Abstract

To date, most peptide-based vaccines evaluated for the treatment of cancer have consisted of one or few peptides. However, as a greater number of peptide antigens become available for use in experimental therapies, it is important to establish the feasibility of combining multi-peptide reagents as individual peptide mixtures. We have found that mixtures of up to 12 peptides can be analyzed accurately for identity, purity, and stability (for at least 5 years) using a combination of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectrometry and these complex peptide mixtures have been acceptable for use in human clinical trials. We have also identified some specific concerns for degradation products that should be considered in multipeptide vaccine preparation and follow-up quality assurance studies. Results from these analyses have implications for changing the way peptide-based vaccines are manufactured and demonstrate that multi-peptide vaccines are reliable reagents for use in peptide-based immune therapies.

Keywords: peptide vaccine, immune therapy, stability testing

1.0 Introduction

CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) and CD4+ helper T lymphocytes (HTL) play a critical role in the control of tumor progression, and approaches to induce tumor-specific immune responses have focused on identifying efficient ways to activate and to amplify these T cell populations against tumor antigens. CD8+ CTL recognize peptide antigens presented in the context of class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules whereas CD4+ HTL recognize peptide antigens presented in the context of class II MHC molecules. Thus, the identification of the peptide targets of CTL and HTL has been of great benefit for the design and development of active specific immune therapies directed towards the in vivo activation of tumor specific T cells. Peptide antigens for these T cells derived from tumor-associated proteins have been characterized, and these peptides are presented by one or more HLA class I or class II alleles (1;2).

Identification of peptide epitopes for tumor-specific CTL and HTL provides an opportunity to create vaccines that can be evaluated directly in terms of the CTL and HTL responses to the purified immunizing antigen. Despite the large number of cancer-associated peptide antigens now identified, only a small subset has been tested in vivo for safety and immunogenicity. Among those studied in vivo, many are immunogenic and safe (3–11).

Solid tumors often contain a heterogeneous population of cells with respect to protein expression. Thus, multi-peptide vaccines may have greater therapeutic potential than single peptide vaccines for most patients with cancer. In several prior clinical studies involving multi-peptide vaccines, small numbers of peptides were administered, and each was administered at a distinct site (12;13). However, as the number of relevant peptides available for use continues to grow, vaccination at multiple separate sites becomes less feasible. Thus, we have developed multi-peptide vaccines and have administered them as mixtures of up to 12 peptides (2). We have demonstrated that co-administration of such mixtures can induce immune responses to multiple peptides, and that competition for binding MHC molecules does not appear to limit the immunogenicity of individual peptides (14;15). Administration of a multi-peptide vaccine as a single mixture offers many advantages including: 1) injection of a limited volume of vaccine into a patient, 2) limiting the number of skin sites with the local toxicity of injection site reactions, 3) limiting chance of error and contamination with the preparation of one versus multiple peptide preparations.

However, there are several issues to consider when combining multiple peptides in a single mixture. These include the ability to characterize the mixtures adequately for regulatory purposes, and the stability of these mixtures over time. In this report, we present our experience over a decade with preparation of multipeptide vaccines, with details on peptide-specific stability issues, and with explanation of approaches for quality assurance testing that has been acceptable to the US Food and Drug Administration for clinical trial use. These data may be useful guidance for groups pursuing multipeptide vaccines for the treatment of cancer or other uses of mixtures of peptides or other small molecules for clinical benefit.

2.0 Materials and Methods

2.1 Peptides

Peptides were synthesized and purified either by the University of Virginia Biomolecular Research Laboratory, or under GMP conditions by Multiple Peptide Systems (now NeoMPS, San Diego, CA). Each was synthesized with a free amide NH2 terminus and free acid COOH terminus and provided as a lyophilized powder. The purity of each peptide component exceeded 90% of the peptide species derived from that synthesis. However, variants of the original peptide may have included incomplete products of synthesis, minor degradation products due to oxidation of methionine residues and other minor changes. We have also observed dimerization of cysteine-containing peptides, but this appeared to be preventable by storage at ≤ −70°C. Minor variants were tolerated as long as the intended peptide represented at least 75% of the peptide species derived from that synthesis. The described vaccine mixtures consisted of the peptides listed in Tables 1–3, and these are the primary focus of the present report due to longer experience with them. Additional peptide vaccines utilized by our group include the following:

Table 1.

Twelve melanoma peptide (12-MP) vaccine: MELITAC 12.0

| Allele | Sequence | Epitope |

|---|---|---|

| HLA-A1 | DAEKSDICTDEY | Tyrosinase 240–251 a |

| SSDYVIPIGTY | Tyrosinase 146–156 | |

| EADPTGHSY | MAGE-A1 161–169 | |

| EVDPIGHLY | MAGE-A3 168–176 | |

| HLA-A2 | YMDGTMSQV | Tyrosinase 369–377 b |

| IMDQVPFSV | gp100 209–217c | |

| YLEPGPVTA | gp100 280–288 | |

| GLYDGMEHL | MAGE-A10 254–262 | |

| HLA-A3 | ALLAVGATK | gp100 17–25 |

| LIYRRRLMK | gp100 614–622 | |

| SLFRAVITK | MAGE-A1 96–104 | |

| ASGPGGGAPR | NY-ESO-1 53–62 |

(substitution of S for C at residue 244)

(post-translational change of N to D at residue 371)

(209-2M, substitution of M for T at residue 210)

Table 3.

