Abstract

Moxidectin has been used safely as an antiparasitic in many animal species, including for the eradication of the mouse fur mite, Mycoptes musculinus. Although no side effects of moxidectin have previously been reported to occur in mice, 2 strains of the senescence-accelerated mouse (SAMP8 and SAMR1) sustained considerable mortality after routine prophylactic treatment. To investigate the mechanism underlying this effect, moxidectin toxicosis in these mice was evaluated in a controlled study. Moxidectin was applied topically (0.015 mg), and drug concentrations in both brain and serum were analyzed by using HPLC coupled with mass spectrometry. The moxidectin concentration in brain of SAMP8 mice was 18 times that in controls, and that in brain of SAMR1 mice was 14 times higher than in controls, whereas serum moxidectin concentrations did not differ significantly among the 3 strains. Because deficiency of the blood–brain barrier protein P-glycoprotein leads to sensitivity to this class of drugs in other SAM mice, Pgp immunohistochemistry of brain sections from a subset of mice was performed to determine whether this commercially available analysis could predict sensitivity to this class of drug. The staining analysis showed no difference among the strains of mice, indicating that this test does not correlate with sensitivity. In addition, no gross or histologic evidence of organ toxicity was found in brain, liver, lung, or kidney. This report shows that topically applied moxidectin at a standard dose accumulates in the CNS causing toxicosis in both SAMP8 and SAMR1 mice.

Abbreviations: BBB, blood–brain barrier; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; SAMP8, senescence-accelerated prone mice; SAMR1, senescence-accelerated resistant mice

A colony of senescence-accelerated prone (SAMP8) and senescence-accelerated resistant (SAMR1) mice experienced an episode of acute toxicosis from a routine dermal application of a commonly used veterinary endectocide, moxidectin. The SAM strains are an established murine model for accelerated aging and was first described in 1981 as a subpopulation of AKR mice.62 Although SAMR1 mice show normal aging characteristics, the SAMP8 strain has an early onset and advancement of senescence with changes in brain morphology as early as 4 wk of age and deterioration of learning at 4 mo.23,61,62,73 Although moxidectin has previously been used safely in more than 250 other strains of mice, all 17 treated SAMR1 and SAMP8 were found moribund or dead the day after prophylactic topical administration of moxidectin at a standard dose. Moxidectin is a macrocyclic lactone endectocide that is structurally related to the avermectins, which include ivermectin and selamectin.8 These drugs commonly are used as antiparasitics in laboratory animal facilities, and moxidectin specifically has been used in rats, mice, and hamsters.6,35,39,47,49

The mechanism of action for macrolide endectocides is usually parasite-specific, but toxicosis from this class of drugs has been reported in a variety of mammal species including laboratory animal rodents.20,29,59,74 These drugs primarily act as a potent agonist of glutamate- gated chloride ion channel activity in the CNS of the parasite, leading to paralysis and death. As an additional mode of action, these drugs enhance release of the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) at presynaptic neurons. Mammals are typically resistant to these effects because they lack glutamate-gated chloride ion channels and because mammalian GABA receptors occur only in the CNS. However, ivermectin sensitivity in collies and related dog breeds is well documented, and reports of increased ivermectin sensitivity in kittens, various cattle breeds, and dog-faced fruit bats also exist.10,31,58,63 The sensitivity in collies is dose-related, and even sensitive dogs can tolerate doses higher than those needed for heartworm prophylaxis of ivermectin and related drugs, including as much as 30 times the recommended dose of moxidectin.12,38,41-43,64 In contrast, ivermectin may be toxic at standard doses in adult mice of various transgenic strains, neonatal mice, and a subpopulation of CF1 mice.20,29,59 For example, ivermectin-sensitive mdr1a (mdr3)-deficient mice can tolerate a single dose at the low end of the published dose range (0.2 mg/kg), but this dose is toxic to some sensitive CF1 mice, especially with repeated administration.29,46,55 In addition, the wide margin of safety of ivermectin in nonsensitive animals has led to standard practice recommendations that may be toxic to ivermectin-sensitive strains, including a SAMR1 congenic mouse strain.20,24,55,59,74

Despite the structural similarities between moxidectin and ivermectin, reports of moxidectin toxicosis in mammals are rare in the literature and have only been reported with confirmed or suspected overdoses in horses, zebras, and dogs.5,14,17,21,25,60 Concerns about the safety of standard doses of moxidectin in dogs arose when a high incidence of life-threatening side effects, such as seizures and bleeding disorders, led a manufacturer to voluntarily recall an injectable moxidectin formulation approved for heartworm prevention (ProHeart6 Sustained Release Injectable for Dogs, Fort Dodge, Fort Dodge, IA) in 2004.9,26 Subsequent investigation indicated that residues of solvents used to make the product may have caused the side effects instead of the moxidectin itself, which prompted the FDA to allow a return of a reformulated product to the market. While ivermectin has been used since 1980, moxidectin was not introduced until 1997, and therefore the amount of time on the market may account for the disparity between the 2 drugs in the number of toxicity reports.

