Abstract

Aims

To present the prevalence and correlates of hallucinogen use disorders (HUDs: abuse or dependence) and subthreshold dependence.

Methods

The study sample included adolescents aged 12–17 years (N = 55,286) who participated in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2004–2006). Data were collected with a combination of computer-assisted personal interviewing and audio computer-assisted self-interviewing.

Results

The overall prevalence of HUDs among adolescents was low (<1%). However, more than one in three (38.5%) MDMA users and nearly one in four (24.1%) users of other hallucinogens reported HUD symptoms. MDMA users were more likely than users of other hallucinogens to meet criteria for hallucinogen dependence: 11% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 8.24–14.81) vs. 3.5% (95% CI: 2.22–5.43). Compared with hallucinogen use only, subthreshold dependence was associated with being female (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.8 [95% CI: 1.08–2.89]), ages 12–13 years (AOR = 3.4 [1.64–7.09]), use of hallucinogens ≥52 days (AOR = 2.4 [1.66–6.92]), and alcohol use disorder (AOR = 1.8 [1.21–2.77]). Compared with subthreshold dependence, abuse was associated with mental health service use (AOR = 1.7 [1.00–3.00]) and opioid use disorder (AOR = 4.9 [1.99–12.12]); dependence was associated with MDMA use (AOR = 2.2 [1.05–4.77]), mental health service use (AOR = 2.9 [1.34–6.06]), and opioid use disorder (AOR = 2.6 [1.01–6.90]). MDMA users had a higher prevalence of most other substance use disorders than users of non-hallucinogen drugs.

Conclusions

Adolescent MDMA users appear to be particularly at risk for exhibiting hallucinogen dependence and other substance use disorders.

Keywords: Alcohol use disorder, Ecstasy, MDMA, Hallucinogen use disorder, Marijuana use disorder, Subthreshold dependence

1. Introduction

Little is known about hallucinogen use disorders (HUDs) in general and among adolescents in particular (Wu et al., 2008a). The category of hallucinogens consists of several drugs, including lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), phencyclidine (PCP), peyote, mescaline, psilocybin mushrooms, and MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine or ecstasy) (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA], 2007; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2007a). Of all hallucinogens, MDMA is perhaps the most controversial and health-compromising due to its robust association with polysubstance use and potential neurotoxic effects on the human brain (e.g., Gouzoulis-Mayfrank and Daumann, 2006; Reneman et al., 2006).

Although MDMA is classified as an hallucinogen by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000) and U.S. national surveys (NIAAA, 2007; SAMHSA, 2007a), MDMA is distinct from other hallucinogens in regards to its pharmacological effects both as a stimulant and a psychedelic. The use of MDMA induces the rapid and powerful release of serotonin and, to a lesser extent, dopamine from presynaptic terminals (Gouzoulis-Mayfrank and Daumann, 2006). MDMA has been found to cause long-lasting damage to serotonin-containing neurons in animals (Gouzoulis-Mayfrank and Daumann, 2006). Neuroimaging findings from human subjects indicate that repeated MDMA use may increase the risk of developing subcortical, and possibly cortical, reductions in serotonin transporter densities, a marker of serotonin neurotoxicity (Reneman et al., 2006). MDMA use is also significantly associated with impulsiveness, memory deficits, and mood disturbances (Montoya et al., 2002; Parrott, 2001). The many reports on residual neuropsychiatric effects of MDMA in humans are alarming, even though the extent and nature of MDMA-induced serotonin neurotoxicity remains uncertain (Gudelsky and Yamamoto, 2008; Gouzoulis-Mayfrank and Daumann, 2006).

MDMA use also increases healthcare use and can be fatal. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, MDMA-related mortality and morbidity rose substantially (Cregg and Tracey, 1993; Patel et al., 2004; Schifano et al., 2003; SAMHSA, 2002). Similarly, results from Monitoring the Future (MTF) surveys of adolescent students have indicated that, since 2000–2001, lifetime MDMA use (e.g., 4.3–5.2% among 8th graders) has exceeded lifetime LSD use (e.g., 3.4–3.9% among 8th graders) (Johnston et al., 2008). LSD use among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders has declined since 1996, with a particularly sharp decline between 2001 and 2003, which was accompanied by a rise in MDMA use. Beginning in 2001, the prevalence of lifetime MDMA use has remained higher than the prevalence of lifetime LSD use among adolescent students (Johnston et al., 2008). National surveys of both students and the general population also showed a decline in MDMA use in 2003; however, use of this drug appeared to resurge between 2006 and 2007 and remained stable in 2008 (Johnston et al., 2007a, 2008; SAMHSA, 2007a). The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) reports that, in 2006, 77% of the 1.1 million new past-years users of hallucinogens had used MDMA (SAMHSA, 2007a). The NSDUH reveals further that the number of new past-year MDMA users increased substantially from approximately 642,000 in 2003 to 860,000 in 2006 (SAMHSA, 2007a) and that females were significantly more likely than males to be new MDMA users (SAMHSA, 2007b). The 2006 and 2007 MTF surveys of adolescent students reported that MDMA was the only illicit drug that demonstrated evidence of an increase in use and a concomitant decline in perceptions of associated risks (Johnston et al., 2007a, 2007b).

Further, epidemiological studies indicate that young hallucinogen users in general, and MDMA users in particular, are at risk for using cigarettes, alcohol, and other drugs (Pedersen and Skrondal, 1999; Rickert et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2006; Yacoubian, 2003). Reports have suggested that marijuana and opioids are used by MDMA users to relieve the discomfort associated with post-MDMA episodes and that cocaine is used to intensify the MDMA experience (Parrott, 2001, 2006). The use of polysubstances among adolescents is of particular concern because MDMA and other substances are likely to have profound and long-term adverse effects on adolescents’ developing brains and health (Montoya et al., 2002; National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2008a).

Despite the increasing rate of MDMA use and its association with morbidity and mortality, there are few available epidemiological data on HUDs (dependence on and abuse of hallucinogens) and subthreshold dependence (“diagnostic orphans,” see below) among adolescents. According to the DSM-IV, drug dependence is characterized as a pattern of neuroadaptation, maladaptive cognitions, and impaired control related to drug use, and the diagnosis requires the presence of at least three criteria of dependence (APA, 2000). Abuse, on the other hand, is defined only in reference to the harmful consequences of repeated drug use, and the diagnosis requires only one positive criterion (APA, 2000). Hence, drug users characterized by subthreshold dependence, who exhibit only one or two dependence criteria and no abuse criteria and whose drug use behaviors may place them at risk for adverse consequences, may be overlooked by researchers and clinicians. This group has been termed diagnostic orphans (Hasin and Paykin, 1998, 1999).

The limited pertinent studies on alcohol (Eng et al., 2003; Sarr et al., 2000), marijuana (Degenhardt et al., 2002), and opioids (Wu et al., 2008b) suggest that diagnostic orphans or individuals with subthreshold dependence often manifest patterns of substance use behaviors that resemble those meeting criteria for abuse. The only study of the prevalence and correlates of HUDs and subthreshold dependence in a large representative sample of adults aged 18 years or older demonstrates that subthreshold hallucinogen dependence is about three times as prevalent as dependence and twice as common as abuse (Wu et al., 2008a). As is the case with dependence, subthreshold hallucinogen dependence is associated with major depressive episodes (Wu et al., 2008a). Understanding the extent and correlates of subthreshold dependence and HUDs among adolescents is particularly important because drug use is likely to have a profound adverse impact on this young population (NIDA, 2008a), and subthreshold dependence may serve as an early sign of more problematic drug use patterns that require tailored interventions.

There is also reason for concern that even though the substance use behaviors of subthreshold-dependent users may place them at risk for substance use-related problems and harm, they are not captured by the DSM-IV and hence may be missed by clinicians or researchers (Degenhardt et al., 2002; Sarr et al., 2000). Because a diagnosis is often used as a criterion for estimating treatment needs, selecting participants for clinical research, and determining appropriate treatment modalities (Carroll, 1997; Wang et al., 2005), it is important to assess not only HUDs but also subthreshold dependence. It is also important to understand the degree to which subthreshold-dependent users’ substance use-related problems and mental health problems resemble those of diagnostic groups that meet clinical thresholds (e.g., Hasin and Paykin, 1998, 1999; Wu et al., 2008a, 2008b). The available limited data suggest that MDMA users may be at greater risk for experiencing symptoms of hallucinogen dependence than are users of other hallucinogens (Cottler et al., 2001; Stone et al., 2006).