Six melanoma helper peptide (6-MHP) vaccine – MELITAC 0.6

| Allele | Sequence | Epitope |

|---|---|---|

| HLA-DR4 | AQNILLSNAPLGPQFP | Tyrosinase56–70a |

| HLA-DR15 | FLLHHAFVDSIFEQWLQRHRP | Tyrosinase386–406 |

| HLA-DR4 | RNGYRALMDKSLHVGTQCALTRR | Melan-A/MART-151–73 |

| HLA-DR11 | TSYVKVLHHMVKISG | MAGE-3281–295 |

| HLA-DR13 | LLKYRAREPVTKAE | MAGE-1,2,3,6121–134 |

| HLA-DR1 & - DR4 | WNRQLYPEWTEAQRLD | gp10044–59 |

An alanine residue was added to the N-terminus to prevent cyclization

Modified tetanus peptide - Peptide-tet

AQYIKANSKFIGITEL (p2830–844; an alanine residue was added to the N-terminus to prevent cyclization) (16)

4 Colon Peptides

HLA-A2 restricted: KIFGSLAFL (Her-2/neu 369–377); YLSGADLNL (CEA571–579; asparagine to aspartic acid substitution at position 576); HLA-A3 restricted: VLRENTSPK (Her-2/neu754–762); and HLFGYSWYK (CEA27–35).

5 Ovarian Peptides (10)

HLA-A1 restricted: EADPTGHSY (MAGE-A1161–169); HLA-A2 restricted: EIWTHSYKV (FBP191–199); KIFGSLAFL (Her-2/neu369–377); HLA-A3 restricted: SLFRAVITK (MAGE-A196–104); and VLRENTSPK (Her-2/neu754–762)

9 Breast Peptides

HLA-A1 restricted: EADPTGHSY (MAGE-A1161–169); EVDPIGHLY (MAGE-A3 168–176); HLA-A2 restricted: KIFGSLAFL (Her-2/neu 369–377); YLSGADLNL (CEA571–579; asparagine to aspartic acid substitution at position 576); GLYDGMEHL (MAGE-A10 254–262);

HLA-A3 restricted

HLFGYSWYK (CEA27–35); VLRENTSPK (Her-2/neu754–762); SLFRAVITK (MAGE-A1 96–104); and ASGPGGGAPR (NY-ESO-1 53–62)

These peptides include some identified by our group, but most have been identified by other investigators worldwide (1) and were selected based on their proteins of origin and evidence of antigenicity or immunogenicity.

The peptides were vialed either by the Human Immune Therapy Center Immune Monitoring Laboratory (HITC-IML) at the University of Virginia, or under GMP conditions by Clinalfa-Merck. For smaller early phase studies, vialing was done at the University of Virginia: at the time of peptide vialing, the peptides were solubilized in aqueous solutions (without DMSO), sterile-filtered, mixed and then vialed in borosilicate glass vials and stored at −80°C to −20°C protected from light. Vaccines vialed by the HITC-IML were stored as liquid solutions and included the following: 4MP (Lots 11, 14, 18 and 22); Peptide-tet (Lot 20); 12MP (Lot 21); 4 Colon Peptides (Lot 23); 5 Ovarian Peptides (Lot 25); 9 Breast Peptides (Lot 26). The vaccines vialed by Clinalfa (subsequently Merck) were prepared by combining the lyophilized bulk GMP-grade peptides, reconstituting in aqueous solution (without DMSO), then sterile-filtering, vialing, and lyophilizing prior to storage. Vaccines prepared in this manner included the following: Peptide-tet (Lots AC0444 and AC0569); 12MP (Lots AC0441 and AC0558); 6MHP (Lots AC0442, AC0443, AC0626). Stability testing over time was measured and reported on vials taken from the same lot of peptide. Multiple lots of peptides were evaluated for the following vaccines: Peptide-tet, 4MP, 12MP, and 6MHP.

