Abstract

The transcription factor Ets-variant gene 5 (ETV5) is essential for spermatogonial stem cell (SSC) self-renewal, as targeted deletion of the Etv5 gene in mice (Etv5−/−) results in only the first wave of spermatogenesis. Reciprocal transplants of neonatal germ cells from wild type and Etv5−/− testes were performed to determine the role of ETV5 in Sertoli cells and germ cells. ETV5 appears to be needed in both cell types for normal spermatogenesis. In addition, Etv5−/− recipients displayed increased interstitial inflammation and tubular involution after transplantation. Preliminary studies suggest that the blood-testis-barrier (Sertoli-Sertoli tight junctional complex) is abnormal in the Etv5−/− mouse.

Keywords: Ets-Related Molecule, ERM, Spermatogonial Stem Cell, Sertoli Cell, Germ Cell Transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Ets-variant gene 5 (ETV5; also known as Ets-related molecule or ERM), is a member of the PEA3 subfamily of ETS family of transcription factors.1 ETS family members mediate hematopoesis, angiogenesis, neuronal growth, cell cycle regulation, and metastatic ability of tumor cells.1, 2 ETV5 has a specific role in the maintenance and self-renewal of spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs), the stem cell pool of the male germ line. Mice with a targeted deletion of Etv5 (Etv5−/−) undergo the first wave of spermatogenesis, but during this time their SSCs disappear,3 probably through differentiation and lack of proliferation.4, 5 There is progressive loss of germ cell layers starting with spermatogonia and progressing through spermatocytes and finally the round and elongate spermatids.5 This results in adult Etv5−/− mice with a Sertoli cell-only phenotype.

Testicular ETV5 expression has been previously localized to adult Sertoli cells, the supporting somatic cells of the seminiferous epithelium.5 Further investigations have since revealed that the neonatal testis also expresses this transcription factor in both germ cells and Sertoli cells.4 Neonatal expression of ETV5 in both these cell compartments raises many questions regarding its potential function in SSC self-renewal and its specific roles in Sertoli and germ cells. Like all stem cell pools, SSCs maintain a balance between self-renewal and differentiation.6 This regulation is dependent upon factors produced in both supporting somatic cells and the stem cells and subsequent intercellular communication between these cell types in the microenvironment termed the spermatogonial stem cell niche.6

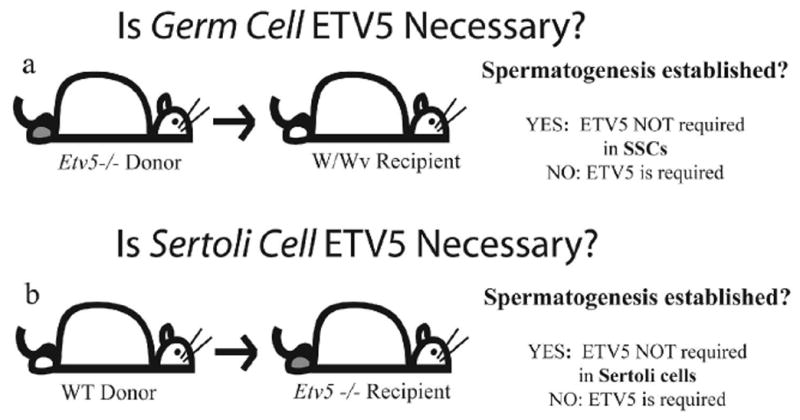

The relative importance of ETV5 in neonatal Sertoli and germ cells to maintenance of the SSC niche can be evaluated by reciprocal SSC transplants between wild type (WT) and Etv5−/−hosts and donors. SSC transplants were first described by Brinster and colleagues.7, 8 This technique has since been used by numerous investigators to evaluate various germ cell populations that have been manipulated in vitro or derived from gene-modified mice for “stemness”. SSC transplants can also evaluate the ability of Sertoli cells in genetically modified mice to support spermatogenesis. Thus the role of neonatal germ cell ETV5 can be studied by transplanting germ cells from Etv5−/− testes into germ cell-depleted recipient testes with normal Sertoli cells. Transplantation of wild type (WT) germ cells into Etv5−/− testes evaluates the role of Sertoli cell ETV5 in supporting spermatogenesis. The absence or presence of spermatogenesis indicates that ETV5 is or is not needed, respectively, in the cell type being investigated (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Transplants from Etv5−/− donor mice into germ cell depleted WT testes evaluate the role of ETV5 in germ cells (a), while transplants of WT germ cells into Etv5−/− testes evaluates the role of ETV5 in Sertoli cells (b).