In light of the dearth of national data on hallucinogen-related disorders, we investigate the prevalence and correlates of hallucinogen dependence, abuse, and subthreshold dependence in a large nationally representative sample of adolescents. Given the increasing rate of MDMA use, its distinct pharmacological effects as a hallucinogenic stimulant, and its association with polysubstance use, we investigate further whether MDMA use as compared with use of other hallucinogens is associated with greater odds of HUDs and subthreshold dependence that is independent of the influence of other substance use disorders and patterns of hallucinogen use. Study results from this investigation are likely to have implications for prevention efforts and research, including providing useful data on subthreshold dependence for the next DSM (Saunders, 2006). We address three main questions:

What is the prevalence of past-year hallucinogen dependence, abuse, and subthreshold dependence among hallucinogen users?

Are MDMA users more likely than other hallucinogen users to meet criteria for dependence, abuse, and subthreshold dependence?

Are these three diagnostic categories differentially associated with substance use disorders (tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and opioids), mental health, criminal behavior, and users’ key demographic characteristics?

2. Methods

2.1. Data source

The NSDUH is the largest ongoing survey of substance use and related disorders in the United States, employing multistage area probability sampling methods to select a representative sample of the nation’s civilian, non-institutionalized population aged 12 years and older (SAMHSA, 2007a). The survey covers approximately 98% of the U.S. population, including household residents; residents of shelters, rooming houses, college dormitories, migratory workers’ camps, and halfway houses; and civilians living on military bases. Individuals with no fixed household address (e.g., homeless persons), active-duty military personnel, and residents of institutional group quarters (e.g., correctional facilities and long-term hospitals) are excluded from the survey’s sampling frame.

Participants were interviewed in private at their places of residence. Confidentiality was stressed in all written and oral communications with potential respondents. Data were collected with a combination of computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) and audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) to increase the validity of respondents’ reports of drug use behaviors (Turner et al., 1998). Initial items related to their demographic characteristics were administered by a field interviewer via CAPI. The interview then transitioned to ACASI, which provided respondents with a private, confidential setting in which to answer sensitive questions (e.g., substance use behaviors). Questions were displayed on a computer screen and read through headphones to respondents, who entered answers directly into the computer.

From 2004–2006, approximately 68,000 unique respondents completed the annual survey (SAMHSA, 2005, 2006, 2007a). Weighted response rates for completed interviews among adolescents aged 12–17 years were generally high (85%–88%). The study sample of each annual, independent survey is considered representative of the U.S. general population aged 12 years and older. NSDUH data collection procedures are reported in detail elsewhere (SAMHSA, 2007a).

2.2. Study sample

We focused on adolescents aged 12–17 years from the public-use data files of the 2004–2006 NSDUH. We combined three years of the survey to increase statistical power (N = 55,286). There was little yearly variation in the distribution of respondents’ demographic characteristics. In this combined sample (N = 55,286), 49% of participants were female and 39% were members of nonwhite racial groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected demographic characteristics of past-year hallucinogen users among adolescents aged 12–17 years (N = 55,286)

| Adjusted logistic regression analysis1 | Sample size | MDMA use vs. no use2 | Other hallucinogen use vs. no use2 | MDMA use vs. other hallucinogen use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample characteristics | 100% | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 51.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Female | 48.9 | 1.4 (1.13–1.70) | 0.8 (0.71–0.99) | 1.7 (1.31–2.08) |

|

| ||||

| Age group in years | ||||

| 12–13 | 32.5 | 0.1 (0.05–0.11) | 0.2 (0.13–0.22) | 0.5 (0.27–0.73 |

| 14–15 | 34.4 | 0.4 (0.28–0.45) | 0.5 (0.38–0.55) | 0.8 (0.58–1.03) |

| 16–17 | 33.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 60.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| African American | 15.2 | 0.4 (0.25–0.51) | 0.2 (0.14–0.32) | 1.7 (0.95–2.90) |

| American Indian/Alaska native | 0.6 | 0.5 (0.27–1.09) | 2.6 (1.53–4.43) | 0.2 (0.08–0.51) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander/native Hawaiian | 4.4 | 0.3 (0.13–0.88) | 0.1 (0.04–0.29) | 3.0 (0.76–11.75) |

| Multi-racial | 1.6 | 1.2 (0.67–2.27) | 1.2 (0.68–2.20) | 1.0 (0.40–2.53) |

| Hispanic | 17.4 | 0.7 (0.47–0.92) | 0.7 (0.48–0.93) | 1.0 (0.610–1.56) |

|

| ||||

| Student status | ||||

| Yes | 98.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| No | 1.5 | 3.5 (2.23–5.64) | 1.5 (1.00–2.18) | 2.4 (1.37–4.17) |

|

| ||||

| Family income | ||||

| $0–$19,999 | 17.7 | 1.0 (0.69–1.52) | 1.3 (0.98–1.77) | 0.8 (0.48–1.27) |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 22.3 | 1.1 (0.78–1.41) | 1.0 (0.75–1.33) | 1.1 (0.70–1.58) |

| $40,000–$74,999 | 29.7 | 1.3 (1.00–1.65) | 1.1 (0.87–1.37) | 1.2 (0.83–1.68) |

| $75,000 or more | 30.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

|

| ||||

| Survey year | ||||

| 2004 | 33.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 2005 | 33.8 | 0.8 (0.56–1.00) | 0.9 (0.71–1.09) | 0.8 (0.59–1.23) |

| 2006 | 33.1 | 1.0 (0.76–1.31) | 0.7 (0.54–0.86) | 1.5 (1.02–2.11) |

The adjusted multinomial logistic model included all the independent variables listed in the first column.

Each hallucinogen use group was compared with adolescents who reported no use of any hallucinogens in the past year.

AOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence intervals; Boldface: p < 0.05.

2.3. Study variables

The survey assessed respondents’ lifetime use of hallucinogens: MDMA (“ecstasy”), LSD, PCP, peyote, mescaline, and psilocybin (Wu et al., 2006, 2008a). Respondents also reported age of first use (onset) of any hallucinogen, the number of days they had used hallucinogens in the previous 12 months, and how recently they had used the hallucinogen. The latter construct was assessed by the question “How long has it been since you last used [name of a hallucinogen]?” We categorized past-year hallucinogen users into two mutually exclusive groups: MDMA users (regardless of whether they used any other type of hallucinogen) and other hallucinogen users who had not used MDMA (Wu et al., 2008a). The total number of days that respondents used any hallucinogens in the past year was classified as 1–11, 12–51 (approximately monthly), and 52 or more days (approximately weekly) to distinguish between experimental (1–11 days) and more regular use (Wu et al., 2008a). The survey did not assess the total number of days that respondents had consumed any specific type of hallucinogen in the past year.

Past-year HUDs (dependence and abuse) were assessed by standardized questions as specified by the DSM-IV (APA, 2000; Wu et al., 2008a). Hallucinogen dependence was measured by the following six criteria: (1) spending a great deal of time over a period of a month obtaining, using, or getting over the effects of hallucinogens; (2) using hallucinogens more often than intended or being unable to maintain limits on use; (3) using the same amount of hallucinogens with decreasing effects or increasing use to get the same desired effects as previously attained; (4) inability to reduce or stop hallucinogen use; (5) continued hallucinogen use despite problems with emotions, nerves, or mental or physical health; and (6) reduced involvement or participation in important activities because of hallucinogen use. The “withdrawal” criterion was not specified as necessary for hallucinogen dependence by the DSM-IV (APA, 2000) and thus was not assessed. The four criteria for abuse included: (1) a serious problem at home, work, or school caused by using hallucinogens; (2) regular consumption of a hallucinogen that put the user in physical danger; (3) repeated use of hallucinogens that led to trouble with the law; and (4) problems with family or friends caused by continued hallucinogen use. Lifetime diagnoses were not assessed by the survey.

