Abstract

Problem

Quick detection and response were essential for preventing outbreaks of infectious diseases after the Sichuan earthquake. However, the existing public health communication system in Sichuan province, China, was severely damaged by the earthquake.

Approach

The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention set up a mobile phone emergency reporting system. In total, 495 light-powered mobile phones were delivered to local health-care agencies in earthquake affected areas. All phones were loaded with software designed for inputting and transmitting cases of infectious disease directly to a national database for further analysis.

Local setting

The emergency reporting system was set up in 14 counties hit hardest by the earthquake in Sichuan province, China.

Relevant changes

One week after delivering mobile phones to earthquake-affected areas, the number of health-care agencies at the township level that had filed reports returned to the normal level. The number of cases reported by using mobile phones accounted for as much as 52.9% of the total cases reported weekly from 19 May to 13 July in those areas

Lessons learned

The mobile phone is a useful communication tool for infectious disease surveillance in areas hit by natural disasters. Nevertheless, plans must be made ahead of time and be included in emergency preparedness programmes.

Résumé

Problématique

Une détection et une riposte rapides sont essentielles pour prévenir les flambées épidémiques de maladies infectieuses après le tremblement de terre du Sichuan. Cependant, le système de communication en santé publique dont disposait la province du Sichuan a été gravement endommagé par le séisme.

Démarche

Le Centre chinois pour la lutte contre les maladies et leur prévention a mis en place un système de notification d’urgence par téléphone portable. Au total, 495 téléphones portables à batterie solaire ont été livrés aux agences sanitaires locales de la zone touchée par le séisme. Un logiciel conçu pour la saisie et la transmission directe à une base de données des cas de maladie infectieuse pour analyse plus poussée a été chargé sur chaque téléphone.

Contexte local

Le système de notification d’urgence a été mis en place dans les 14 comtés de la province du Sichuan les plus durement touchés par le séisme.

Modifications pertinentes

Une semaine après la livraison des téléphones portables dans les zones affectées, le nombre d’agences sanitaires au niveau des cantons envoyant des rapports était revenu à la normale. Le nombre de cas notifiés à l’aide des téléphones portables représentait près de 52,9 % du nombre total de cas notifiés par semaine entre le 19 mai et le 13 juillet dans ces zones.

Enseignements tirés

Le téléphone portable est un outil de communication utile pour la surveillance des maladies infectieuses dans les zones frappées par des catastrophes naturelles. Néanmoins, des plans doivent être établis à l’avance et intégrés aux programmes de préparation aux situations d’urgence.

Resumen

Problema

La detección y respuesta rápidas fueron esenciales para prevenir los brotes de enfermedades infecciosas después del terremoto de Sichuan. Sin embargo, el sistema de comunicación de salud pública empleado en esa provincia china se vio gravemente afectado por el terremoto.

Enfoque

El Centro para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades de China estableció un sistema de notificación de emergencia a base de teléfonos móviles. Se suministraron en total 495 teléfonos móviles alimentados por energía solar a organismos locales de atención sanitaria de las zonas afectadas por el terremoto. Todos los teléfonos disponían de software diseñado para registrar y notificar los casos de enfermedades infecciosas directamente a una base de datos nacional para su posterior análisis.

Contexto local

El sistema de notificación de emergencia se puso en marcha en las 14 circunscripciones de la provincia de Sichuan más castigadas por el terremoto.

Cambios destacables

Una semana después de suministrar los teléfonos móviles a las zonas afectadas por el seísmo, el número de organismos de atención sanitaria operativos a nivel municipal que registraban y notificaban los casos había aumentado hasta alcanzar los niveles habituales. El número de casos notificados usando los teléfonos móviles representó hasta el 52,9% del total de casos notificados semanalmente entre el 19 de mayo y el 13 de julio en esas zonas.

Enseñanzas extraídas

El teléfono móvil es un valioso instrumento de comunicación para la vigilancia de las enfermedades infecciosas en las zonas afectadas por desastres naturales. Sin embargo, es preciso planificar su uso con antelación e incluir esos planes en los programas de preparación para emergencias.

ملخص

المشكلة

كان الكشف والاستجابة المبكرة من الأمور الأساسية من أجل الوقاية من فاشيات الأمراض المعدية بعد زلزال سيشوان. إلا أن نظام الاتصالات الخاص بالصحة العمومية الذي كان موجوداً في ولاية سيشوان في الصين قد أصيب بضرر جسيم بسبب الزلزال.

الأسلوب

أنشأ المركز الصيني لمكافحة الأمراض والوقاية منها نظاماً للتبليغ الطارئ باستخدام الهواتف الجوالة. وقد زودت الوكالات المحلية المعنية بالرعاية الصحية بـ 495 هاتفاً جوَّالاً يعمل بالطاقة الضوئية. وكانت جميع هذه الهواتف قد حُمِّلت ببرمجيات مصممة لإدخال وبث حالات الأمراض المعدية إلى قاعدة معطيات وطنية بغرض إجراء المزيد من التحليل.

