J, Antunes F, Prata MM. Acute renal failure in critically ill HIV-infected patients. Crit Care. 2007;11(1):404. doi: 10.1186/cc5141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lucas GM, Eustace JA, Sozio S, Mentari EK, Appiah KA, Moore RD. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and the incidence of HIV-1-associated nephropathy: a 12-year cohort study. Aids. 2004;18:541–546. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200402200-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malavaud B, Dinh B, Bonnet E, Izopet J, Payen JL, Marchou B. Increased incidence of indinavir nephrolithiasis in patients with hepatitis B or C virus infection. Antivir Ther. 2000;5:3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meraviglia P, Angeli E, Del Sorbo F, Rombola G, Vigano P, Orlando G, Cordier L, Faggion I, Cargnel A. Risk factors for indinavir-related renal colic in HIV patients: predictive value of indinavir dose/body mass index. AIDS. 2002;16:2089–2093. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200210180-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Padilla S, Gutierrez F, Masia M, Canovas V, Orozco C. Low frequency of renal function impairment during one-year of therapy with tenofovir-containing regimens in the real-world: a case-control study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19:421–424. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reisler RB, Han C, Burman WJ, Tedaldi EM, Neaton JD. Grade 4 events are as important as AIDS events in the era of HAART. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34:379–386. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200312010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shahinian V, Rajaraman S, Borucki M, Grady J, Hollander WM, Ahuja TS. Prevalence of HIV-associated nephropathy in autopsies of HIV-infected patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:884–888. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szczech LA, Gupta SK, Habash R, Guasch A, Kalayjian R, Appel R, Fields TA, Svetkey LP, Flanagan KH, Klotman PE, Winston JA. The clinical epidemiology and course of the spectrum of renal diseases associated with HIV infection. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1145–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szczech LA, Grunfeld C, Scherzer R, Canchola JA, van der Horst C, Sidney S, Wohl D, Shlipak MG. Microalbuminuria in HIV infection. AIDS. 2007;21:1003–1009. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280d3587f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winston A, Amin J, Mallon P, Marriott D, Carr A, Cooper DA, Emery S. Minor changes in calculated creatinine clearance and anion-gap are associated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-containing highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2006;7:105–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.WHO. World Health Organization Media Centre: Hepatitis C

- 56.Wyatt CM, Winston JA, Malvestutto CD, Fishbein DA, Barash I, Cohen AJ, Klotman ME, Klotman PE. Chronic kidney disease in HIV infection: an urban epidemic. AIDS. 2007;21:2101–2103. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ef1bb4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wyatt CM, Arons RR, Klotman PE, Klotman ME. Acute renal failure in hospitalized patients with HIV: risk factors and impact on in-hospital mortality. Aids. 2006;20:561–565. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000210610.52836.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]