2.2 High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

Peptide solutions were stored at −80°C until use, then a sample containing 3 μg of each peptide was diluted to 200 μL with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) shortly before injection; peptides supplied as powder were dissolved in water. Reverse phase chromatography was performed on a Phenomenex Jupiter C18, (catalog 00F-4053-B0), 2 mm × 150 mm. Solvent A was 0.1% TFA, solvent B was 0.09% TFA in acetonitrile. The column was equilibrated in 5% B (95% A). The elution gradient was 5% B for 5 minutes then 5% to 29% B in 36 minutes then 29% to 70% B in 9 minutes. For early monitoring, the pump was a dual syringe Applied Biosystems 140 (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA), and for later studies an Agilent 1100 pump (Agilent Technologies, Inc.; Santa Clara, CA) whose greater dwell volume made elution times later. Flow rate was 200 μL/minute, column temperature was 40 °C and the effluent was measured by absorbance at 215 nm. Fractions containing peptide were collected manually.

2.3 Mass Spectrometry

The HPLC fractions collected by the Protein Sciences Core were immediately frozen and stored at −20°C in the Mass Spectrometry Core until analysis. When a fraction was to be analyzed, it was thawed and diluted 1:100 in 0.1% TFA. Within 5 minutes, 1μL of the dilution was injected into the mass spectrometer for analysis. The mass spectrometer was one of the following: Thermo Electron LCQ Classic (2000–2002), LCQ DecaXP (2003–2006) or LTQXL (2007-present; Thermo Scientific; Waltham, MA). The sample was injected into the mass spectrometer through a self-packed microcapillary column (75μm × 8cm, Phenomenex C18 -10μm particles) with the tip pulled to ~10μm. The sample was eluted from the column using an acetonitrile gradient in 0.1M acetic acid (0–80% over 20 minutes) at a flow rate of 0.5 μL/min. The instrument was set to acquire 1 MS scan followed by MS/MS scans on the three most abundant ions in the MS scan (repeat count = 2, exclusion duration = 30 sec, threshold = 1E+05). Once acquired, the MS scans were manually examined for non-background ions. Any observed were manually sequenced. For each fraction, the following data were presented for each species detected: SIC (selected ion chromatogram), MS spectrum used to determine the (M+H)+, MS/MS spectrum used to confirm the sequence. For those fractions that contained more than one species, the approximate percentage of each species was calculated using the area under the SICs.

3.0 Results

3.1 Evaluation of multi-peptide vaccines by HPLC and mass spectrometry

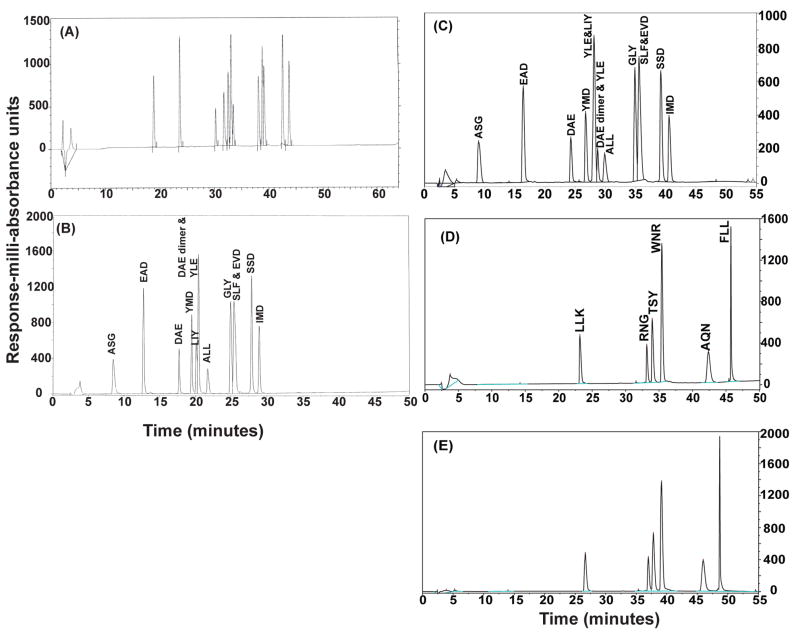

Following synthesis, each peptide used in the vaccine mixtures (Tables 1–3) was evaluated for the presence of a single dominant species by HPLC (data not shown). Following preparation of the peptide mixtures, HPLC was again used to evaluate the purity of each of the mixtures (Figure 1 and data not shown). For the 4-MP vaccine mixture, 4 principal peaks were identified by HPLC, and each of them contained one of the 4 peptides (data not shown). For the 6-MHP vaccine mixture, 6 principal peaks were identified by HPLC (Figure 1D and 1E); again, each represented one of the 6 expected peptides, based on sequence confirmation by mass spectrometry.

Figure 1. Evaluation of multi-peptide preparations by HPLC.

The 12-MP vaccine (Lot 021) was evaluated by HPLC at the time of vialing (A), 7 months post-vialing (B) and again at 5.5 years post-vialing (C). The 6-MHP vaccine (LotAC0442) was evaluated by HPLC 3 years post vialing (D). A second lot of 6-MHP vaccine (Lot AC0626) was evaluated by HPLC 2 years post vialing (E). Differences in the absorbance scale can be due to the amount of peptide that is loaded in the analysis. The total concentration of peptide in each vaccine is confirmed by amino acid analysis at the time of stability testing.