المرفق المحلي

تمت إقامة نظام التبليغ الطارئ في 14 مقاطعة تأثرت تأثراً شديداً بالزلزال في ولاية سيشوان في الصين.

التغيرات ذات الصلة

بعد أسبوع واحد من تزويد المناطق المتضررة من الزلزال بالهواتف الجوَّالة عاد عدد وكالات الرعاية الصحية على مستوى المدن والتي أرسلت تقارير للتبليغ عن الحالات، إلى المستوى الطبيعي. وقد شكّل عدد الحالات التي تم الإبلاغ عنها باستخدام الهواتف الجوَّالة 52.9% من العدد الكلي للحالات التي المبلغ عنها أسبوعياً، في المدة من 19 أيار/مايو إلى 13 تموز/يوليو، في تلك المناطق.

الدروس المستفادة

تُعَد الهواتف الجوَّالة من أدوات التواصل المفيدة في ترصُّد الأمراض الـمُعدية في المناطق التي تضربها الكوارث الطبيعية. ومع ذلك، ينبغي إعداد الخطط المسبقة وإدراجها في برامج التأهُّب للطوارئ.

Introduction

Infectious diseases in developing countries are common in populations displaced by natural disasters.1 Outbreaks of diarrhoeal disease after the flooding in Bangladesh in 2004 and in Pakistan after the 2005 earthquake attest to this.2,3 A functional infectious disease surveillance system in the disaster-hit area is crucial for reducing the risk of epidemics.1 Such a system, however, is often either nonexistent or damaged by the disaster itself.

On 12 May 2008, an earthquake with a magnitude of 8.0 struck the north-western part of Sichuan province, China. More than 80 000 people were killed and 5 million more became homeless. One urgent issue after the earthquake was the detection of occurrences of epidemic-prone diseases so that quick action could be taken to prevent outbreaks. Before the earthquake, the local health-care agencies were required to report 38 types of infectious diseases, as mandated by the law on prevention and treatment of infectious diseases, through the Chinese information system for disease control and prevention (CISDCP) to a national database.4 In Sichuan, this electronic disease surveillance system has been set up in all townships since 2004 using dial-up or broadband internet connections. The earthquake paralysed the system in those areas. While working to repair the landline-based reporting system, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) developed an emergency reporting system based on mobile phones. This paper describes that system and the lessons learned from the utilization of mobile phones for infectious disease surveillance after the catastrophic earthquake.

Methods

The mobile phone emergency reporting system was set up by China CDC and the local CDC offices in five steps: (i) selecting mobile phones and the network supplier; (ii) developing a reporting system to run on mobile phones; (iii) identifying places where the mobile phones would be needed; (iv) distributing the mobile phones and providing onsite training; and (v) applying quality control measures.

China CDC immediately secured a donation of light-powered mobile phones (A6000 model; GSM/GPRS duel bands) from Hi-Tech Wealth, a domestic mobile phone manufacturer. This model is recharged through a crystalline silicon solar panel embedded into the shell of the phone. China Mobile was selected as the network supplier because of its extensive coverage in the disaster zones.

China CDC developed a reporting system based on the short messaging system (known as SMS or text messaging) and covering the same 38 infectious diseases reported in CISDCP. An epidemiologist in the field can input 16 categories of information about a case, including the name of patient, age, diagnosis, time and location, into a form. Except for names of patients, all data are input as numerical codes, using the same codes for CISDCP. Information on each case is then sent as an encrypted text message to the national database. It takes approximately 2–3 minutes for a trained person to report a case. The reported data are analysed by China CDC and displayed on digital maps in real time.

The local CDC offices singled out health agencies in regions where the intensity of the earthquake was more than seven and the reports could not be transmitted via the normal route. The mobile phones were delivered to those agencies by staff from the local CDC offices and epidemiologists in those agencies were trained to use the reporting system.

A quality control system was in place to ensure the quality of data. When a doctor encountered a patient with an infectious disease in the field, he/she would fill out a paper form. The paper records in the township or relocation camp were collected and verified by an epidemiologist. The epidemiologist then sent the information through the mobile phone reporting system to the national database. The CDC offices at the county level would check the data received and ask for changes if the data were incomplete or errors were found. The CDC offices at the city and province level took regular random samples from the reported cases and verified the doctors’ records.