Data from these reciprocal transplants suggest that ETV5 may have roles in both germ cells and Sertoli cells for the support of spermatogenesis. In addition, an unexpected discovery from these experiments suggests that the blood-testes barrier is abnormal in Etv5−/− mice and that these mice may have altered testicular immune privilege.

ETV5 AND SPERMATOGENESIS

Germ cells from neonatal Etv5−/− donor testes were transplanted into W/W−v mouse recipients. These mice are ideal transplant recipients because mutations on each of the c-kit alleles block germ cell differentiation, resulting in a testis without spermatogenesis.9 However, the Sertoli cells are normal and support spermatogenesis of transplanted germ cells.9 No spermatogenesis was observed in preliminary experiments with germ cells from Etv5−/− mice, despite the fact that WT germ cells re-established spermatogenesis in the W/W−v hosts. An elaboration of the repeat of this experiment will be presented in a forthcoming paper.4

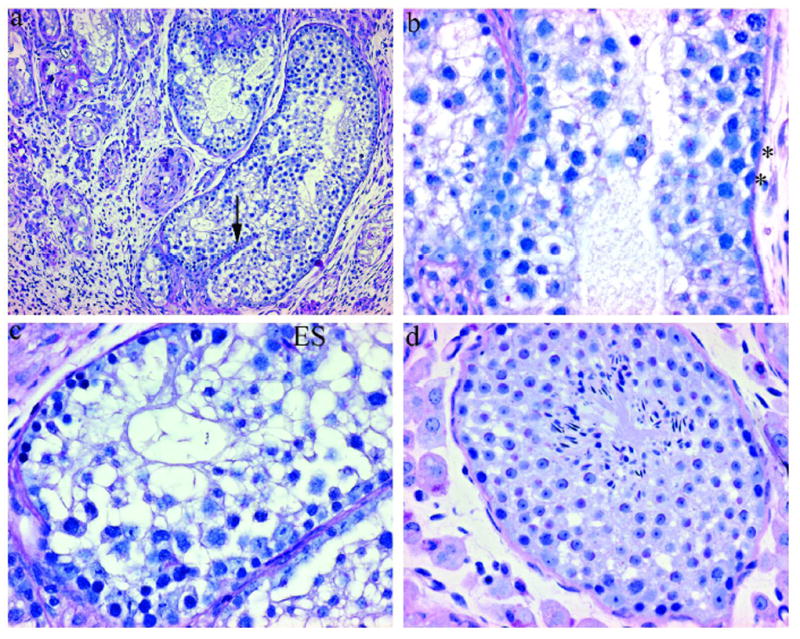

In the reciprocal transplant, WT germ cells were injected into adult Etv5−/− testes (in which Sertoli cells were lacking ETV5 and germ cells are absent). Data suggest that ETV5 is also required in the Sertoli cells, as spermatogenesis was not established, except in one testis and only within one seminiferous tubule, compared to multiple tubules in control (WT cells into W/W−v) mice. Furthermore, spermatogenesis appeared qualitatively deficient in the Etv5−/− tubule, with abnormal growth of the basement membrane, epithelial disorga2nization, and mixing of germ cells within stages (Figure 2). Occasional spermatogonia were seen, along with spermatocytes, round spermatids, as well as rare misaligned elongate spermatid heads.

Figure 2.