The mechanism of toxicity for ivermectin-sensitive collies and various strains of mice is a defect in the blood–brain barrier. The blood–brain barrier is formed by capillary endothelial cells and is partially maintained by the transmembrane transporter P-glycoprotein (Pgp). This transporter contributes to the blood–brain barrier by effluxing selective compounds back into the capillary lumen.55 Avermectin-sensitive dogs have a spontaneous deletion mutation in the MDR1 gene that encodes Pgp.2,33 Other studies showed ivermectin-sensitive CF1 mice to be deficient in Pgp in the intestinal and brain capillary epithelium. This deficiency was secondary to an insertion by an ecotropic murine leukemia virus in the mdr1a gene.22,29 Compared with controls, transgenic mice with a null mutation of the mdr1a gene are 50- to 100-fold more sensitive to oral ivermectin.55 Interestingly, the ivermectin toxicosis in the SAMR1.SAMP1-Apoa2c strain prompted investigations that revealed that their population of SAMR1 mice have the same mutation in the mdr1a gene as the ivermectin-sensitive CF1 mice, whereas their SAMP8 mice do not have this mutation.74 Once ivermectin has crossed the blood–brain barrier, the drug increases GABA release and subsequent postsynaptic receptor binding of GABA. Resulting clinical signs include tremors, weakness, blindness, incoordination, paresis, seizures, coma, and death.44 To determine whether the CNS was the target of the toxicity observed in our SAM mice, we performed a controlled study comparing serum and brain tissue levels of moxidectin after topical application by using the background strain, AKR, as a control. Because Pgp deficiency leads to neurotoxicity with other macrolide endectocides, we submitted samples to a commercial laboratory for Pgp immunohistochemistry. To our knowledge, this report is the first description of moxidectin toxicosis in rodents.

Materials and Methods

Humane care and use of animals.

Animals were housed in an AAALAC -accredited facility and in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.19 All research procedures involving animal use were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Emory University.

Housing and husbandry.

Mice were housed in polycarbonate shoebox cages with microisolation tops and corncob bedding in a room with a 12:12-h light:dark cycle. The original cohort of 17 mice treated prophylactically with moxidectin was fed a custom-formulated diet containing 150 ppm fenbendazole [Test Diet 1810129 [based on Lab Diet 5001], Purina Mills, Richmond, VA). In the controlled study, all groups of mice were fed standard rodent chow (Rodent Diet 5001, Purina Mills). The feed and reverse osmosis water were provided ad libitum throughout the experiment.

Mice.

SAMP8/TaHsd and SAMR1/TaHsd mice were obtained from the breeding colony at Emory University. This colony originated from 2 male and female mice of each strain (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) and has been maintained in the animal resource facilities since October 2005.

AKR/J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), from which the SAM strains derived originally,62 and Crl:CF1 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were used for controls as described in each section.

Moxidectin treatment and sample collection.

Cohort case.

Seventeen mice prophylactically treated with 0.015 mg (3 µL) moxidectin (Cydectin Pour-on, 5 mg/ml, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA) were found dead or moribund the next day. One moribund female SAMR1 4-wk-old and 1 male SAMP8 8-wk-old mouse were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and underwent complete necropsy, including gross and histopathologic analysis. Kidney, liver, heart, lungs, and coronal sections of brain were harvested and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin overnight. All tissues were submitted for histopathologic analysis, and brains were submitted for Pgp immunohistochemistry. Brain tissue from an 8-wk-old CF1 mouse that was clinically normal 24 h after moxidectin application was used as a control for the immunohistochemical analysis.

Controlled study.

For the study measuring tissue levels, five 5- to 14-wk-old female mice of each strain (SAMR1, SAMP8) and five 8-wk-old female AKR/J were treated topically with 0.015 mg moxidectin applied between the scapulae with an automatic pipettor. Mice were observed every 30 min for the development of neurologic signs, and the SAM mice were euthanized when either tremors or ataxia was noted. The AKR/J mice did not develop clinical signs but were euthanized concurrently with the clinically affected SAM mice. The first control and SAM mice were euthanized 2 h after moxidectin application, 8 of the 10 experimental mice and 3 of the controls were euthanized 2.5 to 4 h after application, and the remaining experimental and control mice were euthanized at 6.5 h after application. All mice were euthanized with CO2 inhalation immediately prior to sample collection. Necropsies were performed, and no gross lesions were noted. Half-brain sections and separated serum were frozen at −80 °C until the samples were shipped overnight for determining moxidectin concentrations.

Moxidectin assay.

Sample preparation.

Brain.

Sample (0.1 g) was weighed into a 50-mL French, squared homogenization vessel (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), homogenized with 20 mL acetonitrile for 1 min at 19,000 rpm by using a tissue homogenizer (UltraTurrax T25, IKA Labortechnik Tekmar, Cincinnati, OH), and centrifuged at 65 × g for 5 min (Centra 7, International Equipment, Needham, MA). An aliquot (18 mL) of the clear extract was transferred into a 250-mL separatory funnel, an equal amount of hexane was added, and the sample was shaken vigorously for 1 min. The acetonitrile layer was transferred into a glass disposable tube, evaporated to dryness by using a nitrogen evaporator (N-Evap Analytical Evaporator, Organomation Association, Berlin, MA) set at 60 °C, and redissolved in 200 μL acetonitrile:water (1:1, v/v). The mixture was vortexed for 10 s, sonicated for 2 min, and filtered through a 0.45-μm HPLC filter (Millipore, Milford, MA) into a small volume autosampler vial. All control and samples spiked with moxidectin standard were prepared in the same manner.

Serum

Serum (0.1 g) was weighed into a glass screw-cap test tube, 10 mL acetonitrile was added, and the sample was shaken vigorously by hand for exactly 2 min. The sample was centrifuged as described for brain, and a 9-mL aliquot was transferred into a glass tube, evaporated to dryness, redissolved in 180 µL acetonitrile:water (1:1, v/v), and filtered as described for brain.

HPLC and mass spectroscopy.