Consistent with the DSM-IV (APA, 2000), respondents endorsing at least three criteria of dependence in the past year, regardless of hallucinogen abuse, were classified as exhibiting dependence. Respondents reporting at least one hallucinogen abuse criterion but not meeting criteria for hallucinogen dependence were classified as exhibiting abuse (APA, 2000). Subthreshold dependence or diagnostic orphans (Wu et al., 2008a) included adolescents who responded positively to one or two criteria for dependence but who did not qualify for a diagnosis of dependence or abuse. We created a variable to reflect four mutually exclusive groups of past-year hallucinogen users: hallucinogen dependence, abuse, subthreshold dependence, and use only (i.e., asymptomatic users who did not report any criteriion of HUDs).

Adolescents’ key demographic variables included age, gender, race/ethnicity, student status, and total annual family income (Wu et al., 2006). A categorical survey year variable also was created to examine the potential for yearly variations in hallucinogen use and disorders. Additionally, we examined the five prevalent substance use disorders (i.e., tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and opioid), major depressive episodes, and criminal behavior as potential correlates of HUDs (Gouzoulis-Mayfrank and Daumann, 2006; Parrot, 2001; SAMHSA, 2002; Thomasius et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2006, 2008a, 2009; Yacoubian, 2003). The selection of these variables was based on their previously reported associations with hallucinogen use and on the hypothesis that HUDs (especially dependence) will be associated with substance use disorders and mental health problems. The hypothesized association is assumed to be related to drug users’ tendency to use multiple substances to intensify or modulate the subjective effects of drug use, to attenuate the discomfort or negative affect (e.g., depression, anxiety, and distress) resulting from the after-effects of ecstasy or other drug use, or to self-medicate mental health problems (Boys et al., 2001; Parrott, 2001; Reneman et al., 2006; Winstock et al., 2001). Adolescents’ level of hallucinogen use also was expected to be linked with criminal activities due to their potential associations with a host of risky behaviors (e.g., substance use, behavioral problems, and school problems) (Alati et al., 2008; Jessor, 1998).

Past-year substance use disorders (abuse of or dependence on alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, inhalants, heroin, analgesic opioids, stimulants, sedatives, and tranquilizers) were assessed by standardized questions with reference to DSM-IV criteria (APA, 2000). Past-month nicotine dependence was defined according to the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS) (Shiffman et al., 2004) and Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (Fagerstrom, 1978; Heatherton et al., 1991). Based on NSDUH protocols, nicotine dependence was considered present if respondents met the NDSS or FTND criteria for dependence in the past month. Past-year measure of nicotine dependence was not available. Questions assessing past-year major depressive episodes were based on DSM-IV criteria and adapted from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (Kessler et al., 2005; SAMHSA, 2007a; Wu et al., 2008a). Mental health treatment service utilization was defined as any use of treatment or counseling at any service location in the prior year for emotional or behavioral problems that were not caused by alcohol or drug use (Wu et al., 2006). Criminal behavior included arrests and selling illicit drugs. Past-year arrest was defined as an arrest or booking, excluding minor traffic violations, during the past 12 months (Wu et al., 2008a). Past-year illicit drug selling was defined as having sold illicit drugs during this period (Wu et al., 2008b).

2.4. Data analysis

We first examined demographic characteristics of the adolescents and of hallucinogen users by MDMA use status. Survey year was included as a dummy variable in the analysis to test for yearly variations in hallucinogen use. Multinomial logistic regression analyses were applied to compare the differences in sociodemographic characteristics of MDMA users versus other hallucinogen users. Within the subset of past-year hallucinogen users (n = 1,585), we examined patterns of hallucinogen use, other substance use and disorders, and HUDs by MDMA use status, including subthreshold dependence and profiles of DSM-IV symptoms. As a reference, we also generated the prevalence of other substance use and disorders among drug users who reported no use of hallucinogens (including marijuana, cocaine, inhalants, heroin, or nonmedical use of prescription opioids, stimulants, sedatives, and tranquilizers). To provide a more comprehensive view of the problems of substance use disorders, we also explored the prevalence of comorbid substance use disorders by hallucinogen diagnostic status.

Lastly, multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify the characteristics associated with respondents’ hallucinogen use diagnostic categories (dependence, abuse, subthreshold dependence, and use only). Survey year was included in the model as a control variable due to its significant association with hallucinogen use. To control for potentially confounding effects of age, gender, and race/ethnicity on hallucinogen use, these variables were included in the adjusted model irrespective of their level of significance. Due to the significant association between gender and MDMA use (SAMHSA, 2007b), we also explored the interaction of MDMA use and gender in relation to HUD categories. The interaction term was not significant. All analyses were conducted with SUDAAN 9.0.1 to account for the complex sampling design and resulting design effects of the NSDUH (Research Triangle Institute, 2006).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic characteristics of hallucinogen users

Overall, 2.7% (n = 1,585) of adolescents reported any use of hallucinogen in the past year, and 1.2% reported MDMA use (44% of all past-year hallucinogen users). A similar proportion of MDMA users and of other hallucinogen users reported the use of LSD (22% and 19%, respectively) or PCP (11% and 10%, respectively) in the past year. Past-year use of peyote, mescaline, and psilocybin were not specifically assessed by the survey. MDMA users were more likely than non-hallucinogen users to be female (relative to male), white (relative to African American, Asian/Pacific Islander/native Hawaiian, or Hispanic), aged 16–17 years (relative to aged 12–15 years), non-student (relative to student), and to report a family income of $40,000–$74,999 (relative to $75,000 or more) (Table 1). Compared with other hallucinogen users, MDMA users were more likely to be female, white (relative to African American), aged 16–17 years (relative to aged 12–13 years), and non-students. Elevated odds of MDMA use were noted in the 2006 relative to the 2004 survey.

3.2. Patterns of hallucinogen use

As shown in Table 2, MDMA users were more likely than other hallucinogen users to have a history of LSD (30% vs. 24%), PCP (19% vs. 12%), peyote (9% vs. 5%), and mescaline use (8% vs. 4%) (χ2 test p < 0.05 for each comparison). In contrast, other hallucinogen users were more likely than MDMA users to use psilocybin (59% vs. 46%; χ2 test p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Pattern of hallucinogen use among past-year hallucinogen users aged 12–17 years by MDMA use status (N = 1,585)

| Hallucinogen use status | Past-year MDMA users (n = 646) | Past-year users of other hallucinogens (n = 939) | χ2 or t-test p-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime hallucinogen use, column % (SE) | |||

| MDMA | 100 | …….2 | |

| LSD | 30.3 (2.29) | 23.5 (1.95) | 0.029 |

| PCP | 18.5 (2.09) | 12.4 (1.59) | 0.023 |

| Peyote | 9.2 (1.35) | 4.6 (0.80) | 0.005 |

| Mescaline | 8.2 (1.76) | 3.6 (0.86) | 0.019 |

| Psilocybin | 45.9 (2.69) | 59.3 (1.93) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Number of different hallucinogens ever used,1 % (SE) | |||

| 1 | 40.4 (2.68) | 69.3 (2.30) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 29.9 (2.56) | 21.6 (2.06) | |

| 3 or more | 29.7 (2.14) | 9.1 (1.35) | |

|

| |||

| Number of different hallucinogens ever used,1 mean (SE) | 2.12 (0.05) | 1.05 (0.05) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Cumulative days of hallucinogen use in the past year, % (SE) | |||

| 1–11 | 62.0 (2.23) | 69.2 (2.00) | 0.048 |

| 12–51 | 21.3 (2.04) | 17.9 (1.67) | |

| 52 or more days | 16.7 (2.07) | 12.9 (1.44) | |

|

| |||

| Age of first hallucinogen use, mean (SE) | 14.7 (0.08) | 14.5 (0.08) | NS |

| Age of first MDMA use, mean (SE) | 15.1 (0.07) | 14.5 (0.20) | 0.005 |

| Age of first LSD use, mean (SE) | 14.7 (0.16) | 14.4 (0.18) | NS |

| Age of first PCP use, mean (SE) | 14.2 (0.21) | 14.3 (0.28) | NS |

Sample sizes are unweighted numbers; proportions are weighted figures.

χ2 tests for proportion and t tests for mean; NS: p > 0.05.

A small percentage (6.5%) of past-year users of other hallucinogens reported MDMA use prior to the past year but not in the past year (former MDMA use).