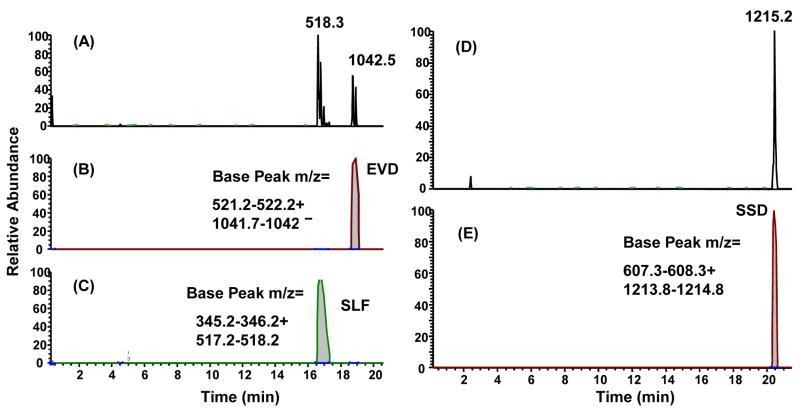

However, for the 12-MP mixture, only 11 of the expected 12 peaks were present using the gradient described in the Materials and Methods (Figures 1A–1C). Mass spectrometric sequencing was performed on each of the HPLC peaks in the 12-MP vaccine to determine whether all 12 peptides were present in the mixture. These analyses demonstrated that fewer than 12 peaks were detected because in some instances two peptide species co-eluted as a single peak. By performing mass spectrometry on the peaks, two peptide species were identified in 2 peaks (Figure 1B) or 3 peaks (Figure 1C). An example of the mass spectrometry profile of peaks containing two peptides is shown in Figure 2A–C, compared to comparable findings with one peptide in a peak (Figure 2D–E). Sequencing of one of the peaks containing two masses revealed the co-elution of peptides MAGE-A1 96–104 (SLFRAVITK, mass 1034) and MAGE-A3 168–176 (EVDPIGHLY, mass 1042) (Figure 2A–C). Also, a dimerized form of the cysteine-containing peptide DAEKSDICTDEY was found (Figure 1B), which co-eluted with the YLEPGPVTA peptide. This is discussed in more detail below. HPLC profiles of different lots of the same peptide mixture were similar, as expected, with slight shifts in elution times due to minor changes in HPLC equipment and gradients (Figure 1).

Figure 2. Mass spectrometry and sequencing of peptides from two peaks derived from the 12-MP vaccine.

Peaks from the HPLC analysis of the 12-MP vaccine were collected and analyzed by mass spectrometry sequencing to confirm that the vaccine specific peptide sequences were present in the mixture. In some instances, multiple masses were detected in a single peak indicating the presence of multiple peptide species (A–C), whereas in the majority of cases single masses and individual peptide species were detected in a given peak (D–E). Panels A and D are total ion chromatograms (TIC) while panels B, C and E are selected ion chromatograms (SIC).

Other peptide mixtures, including the 5 ovarian peptide vaccine, 4 colon peptide vaccine, and 9 breast peptide vaccine, were also separated by HPLC and evaluated by mass spectrometry and sequencing for vaccine specific peptide sequences. These mixtures, containing fairly small numbers of peptides, had stable HPLC profiles over time with no significant changes, confirming the stability of the mixtures (data not shown).

3.2 Individual peptide species within multi-peptide mixtures remain stable over time

The 12-MP vaccine preparation was evaluated by HPLC and mass spectrometry at the time of vialing and at 3–6 month intervals to evaluate the stability of the mixture. The HPLC profiles at the time of vialing, 7 months post-vialing and those run on the same lot of peptide 5.5 years post-vialing were very similar (Figures 1A–C). The HPLC profiles changed slightly over 5 years due to minor changes in HPLC equipment and gradients, but the pattern is retained with only a very minor shift in where the YLE (YLEPGPVTA) peptide elutes. A common degradation product is present both early on and at 5.5 years, and leads to a total of 13 detectable species; this was mentioned above and is discussed further below. That degradation product, a dimer of the cysteine-containing peptide DAEKSDICTDEY (DAE), elutes very close to the YLEPGPVTA (YLE) and LIYRRRLMK (LIY) peptides; so that there is some overlap in both HPLC runs and with very minor variation between them. Regardless, mass spectrometry and sequencing of the peptides in each peak confirmed that the correct peptide sequences were present and no new major species were present, as marked on the graphs (Figure 1B and 1C). Thus the testing of the vaccine through 5.5 years post-vialing supports the conclusion that the peptides within the mixture are stable over extended periods of time. Quantitation of specific degradation products or synthetic contaminants is summarized in Table 4. In a similar way, multiple lots of the 12-MP vaccine preparation and of other peptide vaccine preparations were prepared and evaluated for stability, and met lot release criteria as defined in their respective investigational new drug (IND) applications. The lengths of time that these lots of peptides have remained stable are summarized in Table 5.