A high-performance liquid chromatograph (Microm BioResources, Auburn, CA) coupled with a hybrid triple-quadrupole–linear ion-trap mass spectrometer (model 4000 Q TRAP, Applied Biosystems–MDS Sciex, Concord, Canada) was used in all analyses. The analytical column measured 20 mm × 2.0 mm × 2 μm (Synergi MAX-RP, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). The injection volume was 20 μL. The mobile phase consisted of: (A) 10 mM ammonium acetate in 0.1% formic acid in water and (B) acetonitrile at a flow rate of 300 μL/min under a linear gradient of 50% B to 90% B over 5 min. Mass spectroscopy data were acquired in the positive-ion electrospray ionization mode by using the MRM scan function. The precursor ion of moxidectin was the [M+H]+ ion of m/z 640. Product ions of m/z 416, 478 (ion used for quantitation), 498, and 528 were obtained by using a collision energy of 25 eV, declustering potential of 30 V, collision exit potential of 13 V, and entrance potential of 10 V. The scan time for each MRM event was 200 ms.

Method validation.

The method was validated by analyzing control bovine brain samples (n = 5) containing moxidectin at 0.1 μg/g (100 ppb) and control bovine serum samples (n = 5) spiked with moxidectin at 0.05 μg/g (50 ppb). These positive controls were prepared by adding 100 μL of 1 μg/mL moxidectin standard to 1 g of negative, control bovine brain or 50 μL of the same standard to control bovine serum samples and analyzing the products as previously described.

Histopathologic and immunohistochemical analyses.

Tissues were embedded in paraffin wax, and serial sections (5 µm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathologic evaluation. Unstained sections of brain tissue were submitted to the Emory Medical Laboratory (Emory University Hospital, Atlanta, GA) for immunohistochemical analysis. Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated according to standard methods and stained by using an automated staining system (Autostainer, Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA). Slides were incubated in citrate buffer (pH 6) for 3 min at 120 °C and cooled for 10 min before immunostaining. Tissues were exposed to 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min and then incubated for 30 min with a monoclonal antibody to mouse Pgp (1:160, C219, Covance Research Products, Dedham, MA). The primary antibody was detected by using 2-step system involvingt a polymer labeled with horseradish peroxidase and conjugated with secondary antibodies (EnVision, Dako). Slides were incubated with the labeled polymer for 30 min, with diaminobenzidine as a chromogen for 5 min, and with hematoxylin as a counterstain for 15 min. These incubations were performed at room temperature, and sections were washed with Tris-buffered saline between reagents.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SigmaStat 2.03 software package (Jandel, San Rafael, CA). A Two-Way ANOVA with a repeated measure on 1 factor was used to compare moxidectin concentrations with a post-hoc Tukey's test. A P < 0.05 value was considered significant.

Results

Clinical signs.

Cohort case.

Within 24 h of application of 0.015 mg moxidectin as a routine prophylactic to 17 mice, all of the mice were found either dead or severely moribund. The surviving mice were hypothermic and barely responsive to toe pinch.

Controlled study.

When 0.015 mg moxidectin was administered in the controlled study, 100% of the SAMR1 and SAMP8 mice developed clinical signs within 2 to 6.5 h of moxidectin application. Clinical signs included ataxia and tremors, particularly head tremors although whole body tremors also occurred. None of the AKR/J mice (controls) developed any clinical signs.

Tissue levels of moxidectin (controlled study).

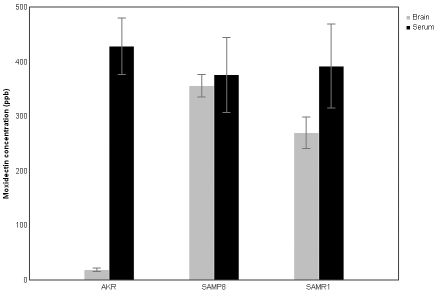

The moxidectin concentration (mean ± SEM) in the brain tissue of SAMR1 mice (270 ± 28.2 ppb) and SAMP8 mice (356 ± 20.4 ppb) was significantly higher than for the AKR/J mice (19 ± 3.4 ppb; F[2,12] = 4.008; P = 0.046), indicating that the drug entered and accumulated in the CNS of the SAM mice. AKR/J mice had significantly higher moxidectin levels in the serum (428 ± 52 ppb) than in the brain (19 ± 3.4 ppb; F[1,12] = 23.768; P < 0.001), presumably reflecting an intact blood–brain barrier. Serum levels of moxidectin did not differ among the 3 strains. In addition, serum and brain concentrations of moxidectin did not differ in the SAMR1 or SAMP8 mice (Figure 1), showing that drug had equilibrated between serum and CNS.

Figure 1.

Tissue levels of moxidectin as determined by LC–MS/MS. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5). The brain tissue levels were significantly higher in both of the SAM strains than in the AKR/J mice. Serum moxidectin concentrations were not significantly different among the 3 strains.

Quantitation of moxidectin in brain and serum samples by using the electrospray ionization HPLC–mass spectroscopy technique was affected by ion suppression. Therefore, it was essential to perform quantitation by using standards in matrices that matched those of the samples. The standard curves in both matrix types followed linear regression with r2 values typically in the range of 0.999. Five replicate samples of brain homogenate containing moxidectin at 0.1 μg/g (100 ppb) yielded an average recovery of 108% (9% coefficient of variation; 5 replicate samples of serum spiked with 0.05 μg/g moxidectin (50 ppb) gave an average recovery of 95% (3% coefficient of variation.

Histopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis.