3.3. Patterns of other substance use and disorders

MDMA users also had a higher prevalence of past-year use of alcohol, tobacco, opioids, cocaine, and tranquilizers than users of other hallucinogens (Table 3), who in turn had a higher prevalence of the use of each substance examined than that of drug users who did not use any hallucinogen in the past year. Marijuana (89% among MDMA users), opioids (65%), and cocaine (43%) were frequently used by MDMA users, while marijuana (83%) and opioids (49%) were commonly used by users of other hallucinogens. It is worth noting that, relative to users of other hallucinogens, MDMA users had a higher prevalence of nicotine dependence (41% [95% CI: 35.92–45.99] vs. 25% [95% CI: 21.13–28.51]) and cocaine use disorders (13% [95% CI: 9.56–16.01] vs. 4% [95% CI: 2.76–6.55]). The prevalence of alcohol (19%), nicotine (12%), and each of non-hallucinogen drug use disorders (ranging from 0.08% [heroin] to 14% [marijuana]) were all comparatively lower among drug users who had not used hallucinogens than the two hallucinogen-using groups.

Table 3.

Pattern of substance use and disorders among past-year drug users aged 12–17 years by MDMA use status (N = 11,515)

| Prevalence % (SE) | A: MDMA users (n = 646) | B: Users of other hallucinogens (n = 939) | C: Users of non-hallucinogen drugs1 (n = 9,930) | χ2 test2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any use in the past year | ||||

| Hallucinogens/MDMA | 100 | 100 | 0 | |

| Alcohol | 94.8 (1.18) | 89.5 (1.28) | 74.3 (0.67) | A > B > C |

| Tobacco | 92.9 (1.33) | 82.6 (1.78) | 59.2 (0.62) | A > B > C |

| Marijuana | 88.5 (1.46) | 82.6 (1.86) | 65.1 (0.67) | AB > C |

| Opioids/analgesics 3 | 65.2 (2.46) | 49.3 (2.11) | 32.4 (0.67) | A > B > C |

| Cocaine | 43.2 (2.45) | 22.2 (1.88) | 4.7 (0.30) | A > B > C |

| Tranquilizers 3 | 36.3 (2.46) | 23.8 (1.93) | 7.0 (0.32) | A > B > C |

| Stimulants 3 | 29.1(2.44) | 22.3 (1.82) | 7.4 (0.30) | AB > C |

| Inhalants | 25.1 (2.30) | 27.7 (1.93) | 21.8 (0.57) | B > C |

| Heroin | 6.3 (1.23) | 2.5 (0.69) | 0.3 (0.05) | AB > C |

| Sedatives 3 | 4.8 (1.08) | 3.7 (0.86) | 2.0 (0.19) | A > C |

|

| ||||

| Abuse or dependence4 | ||||

| Hallucinogens/MDMA | 22.8 (2.35) | 12.8 (1.57) | 0 | A > B |

| Marijuana | 47.0 (2.68) | 36.9 (2.50) | 14.3 (0.50) | AB > C |

| Alcohol | 43.1 (2.79) | 37.0 (2.35) | 18.7 (0.53) | AB > C |

| Nicotine dependence4 | 40.9 (2.55) | 24.6 (1.87) | 12.4 (0.42) | A > B > C |

| Opioids/analgesics | 16.0 (1.92) | 12.2 (1.84) | 4.7 (0.31) | AB > C |

| Cocaine | 12.5 (1.64) | 4.3 (0.93) | 0.8 (0.01) | A > B > C |

| Tranquilizers | 6.3 (1.17) | 4.1 (0.95) | 0.8 (0.11) | AB > C |

| Stimulants | 5.8 (1.06) | 4.9 (1.13) | 1.0 (0.14) | AB > C |

| Inhalants | 4.1 (1.03) | 6.0 (0.96) | 1.9 (0.21) | AB > C |

| Heroin | 1.8 (0.66) | 1.02 (0.50) | 0.08 (0.03) | AB > C |

| Sedatives | 1.4 (0.58) | 1.5 (0.68) | 0.4 (0.09) | AB > C |

Users of non-hallucinogen drugs = past-year drug users (users of marijuana, cocaine, inhalants, heroin, or nonmedical users of opioids, stimulants, sedatives, or tranquilizers) who did not use any hallucinogen in the past year.

P < 0.05.

Nonmedical use of prescription drugs.

Except for past-month nicotine dependence; all the other substances refer to past-year abuse or dependence. The prevalence of nicotine dependence was expected to be higher than the current rate for past-month if it was based on a 12-month period.

3.4. DSM-IV symptoms of HUDs

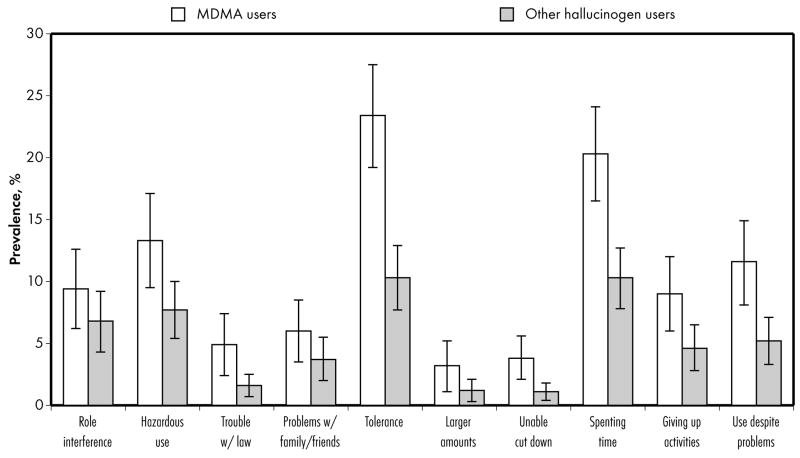

We then evaluated the specific DSM-IV symptoms that affected hallucinogen users. Of the ten criteria specified by the DSM-IV for HUDs (Figure 1), MDMA users exhibited a significantly higher prevalence than other hallucinogen users with respect to five criteria: (1) trouble with the law, (2) tolerance, (3) inability to cut down, (4) spending a great deal of time using, and (5) continuing to use despite resulting psychological or physical problems.

Figure 1.

The prevalence of specific DSM-IV symptoms among MDMA (open bars) and other hallucinogen (shaded bars) users.

3.5. Prevalence of HUDs and subthreshold dependence

Among all adolescents (N = 55,286), 0.5% met criteria for a past-year HUD (dependence, 0.2%; abuse, 0.3%), and there were no significant yearly variations in the prevalence of abuse or dependence across survey years. However, the prevalence of HUD symptoms among past-year hallucinogen users (n = 1,585) was noteworthy. Overall, 25.3% and 15.5% of hallucinogen users had at least one criterion of dependence and abuse, respectively (data not shown). Based on the DSM-IV (APA, 2000) (Table 4), 17% (n = 256) of hallucinogen users met criteria for a past-year HUD (dependence, 6.7%; abuse, 10.3%), and an additional 13.2% (n = 201) exhibited subthreshold dependence (one or two criteria of dependence and no abuse). MDMA users had a higher prevalence of dependence (11% [95% CI: 8.24–14.8]) than other hallucinogen users (3.5% [95% CI: 2.22–5.43]).

Table 4.

Prevalence of hallucinogen use disorders among past-year hallucinogen users aged 12–17 years: by MDMA use status (N = 1,585)

| Prevalence % (95% confidence interval) | Overall | A: MDMA users | B: Other hallucinogen users | χ2 test1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 1,585 | 646 | 939 | |

| Dependence | 6.7 (5.19–8.69) | 11.1 (8.24–14.81) | 3.5 (2.22–5.43) | A > B |

| Abuse | 10.3 (8.53–12.48) | 11.7 (8.77–15.50) | 9.3 (6.89–12.47) | NS |

| Subthreshold dependence | 13.2 (11.17–15.56) | 15.7 (12.43–19.65) | 11.4 (9.09–14.11) | NS |

| Use without DSM-IV criterion symptom | 69.7 (66.74–72.55) | 61.5 (56.52–66.18) | 75.9 (71.96–79.34) | A < B |

Sample sizes are unweighted numbers; proportions are weighted figures.

χ2 (df) test = 29.14 (3), p < 0.001.

NS: p > 0.05.