Table 4.

Stability of individual peptide species within a 12-peptide mixture

| Peptide Sequence | Protein (aa) number | % in 12-MP (Lot 021) at time of vialing | % in 12-MP (Lot 21) 5.5 years post- vialing |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAEKSDICTDEY | Tyrosinase240–251 | 50 | 78 |

| DAEKSDICTDEY- dimer | 50 | 22 | |

| SSDYVIPIGTY | Tyrosinase146–156 | 100 | 100 |

| EADPTGHSY | MAGE-A1161–169 | 100 | 100 |

| EVDPIGHLY | MAGE-A3168–176 | 100 | 100 |

| YMDGTMSQV | Tyrosinase369–377 | 100 | 100 |

| YM(o)DGTMSQVa | 0 | 0 | |

| IMDQVPFSV | gp100209–217 | 100 | 100 |

| IM(o)DQVPFSV a | gp100209–217 | 0 | 0 |

| YLEPGPVTA | gp100280–288 | 100 | 100 |

| GLYDGMEHL | MAGE-A10254–262 | 100 | 100 |

| ALLAVGATK | gp10017–25 | 100 | 100 |

| ALLAVGAATK | 0 | 0 | |

| LIYRRRLMK | gp100614–622 | 100 | 100 |

| SLFRAVITK | MAGE-A1 96–104 | 100 | 100 |

| ASGPGGGAPR | NY-ESO-153–62 | 99 | 100 |

| ASGPGGGGAPR | 1 | 0 |

M(o) designates oxidation of a methionine residue

Table 5.

Duration of stability of peptide vaccines

| Peptide Mix | Lot # | Stability of peptide vaccines at the time of last evaluation (yrs) |

|---|---|---|

| 4MP | 18 | 5.6+ |

| 22 | 5.5+ | |

| Peptide-tet | 20 | 5.5+ |

| AC0444 | 5.0+ | |

| AC0569 | 2.7+ | |

| 12MP | 21 | 5.5+ |

| AC0441 | 5.0+ | |

| AC0558 | 2.8+ | |

| 6MHP | AC0442 | 5.0+ |

| AC0443 | 5.0+ | |

| AC0626 | 1.7+ | |

| 4 Colon Peptides | 23 | 5.1+ |

| 5 Ovarian Peptides | 25 | 2.8+ |

| 9 Breast Peptides | 26 | 2.5+ |

Lot numbers for peptide mixtures vialed at the University of Virginia and stored in aqueous solution at −80°C are numbers between 18 and 26. Lot numbers beginning with AC were prepared in GMP conditions as lyophilized peptide vials.

Preparations still meeting lot release criteria at the last evaluation are marked with a plus sign.

3.3 Impurities in individual peptide species

Several peptide variants and degradation products have been identified for some of the vaccine mixtures and these variants are listed in Table 4 and described in Table 6. One was the result of a sequencing error at the time of synthesis (ASGPGGGGAPR) and the remaining were the result of post-synthesis changes that may occur under the described conditions.

Table 6.

Peptide variants found in multi-peptide mixtures

| Peptide Variants Following Synthesis | Present under the following conditions | Peptide Sequence | Variant Peptide Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide dimers | Lyophilized and liquid formulations stored at −20°C or −80°C | DAEKSDICTDEY (monomer) | DAEKSDICTDEY (dimer) |

| Addition of amino acid residues | Presumed sequencing error at the time of synthesis | ASGPGGGAPR ALLAVGATK | ASGPGGGGAPR ALLAVGAATK |

| Oxidized methionines | Liquid formulations stored at −20° C or −80°C | IMDQVPFSV | IM(o)DQVPFSV |

| YMDGTMSQV | YM(o)DGTMSQV | ||

| Aspartic Acid-Proline (D-P) popping | Non-GMP lyophilized peptide stored at −20° C | EADPTGHSY | EAD and PTGHSY |

| EVDPIGHLY | EVD and PIGHLY | ||

| Cyclization of unprotected N- terminal glutamate residue to form pyroglutamate | Prevented by adding an alanine residue to the N-terminus to protect the glutamine residue | AQNILLSNAPLGPQFP | pyroglutamate- QNILLSNAPLGPQFP |