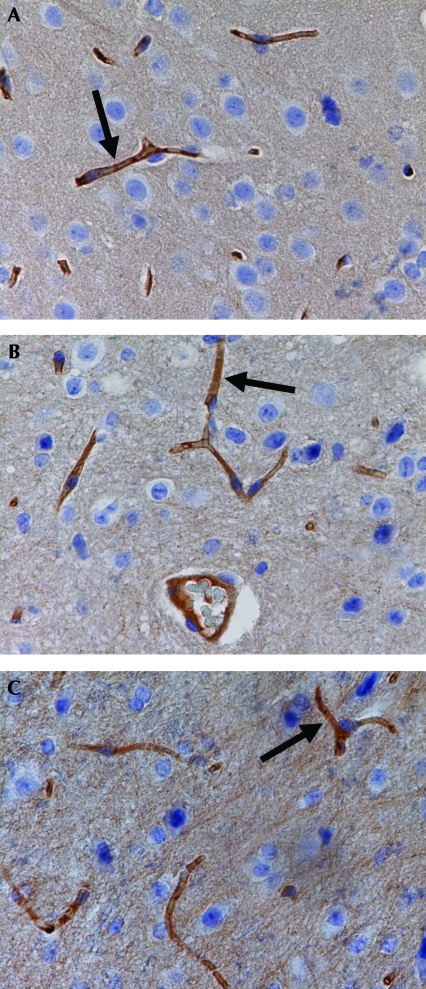

No significant gross or histologic lesions were found in the kidney, liver, heart, lungs, and brain of SAMP8 and SAMR1 mice. Immunolabeling was positive for Pgp and similarly localized in the capillary endothelial cells of SAMR1, SAMP8, and CF1 mice (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical staining of brain sections by using C219 monoclonal antibody: (A) a CF1 mouse that had no signs of toxicity after moxidectin application and (B) SAMR1 and (C) SAMP8 mice that were found moribund after moxidectin application. The black arrows indicate positive dark-brown staining in the capillary endothelial cells. No difference in P-glycoprotein expression was observed in the capillaries of the SAMP8, SAMR1, and CF1 mice). Hematoxylin counterstain; magnification, ×400 (×40 objective and ×10 ocular).

Discussion

This study shows that moxidectin caused neurotoxicity in SAMP8 and SAMR1 strains of mice even though the drug was used at recommended doses. After topical administration, SAM mice exhibited clinical signs that included ataxia and trembling, and analysis showed that their brain tissue contained significantly higher moxidectin concentrations than that in the control (AKR/J) mice. These clinical signs are similar to those previously reported in circumstances of increased levels of macrolide endectocides in the CNS of mice and other species.25,32,44,55 During the controlled study, the mice were not allowed to progress to clinical signs worsening beyond tremors and ataxia for humane reasons. However, considering that moxidectin was lethal for 100% of the original cohort of mice, the toxicosis induced experimentally likely would have been fatal also. The mortality was not attributable to the specific batch of moxidectin because it was used to treat mice of other strains that remained clinically normal. The index mice also were receiving fenbendazole-containing chow, but that feed had been fed to other SAMP8 mice, as well as to many other strains in the facility, and no clinical signs or mortality were observed. In addition, fenbendazole toxicosis at standard doses in rodents has not been reported, nor does this drug cause neurologic signs at toxic levels in other species.71 Importantly, the clinical signs observed in our study occurred at the same dose previously published for mice.35,49 Our hypothesis that moxidectin accumulated in the CNS of the SAM mice was confirmed by high concentrations in brain tissue from both SAMP8 and SAMR1 strains—concentrations that were 18 and 14 times, respectively, higher than those in AKR/J mice. These results are consistent with findings from studies of ivermectin-sensitive dogs and mice, in which drug levels were significantly higher in the brain compared with control animals.48,55

We observed no significant histopathologic lesions in mice with moxidectin toxicosis, a finding consistent with other studies in avermectin-sensitive mice. One study in ivermectin-sensitive CF1 mice demonstrated selective neuronal degeneration in the CA3 region of the hippocampus after ivermectin treatment, but most studies of sensitive mice report no lesions associated with toxicosis.22,28,29 The discrepancy between studies that have found histologic lesions and those that have not could be due to the difficulty of finding discrete brain lesions or to a dose-related effect, because the mice that had brain lesions received an amount that is 10 times the recommended dose of ivermectin. In our study, hippocampus of both SAMP8 and SAMR1 strains was evaluated, but no lesions were seen. In addition, the SAM strains lacked histologic signs of toxicosis to other organs, but the acute toxicosis may not have allowed adequate time for histologic lesions to develop, so the possibility of toxicity to other organs cannot be discounted.

The brain concentrations of moxidectin in the SAM mice were significantly higher than in control mice, whereas the serum concentrations were similar. These results suggest that the increased brain levels are not secondary to elevated serum levels but instead are due to a mechanism that specifically allows CNS accumulation. In contrast to our findings, both mdr1a-deficient and ivermectin-sensitive CF1 mice had serum ivermectin levels that were elevated relative to those of controls but at a magnitude much lower than that seen in brain tissue.27,29,55 These discrepancies may reflect the fact that an oral route of administration instead of dermal was used. Increased serum levels might indicate increased oral bioavailability of the drug in mice with a deficiency in intestinal Pgp, particularly because there was no difference in serum levels of Pgp-deficient mice and controls when ivermectin was administered intravenously.27 Although our study analyzed acute levels, findings were consistent with those from studies of ivermectin-sensitive collies in which serum ivermectin levels were similar to those of nonsensitive collies during the first 8 h and for 21 d after ivermectin administration.63 The inconsistency of serum results could be related to a variety of causes from dose, administration, drug formulation, or even reflect species differences in Pgp distribution or drug metabolism. Regardless of the mechanism controlling the serum levels, previous studies have consistently documented higher brain levels of the drugs relative to serum concentrations in sensitive animals.