3.6. Comorbid substance use disorders by HUD status

Table 5 describes the prevalence of comorbid disorders by HUD status. The majority of adolescents with hallucinogen dependence or abuse also had marijuana or alcohol use disorders (> 60%), and to a lesser extent, nicotine dependence and opioid use disorders (> 30%). The dependence group resembled the abuse group in comorbid disorders, while the dependence group had a higher prevalence of cocaine and inhalant use disorders than the subthreshold dependence group. The subthreshold dependence group had a higher prevalence of marijuana and cocaine use disorders than the hallucinogen use only group.

Table 5.

Prevalence of substance use disorders among adolescent hallucinogen users aged 12–17 years by hallucinogen diagnostic status (N = 1,585)

| Hallucinogen use status, % (SE) | A: Hallucinogen dependence | B: Hallucinogen abuse | C: Hallucinogen subthreshold dependence | D: Use without DSM-IV symptom | χ2 test1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 95 | 161 | 201 | 1128 | |

|

| |||||

| Abuse or dependence2 | |||||

| Marijuana | 68.8 (5.92) | 64.7 (5.30) | 42.3 (4.40) | 34.8 (1.91) | AB > C > D |

| Alcohol | 67.9 (5.88) | 63.6 (5.72) | 46.7 (4.68) | 31.9 (2.02) | A > D |

| Nicotine dependence2 | 44.7 (6.30) | 32.9 (4.91) | 38.2 (4.64) | 28.8 (1.98) | NS |

| Opioids/analgesics | 38.9 (6.20) | 39.1 (6.37) | 9.8 (2.82) | 8.4 (1.26) | AB > CD |

| Cocaine | 27.9 (5.38) | 15.1 (3.56) | 10.1 (2.59) | 4.3 (0.82) | ABC > D, A >C |

| Tranquilizers | 11.1 (4.54) | 20.5 (5.37) | 5.0 (2.10) | 2.2 (0.60) | AB > D |

| Stimulants | 17.4 (3.98) | 16.6 (4.62) | 5.8 (2.47) | 2.3 (0.44) | AB > D |

| Inhalants | 19.1 (5.00) | 15.3 (3.80) | 4.1 (1.94) | 2.6 (0.57) | A > CD |

| Heroin | 10.1 (3.83) | 3.1 (2.46) | 0.5 (0.51) | 0.4 (0.18) | A > D |

| Sedatives | 5.4 (3.16) | 7.5 (3.80) | 1.2 (0.69) | 0.2 (0.13) | AB > D |

P < 0.05; NS: p > 0.05.

Except for past-month nicotine dependence; all the other substances refer to past-year abuse or dependence. The prevalence of nicotine dependence was expected to be higher than the current rate for past-month if it was based on a 12-month period.

3.7. Adjusted odds ratios of HUDs and subthreshold dependence

Table 6 summarizes results from multinomial logistic regression of HUDs (dependence, abuse, subthreshold dependence, and use only). We first examined the bivariate association for each covariate and then included in the adjusted model those covariates that were found to be significantly associated with the dependent variable. School status, family income, and past-year major depressive episode were not associated with HUD status in the unadjusted analysis. Age of first hallucinogen use, selling drugs, and being booked or arrested were not associated with HUD status in the model including variables of substance use disorders and thus were excluded from the analysis.

Table 6.

Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of hallucinogen use disorders among past-year hallucinogen users aged 12–17 years (N = 1,585)

| Adjusted categorical multinomial logistic regression model1: AOR (95% CI) | Dependence vs. use only | Abuse vs. use only | Subthreshold dependence vs. use only | Dependence vs. abuse | Dependence vs. subthreshold dependence | Abuse vs. subthreshold dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (vs. male) | ||||||

| Female | 1.4 (0.86–2.41) | 1.0 (0.62–1.57) | 1.8 (1.08–2.89) | 1.5 (0.80–2.65) | 0.8 (0.45–1.49) | 0.5 (0.28–1.05) |

|

| ||||||

| Age group, y (vs. 16–17) | ||||||

| 12–13 | 1.7 (0.38–7.62) | 2.3 (0.91–5.78) | 3.4 (1.64–7.09) | 0.8 (0.18–3.02) | 0.5 (0.14–2.07) | 0.7 (0.27–1.75) |

| 14–15 | 1.6 (0.81–2.99) | 1.0 (0.61–1.65) | 0.8 (0.45–1.36) | 1.6 (0.73–3.31) | 2.1 (0.95–4.68) | 1.4 (0.64–2.85) |

|

| ||||||

| Race/ethnicity (vs. white) | ||||||

| African American | 1.3 (0.34–5.24) | 0.7 (0.21–2.59) | 0.4 (0.14–1.25) | 1.8 (0.34–9.36) | 3.6 (0.68–18.67) | 2.0 (0.41–10.06) |

| American Indian/Alaska native | 2.1 (0.63–6.94) | 6.5 (1.18–36.15) | 2.3 (0.63–8.04) | 0.3 (0.06–1.74) | 0.9 (0.16–5.15) | 3.0 (0.57–15.90) |

| Asian/Pac. Islander/nat. Hawaiian | 0.3 (0.02–3.52) | 0.5 (0.08–2.81) | 2.4 (0.34–16.98) | 0.5 (0.10–2.07) | 0.1 (0.01–1.68) | 0.2 (0.03–1.19) |

| Multi-racial | 0.1 (0.03–0.43) | 1.2 (0.28–5.04) | 0.3 (0.10–1.15) | 0.1 (0.02–0.43) | 0.3 (0.06–2.04) | 4.4 (1.09–17.81) |

| Hispanic | 2.1 (0.78–5.44) | 1.2 (0.51–2.92) | 1.0 (0.46–2.05) | 1.7 (0.56–4.88) | 2.1 (0.61–7.01) | 1.2 (0.42–3.63) |

|

| ||||||

| Days of hallucinogen use (vs. 1–11) | ||||||

| 12–51 | 2.3 (1.02–5.08) | 1.1 (0.56–1.98) | 1.6 (1.04–2.46) | 2.2 (0.85–5.62) | 1.5 (0.57–3.67) | 0.7 (0.34–1.39) |

| 52 or more days | 5.5 (2.37–12.75) | 2.7 (1.41–5.22) | 2.4 (1.66–6.92) | 2.1 (0.89–4.86) | 1.8 (0.64–4.80) | 0.8 (0.35–1.92) |

|

| ||||||

| MDMA use (vs. other hallucinogen use) | ||||||

| Yes | 3.0 (1.59–5.68) | 1.7 (0.97–3.09) | 1.4 (0.88–2.07) | 1.8 (0.82–3.78) | 2.2 (1.05–4.77) | 1.3 (0.65–2.51) |

|

| ||||||

| Number of types of hallucinogens used (vs. one) | ||||||

| 2 | 2.2 (0.95–5.17) | 1.6 (0.85–3.12) | 1.2 (0.70–2.08) | 1.3 (0.55–3.20) | 1.7 (0.66–4.29) | 1.3 (0.60–2.77) |

| 3 or more types | 2.7 (1.13–6.38) | 1.4 (0.66–2.82) | 2.4 (1.37–4.35) | 1.9 (0.74–4.67) | 1.1 (0.39–2.99) | 0.6 (0.25–1.32) |

|

| ||||||

| Using mental health services (vs. no) | ||||||

| Yes | 2.6 (1.23–5.36) | 1.6 (0.99–2.50) | 0.9 (0.58–1.40) | 1.6 (0.74–3.29) | 2.9 (1.34–6.06) | 1.7 (1.00–3.00) |

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol use disorder (vs. no) | ||||||

| Yes | 2.4 (1.25–4.51) | 2.3 (1.40–3.99) | 1.8 (1.21–2.77) | 1.0 (0.46–2.18) | 1.3 (0.61–2.54) | 1.3 (0.65–2.41) |

|

| ||||||

| Marijuana use disorder (vs. no) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.9 (0.93–4.05) | 1.9 (1.13–3.11) | 1.2 (0.77–1.84) | 1.0 (0.43–2.51) | 1.6 (0.72–3.56) | 1.6 (0.92–2.81) |

|

| ||||||

| Cocaine use disorder (vs. no) | ||||||

| Yes | 2.3 (1.01–5.39) | 1.4 (0.55–3.35) | 1.2 (0.54–2.59) | 1.8 (0.62–4.96) | 2.0 (0.79–5.05) | 1.2 (0.42–2.98) |

|

| ||||||

| Opioid use disorder (vs. no) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.9 (0.86–4.19) | 3.4 (1.80–6.51) | 0.6 (0.28–1.43) | 0.6 (0.22–1.40) | 2.6 (1.01–6.90) | 4.9 (1.99–12.12) |

The adjusted model controlled for the survey year and included variables listed in the first column. Family income, student status, arrests for criminal activities, selling illicit drugs, major depression, tobacco dependence, and age of onset of hallucinogen use were tested but were not significant and were not included in the adjusted model.