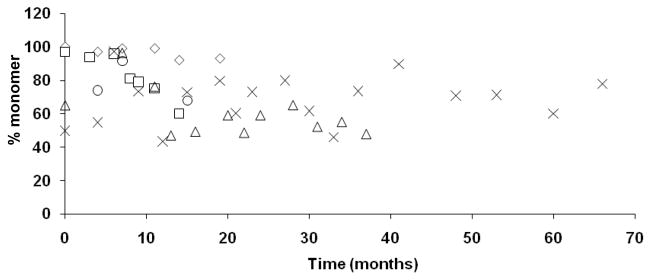

Dimerization of the cysteine containing peptide, DAEKSDICTDEY, has been noted in both liquid and lyophilized peptide preparations stored at −20°C or −80°C although the percentage of dimer formation is greater in preparations stored in liquid at the higher temperature. When solubilized at a high concentration in DMSO instead of water, almost complete dimerization of the peptide occurs regardless of storage temperature (data not shown). Trends in the proportion of dimerized DAEKSDICTDEY peptide vialed in liquid or lyophilized preparations and stored at −80°C are shown in Figure 3. We have consistently seen some degree of dimerization of this cysteine-containing peptide in multiple peptide preparations although overall, roughly one-half of the peptide quantity is preserved as monomer. Despite some unavoidable dimerization of the DAEKSDICTDEY peptide, it is one of the most immunogenic peptides in our vaccine trial experience (6;7;14).

Figure 3. Dimerization of the DAEKSDICTDEY peptide.

Multiple peptide mixtures containing the DAEKSDICTDEY peptide were evaluated over time for the presence of DAEKSDICTDEY dimers by mass spectrometry and sequencing. (◇) 4-MP (Lot 11; liquid preparation); (Δ) 4-MP (Lot 18; liquid preparation); (□) 12-MP (Lot 14; liquid preparation); (X) 12-MP (Lot 21; liquid preparation); (◦) 12-MP (Lot AC0558; lyophilized preparation).

Oxidation of methionine residues has been observed for the methionine-containing peptides YMDGTMSQV and IMDQVPFSV. It represented 3% of the YMDGTMSQV in a liquid formulation stored at −20°C (4 Mel Pep lot 005), and 1–4% of methionine-containing peptides in the 12MP mixture (Lot 021), which was stored at −80°C. We have occasionally observed up to 9% of a methionine-containing peptide to be oxidized in lyophilized form of the individual peptide, but it is usually a very minor contaminant. We have not noted an appreciable increase in the amount of oxidation over time, as determined by comparison of HPLC profiles, suggesting that oxidation most likely occurs during sample handling associated with the analysis procedure (data not shown).

Peptides with an aspartic acid (D) – proline (P) bond are known to be prone to hydrolysis at that bond. This process is sometimes referred to as D-P popping. In non-GMP grade lyophilized peptide preparations of EADPTGHSY (MAGE-A1161–169) and EVDPIGHLY (MAGE-A3 168–176), we observed a dramatic loss of intact peptide when those preparations were stored in a −20°C freezer. A contributing factor may also have been incomplete lyophilization allowing more water to be present. The break in the bond between the aspartic acid and the proline lead to truncated forms of the peptide. In some vialed mixtures, these truncated forms represented from 1–8% of the total peptide. When we have stored lyophilized GMP-grade peptides at −80°C, this degradation process has been avoided. However, it must be remembered when using peptides containing a D-P sequence, avoiding acidic conditions and water can decrease D-P popping, especially at −80°C.

In order to prevent the cyclization of unprotected N-terminal glutamine residues to form pyroglutamate (17), we added an alanine residue to the N-terminus of some peptides that initially had a glutamine residue at the N-terminus. Pyroglutamate formation was not detected in these mixtures. Pyroglutamate formation can also occur with glutamic acid residues at the N-terminus, but our observation is that this occurs less readily than with glutamine (data not shown), and we have not added extra residues to peptides containing glutamic acid at the N-terminus (e.g.: EADPTGHSY and EVDPIGHLY). Pyroglutamate conversion was identified in 0.6% of the EVDPIGHLY peptide as a minor and expected contaminant in the GMP grade peptide, but there was no evidence of increases in that contaminant over time.

4.0 Discussion

Most peptide-based vaccine studies to date have incorporated a single or few peptides in the vaccine regimen. However, most tumors are heterogeneous with respect to expression of tumor-associated antigens; thus, peptide-based vaccines incorporating multiple peptides derived from several different tumor-related antigens may induce a more robust and relevant immune response against tumor, compared to vaccines using only a single antigen. In this report, we provide evidence that it is feasible to combine multiple peptides into a single vaccine mixture and that these mixtures remain stable over many years for use in peptide-based vaccine studies. Importantly, there are molecular approaches for documenting identity and stability of these preparations over time, that have been acceptable to the US Food and Drug Administration, in its oversight of our clinical trials using these peptide vaccines.