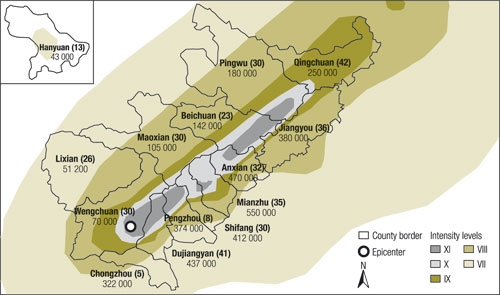

The SMS programme was developed, tested and loaded into all phones in 3 days. By 18 May, 6 days after the earthquake, the first batch of mobile phones was distributed to the health-care agencies in the hardest-hit areas. A total of 560 mobile phones were sent to Sichuan by China CDC; 495 phones were handed out to local health-care agencies; the remaining phones were reserved for replacing any lost or malfunctioning units. Health-care agencies in townships and temporary clinics set up in relocation camps received 423 phones. They were primary targets because they could not restore the regular reporting system as quickly as their counterparts at the county level. The distribution of those phones is shown in Fig. 1. On 22 May, the first case of infectious disease reported through the mobile phone system was received by China CDC in Beijing.

Fig. 1.

Map showing the intensity levels of the earthquake and the distribution of mobile phones in 14 selected counties, Sichuan, China, May 2008

Estimated number of people impacted by the earthquake, number of mobile phones distributed in parentheses.

Results

Health-care agencies that received mobile phones regained the ability to report cases of infectious diseases to the national database in a short time (Table 1). Immediately after the earthquake, a sharp decline can be seen both in the number of cases reported and the number of reporting agencies that filed reports. Those numbers quickly rebounded to the previously recorded levels after the delivery of mobile phones. The mobile phone reporting system was used most intensively in the first 2 months after the earthquake. Compared to the average number of cases reported in the same period in 2005–2007, the cases reported after the earthquake decreased by 17.8%. However, the number of health-care agencies that filed reports remained the same.

Table 1. Weekly reports of infectious diseases filed by health-care agencies at the township level in earthquake-affected areas between 5 May and 13 July 2008.

| Weeks | Number of cases reported |

Number of agencies that field reports |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Averagea | Totalb | Cases reported using mobile phones | % of cases reported using mobile phones | Averagea | Totalc | Agencies using mobile phones | % of agencies using mobile phones | ||

| 5–11 May | 164 | 197 | 0 | 0 | 103 | 136 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12–18 May | 174 | 97 | 0 | 0 | 113 | 65 | 0 | 0 | |

| 19–25 May | 169 | 192 | 55 | 28.6 | 115 | 116 | 25 | 21.6 | |

| 26 May–1 June | 253 | 319 | 172 | 53.9 | 136 | 206 | 107 | 51.9 | |

| 2–8 June | 219 | 182 | 88 | 48.4 | 134 | 128 | 63 | 49.2 | |

| 9–15 June | 282 | 172 | 68 | 39.5 | 151 | 134 | 50 | 37.3 | |

| 16–22 June | 253 | 179 | 49 | 27.4 | 147 | 147 | 42 | 28.6 | |

| 23–29 June | 257 | 144 | 36 | 25.0 | 141 | 118 | 27 | 22.9 | |

| 30 June–6 July | 180 | 149 | 22 | 14.8 | 115 | 121 | 18 | 14.9 | |

| 7–13 July | 199 | 138 | 6 | 4.3 | 129 | 112 | 5 | 4.5 | |

a Three-year averages (2005–2007) are listed for comparison. b The total number of reported cases includes cases filed from both the Chinese information system for disease control and prevention (CISDCP) and the mobile phone reporting system. c The total number of agencies that filed reports includes agencies where only CISDCP was used and those where only the mobile phone reporting system was used. No agencies run both systems simultaneously.

Before the earthquake, the average reporting delay was 0.72 hours for infectious diseases classified as Class A and 11.5 hours for Class B and Class C infectious diseases. After the earthquake, no Class A infectious diseases were reported; the average reporting delays for Class B and Class C infectious diseases was between 12 and 24 hours, less than the 24 hours that is required by the law. There was a significant increase in the occurrence of diarrhoeal diseases when compared to reports filed before the earthquake. No significant differences were identified for other diseases.

Discussion

The result indicates that the mobile phone reporting system helped restore the reporting capacity of health-care agencies in earthquake-affected areas. The drop in the number of cases reported might have been caused by two factors: (i) the rate of unreported cases increased because doctors were flooded with patients after the earthquake. A quality check applied in four counties found out that the average rate of unreported cases after the earthquake was 6.7% higher than the rate before the earthquake; (ii) the occurrence of infectious disease in some areas was possibly lower than in past years due to the stringent disease prevention and control measures adopted by Chinese authorities after the earthquake.