Testes from an Etv5−/− recipient that received neonatal WT germ cells (a, b, c) and an age-matched untransplanted control. (PAS/hematoxylin) a) Seminiferous tubule with spermatogenesis and bisecting basement membrane (arrow). (100x) b and c) Spermatogenesis is disorganized but contains all germ cell types, including spermatogonia (*) and elongate spermatids. (400x) (ES). d) Endogenous spermatogenesis, with no spermatogonia, is occasionally seen in older Etv5−/− mice. The germ cells lining the basement membrane are pre-leptotene spermatocytes. (400x)

Several potential explanations for this limited spermatogenesis in a single Etv5−/− host have been considered. First, it is possible that rare WT SSCs managed to establish themselves, but due to lack of ETV5-induced Sertoli cell signals, they did not undergo normal, stage-synchronized spermatogenesis. Second, WT Sertoli cells are found in the transplant cell suspension, along with WT SSCs. These transplanted Sertoli cells may have persisted and established limited spermatogenesis in the Etv5−/− seminiferous tubule in association with the WT SSCs. Sertoli cells from perinatal mice have been shown to colonize the seminiferous tubules of Steel/Steeldickie (Sl/Sld) and busulfan-treated WT mice.10, 11 Sl/Sld mouse Sertoli cells cannot support spermatogenesis due to mutations in the gene encoding the Kit ligand and thus cannot properly signal spermatogonia to differentiate; therefore any areas of spermatogenesis seen in Sl/Sld recipients would be due to transplanted Sertoli cells.12 Interestingly, oddly shaped structures with basement membranes located in the interior of larger tubules, similar to what was seen in the Etv5−/− recipient, were noted in those recipients.10, 11 These “minitubules” had varied spermatogenesis, including spermatogonia as the only germ cell type, disorganized spermatogenesis, and full, stage synchronized spermatogenesis.10, 11 Third, limited spermatogenesis in the Etv5−/− recipient testes may represent endogenous spermatogenesis that was disrupted by transplant-associated inflammation. Residual spermatogenesis is occasionally seen in adult Etv5−/− mice and probably represents the final phases of the first wave. However, residual spermatogenesis that has been observed in Etv5−/− adults only appears in short tubule segments, generally < 60 μm of sectioned testes and spermatogonia are absent in those tubules (Figure 2d). In contrast, the one tubule with spermatogenesis in the Etv5−/− recipient was relatively long and contained spermatogonia. Current experiments using germ cells from green fluorescent mice transplanted into Etv5−/− hosts will help to differentiate among these 3 possible explanations.

ETV5, THE BLOOD-TESTES BARRIER, AND TESTICULAR IMMUNITY

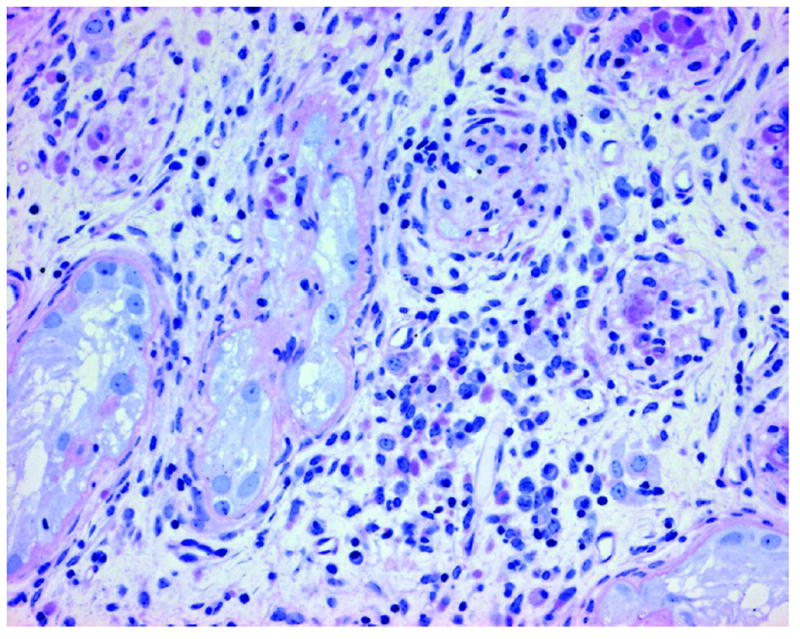

An unexpected but interesting observation was noted in all Etv5−/− recipient testes that received WT germ cells. All of these testes displayed severe and diffuse interstitial inflammation and fibrosis (Figure 3). Interstitial cellularity was greatly increased and consisted of a mixture of fibroblasts, macrophages, and plasma cells. Most of the seminiferous tubule cross sections in these testes were at various stages of involution. Thickened basement membranes and occasional inflammatory cell infiltration were seen in partially involuted tubules, while the presence of other tubules could only be identified by a swirl of connective tissue.