Boldface: p < 0.05.

Dependence

Compared with hallucinogen use only, dependence was associated with being white (relative to being multi-racial), use of hallucinogens for 12 or more days in the past year, past-year MDMA use, use of three or more types of hallucinogens, use of mental health services, and substance use disorders related to alcohol and cocaine.

Abuse

Compared with hallucinogen use only, increased odds of abuse were noted among American Indians/Alaska natives (relative to whites), use of hallucinogens for ≥52 days, and those with a substance use disorder related to use of alcohol, marijuana, and opioids.

Subthreshold dependence

Compared with hallucinogen use only, females and young adolescents aged 12–13 years (relative to those aged 16–17 years) were likely to exhibit subthreshold dependence. Use of hallucinogens for 12 or more days, use of three or more types of hallucinogens, and alcohol use disorders were also associated with subthreshold dependence.

Dependence vs. abuse

Relative to abuse, whites had greater odds of dependence as compared with those reporting multi-racial backgrounds.

Dependence vs. subthreshold dependence

Relative to subthreshold dependence, increased odds of dependence were noted among MDMA users, users of mental health services, and those with an opioid use disorder.

Abuse vs. subthreshold dependence

Relative to subthreshold dependence, increased odds of abuse were found among respondents with multi-racial backgrounds (compared with whites), users of mental health services, and those meeting criteria for an opioid use disorder.

4. Discussion

Approximately 3% of adolescents nationally had used hallucinogens in the past year, and 44% of hallucinogen users had used MDMA within the same period. While the prevalence of HUDs among all adolescents was low (< 1%), almost one third (30%) of past-year hallucinogen users reported symptoms of HUDs. Overall, 17% of hallucinogen users met criteria for a past-year HUD; an additional 13% exhibited subthreshold dependence. Adolescents in the latter group, particularly females and young adolescents aged 12–13, may be overlooked in epidemiological studies because they do not meet diagnostic criteria as specified by the DSM-IV and yet exhibit problems related to their substance use. Failure to include them in studies may underestimate the prevalence of hallucinogen use-related problems in the adolescent population.

4.1. MDMA users versus other hallucinogen users

The study’s most salient finding concerns the high prevalence of HUDs and other substance use disorders (i.e., nicotine, alcohol, and marijuana) among MDMA users. More than one in five MDMA users (23%) met criteria for an HUD. Additionally, approximately one in six (16%) exhibited subthreshold dependence. Even after adjusting for the effects of other substance use disorders, the frequency and type of hallucinogens used, and past-year use of mental health treatment services, MDMA users were three times as likely as users of other hallucinogens to exhibit dependence. In addition, MDMA users were more likely to report hallucinogen use-related consequences (trouble with the law), physical dependence (tolerance), and compulsive hallucinogen-seeking behaviors (inability to cut down and spending a great deal of time using hallucinogens), despite the negative impact of use on their mental or physical heath (impaired cognition). In line with these findings, Stone et al. (2006) found that young MDMA users were twice as likely as LSD users to develop an hallucinogen dependence syndrome. This comparatively high rate of dependence symptoms among MDMA users could be related in part to their greater use of hallucinogens than other hallucinogen users. For example, MDMA users in this sample appeared to have consumed more types of hallucinogens than other hallucinogen users and that hallucinogen users who used hallucinogens for ≥52 days in the past year (weekly) were 5.5 times as likely to meet criteria for dependence. Yen and Hsu (2007) also reported that greater use of MDMA was significantly associated with more symptoms of dependence on MDMA (e.g., tolerance, spending a great deal of time using, and continuing MDMA use despite having problems resulting from such use).

Further, chronic tolerance to MDMA (i.e., reduction in subjective efficacy) often develops among recreational MDMA users; once it occurs, the users take a larger amount of the drug to achieve the same effects originally obtained by a smaller dosage (Parrott, 2005). This chronic tolerance could lead to dosage escalation and binge use of MDMA, which in turn, might intensify dependence symptoms and consequences from MDMA use as well as the use of other substances such as marijuana and opioids to modulate the negative effects from post-MDMA use (Parrott, 2001, 2005). MDMA’s serotonergic neurotoxic effects on human brains may involve in the development of chronic tolerance to MDMA and dosage escalation in drug users (Parrott, 2005). In this study, tolerance is one of the most prevalent HUD symptoms among MDMA users (23%; 95% CI: 19.2–27.5%), and it is more prevalent than among other hallucinogen users (10%; 95% CI: 7.7–12.9%).

These findings of HUDs differ somewhat from a previous report on HUDs among adult hallucinogen users aged 18 years or older (Wu et al., 2008a). Compared with adolescents in this study, adult users appeared to have a lower prevalence of HUD: dependence (3% vs. 7%), abuse (5% vs. 10%), and subthreshold dependence (10% vs. 13%). Further, MDMA use among adults was not associated with HUDs. The higher prevalence of HUDs among adolescents may be related to their more active use of hallucinogens than adults (Wu et al., 2008a) or to the possibility that adolescents’ developing brains are generally more susceptible to the effects of hallucinogen/MDMA use. As with any other U.S. national survey, however, the exact amount of MDMA and other hallucinogens consumed was not assessed by the NSDUH. Nonetheless, our findings reveal a high prevalence of HUDs (23%) and subthreshold dependence (16%) among adolescent MDMA users.

There are also some important differences between MDMA and other hallucinogen users. While MDMA users were more likely than users of other hallucinogens to have left school (i.e., non-students) and consumed a wide variety of substances in the past year, they were less likely to use psilocybin. This finding that psilocybin was the most commonly used hallucinogen among non-MDMA users deserves further research. Like heroine or MDMA, psilocybin is classified as a Schedule I drug indicating that it has a high potential for abuse and has no approved medical use (NIDA, 2009). Case reports indicate that repeated psilocybin use impairs memory and increases the risk for psychiatric illnesses (NIDA, 2008b). However, very little is presently known about the extent of past-year psilocybin use because psilocybin is combined with other non-LSD hallucinogens into one broad category in the MTF surveys (Johnston et al., 2007b), and the NSDUH does not specifically assess past-year psilocybin use. Given its relatively prevalent use in adolescents, past-year psilocybin use warrants individual assessment in national surveys in order to better monitor its use, demographic profiles, and related problems.

These findings also expand on previous studies of drug use by suggesting that adolescent MDMA users not only had a higher prevalence of nicotine dependence and cocaine use disorders than users of other hallucinogens, but also have a higher prevalence of disorders related to the use of all the other substances examined than non-hallucinogen drug users (Pedersen and Skrondal, 1999; Wu et al., 2006; Yacoubian, 2003). Recent research has suggested a bidirectional association between MDMA use and initiation of other substances. Martins et al. (2007) found that prior use of marijuana, cocaine, and heroin predicted the onset of MDMA use; prior MDMA use also predicted later use of marijuana, cocaine, and heroin. Moreover, it appeared that marijuana use tended to precede the use of MDMA, while cocaine and heroin use was particularly likely to follow initiation of MDMA use (Martins et al., 2007). Additionally, Lieb et al. (2002) found that the majority of subjects with an alcohol, nicotine, or any drug use disorder initiated their MDMA use after their onsets of these disorders, and that a smaller proportion initiated their MDMA use before their onsets of these disorders. Further, subjects with a history of mental disorder also exhibited an increased risk for initiating MDMA use subsequently. Therefore, MDMA use not only is a manifestation of early substance use or mental health problems that tend to co-exist with other behavioral problems (Alati et al., 2008; Lieb et al., 2002) but also confers a risk for subsequent drug use and mental disorders (Lieb et al., 2002; Martins et al., 2007). Regardless of the temporal sequence of drug use, heavy MDMA polydrug users are likely to have the worst psychiatric consequences (Soar et al., 2001).