The system met the designer’s goals in several ways. First, the system is easy to navigate; the average time needed for training a health worker to run the system on a mobile phone was less than half an hour. Second, the network coverage for mobile phones in China is extensive; China mobile, the largest network supplier in China, can reach 97% of the Chinese population. The mobile phone service in earthquake-affected areas was restored within 2 days after the earthquake. Finally, the mobility of this system allows health workers to move with relocated people and continue to report cases of diseases.

The mobile phone, with its low cost and universal availability, has been recognized as an important piece of communication technology in health care, especially in telemedicine.5 However, published studies on using mobile phones in disease surveillance are still limited. In Uganda, an international, non-profit organization, AED-SATELLIFE, is testing a disease surveillance reporting system based on mobile phones.6 In Peru, the Naval Medical Research Center Detachment of the United States of America has included mobile phones as part of its electronic disease surveillance system (Alerta) since 2002.7 In the Islamic Republic of Iran, mobile phones are used in a communicable disease surveillance system for 27 medical universities.8 Voxiva, an American company, is helping Indonesia to use mobile phones to report avian influenza.9 Unlike those countries where limited resources and remote locations are the main reasons for using mobile phones, China is able to cover the entire country with an electronic disease surveillance system based on landlines. However, landline-based systems are vulnerable in catastrophic events, as seen in this case and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in the United States of America.10 Therefore, a disease surveillance system based on mobile phones is not only a good choice for countries with poor infrastructure but could also be used as a viable backup method for countries with internet-based electronic surveillance systems. As far as we know, the reporting system described in this paper is the only case in which mobile phones have been systematically used in disease surveillance after a major natural disaster.

Conclusion

Some lessons that we have learned from developing and running this system may be useful for other countries that want to consider using mobile phones in similar situations (Box 1). First of all, it will be more effective to incorporate this system as part of a regular emergency preparation programme. In this case, there was a rush to act after the normal disease surveillance system was paralysed by the earthquake. Thus, a delay was unavoidable due to the time needed to design the system and deliver the mobile phones. A possible alternative is to ask health workers to download the reporting programme to their own mobile phones and use it when needed. We also learned that some restrictions have to be applied to the use of phones. We had to shut off the calling function of mobile phones after one month because some agencies were using the phones for other activities. Those agencies ran out of prepaid minutes, as we had planned this amount for each phone based on the estimated upper limit of the number of cases that would be reported. Last, whenever possible, mobile phones with global positioning system (GPS) capacity should be used. The reporting system can be programmed to attach coordinate data to each text message automatically. This could help us track the disease in a spatial resolution higher than the township level. ■

Box 1. Lessons learned.

Incorporate a reporting system using mobile phones into emergency preparation programmes.

Use mobile phones with global positioning system capacity to allow for more accurate tracking.

Apply appropriate restrictions to the use of phones.

Footnotes

Funding: Data collection, analysis, and preparation of this article were supported by a grant (No.30590370) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Watson JT, Gayer M, Connolly MA. Epidemics after natural disasters. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1–5. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qadri F, Khan AI, Faruque ASG, Begum YA, Chowdhury F, Nair GB, et al. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholera diarrhea, Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1104–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1107.041266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acute watery diarrhoea outbreak. Weekly Morbidity and Mortality Report 2005;1:6. Available from: http://www.who.int/hac/crises/international/pakistan_earthquake/sitrep/FINAL_WMMR_Pakistan_1_December_06122005.pdf [accessed on 4 June 2009].

- 4.Ma JQ, Yang GH, Shi XM. Disease surveillance based information technology platform in China. Ji Bing Jian Ce. 2006;21:1–3. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan WA. Can the ubiquitous power of mobile phones be used to improve health outcomes in developing countries? Global Health 2006; 2:9. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1524730&blobtype=pdf [accessed on 4 June 2009]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Sasaki D. Berhane Gebru: disease surveillance with mobile phones in Uganda. MobileActive.org, 30 July 2008. Available from: http://mobileactive.org/berhane-gebru-disease-surveillance-mobile-phones-uganda [accessed on 4 June 2009].

- 7.Soto G, Araujo-Castillo RV, Neyra J, Mundaca CC, Blazes DL. Challenges in the implementation of an electronic surveillance system in a resource-limited setting: Alerta, in Peru. BMC Proc. 2008;2(Suppl 3):S4. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-2-s3-s4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Safaie A, Mousavi SM, LaPorte RE, Goya MM, Zahraie M. Introducing a model for communicable diseases surveillance: cell phone surveillance (CPS). Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21:627–32. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-9033-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zamiska N. Indonesia goes wireless to overcome delays in bird-flu cases reports. Wall St J (East Ed), 17 August 2006; Sect. B:4.

- 10.Garnett JL, Kouzmin A. Communicating throughout Katrina: competing and complementary conceptual lenses on crisis communication. Public Adm Rev. 2007;67:S170–87. [Google Scholar]