Our primary approach for assessing the stability of peptide vaccines involved HPLC and mass spectrometry, both of which have provided evidence that single peptides and peptide mixtures remain stable over time, at least out to 5½ years post-vialing (Tables 4 and 5). An analysis of peptide vaccines by HPLC can assess for the development of new peaks or major shifts in the relative orientation and height of peaks over time, which would suggest the presence of variants of the peptide species (e.g. formation of dimers or the breakdown of the peptide products), or that other contaminants have been introduced into the mixtures. The HPLC profiles of the 12 MP mixture (Figure 1) and other peptide mixtures that we have evaluated over time (data not shown) have been stable with respect to the relative orientation and height of the peptide peaks. Minor shifts in the elution profiles of some of the peptides (Figure 1) are sometimes seen and may be due to slight variations in buffers or columns that are used during the procedure. In this case, mass spectrometry and sequencing of the masses within the dominant peaks is useful for confirming that a mixture contains the known peptides selected for the vaccine, and we have successfully used this approach to confirm the peptide content of our vaccines. Mass spectrometry and sequencing of the masses within dominant peaks has also been useful for the identification of multiple peptides that co-elute within the same peak (Figure 2A).

We have found that lyophilized peptides stored at −80°C appear to be very stable over time. Even storage at −20°C can be adequate, especially for some very stable peptides; however, storage at the lower temperature may further prevent dimerization of cysteine-containing peptides. This is especially true for liquid peptide preparations, whereby storage at −20°C can lead to excessive dimer formation over time, which we have seen in earlier peptide preparations stored in this manner (data not shown). While we consistently see some degree of dimerization of cysteine-containing peptides, approximately 50% or more of the starting material is preserved as monomer when stored at −80°C (Figure 3). Thus, cysteine-containing peptides can be used in vaccine preparations, but caution should be used when storing and handling them to minimize dimerization, which could interfere with biologic activity.

For peptides other than DAEKSDICTDEY, the purity and stability were very high and were comparable in lyophilized and aqueous preparations; however, we suspect that lyophilization minimizes cyclization at N-terminal glutamine residues, cysteine dimerization, and D-P popping, because of the role that hydrolysis can have in D-P popping. Some of the peptides (eg YLEPGPVTA) are very stable even at room temperature, but we have concern that the other more reactive peptides may be less stable in solution, especially at −20°C rather than −80°C.

An important measure of the integrity of single peptide and multi-peptide vaccines is the overall T cell response to the vaccines following immunization. The biologic activity of short peptides is completely predictable based on sequence and mass, and not tertiary structure, with the possible exception of cysteine containing peptides. However, the identification of dimerization is determined by mass spectrometry. Thus, the stability of the native sequence defines the biologically active molecule for these short peptides. The most meaningful result with regards to functionality is that the T cell reactivity rates to the peptides in the multi-peptide vaccine preparations were very comparable among trials conducted over a 10-year time span. Our vaccines have been administered in an emulsion with Montanide ISA-51 adjuvant, and T cell responses to individual and peptide mixtures have been documented in in vitro assays in the majority of patients following vaccination (2;10;14;15). Additionally, responses to multiple peptides restricted to the same HLA molecule and administered as part of the same multi-peptide mixture have been detected (14). Thus, peptide competition for binding to the same HLA molecule is not a limitation for selecting peptides in a vaccine mixture. Combined, from an immunologic standpoint, these data further support the potential for use of multi-peptide vaccines for use in cancer vaccines.

The data presented here demonstrate the stability of individual and multi-peptide vaccine mixtures and can impact the future development of multi-peptide vaccines. The results suggest that peptide vaccines, and in particular multi-peptide vaccines, can be made in bulk and stored for long periods of time without compromising the stability of the peptide mixtures. The production of bulk preparations reduces manufacturing costs and the cost of QA/QC testing of individual lots of peptides. Furthermore, administration of mixtures of peptides as a single vaccine reduces the number of injections required to administer multiple peptides and thus can reduce the number of injection site-related toxicities. While vaccine mixtures have been shown to be stable for long periods of time, we have found it useful to establish the stability of a peptide mixture by evaluating the vaccine every 3–6 months for the first year following manufacture. Based on the data presented here, especially if the peptide vials are stored in lyophilized form at −80°C, subsequent stability testing can safely be repeated yearly.

Table 2.

Four melanoma peptide (4-MP) vaccine: MELITAC 4.0

| Allele | Sequence | Epitope |

|---|---|---|

| HLA-A1 | DAEKSDICTDEY | Tyrosinase 240–251 a |

| HLA-A2 | YMDGTMSQV | Tyrosinase 369–377 b |

| YLEPGPVTA | gp100 280–288 | |

| HLA-A3 | ALLAVGATK | gp100 17–25 |

(substitution of S for C at residue 244)

(post-translational change of N to D at residue 371)

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by NIH grants to CLS (R01 CA57653, R01 CA104362, R01 CA118386, R21 CA105777, R21 CA103528, R01 CA78519), support from the Cancer Research Institute for a peptide vaccine for ovarian cancer, philanthropy from the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research, and support from the UVA Cancer Center (pilot funds) and the UVA Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA44579) for use of the Biomolecular Research Facility and pilot funds.