There are several potential explanations for polysubstance use. Studies have suggested that an increased scope of substance use such as alcohol, marijuana, or other drugs may increase the likelihood of MDMA use among drug users by increasing their propensity to use multiple substances in order to enhance subjective effects of drug use or to relieve discomfort or withdrawal symptoms from after-effects of drug use (Boys et al., 2001; Parrott, 2001; Reneman et al., 2006; Winstock, et al., 2001). Alcohol, marijuana, and opioids are reportedly used by drug users to relieve discomfort associated with post-MDMA comedown (Parrott, 2001; Winstock et al., 2001). Additionally, use of multiple substances can be influenced through chronic tolerance to MDMA or through cross-tolerance to different stimulants (Parrott, 2005; Parrott et al., 2004). In such circumstances, dosage escalation may occur across different stimulants in an attempt to maintain a positive on-drug experience in the face of reducing efficacy, but this greater intensity of usage also enhances drug-related adverse symptoms or consequences (Parrott, 2005). Therefore, repeated drug users may need to balance their desire for an optimal on-drug experience with a need to minimize negative effects from post-drug use, which may account in part for polysubstance use by some MDMA users (Parrott, 2005).

4.2. Threshold versus subthreshold categories

Consistent with prior findings pertinent to marijuana (Degenhardt et al., 2002), analgesic opioids (Wu et al., 2008b), and hallucinogens (Wu et al., 2008a), we found a comparatively large proportion of hallucinogen users who reported one or two dependence criteria but were not classified with a HUD by the DSM-IV. These diagnostic orphans constituted 16% of MDMA users and 11% of other hallucinogen users. Compared with asymptomatic hallucinogen users, we found that females, young adolescents aged 12–13 years, frequent users of hallucinogens (≥12 days), users of multiple hallucinogens, and those with an alcohol use disorder had greater odds of being classified as diagnostic orphans. Given their comparatively high prevalence, young age, and problematic substance use, this group warrants further investigation to elucidate their clinical courses, intervention needs, and relevancy for the next iteration of the DSM (Wu et al., 2008a, 2008b).

Relative to the hallucinogen use only group (asymptomatic users), we found that regular use of hallucinogens (≥52 days), alcohol use disorder, and drug use disorder (marijuana and opioid for the abuse group; cocaine for the dependence group) were associated with increased odds of abuse and of dependence. Thus, both disorder groups are likely to have consumed more hallucinogens and other substances than the hallucinogen use only group. In addition, the dependence group differed from the use only and subthreshold dependence groups in past-year MDMA use, suggesting that the dependence group is more likely to use MDMA recently. These findings also lend some support for the distinction between those without versus with a HUD: the latter group also is likely to use treatment for mental health problems and to exhibit an opioid use disorder in the past year as compared with the subthreshold group. However, the DSM-IV’s distinction between the abuse (using one criterion threshold) and the dependence (using three criteria threshold) groups is not clearly observed because they show great similarities in substance use characteristics, suggesting that they tend to classify two similar subgroups of hallucinogen users.

Taken together, these findings support the presence of polysubstance use among young hallucinogen users (Rickert et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2006; Yacoubian, 2003). They further reveal that adolescents with a HUD are more likely than those without a HUD to have co-existing substance use disorders and mental health problems that warrant clinical monitoring and intervention to reduce potential consequences from substance abuse. Additionally, while nonmedical use of opioids among MDMA users has received little research attention, study results indicate that opioids are the second most likely drug class (following marijuana) to be used by all drug users and particularly to be abused by those with a HUD (39% of them with an opioid use disorder). It hence confirms recent reports on the increased rate of nonmedical use of opioids among adolescents and its association with substance use disorders (Wu et al., 2008b, 2008c).

Finally, the increasing rate of MDMA use among adolescent girls deserves more research and monitoring. Females are more likely than males to initiate MDMA use, while males are likely to initiate use of other hallucinogens (SAMHSA, 2007b). We also found that females have elevated odds of using MDMA, but lower odds of using other hallucinogens as compared with melas. Although we did not find that the association between HUDs and gender was moderated by MDMA use, investigators have suggested that sex-related differences in metabolism, brain suture, or hormones may make females more susceptible to the neurotoxic effect of MDMA use than males (Allott and Redman, 2007). The reasons for the recent increase in MDMA use by females are not known; nonetheless, research is needed to monitor their trends in MDMA use over time and to elucidate which of their characteristics contribute most to this drug use.

4.3. Limitations and strengths

These findings should be interpreted with some caution. First, substance use behaviors were obtained from adolescents’ self-reports, which are subject to memory errors and under-reporting (Gfroerer et al., 1997). Due to the large scale of the NSDUH, substance use disorders were assessed by standardized questions using computer-assisted interviewing methods, but they were not validated by clinicians. Clinical validation is often impractical and very costly for a large national survey (SAMHSA, 2008). It is also worth noting that the assessment for nicotine dependence was based on the past 30 days. The prevalence of nicotine dependence was expected to be higher than the past-month estimate if it was based on a 12-month period. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the NSDUH precludes making inferences of causal relationships from our findings. The high prevalence of substance use disorders among hallucinogen users in general points to the need to understand the role of hallucinogen use in the context of other drug use problems. Third, these findings cannot be generalized to adolescents who were institutionalized or homeless on the days that the survey was administered because the NSDUH did not interview them. Fourth, because diagnostic information was collected for the class of the drugs, it is difficult to draw broad conclusions about specific adverse effects. However, this is a common practice in all known U.S. national surveys of substance use disorders that limits the interpretability of research on this area. Last, like any other large U.S. survey, the NSDUH does not collect data on either purity or dosage of MDMA tablets, both of which affect drug use behaviors and consequences (Parrott, 2004; Thomasius et al., 2005).

This study also has noteworthy strengths. It represents the first national study of the prevalence and correlates of HUDs and subthreshold dependence among adolescents. Study data were collected with the most sophisticated technology available—a combination of computer-assisted personal interviewing and audio computer-assisted self-interviewing—to increase adolescents’ reporting of sensitive and illegal drug use behaviors (Turner et al., 1998). The study sample also has a high degree of generalizability because it constitutes the largest of its kind representing non-institutionalized American adolescents. Further, the sample size was large enough to allow us to determine the magnitude of HUDs by MDMA use status and to adjust analytically for other substance use disorders and patterns of hallucinogen use.