The differential accumulation of moxidectin in the CNS suggests a loss of selectivity in the blood–brain barrier. We considered Pgp deficiency as a potential mechanism not only because this is a mechanism of toxicity for ivermectin in some SAM strains, but also because moxidectin is a Pgp substrate, and Pgp inhibitors increase its bioavailability as they do for ivermectin.11,30,74 Mice have 3 mdr genes, mdr1a (mdr3), mdr1b, and mdr 2. The product of mdr2 genes are localized to the liver, whereas mdr1 Pgp is located in many tissues, including as brain and intestine.32,55 Mdr1a and mdr1b Pgp are very similar but do not have identical drug transport abilities.55 The primary antibody used for the immunohistochemistry antibodies detects all 3 of these gene products, and the assays were positive for the presence of Pgp in the brain capillaries. Our immunochemical analysis used the same primary antibody, the monoclonal antibody C219, as did previous reports and produced staining specific for the capillary endothelium as expected.29,55,65 However, the staining in the current study was not quantified, as done in previous studies. Although some CF1 mice that were insensitive to avermectins had only slight positive staining,29 evaluating a larger number of SAM mice could reveal less Pgp staining than in controls. Alternatively, the SAM mice could have nonfunctional Pgp that is nonetheless still detectable by immunohistochemistry. A functional assay may indicate that Pgp is present but nonfunctional; alternatively quantitative analysis may reveal decreased amounts of Pgp sufficient to reduce the effectiveness of the blood–brain barrier and lead to positive staining.

We suspect that a Pgp defect may be the cause for the toxicosis observed in our study, and that this particular commercial technique is too sensitive or not specific enough to demonstrate the deficiency. Pgp deficiency has recently been discovered in 7 SAM strains, including SAMR1, by using PCR to detect a mutation in the mdr1a gene.74 The SAMP8 mice in that study did not have the mutation, and they could tolerate high doses of ivermectin with no clinical signs. This tolerance indicates that the avermectin sensitivity should not be associated with the typical aging related pathology in the SAMP8 strain. In addition, the moxidectin sensitivity noted in our population of SAMP8 mice likely indicates a difference between subpopulations in sensitivity to these drugs. This variation is similar to that in CF1 mice, where approximately 25% of the population was ivermectin-sensitive.70 A Pgp deficiency cannot be discounted without further studies, and this immunohistochemistry test would not easily predict a deficiency. PCR, restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, and Western blot analysis have been used to confirm Pgp gene abnormalities in dogs and mice and might be applied to various SAM populations.2,22,29,51,70,74

Another possibility for our results is that both strains have a mutation that affects a component of the blood–brain barrier that is not associated with senescence-related pathology. The integrity of the blood–brain barrier is maintained not only by Pgp but also by highly impermeable tight junctions, a lack of fenestrations, and a scarcity of pinocytotic vesicles of endothelial cells; a compromise of any of these systems is a potential mechanism for neurotoxicity.66,69 Toxicosis in normal neonatal mice is partially due to an incomplete blood–brain barrier, which does not form until 10 to 13 d of age in mice, and Pgp does not approximate adult levels until 21 d.59,65 The mice in the present study were all weaned and likely had formed a complete blood–brain barrier given their age. To our knowledge, avermectin sensitivity secondary to abnormalities in the blood–brain barrier unrelated to Pgp have not been reported to occur in mammals, but a few studies have documented particular mutant mouse strains that have increased blood–brain barrier permeability.1,16,50 In particular, the blood–brain barrier deteriorates with age and is a postulated mechanism for age-related deficits in learning and memory, a scenario that is consistent with the numerous studies that show age-related deterioration in the blood–brain barrier in old SAMP8 mice, but these studies failed to find similar deficiencies in young SAMP8 mice or SAMR1 mice of any age.3,4,45,67-69 The incomplete blood–brain barrier in the periventricular white matter in both SAMP8 and SAMR1 mice likely is a normal phenomenon because similar increased permeability is noted in normal C3H and DBA/2 mice after intravenous injections with horseradish peroxidase.66,69 Young SAMP8 mice do have some abnormalities in brain physiology, including increased oxidative stress and dysfunction of mitochondria and astrocytes, but these abnormalities do not explain the results in the control strain, SAMR1, or the ivermectin tolerance in another SAMP8 population.7,13,15,36,37,54 Our study used young SAMP8 and SAMR1 mice, and we do not believe the increased blood–brain barrier permeability to be the result of the aging process. Finally, toxicosis (including neurologic signs) from drugs in this class has been noted in dogs and humans with high parasite burdens, but no parasites were found in our mice on necropsy or histology.40,46 Considering the controlled environment and lack of evidence of parasites, toxicosis due to interactions of drug and high parasite burden is an unlikely cause of the morbidity and mortality.