The authors would like to thank Elizabeth M.H. Woodson and Scott A. Boerner for their assistance with the submission of vaccine materials for Quality Assurance/Quality Control testing. The authors would also like to thank the members of the University of Virginia Biomolecular Research Facility and Donna Deacon for their assistance with the synthesis and preparation of vaccine materials, and for HPLC and mass spectrometric analyses. The Biomolecular Research Facility is part of the University of Virginia Cancer Center. The authors would like to thank the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research, Alice T. and William H. Goodwin, Jr., Rebecca T. and James P. Craig, III, Richard and Sherry Sharp, and George S. and Linda L. Suddock for their financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Novellino L, Castelli C, Parmiani G. A listing of human tumor antigens recognized by T cells: March 2004 update. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54(3):187–207. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0560-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slingluff CL, Jr, Chianese-Bullock KA, Bullock TN, Grosh WW, Mullins DW, Nichols L, et al. Immunity to melanoma antigens: from self-tolerance to immunotherapy. Adv Immunol. 2006;90:243–295. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thurner B, Haendle I, Roder C, Dieckmann D, Keikavoussi P, Jonuleit H, et al. Vaccination with mage-3A1 peptide-pulsed mature, monocyte-derived dendritic cells expands specific cytotoxic T cells and induces regression of some metastases in advanced stage IV melanoma. J Exp Med. 1999;190(11):1669–1678. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nestle FO, Alijagic S, Gilliet M, Sun Y, Grabbe S, Dummer R, et al. Vaccination of melanoma patients with peptide- or tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1998;4(3):328–332. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Schwartzentruber DJ, Hwu P, Marincola FM, Topalian Sl, et al. Immunologic and therapeutic evaluation of a synthetic peptide vaccine for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat Med. 1998;4(3):321–327. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slingluff CL, Jr, Petroni GR, Yamshchikov GV, Barnd DL, Eastham S, Galavotti H, et al. Clinical and immunologic results of a randomized phase II trial of vaccination using four melanoma peptides either administered in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in adjuvant or pulsed on dendritic cells. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(21):4016–4026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slingluff CL, Jr, Petroni GR, Yamshchikov GV, Hibbitts S, Grosh WW, Chianese-Bullock KA, et al. Immunologic and clinical outcomes of vaccination with a multiepitope melanoma peptide vaccine plus low-dose interleukin-2 administered either concurrently or on a delayed schedule. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(22):4474–4485. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamshchikov GV, Barnd DL, Eastman S, Galavotti HS, Patterson JW, Deacon DH, et al. Evaluation of peptide vaccine immunogenicity in draining lymph nodes and peripheral blood of melanoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:703–711. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010601)92:5<703::aid-ijc1250>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knutson KL, Schiffman K, Disis Ml. Immunization with a HER-2/neu helper peptide vaccine generates HER-2/neu CD8 T-cell immunity in cancer patients. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(4):477–484. doi: 10.1172/JCI11752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chianese-Bullock KA, Irvin WP, Jr, Petroni GR, Murphy C, Smolkin M, Olson WC, et al. A multipeptide vaccine is safe and elicits T-cell responses in participants with advanced stage ovarian cancer. J Immunother. 2008;31(4):420–430. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31816dad10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Disis Ml, Grabstein KH, Sleath PR, Cheever MA. Generation of immunity to the HER-2/neu oncogenic protein in patients with breast and ovarian cancer using a peptide-based vaccine. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(6):1289–1297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valmori D, Dutoit V, Ayyoub M, Rimoldi D, Guillaume P, Lienard D, et al. Simultaneous CD8+ T cell responses to multiple tumor antigen epitopes in a multipeptide melanoma vaccine. Cancer Immun. 2003;3:15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberg SA, Sherry RM, Morton KE, Scharfman WJ, Yang JC, Topalian Sl, et al. Tumor progression can occur despite the induction of very high levels of self/tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in patients with melanoma. J Immunol. 2005;175(9):6169–6176. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slingluff CL, Jr, Petroni GR, Chianese-Bullock KA, Smolkin ME, Hibbitts S, Murphy C, et al. Immunologic and Clinical Outcomes of a Randomized Phase II Trial of Two Multipeptide Vaccines for Melanoma in the Adjuvant Setting. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(21):6386–6395. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slingluff CL, Petroni GR, Olson WC, Czarkowski AR, Grosh WW, Smolkin ME, et al. Helper T cell responses and clinical activity of a melanoma vaccine with multiple peptides from MAGE and melanocytic differentiation antigens. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(30):4973–4980. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slingluff CLJ, Yamshchikov G, Neese P, Galavotti H, Eastham S, Engelhard VH, et al. Phase I trial of a melanoma vaccine with gp100(280–288) peptide and tetanus helper peptide in adjuvant: immunologic and clinical outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(10):3012–3024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson LW, Hogan KT, Caldwell JA, Pierce RA, Hendrickson RC, Deacon DH, et al. Preventing the spontaneous modification of an HLA-A2-restricted peptide at an N-terminal glutamine or an internal cysteine residue enhances peptide antigenicity. J Immunother. 2004;27(3):177–183. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200405000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]