Figure 3.

Etv5−/− recipient testes have a severe interstitial reaction, including increased interstitial cellularity and seminiferous tubule involution. (PAS/hematoxylin; 200x)

In other germ cell transplant studies, fibrosis due to presumptive inflammation among some recipient testes has been noted.13 Also, increases in intratubular macrophage number and activity have been documented at various time points 24 hours through 3 months post-transplantation.14, 15 The transplant process can be traumatic for recipient testes, as evidenced by 1/3-1/2 of recipient testes with extratubular germ cells at time points < 24 hours post-transplant.14 The presence of these extratubular germ cells, along with trauma that occurs to the seminiferous tubules or rete testes, are the presumed inducers of inflammation.14 This is consistent with what was seen in the control testes of this experiment, in which some testes had mild, focal interstitial inflammation in the rete testes area.

It is unknown whether this widespread inflammation in the Etv5−/− recipient mice is due to intrinsic factors or extrinsic factors related to the transplant procedure. Intrinsic factors would include loss of ETV5 or mouse strain effects upon the physical integrity of the blood-testes barrier, the immune response to normal transplant trauma, and age of the mice. Extrinsic factors would include immuno-compatibility of the donor cells and operator experience in transplant techniques. These extrinsic factors are considered less likely causes. The donor mice were from the same colony and thus presented the same immunological background as the recipients. Excess trauma induced by the transplantation seems unlikely, as evidenced by the lack of widespread inflammation among the control recipient testes. The intrinsic factor of mouse age is also unlikely, as age-matched Etv5−/− testes that did not receive cells were not inflamed.

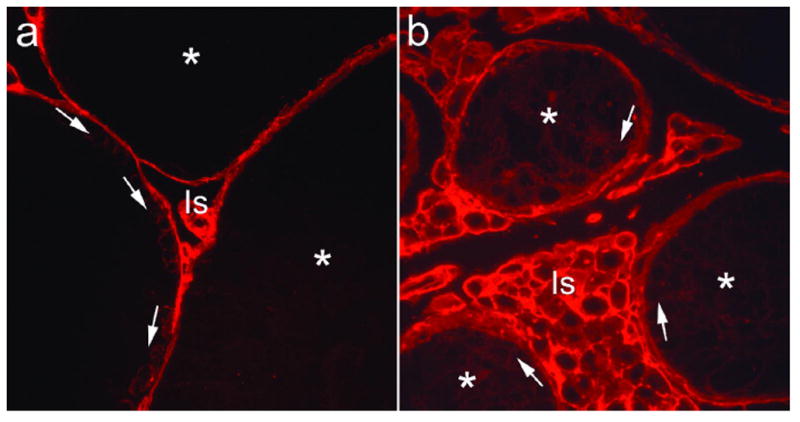

Initial investigations suggest that the blood-testes barrier (Sertoli-Sertoli junction) in Etv5−/− mice is abnormal. A biotin tracer was injected into the interstitial space of the testes prior to euthanasia and visualized with strepavidin-conjugated fluorescent dye.16 The presence of intratubular fluorescence in Etv5−/− testes indicates that tracer leakage does occur beyond the normal barrier along the basement membrane region (Figure 4). Whether ETV5 regulation of the blood-testes barrier is direct or indirect is unknown at this time. Expression of chemokines (CXCL-12/SDF-1; CXCL-5/LIX; CCL-7/MCP-3), mRNA stability regulators (ELAV-like 2/Hu antigen B), protein stability regulators (ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1), and matrix remodeling proteins (matrix metalloproteinase 12) are decreased in Etv5−/− Sertoli cells.5 While the role of these specific proteins upon the blood-testes barrier have not been investigated to date, related proteins and family members of those listed have been shown to be critical in modulating various components that contribute to blood-testes barrier function.17

Figure 4.