4.4. Implications and Conclusions

In this national sample of adolescents, one in six hallucinogen users met criteria for a past-year HUD. There is a high prevalence of HUDs (23%) and subthreshold dependence (16%) among MDMA users. Study results suggest that adolescent MDMA users not only are at risk for exhibiting hallucinogen dependence but also are likely to use multiple substances and meet criteria for other substance use disorders within a same 12-month period. These findings have important implications. First, psychiatric disorders not only increase the risk for MDMA use but also can occur following MDMA use (Lieb et al., 2002; Soar et al., 2006). In particular, the co-usage of MDMA and other substances is likely to enhance subsequent psychiatric disturbances and cognitive impairments, possibly through the influence of greater amounts of substances taken, serotonergic neurotoxicity of MDMA (depletion of serotonin), potentially multiplicative effects of multiple drugs, and substance-induced mental and cognitive disorders (Parrott, 2006; Soar et al., 2006; Thomasius et al., 2005). Active MDMA users thus should be assessed or screened regularly for comorbid psychiatric and health problems and be intervened as appropriate to reduce their adverse consequences. Given the pervasiveness of their substance use, adolescent MDMA users should benefit from such medical monitoring. Second, considering the increasing use of MDMA among youth and females (Johnston et al., 2007a, 2007b; SAMHSA, 2007b) and its potential lasting neurotoxic effects on young drug users such as memory deficits, elevated impulsiveness, and mood/anxiety disorders (Montoya et al., 2002; Parrott, 2006; Reneman et al., 2006), research is clearly needed to monitor trends in MDMA use in these groups and to elucidate factors and processes that place MDMA users at risk for continuing drug use. Finally, MDMA is now the most prevalent emerging drug of use in adolescents (Wu et al., 2006), but there are no specific behavioral or pharmacological treatments for MDMA abuse or dependence (NIDA, 2006). Given its potential for producing lasting psychiatric disturbances, there is a need for identifying effective prevention and treatment interventions for MDMA use and addiction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in large part by the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (R01DA019623 and R01DA019901, Li-Tzy Wu), and partially supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse: K24DA022288 (Roger D. Weiss) and HHSN271200522071C (Dan G. Blazer). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive and the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research provided the public use data files for NSDUH, which was sponsored by Office of Applied Studies of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Dr. Wu designed the study, conducted the analysis, and wrote the first draft. Drs. Ringwalt, Weiss, and Blazer contributed to the interpretation and revisions of the paper. Dr. Weiss has received research funding from Eli Lilly and Company and has consulted to Titan Pharmaceuticals and Novartis. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors, not of any sponsoring agency. We thank Amanda McMillan for her editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alati R, Kinner SA, Hayatbakhsh MR, Mamun AA, Najman JM, Williams GM. Pathways to ecstasy use in young adults: anxiety, depression or behavioural deviance? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92(1–3):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allott K, Redman J. Are there sex differences associated with the effects of ecstasy/3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:327–347. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boys A, Marsden J, Strang J. Understanding reasons for drug use amongst young people: a functional perspective. Health Educ Res. 2001;16:457–469. doi: 10.1093/her/16.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM. New methods of treatment efficacy research: bridging clinical research and clinical practice. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21:352–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Womack SB, Compton WM, Ben-Abdallah A. Ecstasy abuse and dependence among adolescents and young adults: applicability and reliability of DSM-IV criteria. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2001;16:599–606. doi: 10.1002/hup.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cregg MT, Tracey JA. Ecstasy abuse in Ireland. Irish Med J. 1993;86:118–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Lynskey M, Coffey C, Patton G. ‘Diagnostic orphans’ among young adult cannabis users: persons who report dependence symptoms but do not meet diagnostic criteria. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;67:205–212. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng M, Schuckit M, Smith T. A five-year prospective study of diagnostic orphans for alcohol use disorders. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:227–234. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gfroerer J, Wright D, Kopstein A. Prevalence of youth substance use: the impact of methodological differences between two national surveys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:19–30. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav. 1978;3:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E, Daumann J. The confounding problem of polydrug use in recreational ecstasy/MDMA users: a brief overview. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(2):188–193. doi: 10.1177/0269881106059939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudelsky GA, Yamamoto BK. Actions of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) on cerebral dopaminergic, serotonergic and cholinergic neurons. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Paykin A. Dependence symptoms but no diagnosis: diagnostic ‘orphans’ in a community sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Paykin A. Dependence symptoms but no diagnosis: diagnostic ‘orphans’ in a 1992 national sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;53:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. New perspectives on adolescent risk behavior. In: Jessor R, editor. New Perspectives on Adolescent Risk Behavior. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Overall, illicit drug use by American teens continues gradual decline in 2007. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan News Service; 2007a. [Accessed March 30, 2008]. [online]. Available at: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pressreleases/07drugpr_complete.pdf”. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2006. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Various stimulant drugs show continuing gradual declines among teens in 2008, most illicit drugs hold steady. University of Michigan News Service; Ann Arbor, MI: 2008. [Accessed on March 23, 2009]. Available at: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pressreleases/08drugpr.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb R, Schuetz CG, Pfister H, von Sydow K, Wittchen H. Mental disorders in ecstasy users: a prospective-longitudinal investigation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68:195–207. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Ghandour LA, Chilcoat HD. Pathways between ecstasy initiation and other drug use. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1511–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya AG, Sorrentino R, Lukas SE, Price BH. Long-term neuropsychiatric consequences of “ecstasy” (MDMA): a review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2002;10:212–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Accessed September 10, 2008];National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, Survey Questionnaire Index, Wave 1. 2007 Available at: http://www.nesarc.niaaa.nih.gov/questionnaire.html.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Accessed October 15, 2008];MDMA (Ecstasy) Abuse. NIDA Research Report Series. 2006 Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/PDF/RRmdma.pdf.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Addiction: drugs, brains, and behavior—the science of addiction. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2008a. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Hallucinogens: LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP. National Institutes of Health – U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008b. [Accessed April 23, 2009]. Available at: http://www.nida.nih.gov/pdf/infofacts/Hallucinogens08.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Commonly abused drugs. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. [Accessed April 23, 2009]. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/PDF/CADChart.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC. Human psychopharmacology of ecstasy (MDMA): a review of 15 years of empirical research. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2001;16:557–577. doi: 10.1002/hup.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC. Is ecstasy MDMA? A review of the proportion of ecstasy tablets containing MDMA, their dosage levels, and the changing perceptions of purity. Psychopharmacology. 2004;173:234–241. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1712-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC, Morinan A, Moss M, Scholey A. Understanding Drugs and Behaviour. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC. Chronic tolerance to recreational MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) or ecstasy. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19:71–83. doi: 10.1177/0269881105048900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC. MDMA in humans: factors which affect the neuropsychobiological profiles of recreational ecstasy users, the integrative role of bioenergetic stress. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:147–163. doi: 10.1177/0269881106063268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MM, Wright DW, Ratcliff JJ, Miller MA. Shedding new light on the “safe” club drug: methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy)-related fatalities. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:208–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen W, Skrondal A. Ecstasy and new patterns of drug use: a normal population study. Addiction. 1999;94(11):1695–1706. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941116957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reneman L, de Win MM, van den Brink W, Booij J, den Heeten GJ. Neuroimaging findings with MDMA/ecstasy: technical aspects, conceptual issues and future prospects. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:164–175. doi: 10.1177/0269881106061515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN User’s Manual, Release 9.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rickert VI, Siqueira LM, Dale T, Wiemann CM. Prevalence and risk factors for LSD use among young women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2003;16:67–75. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(03)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB. Substance dependence and non-dependence in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD): can an identical conceptualization be achieved? Addiction. 2006;101:48–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarr M, Bucholz K, Phelps D. Using cluster analysis of alcohol use disorders to investigate ‘diagnostic orphans’: subjects with alcohol dependence symptoms but no diagnosis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60:295–302. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano F, Oyefeso A, Corkery J, Cobain K, Jambert-Gray R, Martinotti G, Ghodse AH. Death rates from ecstasy (MDMA, MDA) and polydrug use in England and Wales 1996–2002. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:519–524. doi: 10.1002/hup.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ, Hickcox M. The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale: A multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:327–348. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soar K, Turner JJ, Parrott AC. Problematic versus non-problematic ecstasy/MDMA use: the influence of drug usage patterns and pre-existing psychiatric factors. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:417–424. doi: 10.1177/0269881106063274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AL, Storr CL, Anthony JC. Evidence for a hallucinogen dependence syndrome developing soon after onset of hallucinogen use during adolescence. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2006;15:116–130. doi: 10.1002/mpr.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Club Drugs, 2001 Update. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services; 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The NSDUH Report: Patterns of Hallucinogen Use and Initiation: 2004 and 2005. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services; 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thomasius R, Petersen KU, Zapletalova P, Wartberg L, Zeichner D, Schmoldt A. Mental disorders in current and former heavy ecstasy (MDMA) users. Addiction. 2005;100:1310–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstock AR, Griffiths P, Stewart D. Drugs and the dance music scene: a survey of current drug use patterns among a ample of dance music enthusiasts in the UK. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;64(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Schlenger WE, Galvin DM. Concurrent use of methamphetamine, MDMA, LSD, ketamine, GHB, and flunitrazepam among American youths. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Ringwalt CL, Mannelli P, Patkar AA. Hallucinogen use disorders among adult users of MDMA and other hallucinogens. Am J Addict. 2008a;17:354–363. doi: 10.1080/10550490802269064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Ringwalt CL, Mannelli P, Patkar AA. Prescription pain reliever abuse and dependence among adolescents: a nationally representative study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008b;47(9):1020–1029. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817eed4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Pilowsky DJ, Patkar AA. Non-prescribed use of pain relievers among adolescents in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008c;94(1–3):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Parrott AC, Ringwalt CL, Patkar AA, Mannelli P, Blazer DG. The high prevalence of substance use disorders among recent MDMA users compared with other drug users: Implications for intervention. Addict Behav. 2009 Apr 1; doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.029. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yacoubian GS., Jr Correlates of ecstasy use among students surveyed through the 1997 College Alcohol Study. J Drug Educ. 2003;33:61–69. doi: 10.2190/DVEE-3UML-2HDB-D4XV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen CF, Hsu SY. Symptoms of ecstasy dependence and correlation with psychopathology in Taiwanese adolescents. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:866–869. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181568625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]