Although our results do not confirm Pgp deficiency in these strains, they do clearly show that moxidectin crossed the blood–brain barrier, a feature that may have important implications for the use of other drugs that are normally restricted by the blood–brain barrier in these mice. Toxicity associated with various medications is well documented in animals with a compromised blood–brain barrier, such as toxicosis from chemotherapeutic agents in dogs with MDR1 mutations.34 In addition, collies are overrepresented in canine cases of neurotoxicity with normal doses of loperamide.18,53 Mice with a disruption in the mdr1a gene are not only more sensitive to many drugs, including vinblastine, digoxin, cyclosporine A, dexamethsone, and morphine, but also have an increased uptake of bilirubin.55-57,72 The list of MDR1 Pgp substrates in humans is even more extensive and includes antibiotics, antiemetics, and antihistamines.52,55 SAM mice have a potentially novel mechanism for a blood–brain barrier defect, and possible toxicities should be considered when administering drugs to these strains.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Mauricio Rojas for allowing us to use his mice, Minida Dowdy for her technical assistance and information regarding the breeding colony, and Dr Ana Patricia García for her assistance with the photomicrographs. In addition, we thank Ms Elizabeth Tor (California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory System) for her technical assistance with the analysis of moxidectin in brain and serum.

References

- 1.Araya R, Kudo M, Kawano M, Ishii K, Hashikawa T, Iwasato T, Itohara S, Terasaki T, Oohira A, Mishina Y, Yamada M. 2008. BMP signaling through BMPRIA in astrocytes is essential for proper cerebral angiogenesis and formation of the blood–brain barrier. Mol Cell Neurosci 38:417–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baars C, Leeb T, von Klopmann T, Tipold A, Potschka H. 2008. Allele-specific polymerase chain reaction diagnostic test for the functional MDR1 polymorphism in dogs. Vet J 177:394–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banks WA, Farr SA, Morley JE, Wolf KM, Geylis V, Steinitz M. 2007. Antiamyloid β protein antibody passage across the blood–brain barrier in the SAMP8 mouse model of Alzheimer disease: an age-related selective uptake with reversal of learning impairment. Exp Neurol 206:248–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banks WA, Moinuddin A, Morley JE. 2001. Regional transport of TNFα across the blood-brain barrier in young ICR and young and aged SAMP8 mice. Neurobiol Aging 22:671–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beal MW, Poppenga RH, Birdsall WJ, Hughes D. 1999. Respiratory failure attributable to moxidectin intoxication in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 215:1813–1817 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beco L, Petite A, Olivry T. 2001. Comparison of subcutaneous ivermectin and oral moxidectin for the treatment of notoedric acariasis in hamsters. Vet Rec 149:324–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiba Y, Shimada A, Kumagai N, Yoshikawa K, Ishii S, Furukawa A, Takei S, Sakura M, Kawamura N, Hosokawa M. 2008. The senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM): a higher oxidative stress and age-dependent degenerative diseases model. Neurochem Res [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Courtney CH, Roberson EL. 1995. Chemotherapy of parasitic diseases Adams HR. Veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics. Ames (IA): Iowa State University Press [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curry-Galvin E. 2005. The ProHeart debate. J Am Vet Med Assoc 226:1280–1281 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeMarco JH, Heard DJ, Fleming GJ, Lock BA, Scase TJ. 2002. Ivermectin toxicosis after topical administration in dog-faced fruit bats (Cynopterus brachyotis). J Zoo Wildl Med 33:147–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dupuy J, Lespine A, Sutra JF, Alvinerie M. 2006. Fumagillin, a new P-glycoprotein-interfering agent able to modulate moxidectin efflux in rat hepatocytes. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 29:489–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fassler PE, Tranquilli WJ, Paul AJ, Soll MD, DiPietro JA, Todd KS. 1991. Evaluation of the safety of ivermectin administered in a beef-based formulation to ivermectin-sensitive collies. J Am Vet Med Assoc 199:457–460 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujibayashi Y, Yamamoto S, Waki A, Konishi J, Yonekura Y. 1998. Increased mitochondrial DNA deletion in the brain of SAMP8, a mouse model for spontaneous oxidative stress brain. Neurosci Lett 254:109–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallagher AE, Grant DC, Noftsinger MN. 2008. Coma and respiratory failure due to moxidectin intoxication in a dog. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 18:81–85 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Matas S, Gutierrez-Cuesta J, Coto-Montes A, Rubio-Acero R, Diez-Vives C, Camins A, Pallas M, Sanfeliu C, Cristofol R. 2008. Dysfunction of astrocytes in senescence-accelerated mice SAMP8 reduces their neuroprotective capacity. Aging Cell 7:630–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hafezi-Moghadam A, Thomas KL, Wagner DD. 2007. ApoE deficiency leads to a progressive age-dependent blood–brain barrier leakage. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292:C1256–C1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hautekeete LA, Khan SA, Hales WS. 1998. Ivermectin toxicosis in a zebra. Vet Hum Toxicol 40:29–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hugnet C, Cadore JL, Buronfosse F, Pineau X, Mathet T, Berny PJ. 1996. Loperamide poisoning in the dog. Vet Hum Toxicol 38:31–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington (DC): National Academy Press [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson TA, Hall JE, Boivin GP, Lou W, Stedelin OHJR. 1998. Ivermectin toxicity in multiple transgenic mouse line. Lab Anim Pract 31:37–41 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson PJ, Mrad DR, Schwartz AJ, Kellam L. 1999. Presumed moxidectin toxicosis in three foals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 214:678–680 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jun K, Lee SB, Shin HS. 2000. Insertion of a retroviral solo long terminal repeat in mdr3 locus disrupts mRNA splicing in mice. Mamm Genome 11:843–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawamata T, Akiguchi I, Maeda K, Tanaka C, Higuchi K, Hosokawa M, Takeda T. 1998. Age-related changes in the brains of senescence-accelerated mice (SAM): association with glial and endothelial reactions. Microsc Res Tech 43:59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerrick GP, Hoskins DE, Ringler DH. 1995. Eradication of pinworms from rats by using ivermectin in the drinking water. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 34:78–79 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan SA, Kuster DA, Hansen SR. 2002. A review of moxidectin overdose cases in equines from 1998 through 2000. Vet Hum Toxicol 44:232–235 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuehn BM. 2004. Fort Dodge recalls ProHeart 6, citing FDA safety concerns. Advisory committee to review FDA findings. J Am Vet Med Assoc 225:1157–1158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwei GY, Alvaro RF, Chen Q, Jenkins HJ, Hop CE, Keohane CA, Ly VT, Strauss JR, Wang RW, Wang Z, Pippert TR, Umbenhauer DR. 1999. Disposition of ivermectin and cyclosporin A in CF1 mice deficient in mdr1a P-glycoprotein. Drug Metab Dispos 27:581–587 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lankas G, Gordon L. 1989. Toxicology Campbell WC. Ivermectin and abamectin. New York (NY): Springer-Verlag [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lankas GR, Cartwright ME, Umbenhauer D. 1997. P-glycoprotein deficiency in a subpopulation of CF1 mice enhances avermectin-induced neurotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 143:357–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lespine A, Martin S, Dupuy J, Roulet A, Pineau T, Orlowski S, Alvinerie M. 2007. Interaction of macrocyclic lactones with P-glycoprotein: structure–affinity relationship. Eur J Pharm Sci 30:84–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis DT, Merchant SR, Neer TM. 1994. Ivermectin toxicosis in a kitten. J Am Vet Med Assoc 205:584–586 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marques-Santos LF, Bernardo RR, de Paula EF, Rumjanek VM. 1999. Cyclosporin A and trifluoperazine, two resistance-modulating agents, increase ivermectin neurotoxicity in mice. Pharmacol Toxicol 84:125–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mealey KL, Bentjen SA, Gay JM, Cantor GH. 2001. Ivermectin sensitivity in collies is associated with a deletion mutation of the mdr1 gene. Pharmacogenetics 11:727–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mealey KL, Northrup NC, Bentjen SA. 2003. Increased toxicity of P-glycoprotein-substrate chemotherapeutic agents in a dog with the MDR1 deletion mutation associated with ivermectin sensitivity. J Am Vet Med Assoc 223: 1453–1455, 1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mook DM, Benjamin KA. 2008. Use of selamectin and moxidectin in the treatment of mouse fur mites. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 47:20–24 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mori A, Utsumi K, Liu J, Hosokawa M. 1998. Oxidative damage in the senescence-accelerated mouse. Ann N Y Acad Sci 854:239–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishikawa T, Takahashi JA, Fujibayashi Y, Fujisawa H, Zhu B, Nishimura Y, Ohnishi K, Higuchi K, Hashimoto N, Hosokawa M. 1998. An early stage mechanism of the age-associated mitochondrial dysfunction in the brain of SAMP8 mice; an age-associated neurodegeneration animal model. Neurosci Lett 254:69–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novotny MJ, Krautmann MJ, Ehrhart JC, Godin CS, Evans EI, McCall JW, Sun F, Rowan TG, Jernigan AD. 2000. Safety of selamectin in dogs. Vet Parasitol 91:377–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oge H, Ayaz E, Ide T, Dalgic S. 2000. The effect of doramectin, moxidectin, and netobimin against natural infections of Syphacia muris in rats. Vet Parasitol 88:299–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orion E, Matz H, Wolf R. 2005. The life-threatening complications of dermatologic therapies. Clin Dermatol 23:182–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paul AJ, Hutchens DE, Firkins LD, Borgstrom M. 2004. Dermal safety study with imidacloprid–moxidectin topical solution in the ivermectin-sensitive collie. Vet Parasitol 121:285–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paul AJ, Todd KS, Jr, Acre KE, Sr, Plue RE, Wallace DH, French RA, Wallig MA. 1991. Efficacy of ivermectin chewable tablets and two new ivermectin tablet formulations against Dirofilaria immitis larvae in dogs. Am J Vet Res 52:1922–1923 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paul AJ, Tranquilli WJ, Hutchens DE. 2000. Safety of moxidectin in avermectin-sensitive collies. Am J Vet Res 61:482–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paul AJ, Tranquilli WJ, Seward RL, Todd KS, Jr, DiPietro JA. 1987. Clinical observations in collies given ivermectin orally. Am J Vet Res 48:684–685 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pelegri C, Canudas AM, del Valle J, Casadesus G, Smith MA, Camins A, Pallas M, Vilaplana J. 2007. Increased permeability of blood–brain barrier on the hippocampus of a murine model of senescence. Mech Ageing Dev 128:522–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plumb DC. 2005. Plumb's veterinary drug handbook. Ames (IA): Wiley-Blackwell [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pollicino P, Rossi L, Rambozzi L, Farca AM, Peano A. 2008. Oral administration of moxidectin for treatment of murine acariosis due to Radfordia affinis. Vet Parasitol 151:355–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pulliam JD, Seward RL, Henry RT, Steinberg SA. 1985. Investigating ivermectin toxicity in collies. Vetenary Medicine 80:33–40 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pullium JK, Brooks WJ, Langley AD, Huerkamp MJ. 2005. A single dose of topical moxidectin as an effective treatment for murine acariasis due to Myocoptes musculinus. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 44:26–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reuss B, Dono R, Unsicker K. 2003. Functions of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 2 and FGF5 in astroglial differentiation and blood–brain barrier permeability: evidence from mouse mutants. J Neurosci 23:6404–6412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roulet A, Puel O, Gesta S, Lepage JF, Drag M, Soll M, Alvinerie M, Pineau T. 2003. MDR1-deficient genotype in Collie dogs hypersensitive to the P-glycoprotein substrate ivermectin. Eur J Pharmacol 460:85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sakaeda T, Nakamura T, Okumura K. 2002. MDR1 genotype-related pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Biol Pharm Bull 25:1391–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sartor LL, Bentjen SA, Trepanier L, Mealey KL. 2004. Loperamide toxicity in a collie with the MDR1 mutation associated with ivermectin sensitivity. J Vet Intern Med 18:117–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sato E, Oda N, Ozaki N, Hashimoto S, Kurokawa T, Ishibashi S. 1996. Early and transient increase in oxidative stress in the cerebral cortex of senescence-accelerated mouse. Mech Ageing Dev 86:105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schinkel AH, Smit JJ, van Tellingen O, Beijnen JH, Wagenaar E, van Deemter L, Mol CA, van der Valk MA, Robanus-Maandag EC, te Riele HP, Berns AJ, Borst P. 1994. Disruption of the mouse mdr1a P-glycoprotein gene leads to a deficiency in the blood–brain barrier and to increased sensitivity to drugs. Cell 77:491–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schinkel AH, Wagenaar E, Mol CA, van Deemter L. 1996. P-glycoprotein in the blood–brain barrier of mice influences the brain penetration and pharmacological activity of many drugs. J Clin Invest 97:2517–2524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schinkel AH, Wagenaar E, van Deemter L, Mol CA, Borst P. 1995. Absence of the mdr1a P-glycoprotein in mice affects tissue distribution and pharmacokinetics of dexamethasone, digoxin, and cyclosporin A. J Clin Invest 96:1698–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seaman JT, Eagleson JS, Carrigan MJ, Webb RF. 1987. Avermectin B1 toxicity in a herd of Murray Grey cattle. Aust Vet J 64:284–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skopets B, Wilson RP, Griffith JW, Lang CM. 1996. Ivermectin toxicity in young mice. Lab Anim Sci 46:111–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Snowden NJ, Helyar CV, Platt SR, Penderis J. 2006. Clinical presentation and management of moxidectin toxicity in two dogs. J Small Anim Pract 47:620–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takeda T, Hosokawa M, Higuchi K. 1997. Senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM): a novel murine model of senescence. Exp Gerontol 32:105–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takeda T, Hosokawa M, Takeshita S, Irino M, Higuchi K, Matsushita T, Tomita Y, Yasuhira K, Hamamoto H, Shimizu K, Ishii M, Yamamuro T. 1981. A new murine model of accelerated senescence. Mech Ageing Dev 17:183–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tranquilli WJ, Paul AJ, Seward RL. 1989. Ivermectin plasma concentrations in collies sensitive to ivermectin-induced toxicosis. Am J Vet Res 50:769–770 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tranquilli WJ, Paul AJ, Todd KS. 1991. Assessment of toxicosis induced by high-dose administration of milbemycin oxime in collies. Am J Vet Res 52:1170–1172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tsai CE, Daood MJ, Lane RH, Hansen TW, Gruetzmacher EM, Watchko JF. 2002. P-glycoprotein expression in mouse brain increases with maturation. Biol Neonate 81:58–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ueno M, Akiguchi I, Hosokawa M, Kotani H, Kanenishi K, Sakamoto H. 2000. Blood–brain barrier permeability in the periventricular areas of the normal mouse brain. Acta Neuropathol 99:385–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ueno M, Akiguchi I, Yagi H, Naiki H, Fujibayashi Y, Kimura J, Takeda T. 1993. Age-related changes in barrier function in mouse brain. I. Accelerated age-related increase of brain transfer of serum albumin in accelerated senescence prone SAM-P/8 mice with deficits in learning and memory. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 16:233–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ueno M, Sakamoto H, Kanenishi K, Onodera M, Akiguchi I, Hosokawa M. 2001. Ultrastructural and permeability features of microvessels in the hippocampus, cerebellum, and pons of senescence-accelerated mice (SAM). Neurobiol Aging 22:469–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ueno M, Sakamoto H, Kanenishi K, Onodera M, Akiguchi I, Hosokawa M. 2001. Ultrastructural and permeability features of microvessels in the periventricular area of senescence-accelerated mice (SAM). Microsc Res Tech 53:232–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Umbenhauer DR, Lankas GR, Pippert TR, Wise LD, Cartwright ME, Hall SJ, Beare CM. 1997. Identification of a P-glycoprotein-deficient subpopulation in the CF1 mouse strain using a restriction fragment length polymorphism. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 146:88–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Villar D, Cray C, Zaias J, Altman NH. 2007. Biologic effects of fenbendazole in rats and mice: a review. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 46:8–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Watchko JF, Daood MJ, Hansen TW. 1998. Brain bilirubin content is increased in P-glycoprotein-deficient transgenic null mutant mice. Pediatr Res 44:763–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yagi H, Katoh S, Akiguchi I, Takeda T. 1988. Age-related deterioration of ability of acquisition in memory and learning in senescence accelerated mouse: SAMP/8 as an animal model of disturbances in recent memory. Brain Res 474:86–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang G, Zhang B, Fu X, Tomozawa H, Matsumoto K, Higuchi K, Mori M. 2008. Senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM) strains have a spontaneous mutation in the Abcb1a gene. Exp Anim 57:413–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]