Comparison of blood-testes barrier integrity in WT (a) and Etv5−/− (b) mice. The biotin tracer was seen throughout the interstitial space (Is) in WT and Etv5−/− mice. Within WT seminiferous tubules, tracer surrounded germ cells that lie below the Sertoli-Sertoli cell barrier, including spermatogonia and preleptotene spermatocytes (arrows), but the adluminal space and lumen contained no tracer (*). In Etv5−/− tubules, tracer was observed throughout the adluminal and luminal space (*), as well as beneath the normal region for the barrier (arrows). (400x)

ETV5 may also mediate the immune response to transplant trauma, as interleukin-6 (IL-6) is decreased in Etv5−/− Sertoli cells.5 Among its many physiologic roles, IL-6 can act as an inflammatory or anti-inflammatory cytokine, depending upon local tissue environment and balance of intracellular signaling cascade molecules.18 It appears to have varying roles in models of rodent experimental autoimmune orchititis. In a mouse model, exogenously administered IL-6 decreased both the incidence and severity of orchitits.19 However, the patterns of IL-6 and IL-6 receptor expression, along with germ cell apoptosis counts and measurement of IL-6 in testicular macrophage conditioned media, revealed that endogenous IL-6 produced by newly recruited testicular macrophages mediated the inflammatory response in a rat model.20 What role decreased Sertoli cell IL-6 would have on the inflammatory response seen in transplanted Etv5−/−mice is presently unknown.

SUMMARY

Current data suggest that ETV5 expression in neonatal germ cells is needed for the establishment of the spermatogonial stem cell pool and its subsequent self-renewal and maintenance. Sertoli cell ETV5 also appears to be needed for normal spermatogenesis. These initial experiments also suggest that Sertoli cell ETV5 has additional functions in maintaining the blood-testes barrier integrity and mediating normal testicular immune response. Experiments to clarify and expand upon these observations are currently ongoing.

References

- 1.de Launoit Y, et al. The Ets transcription factors of the PEA3 group: Transcriptional regulators in metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oikawa T, Yamada T. Molecular biology of the Ets family of transcription factors. Gene. 2003;303:11–34. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlesser HN, et al. Effects of Ets variant gene 5 (ERM) on testis and body growth, time course of spermatotonial stem cell loss, and fertility in mice. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.062935. In Submission. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyagi G, et al. Ets Variant Gene 5 (ERM) is expressed in testicular germ cells, and its effects on stem cell self-renewal may be mediated through RET In Submission. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C, et al. ERM is required for transcriptional control of the spermatogonial stem cell niche. Nature. 2005;436:1030–4. doi: 10.1038/nature03894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hess RA, et al. Mechanistic Insights into the Regulation of the Spermatogonial Stem Cell Niche. Cell Cycle. 2006:5. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.11.2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinster RL, Avarbock MR. Germline transmission of donor haplotype following spermatogonial transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11303–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brinster RL, Zimmermann JW. Spermatogenesis following male germ-cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11298–302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohta H, Tohda A, Nishimune Y. Proliferation and differentiation of spermatogonial stem cells in the w/wv mutant mouse testis. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1815–21. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.019323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinohara T, et al. Restoration of spermatogenesis in infertile mice by Sertoli cell transplantation. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:1064–71. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.009977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, et al. Germline niche transplantation restores fertility in infertile mice. Hum Reprod. 2005 doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flanagan JG, Chan DC, Leder P. Transmembrane form of the kit ligand growth factor is determined by alternative splicing and is missing in the Sld mutant. Cell. 1991;64:1025–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90326-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shinohara T, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Functional analysis of spermatogonial stem cells in Steel and cryptorchid infertile mouse models. Dev Biol. 2000;220:401–11. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parreira GG, et al. Development of germ cell transplants in mice. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:1360–70. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.6.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parreira GG, et al. Development of germ cell transplants: morphometric and ultrastructural studies. Tissue Cell. 1999;31:242–54. doi: 10.1054/tice.1999.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng J, et al. Androgens regulate the permeability of the blood-testis barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16696–700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506084102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lui WY, Cheng CY. Regulation of cell junction dynamics by cytokines in the testis-A molecular and biochemical perspective. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamimura D, Ishihara K, Hirano T. IL-6 signal transduction and its physiological roles: the signal orchestration model. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;149:1–38. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, et al. Prevention of murine experimental autoimmune orchitis by recombinant human interleukin-6. Clin Immunol. 2002;102:135–7. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rival C, et al. Interleukin-6 and IL-6 receptor cell expression in testis of rats with autoimmune orchitis. J Reprod Immunol. 2006;70:43–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]